Abstract

Cysteine cathepsins are a family of proteases that are relevant therapeutic targets for the treatment of different cancers and other diseases. However, no clinically approved drugs for these proteins exist, as their systemic inhibition can induce deleterious side effects. To address this problem, we developed a modular antibody-based platform for targeted drug delivery by conjugating non-natural peptide inhibitors (NNPIs) to antibodies. NNPIs were functionalized with reactive warheads for covalent inhibition, optimized with deep saturation mutagenesis and conjugated to antibodies to enable cell-type-specific delivery. Our antibody–peptide inhibitor conjugates specifically blocked the activity of cathepsins in different cancer cells, as well as osteoclasts, and showed therapeutic efficacy in vitro and in vivo. Overall, our approach allows for the rapid design of selective cathepsin inhibitors and can be generalized to inhibit a broad class of proteases in cancer and other diseases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The atomic models related to this study have been deposited to the PDB under accession codes 8PI3 and 8RND. Source data are provided with this paper.

Change history

15 August 2024

In the version of this article initially published, the top third section of Fig. 3d was missing and is now restored in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Turk, V. et al. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1824, 68–88 (2012).

Olson, O. C. & Joyce, J. A. Cysteine cathepsin proteases: regulators of cancer progression and therapeutic response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 712–729 (2015).

Vidak, E., Javoršek, U., Vizovišek, M. & Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins and their extracellular roles: shaping the microenvironment. Cells 8, 264 (2019).

Novinec, M. & Lenarčič, B. Papain-like peptidases: structure, function, and evolution. Biomol. Concepts 4, 287–308 (2013).

McClung, M. R. et al. Odanacatib for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: results of the LOFT multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and LOFT Extension study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7, 899–911 (2019).

Smyth, P., Sasiwachirangkul, J., Williams, R. & Scott, C. J.Cathepsin S (CTSS) activity in health and disease—a treasure trove of untapped clinical potential. Mol. Aspects Med. 88, 101106 (2022).

Costa, A. G., Cusano, N. E., Silva, B. C., Cremers, S. & Bilezikian, J. P. Cathepsin K: its skeletal actions and role as a therapeutic target in osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7, 447–456 (2011).

McGlinchey, R. P. & Lee, J. C. Cysteine cathepsins are essential in lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9322–9327 (2015).

Fonović, M. & Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1840, 2560–2570 (2014).

Dheilly, E. et al. Cathepsin S regulates antigen processing and T cell activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Cell 37, 674–689 (2020).

Bararia, D. et al. Cathepsin S alterations induce a tumor-promoting immune microenvironment in follicular lymphoma. Cell Rep. 31, 107522 (2020).

Rao, J. S. Molecular mechanisms of glioma invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 489–501 (2003).

Lah, T. T. & Kos, J. Cysteine proteinases in cancer progression and their clinical relevance for prognosis. Biol. Chem. 379, 125–130 (1998).

Sevenich, L. et al. Analysis of tumour- and stroma-supplied proteolytic networks reveals a brain-metastasis-promoting role for cathepsin S. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 876–888 (2014).

Gocheva, V. et al. Distinct roles for cysteine cathepsin genes in multistage tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 20, 543–556 (2006).

Gopinathan, A. et al. Cathepsin B promotes the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Gut 61, 877–884 (2012).

Shi, G. P. et al. Human cathepsin S: chromosomal localization, gene structure, and tissue distribution. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 11530–11536 (1994).

Riese, R. J. et al. Essential role for cathepsin S in MHC class II-associated invariant chain processing and peptide loading. Immunity 4, 357–366 (1996).

Victor, B. C., Anbalagan, A., Mohamed, M. M., Sloane, B. F. & Cavallo-Medved, D. Inhibition of cathepsin B activity attenuates extracellular matrix degradation and inflammatory breast cancer invasion. Breast Cancer Res. 13, R115 (2011).

Heidtmann, H.-H., Salge, U., Abrahamson, M., Ben, M. & Kastelic, L.Cathepsin B and cysteine proteinase inhibitors in human lung cancer cell lines. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 15, 368–381 (1997).

Niedergethmann, M. et al. Prognostic impact of cysteine proteases cathepsin B and cathepsin L in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 29, 204–211 (2004).

Nouh, M. A. et al. Cathepsin B: a potential prognostic marker for inflammatory breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 9, 1 (2011).

Fujise, N. et al. Prognostic impact of cathepsin B and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in pulmonary adenocarcinomas by immunohistochemical study. Lung Cancer 27, 19–26 (2000).

Sudhan, D. R., Pampo, C., Rice, L. & Siemann, D. W. Cathepsin L inactivation leads to multimodal inhibition of prostate cancer cell dissemination in a preclinical bone metastasis model. Int. J. Cancer 138, 2665–2677 (2016).

Le Gall, C. et al. A cathepsin K inhibitor reduces breast cancer induced osteolysis and skeletal tumor burden. Cancer Res. 67, 9894–9902 (2007).

Podgorski, I., Linebaugh, B. E. & Sloane, B. F. Cathepsin K in the bone microenvironment: link between obesity and prostate cancer? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 701–703 (2007).

Choe, Y. et al. Substrate profiling of cysteine proteases using a combinatorial peptide library identifies functionally unique specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12824–12832 (2006).

Biniossek, M. L., Nägler, D. K., Becker-Pauly, C. & Schilling, O. Proteomic identification of protease cleavage sites characterizes prime and non-prime specificity of cysteine cathepsins B, L, and S. J. Proteome Res. 10, 5363–5373 (2011).

Baugh, M. et al. Therapeutic dosing of an orally active, selective cathepsin S inhibitor suppresses disease in models of autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 36, 201–209 (2011).

Saegusa, K. et al. Cathepsin S inhibitor prevents autoantigen presentation and autoimmunity. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 361–369 (2002).

Lee-Dutra, A., Wiener, D. K. & Sun, S. Cathepsin S inhibitors: 2004–2010. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 21, 311–337 (2011).

Theron, M. et al. Pharmacodynamic monitoring of RO5459072, a small molecule inhibitor of cathepsin S. Front. Immunol. 8, 806 (2017).

Payne, C. D. et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the cathepsin S inhibitor, LY3000328, in healthy subjects: PK/PD and safety and tolerability of cathepsin S inhibitor. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 78, 1334–1342 (2014).

Kramer, L., Turk, D. & Turk, B. The future of cysteine cathepsins in disease management. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 873–898 (2017).

Gauthier, J. Y. et al. The discovery of odanacatib (MK-0822), a selective inhibitor of cathepsin K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 923–928 (2008).

Stoch, S. A. et al. Effect of the cathepsin K inhibitor odanacatib on bone resorption biomarkers in healthy postmenopausal women: two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase I studies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 86, 175–182 (2009).

Bone, H. G. et al. Odanacatib, a cathepsin-K inhibitor for osteoporosis: a two-year study in postmenopausal women with low bone density. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 937–947 (2010).

Lindström, E. et al. Nonclinical and clinical pharmacological characterization of the potent and selective cathepsin K inhibitor MIV-711. J. Transl. Med. 16, 125 (2018).

Hargreaves, P. et al. Differential effects of specific cathepsin S inhibition in biocompartments from patients with primary Sjögren syndrome. Arthritis Res. Ther. 21, 175 (2019).

Chen, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of odanacatib for osteoporosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Osteoporos. 18, 67 (2023).

Bentley, D., Fisher, B. A., Barone, F., Kolb, F. A. & Attley, G.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study on the effects of a cathepsin S inhibitor in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 62, 3644–3653 (2023).

Mullard, A. Merck & Co. drops osteoporosis drug odanacatib. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 669–669 (2016).

Van Dalen, F. J. et al. Application of a highly selective cathepsin S two-step activity-based probe in multicolor bio-orthogonal correlative light-electron microscopy. Front. Chem. 8, 628433 (2021).

Bratkovič, T. et al. Affinity selection to papain yields potent peptide inhibitors of cathepsins L, B, H, and K. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 332, 897–903 (2005).

Gobec, S. & Frlan, R. Inhibitors of cathepsin B. Curr. Med. Chem. 13, 2309–2327 (2006).

Hamilton, G. S. Antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy: the technological and regulatory challenges of developing drug–biologic hybrids. Biologicals 43, 318–332 (2015).

Mullard, A. Maturing antibody–drug conjugate pipeline hits 30. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 329–332 (2013).

Flygare, J. A., Pillow, T. H. & Aristoff, P. Antibody–drug conjugates for the treatment of cancer. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 81, 113–121 (2013).

Chalouni, C. & Doll, S. Fate of antibody–drug conjugates in cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37, 20 (2018).

Pauly, T. A. et al. Specificity determinants of human cathepsin S revealed by crystal structures of complexes. Biochemistry 42, 3203–3213 (2003).

Zoete, V. et al. Attracting cavities for docking. Replacing the rough energy landscape of the protein by a smooth attracting landscape. J. Comput. Chem. 37, 437–447 (2016).

Gaieb, Z. et al. D3R Grand Challenge 3: blind prediction of protein–ligand poses and affinity rankings. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 33, 1–18 (2019).

Craik, D. J., Fairlie, D. P., Liras, S. & Price, D. The future of peptide-based drugs: peptides in drug development. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 81, 136–147 (2013).

Diao, L. & Meibohm, B. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic correlations of therapeutic peptides. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 52, 855–868 (2013).

Fosgerau, K. & Hoffmann, T. Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discov. Today 20, 122–128 (2015).

Verdoes, M. et al. Improved quenched fluorescent probe for imaging of cysteine cathepsin activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14726–14730 (2013).

Edgington-Mitchell, L. E., Bogyo, M. & Verdoes, M. in Activity-Based Proteomics (eds Overkleeft, H. S. & Florea, B. I.) vol. 1491 145–159 (Springer, 2017).

Segal, E. et al. Detection of intestinal cancer by local, topical application of a quenched fluorescence probe for cysteine cathepsins. Chem. Biol. 22, 148–158 (2015).

Barrett, A. J., Kembhavi, A. A. & Hanada, K.E-64 [l-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucyl-amido(4-guanidino)butane] and related epoxides as inhibitors of cysteine proteinases. Acta Biol. Med. Ger. 40, 1513–1517 (1981).

Woo, J. T. et al. Suppressive effect of N-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-l-phenylalanyl-l-tyrosinal on bone resorption in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 300, 131–135 (1996).

Belkhiri, A. et al. Expression of t-DARPP mediates trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4564–4571 (2008).

Egle, A., Harris, A. W., Bath, M. L., O’Reilly, L. & Cory, S. VavP-Bcl2 transgenic mice develop follicular lymphoma preceded by germinal center hyperplasia. Blood 103, 2276–2283 (2004).

Boike, L., Henning, N. J. & Nomura, D. K. Advances in covalent drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 881–898 (2022).

Narayanan, A., Toner, S. A. & Jose, J. Structure-based inhibitor design and repurposing clinical drugs to target SARS-CoV-2 proteases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 50, 151–165 (2022).

López-Otín, C. & Bond, J. S. Proteases: multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30433–30437 (2008).

Young, G. et al. Quantitative mass imaging of single biological macromolecules. Science 360, 423–427 (2018).

England, R. M., Moss, J. I., Gunnarsson, A., Parker, J. S. & Ashford, M. B. Synthesis and characterization of dendrimer-based polysarcosine star polymers: well-defined, versatile platforms designed for drug-delivery applications. Biomacromolecules 21, 3332–3341 (2020).

Bertosin, E. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy and mass analysis of oligolysine-coated DNA nanostructures. ACS Nano 15, 9391–9403 (2021).

Naftaly, A., Izgilov, R., Omari, E. & Benayahu, D. Revealing advanced glycation end products associated structural changes in serum albumin. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 3179–3189 (2021).

Garrone, P. et al. Fas ligation induces apoptosis of CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 182, 1265–1273 (1995).

Delage, J. A. et al. Copper-64-labeled 1C1m-Fc, a new tool for TEM-1 PET imaging and prediction of lutetium-177-labeled 1C1m-Fc therapy efficacy and safety. Cancers 13, 5936 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the EPFL and University of Lausanne (UNIL) facilities, particularly the Protein Production and Structure Core Facility, the Biomolecular Screening Facility, the Institute of Chemical Sciences and Engineering (ISIC) Mass Spectrometry Facility and the FC Core Facility of EPFL. We also thank M. Santin, A. Buu-Hoang, E. Simkova, A. Pellegrino and G. Dienes from EPFL for their technical support with in vitro assay optimization. This work was supported by the SNF (Spark grant CRSK-3_190639, to E.O.), Leenaards Foundation (to E.O., B.E.C. and C.A.), Swiss Cancer League (KFS-5000-02-2020, to E.O.) and Fondation Aclon (to E.O.). We thank ARRONAX (Saint Herblain, France) for [64Cu] production. We thank Creoptix (Wädenswil, Switzerland) and A. Moretti for support with the Creoptix WAVE system.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P., B.E.C. and E.O. conceptualized the study. A.P. performed all the biochemical and cellular assays and animal experiments. A.P. analyzed and plotted the data. M.B., A.S.-M. and N.K. contributed to the animal experiments. L.R. contributed to non-natural peptide synthesis. S.W. and S.G. helped with antibody cloning and protein production and purification. D.I. contributed to experiments with primary cells. F.J.v.D. performed the synthesis of the qABP. D.V. performed the radiolabeling and biodistribution studies and related data analysis, with help from A.P. K.L. contributed to protein production, purification and crystallography experiments, as well as related data analysis, with help from F.P. V.Z. performed the molecular docking analysis and plotted the corresponding data. E.O., B.E.C., C.A., M.V., M.S. and F.P. supervised the different aspects of the study. E.O., A.P. and B.E.C. wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

EPFL has filed two provisional patent applications that incorporate the findings presented in this Article. E.O., A.P. and B.E.C. are named as coinventors on the first patent (European Patent Office, PCT International Application Number РСТ/EP2022/073211). E.O. and A.P. are also named as coinventors on the second patent (European Patent Office, Application Number EP24157666.9). The two patent applications cover the structure of the cathepsin inhibitors described in this study. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Anthony Rullo and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

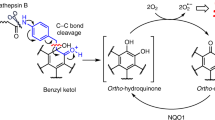

Extended Data Fig. 1 Design and development of NNPIs targeting CTSS or CTSB.

a) FRET assay assessing cleavage of 3 different substrate peptides by CTSS (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). b) Binding mode of the CD74 peptide LRMKLPKP calculated using the Attracting Cavities docking software. In the top panel, the CTSS surface is displayed and colored in brown. The peptide is shown in ball and stick representation. The central KL residues of the CD74 peptide are calculated to be in the vicinity of the CTSS Cys139 catalytic residue, labeled in bold (bottom). c) Results of FRET assay testing CTSS inhibition by NNPI-1, 2, 3 and 4 (n = 2 independent replicates). d) FRET assay assessing CTSS inhibition at increasing NNPI-3 concentrations (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). e) Sequence and CTSS inhibition capacity of different NNPIs with single amino acid substitutions compared to NNPI-3 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). f) Sequence and CTSS inhibition capacity of different NNPIs combining 2 amino acid substitutions compared to NNPI-3 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). The most potent NNPIs are labeled in blue. g) FRET dose-response quantification of CTSS inhibition by NNPI-C2 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). h) Sequence and CTSS inhibition capacity of different NNPIs combining up to 2 new amino acid substitutions compared to NNPI-C2 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). The most potent NNPI is labeled in red, and its molecular structure is represented on the right. i) Sequence and CTSB inhibition capacity of different NNPIs with up to 3 amino acid substitutions compared to NNPI-C10 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). The most potent NNPI is labeled in red, and its molecular structure is represented on the right.

Extended Data Fig. 2 NNPIs specificity and activity on CTSS Y132D.

a) IC50 values illustrating potency and specificity of NNPI-C10, D5, F17 and G14 based on FRET assays performed on a panel of 7 different cysteine cathepsin proteases (n = 3 for each condition in each FRET assay). IC50 values are given as a ratio of drug/enzyme molar concentration in the assay. b) Dose-response curve quantifying the inhibitory potency of NNPI-C10 on CTSS Y132D (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). c) Site saturation mutagenesis screening differential results comparing inhibitors on CTSS WT and CTSS Y132D. Amino acid changes colored in green favor inhibition of the mutant form over the wild-type one, whereas the orange ones work better on the wild-type form and less on the mutant CTSS (n = 2 independent replicates). d) FRET assay assessing CTSK inhibition at increasing NNPI-D1 concentrations (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). e) Sequence and CTSK inhibition capacity of different NNPIs with single amino acid substitutions compared to NNPI-D1 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). The most potent NNPI is labeled in red. f) FRET assay assessing CTSK inhibition by NNPI-D1 and NNPI-E15 at 50 nM (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown).

Extended Data Fig. 3 NNPI mutagenesis screening libraries and structural changes to obtain potent CTSK and CTSL inhibitors.

a, b) Single-site mutagenesis screening libraries applied to CTSS and CTSB (a) or CTSK and CTSL (b). c, d) Sequence and inhibitory potency of different NNPIs with single amino acid substitutions tested on CTSK (c) or CTSL (d) compared to NNPI-E15 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). e, f) Sequence and inhibitory potency of different NNPIs with alternative single amino acid substitutions tested on CTSK (e) or CTSL (f) compared to the most potent NNPIs identified in the previous screening step (labeled in dark blue). The best NNPIs identified are labeled in light blue (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). g, h) Sequence and inhibitory potency of different NNPIs combining up to 3 amino acid changes compared to NNPI-E15 (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown), tested on CTSK (g) or CTSL (h). The most potent NNPIs are labeled in red.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Assessment of covalent bond formation between NNPI-C10 and CTSS.

a) Fluorescence and coomassie blue staining of gel loaded with CTSS alone or incubated with AF488-derivatized NNPI-C10. Different concentrations of E64 were tested to assess if NNPI-C10 could be displaced from CTSS. Images of 1 out of 2 independent experiments represented. b) Molecular structure of NNPI-C10-NC, differing from C10 because of a single bond replacing the double bond in the Michael acceptor. c) Intact mass spectrometry analysis of CTSS in complex with NNPI-C10 (red peaks) compared to CTSS alone (black peaks), performed in denaturing conditions.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Crystal structures of NNPI-C10 in complex with CTSS.

a, b) Superposed crystal structures of CTSS WT (grey) and CTSS Y132D (blue). Backbone structure of NNPI-C10 represented in purple. Active cysteine represented in yellow, aspartate 132 in red, histidine and asparagine from the catalytic triad in orange. c) Proximity of histidine in position 2 of NNPI-C10 and phenylalanine 184 of CTSS (highlighted in light blue). d) Position of tryptophan at the C-terminus of NNPI-C10 and phenylalanine 260 and tryptophan 300 of CTSS (highlighted in light blue). Histidine 278 of CTSS is also highlighted in red. e) Summary of hydrogen bonds identified between NNPI-C10 and CTSS Y132D.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Antibody-peptide inhibitor conjugates (APIC) characterization.

a) Intact mass spectrometry analysis of the αCD22-C10 APIC (black peaks) compared to the unconjugated αCD22 antibody (red peaks). b) Mass photometry analyses of CTSS, αCD79 antibody or αCD79-C10 APIC alone or incubated together. APIC conjugated with a 2-fold, 4-fold or 8-fold molar excess of C10-NNPI was used. CTSS was always used in 10-fold molar excess to antibody or APIC. Histograms represented in Fig. 2c were obtained by overlaying data from this experiment. c, d) Flow cytometry analysis of CD22 (c) and HER2 (d) surface receptor expression in different B cell lymphoma (WSU-DLCL2, SU-DHL-4, Raji, Ly-19), breast cancer (HCC-1569, BT-474) and bladder cancer (RT-4) cell lines. One representative histogram per cell line is shown (n = 2 per cell line). e) Flow cytometry analysis of SU-DHL-4 lymphoma cells stained with AF-488 labeled APIC. An anti-AF-488 antibody was used to quench the signal of the fluorophore and assess the internalization of the APIC at 4 °C and 37 °C (n = 2 per condition).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Cathepsin inhibition by APICs in cellular assays.

a, b) CTSS inhibition in Raji cells (a) or human donor primary B cells (b) treated with αCD79 APIC or petesicatib, assessed by BMV109 quenched activity-based probe (qABP). c) CTSB inhibition in RT-4 bladder cancer cells assessed by BMV109 qABP. d) Dose-dependent CTSS inhibition in Raji cells treated with increasing concentration of αCD79 APIC assessed by BMV109 quenched activity-based probe (qABP).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Functional effects of in vitro antibody-peptide inhibitor conjugate treatment of tumor cells.

a, b) CD74 accumulation measured by flow cytometry in Karpas-422 (a, n = 4 independent wells per condition) and Raji (b, n = 6 independent wells per condition) cells after 48 h incubation with APIC (red), unconjugated antibody (grey) or PBS (black). Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) normalized to PBS condition. P-value was determined by two-tailed t-test. c) CD74 accumulation measured by flow cytometry in Karpas-422 and WSU-DLCL2 cells overexpressing CTSS Y132D mutant form, after a 48 h treatment with αCD22 APIC. MFI normalized to signal in control antibody-treated cells (n = 2 independent wells treated per condition). d) Quantification of FRET assay assessing murine CTSS inhibition at increasing NNPI-C10 concentrations (n = 3 independent replicates; mean and SD values are shown). e) Murine CTSS inhibition in A20 cells treated with αCD79 APIC or petesicatib, assessed by BMV109 qABP. Lysate from untreated CTSS KO A20 cells was loaded as control.

Extended Data Fig. 9 APIC efficacy in T cell assay and transwell assay.

a) CD74 accumulation measured by flow cytometry in A20 cells after 24 h incubation with APIC (red), unconjugated antibody (grey) or PBS (black). Petesicatib (blue) and respective DMSO control (black) were tested in parallel. MFI normalized to PBS condition (n = 2 independent wells treated per condition). b, c) Proliferation score (b) and representative proliferation peaks (c) of CD8 T cells measured by flow cytometry after 72 hours of co-culture upon treatment with APIC (red), control antibody (grey), PBS (black) or Petesicatib (dark blue). CTSS KO A20 cells (dark red) and B2m KO A20 cells (blue) were included as controls (n = 3 independent wells treated per condition; mean and SD values are shown). P-value was determined by two-tailed t-test. d) Comparison of proliferation score of CD8 T cells co-cultured with A20 WT versus B2m KO lymphoma cells, measured by flow cytometry after 72 hours of co-culture upon treatment with APIC, control antibody or PBS (n = 3 independent wells treated per condition; mean and SD values are shown). P-value was determined by two-tailed t-test. e) Viability and cell density of HCC-1569 breast cancer cells after 48 hour treatment with APIC (red), control antibody (grey) or PBS (black) (n = 3 independent wells treated per condition; mean and SD values are shown). P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Biodistribution and in vivo efficacy of antibody-peptide inhibitor conjugates in human xenograft and syngeneic lymphoma mouse models.

a) Fused coronal SPECT/CT images at 48/72 hours post-injection of [111In]NOTA-αCD79 APIC in NSG mice bearing Raji subcutaneous tumors. Tumor mass indicated by a white arrow (n = 2 per condition). b) Biodistribution of [111In]NOTA-αCD79 APIC (red, n = 3; mean and SD values shown) in Raji tumor-bearing NSG mice. To demonstrate CD79 specificity of [111In]NOTA-APIC uptake, a 1 mg excess of unlabeled APIC was co-injected (orange, n = 3; mean and SD values shown). c) Fused coronal SPECT/CT images at 48/72 hours post-injection of [111In]NOTA-αCD22 APIC in NSG mice bearing Raji tumors (mass indicated by white arrow). d) Biodistribution of [111In]NOTA-αCD22 (blue, n = 4; mean and SD values shown) in Raji tumor-bearing mice. To demonstrate specificity, a 1 mg excess of unlabeled APIC was co-injected (dark blue, n = 3). e) Negative correlation between the percentage of B cells and CD8+ T cells in the spleen of mice treated with APIC (red, n = 5) or unconjugated anti-mCD79 antibody (black, n = 5) and a CTSS KO control mouse. A straight line was fitted by simple linear regression. P-value was determined by two-tailed F-test. f) Flow cytometry quantification of CD8+ T cells in the spleen of mice treated with APIC (red) or anti-mCD79 antibody (gray) (n = 5 mice per group). One age-matched control CTSS KO mouse (dark red) was included as reference. g) Representative images of multicolor immunofluorescence of the spleen of a vavP-Bcl2 CTSS KO mouse. Markers: B220 for B cells (blue), CD4 for CD4+ T cells (green), and CD8 for CD8+ T cells (red). A representative region of the larger spleen section stained is shown. h) Flow cytometry quantification of CD45+ cells in the spleen of mice treated with APIC (red) or anti-mCD79 antibody (gray) (n = 5 mice per group). One age-matched control CTSS KO mouse (dark red) was included as reference. i) Evolution of body weight of mice treated with APIC (red) or unconjugated anti-mCD79 antibody (black) (n = 5 mice per group; mean and SD values shown). In panels f and h, the central line of boxplots indicates the median value, whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum value; box limits correspond to the 25th-75th percentiles. P-values were determined by two-tailed t-test.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1, Table 1 and Methods.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Fig. 1 and full list of peptides in NNPI libraries.

Source Data Fig. 2

Uncropped gel related to Fig. 2a (fluorescence and Coomassie images).

Source Data Fig. 3

Uncropped western blot related to Fig. 3d.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Petruzzella, A., Bruand, M., Santamaria-Martínez, A. et al. Antibody–peptide conjugates deliver covalent inhibitors blocking oncogenic cathepsins. Nat Chem Biol 20, 1188–1198 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01627-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01627-z

This article is cited by

-

HACD3 promotes malignant progression of NSCLC by suppressing the MKK7/MAPK10 signaling axis

BMC Cancer (2025)

-

Designing supramolecular catalytic systems for mammalian synthetic metabolism

Nature Reviews Materials (2025)

-

Unraveling Cathepsin S regulation in interleukin-7-mediated anti-tumor immunity reveals its targeting potential against oral cancer

Journal of Biomedical Science (2025)