Abstract

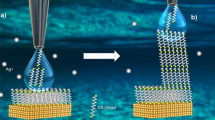

Stimulus-responsive materials have enabled advanced applications in biosensing, tissue engineering and therapeutic delivery. Although controlled molecular topology has been demonstrated as an effective route toward creating materials that respond to prespecified input combinations, prior efforts suffer from a reliance on complicated and low-yielding multistep organic syntheses that dramatically limit their utility. Harnessing the power of recombinant expression, we integrate emerging chemical biology tools to create topologically specified protein cargos that can be site-specifically tethered to and conditionally released from biomaterials following user-programmable Boolean logic. Critically, construct topology is autonomously compiled during expression through spontaneous intramolecular ligations, enabling direct and scalable synthesis of advanced operators. Using this framework, we specify protein release from biomaterials following all 17 possible YES/OR/AND logic outputs from input combinations of three orthogonal protease actuators, multiplexed delivery of three distinct biomacromolecules from hydrogels, five-input-based conditional cargo liberation and logically defined protein localization on or within living mammalian cells.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All pertinent experimental and characterization data are available within this paper and its associated Supplementary Information. Plasmids generated during the current study are listed in the Supplementary Information and are available through Addgene. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Badeau, B. A. & DeForest, C. A. Programming stimuli-responsive behavior into biomaterials. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 21, 241–265 (2019).

Liu, A. P. et al. The living interface between synthetic biology and biomaterial design. Nat. Mater. 21, 390–397 (2022).

Narkar, A. R., Tong, Z., Soman, P. & Henderson, J. H. Smart biomaterial platforms: controlling and being controlled by cells. Biomaterials 283, 121450 (2022).

Li, J. & Mooney, D. J. Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16071 (2016).

Rizzo, F. & Kehr, N. S. Recent advances in injectable hydrogels for controlled and local drug delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001341 (2021).

Drury, J. L. & Mooney, D. J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials 24, 4337–4351 (2003).

Malda, J. et al. 25th anniversary article: engineering hydrogels for biofabrication. Adv. Mater. 25, 5011–5028 (2013).

Aisenbrey, E. A. & Murphy, W. L. Synthetic alternatives to Matrigel. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 539–551 (2020).

Hofer, M. & Lutolf, M. P. Engineering organoids. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 402–420 (2021).

Johnston, T. G. et al. Compartmentalized microbes and co-cultures in hydrogels for on-demand bioproduction and preservation. Nat. Commun. 11, 563 (2020).

Fisher, S. A., Baker, A. E. G. & Shoichet, M. S. Designing peptide and protein modified hydrogels: selecting the optimal conjugation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7416–7427 (2017).

Shadish, J. A. & DeForest, C. A. Site-selective protein modification: from functionalized proteins to functional biomaterials. Matter 2, 50–77 (2020).

Gharios, R., Francis, R. M. & DeForest, C. A. Chemical and biological engineering strategies to make and modify next-generation hydrogel biomaterials. Matter 6, 4195–4244 (2023).

Gharios, R., Li, A., Kopyeva, I., Francis, R. M. & DeForest, C. A. One-step purification and N-terminal functionalization of bioactive proteins via atypically split inteins. Bioconjug. Chem. 35, 750–757 (2024).

Kloxin, A. M., Kasko, A. M., Salinas, C. N. & Anseth, K. S. Photodegradable hydrogels for dynamic tuning of physical and chemical properties. Science 324, 59–63 (2009).

Brown, T. E., Marozas, I. A. & Anseth, K. S. Amplified photodegradation of cell-laden hydrogels via an addition–fragmentation chain transfer reaction. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605001 (2017).

Chapla, R., Hammer, J. A. & West, J. L. Adding dynamic biomolecule signaling to hydrogel systems via tethered photolabile cell-adhesive proteins. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 8, 208–217 (2022).

Shadish, J. A., Strange, A. C. & DeForest, C. A. Genetically encoded photocleavable linkers for patterned protein release from biomaterials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15619–15625 (2019).

Kilic Boz, R. et al. Redox-responsive hydrogels for tunable and “on-demand” release of biomacromolecules. Bioconjug. Chem. 33, 839–847 (2022).

Lueckgen, A. et al. Enzymatically-degradable alginate hydrogels promote cell spreading and in vivo tissue infiltration. Biomaterials 217, 119294 (2019).

Tanimoto, R., Ebara, M. & Uto, K. Tunable enzymatically degradable hydrogels for controlled cargo release with dynamic mechanical properties. Soft Matter 19, 6224–6233 (2023).

Ding, H. et al. Preparation and application of pH-responsive drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 348, 206–238 (2022).

Burdick, J. A. & Murphy, W. L. Moving from static to dynamic complexity in hydrogel design. Nat. Commun. 3, 1269 (2012).

Zhao, Z., Ukidve, A., Kim, J. & Mitragotri, S. Targeting strategies for tissue-specific drug delivery. Cell 181, 151–167 (2020).

Manzari, M. T. et al. Targeted drug delivery strategies for precision medicines. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 351–370 (2021).

Culver, H. R., Clegg, J. R. & Peppas, N. A. Analyte-responsive hydrogels: intelligent materials for biosensing and drug delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 170–178 (2017).

Herrmann, A., Haag, R. & Schedler, U. Hydrogels and their role in biosensing applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2100062 (2021).

Ikeda, M. et al. Installing logic-gate responses to a variety of biological substances in supramolecular hydrogel–enzyme hybrids. Nat. Chem. 6, 511–518 (2014).

Hou, B., et al. Engineering stimuli-activatable Boolean logic prodrug nanoparticles for combination cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907210 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. A programmable polymer library that enables the construction of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers containing logic gates. Nat. Chem. 12, 381–390 (2020).

Gawade, P. M., Shadish, J. A., Badeau, B. A. & DeForest, C. A. Logic-based delivery of site-specifically modified proteins from environmentally responsive hydrogel biomaterials. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902462 (2019).

Ruskowitz, E. R., Comerford, M. P., Badeau, B. A. & DeForest, C. A. Logical stimuli-triggered delivery of small molecules from hydrogel biomaterials. Biomater. Sci. 7, 542–546 (2019).

Badeau, B. A., Comerford, M. P., Arakawa, C. K., Shadish, J. A. & DeForest, C. A. Engineered modular biomaterial logic gates for environmentally triggered therapeutic delivery. Nat. Chem. 10, 251–258 (2018).

Thompson, R. E. & Muir, T. W. Chemoenzymatic semisynthesis of proteins. Chem. Rev. 120, 3051–3126 (2020).

de la Torre, D. & Chin, J. W. Reprogramming the genetic code. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 169–184 (2021).

Scott, C. P., Abel-Santos, E., Wall, M., Wahnon, D. C. & Benkovic, S. J. Production of cyclic peptides and proteins in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13638–13643 (1999).

Iwai, H., Lingel, A. & Plückthun, A. Cyclic green fluorescent protein produced in vivo using an artificially split PI-PfuI intein from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16548–16554 (2001).

Zhang, W.-B., Sun, F., Tirrell, D. A. & Arnold, F. H. Controlling macromolecular topology with genetically encoded SpyTag–SpyCatcher chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13988–13997 (2013).

Schoene, C., Bennett, S. P. & Howarth, M. SpyRings declassified: a blueprint for using isopeptide-mediated cyclization to enhance enzyme thermal resilience. Methods Enzymol. 580, 149–167 (2016).

Fan, R. & Aranko, A. S. Catcher/Tag toolbox: biomolecular click-reactions for protein engineering beyond genetics. ChemBioChem 25, e202300600 (2024).

Qu, Z., Cheng, S. Z. D. & Zhang, W.-B. Macromolecular topology engineering. Trends Chem. 3, 402–415 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Mechano-bioconjugation strategy empowering fusion protein therapeutics with aggregation resistance, prolonged circulation, and enhanced antitumor efficacy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 18387–18396 (2022).

Bai, X. et al. Cellular synthesis of protein pretzelanes. Giant 10, 100092 (2022).

Hou, B., Yan, X., He, J., Zhang, W.-B. & Shao, Y. Self-assembly of three-component bolaform giant surfactants with branched architectures. Giant 15, 100165 (2023).

Snoj, J., Lapenta, F. & Jerala, R. Preorganized cyclic modules facilitate the self-assembly of protein nanostructures. Chem. Sci. 15, 3673–3686 (2024).

Bressler, E. M. et al. Boolean logic in synthetic biology and biomaterials: Towards living materials in mammalian cell therapeutics. Clin. Transl. Med. 13, e1244 (2023).

Campbell, B. C. et al. mGreenLantern: a bright monomeric fluorescent protein with rapid expression and cell filling properties for neuronal imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 30710–30721 (2020).

Dorr, B. M., Ham, H. O., An, C., Chaikof, E. L. & Liu, D. R. Reprogramming the specificity of sortase enzymes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13343–13348 (2014).

Bretherton, R. C., et al. User-controlled 4D biomaterial degradation with substrate-selective sortase transpeptidases for single-cell biology. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209904 (2023).

Kopyeva, I., et al. Stepwise stiffening/softening of and cell recovery from reversibly formulated hydrogel interpenetrating networks. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404880 (2024).

Keeble, A. H. et al. DogCatcher allows loop-friendly protein–protein ligation. Cell Chem. Biol. 29, 339–350 (2022).

Cabrita, L. D. et al. Enhancing the stability and solubility of TEV protease using in silico design. Protein Sci. 16, 2360–2367 (2007).

Zakeri, B. et al. Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E690–E697 (2012).

Stevens, A. J. et al. Design of a split intein with exceptional protein splicing activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2162–2165 (2016).

Thompson, R. E., Stevens, A. J. & Muir, T. W. Protein engineering through tandem transamidation. Nat. Chem. 11, 737–743 (2019).

Townend, J. E. & Tavassoli, A. Traceless production of cyclic peptide libraries in E. coli. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 1624–1630 (2016).

Veggiani, G. et al. Programmable polyproteams built using twin peptide superglues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1202–1207 (2016).

Xu, Q. et al. Catcher/Tag cyclization introduces electrostatic interaction mediated protein–protein interactions to enhance the thermostability of luciferase. Process Biochem. 80, 64–71 (2019).

Sun, F. & Zhang, W.-B. Genetically encoded click chemistry. Chin. J. Chem. 38, 894–896 (2020).

Evans, T. C., Benner, J. & Xu, M.-Q. The cyclization and polymerization of bacterially expressed proteins using modified self-splicing inteins. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18359–18363 (1999).

Siebold, C. & Erni, B. Intein-mediated cyclization of a soluble and a membrane protein in vivo: function and stability. Biophys. Chem. 96, 163–171 (2002).

Qi, X. & Xiong, S. Intein-mediated backbone cyclization of VP1 protein enhanced protection of CVB3-induced viral myocarditis. Sci. Rep. 7, 41485 (2017).

Oliveira-Silva, R. et al. Monitoring proteolytic activity in real time: a new world of opportunities for biosensors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 45, 604–618 (2020).

Agard, N. J., Prescher, J. A. & Bertozzi, C. R. A strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide–alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 15046–15047 (2004).

DeForest, C. A., Polizzotti, B. D. & Anseth, K. S. Sequential click reactions for synthesizing and patterning three-dimensional cell microenvironments. Nat. Mater. 8, 659–664 (2009).

Nallamsetty, S. et al. Efficient site-specific processing of fusion proteins by tobacco vein mottling virus protease in vivo and in vitro. Protein Expr. Purif. 38, 108–115 (2004).

Abdelkader, E. H. & Otting, G. NT*-HRV3CP: an optimized construct of human rhinovirus 14 3C protease for high-yield expression and fast affinity-tag cleavage. J. Biotechnol. 325, 145–151 (2021).

Qu, Z. et al. A single-domain green fluorescent protein catenane. Nat. Commun. 14, 3480 (2023).

Li, T., Zhang, F., Fang, J., Liu, Y. & Zhang, W.-B. Rational design and cellular synthesis of proteins with unconventional chemical topology. Chin. J. Chem. 41, 2873–2880 (2023).

Pruszynski, M., D’Huyvetter, M., Bruchertseifer, F., Morgenstern, A. & Lahoutte, T. Evaluation of an anti-HER2 nanobody labeled with 225Ac for targeted α-particle therapy of cancer. Mol. Pharm. 15, 1457–1466 (2018).

Burgstaller, S. et al. Monitoring extracellular ion and metabolite dynamics with recombinant nanobody-fused biosensors. iScience 25, 104907 (2022).

Roberts, P. J. et al. Rho family GTPase modification and dependence on CAAX motif-signaled posttranslational modification. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25150–25163 (2008).

Szymczak, A. L. et al. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 589–594 (2004).

Vizovišek, M., Fonović, M. & Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins in extracellular matrix remodeling: extracellular matrix degradation and beyond. Matrix Biol. 75–76, 141–159 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Optogenetic control with a photocleavable protein, PhoCl. Nat. Methods 14, 391–394 (2017).

Dang, B. et al. SNAC-tag for sequence-specific chemical protein cleavage. Nat. Methods 16, 319–322 (2019).

Fink, T. et al. Design of fast proteolysis-based signaling and logic circuits in mammalian cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 115–122 (2019).

Nguyen, D. P. et al. Genetic encoding of photocaged cysteine allows photoactivation of TEV protease in live mammalian cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2240–2243 (2014).

Chen, Z. et al. Programmable design of orthogonal protein heterodimers. Nature 565, 106–111 (2019).

Chin, J. W. Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code. Nature 550, 53–60 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Francis and A. Garcia for collaborating on designing and validating the SpyCatcher-azide, C. Yang and R. Brady for synthesizing and supplying PEG-tetraBCN and J. Davis for gifting HEK293T cells (previously obtained from the ATCC, CRL-3216). We acknowledge support from D. Whittington at the University of Washington MS Center. Part of this work was conducted with instrumentation provided by the Joint Center for Deployment and Research in Earth Abundant Materials. This work was supported by a grant (DMR 1807398, C.A.D.) from the National Science Foundation and a Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (R35GM138036, C.A.D.) from the National Institutes of Health. Student support was further provided through a John C. Berg Endowed Fellowship (R.G.), the National Science Foundation (DGE-2140004, M.L.R.), a Goldwater Scholarship (A.L.), a Washington NASA Space Grant (A.L), a University of Washington MEM-C Academic-Year Research Accelerator Fellowship (A.L) and a University of Washington Mary Gates Endowment for Students (S.P.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.G., M.L.R., and C.A.D. conceptualized and designed the experiments. R.G., M.L.R., A.L., S.P.K. and J.H. performed the experiments. R.G., M.L.R., A.L., S.P.K., J.H. and C.A.D. analyzed the data. C.A.D. prepared the main text figures with input from R.G. and M.L.R. C.A.D. and M.L.R. prepared the supplementary figures with input from R.G. R.G., M.L.R. and C.A.D. wrote the paper with input from all other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.A.D., R.G. and M.L.R. have filed a patent application (PCT/US2025/031504) related to the work described in this article. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Karthik Raman, Laura Sabio, Manuel Salmeron-Sanchez and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Mass spectrometric validation of logically releasable mGreenLantern.

a, YES-gated single-input tethers. b-c, Two-input (b) OR-gated and (c) AND-gated tethers. d-g, Three-input (d) OR/(AND)-, (e) AND/(OR)-, (f) OR/OR-, and (g) AND/AND-gated tethers. Plot titles correspond to the protein tether identity.

Extended Data Fig. 2 SDS-PAGE analysis of in-solution treatment of autonomously compiled mGreenLantern pendants.

a, mGreenLantern-A∧(S∨T) is differentially cleaved following the 8 possible input combinations of A, S, and T. Input conditions A, S, T, and ST are expected to linearize the product but not induce payload release, leading to a product with less electrophoretic mobility than the initial cyclic construct. Payload release is expected following input conditions AS, AT, and AST, accompanied with a product band that migrates further than the starting species. b, Changes in topology and/or molecular weight in response to a specific set of inputs leads to changes in protein electrophoretic mobility, which can be analyzed through gel densitometry. c, The response profiles of the YES-gated single-input tethers. d-e, The response profiles of the two-input (d) OR-gated and (e) AND-gated tethers. f-h, The response profiles of the three-input (f) OR/(AND)-, (g) AND/(OR)-, and (h) OR/OR-gated tethers. Plot titles correspond to the protein tether identity; the y-axis represents extent of cleavage as measured through migration on an SDS-PAGE with gel densitometry analysis; the x-axis indicates treatment conditions, wherein N indicates no treatment, A indicates eSrtA(2A9), S indicates eSrtA(4S9), and T indicates TEV. Green bars indicate conditions expected to yield tether cleavage, whereas red bars indicate conditions expected to keep the tether non-cleaved. Error bars correspond to ±1 standard deviation about the mean with propagated uncertainties for n = 3 experimental replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 3 SDS-PAGE analysis of in-solution treatment of autonomously compiled mCherry and mCerulean pendants.

a-c, Changes in topology and/or molecular weight in response to a specific set of inputs leads to changes in protein electrophoretic mobility, which can be analyzed through gel densitometry. Results are shown for species (a) mCherry-S, (b) mCerulean-T, and (c) mCerulean-S∧T. Plot titles correspond to the protein tether identity; the y-axis represents extent of cleavage as measured through migration on an SDS-PAGE with gel densitometry analysis; the x-axis indicates treatment conditions, wherein N indicates no treatment, A indicates eSrtA(2A9), S indicates eSrtA(4S9), and T indicates TEV. Error bars correspond to ±1 standard deviation about the mean with propagated uncertainties for n = 3 experimental replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Multiplexed YES-gated release of proteins from hydrogel biomaterials.

a, mGreenLantern-A, mCherry-S, and mCerulean-T are tethered homogenously into an underlying PEG-based hydrogel network via SpyLigation, each exhibiting a different YES-gated response. b, Appropriate proteins are individually released when their corresponding input is present. Fully colored bars (green for mGreenLantern, red for mCherry, blue for mCerulean) indicate conditions expected to yield protein release, whereas opaque colored bars denote conditions not expected to result in release. Error bars correspond to ±1 standard deviation about the mean with propagated uncertainties for n = 3 experimental replicates.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–16 and Methods.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 11 and 14.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gharios, R., Ross, M.L., Li, A. et al. Boolean logic-gated protein presentation through autonomously compiled molecular topology. Nat Chem Biol 21, 1981–1991 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02037-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02037-5

This article is cited by

-

Self-assembling information-processing biomaterial circuits

Nature Chemical Biology (2025)