Abstract

The brain barrier system, including the choroid plexus, meninges and brain vasculature, regulates substrate transport and maintains differential protein concentrations between blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Aging and neurodegeneration disrupt brain barrier function, but proteomic studies of the effects on blood–CSF protein balance are limited. Here we used SomaScan proteomics to characterize paired CSF and plasma samples from 2,171 healthy or cognitively impaired older individuals from multiple cohorts, including the Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium. We identified proteins with correlated CSF and plasma levels that are produced primarily outside the brain and are enriched for structural domains that may enable their transport across brain barriers. CSF to plasma ratios of 848 proteins increased with aging in healthy control individuals, including complement and coagulation proteins, chemokines and proteins linked to neurodegeneration, whereas 64 protein ratios decreased with age, suggesting substrate-specific barrier regulation. Notably, elevated CSF to plasma ratios of peripherally derived or vascular-associated proteins, including DCUN1D1, MFGE8 and VEGFA, were associated with preserved cognitive function. Genome-wide association studies identified genetic loci associated with CSF to plasma ratios of 241 proteins, many of which have known disease associations, including FCN2, the collagen-like domain of which may facilitate blood–CSF transport. Overall, this work provides molecular insight into the human brain barrier system and its disruption with age and disease, with implications for the development of brain-permeable therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Aging is one of the largest risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease1, which represent a substantial burden for patients, their families and healthcare systems. Even in the absence of disease, normal brain aging leads to declines in cognitive function across multiple domains2. Increased understanding of aging and neurodegeneration-related processes in the brain is crucial for the development of effective therapeutic interventions for these conditions.

Brain barrier dysfunction has been widely observed in both the aged brain3,4 and neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease5,6, Parkinson’s disease7 and frontotemporal dementia (FTD)8. The system of barriers separating the blood from the brain is complex and dynamic, including a variety of anatomical and cellular components9. The most well studied is the vascular blood–brain barrier (BBB), which includes brain endothelial cells, pericytes, smooth muscle cells and astrocytes. In addition, epithelial cells of the choroid plexus and meninges form the blood–CSF barrier, with the most active transport to CSF likely occurring in the choroid plexus. These barriers contain tight junctions to prevent the unregulated flow of blood products into the brain and express a variety of transporters to promote the exchange of desired substrates.

In humans, brain barrier dysfunction can be assessed postmortem by staining brain sections for specific blood proteins; in vivo assessments include the use of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to calculate the region-specific permeability (Ktrans) to an exogenously administered gadolinium tracer or the albumin quotient (Qalb), a ratio of CSF albumin levels divided by plasma albumin levels. However, these methods quantify permeability only to a single tracer or protein, leaving protein-specific differences unclear. In addition, brain barrier leakiness, as assessed by traditional methods, has been typically assumed to be harmful as a result of its association with disease, but brain barriers are incredibly dynamic and seem to exhibit remarkable permeability to plasma proteins in the healthy young brain. For example, in young mice, circulatory proteins are broadly taken up into the brain parenchyma10 and, in humans, liver proteins such as albumin, α2-macroglobulin and haptoglobin are abundantly detected in CSF11, whereas hundreds of proteins produced uniquely in the brain can be detected in blood12. These findings support complex bidirectional transport between blood and brain, but aging and disease-related changes in brain transport are still unclear for many proteins and there may be substrate-specific differences in functional effects.

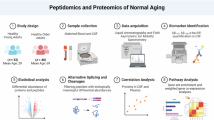

To understand how CSF–plasma protein balance changes with aging and disease, we utilized SomaScan proteomics on paired human CSF and plasma samples from 2,171 individuals across three cohorts: the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Knight-ADRC), Stanford and the Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC). We identified proteins primarily produced outside the brain and examined correlations between CSF and plasma protein levels to identify candidates that may be actively transported from the blood to the CSF, using enrichment analyses to identify relevant protein structural domains. We calculated CSF to plasma ratios (CSF level divided by plasma level) for each protein, providing an individualized readout of CSF–plasma protein balance, and assessed associations of these ratios with age, sex and cognitive impairment. Last, we performed genome-wide association studies (GWASs) to identify genetic variants associated with CSF to plasma ratios and examined the effects of variants on protein structure.

Results

To understand the relationships between CSF and plasma protein levels, we used the SomaScan platform to perform proteomics on paired CSF and plasma samples from 2,171 people, including 931 healthy controls and 1,240 participants with neurodegenerative disease and cognitive impairment (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Some 2,304 proteins were robustly detected in both CSF and plasma (Methods) and were included in analyses for the present study (Supplementary Table 2). Proteins in the CSF could either be produced locally in the brain before secretion into the CSF or be synthesized elsewhere in the body, secreted into the blood and transported across brain barriers into the CSF (Fig. 1a). To understand the likely source of the proteins that we detected in the CSF, we annotated each protein as being predominantly derived from either the central nervous system (CNS) or the peripheral organs or expressed in both places, using human bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project from organs across the body (Methods). Strikingly, 742 proteins with expression in peripheral organs were detected in healthy human CSF (Fig. 1b).

a, Schematic showing routes for proteins to reach the CSF. Proteins can be locally produced either in the brain or in peripheral organs, secreted to the blood and transported into the CSF across the brain barrier system. b, Protein source annotation for the 2,304 proteins robustly detected in CSF. Fourfold enrichment of bulk GTEx RNA expression in the relevant tissues was required for annotation as CNS derived or peripheral organ derived. c,d, Histogram of Pearson’s coefficients for correlations between CSF and plasma levels in the Stanford cohort (n = 304) for CNS proteins (c) and peripheral proteins (d). e, Bar plot showing the percentage of proteins with positive CSF–plasma correlations (Pearson’s r > 0.2) by protein source. Two-proportion z-test P values: P = 1.2 × 10−33 (peripheral versus both), P = 5.5 × 10−12 (peripheral versus CNS) and P = 9.3 × 10−3 (both versus CNS). f, Correlation between CSF and plasma leptin levels. g, Schematic showing that leptin is secreted by adipose tissue and uses leptin receptor-mediated transport to cross the BBB. h, Enrichment for UniProt domains within the set of peripheral proteins with correlated CSF and plasma levels (r < 0.2). CP, choroid plexus; Ig, immunoglobulin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LepR, leptin receptor.

To characterize the relationships between CSF and plasma protein levels across the proteome, we calculated the correlation between CSF and plasma levels for each protein. Pearson’s correlations were performed in the Stanford cohort (n = 304) and replicated in the Knight-ADRC and GNPC cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Table 3). Most CSF–plasma correlations were positive and relatively weak. Peripherally derived proteins had significantly more positive correlations than those produced in the CNS (Fig. 1c–e). It is interesting that 61 of the 742 peripheral proteins detected in CSF had very strong CSF–plasma correlations (r > 0.7). One reason for these strong correlations could be that CSF levels of these peripherally derived proteins result from their active transport across brain barriers at levels proportional to the plasma concentration. Supporting this hypothesis, one of the top peripheral proteins with strong CSF–plasma correlation was leptin (Pearson’s r = 0.80) (Fig. 1f), which is produced by adipose tissue and known to be actively transported from the blood into the brain by the leptin receptor (Fig. 1g).

As a protein’s physical properties affect its transport across brain barriers13, we examined how size, charge and structure of peripherally derived proteins related to their CSF–plasma correlations. There was no significant relationship between a protein’s CSF–plasma correlation coefficient and its mass (Pearson’s r = −0.01) or charge (Pearson’s r = 0.02) (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d), suggesting that more fine-grained structural features may be important in regulating transport across the blood–CSF barrier. We performed enrichment analysis for structural protein domains and identified multiple protein domains that were enriched in proteins with positive CSF–plasma correlations (Fig. 1h). Notably, correlated proteins were enriched for Kunitz inhibitor domains, which have previously been explored as a therapeutic brain shuttle candidate14,15, indicating that our approach can pick up domains that facilitate brain barrier transport. Also enriched were Sushi domains, which are present on many proteins involved in the complement cascade, and the C-type lectin domain, which could facilitate interactions with the layer of sugars in the vascular lumen that form the brain endothelial glycocalyx. These domains could represent candidates for the engineering of new brain transport shuttles to deliver therapeutic cargo from the plasma to the CSF.

CSF–plasma protein balance changes with age

Although correlations provide a measure of the strength and direction of the population-level relationship between CSF and plasma protein levels, we also wanted to examine how these CSF–plasma relationships vary with participant-level individual traits, such as age or disease status, while controlling for other covariates. To do this, we calculated the ratio of CSF protein level divided by plasma protein level for each protein in each person, providing an individualized measure of CSF–plasma protein balance. Many factors could be responsible for differences in CSF to plasma protein ratios, including changes in synthesis or degradation in either fluid compartment, but a main motivation for the present study was the known impact of age and neurodegenerative disease on brain barrier function—we hypothesized that ratios of some proteins may provide a readout of these barrier changes (Fig. 2a). For proteins that are primarily being made in the periphery, changes in ratios with age or disease may represent changes in these proteins’ transport across the system of brain barriers, because the levels of these proteins in the CSF likely originate from the plasma. Indeed, the ratio of CSF and serum concentrations of albumin is used clinically as a measure of BBB permeability in neuroinflammatory and degenerative conditions16,17,18. On the other hand, for proteins primarily made in the brain, their CSF to plasma ratios may indicate the rate of protein clearance from the CSF to the blood.

a, CSF to plasma ratios calculated for 2,304 proteins by dividing CSF levels by plasma levels. Associations between CSF to plasma ratios and individual traits, including age, sex and cognitive impairment, were examined. b, Volcano plot showing associations between CSF to plasma ratios and age, assessed using fixed-effects meta-analysis of linear regression results in HC participants from the Stanford (n = 200) and Knight-ADRC (n = 180) cohorts, with sex as a covariate. The x axis shows the estimated age coefficient β as a fraction of the mean CSF to plasma ratio and the y axis the Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected q value. c, Bar plot showing the percentage of proteins up- and downregulated with age (q < 0.05), by protein source. The two-sided binomial test of equal probability of up- or downregulation was used: P = 1.4 × 10−175. d, Correlation of signed log10(P) significance values per protein from the Knight-ADRC/Stanford meta-analysis (x axis, n = 380) versus GNPC (y axis, n = 551); Pearson’s r = 0.76. e, Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment for proteins with ratios that increase with age. f, Ratios were z-scored and nonlinear aging trajectories were estimated using LOWESS. LOWESS estimates across ages are displayed in the heatmap. Red shows peripheral proteins, blue CNS proteins and purple proteins expressed in both. g, Box plot showing log10-transformed protein mass for peripheral proteins with CSF to plasma ratios upregulated, downregulated or unchanged with age. Unchanged versus up: P = 0.019, two-sided Tukey’s post-hoc test. The center line represents the median, the box limits the upper and lower quartiles and the whiskers the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR) from the box limits. h, Box plot, as in g, showing protein charge at pH 7.4 for peripheral proteins with ratios that were upregulated, downregulated or unchanged with age. i, Enrichment for UniProt domains within the set of age-upregulated peripheral proteins.

To understand how CSF to plasma protein ratios change during healthy aging, we examined the linear association between each of the 2,304 protein ratios and age, while controlling for sex (Fig. 2b). Only participants who were cognitively unimpaired and free from neurodegenerative disease diagnoses were included in aging analyses (Supplementary Table 4). Discovery analysis was performed in the Knight-ADRC (n = 180) and Stanford (n = 200) cohorts and cohort-level results were combined through meta-analysis using fixed-effect models (Supplementary Table 5). Significantly more proteins had CSF to plasma ratios that increased rather than decreased with age (Fig. 2c), including 295 peripherally derived proteins and 41 CNS-derived proteins, as expected owing to the increased leakiness of the brain barriers with age as well as age-related decline in CSF flow and protein clearance. These results were replicated in the control participants from the GNPC cohort (n = 551) with strong concordance (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3). Aging coefficients for CSF and plasma protein levels alone are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. Notably, 54 proteins with CSF to plasma ratios that changed with age were not significantly changed in either the CSF or the plasma alone, illustrating that ratio analysis implicates new proteins in the aging process (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Proteins with ratios that increased with age included those related to coagulation, such as fibrinogen, which has been shown to leak across the BBB in Alzheimer’s disease and contribute to harmful neuroinflammation6. Ratios of many complement proteins, including complement factor D and complement component 7, also increased with age. Proteins with ratios increasing with age were further enriched for localization to both the extracellular space and the extracellular vesicles, suggesting that proteins may be transported into the CSF either as freely soluble secreted proteins or enclosed in vesicles or exosomes (Fig. 2e).

CSF to plasma ratios of various chemokines also increased with age, possibly contributing to increased recruitment of immune cells into the aged CSF. In addition, proteins with CSF levels that had previously been identified as biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease, including neurofilament light chain (NEFL) and 14-3-3gamma (YWHAG), also had increased CSF to plasma ratios with aging, highlighting similarities between aging and disease processes. Not all protein ratios increased with age; 64 protein ratios decreased with age, including 25 peripheral proteins, highlighting the substrate-specific changes occurring at the brain barriers with age and the importance of examining barrier function at the individual substrate level. Aging trajectories for ratios of interest were estimated using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS; Fig. 2f).

We next examined structural characteristics of the peripherally derived proteins with ratios that changed with age. Proteins with ratios that increased with age were slightly larger than proteins that did not (Fig. 2g). There was no association between protein charge and ratio changes with age (Fig. 2h). It is interesting that proteins with ratios that increased with age were enriched for specific protein domains (Fig. 2i), suggesting that there is not only just a structural breakdown of brain barriers with aging, but also possibly an increase in regulated transport of specific subsets of proteins, potentially mediated by interactions between these domains and specific receptors at the brain barrier. For example, the Gla domain facilitates interactions between proteins and phospholipid membranes19 and has already been shown to be essential for the uptake of protein kinase C across the BBB20; Gla domain-containing proteins with ratios that increase with age include protein kinase C and coagulation factors VII, IX and X. Multiple domains enriched in the age-upregulated ratio group were also enriched in proteins with correlated CSF and plasma levels, including Sushi domains, immunoglobulin-like domains and the fibrinogen C-terminal domain, providing further evidence for a potential role in brain transport.

To further understand the mechanism by which CSF to plasma ratios increase with age, we looked at the association between ratios and markers of brain barrier permeability, namely CSF concentrations of PDGFRB, a marker of pericyte dysfunction that has been shown to associate with leakiness of the BBB3,21, and TFRC, a key receptor involved in transcytosis of transferrin22, with CSF concentrations that may reflect transcytosis levels. Ratios of 473 and 526 proteins were positively associated with CSF PDGFRB and TFRC, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 5a–d), including 32% (PDGFRB) and 35% (TFRC) of proteins with ratios that increased with age (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Proteins with ratios associated with PDGRFB versus TFRC were enriched for specific protein domains (Extended Data Fig. 5h,i), further emphasizing that barrier permeability to groups of proteins may be modulated by distinct biological mechanisms.

Sex effects on CSF to plasma protein ratios

Next, we examined how CSF to plasma ratios differ between men and women in healthy control (HC) participants, with age as a covariate (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 6). Overall, 648 protein ratios were affected by sex, with 296 protein ratios increased in women and 352 in men (Fig. 3b). Peripheral protein ratios were significantly increased in men compared with women (Fig. 3b), in accordance with imaging-based results showing increased permeability of the male BBB in older populations23,24.

a, Volcano plot showing associations between CSF to plasma ratios and sex in HC participants. Results are from a fixed-effect meta-analysis of linear regression results in HC participants from the Stanford (n = 200) and Knight-ADRC (n = 180) cohorts, with age as a covariate. The x axis shows log2(fold-change), with positive values representing higher ratios in men. The y axis shows the Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected q value. b, Bar plot showing the percentage of proteins with ratios that were significantly higher in either sex (q < 0.05), by protein source. Two-sided binomial test for peripheral proteins: P = 5.9 × 10−21. c,d, Box plots showing leptin (c) and adiponectin (d) CSF to plasma ratios by sex. The center line represents the median, the box limits the upper and lower quartiles and the whiskers the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× the IQR from the box limits. Two-sided P values from fixed-effect meta-analysis of linear regression results: leptin, P = 4.3 × 10−9; adiponectin, P = 1.0 × 10−11. e, Venn diagram showing the overlap of peripheral proteins significantly (q < 0.05) upregulated in men, in women, and with age. f, GO pathway enrichment for proteins with CSF to plasma ratios that increased with age and were higher in men than women.

Peripheral proteins with ratios that were increased in men included adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin, which are secreted by adipose tissue and transported into the brain, where they modulate energy balance and feeding behavior25,26. Increased permeability of the male BBB to these hormones could trigger a stronger central response to elevated plasma adipokine levels; as women generally have higher body fat levels, differences in adipokine transport may help maintain effective regulation of adiposity in each sex. Impaired blood-to-brain transport of adipokines may also contribute to metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes; for example, CNS leptin signaling is known to enhance insulin sensitivity and regulate glucose metabolism27. It is interesting that leptin and adiponectin ratios had opposing relationships with obesity; the leptin CSF to plasma ratio significantly decreased with body mass index (BMI) (Extended Data Fig. 6b), whereas the adiponectin ratio significantly increased with BMI (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Importantly, the sex differences in leptin and adiponectin ratios remained highly significant after further adjusting for BMI (leptin, P = 5.6 × 10−7; adiponectin, P = 5.7 × 10−8).

Proteins with CSF to plasma ratios upregulated in men also showed notable overlap with the proteins that had ratios upregulated with age (Fig. 3e). These proteins were enriched for pathways including defense and stress responses, coagulation, hemostasis and wound healing (Fig. 3f). Linear modeling of the associations between ratios and aging split by sex revealed strong concordance between aging effects in each sex (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e). Ratios of coagulation proteins, such as kininogen and coagulation factor X, increase with age at a similar rate in both sexes, and men across all ages have a higher baseline CSF to plasma ratio of these proteins compared with women (Extended Data Fig. 6f,g). The functional impact of the potential increased permeability of the male brain barriers to coagulation and stress response proteins will be interesting to explore in future studies.

Cognitive impairment and CSF to plasma ratios

To understand how relationships between CSF and plasma protein levels change with cognitive impairment, we used linear modeling to examine the associations between CSF to plasma ratios and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score in 1,280 individuals from the GNPC (Supplementary Table 7), controlling for age and sex. All individuals with MMSE scores available were from GNPC contributor Q. We identified 160 proteins with ratios that were significantly associated with MMSE scores, including 35 peripherally derived proteins (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 8). Most (71%) of proteins with ratios significantly associated with cognitive impairment also had concordant significant associations in the CSF alone (Extended Data Fig. 7b). As previous studies have profiled proteomic changes in CSF with neurodegeneration28,29, we focused on ratios of the 742 peripherally derived proteins to provide insight into brain barrier function.

a, Volcano plot showing associations between CSF to plasma ratios of peripherally derived proteins and MMSE scores in GNPC cohort Q (n = 1,280), assessed by linear regression of ratio by MMSE score with age and sex as covariates. The x axis shows MMSE coefficient β as a fraction of the mean CSF to plasma ratio. Although lower MMSE scores indicate more severe cognitive impairment, the plotted effect size was flipped such that positive effect sizes indicate that the ratio increases with cognitive impairment. The y axis shows the Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected q value. b, Bar plot showing the number of CSF to plasma ratios, the up- or downregulation of which was associated with cognitive (cog.) impairment (q < 0.05), by protein source. c, Overlap among peripheral proteins with ratios significantly (q < 0.05) associated with both cognitive impairment and healthy aging. For the association with age, significant associations were required in both the GNPC aging analysis and Knight-ADRC/Stanford aging meta-analysis. N/A, no overlap. d, Box plot showing the association of the fibrinogen CSF to plasma ratio with cognitive impairment (MMSE) in GNPC cohort Q (n = 1,280). Cutoffs for cognitive impairment visualization are: none: MMSE > 25; mild: MMSE 21–25; moderate (Mod): MMSE 11–20; and severe (Sev): MMSE < 11. The P value refers to the significance of the MMSE coefficient from linear regression of the fibrinogen ratio by MMSE score with age and sex as covariates and is two sided. e, Scatterplot showing the association of the fibrinogen CSF to plasma ratio with age in healthy participants in the GNPC cohort (n = 551). The P value refers to the significance of the age coefficient from linear regression of the fibrinogen ratio by age with sex and contributor code as covariates, and is two sided. f,h,j, Box plots showing the associations of CSF to plasma ratios of DCUN1D1 (f), MFGE8 (h) and VEGFA (j) with cognitive impairment in the indicated cohorts. Cognitive impairment was assessed by MMSE score in GNPC cohort Q (n = 1,280), MoCA score in GNPC cohort N (n = 240) and CDR-global score in Stanford (n = 238) and Knight-ADRC (n = 243) cohorts. The P values refer to the significance of the cognitive score coefficient from linear regression of ratio by cognitive score with age and sex as covariates, and are two sided. MoCA cutoffs for cognitive impairment visualization are: none: MoCA > 25; mild: MoCA = 18–25; moderate: MoCA = 10–17; and severe: MoCA < 10. The center line represents the median, the box limits the upper and lower quartiles and the whiskers the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× the IQR from the box limits. g,i,k, Forest plots showing the associations of CSF to plasma ratios of DCUN1D1 (g), MFGE8 (i) and VEGFA (k) with cognitive impairment in the indicated cohorts. Cognitive test scores were z-score normalized before analysis. GNPC cohort Q: n = 1,280; GNPC cohort N: n = 240; Stanford: n = 238; and Knight-ADRC: n = 243. The red squares represent the cognitive test score coefficient β from linear regression as a fraction of the mean CSF to plasma ratio. The bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The diamonds represent the mean normalized coefficient estimate (center) and 95% CI (edges) from a crosscohort, random-effects meta-analysis, with two-sided P values displayed.

Surprisingly, unlike the aging-associated ratios, we observed no widespread upregulation of CSF to plasma ratios with cognitive impairment; although ratios of 12 peripherally derived proteins were upregulated with cognitive impairment, 23 peripheral protein ratios were downregulated with cognitive impairment (Fig. 4b). Ten peripherally derived proteins had concordant associations with age and cognitive impairment (Fig. 4c), supporting the idea that some age-related barrier changes may be detrimental to cognitive function. Notably, the CSF to plasma ratio of fibrinogen increased with both severity of cognitive impairment (Fig. 4d) and healthy aging in the GNPC cohort (Fig. 4e), in agreement with previous studies showing that leakage of fibrinogen through the BBB promotes inflammation and neuronal damage in neurodegenerative diseases30.

The peripheral protein most significantly associated with cognitive impairment was DCUN1D1, which is involved in neddylation and protein degradation31. The DCUN1D1 ratio was higher in cognitively normal participants and decreased with cognitive impairment, and this result was replicated in three independent cohorts with two additional cognitive tests, using Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores in the GNPC participants from contributor N (n = 240) and CDR scores in the Stanford (n = 238) and Knight-ADRC (n = 243) cohorts (Fig. 4f,g). The decline in the DCUN1D1 ratio with cognitive impairment was also observed when cognitively impaired participants from GNPC cohort Q were limited to those with a clinical diagnosis of mild or subjective cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease (n = 937; Extended Data Fig. 7c). It is interesting that the DCUN1D1 ratio also significantly increased with age in the HCs from the Stanford and Knight-ADRC cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 8), suggesting that increased blood-to-CSF transport of DCUN1D1 with aging may confer some protection against cognitive decline. In addition, vascular-related proteins MFGE8 (lactadherin) and VEGFA showed robust decreases in the CSF to plasma ratio with cognitive impairment across cohorts and cognitive tests (Fig. 4h–k and Extended Data Fig. 7). MFGE8 is a secreted glycoprotein originally identified as a component of milk fat globules; it is a precursor for medin, which accumulates in the vascular wall with aging and colocalizes with vascular amyloid deposits in Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy32,33. Lower CSF to plasma ratios of MFGE8 in cognitively impaired participants could indicate higher levels of vascular medin aggregation, which may tend to trap additional MFGE8 rather than allowing it to cross through to the CSF; further studies will be needed to clarify the relationship of the MFGE8 ratio with vascular amyloid phenotypes.

The CSF to plasma ratio of the pro-angiogenic factor VEGFA is also consistently decreased with cognitive impairment; numerous studies have shown dysregulation of VEGFA levels in the CSF, blood and brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, but the directionality of these effects has been disputed between studies34,35,36,37,38. The consistent downregulation of the VEGFA CSF to plasma ratio with cognitive impairment across >2,000 people suggests that balance of VEGFA localization to CSF versus blood may be key to its functionality in disease. Intriguingly, MFGE8 is required for VEGF-dependent angiogenesis39, suggesting that the declines in these ratios may be mechanistically linked and motivating further studies of the mechanistic impacts of these proteins on angiogenesis and cognitive decline.

Genetic variation associated with CSF to plasma ratios

Finally, we examined how CSF to plasma protein ratios associate with genetic variation (Fig. 5a). Using genetic data from 208 individuals in the Stanford cohort and 243 individuals in the Knight-ADRC cohort (Supplementary Table 9), we performed GWASs to identify variants linked to each of 2,304 protein ratios. We identified 320 quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with CSF to plasma ratios of 241 proteins, using a stringent genome-wide and multiple comparison-corrected significance threshold of P < 2.17 × 10−11 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 10). Most proteins (95%) had only one significantly associated QTL. Of the proteins with significant associations, 127 out of 241 had a cis association whereas 114 out of 241 had only a trans association (Fig. 5c). Peripherally derived proteins were enriched within the proteins with cis mutations (53%) compared with those with trans mutations (40%). The correlation of effect sizes between the analyses done in the Stanford and Knight-ADRC cohorts revealed strong concordance between studies (Extended Data Fig. 9). A total of 91 proteins with a ratio QTL also had their ratio change with age. In addition, 13 proteins with a ratio QTL had ratios associated with cognitive impairment, including 3 proteins, NEFL, S100A13 and CHFR, with ratios associated with the APOE locus (Extended Data Fig. 9).

a, Schematic of the GWAS study design. b, Combined Manhattan plot for QTL associations between genetic variants and 2,304 CSF to plasma ratios. The log10(P) were calculated from fixed-effect meta-analysis of linear regression results in the Stanford (n = 208) and Knight-ADRC (n = 243) cohorts. The top 20 most significant associations are labeled with the associated CSF to plasma ratio protein; associations in cis are indicated in bold and those in trans are in italic. c, Bar plot showing the number of proteins with cis or trans QTLs. The colors indicate the protein source. d, Bar plot showing colocalization of QTLs with previously identified CSF and plasma pQTLs. e, Dot plot showing disease enrichment for DisGeNet disease–protein associations within the set of 83 proteins with a unique QTL associated with their CSF to plasma ratio. The log10(q) (x axis) were derived from Fisher’s exact test with the Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. f, Bar plot showing the source of proteins with a significant cis-QTL that is predicted to have an impact on protein structure. g, Box plot showing CSF to plasma ratios of TCN2 stratified by rs1801198 genotype (C>G). The displayed P value is from the fixed-effect meta-analysis (n = 451) using linear regression to assess the association between TCN2 ratio and genotype, and is two sided. For all box plots, the center line represents the median, the box limits the upper and lower quartiles and the whiskers the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× the IQR from the box limits. h, Correlation between CSF and plasma TCN2 levels, stratified by genotype. The r and P values were calculated using Pearson’s correlations. The estimated regression line with 95% CIs is plotted for each genotype. i, Schematic of the hypothesized effects of TCN2 genotype on TCN2 transport into the brain. j, Box plot showing CSF to plasma ratios of FCN2, stratified by rs3128624 genotype (A>G). The displayed P value is from the fixed-effect meta-analysis (n = 451) using linear regression to assess the association between FCN2 ratio and genotype, and is two sided. k, Box plot showing transcript levels for FCN2 isoforms, stratified by rs3128624 genotype (A>G) in liver bulk RNA-seq data from the GTEx database (n = 208). The P values were derived from linear regression of inverse normal-transformed expression counts and are two sided: FCN2-201, P = 2.5 × 10−26; FCN2-202, P = 0.009. l, AlphaFold structural modeling for trimers of FCN2-201 and FCN2-202. The structures are colored by the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT), which reflects the confidence in the local structure prediction. m, Schematic of the hypothesized effects of FCN2 genotype on FCN2 transport and brain health. TPM, transcripts per kilobase million.

We compared our ratio QTLs to previously identified plasma40 and CSF41 pQTLs to identify new associations that could be found using ratios (Fig. 5d). Notably, 83 loci were unique to our ratio analysis; these loci did not colocalize (posterior probability of hypothesis 4 (PP.H4) < 0.8) with previously identified loci for the same protein in either CSF or plasma (Fig. 5d). SIRPB1, TAPBPL and FCN2 had the most highly significant unique ratio QTLs (Extended Data Fig. 9). Proteins with a unique ratio locus have previously been linked to various diseases; we used DisGeNet42 to perform enrichment analysis for disease–gene associations and identified enrichment for various neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, stroke and brain cancers (Fig. 5e).

Of the 127 cis ratio QTLs, 56 included a protein-coding or splice-site mutation (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 11), suggesting a particular residue or region that may be important for protein uptake across the blood–CSF barrier. A notable example is transcobalamin-2 (TCN2), a secreted protein that binds to circulating vitamin B12 in the blood and utilizes the CD320 receptor to facilitate vitamin B12 uptake into the brain43. There is a 2.3-fold decrease in median TCN2 ratio associated with the cis-SNP rs1801198, which involves a C-to-G substitution at nucleotide 776, resulting in a Pro259Arg amino acid substitution that is linked with vitamin B12 deficiency44. In addition, individuals carrying the C genotype show a significant correlation between CSF and plasma levels of TCN2, likely indicating its active transport across the brain barriers, but this correlation is lost in those homozygous for the alternative allele, suggesting impaired transport to the CSF45 (Fig. 5h,i). Although we did not find the TCN2 ratio to be associated with cognitive impairment in our neurodegenerative disease-focused cohorts, impaired transport of vitamin B12 into the brain as mediated by TCN2 may be associated with the neurological symptoms commonly observed with vitamin B12 deficiency, including memory loss and confusion.

One of the strongest unique ratio QTL associations was for ficolin-2 (FCN2), a secreted glycoprotein produced by the liver that activates the lectin arm of the complement pathway by tagging apoptotic cells for phagocytosis46. Homozygosity for the alternative G genotype at the rs3128624 variant results in a 2.3-fold increase in median FCN2 CSF to plasma ratio relative to the reference A genotype (P = 6.0 × 10−43; Fig. 5j), suggesting increased transport of FCN2 into the brain. Notably, this variant is found within a polypyrimidine splice tract in the second intron of FCN2 and is strongly associated with alternative splicing of FCN2 in the liver, with an 8.8× increase in levels of the full-length transcript (FCN2-201) between homozygotes with the reference and the alternative allele (Fig. 5k). The alternative transcript, FCN2-202, which is the dominant transcript for the reference C genotype, lacks exon 2, which encodes a portion of the collagen-like domain of the protein. AlphaFold was used to model these isoform effects on the structure of FCN2, which usually exists as a trimer. Exclusion of exon 2 markedly disrupts the collagen-like triple helix (Fig. 5l), whereas the structure of the fibrinogen C-terminal domain remains unperturbed (Extended Data Fig. 10), suggesting that the collagen helix may play a crucial role in regulating FCN2 uptake across the brain barriers. Intriguingly, collagen-like domains are enriched in proteins with correlated CSF plasma levels (Fig. 1h), including FCN2 (Extended Data Fig. 10), suggesting that this domain may have a more general importance in blood–CSF transport and motivating further investigation into its application for the delivery of therapeutic molecules to the brain.

FCN2 has previously been linked to various neurological diseases: plasma levels have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease47 and, notably, higher CSF or brain levels are linked to worse outcomes in multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury, including higher disability and mortality rates48,49,50,51. Although this locus has not been implicated in GWAS analyses of the prevalence of these diseases, a genetic predisposition to increased brain transport of FCN2 could contribute to worse outcomes in these neuroinflammatory diseases (Fig. 5m); well-powered GWASs of outcome metrics are lacking. Future focused studies should confirm whether the FCN2 ratio QTL is associated with a worse prognosis in neuroinflammatory disease.

Discussion

Although prior well-powered studies have examined CSF and plasma proteomic levels separately to understand the effects of age and disease on these individual fluids, this work represents one of the largest-scale characterizations of changes in the relationships between human CSF and plasma protein levels, analyzing 2,304 proteins in paired samples from 2,171 individuals. Our findings demonstrate that the balance of CSF and plasma protein levels varies with aging, sex, cognitive impairment and genetic factors. The most prominent changes in CSF to plasma ratios occur with healthy aging, with 40% of peripheral proteins, 34% of CNS proteins and 35% of proteins expressed in both compartments having an increased CSF to plasma ratio with age. The strong trend toward increased rather than decreased CSF to plasma ratios with age is consistent with both the increased brain barrier permeability and decreased glymphatic clearance that is known to occur with aging3,4,52,53. Although a slightly larger fraction of peripheral proteins has increased ratios, perhaps related to brain barrier dysfunction, the similarly large fraction of brain-derived proteins with increased ratios suggests that declining clearance of CSF proteins with age may play a more impactful role in defining the aging CSF proteome.

We did not find widespread increases in CSF to plasma ratios of peripherally derived proteins with cognitive impairment, which is somewhat surprising given the vast literature linking brain barrier leakage to neurodegenerative disease. However, most prior work has focused on dysfunction at the vascular BBB; although CSF to plasma ratios could read out vascular barrier dysfunction through the clearance to CSF of proteins that penetrate through the vasculature, it is likely a more direct readout of blood–CSF barrier transport through the choroid plexus epithelium. We found that the CSF to plasma ratio of fibrinogen, which has been previously identified to leak through diseased brain vasculature, was associated with cognitive impairment; however, further studies are needed to confirm whether this increased ratio reflects the previously observed increase in vascular transport or additional transport of fibrinogen directly through the blood–CSF barrier. Brain endothelial cells and choroid plexus epithelial cells share many barrier properties, including tight junctions, and the expression of many of the same receptors utilized for transcytosis54, but our findings suggest that these barriers may be regulated differently in neurodegenerative disease.

Research has also challenged the idea that increased brain barrier permeability is necessarily damaging, presenting the blood–brain interface as a dynamic milieu in which the delivery of specific peripherally derived proteins into the brain is important for healthy brain function10,55. Here we show a striking upregulation of peripheral protein ratios in men (25%) compared with women (6%), including many of the proteins with ratios that increase with age, consistent with previous reports of increased permeability of the male brain barriers23,24,56,57. Given the lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease in men58, increased transport of some of these proteins into the brain may have a protective effect during brain aging. Also, consistent with this idea, we found that ratios of certain peripherally derived proteins, such as DCUN1D1, MFGE8 and VEGFA, were increased in cognitively healthy participants compared with those who are cognitively impaired. These proteins could be targets for therapeutic interventions in dementia.

Protein QTL studies have been transformative in linking genetic variants to their functional outcomes. Here we performed, to our knowledge, one of the first GWASs to identify variants associated with CSF to plasma protein ratios, potential genetic regulators of brain barrier function. We identified 56 loci predicted to modify the structure of their associated ratio protein, including loci for TCN2 and FCN2, providing information on structural elements important for brain barrier uptake. Although our sample size was somewhat limited relative to prior GWASs of CSF and plasma protein levels alone, we identified 83 unique loci associated with CSF to plasma ratios that do not colocalize with previously identified CSF or plasma pQTLs. Future studies with increased sample size may have additional power to detect variants that affect the CSF to plasma ratios of multiple proteins in trans, which could point to new BBB receptors or other master regulators of brain barrier function.

A strength of the present study is the ability to directly study human brain barrier function without the use of any model system. Numerous differences have been observed between human brain barriers and animal models59,60 and the enormous cellular and anatomical complexity of the brain barrier system has proved difficult to effectively model in vitro61. Accordingly, delivery of therapeutic cargo to the human brain remains a critical challenge. Programs using antibodies against BBB receptors like the transferrin receptor show promise for drug delivery, reaching delivery rates of up to approximately 1% (ref. 62). However, many plasma proteins show even greater penetrance of the BBB10, illustrating that shuttles can be further optimized. In addition, anatomical and cellular localization of therapeutic cargo can be affected by the choice of shuttle63; as desired localization may differ across conditions, the development of new shuttle candidates, like the collagen-like domain identified in the present study, may help to optimize delivery across disease contexts. Direct study of the human brain barrier system and its natural ligands, plasma proteins, represents a promising avenue for improving brain therapeutic delivery.

A caveat of our study is that we cannot conclusively determine the molecular underpinnings of changes in each CSF to plasma protein ratio. Protein levels in blood or CSF might change as a result of either altered transport at the blood–brain or blood–CSF barrier or changes in protein stability, synthesis or degradation. These variables will have to be assessed for each protein, although such studies are currently not feasible in humans. Future longitudinal, rather than cross-sectional, studies will also be useful to confirm changes in CSF to plasma ratios with age. In addition, our analyses were limited to proteins measured by the SomaScan 5K assay; other methods such as the SomaScan 11K assay or unbiased mass spectrometry may uncover additional proteins with CSF to plasma ratios associated with age, sex, genetics or cognitive impairment.

Future research building on the present study could utilize CSF to plasma proteomic ratios to investigate brain barrier function across a wider range of neurological and psychiatric disorders, helping to uncover disease- and substrate-specific changes in barrier permeability and protein turnover. In addition, examining protein ratios between different compartments, such as the interstitial fluid or lymphatic drainage, could provide further insight into other modes of protein transport and clearance in the brain. Ultimately, this work lays the foundation for a deeper understanding of the dynamic interactions between the brain and the peripheral circulation, offering new directions for biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

Methods

Participants

Stanford (ADRC, SAMS, BPD, SCMD)

Plasma and CSF collection, processing and storage for all Stanford cohorts were performed using a single standard operating procedure. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Stanford University and written informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants or their legally authorized representative.

Blood collection and processing were done according to a rigorous standardized protocol to minimize variation associated with blood draw and blood processing. Briefly, about 10 cc of whole blood was collected in 4 vacutainer EDTA tubes (Becton Dickinson vacutainer EDTA tube) and spun at 1,800g for 10 min to separate out plasma, leaving 1 cm of plasma above the buffy coat and taking care not to disturb the buffy coat to circumvent cell contamination. Plasma was aliquoted into polypropylene tubes and stored at −80 °C. Plasma processing times averaged approximately 1 h from the time of the blood draw to the time of freezing and storage. All draws were done in the morning to minimize the impact of circadian rhythm on protein concentrations.

CSF was collected via lumbar puncture after an overnight fast, using a 20–22G spinal needle that was inserted in the L4–L5 or L5–S1 interspace. CSF samples were immediately centrifuged at 500g for 10 min, aliquoted in polypropylene tubes and stored at −80 °C.

Plasma samples from all Stanford cohorts were sent for proteomics using the SomaScan platform (SomaScan 7K) in the same batch. CSF samples from all Stanford cohorts were sent for proteomics using the SomaScan platform (SomaScan 5K) in the same batch. A total of 304 participants from Stanford with paired CSF and plasma samples taken with a range of <120 d between draws were included in the present study. Per-cohort sample sizes are as follows: ADRC. n = 119; SAMS, n = 128; BPD, n = 49; and SCMD, n = 8.

Stanford-ADRC

Samples were acquired through the National Institute on Aging (NIA)-funded Stanford-ADRC. Samples used in the present study were collected between 2015 and 2020. The Stanford-ADRC cohort is a longitudinal observational study of participants with clinical dementia and age- and sex-matched, nondemented participants. All HC participants were deemed cognitively unimpaired during a clinical consensus conference which included board-certified neurologists and neuropsychologists. Cognitively impaired participants underwent CDR and standardized neurological and neuropsychological assessments to determine cognitive and diagnostic status, including procedures of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (https://naccdata.org). Cognitive status was determined in a clinical consensus conference that included neurologists and neuropsychologists. All participants were free from acute infectious diseases and in good physical condition.

SAMS

Stanford Aging and Memory Study (SAMS) is an ongoing longitudinal study of healthy aging. Samples used in the present study were collected between 2014 and 2019. Blood and CSF collection and processing were carried out by the same team and using the same protocol as in Stanford-ADRC. Neurological and neuropsychological assessments were performed by the same team and used the same protocol as in Stanford-ADRC. All SAMS participants had CDR = 0 and a neuropsychological test score within the normal range; all were also deemed cognitively unimpaired during a clinical consensus conference that included neurologists and neuropsychologists.

Stanford-BPD study

The Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease (BPD) cohort64 was a Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research-funded longitudinal study of biological markers associated with cognitive decline in people with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Research participants were recruited from the Stanford Movement Disorders Center between 2011 and 2015 with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease according to UK Brain Bank criteria and required bradykinesia with muscle rigidity and/or rest tremor. All participants completed baseline cognitive, motor, neuropsychological, imaging and biomarkers assessments (plasma and optional CSF) including Movement Disorders Society, revised Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS). Age-matched HCs were also recruited to control for age-associated biomarker changes. After the comprehensive neuropsychological battery all participants were given a cognitive diagnosis of no cognitive impairment, mild cognitive impairment or dementia, according to published criteria.

SCMD

The Stanford Center for Memory Disorders (SCMD) cohort study was an NIA-funded cross-sectional study of people across the cognitive continuum. Participants with mild dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) were recruited from the SCMD between 2011 and 2015. Participants were included if they had a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease dementia (amnestic presentation) according to the NIA–Alzheimer’s Association65 (NIA-AA) criteria and a CDR score of 0.5 or 1, or a diagnosis of MCI according to the NIA-AA criteria65, a score of 1.5 s.d. values below age-adjusted normative means on at least one test of episodic memory and a CDR score of <1. Older HCs were recruited from the community, selected to have a similar average age to enrolled patients and required to have normal neuropsychological performance and a CDR score of 0. Participants completed cognitive, neuropsychological, imaging and biomarker assessments in CSF and plasma.

Knight-ADRC

The Knight-ADRC cohort is an NIA-funded longitudinal observational study of participants with clinical dementia and age-matched controls. Research participants at the Knight-ADRC undergo longitudinal cognitive, neuropsychological, imaging and biomarker assessments including CDR score. Among individuals with CSF and plasma data, cases with Alzheimer’s disease corresponded to those with a diagnosis of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) using criteria equivalent to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke—Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association for probable Alzheimer’s disease. Controls received the same assessment as the cases but were nondemented (CDR = 0). Written informed consent was obtained from participants or their family members. Samples used in the present study were collected between 2006 and 2018. The IRB of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis approved the study and research was performed in accordance with the approved protocols.

Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes (Becton Dickinson vacutainer, purple top) at the visit time, immediately centrifuged at 1,500g for 10 min, aliquoted on two-dimensional, barcoded Micronic tubes (200 μl per aliquot) and stored at −80 °C. The plasma was stored in a monitored −80 °C freezer until it was pulled and sent to SomaLogic (SomaScan 7K) for data generation.

CSF samples were collected through lumbar puncture from participants after an overnight fast. Samples were processed and stored at −80 °C until they were sent for protein measurement (SomaScan 7K). A total of 243 participants from Knight-ADRC with paired CSF and plasma samples taken with a range of <120 d between draws were included in the present study.

GNPC

The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC) is a major neurodegenerative disease biomarker discovery effort, which hosts the largest collection of SomaScan data (>40,000 patient samples from >20 international research groups) from patient samples across healthy aging, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and FTD. All cohorts and data were anonymized. Ethics approval for each individual cohort was obtained from their respective IRBs. All participating cohorts confirmed that informed consent was obtained from all individuals contributing clinical and generated biosample data prior to contributing data to the GNPC. Some 1,624 individuals from the GNPC had paired CSF and plasma SomaScan data available from the same visit which were utilized in the present study, comprising 1,358 individuals from contributor Q and 266 individuals from contributor N. All plasma samples utilized in the present study were collected in EDTA tubes. Although both Stanford and Knight-ADRC contributed some samples to the GNPC, not all samples utilized in the present study are included in the V1 release of the GNPC, and contributors N and Q are distinct, independent study sites.

Proteomics

The SomaLogic (https://somalogic.com) SomaScan assay66,67, which uses slow off-rate modified DNA aptamers (SOMAmers) to bind target proteins with high specificity, was used to quantify the relative concentration of thousands of human proteins in plasma and CSF in the Stanford, Knight-ADRC and GNPC cohorts. The v.4.1 (~7,000 proteins) assay was used for all of the cohorts and samples, except for Stanford CSF, for which the v.4.0 (~5,000 proteins) assay was used. All v.4 targets were included in the v.4.1 assay based on SeqId and only the v.4 targets were analyzed for the present study. In addition, proteins were filtered based on their detection in the CSF and plasma. The estimated limit of detection (eLOD) was calculated for each protein using the formula eLOD = Mbuffers + 4.9 × MADbuffers, where Mbuffers is the buffer median measurement and MADbuffers is the median absolute deviation of buffer measurements for the relevant run. Only the 2,304 proteins that had values above eLOD in the CSF and plasma of >60% of participants were retained for analysis.

Standard SomaLogic normalization, calibration and quality control were performed on all samples, resulting in protein measurements in relative fluorescence units (r.f.u.). In brief, pooled reference standards and buffer standards are included on each plate to control for batch effects during assay quantification. Samples are normalized within and across plates using median signal intensities in reference standards to control for both within-plate and across-plate technical variation. Samples were further normalized to a pooled reference using an adaptive maximum likelihood procedure. Samples were additionally flagged by SomaLogic if signal intensities deviated significantly from the expected range and these samples were excluded from analysis. The resulting values are the provided data from SomaLogic and are considered ‘raw’ data.

CSF to plasma proteomic ratios were calculated by dividing the raw CSF r.f.u. value by the raw plasma r.f.u. value for each protein and each individual. As r.f.u. values are relative units rather than absolute quantifications of protein level, the CSF to plasma ratios from the present study cannot be used to quantify differences in absolute protein concentrations in the CSF versus plasma. All analyses in the present study describe changes in these relative CSF to plasma ratios of the same protein, between individuals.

Identification of peripherally and CNS-enriched proteins

We used the GTEx human tissue bulk RNA-seq database68 to classify proteins as primarily produced in either peripheral organs or the CNS or expressed in both places. We used RNA-seq data rather than proteomic data to perform this classification because secreted proteins can travel throughout the body before quantification, whereas RNA expression levels more closely indicate a protein’s original source of production. Tissue gene expression data were normalized using the DESeq2 (ref. 69) R package. In accordance with previous work12,70, a gene was considered enriched in the brain if it was expressed at least 4× higher in the brain compared with any other tissue, and a gene was considered enriched in the periphery if the peripheral tissue with maximum gene expression had levels at least 4× higher than brain expression levels. Maximal expression levels across all brain regions for each gene were taken to represent that gene’s brain expression. Genes that were not enriched in either the brain or the periphery were categorized as expressed in both places. Enriched genes were mapped to the proteins quantified by the SomaScan assay. For aptamers targeting multiple proteins, all targets were required to be enriched in the relevant compartment. In addition, as expression of genes that are typically considered peripherally specific may increase in the brain with age, we changed the annotation of 56 proteins with expression that increased with age in any of 14 brain regions analyzed by Peng et al.71 from ‘peripheral’ to ‘both’. In total, 742 proteins were primarily peripherally derived, 119 proteins were primarily brain derived and 1,443 proteins were expressed in both compartments.

Biophysical characteristics of proteins

Biophysical protein data, including amino acid sequence, mass and annotated structural domains, were downloaded from UniProtKB and matched to SomaLogic proteins using UniProt IDs. Only the 727 aptamers targeting a single peripherally derived protein were included in these analyses. Protein charge at pH 7.4, the pH of blood, was calculated from each protein’s amino acid sequence using the charge_at_pH method from the Biopython package Bio.SeqUtils.IsoelectricPoint, which calculates the net charge of a protein at a given pH by summing the contributions of ionizable amino acids, using the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation to estimate the fractional charge of each residue based on its pKa and the pH. Enrichment for specific protein domains within a set of proteins of interest was calculated using two-sided Fisher’s exact tests, with all other proteins measured by the SomaLogic 5K assay used as the background set. Multiple hypothesis testing correction was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg method and the significance threshold was set at a 5% false discovery rate (FDR; q < 0.05).

Genomics

Genomic datasets from Knight-ADRC72 were genotyped on multiple arrays at different times and were imputed individually using the GRCh38 v.R2 reference panel on the TOPMed Imputation Server. Before imputation, high-quality directly sequenced variants were filtered based on the following criteria: (1) genotyping rate ≥98% per SNP or individual; (2) minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.01; and (3) Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P ≥ 1 × 10−6. Data were filtered to the 243 participants with CSF and plasma proteomic data available. After imputation and merging the data from the different arrays, only SNPs with an overall genotyping rate ≥95% were included. Genomic samples from Stanford were whole-genome sequenced, aligned to GRCh38, haplotype phased and joint called using the GATK4 pipeline and variants were filtered based on genotyping rate ≥95% and HWE P ≥ 1 × 10−8. Only SNPs present in both datasets were included in the analysis.

Statistical analyses

Association of ratios with individual traits

Linear regression to assess the relationships between ratios and age, sex or cognitive testing scores was performed using the OLS function from the statsmodels73 Python package, using the HC3 covariance matrix for robustness to heteroscedasticity. Age and sex were used as covariates in all regression analyses. Meta-analyses of the effects in the Knight-ADRC and Stanford cohorts were performed using inverse-variance-weighted fixed-effect models with the metafor package in R. Ratio associations with age and sex in Stanford and Knight-ADRC cohorts were performed only in clinically normal participants, additionally excluding those with a CDR-global score >0. Ratio associations with age and sex in GNPC were performed only in clinically normal participants, in addition to excluding those with an MMSE score <24 or a MoCA score <26, and contributor code was used as an additional covariate. Multiple hypothesis testing correction was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg method and the significance threshold was set at a 5% FDR (q < 0.05).

For the meta-analyses of associations of DCUN1D1, MFGE8 and VEGFA ratios with cognitive impairment across cohorts, cognitive test scores were z-score normalized before linear regression with age and sex as covariates and meta-analyses were performed to aggregate effects across cohorts. Random-effects models were used to account for potential heterogeneity based on the different tests used to assess cognitive impairment. Effect sizes indicate the estimated percentage change in average ratio level per s.d. change in cognitive impairment (that is, an effect size of −0.1 indicates a 10% decrease in average ratio level per s.d. increase in cognitive impairment).

Pathway enrichment

Enrichment analyses for GO Cellular Component, Biological Process and Molecular Function gene sets were performed using g:Profiler74, with the set of proteins measured by SomaLogic used as the background distribution.

Ratio QTL identification

We performed CSF to plasma protein ratio QTL analysis separately in the Knight-ADRC (n = 243) and Stanford (n = 208) cohorts using Plink v.2 (ref. 75). Before QTL analysis, ratio outliers, defined as values that were >3× the IQR below the first quartile or above the third quartile for each protein, were removed, to avoid their excessive influence on associations with rare variants. Genotype data were filtered to include only autosomal variants with MAF ≥ 0.01. Association testing was conducted using the --glm function with the firth-fallback option. The model included covariates for sex, age and the top ten genotype principal components (PCs) to account for population structure. Cohort-specific summary statistics were harmonized, and meta-analysis was performed using inverse-variance-weighted fixed-effect models with Plink v.1.9. SNP ratio associations were considered significant if the meta-analysis P < 2.17 × 10−11, which corresponds to the conventional genome-wide significance threshold of 5 × 10−8, adjusted for multiple testing using Bonferroni’s correction to account for the 2,304 protein ratios tested.

Individual loci associated with protein ratios were defined using a distance-based method. For each aptamer, we scanned the genome to identify the most significant variant–aptamer association that passed the study-wide multiple-testing correction criteria and defined it as the index variant for that association. We then grouped and removed all associations within 1 Mb of the index variant, considering them to be part of the same locus. We performed the same procedure for the next most significant variant–aptamer association (if applicable) until no associations reached the study-wide significance threshold.

Variant annotation

Transcript start and end sites from human genome assembly GRCh38 were downloaded from Plink. A ratio QTL was defined as cis if it was located within 1-Mb distance76 from the transcript start or end site of any protein targeted by the somamer. Variants further than 1 Mb from any gene targeted by the somamer were designated as trans. For all variants significantly associated with a CSF to plasma ratio, the predicted impacted gene and variant function were annotated using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor v.113 (ref. 77).

Colocalization of ratio QTLs with CSF and plasma pQTLs

We used single-variant Bayesian colocalization78 (coloc R package, v.5.2.3) to determine whether each ratio QTL shared an association with pQTLs for protein levels in CSF41 and plasma40, using the largest pQTL resources generated using the SomaScan platform for each fluid. The proteomic data from the CSF pQTL resource were generated using the SomaScan 7K platform and the proteomic data from the plasma pQTL resource were generated using the SomaScan 5K platform. Somamer IDs were used to match proteins across studies. For each ratio QTL, we selected all variants within 1 Mb of the index ratio QTL position. The s.e. for the ratio QTL summary statistics was calculated using s.e. = ABS(effect size/qnorm(P/2)) and all variants with effect sizes of 0 were removed. We filtered to select only variants that were present in both analyzed datasets (either ratio and CSF or ratio and plasma). We further harmonized the effect alleles between studies so that effect estimates reflected the same reference allele across datasets. Variance was calculated for each variant in each study by taking the square of the s.e. values. For each study, effect sizes, variances, IDs, positions and MAFs (calculated from either the CSF or plasma datasets) for each variant were supplied to the coloc.abf() function to test for a shared causal variant between the ratio QTL and each of the fluid-specific QTLs. We used the default prior probabilities of P1 = 1 × 10−4, P2 = 1 × 10−4 and P12 = 1 × 10−5. Determination of shared causal variants was made based on PP.H4 > 0.8.

Quantification of FCN2 isoforms

Expression levels of FCN2’s alternative transcripts (ENST00000350339.3 and ENST00000291744.10) were tested for association with participant genotype at chr9:134883293:A>G. Genotype data from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and transcript-level RNA-seq expression quantified by RSEM (RNA-seq by expectation-maximization) from the GTEx v.8 dataset68 were used. Linear regression was used to determine whether the genotype at chr9:134883293 was significantly associated with a change in expression level for either transcript. For each transcript separately, inverse normal-transformed expression levels were regressed against genotype, adjusting for covariates included in the GTEx v.8 release, including three genotype PCs, genotyping platform, sex and PEER factors. Nominal P values were estimated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. As for all box plots in the manuscript, the center line represents the median, the box limits the upper and lower quartiles, the whiskers the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× the IQR from the box limits and the points outliers.

Structural modeling of FCN2

The three-dimensional structure of human FCN2 protein was predicted using AlphaFold 3 (ref. 79), which implements deep learning techniques to generate highly accurate protein structure predictions. The full-length protein sequence and a trimmed isoform variant were submitted to the AlphaFold 3 server. The resulting protein models were visualized and analyzed using UCSF ChimeraX v.1.10 (ref. 80), with structures colored according to the predicted local distance difference test confidence scores. Structural alignments between the full-length FCN2 and the isoform variant were performed using the ‘match’ command in ChimeraX to assess conformational differences. The aligned structures were rendered side by side for comparative analysis, with special attention given to regions showing notable conformational divergence.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The harmonized GNPC data used to generate these findings were provided to Consortium Members in June 2024 and will be made available for public request by the AD Data Initiative by 15 July 2025. Members of the global research community will be able to access the metadata and place a data use request via the AD Discovery Portal (https://discover.alzheimersdata.org). Access is contingent on adherence to the GNPC Data Use Agreement and the Publication Policies. Full Stanford and Knight-ADRC data are available with formal applications submitted to the respective cohort committees to protect patient-sensitive data. Requesters can expect to receive data within 2–4 months. Stanford data (including the Stanford-ADRC, SAMS, BPD and SCMD) can be requested at https://web.stanford.edu/group/adrc/cgi-bin/web-proj/datareq.php. Data from specific Stanford cohorts can be requested from the following cohort leaders: ADRC: T.W.-C. (twc@stanford.edu); SAMS: E.M. (bmormino@stanford.edu) or A.D.W. (awagner@stanford.edu); and BPD and SCMD: K.L.P. (klposton@stanford.edu). The Knight-ADRC proteomics data were generated by the laboratory of the principal investigator C.C. (cruchagac@wustl.edu) and can be requested at https://knightadrc.wustl.edu/professionals-clinicians/request-center-resources/submit-a-request.

References

Hou, Y. et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15, 565–581 (2019).

Harada, C. N., Natelson Love, M. C. & Triebel, K. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 29, 737–752 (2013).

Montagne, A. et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 85, 296–302 (2015).

Banks, W. A., Reed, M. J., Logsdon, A. F., Rhea, E. M. & Erickson, M. A. Healthy aging and the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Aging 1, 243–254 (2021).

Nehra, G., Bauer, B. & Hartz, A. M. S. Blood-brain barrier leakage in Alzheimer’s disease: from discovery to clinical relevance. Pharmacol. Ther. 234, 108119 (2022).

Ryu, J. K. & McLarnon, J. G. A leaky blood–brain barrier, fibrinogen infiltration and microglial reactivity in inflamed Alzheimer’s disease brain. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 2911–2925 (2009).

Al-Bachari, S., Naish, J. H., Parker, G. J. M., Emsley, H. C. A. & Parkes, L. M. Blood–brain barrier leakage Is increased in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Physiol. 11, 593026 (2020).

Gerrits, E. et al. Neurovascular dysfunction in GRN-associated frontotemporal dementia identified by single-nucleus RNA sequencing of human cerebral cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 1034–1048 (2022).

Kadry, H., Noorani, B. & Cucullo, L. A blood–brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS 17, 69 (2020).

Yang, A. C. et al. Physiological blood-brain transport is impaired with age by a shift in transcytosis. Nature 583, 425–430 (2020).

Roche, S., Gabelle, A. & Lehmann, S. Clinical proteomics of the cerebrospinal fluid: towards the discovery of new biomarkers. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2, 428–436 (2008).

Oh, H. S.-H. et al. Organ aging signatures in the plasma proteome track health and disease. Nature 624, 164–172 (2023).

Banks, W. A. From blood–brain barrier to blood–brain interface: new opportunities for CNS drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 275–292 (2016).

Ke, W. et al. Gene delivery targeted to the brain using an Angiopep-conjugated polyethyleneglycol-modified polyamidoamine dendrimer. Biomaterials 30, 6976–6985 (2009).

Demeule, M. et al. Identification and design of peptides as a new drug delivery system for the brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324, 1064–1072 (2008).

Seeliger, T. et al. Comparative analysis of albumin quotient and total CSF protein in immune-mediated neuropathies: a multicenter study on diagnostic implications. Front. Neurol. 14, 1330484 (2024).

Musaeus, C. S. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid/plasma albumin ratio as a biomarker for blood-brain barrier impairment across neurodegenerative dementias. J. Alzheimers Dis. 75, 429–436 (2020).

LeVine, S. M. Albumin and multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 16, 47 (2016).

Huang, M. et al. Structural basis of membrane binding by Gla domains of vitamin K-dependent proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 10, 751–756 (2003).

Deane, R. et al. Endothelial protein C receptor-assisted transport of activated protein C across the mouse blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 29, 25–33 (2009).

Cicognola, C. et al. Associations of CSF PDGFRβ with aging, blood-brain barrier damage, neuroinflammation, and Alzheimer disease pathologic changes. Neurology 101, e30–e39 (2023).

Fishman, J. B., Rubin, J. B., Handrahan, J. V., Connor, J. R. & Fine, R. E. Receptor-mediated transcytosis of transferrin across the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurosci. Res. 18, 299–304 (1987).

Moon, Y., Lim, C., Kim, Y. & Moon, W.-J. Sex-related differences in regional blood–brain barrier integrity in non-demented elderly subjects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2860 (2021).

Shao, X. et al. Age-related decline in blood-brain barrier function is more pronounced in males than females in parietal and temporal regions. eLife 13, RP96155 (2024).

Park, H.-K. & Ahima, R. S. Physiology of leptin: energy homeostasis, neuroendocrine function and metabolism. Metabolism 64, 24–34 (2015).

Qi, Y. et al. Adiponectin acts in the brain to decrease body weight. Nat. Med. 10, 524–529 (2004).

Morton, G. J. & Schwartz, M. W. Leptin and the central nervous system control of glucose metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 91, 389–411 (2011).

Oh, H. S.-H. et al. A cerebrospinal fluid synaptic protein biomarker for prediction of cognitive resilience versus decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 31, 1592–1603 (2025).

Ali, M. et al. Multi-cohort cerebrospinal fluid proteomics identifies robust molecular signatures across the Alzheimer disease continuum. Neuron https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2025.02.014 (2025).

Petersen, M. A., Ryu, J. K. & Akassoglou, K. Fibrinogen in neurological diseases: mechanisms, imaging and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 283–301 (2018).

Kim, A. Y. et al. SCCRO (DCUN1D1) Is an essential component of the E3 complex for neddylation*. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33211–33220 (2008).

Marazuela, P. et al. MFG-E8 (LACTADHERIN): a novel marker associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 9, 154 (2021).

Wagner, J. et al. Medin co-aggregates with vascular amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 612, 123–131 (2022).

Guo, L.-H., Alexopoulos, P. & Perneczky, R. Heart-type fatty acid binding protein and vascular endothelial growth factor: cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 263, 553–560 (2013).

Mahoney, E. R. et al. Brain expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene family in cognitive aging and alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 888–896 (2021).

Chiappelli, M. et al. VEGF gene and phenotype relation with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Rejuv. Res. 9, 485–493 (2006).

Tarkowski, E. et al. Increased intrathecal levels of the angiogenic factors VEGF and TGF-β in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Neurobiol. Aging 23, 237–243 (2002).

Hohman, T. J., Bell, S. P., Jefferson, A. L. & for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in neurodegeneration and cognitive decline: exploring interactions with biomarkers of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 72, 520–529 (2015).

Silvestre, J.-S. et al. Lactadherin promotes VEGF-dependent neovascularization. Nat. Med. 11, 499–506 (2005).

Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1712–1721 (2021).

Western, D. et al. Proteogenomic analysis of human cerebrospinal fluid identifies neurologically relevant regulation and implicates causal proteins for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 56, 2672–2684 (2024).

Piñero, J. et al. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D845–D855 (2020).

Pluvinage, J. V. et al. Transcobalamin receptor antibodies in autoimmune vitamin B12 central deficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadl3758 (2024).

Surendran, S. et al. An update on vitamin B12-related gene polymorphisms and B12 status. Genes Nutr. 13, 2 (2018).

Zetterberg, H. et al. The transcobalamin (TC) codon 259 genetic polymorphism influences holo-TC concentration in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Alzheimer disease. Clin. Chem. 49, 1195–1198 (2003).

Kilpatrick, D. C. & Chalmers, J. D. Human l-ficolin (ficolin-2) and its clinical significance. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 138797 (2012).

Shi, L. et al. Plasma proteomic biomarkers relating to Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis based on our own studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 712545 (2021).

Osthoff, M., Walder, B., Delhumeau, C., Trendelenburg, M. & Turck, N. Association of lectin pathway protein levels and genetic variants early after injury with outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective cohort study. J. Neurotrauma 34, 2560–2566 (2017).

De Blasio, D. et al. Human brain trauma severity is associated with lectin complement pathway activation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 39, 794–807 (2019).