Abstract

The biological mechanisms through which most nonprotein-coding genetic variants affect disease risk are unknown. To investigate gene-regulatory mechanisms, we mapped blood gene expression and splicing quantitative trait loci (QTLs) through bulk RNA sequencing in 4,732 participants and integrated protein, metabolite and lipid data from the same individuals. We identified cis-QTLs for the expression of 17,233 genes and 29,514 splicing events (in 6,853 genes). Colocalization analyses revealed 3,430 proteomic and metabolomic traits with a shared association signal with either gene expression or splicing. We quantified the relative contribution of the genetic effects at loci with shared etiology, observing 222 molecular phenotypes significantly mediated by gene expression or splicing. We uncovered gene-regulatory mechanisms at disease loci with therapeutic implications, such as WARS1 in hypertension, IL7R in dermatitis and IFNAR2 in COVID-19. Our study provides an open-access resource on the shared genetic etiology across transcriptional phenotypes, molecular traits and health outcomes in humans (https://IntervalRNA.org.uk).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The majority of genetic variants associated with common diseases and other complex traits identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) lie in nonprotein-coding sequences1. Consequently, the molecular mechanisms that underpin many of these genotype–phenotype associations are unclear. Molecular quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping studies, which identify genetic determinants of transcript, protein or metabolite abundance, can address this knowledge gap by identifying the molecular intermediaries that mediate genetically driven disease risk. These studies can provide specific hypotheses for functional validation experiments2,3.

Molecular QTL data can be used for a range of biomedical applications. For example, they have the potential to identify and validate new therapeutic targets and pathways, inform about the biological mechanisms of drug action and safety, highlight new therapeutic indications and reveal clinically relevant biomarkers4,5,6.

Many previous studies have carried out QTL mapping within a single molecular domain such as gene or protein expression7,8,9,10,11,12. However, QTL data from multi-omic modalities are needed to fully understand the causal molecular chain of events from genetic variation to complex trait phenotypes13. Moreover, the availability of multimodal data in a single population sample enhances the interpretation and validity of causal inference analyses. For example, mediation analysis in a single cohort presents a strategy for identifying phenotypes that share a common genetic pathway and quantifying the proportion of the total genetic effect on those phenotypes14.

Here we use the INTERVAL study15,16, a bioresource of approximately 50,000 blood donors with extensive multidimensional ‘omics’ profiling, to identify gene expression and splicing QTLs based on peripheral blood RNA sequencing (RNA-seq; n = 4,732 individuals). Then, we integrate the QTL data with additional molecular QTL data derived from the same study (Fig. 1). These data include plasma protein levels measured through an antibody-based proximity extension assay (Olink Target panels, n = 4,662–4,981 individuals)17,18 and an aptamer-based multiplex protein assay (SomaScan v3, n = 3,301)5, as well as serum metabolite levels measured using an untargeted mass spectrometry platform (Metabolon HD4, n = 14,296)10 and a nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy platform (Nightingale Health, n = 40,849)19,20.

The images depicting ‘genotypes’ (the figure is created with NIAID NIH Bioart) and ‘proteins’ (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 2F6W) were reproduced from public databases. COVID-19 HGI, COVID-19 host genetics initiative; MAF, minor allele frequency.

Our data reveal genetic effects on the expression and splicing of local and distant genes. We assess shared genetic etiology across molecular traits and health outcomes using statistical colocalization. We further investigate the genetic effects on downstream molecular phenotypes through transcriptional events by conducting mediation analyses. Based on these analyses, we develop an open-access portal that enables exploration of this compendium of molecular QTLs (https://IntervalRNA.org.uk).

Results

Genetic regulation of local gene expression and splicing

We performed bulk RNA-seq on peripheral blood collected from 4,732 blood donors recruited as part of the INTERVAL study (Methods). The expression levels of 19,173 autosomal genes and 111,937 de novo transcript splicing phenotypes (herein referred to as ‘splicing events’) from differential intron usage ratios in 11,016 genes were quantified. Then, we mapped local (cis) expression QTLs (eQTLs) within ±1 Mb of the transcription start site (TSS) and splicing QTLs (sQTLs) within ±500 kilobase pairs (kb) of the center of the spliced region.

We identified 17,233 genes (89.9% of the 19,166 tested) with at least one significant cis-eQTL (cis-eGene) at a false-discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2; Methods). Stepwise conditional analyses for each cis-eQTL revealed 56,959 independent signals (53,457 unique lead variants), with a median of three independent signals per gene (range = 1–23; Supplementary Tables 1 and 3; Methods). We compared our results to those from the eQTLGen consortium study given in ref. 9 (n = 31,684 individuals). z scores from eQTL lead SNPs were highly correlated between these studies (Pearson’s r = 0.9; Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 4), highlighting the consistency of eQTL discovery results across independent datasets and mapping technologies.

Next, we identified 29,514 splicing events with a cis-sQTL at FDR < 0.05 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 5). These splicing events with a cis-sQTL were mapped to 6,853 genes (cis-sGenes) with a median of three splicing events observed per cis-sGene (range = 1–128). This included 543 cis-sGenes that were not identified as cis-eGenes. Across all splicing events with cis-sQTLs, these had a median length of 1,549 base pairs (bp) and excised a protein-coding sequence in 32.4% of cases (the remainder related to intronic and UTR excisions). The median distance from the cis-sQTL lead variants to the center of the splicing event was 187 bp upstream, with lead variants forming a bimodal distribution around the start and end of the sGene (Fig. 2a).

a, Distribution of lead variants at cis-eQTLs and cis-sQTLs around the TSS and gene body (normalized to the median gene length of 24 kb). b, Schematic representation of the trans-QTL mapping analysis approach and summary of the QTL discovery results. c, Circos plot of the trans-splicing of 18 sGenes by the cis-eQTL for QKI. TES, transcription end site.

After conditional analysis for each cis-sQTL, we identified 47,050 independent signals (34,205 unique lead variants), with a median of one independent signal per cis-sQTL (range = 1–20; Supplementary Tables 1 and 6). To characterize independent variant effects on transcript splicing, we compared primary (that is, the most significant independent QTL) and secondary (that is, all other independent QTLs) cis-sQTLs. Primary cis-sQTL signals were enriched within the gene body of sGenes compared to secondary signals (P = 2.84 × 10−314, chi-squared test; Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Primary cis-sQTL signals were more enriched toward the transcription end site (median of 17.36 kb downstream of the TSS) compared to cis-eQTLs with a median of 5.51 kb downstream of the TSS (P = 8.42 × 10−259, two-sided Wilcoxon test; Supplementary Fig. 2). These observations align with previous analyses for isoform ratio QTLs21. Next, we compared the identified sGenes with those from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Consortium22 whole-blood dataset (n = 670 individuals). Of the 3,013 sGenes discovered by GTEx, 89.0% of the 2,677 we tested were also found as sGenes in our analysis, in addition to 4,470 new sGenes (Supplementary Table 7). These results demonstrate the value of quantifying de novo splicing excision events and the substantially larger sample size.

For a given gene, to test whether corresponding cis-eQTLs and cis-sQTLs were underpinned by the same genetic variant, we performed colocalization analyses. This revealed 3,979 genes (of 6,252 tested) with colocalized signals (Methods). We found that 49.0% (n = 13,490) of tested splicing events had sQTLs that colocalized with an eQTL for the same gene (Supplementary Table 8). However, of the eQTL-colocalizing splicing events with multiple independent sQTL signals, 82% had additional sQTL loci that did not colocalize with eQTLs. Splicing events with sQTL that did not colocalize with an eQTL were located further downstream of the TSS (median 20.33 kb downstream) compared to sQTL signals that did colocalize (median 12.61 kb downstream; P = 9.8 × 10−70, two-sided Wilcoxon test; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Genetic effects on distal gene expression and splicing

Next, we investigated the distal (trans) regulatory effect of genetic variants (>5 Mb from the TSS/splicing event). First, we performed an untargeted, all-versus-all trans-eQTL and trans-sQTL analysis. We found a high correlation of trans-eQTL z scores for SNP–gene pairs also tested by the eQTLGen consortium study9 (Pearson’s r = 0.9; Supplementary Fig. 4). As our study has lower statistical power than eQTLGen, we focused on replicating the 2,924 most significant trans-eQTL associations from eQTLGen with P < 1 × 10−20. Of these, we replicated 63% at P < 1 × 10−6 in INTERVAL. We note that the incomplete overlap may be due to differences in data analysis strategies, including accounting for blood cell counts in the association model9.

Given the extreme multiple testing burden for genome-wide trans-QTL analyses, we focused on the 53,457 conditionally independent lead cis-expression SNPs (eSNPs), as these provide a potential mechanism through which a cis-acting variant can also affect genes in trans. In this targeted analysis, we identified 2,058 trans-eGenes at the Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 5 × 10−11 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and 9). These trans-eQTLs corresponded to 2,498 cis-eQTLs, with a median of three trans-eGenes per cis-eQTL (range = 1–284). Some of the cis-eGenes were associated with many trans-eGenes, such as PLAG1 (n = 284 genes), HYMAI (n = 284) and FUCA2 (n = 267). Cis-eGenes with a concurrent trans-association were significantly enriched for 32 gene ontology (GO) terms, compared to all cis-eGenes. Most of the terms related to transcription regulation and immune response, with ‘metal ion binding’ showing the strongest enrichment (P = 2.6 × 10−30; Supplementary Table 10). To further explore these transcriptional regulation mechanisms, we annotated the genes using the Human Transcription Factors database23. We found a significant enrichment in sequence-specific transcription factors, representing 14.3% of all cis-eGenes with a trans-association (357/2,498, P = 1.83 × 10−38; Methods). We investigated protein domain annotations for the observed transcription factors and detected a significant enrichment for the C2H2 zinc finger domain (P = 9.74 × 10−9 after Bonferroni multiple-testing correction), specifically with the Krüppel-associated box domain (P = 3.04 × 10−10; Supplementary Fig. 5). For example, the PLAG1 gene, which is an important regulator of the human hematopoietic stem cell dormancy and self-renewal24, codes for a protein with a C2H2 zinc finger domain. We also noted the same enrichment for trans-eGenes (P = 5.73 × 10−5), although the molecular mechanisms are unclear and need further investigation.

To uncover genetic expression effects impacting distal downstream transcript splicing, we performed a targeted trans-analysis using the same 53,457 conditionally independent lead cis-eSNPs as in the trans-eQTL analysis. The analysis identified significant trans-associations for 644 splicing events (209 trans-sGenes) at the Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 8.36 × 10−12. This comprised 758 unique trans-splicing SNPs (sSNPs), corresponding to 566 cis-eGenes (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 11). Of the 644 splicing events regulated in trans, 240 (in 91 genes) were not observed to be regulated in cis, increasing the total number of splicing events with QTLs. We observed 11 cis-eGenes that were implicated by their cis-eQTLs in the regulation of more than ten sGenes in trans. For example, we observed that the cis-eQTL for the RNA-binding splice factor QKI was associated with 18 sGenes in trans (the most of any eGene; Fig. 2c). Across all tissues in GTEx, there were only 29 trans-sQTL associations, of which only two were present in whole blood, that is, the trans-splicing of FYB1 via the QKI cis-eQTL and the trans-splicing of ABHD3 for which they did not detect an associated cis-effect for the trans-sSNP22. Here we replicated both of these previous trans-sGene observations. For ABHD3, we demonstrate in addition that this trans-sSNP is also a cis-eSNP for the splicing factor TFIP11 and its antisense long noncoding RNA TFIP11-DT, potentially regulating the splicing of this gene in trans. Reports of the preliminary overlap of trans-sQTL associations with previous experimental validation are given in Supplementary Note and Supplementary Table 12. Across the whole dataset, cis-eGenes of trans-sSNPs were significantly enriched for ten GO terms, including ‘nucleosome assembly’ (P = 2.78 × 10−6) and ‘RNA polymerase II activity’ (P = 1.40 × 10−5; Supplementary Table 10).

Shared genetic etiology across molecular traits

We next compared transcriptional QTLs to the other omics QTLs derived from subsets of participants from the INTERVAL study. These data include plasma protein QTLs (pQTLs) from the Olink Target and SomaScan panels, as well as metabolite QTLs (mQTLs) from the Metabolon and Nightingale Health platforms.

To determine whether genetic signals at a given locus across omics layers reflect shared genetic or distinct causal variants, we performed statistical colocalization analyses (Methods). These analyses revealed colocalization between either a cis-eQTL or cis-sQTL and cis-QTL for 120 Olink-measured proteins (65.9% of analyzed proteins), 404 SomaScan-measured proteins (63.7%), 224 Nightingale-measured metabolites (99.1%) and 495 Metabolon-measured metabolites (81.5%; Fig. 3a and Supplementary Tables 13–16). We found colocalized signals across all assessed proteomic and metabolomic traits for 1,229 cis-eGenes and 649 cis-sGenes (1,516 unique genes). For Olink- and SomaScan-measured proteins, genetic effect directions were more consistent (P = 5.4 × 10−10, one-sided Fisher’s exact test) for colocalizing eQTL–pQTL pairs (78.9% with consistent effect directions) than noncolocalizing pairs (59.0%). The uncoupling of eQTLs and pQTLs has previously been observed25 and could be due, for example, to post-transcriptional or post-translational mechanisms.

Of the 99 eQTL–pQTL pairs (364 sQTL–pQTL pairs) analyzed for colocalization in both Olink and SomaScan platforms, we found that 45 (127) had a colocalized signal in both platforms, 19 (57) on the Olink platform only and 9 (41) on the SomaScan platform only (Supplementary Tables 17 and 18). We annotated these colocalization results with cross-assay correlations reported previously26 and found significantly higher cross-assay correlations for eQTL/sQTL–pQTL pairs with a colocalized signal for both platforms compared to eQTL–pQTL pairs with a colocalized signal for only one platform (eQTL–pQTL pairs, P = 3.1 × 10−4; sQTL–pQTL pairs, P = 1.4 × 10−7; one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). This indicates that the differences we observed in colocalization results might be due to differences in protein measurements between the two platforms.

Next, we created a network to explore and visualize the interconnectedness among colocalized transcriptional and molecular phenotypes (Fig. 3b), linking each phenotype by their colocalizations. For example, we found seven splicing events in the OAS1 gene with cis-sQTLs that colocalized with both the cis-eQTLs for this gene and the OAS1 pQTLs.

To investigate the potential mechanisms by which genetic variants impact protein levels through splicing, we annotated the protein domains affected by splicing events. We observed that nearly half of splicing events that colocalized with pQTLs (41.0%, 401 of 977) excised annotated protein-coding sequences. Splicing has been shown to modulate circulating protein levels through changes in secretion by the inclusion or exclusion of transmembrane domains27. This is exemplified by a splicing event that removes exon 6 of the FAS gene, a cell surface receptor for the FAS-ligand (FASL) cytokine. The resulting protein, lacking a transmembrane domain, is secreted28 and competitively inhibits FASL binding, leading to decreased apoptosis. We identified both cis-eQTLs for FAS and cis-sQTLs for this splicing event, but these signals were distinct and did not colocalize (maximum posterior probability = 0.02). The cis-sQTLs for excision of the transmembrane domain strongly colocalized with the pQTL (posterior probability = 1.00). Similarly, the interleukin-6 and interleukin-7 receptors (IL-6R and IL-7R, respectively) have previously been reported to produce secreted isoforms through the excision of transmembrane domains29,30. Here we show that the pQTLs for IL-6R and IL-7R colocalized with cis-sQTLs excising these transmembrane domain-encoding exons, in the absence of cis-eQTL colocalization (Fig. 3b). This observation emphasizes the role of transcript splicing as a mechanism independent of total transcript abundance through which genetic variation can modify downstream molecular phenotypes. Furthermore, we observed a pQTL colocalizing with an sQTL for the excision of a transmembrane domain in the encoding messenger RNA (mRNA) in 69 proteins (98 unique splicing events), with 60.2% of these independent sQTL signals (n = 100/166) not colocalizing with eQTLs for the same gene (Supplementary Table 19). For example, this is observed in α-1 antitrypsin encoded by SERPINA1 and apolipoprotein L1 encoded by APOL1. Of these 69 transmembrane proteins, the majority were annotated as being single-pass, with only four (ENTPD1, ADGRE2, ADGRE5 and ADGRE1) being multipass transmembrane proteins.

To maximize statistical power for colocalization, we extended our analyses to the SomaScan-pQTL and Olink-pQTL datasets from deCODE8 (n = 35,559 individuals and n = 4,719 proteins) and the UK Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project12 (UKB-PPP; n = 54,219 individuals and n = 2,941 proteins), respectively. Colocalization analyses were performed between 1,608 Olink- and 1,410 SomaScan-measured proteins and our transcriptional phenotypes, increasing the discovery of pQTL–eQTL/sQTL colocalizations from 120 to 1,203 Olink-measured proteins and from 404 to 984 SomaScan-measured proteins. We observed a substantial overlap of eGenes and splicing events with QTLs colocalizing between our internal and the larger external pQTL cohorts. In UKB-PPP, we replicated 95.1% and 79.3% of eQTLs and sQTLs colocalizations, respectively, and in deCODE, 87.0% and 80.3% of eQTLs and sQTLs, respectively (Supplementary Tables 13–15; web portal).

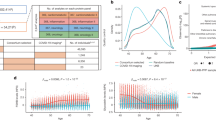

Mapping causal transcriptional events on molecular phenotypes

To assess the causality of the transcriptional phenotypes on downstream molecular phenotypes, we performed mediation analyses focusing on colocalizing molecular traits assayed in the INTERVAL study (Fig. 4a; Methods). The expression of 143 cis-eGenes significantly mediated the effect of 413 cis-eSNPs on 202 downstream molecular phenotypes, including 101 SomaScan-measured proteins, 54 Olink-measured proteins, 39 Nightingale-measured metabolites and 8 Metabolon-measured metabolites. In total, this comprised 525 significant eQTL mediation models (variant-gene-molecular phenotype triplets; Fig. 4b). Similarly, we observed 106 splicing event phenotypes in 47 sGenes that significantly mediated the effect of 152 cis-sSNPs on 50 downstream molecular phenotypes, including 32 SomaScan-measured proteins, 16 Olink-measured proteins, 1 Nightingale-measured metabolite and 1 Metabolon-measured metabolite, comprising 241 significant sQTL mediation models (Supplementary Tables 20 and 21).

a, Schematic representation of the tested mediation model, for which eQTL and sQTL phenotypes mediate the relationship between genomic variants and levels of molecular phenotypes. The images depicting ‘independent genomic variants’ (the figure is created with NIAID NIH Bioart) and ‘molecular phenotypes’ (PDB code 2F6W) were reproduced from public databases. b, Total number of detected molecular phenotypes mediated by sQTLs and eQTLs. c, Colocalization of sQTLs excising the transmembrane domains of the interleukin receptors IL6R and IL17RA and mediation with plasma protein quantities (n = 3,024 for IL17RA and n = 3,072 for IL6R). The central point represents the mediation effect estimate. Error bars represent the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the estimated effects. d, Schematic representation of the splicing events excising transmembrane domains of the interleukin receptors IL6R and IL17RA.

Previous reports showed that the missense variant rs2228145 affects IL-6R ectodomain shedding by the alteration of one of the cleavage sites of ADAM10/ADAM17 metalloproteinases31,32. In line with this finding, we observed the previously mentioned IL6R transmembrane splicing event mediated a minority of the effect of the lead SNP (rs12126142), which is in high LD (r2 > 0.99; D′ > 0.99) with this missense variant, on Olink-measured plasma protein abundance (4.67%, P = 1.12 × 10−4; Fig. 4c,d). This suggests a potential dual action of the sSNP or tagged variants on removing this domain and, hence, creating a soluble isoform by both splicing and proteolytic pathways. Conversely, the colocalized signal (lead cis-sSNP rs34495746) between splicing of the transmembrane domain of IL17RA and levels of its plasma protein was found to have most of the effect mediated by transcript splicing (90.41%, P = 1.14 × 10−43; Fig. 4c). Consistent with this observation, neither the lead SNP nor any strong tagging SNPs (r2 > 0.8) were missense variants.

Deconvoluting molecular mechanisms underlying GWAS loci

Molecular QTLs can provide insights into the mechanisms underlying genetic variants that influence disease risk33. We performed colocalization analyses with genetic association signals for 20 disease phenotypes from the FinnGen project (release 9)34, prioritized based on their relevance to the circulatory system and available sample size (that is, ≥1,000 cases; Supplementary Table 22).

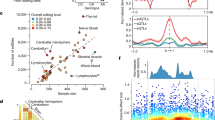

Disease-associated signals colocalized with 649 cis-eGenes and 365 cis-sGenes (1,035 splicing events) across all tested traits (Supplementary Tables 23 and 24). Many of these independent signals (136/981 for cis-eQTLs and 304/1589 for cis-sQTLs) also colocalized with pQTLs and mQTLs, revealing the regulatory pathways underlying the complex trait-associated variants. For example, a cis-sQTL for the transmembrane domain splicing of IL7R colocalized with an association locus for dermatitis and eczema, as well as a pQTL for IL-7R in UKB-PPP (Fig. 5a). This analysis implicates soluble isoforms of IL-7R generated by alternative splicing in this condition. The alternative allele of rs6897932 (T) is associated with decreased excision of the IL7R transmembrane domain, lower levels of IL-7R in plasma and reduced risk of dermatitis and eczema. This allele has been previously shown to associate with decreased lymphocyte count35 and decreased risk of multiple sclerosis36, suggesting consistent therapeutic implications.

a, Putative pathways and directions of the effect of sQTL signals for IL7R and WARS1 associated with plasma protein quantity, dermatitis and eczema, and hypertension, respectively. The image depicting ‘soluble protein’ was reproduced from a public database (PDB code 2F6W). b, Gene-level summary of colocalization of cis-eQTL and cis-sQTL with COVID-19 HGI summary statistics. The red dashed line represents genome-wide significance (P = 5 × 10−8) and the height toward the center represents the significance of the GWAS association. c, Example of a multitrait colocalization for COVID-19 in OAS1, with GWAS summary statistics, cis-pQTL, cis-eQTL and cis-sQTL.

Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (encoded by WARS1) exists in both secreted and intracellular forms37, with downstream impacts on vascular permeability38. Here we found a cis-sQTL for excision of exon 10 of WARS1 (encoding a portion of the tRNA synthetase protein domain), which colocalized with both the WARS1 pQTLs and risk for hypertension in FinnGen (Fig. 5a). The alternative allele of rs724391 (C) is associated with decreased excision of exon 10, higher plasma protein levels of WARS1 and increased risk of hypertension.

Finally, we also performed a genetic look-up analysis of all independent signals at the identified cis-eQTLs and cis-sQTLs using data from the Open Target Genetics Portal (v22.10). We present the results on our web portal.

Transcriptional mechanisms underlying COVID-19 GWAS loci

Most of the whole-blood RNA is derived from circulating immune cells. Given the importance of the host immune response in COVID-19, we conducted colocalization analyses of the identified eQTLs and sQTLs with genetic loci associated with COVID-19 susceptibility and severity available from the pan-biobank COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative39. We found colocalized signals with COVID-19 loci for 67 cis-eGenes and 42 cis-sGenes (91 splicing events; Supplementary Tables 25 and 26 and Fig. 5b), of which 17 overlapped.

Previous analyses have identified genetic variants that impact splicing of OAS1 (refs. 40,41). These variants have subsequently been implicated in influencing COVID-19 severity41. Consistent with these data, we observed colocalization of an eQTL and sQTLs for seven splicing events at the OAS1 locus with COVID-19 (Fig. 5c). Adjusting for OAS1 gene expression levels did not ablate the sQTL signals (P < 1 × 10−16), suggesting the presence of multiple independent transcriptional mechanisms at this locus. In addition, we found colocalization for these eQTLs and sQTLs with the OAS1 pQTL, suggesting that genetic variants mediate disease risk through transcriptional changes impacting soluble protein levels.

Furthermore, the GWAS signals for COVID-19 susceptibility and severity at the IFNAR2 locus (encoding the interferon α/β receptor 2) colocalized with a cis-eQTL, and cis-sQTLs associated with 10 splicing events in this gene (Supplementary Fig. 6). This included a splicing event excising exons 8 and 9, encoding the IFNAR2 transmembrane domain. Rare (stop–gain) mutations in exon 9 of this gene leading to loss of function have been previously reported to increase the risk of severe COVID-19 infection42. While IFNAR2 was not measured by the proteomic assays, isoforms of IFNAR2 lacking the transmembrane domain are known to generate a soluble protein isoform43, and significantly higher quantities of soluble IFNAR2 have been observed in the serum of patients with severe COVID-19 (ref. 44). However, the role of splicing in this gene on disease severity has not been previously reported. Notably, the colocalizing IFNAR2 eQTLs are also trans-sQTLs for five splicing events in IFI27, four of which do not have an association in cis. Our results provide evidence for a mechanism whereby common variants regulating splicing of IFNAR2 could be contributing to disease severity through impacts on protein solubility.

Discussion

Nonprotein-coding genetic variants have an important role in the genetics of complex traits, accounting for 90% of common trait heritability45. Genome-wide, multilayered molecular QTL data can help elucidate the functional impact of trait-associated variants and their regulatory networks that underpin complex disease biology. To this end, we discovered eQTLs for 17,233 genes and sQTLs for 29,514 splicing phenotypes in 6,853 genes in peripheral blood through RNA-seq of 4,732 individuals. This included nonprimary signals for 81% of cis-eGenes and 49% of cis-sGenes, substantially increasing knowledge of the independent genetic determinants of gene expression in whole blood. We combined these data with mQTL and pQTL data in the same participants of the INTERVAL study to map the genetic basis for disease phenotypes. Notably, 52% of independent eQTL colocalizations and 28% of significant mediations involved nonprimary eQTL signals. Similarly, 31% of independent sQTL colocalizations and 30% of significant mediations involved nonprimary sQTL signals. These data demonstrate the value of the conditional analysis performed. Finally, we performed a downsampling analysis to provide guidance toward the expected eQTL and sQTL discovery for future studies (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b).

In comparison to eQTLs, the genetic determinants of splicing have been less thoroughly explored, in particular, how they impact downstream molecular phenotypes and disease risk. Our data support previous findings that splicing QTLs are major contributors to complex traits46. Through mapping sQTLs alongside eQTLs, we identified additional independent mechanisms by which genetic variants can influence mRNA and protein levels. For example, the 98 splicing events that colocalized with pQTLs (such as IL-6R and IL-7R) excised protein-coding sequences encoding transmembrane domains. Many of these pQTLs did not colocalize with eQTLs, suggesting that the sQTLs provide the pivotal mechanistic insight, given that genetic effects on splicing are more highly shared between tissues than genetic effects on expression22. Furthermore, by identifying and using de novo excision events from the RNA-seq data, we increased the resolution beyond established transcript annotations.

Using the multi-omic data in the INTERVAL study, we systematically performed mediation analyses to evaluate causality in the context of colocalized genetic association signals with molecular traits. In total, we observed 222 molecular phenotypes significantly mediated by gene expression or splicing, providing an additional layer of evidence to delineate functional mechanisms. For instance, we found that an sQTL excising the extracellular domain of CD33 mediated most of the effect of the sSNP on CD33 soluble protein levels. Mediation analyses are important to define the mode of action of the genetic effects underlying association loci identified in GWAS, as well as the magnitude and direction of their relative effects on downstream phenotypes.

Our study has limitations. First, while we have focused on one definition of transcript splicing due to the annotation-free approach benefiting the downstream analyses, other methodologies may shed light on other aspects of transcript splicing. Second, statistical power was limited to mapping genome-wide eQTLs and sQTLs in trans. As trans-QTLs are challenging to replicate and distinguish from cell type heterogeneity in bulk RNA-seq studies9, we prioritized the identified conditionally independent lead cis-eSNPs for our trans-QTL analyses to prioritize the mechanism of upregulated gene expression modifying the expression and splicing of downstream genes. While we show a strong correlation of effect sizes for SNP–gene pairs also tested by the eQTLGen consortium (phase I), large-scale meta-analyses of trans-QTL datasets will be required to create a resource of replicated associations, such as that being prepared by the eQTLGen consortium (phase II; https://www.eqtlgen.org/). To aid in these efforts, we have provided full trans-QTL summary statistics on our web portal. Third, our analyses comprised proteins quantified in plasma, rather than intracellular proteins. Thus, the interpretation of the effects of gene expression and splicing QTLs on proteins may be due to impacts on both quantity and solubility of the resulting protein, and other regulatory mechanisms, such as the stability of the mRNA and protein in addition to translational efficiency, may not be captured. However, additional data would be needed to address this. Fourth, the intrinsic properties of the different molecular data types can create challenges in interpretation. For example, there is a considerable correlation structure between metabolite levels47. As such, we found that the majority of mQTLs (96%) colocalized with either a cis-eQTL or cis-sQTL. Conversely, mQTLs showed mediation by cis-eQTLs or cis-sQTLs less frequently than pQTLs (that is, 6.8% versus 32.6% for mQTLs and pQTLs, respectively). Finally, our cohort comprised individuals of European ancestry. More work is needed to establish the translatability of our findings to other ancestries.

Previous studies showed that local regulation of gene expression is largely shared across tissues48 and that larger, well-powered eQTL studies in a surrogate tissue may identify more trait-colocalizing eQTLs than smaller studies in the target tissue49. Hence, these results provide a scientific rationale for the generation of increasingly large-scale QTL data in easily accessible tissues, such as peripheral blood. In our study, we further demonstrate the value of such a dataset when integrating data from multiple molecular phenotypes in the same individuals and linking these to external health outcomes to help address the variant-to-function challenge. Similar application to population biobanks is warranted, and with the emerging availability of concomitant molecular data at the single-cell level across a wide range of tissues, single-cell-QTL mapping at the population scale will become feasible. Such data will enable us to dissect gene-regulatory networks at much greater resolution across specific cell types and dynamic processes50,51. Together, these improved molecular QTL data will further enhance the interpretation of GWAS signals52. While GWAS signals have previously been observed to be depleted for eQTLs53, we demonstrate that the broader approaches used in this study, such as the increased sample size, the resolution of nonprimary signals and the additional signals captured by the sQTLs, have the potential to increase discovery of the molecular mechanisms underlying GWAS association.

Methods

Study participants

The INTERVAL study is a prospective cohort study of approximately 50,000 participants nested within a randomized trial of varying blood donation intervals15,16. Between 2012 and 2014, blood donors aged 18 years and older were recruited at 25 centers of England’s National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT). All participants gave written informed consent before joining the study, and the National Research Ethics Service approved this study (11/EE/0538). Participants were generally in good health, as blood donation criteria exclude individuals with a history of major diseases (for example, myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, HIV and hepatitis B or C) and who have had a recent illness or infection. Participants completed an online questionnaire comprising questions on demographic characteristics (for example, age, sex and ethnicity), lifestyle (for example, alcohol and tobacco consumption), self-reported height and weight, diet and use of medications. Demographic details are provided in Supplementary Table 27.

Blood collection

Blood samples were collected from all INTERVAL participants at baseline and also from ~60% of participants ~24 months after baseline. For a subset of ~5,000 participants at the 24-month time point, an aliquot of 3 ml of whole blood was collected in Tempus Blood RNA Tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and then transferred at ambient temperature to the UK Biocentre. Samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

RNA extraction

RNA extraction was performed by QIAGEN Genomic Services using QIAGEN’s proprietary silica technology. The quality control (QC) of the extracted RNA was performed by spectrophotometric measurement on an Infinite 200 Microplate Reader (Tecan). RNA integrity number (RIN) values were determined using a TapeStation 4200 system (Agilent), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples with a concentration <20 ng μl−1 and a RIN value <4 were excluded from further analyses.

Automated RNA-seq library preparation

Samples were quantified with a QuantiFluor RNA System (Promega) using a Mosquito LV liquid handling platform (SPT Labtech), Bravo automation system (Agilent) and FLUOstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech) and then cherry-picked to 200 ng in 50 μl (=4 ng μl−1) using a liquid handling platform (Tecan Freedom EVO). Next, mRNA was isolated using a NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biosciences, NEB) and then resuspended in nuclease-free water. Globin depletion was performed using a KAPA RiboErase Globin Kit (Roche). RNA library preparation was done using a NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB) on a Bravo NGS workstation automation system (Agilent). PCR was performed using a KapaHiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche) and unique dual-indexed tag barcodes on a Bravo NGS workstation automation system (Agilent). We applied the following PCR program: 45 s at 98 °C, 14 cycles of 15 s at 98 °C, 30 s at 65 °C and 30 s at 72 °C, followed by 60 s at 72 °C. Using a Zephyr liquid handling platform (PerkinElmer), PCR products were purified using AMPure XP SPRI beads (Agencourt) at a 0.8:1 bead-to-sample ratio and then eluted in 20 μl of elution buffer (Qiagen). RNA-seq libraries were quantified with an AccuClear Ultra High Sensitivity dsDNA Quantitation Kit (Biotium) using a Mosquito LV liquid handling platform (SPT Labtech), Bravo automation system (Agilent) and FLUOstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech). Then, libraries were pooled up to 95-plex in equimolar amounts on a Biomek NX-8 liquid handling platform (Beckman Coulter), quantified using a High Sensitivity DNA Kit on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and then normalized to 2.8 nM before sequencing.

RNA-seq and data preprocessing

Samples were sequenced using 75 bp paired-end sequencing reads (reverse stranded) on a NovaSeq 6000 system (S4 flow cell, Xp workflow; Illumina). The sequencing data were deplexed into separate compressed reference-oriented alignment map (CRAM) files for each library in a lane. Adapters that had been hard-clipped before alignment were reinserted as soft-clipped postalignment, and duplicated fragments were marked in the CRAM files. The data preprocessing, including sequence QC and STAR alignments, was performed with the Nextflow pipeline publicly available at https://github.com/wtsi-hgi/nextflow-pipelines/blob/rna_seq_interval_5591/pipelines/rna_seq.nf, including the specific aligner parameters. We assessed the sequence data quality using FastQC (v0.11.8). Samples mismatched between RNA-seq and genotyping data within the cohort were identified using QTLtools MBV (v1.2)54. Reads were aligned to the GRCh38 human reference genome (Ensembl GTF annotation v99) using STAR (v2.7.3a)55. The STAR index was built against GRCh38 Ensembl GTF v99 using the option -jdbOverhang 75. STAR was run in a two-pass setup with standard ENCODE options to increase mapping accuracy: (1) a first alignment step of all samples was used to discover new splice junctions, (2) splice junctions of all samples from the first step were collected and merged into a single list, (3) a second step realigned all samples using the merged splice junctions list as input. We used featureCounts (v2.0.0)56 to obtain a count matrix.

QC of gene expression data

Sequencing was performed across 15 batches. We filtered samples of poor quality by removing samples with a read depth below 10 million uniquely mapped reads. On average, each sample had 25.3 million unique reads (interquartile range = 21.5–26.9, including batches 1 and 15 for which libraries were sequenced twice). A relatedness matrix was obtained using the PLINK (v1.9)57 -make-rel ‘square’ command on pruned genotype data, and a cutoff threshold of 0.1 was used to define related individuals. For each pair of related individuals, one individual was arbitrarily removed. After QC, a total of n = 46 samples were removed. After the sample QC, we filtered lowly expressed genes by retaining genes with >0.5 counts per million (CPM) in ≥1% of the samples, in line with the filter applied by the eQTLGen consortium9. In our dataset, a CPM value of 0.5 roughly equates to having 5 counts in a sample with the lowest read depth (10 million uniquely mapped reads) or 47 counts in a sample with the highest read depth (94 million reads). We further excluded globin genes, rRNA genes and pseudogenes. After QC, the final gene expression dataset included 19,173 autosomal genes (13,874 of which are protein-coding) across a total of 4,732 individuals.

Normalization of gene expression data

Before the eQTL analysis, the count data were normalized using the trimmed mean of M values (TMM)58 implemented in the R package edgeR (v3.24.3). The TMM-normalized values were further converted into fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values (log2-transformed) to take gene length into account. Next, for each gene, the normalized log2-FPKM values across samples were transformed via the ranked-based inverse normal transformation function ‘rntransform’ implemented in the R package GenABEL (v1.8-0)59. Inverse normal transformation was applied to ensure the expression values followed a normal distribution.

Splicing data generation

Splice junctions were extracted from aligned RNA-seq BAMs for the 4,732 individuals using Regtools (v0.5.2)60 junctions extract (parameters: ‘-s 1 -m 50’). Introns represented by extracted splice junctions were then clustered into groups based on overlapping start or end sites, with the Leafcutter pipeline (v0.2.9)52 (leafcutter_cluster_regtools.py, parameters: ‘-m 100 -M 50 -l 100000 -p 0.01’). Clustered introns were then prepared for sQTL analysis with Leafcutter prepare_phenotype_table.py to convert intron counts to normalized ratios and compute ten splicing principal components (PCs). Introns were matched to regions of Ensembl v99 genes and protein domains annotated with R v4.0.3 using a custom pipeline (described in Data availability). Total observed introns (n = 956,722) were filtered to those that were autosomal, overlapping an expressed gene body, with CPM > 0.5 in at least 24 individuals, and sufficient variance (minimum two filtered splice event phenotypes per cluster), resulting in 111,937 filtered splicing event phenotypes, in 11,016 genes (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for a summary of splicing event QC).

DNA extraction, genotyping and imputation

In brief, DNA extracted from buffy coat samples collected from INTERVAL participants at the study baseline was used to assay approximately 830,000 variants on the Affymetrix Axiom UK Biobank genotyping array61. Genotyping and sample QC were performed as previously described61. Before imputation, additional variant filtering steps were performed to establish a high-quality imputation scaffold, including 654,966 autosomal, nonmonomorphic, bi-allelic variants with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P > 5 × 10−6, with a call rate of >99% across the INTERVAL genotyping batches in which a variant passed QC and a global call rate of >75% across all INTERVAL genotyping batches. Next, variants were phased using SHAPEIT3 and imputed using a combined 1000 Genomes Phase 3-UK10K reference panel. Imputation was performed via the Sanger Imputation Server (https://imputation.sanger.ac.uk) and resulted in 87,696,888 imputed variants. For the present analysis, imputed genotypes were lifted over to reference build GRCh38 using CrossMap (v0.3.4)62 and the Ensembl chain file provided with the package. Imputed genotypes were hard-called with PLINK (v2.00a2-32-bit)57 using the default parameters. Before analysis, the dataset was restricted to individuals with RNA-seq and filtered to remove genetic variants with HWE exact test P < 1 × 10−6, genotype missingness >0.05 or minor allele frequency < 0.5%.

Identification of sample swaps and cross-contamination

The Match BAM to VCF (MBV) method from QTLTools54 was used to identify sample mix-ups and cross-contamination. MBV directly compares each aligned RNA-seq BAM file to all the genotypes in the VCF file and computes the proportion of concordant heterozygous and homozygous sites. To reduce computation time, we only focused on chromosome 1. Based on the concordance (close to 100%) between the genotype data and RNA-seq samples, we identified and corrected ten pairs of mislabeled samples. We removed seven RNA-seq samples that did not show a clear high concordance (the highest was <50%) with any particular genotype sample—either due to cross-contamination or the actual matching genotypes were not available.

PEER factor and splicing PC analysis

We used the probabilistic estimation of expression residuals (PEER) method63, implemented in the R package peer v.1.0 (downloaded from https://github.com/PMBio/peer), to detect and correct eQTL mapping for latent batch effects and other unknown confounders. PEER factors were estimated while accounting for age, sex, body mass index and 19 blood cell traits (Supplementary Table 28) as known confounders. PEER was run for 50 factors, converging at 148 iterations. For inclusion in the eQTL analysis, we selected the number of PEER factors based on the following two criteria: (1) discovery of the largest number of cis-eGenes and (2) additional gain in cis-eGenes with incremental increase in PEER factors (Supplementary Fig. 9a). We found that the relationship between the increase in the number of discovered cis-eGenes and the incremental increase in PEER factors is similar to that observed in the GTEx whole-blood dataset22. Therefore, we included 35 PEER factors in our eQTL analysis, consistent with GTEx. We used a similar approach to determine the optimal number of PCs to include in the sQTL analysis, testing 0–10 PCs. We found that cis-sQTL discovery only increased slightly with the number of PCs included with no obvious threshold (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Given that ten PCs were established as a previous default for sQTL mapping52, we opted to include ten splicing PCs.

Mapping of eQTLs and sQTLs

eQTLs and splicing QTLs were called using tensorQTL (v1.0.6)64 and postprocessed with a custom pipeline65. The covariates integrated into the regression model are listed and described in Supplementary Tables 27 and 28. In brief, these included (1) demographic variables such as age at blood sampling, sex and body mass index at baseline (because it was not collected at the time of blood sampling), (2) technical variables such as RIN, read depth and season of blood sampling, (3) ten genotype PCs and 35 PEER factors (for eQTLs) or ten splicing PCs (for sQTLs) and (4) 19 different blood cell traits. For the cis-eQTL analysis, variants were defined as being in cis with a gene if they were located within a window of ±1 Mb from the TSS. For the sQTL analysis, the window was set to ±500 kb from the center of the splicing event to balance primary and secondary sQTL discovery. Feature annotation, including TSS position, was obtained from Ensembl v99 (January 2020). For both cis-eQTL and cis-sQTL analyses, multiple-testing correction was applied in tensorQTL as follows: (1) for each gene (or splicing event), the adjusted lowest P value was estimated using a β distribution approximation from a permutation procedure (10,000 permutations)66; (2) Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction was applied to the β-approximated P values across genes (or splicing events), and the FDR q value threshold was set to 5%. For each significant gene (or splicing event), a nominal P-value threshold was estimated to identify significant SNPs. To demonstrate how increased sample size assists in cis-eQTL and cis-sQTL discovery, random samples of patients in n = 500 increments were subsetted and QTL mapping was performed with the same inputs as the full cis-QTL analyses, with the output being the number of significant genes (or splice phenotypes) with a significant eQTL (or sQTL). Conditional analysis was performed for each cis-eGene (or splicing event phenotype with a cis-sQTL) using GCTA-COJO v1.94.0beta (January 2022)67,68. The program took as input the gene cis-eQTL (or cis-sQTL) summary statistics, the INTERVAL imputed genotype data for cis-variants and the P-value threshold used to identify the cis-eGene (or splicing QTL). A trans-eQTL analysis was performed on the list of lead SNPs from cis-eGenes independent signals. The trans-regions were defined as genomic regions outside of the ±5 Mb window from the TSS. The Bonferroni multiple-testing correction method (that is, P = 0.05/number of tested trans-associations) was applied to identify significant trans-associations. While previous work has demonstrated that trans-QTL analyses may be susceptible to artifacts due to read cross-mapping between similar genes69, our quantification approach using only uniquely mapped reads led to only a small fraction of our trans-QTL results (that is, 12.2% of trans-eQTLs and 23.6% of trans-sQTLs) involving genes that were flagged for sequence similarity. For the trans-QTL analyses, we also assessed if there were PEER factors or splicing PCs associated with cis-eSNPs. We did not detect any significant associations (P < 9.4 × 10−8, Bonferroni multiple-testing correction across 53,457 cis-eSNPs and ten splicing PCs) between cis-eSNPs and splicing PCs. However, we found that ten cis-eSNPs were significantly associated with five PEER factors (P < 2.7 × 10−8, Bonferroni multiple-testing correction across 53,457 cis-eSNPs and 35 PEER factors). As a sensitivity analysis, we performed the trans-eQTL analyses with and without these five PEER factors. We showed a high correlation of z scores for trans-eQTL involving these ten SNPs before and after removing these PEER factors from the model (Pearson correlation = 0.80; Supplementary Fig. 10). We identified significant associations of cis-eSNPs with an additional 121 trans-eGenes. Overall, we identified a higher number of trans-eGenes by integrating all 35 PEER factors in the model (that is, 2,058 trans-eGenes instead of 1,811 trans-eGenes).

Validation of cis-eQTL and cis-sQTL results

Results from the cis-eQTL analysis were compared to the results obtained in the eQTLGen study9, which are available at https://www.eqtlgen.org/cis-eqtls.html. In our comparison, we explored the percentage of overlap of cis-eGenes and the effect direction of genetic associations. For the overlap of cis-eGenes, we focused on the list of 15,722 genes that were tested in both INTERVAL and eQTLGen. For the comparison of effect directions, we computed the correlation of z scores for SNPs that were the most significant in INTERVAL for each gene and that were also tested in eQTLGen. Results from sQTL analysis were collapsed to the sGene level for comparison to GTEx whole-blood sQTLs (v.8)22, which are available at https://gtexportal.org/home/datasets.

Enrichment analyses

Enrichment analyses were performed using a one-sided Fisher’s exact test on QTL results annotated with GO terms70 (downloaded in May 2022) and the Human Transcription Factors database23. We tested for enrichment within cis-eGenes with a trans-association with gene expression or splicing using significant cis-eGenes as background. Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction was applied to identify significant enrichment.

Colocalization analysis

Colocalization analysis was performed using the results of conditional analysis from GCTA-COJO67,68 and the R package Coloc (v5.1.0.1)71 on pairwise independent QTL signals following the pwCoCo methodology72. The colocalization analysis window was the entire cis-window, that is, ±1 Mb for eQTLs and ±500 kb for sQTLs. Prior probabilities were kept as the default values, that is, P1 = 1 × 10−4, P2 = 1 × 10−4 and P12 = 1 × 10−5. Colocalized results were defined with the thresholds PP3 + PP4 ≥ 0.9 and PP4/PP3 ≥ 3, PP3 and PP4 being the posterior probabilities of hypotheses 3 and 4 as outlined previously71. For colocalization analysis with external omics data, summary statistics were downloaded from each study (see Supplementary Table 29 for the description of the different omics studies). A previous study performed simulations showing that the impact of complete sample overlap on colocalization results was negligible with 200 individuals and, therefore, will be even smaller with large sample sizes as used here73. Before colocalization analysis, (1) proteins were annotated using the R package biomaRt (v2.46.3) to obtain corresponding genes in Ensembl v99 (January 2020), and (2) significant pQTLs and mQTL were filtered. For pQTLs, P-value thresholds per feature were defined by a two-step multiple-testing correction74,75. For mQTLs, we used a Bonferroni-adjusted P-value threshold of P < 5 × 10−8, corrected for the number of metabolites analyzed.

Mediation analysis

Mediation analyses were conducted using the natural effects model implemented in the R package Medflex (v0.6-7)76. In the models, we defined (1) the independent lead cis-eQTL (or cis-sQTL) SNP (coded as 0, 1 and 2) as the independent (exposure) variable, (2) the gene expression level (or splicing event phenotype) of the cis-eGene/-sGene as the mediator and (3) the molecular trait as the dependent (outcome) variable. Gene expression (or splicing event phenotype) residuals were computed after adjusting for the same covariates as we used for eQTL/sQTL mapping, while molecular traits were adjusted for covariates described by each study (Supplementary Table 29). For all mediation analyses, samples with missing genotype or molecular data were removed. Standard errors were computed based on the robust sandwich estimator. Significant direct, indirect and total effects were identified after Bonferroni multiple-testing correction between each molecular phenotype assay.

Interactive QTL web portal

To facilitate the accessibility of the results, a web portal was built to enable the exploration of eQTL and sQTLs. Summary statistics and expression phenotypes were imported into a MariaDB (v10.2.38) database; code was written to facilitate their retrieval in PHP (v7.2.34) with jQuery (v3.5.1) and styled with Bootstrap (v3.4.1). Tables are powered by DataTables (v1.13.3). Locus and QTL plots are visualized with LocusZoomJS (v0.13.4) and plotly (v2.9.0), respectively.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses, except due to the QC steps detailed above. The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The INTERVAL study data used in this paper are available to bona fide researchers from ceu-dataaccess@medschl.cam.ac.uk. The data access policy for the data has been approved by the ethics committee and is available at https://www.donorhealth-btru.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Data-Access-Policy-v1.0-14Apr2020.pdf. The release of data is regulated by the Blood Donors Studies BioResource Data Access Committee (DAC). The DAC will review the project’s scientific excellence and alignment of the proposal with the overall aims of the database; the research team’s experience and capability to conduct the proposed study; and the suitability of the data and any risk to participant confidentiality. The data access process takes approximately 2 months. The newly generated RNA-seq data (n = 4,732 INTERVAL participants) have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive under the accession EGAD00001008015. The results from the genetic association, colocalization and mediation analyses are available at https://IntervalRNA.org.uk. The summary statistics are also made available on the above web portal, as well as mirrored on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.25.23299014)77. Our data used annotation from Ensembl (https://www.ensembl.org/). For enrichment analyses, we used the public databases GO (https://geneontology.org/)70 and The Human Transcription Factors (https://humantfs.ccbr.utoronto.ca/)23.

Code availability

All original code has been deposited on GitHub (https://github.com/INTERVAL-RNAseq/manuscript-scripts) and a static version archived on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14015194)65.

References

Loos, R. J. F. 15 years of genome-wide association studies and no signs of slowing down. Nat. Commun. 11, 5900 (2020).

Albert, F. W. & Kruglyak, L. The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 197–212 (2015).

Neumeyer, S., Hemani, G. & Zeggini, E. Strengthening causal inference for complex disease using molecular quantitative trait loci. Trends Mol. Med. 26, 232–241 (2020).

Suhre, K. et al. Human metabolic individuality in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. Nature 477, 54–60 (2011).

Sun, B. B. et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 558, 73–79 (2018).

Suhre, K., McCarthy, M. I. & Schwenk, J. M. Genetics meets proteomics: perspectives for large population-based studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 19–37 (2021).

Kim-Hellmuth, S. et al. Cell type-specific genetic regulation of gene expression across human tissues. Science 369, eaaz8528 (2020).

Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1712–1721 (2021).

Vosa, U. et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 1300–1310 (2021).

Surendran, P. et al. Rare and common genetic determinants of metabolic individuality and their effects on human health. Nat. Med. 28, 2321–2332 (2022).

Julkunen, H. et al. Atlas of plasma NMR biomarkers for health and disease in 118,461 individuals from the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 14, 604 (2023).

Sun, B. B. et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 329–338 (2023).

Suhre, K. et al. Connecting genetic risk to disease end points through the human blood plasma proteome. Nat. Commun. 8, 14357 (2017).

Burgess, S. et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations: update for summer 2023. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 186 (2019).

Moore, C. et al. The INTERVAL trial to determine whether intervals between blood donations can be safely and acceptably decreased to optimise blood supply: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 15, 363 (2014).

Di Angelantonio, E. et al. Efficiency and safety of varying the frequency of whole blood donation (INTERVAL): a randomised trial of 45 000 donors. Lancet 390, 2360–2371 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. Systematic Mendelian randomization using the human plasma proteome to discover potential therapeutic targets for stroke. Nat. Commun. 13, 6143 (2022).

Zhao, J. H. et al. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune-mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 24, 1540–1551 (2023).

Riveros-Mckay, F. et al. The influence of rare variants in circulating metabolic biomarkers. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008605 (2020).

Karjalainen, M. K. et al. Genome-wide characterization of circulating metabolic biomarkers. Nature 628, 130–138 (2024).

Yamaguchi, K. et al. Splicing QTL analysis focusing on coding sequences reveals mechanisms for disease susceptibility loci. Nat. Commun. 13, 4659 (2022).

GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Lambert, S. A. et al. The human transcription factors. Cell 172, 650–665 (2018).

Keyvani Chahi, A. et al. PLAG1 dampens protein synthesis to promote human hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Blood 140, 992–1008 (2022).

Pietzner, M. et al. Mapping the proteo-genomic convergence of human diseases. Science 374, eabj1541 (2021).

Eldjarn, G. H. et al. Large-scale plasma proteomics comparisons through genetics and disease associations. Nature 622, 348–358 (2023).

Xing, Y., Xu, Q. & Lee, C. Widespread production of novel soluble protein isoforms by alternative splicing removal of transmembrane anchoring domains. FEBS Lett. 555, 572–578 (2003).

Paronetto, M. P., Passacantilli, I. & Sette, C. Alternative splicing and cell survival: from tissue homeostasis to disease. Cell Death Differ. 23, 1919–1929 (2016).

Goodwin, R. G. et al. Cloning of the human and murine interleukin-7 receptors: demonstration of a soluble form and homology to a new receptor superfamily. Cell 60, 941–951 (1990).

Lust, J. A. et al. Isolation of an mRNA encoding a soluble form of the human interleukin-6 receptor. Cytokine 4, 96–100 (1992).

Briso, E. M., Dienz, O. & Rincon, M. Cutting edge: soluble IL-6R is produced by IL-6R ectodomain shedding in activated CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 180, 7102–7106 (2008).

Garbers, C. et al. The interleukin-6 receptor Asp358Ala single nucleotide polymorphism rs2228145 confers increased proteolytic conversion rates by ADAM proteases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 1485–1494 (2014).

Hormozdiari, F. et al. Colocalization of GWAS and eQTL signals detects target genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 1245–1260 (2016).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518 (2023).

Akbari, P. et al. A genome-wide association study of blood cell morphology identifies cellular proteins implicated in disease aetiology. Nat. Commun. 14, 5023 (2023).

Gregory, S. G. et al. Interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) shows allelic and functional association with multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 39, 1083–1091 (2007).

Ahn, Y. H. et al. Secreted tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase as a primary defence system against infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16191 (2016).

Gioelli, N. et al. Neuropilin 1 and its inhibitory ligand mini-tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase inversely regulate VE-cadherin turnover and vascular permeability. Nat. Commun. 13, 4188 (2022).

COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. A first update on mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 608, E1–E10 (2022).

Bonnevie-Nielsen, V. et al. Variation in antiviral 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (2'5’AS) enzyme activity is controlled by a single-nucleotide polymorphism at a splice-acceptor site in the OAS1 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 623–633 (2005).

Huffman, J. E. et al. Multi-ancestry fine mapping implicates OAS1 splicing in risk of severe COVID-19. Nat. Genet. 54, 125–127 (2022).

Smieszek, S. P., Polymeropoulos, V. M., Xiao, C., Polymeropoulos, C. M. & Polymeropoulos, M. H. Loss-of-function mutations in IFNAR2 in COVID-19 severe infection susceptibility. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 26, 239–240 (2021).

Novick, D., Cohen, B., Tal, N. & Rubinstein, M. Soluble and membrane-anchored forms of the human IFN-α/β receptor. J. Leukoc. Biol. 57, 712–718 (1995).

Yaugel-Novoa, M., Bourlet, T., Longet, S., Botelho-Nevers, E. & Paul, S. Association of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 with COVID-19 severity. Lancet Microbe 4, e487 (2023).

Finucane, H. K. et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 47, 1228–1235 (2015).

Li, Y. I. et al. RNA splicing is a primary link between genetic variation and disease. Science 352, 600–604 (2016).

Ritchie, S. C. et al. Quality control and removal of technical variation of NMR metabolic biomarker data in ~120,000 UK Biobank participants. Sci. Data 10, 64 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Functional architectures of local and distal regulation of gene expression in multiple human tissues. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 605–616 (2017).

Qi, T. et al. Identifying gene targets for brain-related traits using transcriptomic and methylomic data from blood. Nat. Commun. 9, 2282 (2018).

Van der Wijst, M. et al. The single-cell eQTLGen consortium. eLife 9, e52155 (2020).

Cuomo, A. S. E., Nathan, A., Raychaudhuri, S., MacArthur, D. G. & Powell, J. E. Single-cell genomics meets human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 24, 535–549 (2023).

Li, Y. I. et al. Annotation-free quantification of RNA splicing using LeafCutter. Nat. Genet. 50, 151–158 (2018).

Mostafavi, H., Spence, J. P., Naqvi, S. & Pritchard, J. K. Systematic differences in discovery of genetic effects on gene expression and complex traits. Nat. Genet. 55, 1866–1875 (2023).

Fort, A. et al. MBV: a method to solve sample mislabeling and detect technical bias in large combined genotype and sequencing assay datasets. Bioinformatics 33, 1895–1897 (2017).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7 (2015).

Robinson, M. D. & Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 11, R25 (2010).

Aulchenko, Y. S., Ripke, S., Isaacs, A. & van Duijn, C. M. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23, 1294–1296 (2007).

Cotto, K. C. et al. Integrated analysis of genomic and transcriptomic data for the discovery of splice-associated variants in cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 1589 (2023).

Astle, W. J. et al. The allelic landscape of human blood cell trait variation and links to common complex disease. Cell 167, 1415–1429 (2016).

Zhao, H. et al. CrossMap: a versatile tool for coordinate conversion between genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 30, 1006–1007 (2014).

Stegle, O., Parts, L., Piipari, M., Winn, J. & Durbin, R. Using probabilistic estimation of expression residuals (PEER) to obtain increased power and interpretability of gene expression analyses. Nat. Protoc. 7, 500–507 (2012).

Taylor-Weiner, A. et al. Scaling computational genomics to millions of individuals with GPUs. Genome Biol. 20, 228 (2019).

Persyn, E. & Tokolyi, A. INTERVAL-RNAseq manuscript-scripts v1.0.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14015194 (2024).

Ongen, H., Buil, A., Brown, A. A., Dermitzakis, E. T. & Delaneau, O. Fast and efficient QTL mapper for thousands of molecular phenotypes. Bioinformatics 32, 1479–1485 (2016).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Yang, J. et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat. Genet. 44, 369–375 (2012).

Saha, A. & Battle, A. False positives in trans-eQTL and co-expression analyses arising from RNA-sequencing alignment errors. F1000Res 7, 1860 (2018).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000).

Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004383 (2014).

Zheng, J. et al. Phenome-wide Mendelian randomization mapping the influence of the plasma proteome on complex diseases. Nat. Genet. 52, 1122–1131 (2020).

Mitchelmore, J., Grinberg, N. F., Wallace, C. & Spivakov, M. Functional effects of variation in transcription factor binding highlight long-range gene regulation by epromoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 2866–2879 (2020).

Peterson, C. B., Bogomolov, M., Benjamini, Y. & Sabatti, C. TreeQTL: hierarchical error control for eQTL findings. Bioinformatics 32, 2556–2558 (2016).

Huang, Q. Q., Ritchie, S. C., Brozynska, M. & Inouye, M. Power, false discovery rate and Winner’s Curse in eQTL studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e133 (2018).

Steen, J., Loeys, T., Moerkerke, B. & Vansteelandt, S. medflex: an R package for flexible mediation analysis using natural effect models. J. Stat. Softw. 76, 1–46 (2017).

Tokolyi, A. & Persyn, E. INTERVAL eQTL & sQTL summary statistics [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.25.23299014 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Participants in the INTERVAL randomized controlled trial were recruited with the active collaboration of NHSBT England (https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/), which has supported fieldwork and other elements of the trial. DNA extraction and genotyping were cofunded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), the NIHR BioResource (https://bioresource.nihr.ac.uk/) and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). RNA-seq was funded as part of an alliance between the University of Cambridge and the AstraZeneca Centre for Genomics Research, as well as by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). Olink Target assays (Neurology panel) were funded by Biogen. SomaLogic assays were funded by Merck & Co and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). Metabolon HD4 assays were funded by the NIHR BioResource, NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014), Wellcome Trust (number 206194) and BioMarin Pharmaceutical. Nightingale Health assays were funded by the European Commission Framework Programme 7 (HEALTH-F2-2012-279233). The academic coordinating center for INTERVAL was supported by core funding from the NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit (BTRU) in Donor Health and Genomics (NIHR BTRU-2014-10024), NIHR BTRU in Donor Health and Behavior (NIHR203337), UK Medical Research Council (MR/L003120/1), British Heart Foundation (SP/09/002, RG/13/13/30194, RG/18/13/33946 and RG/F/23/110103), BHF Chair Award (CH/12/2/29428) and NIHR Cambridge BRC (BRC-1215-20014 and NIHR203312). A complete list of the investigators and contributors to the INTERVAL trial is provided in ref. 16. The academic coordinating center thanks blood donor center staff and blood donors for participating in the INTERVAL trial. This work was supported by Health Data Research UK, which is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation and Wellcome. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The Wellcome Sanger Institute is supported by core funding from the Wellcome Trust (206194 and 220540/Z/20/A). We thank the Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Scientific Operations team for their contribution to sequencing data generation. For Open Access, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. This work was performed using resources provided by the Cambridge Service for Data Driven Discovery (CSD3) operated by the University of Cambridge Research Computing Service (https://www.csd3.cam.ac.uk/), provided by Dell EMC and Intel using Tier-2 funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (capital grant EP/P020259/1), and DiRAC funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (https://dirac.ac.uk/). We thank the participants and investigators of the UK Biobank study who made this work possible (resource applications 26041 and 65851). A.T. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (PhD studentship 222548/Z/21/Z). E.P. is funded by the EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking BigData@Heart (grant 116074) and by the NIHR BTRU in Donor Health and Behavior (NIHR203337). S.C.R. is funded by a BHF Programme Grant (RG/18/13/33946) and the NIHR Cambridge BRC (BRC-1215-20014 and NIHR203312). Y.X. is supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ES/T013192/1). J.E.P. is supported by a Medical Research Foundation Fellowship (MRF-057-0003-RG-PETE-C0799). J.D. holds a British Heart Foundation Professorship and a NIHR Senior Investigator Award. M.I. is supported by the Munz Chair of Cardiovascular Prediction and Prevention and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014 and NIHR203312), and is also supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ES/T013192/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T., E.P., M.I., E.E.D. and D.S.P. conceived the study design and wrote the paper. A.T. and E.P. conducted statistical analyses. A.P.N. performed the QC of RNA-seq data. G.N. and V.I. performed the preprocessing of RNA-seq data. J.M. made substantial contributions to the QTL mapping. A.T. developed the interactive web portal. K.L.B., T.V., M.T., D.S., X.J., S.A.L., S.C.R., Y.X., J.E.P. and A.S.B. provided critical comments on the paper. B.F., M.A.Q., D.R. and S.A.J.T. performed RNA-seq experiments. B.B.S., C.D.W., H.R., S.P., D.J.G., D.J.R., E.D.A., N.S. and J.D. provided materials and data resources. K.L.B. and A.S.B. provided critical suggestions to the study design. M.I., E.E.D. and D.S.P. supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.A.Q. is on the Key Opinion Leader panel for New England Biolabs. B.B.S. and H.R. are employees and stockholders of Biogen. C.D.W. is an employee and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson. S.P. and D.S.P. are employees and stockholders of AstraZeneca. D.J.G. is an employee and stockholder of BioMarin Pharmaceutical. D.J.R. is an employee of NHSBT. J.E.P. has received hospitality and travel expenses to speak at Olink-sponsored academic meetings (none within the past 5 years). A.S.B. has received grants outside of this work from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, BioMarin and Sanofi. M.I. is a trustee of the Public Health Genomics Foundation, a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Open Targets and has a research collaboration with AstraZeneca that is unrelated to this study. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks Stephen Montgomery, Yi Xing and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10 and Note.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–29.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tokolyi, A., Persyn, E., Nath, A.P. et al. The contribution of genetic determinants of blood gene expression and splicing to molecular phenotypes and health outcomes. Nat Genet 57, 616–625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02096-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02096-3

This article is cited by

-

Metabolic reaction fluxes as amplifiers and buffers of risk alleles for coronary artery disease

Molecular Systems Biology (2025)

-

MR-link-2: pleiotropy robust cis Mendelian randomization validated in three independent reference datasets of causality

Nature Communications (2025)