Abstract

Allosteric modulation of receptor responses to endogenous agonists has therapeutic value, maintaining ligand profiles, reducing side effects and restoring mutant responses. Adhesion G-protein-coupled receptors (aGPCRs), with large N termini, are ideal for allosteric modulator development. We designed a nanobody strategy targeting ADGRG2 N-terminal fragments and got a specific nanobody Nb23-bi, which promoted dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)-induced ADGRG2 activation and reversed mutant-induced dysfunctions. By combining structural characterization, crosslinking mass spectrometry, mutational analysis and molecular dynamics simulations, we clarified the allosteric mechanism of how the Nb23-bi modulates conformational changes in the DHEA-binding pocket. Animal studies showed that Nb23-bi promoted the response of DHEA in alleviating testicular inflammation and reversing mutant defects. In summary, we developed an allosteric nanobody of ADGRG2 and gained insights into its functions in reversing disease-associated dysfunctions. Our study may serve as a template for developing allosteric modulators of other aGPCRs for biological and therapeutic purposes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated in this study are included in the main text or Supplementary Information. The cryo-EM density map and the atomic coordinates were deposited to the EM Data Bank and PDB under accession codes EMD-39365 and 8YKD, respectively. RNA-sequencing data were deposited to the Gene Expression Ominibus under accession number GSE290996. The LC–MS/MS raw data were deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium under PRIDE access number PXD054996. The 64-nb MD model is available on figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28557683.v1)69. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bassilana, F., Nash, M. & Ludwig, M. G. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors: opportunities for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 869–884 (2019).

Bondarev, A. D. et al. Opportunities and challenges for drug discovery in modulating adhesion G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) functions. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 15, 1291–1307 (2020).

Hamann, J. et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCIV. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors. Pharm. Rev. 67, 338–367 (2015).

Purcell, R. H. & Hall, R. A. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors as drug targets. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 58, 429–449 (2018).

Paavola, K. J. & Hall, R. A. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors: signaling, pharmacology, and mechanisms of activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 82, 777–783 (2012).

Xiao, P. et al. Tethered peptide activation mechanism of the adhesion GPCRs ADGRG2 and ADGRG4. Nature 604, 771–778 (2022).

Scholz, N. et al. Molecular sensing of mechano- and ligand-dependent adhesion GPCR dissociation. Nature 615, 945–953 (2023).

Mitgau, J. et al. The N terminus of adhesion G protein-coupled receptor GPR126/ADGRG6 as allosteric force integrator. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 873278 (2022).

Liebscher, I., Schoneberg, T. & Thor, D. Stachel-mediated activation of adhesion G protein-coupled receptors: insights from cryo-EM studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 227 (2022).

Kuffer, A. et al. The prion protein is an agonistic ligand of the G protein-coupled receptor ADGRG6. Nature 536, 464–468 (2016).

Diamantopoulou, E. et al. Identification of compounds that rescue otic and myelination defects in the zebrafish adgrg6 (gpr126) mutant. eLife 8, e44889 (2019).

Ping, Y. Q. et al. Structural basis for the tethered peptide activation of adhesion GPCRs. Nature 604, 763–770 (2022).

Lin, H. et al. Structures of the ADGRG2–Gs complex in apo and ligand-bound forms. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 1196–1203 (2022).

An, W. et al. Progesterone activates GPR126 to promote breast cancer development via the Gi pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2117004119 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Optimization of a peptide ligand for the adhesion GPCR ADGRG2 provides a potent tool to explore receptor biology. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100174 (2021).

Mao, C. et al. Conformational transitions and activation of the adhesion receptor CD97. Mol. Cell 84, 570–583 (2024).

Ping, Y. Q. et al. Structures of the glucocorticoid-bound adhesion receptor GPR97–Go complex. Nature 589, 620–626 (2021).

Paavola, K. J., Sidik, H., Zuchero, J. B., Eckart, M. & Talbot, W. S. Type IV collagen is an activating ligand for the adhesion G protein-coupled receptor GPR126. Sci. Signal. 7, ra76 (2014).

Petersen, S. C. et al. The adhesion GPCR GPR126 has distinct, domain-dependent functions in Schwann cell development mediated by interaction with laminin-211. Neuron 85, 755–769 (2015).

Liu, D. et al. CD97 promotes spleen dendritic cell homeostasis through the mechanosensing of red blood cells. Science 375, eabi5965 (2022).

Kenakin, T. & Christopoulos, A. Measurements of ligand bias and functional affinity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 483 (2013).

Wootten, D., Christopoulos, A. & Sexton, P. M. Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: implications for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 630–644 (2013).

Peterson, S. M. et al. Discovery and design of G protein-coupled receptor targeting antibodies. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 18, 417–428 (2023).

Zhang, D. L. et al. Gq activity- and β-arrestin-1 scaffolding-mediated ADGRG2/CFTR coupling are required for male fertility. eLife 7, e33432 (2018).

Davies, B. et al. Targeted deletion of the epididymal receptor HE6 results in fluid dysregulation and male infertility. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8642–8648 (2004).

Yang, B. et al. Pathogenic role of ADGRG2 in CBAVD patients replicated in Chinese population. Andrology 5, 954–957 (2017).

Yuan, P. et al. Expanding the phenotypic and genetic spectrum of Chinese patients with congenital absence of vas deferens bearing CFTR and ADGRG2 alleles. Andrology 7, 329–340 (2019).

Rutkowski, K., Sowa, P., Rutkowska-Talipska, J., Kuryliszyn-Moskal, A. & Rutkowski, R. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): hypes and hopes. Drugs 74, 1195–1207 (2014).

Savineau, J. P., Marthan, R. & Dumas de la Roque, E. Role of DHEA in cardiovascular diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85, 718–726 (2013).

Jankowski, C. M. et al. Sex-specific effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on bone mineral density and body composition: a pooled analysis of four clinical trials. Clin. Endocrinol. 90, 293–300 (2019).

Alexaki, V. I. et al. DHEA inhibits acute microglia-mediated inflammation through activation of the TrkA–Akt1/2–CREB–Jmjd3 pathway. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1410–1420 (2018).

Cao, J., Lu, M., Yan, W., Li, L. & Ma, H. Dehydroepiandrosterone alleviates intestinal inflammatory damage via GPR30-mediated Nrf2 activation and NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition in colitis mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 172, 386–402 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. The influence of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on fasting plasma glucose, insulin levels and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther. Med. 55, 102583 (2020).

Srinivasan, M. et al. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone replacement on lipoprotein profile in hypoadrenal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 761–764 (2009).

Peixoto, C. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 17, 706–711 (2018).

Saijo, K., Collier, J. G., Li, A. C., Katzenellenbogen, J. A. & Glass, C. K. An ADIOL–ERβ–CtBP transrepression pathway negatively regulates microglia-mediated inflammation. Cell 145, 584–595 (2011).

Villareal, D. T. & Holloszy, J. O. Effect of DHEA on abdominal fat and insulin action in elderly women and men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 292, 2243–2248 (2004).

McMahon, C. et al. Yeast surface display platform for rapid discovery of conformationally selective nanobodies. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 289–296 (2018).

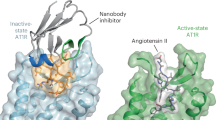

Wingler, L. M., McMahon, C., Staus, D. P., Lefkowitz, R. J. & Kruse, A. C. Distinctive activation mechanism for angiotensin receptor revealed by a synthetic nanobody. Cell 176, 479–490 (2019).

Kanner, S. A., Shuja, Z., Choudhury, P., Jain, A. & Colecraft, H. M. Targeted deubiquitination rescues distinct trafficking-deficient ion channelopathies. Nat. Methods 17, 1245–1253 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Hedgehog pathway activation through nanobody-mediated conformational blockade of the Patched sterol conduit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 28838–28846 (2020).

Staus, D. P. et al. Allosteric nanobodies reveal the dynamic range and diverse mechanisms of G-protein-coupled receptor activation. Nature 535, 448–452 (2016).

Bokoch, M. P. et al. Ligand-specific regulation of the extracellular surface of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 463, 108–112 (2010).

DeVree, B. T. et al. Allosteric coupling from G protein to the agonist-binding pocket in GPCRs. Nature 535, 182–186 (2016).

Koenig, P. A. et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Science 371, eabe6230 (2021).

Schoof, M. et al. An ultrapotent synthetic nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by stabilizing inactive Spike. Science 370, 1473–1479 (2020).

Wang, J. H. et al. Characterization of protein unfolding by fast cross-linking mass spectrometry using di-ortho-phthalaldehyde cross-linkers. Nat. Commun. 13, 1468 (2022).

van Zundert, G. C. P. et al. The HADDOCK2.2 web server: user-friendly integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 720–725 (2016).

Barad, D. H. & Gleicher, N. Increased oocyte production after treatment with dehydroepiandrosterone. Fertil. Steril. 84, 756 (2005).

Barad, D. & Gleicher, N. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on oocyte and embryo yields, embryo grade and cell number in IVF. Hum. Reprod. 21, 2845–2849 (2006).

Gleicher, N., Weghofer, A. & Barad, D. H. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) reduces embryo aneuploidy: direct evidence from preimplantation genetic screening (PGS). Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8, 140 (2010).

Nagels, H. E., Rishworth, J. R., Siristatidis, C. S. & Kroon, B.Androgens (dehydroepiandrosterone or testosterone) for women undergoing assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD009749 (2015).

Zhang, M. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone treatment in women with poor ovarian response undergoing IVF or ICSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 33, 981–991 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone administration before in vitro fertilization on the live birth rate in poor ovarian responders according to the Bologna criteria: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 129, 1030–1038 (2022).

Haubrich, J. et al. A nanobody activating metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 discriminates between homo- and heterodimers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2105848118 (2021).

Krishna Kumar, K. et al. Negative allosteric modulation of the glucagon receptor by RAMP2. Cell 186, 1465–1477 (2023).

Xiang, Y. et al. Versatile and multivalent nanobodies efficiently neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Science 370, 1479–1484 (2020).

de Wit, R. H. et al. CXCR4-specific nanobodies as potential therapeutics for WHIM syndrome. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 363, 35–44 (2017).

Peyrassol, X. et al. Development by genetic immunization of monovalent antibodies (nanobodies) behaving as antagonists of the human ChemR23 receptor. J. Immunol. 196, 2893–2901 (2016).

Hannan, F. M., Kallay, E., Chang, W., Brandi, M. L. & Thakker, R. V. The calcium-sensing receptor in physiology and in calcitropic and noncalcitropic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 33–51 (2018).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 (2015).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 213–221 (2010).

Yang, F. et al. Structural basis of GPBAR activation and bile acid recognition. Nature 587, 499–504 (2020).

Guimaraes, C. P. et al. Site-specific C-terminal and internal loop labeling of proteins using sortase-mediated reactions. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1787–1799 (2013).

Tribello, G. A., Bonomi, M., Branduardi, D., Camilloni, C. & Bussi, G. PLUMED 2: new feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604–613 (2014).

Huang, S. M. et al. Single hormone or synthetic agonist induces Gs/Gi coupling selectivity of EP receptors via distinct binding modes and propagating paths. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2216329120 (2023).

Zhang, C. The 64-nanobody MD model. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28557683.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars grant (81825022 to J.-P.S. and 82225011 to X.Y.), National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (32222038 to P.X.), New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the New Cornerstone Investigator Program (to J.-P.S.), State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (32130055 and 2024YFA0916900 to J.-P.S.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773704 and 32361163612 to J.-P.S., 92057121 to X.Y., 82220108005, 92468205 to S.-Q.F., 82371629 to D.-L.Z., 82304583 to H.L., 82304601 to S.-M.H., 32201065 to Y.L., 92353303 and 82421004 to F. Yang, 82371633 to H.-C.L.), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (ZR2024JQ013 to P.X.), Taishan Scholars Program (tsqn202211015 to P.X., tsqn202408054 to S.-M.H.), Cutting Edge Development Fund of Advanced Medical Research Institute (to J.-P.S. and H.L.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M732092 and BX20230207 to H.L. and 2022M711916 to Y.L.), Innovative Research Team of High-Level Local Universities in Shanghai (SHSMU-ZLCX20212301 to P.X.), Peking University Clinical Scientist Training Program and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (BMU2023PYJH012 to H.-C.L.), Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (7212134 to H.-C.L.) and National Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023ZD16 to S.-Q.F.). The cryo-EM data were collected at the Biomedical Research Center for Structural Analysis of Shandong University. We thank L. Qi of the Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for consultation and instrument availability that supported this work. We thank L. Wang of the Flow Cytometry System at the Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for data analysis. The scientific calculations in this study were performed using the HPC Cloud Platform at Shandong University. We thank F. Wang of the MS System at Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-Q.F. and J.-P.S. conceptualized and supervised the overall project; J.-P.S., P.X., L.H. and X.Y. designed all experiments and analyzed the data. Y.Z. and D.J. were responsible for the screening of nanobodies, affinity identification and signal detection work. S.-M.H. and S.-C.G. generated the ADGRG2 insect expression constructs, assembled protein complexes and determined their structures. J.-F.H. and J.C. prepared Nb35 for the formation of the complex. Y.Z. and D.J. initiated the functional study of ADGRG2 and its mutants and the FlAsH-BRET assay. Y.Z., D.J. and H.-C.L. performed the ADGRG2 ligand-binding assay and β-arrestin 1 recruitment assay. Y.L. conducted the CLMS experiments and analysis. C.Z. mainly focused on the content of MD simulations. H.L., D.J., D.-L.Z, H.-C.L. and Y.Z. were responsible for establishing disease animal models, detecting animal inflammatory factors and performing testicular slice statistics and other related animal experiments. Y.-X.H., M.-X.Z. and Y.-H.G. participated in data analysis of animal experiments. R.W. and M.X. helped to analyze the CLMS experiments. Y.-Y.G. and Y.-Y.Q. participated in the G-protein trimer dissociation assay. X.Y., Z.-Q.L., S.-H.G. and F. Yi provided mice for animal experiments and participated in the data analysis. F. Yang and P. X. participated in the structural analysis work. J.-P.S., S.-Q.F. and X.Y. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Daiji Kiyozumi, Simone Prömel and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Discovery of the nanobodies selectively target the NTF of ADGRG2.

a. Gating strategy to separate ADGRG2-NTF binding yeast cells in the enriched yeast library by flow cytometry sorting (FACS). DHEA-ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex were labeled with AF647 and DHEA-ADGRG2-βt-Gs complex were labeled with FITC. The unstained yeast cells(left) were used as negative control. Only single AF647 positive cells in gate were sorted for downstream analysis (middle). Flow cytometry plot indicating that yeast cells only interacting with the DHEA-ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex were successfully separated by FACS selection(right). Labels indicate % of cells within each gate. b-c. Representative SDS-PAGE of co-immunoprecipitation of purified Nb23 (b) or Nb32 (c) with purified ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex shows it prefer for receptor bound to agonists (DHEA) compared to unliganded (Apo) bound ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex. d. ADGRG2 protein expressed on the membrane lysates of TM3 and TM4 cell (left), and the ATP1A1 is shown as the internal control of cell membrane (right). Representative western blot images three independent experiments were shown (n = 3). e. Binding of nanobodies to ADGRG2-FL as demonstrated by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry data from three independent experiments were shown (n = 3). f. Binding of nanobodies to TM4 cells, as demonstrated by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry data from three independent experiments were shown (n = 3). g. Binding of nanobodies to ADGRG2-βt as demonstrated by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry data from three independent experiments were shown (n = 3).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Identification and optimization of nanobodies as PAMs of ADGRG2.

a. Representative dose-response curves from three independent experiments of two ADGRG2 FlAsH-BRET sensors in response to Nb23, Nb32 or Nb6 stimulation (n = 3) are shown. The EC50 values are the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). b. Representative saturation binding curves from three independent experiments of Nb23-FITC, Nb32-FITC, Nb23-bi-FITC, Nb32-bi-FITC toward Nluc–ADGRG2 (n = 3) are shown. FITC is conjugated at the C terminus of the nanobodies. c, Representative dose–response curves from three independent experiments of DHEA-induced cAMP accumulation in mADGRG2-overexpressing HEK293 cells treated with or without 1 μM nanobodies, as determined by the GloSensor assay (n = 3) are shown. The curve representing DHEA-induced ADGRG2 activation in right panel is a replica of the corresponding curve in left panel, depicted as a dotted line to facilitate comparison and enhance clarity in the evaluation. The EC50 values are presented as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). d. Representative dose-response curves from three independent experiments of DHEA-induced InsP3 (IP3) production in mADGRG2-overexpressing HEK293 cells treated with or without 1 μM nanobodies (n = 3) are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Functional modulation and molecular dynamics analysis of DHEA and ADGRG2 interaction with or without Nb23-bi.

a. Effects of mADGRG2 mutants on DHEA-induced cAMP accumulation with or without Nb23-bi. Each value is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n = 3). SR with Nb23-bi: the specific interacting residues found in the Nb23-bi-DHEA-mADGRG2-Gs complex; SR without Nb23-bi: the specific interacting residues found in DHEA-mADGRG2-Gs complex; CR: the common interacting residues found in the two complexes; NR: the residues had no interaction with the two complex. Statistical differences in the DHEA or DHEA+Nb23bi-induced activation of wild-type mADGRG2 and that of its mutants were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s test. DHEA-induced activation of wild-type mADGRG2 and that of its mutants (green); DHEA+Nb23-bi-induced activation of wild-type mADGRG2 and that of its mutants (purple). ND, not detected. b. Contact frequency plots of the interaction between DHEA and the binding site residues in the DHEA-ADGRG2 system with or without Nb23-bi were obtained from MD simulations in 2000 ns. The frequency of interactions in Nb23-bi-DHEA-ADGRG2 is shown in purple, and that in DHEA-ADGRG2 is shown in green. c. The key amino acids of ECL2 interacting with DHEA in Nb23-bi-DHEA-ADGRG2-FL in MD simulation. d. The ECL2 residues interacting with DHEA in the DHEA-ADGRG2-FL and Nb23bi-DHEA-mADGRG2-FL systems through MD simulation or in the Cryo-EM structure. e-f. Calculation of the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the residues in binding pocket that interact with DHEA (e) and DHEA itself (f) in MD simulations with or without Nb23-bi. The RMSD values are the mean ± SEM from three independent simulation in triplicate.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Structural rearrangement of the extracellular side of 7TM in ADGRG2 during activation.

a. The flowchart of building the inactive ADGRG2 model by MD simulations. b. RMSDs of Cα atoms of the inactive ADGRG2 model in MD simulation. c. The structural rearrangement of the extracellular side of 7TM in the inactive ADGRG2 model compared to active ADGRG2 mode. d. The conformational rearrangements of TM1 and ECLs in the Nb23-bi-DHEA-ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex were compared to those in the DHEA-ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex. e-h. In the Nb23-bi-DHEA-ADGRG2-FL-Gs complex, the Cα atoms of residues T6211.40 has undergone a counterclockwise rotation of approximately 15°, along with an outward rotation of 65° for the side chain of L6201.39 (e) and an inward rotation of 80° for Y6251.44 (f). The rearrangements of L6201.39 and Y6251.44 affect the hydrophobic interactions with M8537.39-Y8547.40 and the π-π packing interaction with W6762.69 (e, h), which further induce the change of ECL3 and ECL1. The ECL2 rotated downward to the 7TM core by 180° (g).

Extended Data Fig. 5 CLMS analysis of the Nb23-bi-DHEA-ADGRG2-Gs complex by two cross-linkers (DOPA2 or DSS).

a. Annotated MS/MS spectrum of the DOPA2-linked intermolecular peptide pair. b. Annotated MS/MS spectrum of the DSS-linked intermolecular peptide pair. The same two cross-links identified by both DSS and DOPA2 were not shown. c-d. Table of the cross-linked pairs identified between ADGRG2 and Nb23-bi following treatment with DOPA2 (c) or DSS (d). Numbers indicate positions of lysines cross-linked on ADGRG2 or Nb23-bi; Cross-linked residue in peptide sequence is highlighted in bold.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Cross-linking mass spectrometry for analysis of Nb23-bi binding to ADGRG2.

a. Schematic representation showing the mutational design of Nb23-bi. b. Cross-linking MS was used to investigate the potential interfaces between Nb23-bi and ADGRG2. c-d. Annotated MS/MS spectrum of the DSS-linked intermolecular peptide pair consisting of K201C.s14s15 of Nb23-bi with K88A.h1 of ADGRG2(c) and K64N.s5s6 of Nb23-bi with K149A.h2 of ADGRG2(d). e. The Nb23-bi-ADGRG2 model was supported by cross-linking MS analysis. K88A.h1 on the α1-helix of ADGRG2N-term was cross-linked with K201C.s14s15 on the C domain of Nb23-bi, while K149A.h2 on the α2-helix of ADGRG2N-term was cross-linked with K64N.s5s6 on the N domain of Nb23-bi. The cross-links are highlighted with red lines, the cross-linked lysine are presented in red stars. The α-helix of ADGRG2N-term are shown in green, the N domain and C domain of Nb23-bi are shown in blue and yellow respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The anti-inflammation effects of DHEA via ADGRG2 in LPS-induced testicular inflammation model.

a. Schematic diagram of mouse experiments. b. Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in testis of LPS-induced wild-type mice treated with LPS compared to genes in testis tissue of those sham group. Statistical differences were determined by two-sided Student’s t test. c. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotation of signaling pathway changes determined by whole-transcriptome RNA-seq analysis of isolated testis tissue from wild-type mice treated with LPS and the control vehicle compared to those treated with PBS only. GPI-anchored: Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins BR; GAG binding: Glycosaminoglycan binding proteins BR; steroidogenesis: Ovarian steroidogenesis; Antigene: Antigen processing and presentation; Steroid hormone: Steroid hormone biosynthesis; Hematopoietic cell: Hematopoietic cell lineage; IIN for IgA: Intestinal immune network for IgA production. d. Heatmap visualization of representative differentially-regulated genes derived from whole transcriptome RNA-seq analysis of wild type mice testis. Red color represents the differences in the mRNA levels of the indicated genes, which were normalized to the levels in LPS treated mouse samples. e. The mRNA levels of Ccl2, Ccl5 and Cxcl13 determined by qPCR of testis tissue isolated from WT and Adgrg2-/Y mice. The data are from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s test. f. Protein levels of the cytokines CCL2, CCL5 and CXCL13 in testis tissue isolated from wild-type or Adgrg2-/Y mice, determined by ELISA (n = 3). Statistical differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s test.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The disease-related SNPs of the human ADGRG2.

a. Schematic diagram of the disease-related SNPs of human ADGRG2 in the Nb23-bi binding structural model. b. Sequence comparisons of human ADGRG2 and mouse ADGRG2 in the interface of Nb23-bi. c-g. Representative dose-response curves from three independent experiments of DHEA-induced cAMP accumulation in HEK293 cells overexpressing wild-type hADGRG2 (c) or its mutants (d-g) treated with or without 1 μM Nb23-bi, as determined by the GloSensor assay (n = 3) are shown. h. Protein levels of the cytokines CXCL13 in testis samples isolated from Adgrg2-/Y mice injected with WT or mutant hADGRG2, determined by ELISA. The data are from four independent experiments (n = 4). Statistical differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s test.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–15 and Tables 1–5.

Supplementary Data 1

MD model of Nb23-bi interaction with ADGRG2.

Supplementary Data 2

Statistical source data of supplementary figures.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Jiang, D., Lu, Y. et al. Development of an allosteric adhesion GPCR nanobody with therapeutic potential. Nat Chem Biol 21, 1519–1530 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01896-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01896-2

This article is cited by

-

Progress on Omega-3 fatty acids for the comprehensive and targeted treatment of spinal cord injury

Bone Research (2026)

-

Molecular insights into ligand recognition and signaling of OXGR1

Nature Communications (2025)