Abstract

Seizures in people with epilepsy were long thought to occur at random, but recent methods for seizure forecasting enable estimation of the likelihood of seizure occurrence over short horizons. These methods rely on days-long cyclical patterns of brain electrical activity and other physiological variables that determine seizure likelihood and that require measurement through long-term, multimodal recordings. In this retrospective cohort study of 15 adults with bitemporal epilepsy who had a device that provides chronic intracranial recordings, functional connectivity of hippocampal networks fluctuated in multiday cycles with patterns that mirrored cycles of seizure likelihood. A functional connectivity biomarker of seizure likelihood derived from 90-s recordings of background hippocampal activity generalized across individuals and forecasted 24-h seizure likelihood as accurately as cycle-based models requiring months-long baseline recordings. Larger, prospective studies are needed to validate this approach, but our results have the potential to make reliable seizure forecasts accessible to more people with epilepsy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings in this article may be found within the article itself, the source data and our publicly available GitHub repository at https://github.com/khambhati-lab/pub-2024-hippocampal-seizure-forecasting. Raw RNS System data were obtained through a Data Use Agreement between UCSF and NeuroPace and cannot be publicly shared. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code used in the analyses can be found in a GitHub repository at https://github.com/khambhati-lab/pub-2024-hippocampal-seizure-forecasting.

References

Lehnertz, K. et al. Epileptic-network-based prediction and control of seizures in humans. Neurobiol. Dis. 181, 106098 (2023).

Karoly, P. J. et al. Cycles in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 267–284 (2021).

Baud, M. O. et al. Multi-day rhythms modulate seizure risk in epilepsy. Nat. Commun. 9, 88 (2018).

Stirling, R. E. et al. Seizure forecasting using a novel sub-scalp ultra-long term EEG monitoring system. Front. Neurol. 12, 713794 (2021).

Gregg, N. M. et al. Seizure occurrence is linked to multiday cycles in diverse physiological signals. Epilepsia 64, 1627–1639 (2023).

Kurup, D. et al. Comparing seizures captured by rapid response EEG and conventional EEG recordings in a multicenter clinical study. Front. Neurol. 13, 915385 (2022).

Andrzejak, R. G. et al. Seizure forecasting: where do we stand? Epilepsia 64, 62 (2023).

Baud, M. O. et al. Seizure forecasting: bifurcations in the long and winding road. Epilepsia 64, S78–S98 (2023).

Mormann, F. et al. Mean phase coherence as a measure for phase synchronization and its application to the EEG of epilepsy patients. Physica D 144, 358–369 (2000).

Rijal, S. et al. Functional connectivity discriminates epileptogenic states and predicts surgical outcome in children with drug resistant epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 13, 9622 (2023).

Khambhati, A. N. et al. Long-term brain network reorganization predicts responsive neurostimulation outcomes for focal epilepsy. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabf6588 (2021).

Jarosiewicz, B. et al. The RNS System: brain-responsive neurostimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 18, 129–138 (2021).

Ojemann, W. K. S. et al. Resting-state background features demonstrate multidien cycles in long-term EEG device recordings. Brain Stimul. 16, 1709–1718 (2023).

Grzeskowiak, C. L. et al. Seizure forecasting: patient and caregiver perspectives. Front. Neurol. 12, 717428 (2021).

Mormann, F. et al. Epileptic seizures are preceded by a decrease in synchronization. Epilepsy Res. 53, 173–185 (2003).

Maturana, M. I. et al. Critical slowing down as a biomarker for seizure susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 11, 2172 (2020).

Chang, W. C. et al. Loss of neuronal network resilience precedes seizures and determines the ictogenic nature of interictal synaptic perturbations. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1742–1752 (2018).

Schroeder, G. M. et al. Chronic intracranial EEG recordings and interictal spike rate reveal multiscale temporal modulations in seizure states. Brain Commun. 5, fcad205 (2023).

Chiang, S. et al. Evidence of state-dependence in the effectiveness of responsive neurostimulation for seizure modulation. Brain Stimul. 14, 366–375 (2021).

Anderson, D. N. et al. Closed-loop stimulation in periods with less epileptiform activity drives improved epilepsy outcomes. Brain 147, 521–531 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Seizure forecasting by high-frequency activity (80–170 Hz) in long-term continuous intracranial EEG recordings. Neurology 99, e364–e375 (2022).

Cook, M. J. et al. Prediction of seizure likelihood with a long-term, implanted seizure advisory system in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: a first-in-man study. Lancet Neurol. 12, 563–571 (2013).

Friedrichs-Maeder, C. et al. Seizure cycles under pharmacotherapy. Ann. Neurol. 95, 743–753 (2024).

RNS System Programming Manual. NeuroPace https://www.neuropace.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/neuropace-rns-system-programming-manual.pdf (2022).

Sisterson, N. D. et al. A rational approach to understanding and evaluating responsive neurostimulation. Neuroinformatics 18, 365–375 (2020).

Leguia, M. G. et al. Measuring synchrony in bio-medical timeseries. Chaos 31, 013138 (2021).

Fisher, R. A. in Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution (eds Kotz S. & Johnson, N. L.) 66–70 (Springer, 1970).

Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Springer, 2006).

Lee, Y. et al. Multicategory support vector machines. In Interface Meeting Technical Report No. 1040 (2001).

Norgeot, B. et al. Minimum information about clinical artificial intelligence modeling: the MI-CLAIM checklist. Nat. Med. 26, 1320–1324 (2020).

Acknowledgements

A.N.K. is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant no. R61 NS125568-01A1). M.O.B. is supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Grant (Eccellenza, grant no. 203339). V.R.R. is supported by an endowed professorship from the Ernest Gallo Foundation. We thank T. Proix for valuable discussions during development of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.K., M.O.B. and V.R.R. initiated the work with M.O.B. and V.R.R. supervising the work equally. A.N.K. and V.R.R. drafted the manuscript. A.N.K., E.F.C., M.O.B. and V.R.R. collected and analyzed the data. V.R.R. finalized the manuscript. All authors approved the work and take responsibility for its integrity.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

UCSF and E.F.C. have patents related to brain stimulation for neuropsychiatric disorders unrelated to this study. V.R.R. has served as a paid consultant for NeuroPace but declares no targeted funding from NeuroPace for this study. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks William Stacey, Josef Parvizi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jerome Staal, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

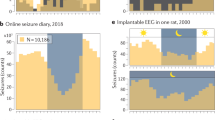

Extended Data Fig. 1 Distribution of Scheduled ECoG recordings across study cohort.

(a) Significant non-uniform distribution of Scheduled ECoGs over the multidien phases of IEA (P = 5.21 × 10−32, one-sided Rayleigh test) across participants (n = 15). Given inhomogeneous sampling of IEA phase, we used surrogate statistics and data resampling to minimize sampling bias. Bold, mean; shading, SEM. (b) Distribution of the total number of scheduled ECoG recordings sampled at four times of the day across participants (n = 15; box plots show the maximum and minimum values (whiskers), median (center line) and the 25th to 75th percentiles (box limits)). We verified that ECoG recordings are not sampled unevenly across the different times of the day (One-way ANOVA, F = 0.003, P = 0.99) across participants.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Simulated effect of interictal spiking on amplitude- and phase-based measurements of ECoG signal.

(a) Verum baseline interictal ECoG recording free of interictal spiking. (b) Measures of functional connectivity based on amplitude correlation, generalized coherence, and phase coherence. (c) Baseline recording corrupted by the addition of a single burst of interictal spikes to two channels. (d) Addition of the burst corrupted the amplitude and generalized coherence measurement as compared to baseline. No change was observed for the metric of connectivity based on phase coherence. (e) Baseline recording corrupted by the addition of an interictal spike train to two channels. (f) Addition of a spike train corrupted the amplitude and generalized coherence measurement as compared to baseline. No change was observed for the metric of connectivity based on phase coherence. Phase-based measures exhibit robust insensitivity to spike-driven amplitude shifts in the signal and may provide a more reliable estimate of connectivity in the presence of interictal spikes than amplitude correlation and generalized coherence.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Distribution of multidien IEA cycle periods across study participants.

(a) Relative power of multidien IEA cycles across different periodicities spanning 4–45 days (x-axis) and study participants (y-axis). Instantaneous phase of the multidien IEA cycle is computed based on the dominant rhythm within the broadband period of 4–45 days. Color intensity, relative spectral power across frequencies.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Individual participant distributions of hippocampal FC alongside cycles of seizure risk.

(a) Model performance (R2) of phase-encoding generalized linear model (PE-GLM) relating multidien IEA phase as a predictor of local (left, red) and long-range (right, blue) functional connectivity across participants (n = 15). True model performance is displayed in comparison to a permutation-based null distribution; bold, mean; shaded, SEM; dashed 99.9% confidence interval. IEA phase predicts functional connectivity changes across time significantly better than the permutation-based surrogate model across a broadband range of spectral frequencies for both local and long-range connections (one-sided permutation test; p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected) across participants. (b-f) Distribution of local (red) and long-range (blue) functional connectivity per study participant (y-axis) over two cycles of the multidien IEA cycle (x-axis) for (b) delta band, (c) theta band, (d) alpha band, (e) beta band, and (f) gamma band. Color intensity shows peak FC strength within the frequency band in an individual participant (purple colors indicate overlapping local and long-range connectivity). Contour lines reflect 99% confidence intervals generated by a permutation-based surrogate data generation model that preserves amplitude distributions while shuffling the temporal order of phase within the signal. Participant order sorted by hippocampal FC preference to the trough of the cycle. Consistency in the relationship between FC and IEA cycle phase is demonstrated by uniform color intensity across rows (participants) at discrete columns (cycle phases). Thick bordered boxes are colored based on functional connectivity type found to be significant at the population-level (Fig. 1e).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Distribution of spectral band power across multidien IEA cycles.

(a, top) Polar plot showing seizure likelihood (purple) predicted by phase of multidien IEA cycles (n = 15 subjects). Linearized depiction of fluctuating seizure likelihood as a function of phase over two cycles to aid visualization of continuity at cycle edges (bold, mean; shading, SEM). (a, bottom) Relative change in spectral power per frequency band (y-axis) over two multidien IEA cycles (x-axis) aggregated across participants (n = 15). There is a broadband increase in spectral power near the peak and falling phases of the multidien IEA cycle. No significant population-level effect was observed at the trough or rising phase of the multidien IEA cycle. Color intensity, spectral power effect across subjects; lines, 99% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Flowchart for training and testing FC-based seizure forecasting model.

A leave-one-patient-out model training and testing paradigm is used in this study. This ensures that seizure forecasts issued in the test participant are never based on future data from that test participant; that is, forecasts are causal. (top) In model training, all participants other than a test participant are grouped into a cohort of training participants. While leaving the test participant out, a single held-out FC-IEA map is constructed using data from all training participants. Concurrently, each Scheduled ECoG recording across training participants is extracted from the RNS System. A binary label (response variable in forecasting model) is assigned to each Scheduled ECoG recording indicating whether a seizure occurred in the 24-h period following the recording. A hippocampal FC feature set comprised of local and long-range ECoG channel pairs and multiple spectral frequency bands is measured from each Scheduled ECoG recording (see Methods); there is a 1:1 correspondence between the number of hippocampal FC feature sets and number of Scheduled ECoG recordings across training participants. Each hippocampal FC feature set is compared against the held-out FC-IEA map (see Methods) to estimate cycle phase (predictor variable in forecasting model). Probabilistic seizure forecasting model is trained using all FC-based phase estimates and binary labels of 24-h seizure occurrence. (bottom) In model testing, we identify the participant held-out from the training cohort. Each Scheduled ECoG recording is independently processed to yield the hippocampal FC feature sets. Cycle phase estimates (predictors) are computed by comparing each hippocampal FC feature set of the test participant against the fixed FC-IEA map generated during the model training step performed on the training participants. Probabilistic seizure forecasts are calculated for each Scheduled ECoG recording in the test participant by inputting FC-based phase estimates into the fixed seizure forecasting model that was constructed during the model training step. The probabilistic seizure forecasts are subsequently fed into post-hoc analyses to evaluate performance.

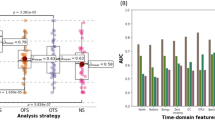

Extended Data Fig. 7 Distribution of performance measures per forecasting model.

Distributions of FC-based model performance (blue) and IEA cycle-based model performance (yellow) across participants (n = 15; box plots show the maximum and minimum values (whiskers), median (center line) and the 25th to 75th percentiles (box limits); violin shading shows kernel density) for (a) precision, (b) recall, and (c) F1 measures. There is no significant difference in precision, recall, or F1 score between the two models (two-sided paired t-test, P >= 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), suggesting that an estimate of momentary FC can forecast seizures as well as the benchmark model that uses multidien IEA phase measured over a timescale of 4–45 days as a predictor. (d) Receiver operating characteristic curve for FC-based models (blue), IEA cycle-based models (yellow), and shuffled baseline (gray) across participants (n = 15). There is no significant difference in the rate of false positives compared to the rate of true positives between the FC-based model and the cycle-based model (two-sided paired t-test, P >= 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). Thick lines, mean; shading, SEM; dashed line, unity line.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical Source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khambhati, A.N., Chang, E.F., Baud, M.O. et al. Hippocampal network activity forecasts epileptic seizures. Nat Med 30, 2787–2790 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03149-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03149-6

This article is cited by

-

Soft sonocapacitor with topologically integrated piezodielectric nanospheres enables wireless epidural closed-loop neuromodulation

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Mechanistic insights into the interaction between epilepsy and sleep

Nature Reviews Neurology (2025)

-

Latent periodicity in epilepsy

Clinical Epileptology (2024)