Abstract

Suppressor transfer RNAs (sup-tRNAs) have the potential to rescue nonsense mutations in a disease-agnostic manner and are an alternative therapeutic approach for many rare and ultrarare disorders. Among all human pathogenic nonsense variants, approximately 20% arise from C-to-T transitions that convert the CGA arginine codon into a UGA stop codon. While recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) has been successfully used to deliver a UAG-targeting sup-tRNA gene in vivo, extending this approach to UGA-targeting sup-tRNA genes has posed unique challenges related to rAAV vector production. Here, we demonstrate that an engineered UGA-sup-tRNA gene, designed with transcriptional regulatory elements, can be efficiently packaged into rAAV for in vivo delivery. A single administration in mouse models of two distinct lysosomal storage disorders restores enzymatic activity to approximately 10% of normal levels. Comparative analysis reveals differential sup-tRNA expression and aminoacylation patterns across tissue types, which correlate with enhanced therapeutic effects. The applied rAAV-based agents and engineering strategies expand the potential therapeutic scope of sup-tRNA therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Nonsense mutations are point mutations that convert a sense codon into a premature termination codon (PTC) in the mRNA, causing two deleterious events during translation: nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) and cessation of full-length protein synthesis. Nonsense suppression1,2, also known as stop codon readthrough therapy, allows translation machineries to decode the PTC during protein synthesis as they normally decode sense codons, thereby overcoming its detrimental effects without changing the DNA or mRNA sequences. As nonsense mutations account for approximately 11% of human pathogenic mutations, nonsense suppression has the potential to treat a large population in a gene-agnostic and disease-agnostic manner. This is an attractive feature considering the challenges associated with developing bespoke gene therapies or mutation-specific gene editing therapies for individual rare and ultrarare diseases with a small population3,4.

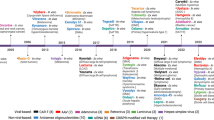

PTCs, like normal stop codons in mammalian cells, can be broadly categorized into three classes: UAA, UAG and UGA. By mutating the anticodon of a human lysine transfer RNA (tRNA) for decoding UAG, Kan and colleagues generated a suppressor tRNA (sup-tRNA) and demonstrated that it could readthrough a UAG PTC underlying β0 thalassemia, partially restoring the full-length β-globin protein in Xenopus oocyte5. Since then, a body of literature has documented the effectiveness of sup-tRNAs in overcoming various pathogenic nonsense mutations in cell culture models6. Recent breakthroughs in developing in vivo sup-tRNA therapy benefited from the nucleic acid delivery technologies that have advanced in the gene therapy field7,8. Albers and colleagues showed that lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) could deliver an in vitro transcribed UGA-targeting sup-tRNA (UGA-sup-tRNA) to the mouse liver and lung and mediated efficient readthrough of the PTC in a codelivered reporter mRNA9. We reported AAV-NoSTOP that uses recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) to deliver a UAG-sup-tRNA gene to a Hurler syndrome mouse model carrying a native nonsense mutation, which effectively and durably rescued the disease-associated PTC in multiple tissues following a single administration10. Pierce et al. used rAAV to deliver a prime editor engineered to convert an endogenous tRNA into a UAG-sup-tRNA, producing therapeutic benefit in the same Hurler syndrome mouse model11.

Among over 30,000 nonsense mutations documented in the Human Genetic Mutation Database12, point mutations that change the CGA arginine codon to UGA (Arg-to-UGA) are the most common type, representing nearly 20% (ref. 13). This is in part because of cytosine deamination, a spontaneous process that introduces a C-to-T transition in DNA. Arg-to-UGA is even more overrepresented when counting the number of individuals. For example, a study on 2,593 participants with Duchenne muscular dystrophy carrying 849 unique DMD nonsense mutations revealed that Arg-to-UGA accounted for 5% of nonsense mutations, whereas 30% of participants carried such mutations14. Therefore, suppressing UGA and installing arginine at the PTC holds great promise to benefit a large population.

In our previous study10, we developed a UAG-targeting AAV-NoSTOP gene therapy (AAV-NoSTOP(UAG)) as a proof of concept, as the Hurler syndrome mouse model carried a TAG nonsense mutation15. Developing AAV-NoSTOP(UGA) was met with several unique challenges, most notably the negative impact of constitutive UGA-sup-tRNA expression on rAAV production in HEK293 cells16. This effect was not observed with AAV-NoSTOP(UAG), likely because the UGA-sup-tRNA impacted certain mRNA(s) with a normal UGA stop codon essential for rAAV production. In this study, we used multiple molecular engineering approaches to improve UGA-sup-tRNA readthrough efficiency, rAAV packaging yield and vector genome homogeneity. We generated a mouse model carrying a genomic TGA nonsense mutation and demonstrated in vivo nonsense suppression and NMD inhibition. Comparative analysis revealed differential sup-tRNA levels and charging efficiencies across various tissues, which contributed to enhanced PTC readthrough in muscles. The broad therapeutic potential of the UGA-sup-tRNA was demonstrated with a second disease mouse model and in patient-derived fibroblasts, supporting its viability as a gene-agnostic and disease-agnostic therapeutic alternative.

Results

Evaluation of UGA-sup-tRNAArg candidates and expression cassette designs

A total of 21 human tRNAArg isodecoders are cataloged in the genomic tRNA database17, with four containing introns. Accordingly, we generated 25 sup-tRNAArg genes (R1–R25) with the anticodons mutated to 5′-UCA-3′ to decode the UGA stop codon, including four candidates with the intronic sequences removed (Supplementary Table 1). Using a dual-luciferase reporter assay, we compared the UGA readthrough abilities of the U6 promoter-driven sup-tRNAArg candidates through plasmid cotransfection in HEK293 cells (Extended Data Fig. 1a), which revealed R8 as the most efficient candidate (Extended Data Fig. 1b). As the U6 promoter and the internal tRNA promoter recruit different sets of transcription factors18, some of which are mutually exclusive19, we hypothesized that the U6 promoter may not necessarily boost sup-tRNA expression or they may interfere with each other. Therefore, we compared readthrough efficiency between U6-sup-tRNA and the sup-tRNA embedded in its natural flanking sequence (NFS-tRNA) (Extended Data Fig. 1c). We designed a tandem (2×) sup-tRNA cassette to enhance expression and function and generated a digenic PTC reporter carrying mutant genes encoding both a secretory protein (Gaussia luciferase, GLuc) and a cellular protein (enhanced green fluorescent protein with a FLAG tag at the C terminus, EGFP–FLAG) (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Both GLuc and EGFP measurements showed that placing R8 in either the human or the mouse NFS (hNFS-R8 and mNFS-R8, respectively) induced higher PTC readthrough than U6-R8 in HEK293 cells (Extended Data Fig. 1d–g).

To further compare sup-tRNA candidates in vivo, we delivered a pair of sup-tRNA and digenic PTC reporter plasmids to mouse liver through hydrodynamic injection (Fig. 1a,b). Consistent with the in vitro results, hNFS-R8 and mNFS-R8 restored higher GLuc activity in serum than U6-R8, which outperformed U6-R7 and U6-R17 (Fig. 1c). Quantification of the EGFP–FLAG protein in liver lysates by western blot more consistently showed the superior performance of h/mNFS-R8 over U6-R8 in promoting PTC readthrough (Fig. 1d), which was corroborated by immunohistochemistry analysis with liver tissue sections (Fig. 1e). Taken together, these results identified R8 in NFS as the leading candidate to readthrough UGA PTC and we chose to focus on 2×hNFS-R8 in the following studies.

a, Schematics showing the 2× sup-tRNA gene constructs with either a U6 promoter (U6-sup-tRNA) or NFS (NFS-sup-tRNA) and the digenic PTC reporter construct with a bidirectional promoter (BiP) driving the expression of mutant GLuc and EGFP–FLAG, both of which are disrupted with an in-frame TGA nonsense mutation. pA, polyadenylation signal. b, Workflow of the in vivo readthrough assay with WT mice. c, Bar graph showing the readthrough efficiency as quantified by measuring GLuc activity in the mouse serum. d, Bar graph (left) showing the readthrough efficiency as quantified by measuring EGFP–FLAG protein in the liver tissue lysate with western blot (right). In c,d, protein expression from the mice treated with a WT reporter plasmid (no TGA nonsense mutations) and an mCherry-only plasmid (no sup-tRNA) was defined as 100%. Each dot or lane represents an individual animal (n = 2 or 3). Data are presented as the mean and s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test. e, Representative images of anti-FLAG immunohistochemistry analysis of liver tissue sections from the mice treated with indicated plasmids. Scale bar, 200 µm. The schematic in b was created with BioRender.com.

Silencing UGA-sup-tRNA expression to improve rAAV production

We previously showed that standard triple transfection in HEK293 cells resulted in very low rAAV yield when packaging UGA-sup-tRNA genes because constitutive expression of UGA-sup-tRNA in HEK293 cells inhibited AAV replicase (Rep) and capsid (Cap) protein expression through unknown mechanisms16. This inhibitory effect was partially alleviated by low-cis triple transfection, which used 1–10% of the UGA-sup-tRNA plasmid (pCis) as in standard triple transfection16 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). When various R8 genes were subjected to rAAV packaging by low-cis triple transfection, we observed an inverse relationship between their readthrough efficiency and production yield, with the most potent 2×hNFS-R8 and 2×mNFS-R8 designs exhibiting only 5% of normal rAAV yield (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c).

Therefore, we sought to transcriptionally silence sup-tRNA expression during rAAV production. tRNA transcription requires the recognition of the internal box A and box B promoter elements by the transcription factor IIIC (TFIIIC)20,21. TFIIIB binds to TFIIIC and recruits the RNA polymerase III (Pol III) to initiate transcription22 (Fig. 2a). As the binding sites of TFIIIB and Pol III are within approximately 40 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS)23, we reasoned that placing an operator–repressor system near the TSS may serve as a molecular obstruction to prevent TFIIIB and/or Pol III recruitment, thereby attenuating tRNA expression (Fig. 2a). To this end, we initially inserted a tetracycline operator (TetO, 19 bp) either immediately or at 20 bp upstream of the sup-tRNA leader sequence (6 bp) and attempted to silence sup-tRNA by codelivering the Tet repressor (TetR)24 (Extended Data Fig. 3a). However, this approach did not dampen the readthrough function of sup-tRNA as measured using the digenic PTC reporter assay, suggesting that sup-tRNA expression was insufficiently inhibited (Extended Data Fig. 3b). By contrast, the Cym repressor (CymR)25 robustly inhibited sup-tRNA-mediated readthrough when the cumate operator (CuO, 28 bp) was inserted at various positions and orientations (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). We focused on the CuO1 design, and validated the inhibitory effect of CymR on the PTC readthrough function of a 2×CuO-hNFS-R8 cassette (Fig. 2b,c). As expected, the steady-state UGA-sup-tRNA level was reduced by more than 80% (Fig. 2d). Encouraged by these results, we attempted to package 2×CuO-hNFS-R8 in AAV9 along with an additional CymR plasmid (Fig. 2e). We compared this approach to the low-cis method and assessed their combinatorial effects. The combined use of CuO and CymR partially restored Cap and Rep expression with 100% or 10% pCis (Fig. 2f) and improved rAAV yield up to 10% of the normal level (Fig. 2g), comparable to the yields obtained with 1% pCis. Combining CuO–CymR with 1% pCis did not further enhance production (Fig. 2g), suggesting that, under the 1% pCis condition, vector genome availability may become the limiting factor. This aligns with our previous findings that 1% pCis resulted in lower rAAV production for permissive transgenes (for example, EGFP) compared to standard triple transfection16.

a, Cartoons showing that a sup-tRNA gene recruits transcription factors (only TFIIIB and TFIIIC are shown for simplicity) and Pol III to initiate transcription (top) and that the operator–repressor binding blocks this process presumably by steric hindrance (bottom). b, Schematics showing the plasmid constructs. c, Representative images of EGFP fluorescence in transfected HEK293 cells (left) and quantification of GLuc activity in culture medium (right) to measure readthrough efficiency following co-transfection of indicated plasmids. When the CymR plasmid was not included (−CymR), a plasmid expressing mCherry was used instead to keep the total amount of DNA in cotransfection the same. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as the mean and s.d. d, Bar graph showing the sup-tRNA levels expressed from the 2×hNFS-R8 construct or 2×CuO-hNFS-R8 construct in the absence or presence of the CymR plasmid in HEK293 cells. Data are presented as the percentage of sup-tRNA to the parental isodecoder and normalized to the −CymR condition. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as the mean and s.d. e, Cartoon showing the cotransfection step in rAAV production in the presence or absence of the CymR plasmid. f, Representative western blot images showing the Cap (top), Rep (middle) and GAPDH (bottom; serving as the loading control) protein expression in HEK293 cells undergoing rAAV9 production with indicated plasmid cotransfection. g, Bar graph showing the rAAV9 titers in the crude lysates of HEK293 cell cultures cotransfected with indicated plasmids. Data are normalized to the titer of rAAV9.mCherry produced with 100% pCis in parallel (defined as 100%) and presented as percentages. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 4). Data are presented as the mean and s.d. In c,d, statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided unpaired t-test.

Optimization of rAAV yield, purity, and vector genome homogeneity

We reasoned that UGA-sup-tRNA expression before sufficient CymR expression from plasmid may compromise rAAV production and that a HEK293 cell line constitutively expressing CymR may promptly silence UGA-sup-tRNA expression from pCis upon transfection. Therefore, we stably integrated the CymR gene into the AAVS1 locus of HEK293 cells through CRISPR-mediated gene editing (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b) and selected clonal cell lines that could both silence a CuO/CymR-controlled EGFP reporter and restore its expression with cumate, which is a small molecule that disrupts CuO–CymR binding25 (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). A subset of the clonal cell lines was subjected to an rAAV9 production assay packaging the 2×CuO-hNFS-R8 construct. Compared to unmodified HEK293 cells, four CymR cell lines (M3, M6, M13 and M20) showed marked increases in rAAV titer (Fig. 3a). When tested for large-scale production of rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8, the M20 cell line emerged as the most efficient (Extended Data Fig. 4e) and, therefore, was selected for the following studies.

a, Bar graph showing the rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8 titers in the crude lysates of HEK293 or various CymR monoclonal cell line cultures cotransfected with indicated plasmids. Data are normalized to the titer of rAAV9.mCherry produced with 100% pCis in parallel (defined as 100%) and presented as percentages. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 2). Data are presented as the mean. b, Tabulation of the vector genome abundance and CymR DNA encapsidation levels in purified rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8 vectors produced with the M20 cell line in the absence or presence of the CymR plasmid. GC, genome copies. c, Image of denaturing alkaline gel electrophoresis and DNA stain of the packaged DNA extracted from indicated vectors. The rAAV9.2×U6-UAG-sup-tRNA was produced using unmodified HEK293 cells as described previously10. The rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8 was produced using the M20 cell line in the absence or presence of the CymR plasmid as indicated. The black arrow indicates the full-length vector genome. The gray arrow indicates the shortened vector genome generated by recombination between repeating sup-tRNA cassettes. Two independent biological replicates were performed. d, Schematics showing four vector genome designs (VG1–VG4) carrying two CuO-NFS-R8 cassettes. The lengths of gene expression cassettes are labeled but not drawn to scale. ITR, inverted terminal repeat. e, Image of denaturing alkaline gel electrophoresis and DNA stain of the packaged DNA extracted from indicated vectors. The black arrow indicates the full-length vector genome. Gray arrows indicate the shortened vector genomes generated by recombination between repeating sup-tRNA cassettes. A single AAV preparation lot was used for each vector.

To demonstrate the broad utility of the CuO–CymR element to enable AAV packaging, we tested two additional UGA-sup-tRNAArg designs obtained by molecular engineering: tRT5 that harbors two base-pair changes in the TΨC stem9 and optACE-tRNAArgUGA that carries optimized flanking sequences and four base-pair modifications across the TΨC stem, acceptor stem and anticodon stem26. Both the digenic PTC reporter and dual-luciferase PTC reporter assays consistently showed that hNFS-R8 and hNFS-tRT5 largely had comparable readthrough efficiencies and optACE-tRNAArgUGA exhibited lower readthrough efficiency (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). While all designs failed to produce AAV9 vectors in unmodified HEK293 cells, packaging the CuO-sup-tRNA genes was rescued to approximately 40–70% of normal titer in M20 cells (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Additionally, we found that packaging a UAA-sup-tRNA gene into AAV9 with unmodified HEK293 cells was also severely compromised and the CymR cell lines alleviated the inhibitory effects and restored rAAV titers (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e).

Although adding the CymR plasmid further increased yield (Fig. 3a), it introduced two drawbacks. First, the CymR plasmid DNA sequence was encapsidated into rAAV albeit at a low level (Fig. 3b), consistent with other studies showing plasmid DNA as a source of raw material-related AAV vector impurities16,27. Second, we previously showed that multimeric U6-UAG-sup-tRNA cassette designs led to recombination between the repeating sequences, resulting in AAV vector genome heterogeneity10. This was also observed with the rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8 produced using M20; adding the CymR plasmid exacerbated the vector genome heterogeneity (Fig. 3c). Therefore, we chose to use the M20 cell line without the additional CymR plasmid and tested several vector genome configurations (VG1–VG4) to improve rAAV purity (Fig. 3d). This comparative analysis showed that VG4, which positioned two CuO-hNFS-R8 cassettes in opposing orientations and separated by the mCherry cassette, exhibited the best vector genome homogeneity, with no recombined forms detectable by denaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3e). To more comprehensively characterize vector genome composition, we conducted single-molecule, long-read DNA sequencing, which confirmed that recombination occurred between the two sup-tRNA cassettes (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). VG4 generated a near-homogeneous full-length vector genome and, therefore, was used in the following animal studies.

Efficacy assessment in a mouse model with a native nonsense mutation

To evaluate therapeutic efficacy in vivo, we generated an IduaW401X(TGA) mouse model using CRISPR-mediated gene editing (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Like the TAG nonsense mutation in the IduaW401X(TAG) mouse model10,15, the TGA nonsense mutation abrogated IDUA enzyme activity and triggered NMD of the IduaW401X(UGA) mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). We performed a mass spectrometry (MS)-based analysis and determined that the UGA-sup-tRNAArg (R8) predominantly installs an arginine residue upon PTC readthrough (91.7%) but also incorporates glutamine and aspartate at lower frequencies (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Previous studies showed that the anticodon is the primary identity determinant of eukaryotic tRNAArg for its recognition by arginyl-tRNA synthetase28. Therefore, the anticodon modification in UGA-sup-tRNAArg (R8) likely mildly compromised aminoacylation fidelity and resulted in its mischarging with glutamine and aspartate. According to the aminoacylation profile of UGA-sup-tRNAArg (R8), we further tested several IDUA variants with a missense mutation at codon W401 (W401R, W401Q and W401D), which showed that W401R moderately reduced enzyme activities as compared with the wild-type (WT) tryptophan residue (Extended Data Fig. 7e–i). Nonetheless, the IDUA(W401R) variant retained over 70% of WT activity, suggesting that the full-length IDUA protein restored with the UGA-sup-tRNAArg can be well detectable by the sensitive enzyme activity assay.

In homozygous IduaW401X(TGA) mice (IduaKI/KI hereafter), a single administration of rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) through the tail vein restored 1.4% of IDUA enzyme activity in the liver when assessed at 4 weeks after treatment, whereas the efficacy was much lower (≤0.5%) in the heart and skeletal muscles (Fig. 4a,b). When delivered using MyoAAV, a muscle-tropic AAV capsid29, the same treatment regimen restored 7% to 17% of WT IDUA activity levels in the heart and skeletal muscles (Fig. 4c). As expected, PTC readthrough antagonized NMD and markedly restored the IduaW401X(UGA) mRNA levels in IduaKI/KI mice (Fig. 4d). However, MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) treatment marginally restored IDUA enzyme activity and barely inhibited NMD in the liver (Fig. 4c,d), likely because of its lower gene delivery efficiency in the liver compared to AAV9 (ref. 29) (Fig. 4e). Another cohort of mice was evaluated at 20 weeks after treatment (Extended Data Fig. 8). IDUA enzyme activity restoration and NMD inhibition levels remained comparable to those obtained at 4 weeks, demonstrating the durability of the treatment.

a, Workflow of in vivo assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) or MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) in IduaKI/KI mice. b, Bar graph showing the IDUA enzymatic activities in the indicated tissues collected from untreated WT mice, untreated IduaKI/KI mice or IduaKI/KI mice treated with rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) and killed at 4 weeks after treatment. Data are normalized to the WT levels as 100%. c, Bar graph showing the IDUA enzymatic activities in the indicated tissues collected from untreated WT mice, untreated IduaKI/KI mice or IduaKI/KI mice treated with MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) and killed at 4 weeks after treatment. Data are normalized to the WT levels as 100%. d, Bar graph showing the ratios of mouse Idua mRNA to Tbp mRNA (mIdua/mTbp) in the indicated tissues collected from untreated WT mice, untreated IduaKI/KI mice or IduaKI/KI mice treated with MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4). In b–d, each dot represents an individual animal (n = 5 or 6). e, Bar graph showing the vector genome (vg) abundance across various tissues collected from IduaKI/KI mice treated with either rAAV9.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) (rAAV9) or MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) (MyoAAV). Each dot represents an individual animal (n = 3 or 4). In b–e, data are presented as the mean and s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided unpaired t-test in b,c or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test in d,e. The schematic in a was created with BioRender.com.

Tissue preference of sup-tRNA-mediated PTC readthrough

One surprising observation was the lack of a positive correlation between gene delivery efficiency and PTC readthrough across tissues following MyoAAV treatment. Specifically, while liver contained more vector genomes than heart and quadriceps (quads) (Fig. 4e), PTC readthrough was more prominent in the latter tissues (Fig. 4c). As endogenous tRNA expression exhibits tissue-specific differences30,31, we hypothesized that this discrepancy was because of differential sup-tRNA expression and/or function across different tissues. To test this hypothesis and also evaluate safety, we treated a group of normal mice with MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) and quantified steady-state sup-tRNA levels and charging efficiency across multiple tissues (Fig. 5a). We found that the sup-tRNA abundance was much higher in the heart and quads compared to liver when normalized to either the parental isodecoder (CCT-4) or all isodecoders with the CCU anticodon (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 2). The sup-tRNA was charged at lower levels than the parental isodecoder in all tissues (Fig. 5c), likely because the anticodon is a major identity element for the recognition by arginyl-tRNA synthetase32 and mutating the anticodon from CCU to UCA compromised aminoacylation. Nonetheless, the sup-tRNA was charged more efficiently in the heart and quads than in the liver (Fig. 5c).

a, Schematics showing the molecular workflow to quantify tRNA level and charging efficiency. The sup-tRNA with the UCA anticodon (blue) and the isodecoders with the CCU anticodon, including the sup-tRNA’s parental isodecoder, can be charged with an amino acid (gray circle) at the CCA at the 3′ terminus or uncharged. b, Bar graph showing the sup-tRNA levels normalized to either its parental isodecoder (left) or total CCT isodecoders (right) across three tissues as indicated. c, Bar graph showing the charging efficiencies of sup-tRNA (blue) and its parental isodecoder across various tissues. d, Bar graph showing the levels of sup-tRNA’s parental isodecoder relative to total CCT isodecoders across various tissues. In b–d, male normal mice at 5–6 weeks of age were treated with MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) (MyoAAV+) or left untreated (MyoAAV−) and killed 10 weeks later for tissue collection. Each dot represents an individual mouse (n = 3). Data are presented as the mean and s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test in b,c and two-sided t-test in d.

Together, we attributed the muscle-selective PTC readthrough to the high steady-state levels and charging efficiencies of the sup-tRNA. The parental isodecoder, CCT-4, also exhibited better charging efficiencies and higher steady-state levels in the heart and quads than in the liver (Fig. 5c,d), suggesting that it may be feasible to predict the performance of a sup-tRNA by the tissue preference of its parental isodecoder. Expressing the sup-tRNA had little to no impact on the charging efficiency or expression levels of its parental isodecoder (Fig. 5c,d). We observed no signs of toxicity in histological analyses of various tissues, including the heart and quads that exhibited high PTC readthrough (Extended Data Fig. 9a). The safety profile was further supported by body weight gain and normal clinical blood chemistry (Extended Data Fig. 9b and Supplementary Table 3).

Efficacy assessment in a second mouse model and in patient-derived fibroblasts

To demonstrate the gene-agnostic and disease-agnostic feature of AAV-NoSTOP(UGA), we took advantage of an engineered mouse model of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2), which carries a TGA nonsense mutation. CLN2 is caused by biallelic loss-of-function mutations in the TPP1 gene encoding tripeptidyl peptidase 1. A mouse model of CLN2 was previously generated by knocking in the R207X(TGA) nonsense mutation in Tpp1 (Cln2KI/KI mouse hereafter)33. This mutation is orthologous to the human CLN2R208X(TGA) mutation, which is the most common nonsense mutation in persons with CLN2 disease and occurs with an allele frequency of 22% (ref. 33). Treatment with MyoAAV.2×CuO-hNFS-R8(VG4) in Cln2KI/KI mice for 4 weeks restored 7–12% of TPP1 enzyme activity in the heart and skeletal muscles through synergistic PTC readthrough and NMD inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 10a–c). Additionally, we obtained primary fibroblasts derived from a person with CLN2 carrying compound heterozygous Arg-to-TGA nonsense mutations (R127X/R208X). As rAAV-mediated transduction of in vitro cell culture is inefficient as compared to in vivo applications, we used lentiviral vectors to deliver the CuO-hNFS-R8 construct to the patient-derived fibroblasts, which restored TPP1 enzyme activity to 11% of the normal level (Extended Data Fig. 10d,e). Together, these data support the gene-agnostic and disease-agnostic feature of sup-tRNA therapy.

Discussion

Here, we report the development of AAV-NoSTOP(UGA) that installs arginine at a pathogenic UGA PTC during translation and, therefore, can potentially target approximately 20% of human pathogenic nonsense mutations and restore the WT protein synthesis. It builds on multiple optimization steps to improve PTC readthrough efficiency, rAAV production yield and vector genome homogeneity. These efforts led us to demonstrate efficacy in two disease mouse models, underscoring the gene-agnostic and disease-agnostic feature of sup-tRNA therapy. Using a mouse model with a nonsense mutation in a native, nuclear gene is a rigorous experimental approach to evaluate in vivo sup-tRNA therapy. First, it reflects protein restoration from a nonsense allele in the context of NMD, which can greatly degrade PTC-containing mRNA and limit protein synthesis34,35,36. This sets our study apart from previous work involving the codelivery of an exogenous, NMD-resistant readthrough substrate and a UGA-sup-tRNA in WT mice9,37. Second, it accounts for the delivery barriers that remain a central challenge in the development of in vivo nucleic acid therapies. Third, it enables the assessment of potential toxic effects and disruptions to normal physiology at the organism level.

The PTC readthrough function of sup-tRNAs may be further enhanced by engineering the body sequence9,11,38 or flanking sequence26. However, packaging more potent UGA-sup-tRNA and UAA-sup-tRNA genes into AAV vectors may pose additional challenges. The transcriptional silencing approach described in this study may be further optimized to accommodate more demanding sup-tRNAs. For example, increasing the CymR expression level in the stable cell line and/or including multiple copies of CuO in the sup-tRNA cassette may more effectively silence expression. Alternatively, other programmable DNA-targeting molecular obstructions may be used, such as the deactivated Cas9 as in CRISPR interference for Pol II promoters39. Outside of nonsense sup-tRNAs, recent studies have demonstrated potential therapeutic applications of missense sup-tRNAs that decode a sense codon as another40,41. It is plausible that such missense sup-tRNAs may also compromise rAAV production by reducing yield and/or AAV Cap fidelity. In this scenario, transcriptional silencing may be a viable strategy to enable rAAV packaging for in vivo delivery. Moreover, combining the CuO-sup-tRNA gene design with a tissue-specific CymR expression cassette may enable tissue-specific silencing of sup-tRNA expression, thereby enhancing the safety profile.

Using prime editing to convert an endogenous tRNA gene into a sup-tRNA, known as PERT11, circumvents rAAV packaging limitations and can provide long-term efficacy when targeting dividing cells, because the sup-tRNA gene is genomically installed. In contrast, although rAAV-mediated transgene expression is stable in nondividing cells, the episomal vector DNA is diluted or lost during cell division. rAAV re-dosing is currently constrained by immune responses elicited by the initial administration, although continued research42,43 may ultimately enable repeated dosing if needed. Another potential advantage of PERT is that a single, genomically installed copy of the sup-tRNA gene may yield a more homogeneous expression profile across edited cells compared to episomal rAAV delivery, where uneven vector distribution can generate highly transduced subpopulations that may experience toxicity. Although both PERT and AAV-NoSTOP have shown tolerable safety profiles in mice under certain experimental conditions10,11, safety will need to be carefully evaluated in future translational studies.

One challenge of PERT is the efficient and accurate editing of endogenous tRNA loci because of their high sequence similarity, low tolerance for unintended edits and overall refractoriness to prime editing11. Another current constraint of PERT is that only a few natural tRNA isoacceptors in their endogenous genomic context can be converted into functional sup-tRNAs (tRNAArg, tRNASer, tRNALeu and tRNATyr for UAG; tRNAArg and tRNALeu for UGA; none for UAA)11. This limitation restricts the ability to restore the WT amino acid during readthrough. In contrast, ectopic expression of sup-tRNAs from all tested isoacceptor families supports robust readthrough activity for all three stop codons37. This discrepancy suggests that single-copy expression of a sup-tRNA from its endogenous genomic locus may limit potency. Factors such as CpG density within the local genomic context44 and Pol III terminator configuration11 can dampen tRNA expression level or impose tissue specificity45. rAAV-based episomal delivery bypasses these constraints by allowing flexible cassette design, controlled tissue tropism and tunable delivery efficiency, leading to higher sup-tRNA expression and activity. In addition to its potential as a therapeutic approach, PERT provides a stringent platform for identifying and engineering sup-tRNAs that function effectively at a single-copy level; these optimized variants can subsequently be delivered by rAAV or LNP to achieve even greater potency. Together, these complementary approaches may ultimately enable the development of more effective sup-tRNA therapies.

Off-target, transcriptome-wide readthrough at normal termination codons (NTCs) is a major safety concern for sup-tRNA therapy. However, a substantial body of literature over the past few decades has documented that readthrough at NTCs is less likely to occur than at PTCs46. Factors contributing to the strong termination signal of NTCs include their surrounding sequence context47,48 and the proximity to the poly(A) tail (thus, poly(A)-binding proteins)49. Consistent with this notion, ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) studies showed that sup-tRNAs generally induced undetectable or low levels of NTC readthrough10,37. It should be noted that Ribo-seq quantifies ribosome-protected mRNA fragments mapped to 3′ untranslated regions and, therefore, interrogates readthrough events at the mRNA level. However, at the protein level, several studies have shown that C-terminally extended peptides, generated by NTC readthrough, are recognized by cellular surveillance mechanisms and subsequently degraded, which ensures the high fidelity of proteome50,51,52,53,54. Thus, while Ribo-seq provides an exhaustive measurement of global NTC readthrough, the proteomic changes induced by sup-tRNA are likely limited and tolerable to some extent. Consistent with this hypothesis, we showed that AAV-NoSTOP treatment in mice remains safe, despite the detection of NTC readthrough using Ribo-seq10. Future studies may involve high-sensitivity proteomics analysis to investigate the consequences of global NTC readthrough at the protein level.

The small populations of individual rare and ultrarare genetic diseases present unique challenges for gene therapy development, including difficulties in conducting clinical trials and a lack of commercial viability3,4. Sup-tRNA can potentially target multiple unaddressed indications with a common mutation, such as a TGA nonsense mutation, and enable a one-size-fits-many gene therapy paradigm55. Future clinical studies may involve recruiting participants with the same PTC across multiple diseases and adopt a basket trial design, similar to those used in oncology56,57, to streamline translation. Thus, sup-tRNA could become a viable gene therapy solution for a larger population sharing a common PTC. In particular, the UGA-sup-tRNA gene-engineering approaches described in this study greatly broaden the therapeutic potential of sup-tRNA by enabling AAV delivery and targeting the most common type of pathogenic nonsense mutation. Furthermore, our analysis on sup-tRNA levels and charging efficiencies across various tissues reinforces the notion that tRNA biogenesis and function can be tissue-dependent30,31. It may be feasible to develop AAV-NoSTOP therapeutics that exhibit tissue-selective targeting or detargeting. Although clinical deployment may require tailored agents for different tissues, the potential benefits of greater specificity and improved safety could outweigh the limitations in generalizability.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, 11965-084) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Gibco, 26140-079) and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin antibiotics (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Patient-derived fibroblasts were purchased from the Coriell Institute and were maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), 30-2003) supplemented with 15% (v/v) FBS (Gibco, 26140-079) and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin antibiotics (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Transfection of the fibroblasts derived from an IDUA−/− participant (Coriell Institute, GM00798) was performed using TransfeX (ATCC, ACS-4005). CLN2 patient-derived fibroblasts (Coriell Institutes, GM16485) were infected with lentiviral vectors at a multiplicity of infection of 300 in the presence of 8 µg ml−1 polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, TR-1003-G). G418 (Life Technologies, 10131-027) was added to culture medium to a final concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1 at 24 h before cell collection. Fibroblasts derived from an IDUA+/− individual (Coriell Institute, GM00799) were used as normal control.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay to measure PTC readthrough in HEK293 cells

The dual-luciferase reporter expresses the Cypridina luciferase (CLuc) and GLuc, which are separated by the T2A sequence and the Mecp2R168X sequence context. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 150 ng per well of reporter plasmid and 1.2 ng per well of sup-tRNA plasmid in a 24-well plate using polyethylenimine (Polysciences, 23966-1). Cell culture medium was collected 24 h after transfection. CLuc was measured with a Pierce CLuc glow assay kit (Thermo Scientific, 16171) and GLuc was measured with a Pierce GLuc flash assay kit (Thermo Scientific, 16159) using a plate reader (BioTek) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The readthrough efficiency was defined as the GLuc/CLuc ratio from the Mecp2R168X construct normalized to the ratio observed for the WT construct (Mecp2).

Digenic reporter assay to measure PTC readthrough in HEK293 cells

The digenic reporter expresses GLuc-R44X and EGFP-Y39X under a bidirectional promoter58,59. The reporter plasmid with WT GLuc and EGFP serves as WT control. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 500 ng per well of the reporter plasmid, 500 ng per well of the CymR plasmid or an mCherry plasmid as control and 5 ng per well of the sup-tRNA plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000015) in a 12-well plate. GLuc in cell culture medium was measured 48 h after transfection and normalized to GLuc expressed from the WT reporter to calculate the readthrough efficiency. EGFP fluorescence in HEK293 cells was imaged using a Leica inverted fluorescence microscope. EGFP fluorescence intensity was quantified by ImageJ.

Animal use and treatment

The IduaKI/KI mouse model on the C57BL/6J background was generated using CRISPR-mediated gene editing. Cln2R207X mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (JAX, 030696) and bred in-house. To study sup-tRNA levels, charging efficiency and treatment safety, heterozygous Cln2R207 mice were used and killed at 10 weeks after treatment. For hydrodynamic injection, WT mice were intravenously injected with 2.5 ml of saline containing 25 µg of reporter plasmid and 25 µg of sup-tRNA plasmid. The mice were killed at 24 h after injection. rAAV vectors were intravenously administered at the dose of 3.5 × 1012 vector genomes per mouse and killed at 4 or 20 weeks after treatment as indicated to assess therapeutic efficacy in homozygous IduaKI/KI and Cln2R207/R207X mice. Mice were perfused with ice-cold PBS and tissues were immediately dissected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. All mice were housed at 22 ± 2 °C with 40% humidity and a 12 h light–dark cycle. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School (PROTO202100011 and PROTO202100013) and performed in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations.

Western blotting

Cell cultures were lysed in ice-cold M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78501) with protease inhibitor (Roche, 4693159001). Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold T-PER protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78510) with protease inhibitor (Roche, 4693159001) using TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Total protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, 23225). Normalized protein lysate was boiled with 4× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610747) at 95 °C for 5 min. The primary antibodies mouse anti-Flag M2 (Sigma, F1804; 1:5,000 dilution), rabbit anti-mCherry (Novus biologicals, NBP2-25157; 1:3,000 dilution), rabbit anti-GAPDH (Abcam, ab9485; 1:5,000 dilution), mouse anti-AAV VP1/VP2/VP3 (PROGEN, 690058; 1:500 dilution) and mouse anti-AAV2 Rep (PROGEN, 61069; 1:200 dilution) and the secondary antibodies LI-COR IRDye 680RD goat anti-rat IgG (H + L) (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-68076; 1:10,000 dilution), LI-COR IRDye 680RD goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-68070; 1:10,000 dilution), LI-COR IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-32211; 1:10,000 dilution) and LI-COR IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-32210; 1:10,000 dilution) were used in western blotting. Blot membranes were scanned with a LI-COR scanner (Odyssey). Western blot quantification analysis was performed with Image Studio Lite (LI-COR).

Plasmids

All sup-tRNA and reporter constructs were cloned into rAAV single-stranded transfer plasmid using NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly master mix (New England BioLabs, E2621) and verified by whole-plasmid sequencing. The sequences of sup-tRNA and reporter expression cassettes are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

AAV vector production using adherent HEK293 cells

A small-scale AAV vector production assay was performed by standard triple transfection of HEK293 cells in 24-well plates. Each well was transfected with 0.25 µg each of three plasmids carrying the vector genome (pCis), Rep/Cap (pTrans, pRep2/Cap9; Addgene, 112865) and adenovirus helper genes (pHelper; Addgene, 112867) using the calcium phosphate method (Promega, E1200). In low-cis triple transfection, the pCis plasmid was reduced to 10% or 1% by mass. In the quadruple transfection with the additional CymR plasmid (pCymR), 0.2 µg of pCymR was cotransfected. The culture medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin without FBS at 24 h after transfection. Cells and culture media were harvested at 72 h after transfection and subjected to three consecutive freeze–thaw cycles. The crude lysates were centrifuged at 14,000g per min for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. Cleared crude lysates were treated with DNase-I for 1 h at 37 °C and proteinase K followed by tittering by droplet digital (ddPCR).

Midiscale AAV vectors packaging various genome designs (VG1–VG4) were produced in three 15-cm dishes for each vector. Then, 15 µg each of pCis, pRep/Cap and pHelper plasmids were cotransfected to cells cultured in one 15-cm dish using polyethylenimine. After 24 h, cell culture medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin without FBS. Then, 72 h after transfection, cells and culture media were harvested. rAAV vectors were purified with AAVpro Purification Kit (Takara, 6675) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

In large-scale AAV vector production, the calcium phosphate method was used to cotransfect 1.5 mg each of pCis, pRep/Cap and pHelper plasmids to approximately 1 × 109 cells cultured in ten roller bottles. When the additional pCymR was used, 1.2 mg of pCymR was cotransfected. Then, 72 h after transfection, AAV vectors were purified through two rounds of cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation. Titers of purified AAV vectors were quantified by ddPCR.

AAV vector DNA analysis by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis and nanopore sequencing

AAV vector DNA was extracted from purified rAAV using QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, 51104) following the manufacturer’s protocol for viral DNA isolation. Briefly, 0.8% agarose (w/v) gel was made with ultrapure water and 0.1 volumes of 10× alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis buffer (500 mM NaOH and 10 mM EDTA) was added when cooled to 55 °C. Purified vector DNA was mixed with 6× alkaline gel loading buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, AAJ62157AB) and 10× alkaline agarose buffer and loaded to alkaline gel. Electrophoresis was performed at a voltage of 3 V cm−1 on ice for approximately 3 h. Then, the gel was soaked in neutralization solution (BioWorld, 10750014) for 45 min at room temperature. The neutralized gel was stained with SYBR gold (1:10,000 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific, S11494) in 1× TAE buffer for 15 min and imaged using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ Imaging System. Nanopore sequencing of the AAV vector DNA was conducted by Plasmidsaurus and analyzed using Geneious Prime.

Generation of CymR stable cell lines

Adherent HEK293 cells were transfected with a mixture of a Cas9-expressing plasmid, an AAVS1-targeting sgRNA plasmid (courtesy of A. Brown; target sequence: CTGTCCCTAGTGGCCCCACTG) and the donor plasmid pAAVS1 LHA-SA-P2A-CymR-T2A-PuroR-bGH (pHL379) at a mass ratio of 1:1:3. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Scientific, 11668027). Then, 3 days after transfection, the cells were split and selected with puromycin (1 µg ml−1) for 7 days. Monoclonal cell lines were isolated through serial dilution, expanded and subjected to a CymR function assay to identify candidate clones.

IDUA enzyme activity assay

Patient-derived fibroblasts were lysed in ice-cold M-PER protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78501) with protease inhibitor (Roche, 11873580001). Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold T-PER protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78510) with protease inhibitor (Roche, 4693159001) using TissueLyser II (Qiagen). The lysates were centrifuged at 14,000g per min for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected for total protein quantification using the BCA assay (Pierce, 23225). Fibroblast lysates containing around 6 µg of total protein or tissue lysates containing 60 µg of total protein were used in the enzymatic reaction (100 µl of total reaction volume), which included sodium formate buffer pH 3.5 (130 mM), d-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone monohydrate (0.42 mg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich, S0375) and 4MU-iduronic acid (0.12 mM; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-220961). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 20 h and quenched with glycine buffer, pH 10.8. The fluorescence of released 4MU (excitation wavelength: 365 nm; emission wavelength: 450 nm) was detected using a plate reader (BioTek) and compared against a standard curve generated using 4MU (Sigma-Aldrich, M1381). The relative IDUA activity was normalized to the IDUA activity detected with WT samples.

TPP1 enzyme activity assay

Total protein of cell or tissue lysates were determined using the BCA assay (Pierce, 23225) and normalized to the same total protein concentration. Then, 10 µl of each lysate was incubated with 20 µl of activation buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 50 mM formic acid/sodium formate, pH 3.5) at 37 °C for 30 min. After activation, 20 µl of reaction solution containing 500 µM of Ala-Ala-Phe 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin substrate (Sigma, A34010) in substrate buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0) was added. Fluorescence from the released 4MU was continuously monitored at 37 °C every 10 min for 2 h using a plate reader (BioTek) set to kinetic mode (excitation: 365 nm; emission: 450 nm). TPP1 activity was measured within the linear range and compared against a standard curve generated using 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Sigma, A9891).

ddPCR

RNA and DNA were extracted from mouse liver or heart using an AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, 80204). Muscle RNA and DNA were isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen, 15596018) and QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, 51304), respectively. Isolated RNA was reverse transcribed using a high-capacity complementary DNA (cDNA) reverse transcription kit (Fisher Scientific, 43-688-13). Mouse Idua or Tpp1 cDNA was quantified in a multiplexed ddPCR reaction using Taqman reagents targeting Idua (Thermo Fisher Scientific, assay ID: Mm01198845_m1) or Tpp1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, assay ID: Mm00487016_m1), respectively, and mTbp (Thermo Fisher Scientific, assay ID: Mm01277042_m1). The titers of AAV vectors were quantified using a customized Taqman reagent targeting mCherry (forward primer: CAGAGGCTGAAGCTGAAGGA; reverse primer: GCTTCTTGGCCTTGTAGGTG; probe: CGGCGGCCACTACGACGCTG). CymR sequence was quantified using a customized Taqman reagent (forward primer: CTGGCAACATTTGAGTGGCT; reverse primer: AAGAATTCGGCTGCATCGTC; probe: AGCGAGCCGGGCTCTGCTCC). AAV vector genome copy number in mouse tissues was quantified using Taqman reagent targeting mCherry and Tfrc (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4458367). ddPCR was performed with a QX200 instrument (Bio-Rad) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Lentiviral vectors

hNFS-CuO-R8 and EGFP driven by the CMV promoter were cloned into the lentiviral transfer plasmid pLenti-CSCGW2. Lentiviral vectors were packaged using the third-generation system. The transfer plasmid was cotransfected with packaging plasmids (pMDLg/Prre and pRSV/REV) and the envelope plasmid (pHCMV/VSVG) into HEK293T cells using the calcium phosphate method. Medium was collected at 48 h and 72 h after transfection and ultracentrifuged to concentrate virus. The virus titer was determined using a QuickTiter lentivirus titer kit (Cell Biolabs, VPK-107).

Sup-tRNA quantification and measurement of tRNA charging efficiency

Total RNA from tissues was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, 15596018) and resuspended in acetate buffer (10 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5 and 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0). RNA was subjected to periodate oxidation in freshly prepared 50 mM NaIO4 and β-elimination in 60 mM sodium borate as previously described60. Mature tRNAs were isolated by denaturing 8% TBE–urea PAGE and recovered by crush-and-soak method. For sup-tRNA quantification in HEK293 cells, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, 15596018) and dissolved in RNase-free water, followed by deacylation in 75 mM Tri-HCl (pH 9.0) as previously described61. Small RNA (17–200 nt) including mature tRNA was isolated using Zymo RNA clean and concentrator kit (R1017). tRNAs were demethylated with the rtStar tRF&tiRNA pretreatment kit (Arraystar, AS-FS-005) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by end repair using T4 PNK (New England Biolabs, M0201S) and ligated with 3′ adaptor (5′-pGATTCTAGCAAGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAA/ddC/-3′) using T4 RNA ligase 2, truncated KQ (New England Biolabs, M0373L). tRNA was cleaned up using Zymo RNA clean and concentrator kit (Zymo Research, R1015) before being processed to the next reaction. Adaptor-ligated tRNAs were isolated by denaturing 8% TBE–urea PAGE and recovered by crush-and-soak method. Adaptor-ligated tRNAs were incubated with SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, 18090200) at 55 °C for 18 h with the primer JW845 (5′-TTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGCTAGAATC-3′). KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche, 7958935001) was used to amplify tRNA cDNA using primers MX250 (5′-CTTCTTCAAGGACGACGGCAACTACAAGACCCGCGCCGAGGTGAAGTTCGGCCCCAGTGGCCTAATGGATAAG-3′) and JM857 (5′-CCTTGAAGTCGATGCCCTTCAGCTCGATGCGGTTCACCAGGGTGTCGCCCTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGCTAGAATC-3′). Amplicons were purified with Zymo gel DNA recovery kit (Zymo Research, D4001) and subjected to nanopore sequencing at Plasmidsaurus. Sequencing reads were analyzed using Geneious Prime.

Immunoprecipitation and MS

The plasmids expressing 2×hNFS-R8 and mIdua cDNA (WT or W401X) fused with a FLAG tag on the C terminus were cotransfected in HEK293 cells. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitor (Roche, 4693159001). mIDUA–FLAG protein was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (Sigma-Aldrich, A2220-5ML) at 4 °C overnight, eluted with 4× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610747) at 95 °C for 10 min and subjected to SDS–PAGE. Gels were stained with Simplyblue SafeStain (Invitrogen, LC6060) to visualize the mIDUA–FLAG bands, which were excised and processed for MS.

MS and analyses were conducted at The MS Facility at UMass Chan Medical School. The gel samples were digested overnight at 37 °C using trypsin (Promega), eluted with 100 µl of 50% acetonitrile in water and then dried in a SpeedVac. The peptides were reconstituted in 20 µl of 0.1% formic acid in 5% acetonitrile, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 rcf for 16 min. Subsequently, 18 µl of the sample was transferred to nonbinding high-performance liquid chromatography (LC) vials. Next, 4 µl of the reconstituted samples was then injected into the MS instrument, a TimsTOF Pro2 (Bruker), coupled with a nanoElute LC system (Bruker). The analysis was carried out on an in-house packed C18 column (250 mm × 75 µm inner diameter, 3 µm, 120-Å pore size) using a 30-min gradient at a flow rate of 500 nl min−1 with a solvent composition of solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The data acquisition was processed in data-dependent analysis using the parallel accumulation–serial fragmentation (PASEF) method. The method consists of 10 MS/MS PASEF scans per topN acquisition cycle, with ramp and accumulation times of 100 ms, covering an m/z range from 100 to 1,700 and an ion mobility range (1/K0) from 0.70 to 1.30 V s cm−2. Collision energy settings followed a linear function of ion mobility, ranging from 20 eV at 0.6 V s cm−2 to 59 eV at 1.6 V s cm−2, using default parameters. Calibration of the instrument was performed using three ions from the ESI-L Tuning Mix (Agilent) (m/z 622, 922 and 1,222).

The raw data were processed using the Fragpipe/MSFragger specific (trypsin) workflow against a database containing all possible amino acid incorporations at position 401. Results were visualized and statistically analyzed using Scaffold version 5.3.3 9 (Proteome Software) and relative quantification of the most probable amino acid incorporation was estimated using Skyline (64-bit) version 24.1.0.414 (5b5ea5889c).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Mouse tissues were fixed in 10% formalin buffer (Fisher Scientific, SF100-20) overnight and embedded in paraffin. Sectioning, hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry were performed at the Morphology Core at the UMass Chan Medical School under standard conditions. Mouse anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma, F1804; 1:500 dilution) was used in immunohistochemistry. Images were acquired on a Leica DM5500 B microscope.

Clinical serum biochemistry

Mouse blood was collected in a BD SST microtainer (BD Pharmingen, 365967) and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min to separate the serum. Serum biochemical analysis was conducted at IDEXX BioAnalytics for the rodent expanded tox panel (60514). The values of normal ranges are from previous studies62,63.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 10. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using a two-sided t-test. Comparisons among three or more groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a pairwise comparison corrected for multiple comparisons.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. Long-read sequencing data of AAV genomes and tRNA amplicons were deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under BioProject PRJNA1265762. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Keeling, K. M., Xue, X., Gunn, G. & Bedwell, D. M. Therapeutics based on stop codon readthrough. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 15, 371–394 (2014).

Morais, P., Adachi, H. & Yu, Y. T. Suppression of nonsense mutations by new emerging technologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4394 (2020).

Zanello, G. et al. Targeting shared molecular etiologies to accelerate drug development for rare diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 15, e17159 (2023).

Yingling, N., Sena-Esteves, M. & Gray-Edwards, H. L. A paradox of the field’s own success: unintended challenges in bringing cutting-edge science from the bench to the market. Hum. Gene Ther. 35, 83–88 (2024).

Temple, G. F., Dozy, A. M., Roy, K. L. & Kan, Y. W. Construction of a functional human suppressor tRNA gene: an approach to gene therapy for β-thalassaemia. Nature 296, 537–540 (1982).

Coller, J. & Ignatova, Z. tRNA therapeutics for genetic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 23, 108–125 (2024).

Wang, D., Stevens, G. & Flotte, T. R. Gene therapy then and now: a look back at changes in the field over the past 25 years. Mol. Ther. 33, 1889–1902 (2025).

Ward, C. et al. Mechanisms and delivery of tRNA therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 124, 7976–8008 (2024).

Albers, S. et al. Engineered tRNAs suppress nonsense mutations in cells and in vivo. Nature 618, 842–848 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. AAV-delivered suppressor tRNA overcomes a nonsense mutation in mice. Nature 604, 343–348 (2022).

Pierce, S. E. et al. Prime editing-installed suppressor tRNAs for disease-agnostic genome editing. Nature 648, 191–202 (2025).

Stenson, P. D. et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD((R))): optimizing its use in a clinical diagnostic or research setting. Hum. Genet. 139, 1197–1207 (2020).

Wang, J., Gao, G. & Wang, D. Developing AAV-delivered nonsense suppressor tRNAs for neurological disorders. Neurotherapeutics 21, e00391 (2024).

Torella, A. et al. The position of nonsense mutations can predict the phenotype severity: a survey on the DMD gene. PLoS ONE 15, e0237803 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Characterization of an MPS I-H knock-in mouse that carries a nonsense mutation analogous to the human IDUA-W402X mutation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 99, 62–71 (2010).

Liu, H. et al. Producing high-quantity and high-quality recombinant adeno-associated virus by low-cis triple transfection. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 32, 101230 (2024).

Chan, P. P. & Lowe, T. M. GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D184–D189 (2016).

White, R. J. Transcription by RNA polymerase III: more complex than we thought. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 459–463 (2011).

Moqtaderi, Z. et al. Genomic binding profiles of functionally distinct RNA polymerase III transcription complexes in human cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 635–640 (2010).

Galli, G., Hofstetter, H. & Birnstiel, M. L. Two conserved sequence blocks within eukaryotic tRNA genes are major promoter elements. Nature 294, 626–631 (1981).

Hofstetter, H., Kressman, A. & Birnstiel, M. L. A split promoter for a eucaryotic tRNA gene. Cell 24, 573–585 (1981).

Ramsay, E. P. & Vannini, A. Structural rearrangements of the RNA polymerase III machinery during tRNA transcription initiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1861, 285–294 (2018).

Kassavetis, G. A. et al. The role of the TATA-binding protein in the assembly and function of the multisubunit yeast RNA polymerase III transcription factor, TFIIIB. Cell 71, 1055–1064 (1992).

Gatz, C. & Quail, P. H. Tn10-encoded tet repressor can regulate an operator-containing plant promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 1394–1397 (1988).

Mullick, A. et al. The cumate gene-switch: a system for regulated expression in mammalian cells. BMC Biotechnol. 6, 43 (2006).

Porter, J. J., Ko, W., Sorensen, E. G. & Lueck, J. D. Optimization of ACE-tRNAs function in translation for suppression of nonsense mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, 14112–14132 (2024).

Wright, J. F. Product-related impurities in clinical-grade recombinant AAV vectors: characterization and risk assessment. Biomedicines 2, 80–97 (2014).

McShane, A., Hok, E., Tomberlin, J., Eriani, G. & Geslain, R. The enzymatic paradox of yeast arginyl-tRNA synthetase: exclusive arginine transfer controlled by a flexible mechanism of tRNA recognition. PLoS ONE 11, e0148460 (2016).

Tabebordbar, M. et al. Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Cell 184, 4919–4938 (2021).

Dittmar, K. A., Goodenbour, J. M. & Pan, T. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 2, e221 (2006).

Huang, J. et al. Tissue-specific reprogramming of host tRNA transcriptome by the microbiome. Genome Res. 31, 947–957 (2021).

Giege, R. & Eriani, G. The tRNA identity landscape for aminoacylation and beyond. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 1528–1570 (2023).

Geraets, R. D. et al. A tailored mouse model of CLN2 disease: A nonsense mutant for testing personalized therapies. PLoS ONE 12, e0176526 (2017).

Keeling, K. M. et al. Attenuation of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay enhances in vivo nonsense suppression. PLoS ONE 8, e60478 (2013).

Amar-Schwartz, A. et al. Inhibition of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay may improve stop codon read-through therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 2455–2463 (2023).

Linde, L. et al. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay affects nonsense transcript levels and governs response of cystic fibrosis patients to gentamicin. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 683–692 (2007).

Lueck, J. D. et al. Engineered transfer RNAs for suppression of premature termination codons. Nat. Commun. 10, 822 (2019).

Jewel, D. et al. Virus-assisted directed evolution of enhanced suppressor tRNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 20, 95–103 (2023).

Gilbert, L. A. et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451 (2013).

Hou, Y. et al. Engineered mischarged transfer RNAs for correcting pathogenic missense mutations. Mol. Ther. 32, 352–371 (2024).

Tennakoon, R. et al. Glutamine missense suppressor transfer RNAs inhibit polyglutamine aggregation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 36, 102442 (2025).

Leborgne, C. et al. IgG-cleaving endopeptidase enables in vivo gene therapy in the presence of anti-AAV neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 26, 1096–1101 (2020).

Loeb, E. J. et al. Complete neutralizing antibody evasion by serodivergent non-mammalian AAVs enables gene therapy redosing. Cell Rep. Med. 6, 102475 (2025).

Thornlow, B. P. et al. Predicting transfer RNA gene activity from sequence and genome context. Genome Res. 30, 85–94 (2020).

Ishimura, R. et al. Ribosome stalling induced by mutation of a CNS-specific tRNA causes neurodegeneration. Science 345, 455–459 (2014).

Beryozkin, A., Nagel-Wolfum, K., Banin, E. & Sharon, D. Factors affecting readthrough of natural versus premature termination codons. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1415, 149–155 (2023).

Wangen, J. R. & Green, R. Stop codon context influences genome-wide stimulation of termination codon readthrough by aminoglycosides. eLife 9, e52611 (2020).

Mangkalaphiban, K. et al. Extended stop codon context predicts nonsense codon readthrough efficiency in human cells. Nat. Commun. 15, 2486 (2024).

Amrani, N. et al. A faux 3’-UTR promotes aberrant termination and triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature 432, 112–118 (2004).

Kramarski, L. & Arbely, E. Translational read-through promotes aggregation and shapes stop codon identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 3747–3760 (2020).

Hashimoto, S., Nobuta, R., Izawa, T. & Inada, T. Translation arrest as a protein quality control system for aberrant translation of the 3’-UTR in mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 593, 777–787 (2019).

Arribere, J. A. et al. Translation readthrough mitigation. Nature 534, 719–723 (2016).

Shibata, N. et al. Degradation of stop codon read-through mutant proteins via the ubiquitin-proteasome system causes hereditary disorders. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 28428–28437 (2015).

Muller, M. B. D., Kasturi, P., Jayaraj, G. G. & Hartl, F. U. Mechanisms of readthrough mitigation reveal principles of GCN1-mediated translational quality control. Cell 186, 3227–3244 (2023).

Anastassiadis, T. & Kohrer, C. Ushering in the era of tRNA medicines. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 105246 (2023).

Redig, A. J. & Janne, P. A. Basket trials and the evolution of clinical trial design in an era of genomic medicine. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 975–977 (2015).

Tao, J. J., Schram, A. M. & Hyman, D. M. Basket studies: redefining clinical trials in the era of genome-driven oncology. Annu. Rev. Med. 69, 319–331 (2018).

Lahey, H. G. et al. Pronounced therapeutic benefit of a single bidirectional AAV vector administered systemically in Sandhoff mice. Mol. Ther. 28, 2150–2160 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. BCKDHA–BCKDHB digenic gene therapy restores metabolic homeostasis in two mouse models and a calf with classic maple syrup urine disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eads0539 (2025).

Evans, M. E., Clark, W. C., Zheng, G. & Pan, T. Determination of tRNA aminoacylation levels by high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e133 (2017).

Behrens, A., Rodschinka, G. & Nedialkova, D. D. High-resolution quantitative profiling of tRNA abundance and modification status in eukaryotes by mim-tRNAseq. Mol. Cell 81, 1802–1815 (2021).

Santos, E. W. et al. Hematological and biochemical reference values for C57BL/6, Swiss Webster and BALB/c mice. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 53, 138–145 (2016).

Loeb, W. F. & Quimby, F. W. The Clinical Chemistry of Laboratory Animals, 2nd edn. (CRC Press, 2017).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the Viral Vector Core at UMass Chan for supporting AAV vector production and the Morphology Core at UMass Chan for conducting histopathological analyses. This study was funded in part by a UMass Chan BRIDGE Fund Award to D.W. The D.W. lab is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (P01HL158506).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.X., H.L. and D.W. conceptualized the study. M.X. designed and conducted the majority of experiments. H.L. designed and generated the CymR stable cell lines. J.W. contributed to vector genome design. A.F.V., M.P.G.-P. and V.K. conducted the MS and analyzed the data. X.Z. performed the initial screen of sup-tRNA candidates. N.L. produced the AAV vectors. J.L., A.D. and X.C. contributed to the mouse work. R.X. contributed to generation of the IduaW401X(TGA) mouse model. Y.Y. contributed to research design and data analysis. D.W. supervised the study. M.X. and D.W. analyzed data and wrote the original draft with input from H.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.X., H.L., J.W. and D.W. are inventors on a patent application filed by University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School related to the subject of this study. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biotechnology thanks Qing Xia and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Evaluation of UGA-sup-tRNAArg candidates in HEK293 cells.

(a) Schematics showing the sup-tRNA construct with a U6 promoter and the dual-luciferase (dual-luc) PTC reporter construct. CLuc: Cypridina luciferase. T2A: Thosea asigna virus 2 A peptide. GLuc: Gaussia luciferase. pA: polyadenylation signal. (b) Bar graph showing the readthrough efficiency as quantified by measuring GLuc activity normalized to CLuc activity in the culture medium. (c) Schematics showing the tandem (2x) sup-tRNA gene constructs with either a U6 promoter (U6-sup-tRNA) or a natural flanking sequence (NFS-sup-tRNA), and the digenic PTC reporter construct with a bi-directional promoter (BiP) driving the expression of mutant Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) and Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein with a FLAG tag (EGFP-FLAG), both of which are disrupted with an in-frame TGA nonsense mutation. pA: polyadenylation signal. (d) Workflow of the in vitro readthrough assay with plasmid co-transfection in HEK293 cells. (e) Bar graph showing the readthrough efficiency as quantified by measuring GLuc activity in the culture medium. (f) Bar graph showing the readthrough efficiency as quantified by measuring EGFP fluorescence signal in HEK293 cells. (g) Representative EGFP fluorescence images of HEK293 cells transfected with indicated plasmids. Scale bar: 200 µm. In b, e, f, protein expression from HEK293 cells transfected with a WT reporter plasmid (no TGA nonsense mutations) and an mCherry-only plasmid (no sup-tRNA) was defined as 100%. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Schematic in d created in BioRender. Zou, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/dqjni51.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The low-cis triple transfection method is more limited in packaging UGA-sup-tRNAs with augmented readthrough capabilities.

(a) Schematics showing the differences between standard triple transfection and low-cis triple transfection. The three plasmids (pHelper, pTrans, pCis) with the key elements involved in rAAV production are illustrated. (b) Bar graph showing the rAAV titers in the crude lysates of HEK293 cell cultures when packaging indicated pCis with various input amount. Data are normalized to the titer of rAAV9.mCherry produced with 100% pCis in parallel (defined as 100%) and presented as percentages. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. (c) Western blot images showing the Cap (top), Rep (middle), and GAPDH (bottom, serving as the loading control) protein expression in HEK293 cells undergoing rAAV9 production with indicated pCis and amount. 3 independent experiments were conducted.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The CuO-CymR system suppresses UGA-sup-tRNA function.

(a) Schematics showing the constructs expressing NFS-sup-tRNA with a tetracycline operator (TetO) inserted immediately or 20 bp upstream of the leader sequence (L, 6 bp), and the construct expressing tetracycline repressor (TetR). (b) Representative images of EGFP fluorescence in transfected HEK293 cells (left) and quantification of GLuc activity in culture medium (right) to measure readthrough efficiency following co-transfection of indicated plasmids. When the TetR plasmid was not included (- TetR), a plasmid expressing mCherry was used instead to keep the total amount of DNA in co-transfection the same. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed with two-sided t-test. (c) Schematics showing the constructs expressing NFS-suptRNA with a cumate operator (CuO) inserted upstream of the mature sup-tRNA template sequence at indicated position and orientation, and the construct expressing Cym repressor (CymR). (d) Representative images of EGFP fluorescence in transfected HEK293 cells (left) and quantification of GLuc activity in culture medium (right) to measure readthrough efficiency following co-transfection of indicated plasmids. When the CymR plasmid was not included (- CymR), a plasmid expressing mCherry was used instead to keep the total amount of DNA in co-transfection the same. In b and d, each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed by two-sided unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Generation and characterization of CymR clonal cell lines.

(a) Schematics showing the gene editing strategy to integrate the CymR gene into the AAVS1 locus in HEK293 cells. SgRNA: single guide RNA. LHA: left homology arm. SA: splicing acceptor. P2A: Porcine teschovirus-1 2 A peptide. T2A: Thosea asigna virus 2A peptide. PuroR: puromycin resistance gene. bGHpA: bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal. RHA: right homology arm. (b) Cartoon showing the procedure to generate the CymR stable cell pool. (c) Cartoon showing the mechanism of CuO/CymR-controlled EGFP reporter. In the absence of cumate (left), CuO-CymR binding blocks EGFP expression. In the presence of cumate (right), it binds to CymR, preventing the inhibitory effect on EGFP expression. (d) EGFP fluorescence images from HEK293 or various clonal cell lines transfected with the CuO/CymR-controlled EGFP reporter plasmids in the absence or presence of cumate at 30 µg/mL. The screening was performed once. (e) Tabulation of large-scale production yield of rAAV9.2xCuO-hNFS-R8 with CymR clonal cell lines. Vg: vector genome.

Extended Data Fig. 5 CymR cell lines improves AAV9 vector yield when packaging additional UGA-sup-tRNAArg genes and a UAA-sup-tRNA gene.

(a) Assessment of the readthrough capabilities of three UGA-sup-tRNAArg designs (hNFS-R8, hNFS-tRT5, OptACE-tRNAArgUGA) using the digenic PTC reporter system in HEK293 cells. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. (b) Assessment of readthrough capabilities using the dual luciferase (dual-luc) PTC reporter system in HEK293 cells. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). (c) Bar graph showing the crude lysate titers of rAAV9 vectors packaging various UGA-sup-tRNAArg genes without (-) or with (+) CuO, in unmodified HEK293 cells (HEK) or the M20 cell line. Each vector genome contains one copy of the indicated sup-tRNA cassette. Data are normalized to the titer of rAAV9.mCherry produced with 100% pCis in unmodified HEK293 cells in parallel (defined as 100%) and presented as percentages. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. (d) Schematics showing the tandem (2x) UAA-sup-tRNA gene construct with its mouse natural flanking sequence (mNFS). (e) Bar graph showing the rAAV9.2xCuO-mNFS-UAA-sup-tRNA titers in the crude lysates of HEK293 or various CymR monoclonal cell line cultures in the absence or presence of the CymR plasmid. Data are normalized to the titer of rAAV9.CMV/CB-CuO-mCherry produced with 100% pCis in parallel (defined as 100%) and presented as percentages. Each dot represents a biological repeat (n = 2).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Characterization of truncated vector genomes by single-molecule nanopore sequencing.

(a) Coverage plot of the sequencing reads mapped to the reference vector genome (VG). The vector genome elements are illustrated to scale. (b) Virtual gel image generated with the sequencing reads mapped to the reference VG. For truncated vector genomes, the lost DNA elements due to recombination are illustrated with dashed borders. A single AAV preparation lot was used for each vector.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Generation and characterization of the Idua-W401X(TGA) mouse model.

(a) Schematics showing a portion of the mouse Idua gene. The sequences of both the wildtype (WT) allele and the knock-in (KI) allele are shown. In the KI allele, the G-to-A mutation is colored in red, and the resulting TGA nonsense mutation is underlined. The Sanger sequencing chromatograph for the KI allele is shown at the bottom, with the G-to-A mutation highlighted in red background. (b) Bar graph showing the iduronidase (IDUA) enzymatic activity levels in the liver and heart from WT (Idua+/+) and homozygous KI (IduaKI/KI) mice. Data are presented as percentage of the WT levels. (c) Bar graph showing the Idua mRNA levels in the liver and heart from WT and homozygous KI mice normalized to Tbp mRNA levels. (d) Determination of the amino acid residues incorporated by sup-tRNA-mediated readthrough at codon 401 by mass spectrometry. A schematics showing the workflow is shown on the left, and a pie chart showing detected amino acids and their percentages is shown on the right. (e) Schematics showing the workflow of in vitro assessment of IDUA variants with different residues at codon 401 for their expression and enzyme activities. (f) Western blot image showing the expression levels of IDUA variants with a FLAG tag at the C-terminus in patient fibroblasts transfected with individual mIdua cDNA constructs. The amino acid residues encoded by codon 401 are labelled with three-letter and single-letter abbreviations. X denotes the mIdua cDNA construct with a TGA at codon 401. (g) Quantification of the anti-FLAG signal intensity in the western blot as shown in (f). Data are normalized to the WT mIdua cDNA encoding Trp at codon 401. (h) IDUA activity in patient fibroblasts transfected with various mIdua cDNA constructs. (i) Specific IDUA activity (that is, IDUA activity normalized to protein expression level) from various mIdua cDNA constructs. Data are normalized to the Trp construct as 100%. In b and c, each dot represents an individual animal (n = 3 or 4). In f-i, each lane or dot represents a biological repeat (n = 3). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed with two-sided t-test in b and c, and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test in i. Schematic in e created in BioRender. Zou, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/dqjni51.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Durable efficacy in IduaKI/KI mice at 20 weeks post-treatment.