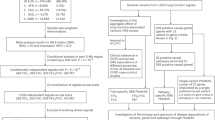

Abstract

While respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma share many risk factors, most studies investigate them in isolation and in predominantly European-ancestry populations. Here, we conducted the most powerful multi-trait and multi-ancestry genetic analysis of respiratory diseases and auxiliary traits to date, identifying 25 new loci associated with lung function in individuals of East Asian ancestry. Using these results, we developed PRSxtra (cross-trait and cross-ancestry), a multi-trait and multi-ancestry polygenic risk score (PRS) approach that leverages shared components of heritable risk via pleiotropic effects. PRSxtra significantly improved the prediction of asthma, COPD and lung cancer compared to trait- and ancestry-matched PRSs in a multi-ancestry cohort from the All of Us Research Program, especially in diverse populations. Our results present a new framework for multi-trait and multi-ancestry studies of respiratory diseases to improve genetic discovery and polygenic prediction.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The individual-level genotype and phenotype data of All of Us are available on the Researcher Workbench. Researchers can register for access at: https://www.researchallofus.org/. The GWAS summary statistics for the EAS and multi-ancestry meta-analyses of lung function are available at the GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas) under the accession codes GCST90705067, GCST90705068, GCST90705069, GCST90705070, GCST90705071 and GCST90705072. Data sources for ancestry-specific summary statistics for each trait used in this study are available in Supplementary Table 1. The weights of PRSxtra for each trait are available in Supplementary Tables 19–21.

Code availability

Analyses were conducted using publicly available software: MTAG v.2018 (https://github.com/JonJala/mtag), METAL v.2011-03-25 (https://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/METAL), PLINK v.2.0 (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/2.0/), PRS-CS v.1.1.0 (https://github.com/getian107/PRScs) and PRS-CSx v.1.1.0 (https://github.com/getian107/PRScsx). The scripts for data analyses are available at https://github.com/yixuanh/lung-mutitrait-multiancestry and at https://zenodo.org/records/17452013.

References

Chen, S. et al. The global economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and territories in 2020–50: a health-augmented macroeconomic modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 11, e1183–e1193 (2023).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Castro-Rodriguez, J. A. The Asthma Predictive Index: early diagnosis of asthma. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 11, 157–161 (2011).

He, Y. et al. Prediction and stratification of longitudinal risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease across smoking behaviors. Nat. Commun. 14, 8297 (2023).

Duffy, D. L., Martin, N. G., Battistutta, D., Hopper, J. L. & Mathews, J. D. Genetics of asthma and hay fever in Australian twins. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 142, 1351–1358 (1990).

Ingebrigtsen, T. et al. Genetic influences on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—a twin study. Respir. Med. 104, 1890–1895 (2010).

Silverman, E. K. Genetics of COPD. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 82, 413–431 (2020).

Lichtenstein, P. et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer— analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 78–85 (2000).

Karczewski, K. J. et al. Pan-UK Biobank genome-wide association analyses enhance discovery and resolution of ancestry-enriched effects. Nat. Genet. 57, 2408–2417 (2025).

Zhou, J. J. et al. Heritability of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related phenotypes in smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 941–947 (2013).

Gorman, B. R. et al. Multi-ancestry GWAS meta-analyses of lung cancer reveal susceptibility loci and elucidate smoking-independent genetic risk. Nat. Commun. 15, 8629 (2024).

Moll, M. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related phenotypes: polygenic risk scores in population-based and case-control cohorts. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 696–708 (2020).

Tsuo, K. et al. Multi-ancestry meta-analysis of asthma identifies novel associations and highlights the value of increased power and diversity. Cell Genom. 2, 100212 (2022).

Turley, P. et al. Multi-trait analysis of genome-wide association summary statistics using MTAG. Nat. Genet. 50, 229–237 (2018).

Grove, J. et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet. 51, 431–444 (2019).

Tadros, R. et al. Shared genetic pathways contribute to risk of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies with opposite directions of effect. Nat. Genet. 53, 128–134 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet. 51, 237–244 (2019).

Patel, A. P. et al. A multi-ancestry polygenic risk score improves risk prediction for coronary artery disease. Nat. Med. 29, 1793–1803 (2023).

Inouye, M. et al. Genomic risk prediction of coronary artery disease in 480,000 adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 1883–1893 (2018).

Moll, M. et al. Polygenic risk scores identify heterogeneity in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 152, 1423–1432 (2023).

Martin, A. R. et al. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet. 51, 584–591 (2019).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Bergström, A. et al. Insights into human genetic variation and population history from 929 diverse genomes. Science 367, eaay5012 (2020).

Feng, Y.-C. A. et al. Taiwan Biobank: a rich biomedical research database of the Taiwanese population. Cell Genom. 2, 100197 (2022).

Jee, Y. H. et al. Genome-wide association studies in a large Korean cohort identify quantitative trait loci for 36 traits and illuminate their genetic architectures. Nat. Commun. 16, 4935 (2025).

Jee, Y. H. et al. Cohort profile: the Korean Cancer Prevention Study-II (KCPS-II) Biobank. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 385–386f (2018).

Shrine, N. et al. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association analyses improve resolution of genes and pathways influencing lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk. Nat. Genet. 55, 410–422 (2023).

Pirinen, M. linemodels: clustering effects based on linear relationships. Bioinformatics 39, btad115 (2023).

Ge, T. et al. Development and validation of a trans-ancestry polygenic risk score for type 2 diabetes in diverse populations. Genome Med. 14, 70 (2022).

Ruan, Y. et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat. Genet. 54, 573–580 (2022).

Ge, T., Chen, C.-Y., Ni, Y., Feng, Y.-C. A. & Smoller, J. W. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat. Commun. 10, 1776 (2019).

Truong, B. et al. Integrative polygenic risk score improves the prediction accuracy of complex traits and diseases. Cell Genom. 4, 100523 (2024).

Hammad, H. & Lambrecht, B. N. The basic immunology of asthma. Cell 184, 1469–1485 (2021).

Ramalho, S. H. R. & Shah, A. M. Lung function and cardiovascular disease: a link. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 31, 93–98 (2021).

El-Azeem, I. A. A., Hamdy, G., Amin, M. & Rashad, A. Pulmonary function changes in diabetic lung. Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 62, 513–517 (2013).

Çolak, Y., Nordestgaard, B. G. & Afzal, S. Morbidity and mortality in carriers of the cystic fibrosis mutation CFTR Phe508del in the general population. Eur. Respir. J. 56, 2000558 (2020).

Pereira, S. V.-N., Ribeiro, J. D., Ribeiro, A. F., Bertuzzo, C. S. & Marson, F. A. L. Novel, rare and common pathogenic variants in the CFTR gene screened by high-throughput sequencing technology and predicted by in silico tools. Sci. Rep. 9, 6234 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Rare variants of large effect in BRCA2 and CHEK2 affect risk of lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 46, 736–741 (2014).

Cortez Cardoso Penha, R. et al. Common genetic variations in telomere length genes and lung cancer: a Mendelian randomisation study and its novel application in lung tumour transcriptome. eLife 12, e83118 (2023).

Kachuri, L. et al. Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis of leukocyte telomere length and risk of lung and head and neck cancers. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48, 751–766 (2019).

Shi, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of lung adenocarcinoma in East Asia and comparison with a European population. Nat. Commun. 14, 3043 (2023).

Duckworth, A. et al. Telomere length and risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Respir. Med. 9, 285–294 (2021).

Xu, K. et al. Genome-wide association study of smoking trajectory and meta-analysis of smoking status in 842,000 individuals. Nat. Commun. 11, 5302 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Significant associations of CHRNA2 and CHRNA6 with nicotine dependence in European American and African American populations. Hum. Genet. 133, 575–586 (2014).

Thorgeirsson, T. E. et al. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452, 638–642 (2008).

Saccone, N. L. et al. Multiple distinct risk loci for nicotine dependence identified by dense coverage of the complete family of nicotinic receptor subunit (CHRN) genes. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 150B, 453–466 (2009).

Ni, Z. et al. CLPTM1L is overexpressed in lung cancer and associated with apoptosis. PLoS ONE 7, e52598 (2012).

Chen, X. F. et al. Multiple variants of TERT and CLPTM1L constitute risk factors for lung adenocarcinoma. Genet. Mol. Res. 11, 370–378 (2012).

James, M. A., Vikis, H. G., Tate, E., Rymaszewski, A. L. & You, M. CRR9/CLPTM1L regulates cell survival signaling and is required for Ras transformation and lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 74, 1116–1127 (2014).

Ortega, V. E. et al. The effects of rare SERPINA1 variants on lung function and emphysema in SPIROMICS. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201, 540–554 (2020).

Stoller, J. K. & Aboussouan, L. S. α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Lancet 365, 2225–2236 (2005).

Brenner, D. R., McLaughlin, J. R. & Hung, R. J. Previous lung diseases and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 6, e17479 (2011).

Denholm, R. et al. Is previous respiratory disease a risk factor for lung cancer? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 549–559 (2014).

Kachuri, L. et al. Immune-mediated genetic pathways resulting in pulmonary function impairment increase lung cancer susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 11, 27 (2020).

Zhang, D. et al. Exploring the relationship between Treg-mediated risk in COPD and lung cancer through Mendelian randomization analysis and scRNA-seq data integration. BMC Cancer 24, 453 (2024).

Barr, R. G. et al. Pulmonary disease and age at immigration among Hispanics. Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193, 386–395 (2016).

Pino-Yanes, M. et al. Genetic ancestry influences asthma susceptibility and lung function among Latinos. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 228–235 (2015).

Kachuri, L. et al. Gene expression in African Americans, Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans reveals ancestry-specific patterns of genetic architecture. Nat. Genet. 55, 952–963 (2023).

Cooke, C. R. et al. The validity of using ICD-9 codes and pharmacy records to identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11, 37 (2011).

Buhr, R. G. et al. Reversible airflow obstruction predicts future chronic obstructive pulmonary disease development in the SPIROMICS cohort: an observational cohort study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206, 554–562 (2022).

Hobbs, B. D. et al. Genetic loci associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap with loci for lung function and pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 49, 426–432 (2017).

The All of Us Research Program Investigators The “All of Us” Research Program. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 668–676 (2019).

He, Y. & Martin, A. R. We need more-diverse biobanks to improve behavioural genetics. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 197–200 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Multi-trait and multi-ancestry genetic analysis of comorbid lung diseases and traits improves genetic discovery and polygenic risk prediction. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/17452013 (2024).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. K. et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291–295 (2015).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 47, 1236–1241 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Genome-wide association study of lung function and clinical implication in heavy smokers. BMC Med. Genet. 19, 134 (2018).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (T32HG010464 to Y.H., K99HG013969 to Y.W. and U01HG011719 to A.R.M.), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES032470 and R01DK137993 to C.J.P.), the National Cancer Institute (U19CA203654 and R01CA243483 to C.I.A. and J.B.), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL179112 to A.R.M. and W.L. and R01HL168199, R01HL162813, R01HL153248 and R01HL135142 to M.H.C.) and the National Institute of Mental Health (K99/R00MH117229 to A.R.M.). We are grateful to the All of Us participants for their contributions. We also thank the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us Research Program for making available the participant data examined in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H., M.M., M.H.C. and A.R.M. designed the study. Y.H., W.L., Y.H.J. and M.-Y.S. processed, analyzed and conducted statistical analysis of the data. Y.W. and K.T. provided methodological and statistical advice. Y.H.J., M.-Y.S., Y.-C.A.F., H.H., J.B. and C.I.A. contributed data. Y.H., W.L., D.C.Q., J.A.D., Y.-C.A.F., M.M., M.H.C. and A.R.M. interpreted the data. A.R.M. and Y.H. obtained funding. All authors (Y.H., W.L., Y.H.J., M.-Y.S., Y.W., K.T., D.C.Q., J.A.D., H.H., C.J.P., J.B., B.P., E.G.A., C.I.A., Y.-C.A.F., M.M., M.H.C. and A.R.M.) provided critical feedback and revisions for the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.H.C. has received grant support from GSK, consulting fees from Apogee and BMS, and speaking fees from Illumina. M.M. has received consulting fees from Thea Health, 2nd.MD, Axon Advisors, Verona Pharma and Sanofi. A.R.M. has received speaker fees from Novartis. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks Haoyu Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Frequency and effect size of risk alleles of the 13 index variants associated with FEV1.

These variants reached genome-wide significance in meta-analyzed GWAS of East Asian ancestry population (P < 5 × 10−8, derived from METAL). Dark blue shaded boxes represent variants that were present and significant (P < 5 × 10−8) in the GWAS. Light blue shaded boxes represent variants that were present but not significant. Unshaded white boxes represent variants that were not present in the GWAS.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Frequency and effect size of risk alleles of the 37 index variants associated with FVC.

These variants reached genome-wide significance in meta-analyzed GWAS of East Asian ancestry population (P < 5 × 10−8, derived from METAL). Dark blue shaded boxes represent variants that were present and significant (P < 5 × 10−8) in the GWAS. Light blue shaded boxes represent variants that were present but not significant. Unshaded white boxes represent variants that were not present in the GWAS.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Frequency and effect size of risk alleles of the 24 index variants associated with FEV1/FVC.

These variants reached genome-wide significance in meta-analyzed GWAS of East Asian ancestry population (P < 5 × 10−8, derived from METAL). Dark blue shaded boxes represent variants that were present and significant (P < 5 × 10−8) in the GWAS. Light blue shaded boxes represent variants that were present but not significant. Unshaded white boxes represent variants that were not present in the GWAS.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Multi-ancestry GWAS of FEV1.

The largest published GWAS of FEV1 to date is depicted in the Manhattan plot in red (bottom, with its signals in orange dots). Integrating EAS results in a multi-ancestry meta-analysis identified new signals, depicted in the Manhattan plot in blue (top, with potentially novel loci in triangles). Unadjusted two-sided P values derived from METAL are on a −log10 scale. Novel loci with P < 10−10 are annotated with the nearest gene.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Multi-ancestry GWAS of FVC.

The largest published GWAS of FVC to date is depicted in the Manhattan plot in red (bottom, with its signals in orange dots). Integrating EAS results in a multi-ancestry meta-analysis identified new signals, depicted in the Manhattan plot in blue (top, with potentially novel loci in triangles). Unadjusted two-sided P values derived from METAL are on a −log10 scale. Novel loci with P < 10−10 are annotated with the nearest gene.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Shared and distinct heritable components between asthma and other traits.

a–n, Comparison of effect sizes of variants from GWAS for asthma vs. five other traits (columns) across all available ancestry groups (rows) in models fitted with two lines. Effect sizes of variants on asthma are on the x-axis, and effect sizes of variants on the other traits are on the y-axis. Each point represents a variant significantly associated (P < 5 × 10−8) with at least one of the corresponding pair of traits. In a shared variants analysis, variants predominantly (with posterior probability >99%) associated with asthma are colored blue, and variants predominantly associated with the other trait are colored red. Gray variants were not confidently assigned to either trait (posterior probability < 99%). The colored shaded ellipse range indicates the 95% probability regions of the fitted bivariate effect size distributions with each class. Empty space means either the two traits do not have enough overlapped variants or GWAS results are not applicable for the corresponding ancestry group.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Shared and distinct heritable components between COPD and other traits.

a–k, Comparison of effect sizes of variants from GWAS for COPD vs. four other traits (columns) across all available ancestry groups (rows) in models fitted with two lines. Effect sizes of variants on COPD are on the x-axis, and effect sizes of variants on the other traits are on the y-axis. Each point represents a variant significantly associated (P < 5 × 10−8) with at least one of the corresponding pair of traits. In a shared variants analysis, variants predominantly (with posterior probability >99%) associated with COPD are colored blue, and variants predominantly associated with the other trait are colored red. Gray variants were not confidently assigned to either trait (posterior probability < 99%). The colored shaded ellipse range indicates the 95% probability regions of the fitted bivariate effect size distributions with each class. Empty space means either the two traits do not have enough overlapped variants or GWAS results are not applicable for the corresponding ancestry group.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Shared and distinct heritable components between lung cancer and other traits.

a–f, Comparison of effect sizes of variants from GWAS for lung cancer vs. three other traits (columns) across all available ancestry groups (rows) in models fitted with two lines. Effect sizes of variants on lung cancer are on the x-axis, and effect sizes of variants on the other traits are on the y-axis. Each point represents a variant significantly associated (P < 5 × 10−8) with at least one of the corresponding pair of traits. In a shared variants analysis, variants predominantly (with posterior probability >99%) associated with lung cancer are colored blue, and variants predominantly associated with the other trait are colored red. Gray variants were not confidently assigned to either trait (posterior probability < 99%). The colored shaded ellipse range indicates the 95% probability regions of the fitted bivariate effect size distributions with each class. Empty space means either the two traits do not have enough overlapped variants or GWAS results are not applicable for the corresponding ancestry group.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–15.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–40.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Lu, W., Jee, Y.H. et al. Multi-trait and multi-ancestry genetic analysis of comorbid lung diseases and traits improves genetic discovery and polygenic risk prediction. Nat Genet (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02470-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02470-1