Abstract

The accurate and timely diagnosis of acute aortic syndrome (AAS) in patients presenting with acute chest pain remains a clinical challenge. Aortic computed tomography (CT) angiography is the imaging protocol of choice in patients with suspected AAS. However, due to economic and workflow constraints in China, the majority of suspected patients initially undergo noncontrast CT as the initial imaging testing, and CT angiography is reserved for those at higher risk. Although noncontrast CT can reveal specific signs indicative of AAS, its diagnostic efficacy when used alone has not been well characterized. Here we present an artificial intelligence-based warning system, iAorta, using noncontrast CT for AAS identification in China, which demonstrates remarkably high accuracy and provides clinicians with interpretable warnings. iAorta was evaluated through a comprehensive step-wise study. In the multicenter retrospective study (n = 20,750), iAorta achieved a mean area under the receiver operating curve of 0.958 (95% confidence interval 0.950–0.967). In the large-scale real-world study (n = 137,525), iAorta demonstrated consistently high performance across various noncontrast CT protocols, achieving a sensitivity of 0.913–0.942 and a specificity of 0.991–0.993. In the prospective comparative study (n = 13,846), iAorta demonstrated the capability to significantly shorten the time to correct diagnostic pathway for patients with initial false suspicion from an average of 219.7 (115–325) min to 61.6 (43–89) min. Furthermore, for the prospective pilot deployment that we conducted, iAorta correctly identified 21 out of 22 patients with AAS among 15,584 consecutive patients presenting with acute chest pain and under noncontrast CT protocol in the emergency department. For these 21 AAS-positive patients, the average time to diagnosis was 102.1 (75–133) min. Finally, iAorta may help prevent delayed or missed diagnoses of AAS in settings where noncontrast CT remains the only feasible initial imaging modality—such as in resource-limited regions or in patients who cannot receive, or did not receive, intravenous contrast.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite recent advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, acute aortic syndrome (AAS) remains a catastrophic cardiovascular emergency associated with high mortality rates1,2. Approximately 40–50% of patients with AAS die within 48 h of its onset, and mortality increases by 1–2% per hour without appropriate management3,4. Delays in diagnosis and treatment substantially worsen prognosis, underscoring the need for rapid and accurate identification of AAS2,5. Clinical symptoms of AAS are often nonspecific and variable, ranging from acute aortic chest pain that can mimic other acute conditions to atypical or mild presentations6,7,8. In addition, physical examinations and routine laboratory tests lack sensitivity and specificity for confirming or ruling out AAS, complicating timely diagnosis9,10,11.

Aortic computed tomography (CT) angiography (CTA) is the imaging protocol of choice in patients with suspected AAS, yielding high sensitivity and specificity1,2. However, CTA is costly and carries risks of contrast-induced complications, such as anaphylaxis and nephrotoxicity11,12,13. Furthermore, the true incidence of AAS among patients undergoing CTA for suspected AAS has been found to be only 2.7% (refs. 14,15). In China, the cost of CTA is approximately five times higher than that of noncontrast CT, and healthcare resources remain notably limited compared with developed countries16,17. Considering both cost and resource constraints, Chinese clinical guidelines and current practice recognize that noncontrast chest and abdominal CT imaging can provide a rapid and straightforward initial assessment for considered as less critical conditions, while CTA is reserved for patient cases with highly suspicious findings or a high clinical risk of AAS18. Similarly, in low- and middle-income countries, limited access to iodinated contrast media and financial constraints further restrict the use of CTA19,20. In this context, patients in China or low- and middle-income countries may frequently undergo noncontrast CT for AAS evaluation and triage, despite its limited sensitivity, which creates notable diagnostic challenges even for experienced radiologists and clinicians.

The potential of using noncontrast CT for screening AAS has been explored previously21,22, and it is often performed as a standard practice along with contrast CT for the purpose of better visualized for intramural hematoma (IMH)23,24. The diagnostic performance of noncontrast CT alone, however, has not been well characterized in prior studies. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL) algorithms, have demonstrated superior capabilities in extracting and identifying latent and clinically relevant features from medical images. In the settings of cost-prohibitive or limited availability contrast CT, an AI tool with high sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) can help to improve the diagnostic confidence for extracting patients with AAS from noncontrast CT examinations and direct the use of CTA to these patients with higher likelihood of AAS based on AI evaluation via noncontrast CT. Furthermore, it can help prevent delayed or missed diagnosis of AAS in settings where noncontrast CT remains the only feasible initial imaging modality.

In this study, we developed and validated an AI-based system, iAorta, to identify AAS rapidly and accurately on noncontrast CT scans in real-world emergency settings in China. Designed to automatically analyze noncontrast CT scans from patients presenting with acute chest pain, iAorta provides early warnings of AAS to radiologists, when necessary, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. To train the DL model, we collected aortic CTA scans with paired arterial and noncontrast CT phase series. In stage I, the diagnostic performance and generalizability of the model were evaluated across eight hospitals in China. In stage II, we assessed AI-assisted performance improvements in diagnostic accuracy by providing radiologists with interpretable model predictions. In stage III, we evaluated the model’s robustness across various noncontrast CT protocols. In stage IV, we developed the iAorta system to achieve practical clinical applications in two prospective trials. A prospective multicenter study, including a comparative analysis and a pilot deployment, was conducted to assess the feasibility of integrating iAorta into real-world emergency department (ED) workflows.

a, Clinical starting point for the study. The diagnosis of AAS poses a notable challenge within the ED owing to its nonspecific clinical symptoms. In China, more than half of the patients with acute chest pain are initially suspected of less critical illnesses and thus received noncontrast CT scans as the initial imaging test. Our goal is to develop an AI model that can rapidly and accurately identify patients with suspected AAS from this population of individuals undergoing noncontrast CT scans, while providing interpretable results to assist radiologists and physicians in making informed clinical decisions. b, A schematic overview of the model. It was trained with patient-level diagnostic labels and segmentation masks annotated on arterial phase series. The model takes noncontrast phase series as input and outputs the probability of AAS, segmentation masks of the aortic wall and true lumen, and an activation map highlighting potential lesion areas. c, Retrospective and prospective evaluation of model and iAorta. Retrospective evaluation for model consists of multicenter model validation (stage I, n = 20,750), reader study (stage II, n = 2,287) and large-scale real-world study (stage III, n = 137,525). Prospective evaluation (stage IV) for iAorta consists of comparative study (n = 13,846) and pilot deployment study (n = 15,584). iAorta incorporates a phase selection module, our model and a pop-up warning module.

The study findings highlight the notable potential of our iAorta system as a vital decision-support tool in emergency care settings where contrast CT is either cost-prohibitive or unavailable to provide directly. On delivering accurate, rapid and interpretable visual warnings, iAorta can facilitate and enable timely and informed clinical decisions. In sites with multiphase CT protocols for AAS evaluation, iAorta’s high specificity and high NPV on noncontrast CT scans may help to avoid unnecessary contrast injections in low-risk patients, particularly younger individuals. This not only reduces the risks associated with contrast agents, such as nephrotoxicity and allergic reactions, but also decreases cumulative radiation exposures from additional postcontrast imaging, thereby enhancing patient safety.

Results

Overview of the study

We conducted this stepwise study in four stages with nine hospitals across China to develop and validate the iAorta system for the effective detection of AAS, that is, Stanford type A aortic dissection (TAAD), Stanford type B aortic dissection (TBAD), IMH and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer (PAU), in real-world emergency settings. In stage I, we evaluated the model in an internal validation cohort (n = 2,287) and seven external validation cohorts (n = 18,463). In stage II, we compared the model performance with radiologists of varying expertise levels and radiologists assisted by AI on noncontrast CT. In stage III, we retrospectively tested the model in real-world emergency scenarios of three representative medical centers, involving a total of 145,201 various noncontrast CT scans from 137,525 consecutive patients presented with acute chest pain symptoms. In stage IV, we developed a real-time ‘hyperlink message’ warning system, iAorta, and integrated it into the existing clinical workflow. To assess its impact on improving the identification of AAS on noncontrast CT and reducing the time to the correct diagnostic pathway, we further conducted a prospective, multicenter study. This study included a comparative study of 14,436 noncontrast CT scans from 13,846 consecutive patients and, more importantly, a pilot deployment study on 16,054 noncontrast CT scans from 15,584 consecutive patients (running from 20 December 2024 to 28 February 2025). The baseline demographic information and image characteristics of all cohorts are summarized in Extended Data Table 1. Patient and data sources of model development, multicenter model validation, reader study, retrospective large-scale real-world study and prospective multicenter study are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1.

Development of the iAorta system

Model development

To obtain accurate diagnosis labels and lesion regions, we collected 3,350 aortic CTA scans, including arterial and noncontrast phase series, to train the model. The arterial phase series were used as the gold standard for diagnosing AAS and suggesting lesion areas, while the noncontrast phase series were used for model training under the supervision of the diagnostic labels and the segmentation labels that are transferred by image registration technique from lesion annotations on paired arterial phase series. Our model can detect the presence or absence of AAS at the patient level, segmenting the aorta and true lumen precisely, and localizing and identifying potential lesion regions reliably to enhance slice-level interpretability. The final outputs generated by our model are fed back into the iAorta system to send timely alerts to radiologists, facilitating the rapid referral of high-risk patients for further aortic CTA examination and confirmation, ensuring prompt diagnosis and effective intervention. More details about the annotations and model architecture are provided in the Methods and are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2. Quantitative analysis is provided in Supplementary Section 2.6 (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Model visualization and explanation

We generated activation maps by mapping the normalized activation scores to their corresponding spatial location in each CT slice, as shown in Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 3. Technical details on the generation of activation maps are provided in the Methods. In our task, the regions with high activation scores typically corresponded to relevant abnormal areas, whereas low activation scores indicated healthy aortic areas. There is a visible difference in the appearance of activation maps between different subtypes. The high activation regions of AD and IMH are more refined and larger, whereas those of PAU are coarser and smaller. This observation is consistent with their representations of subtypes. The regions with high activation scores in each slice provide valuable visual information for AI-assisted detection of AAS in the ED. Further quantitative analysis revealed that the diagnostically relevant regions generated by the model improved the sensitivity of radiologists’ assessments on AAS when using our iAorta system. We have developed a browser–server collaborative early warning system designed for rapid and accurate detection of AAS in real-world clinical medical settings. Integrated with a noncontrast CT phase selection tool, our developed model and a warning pop-up plugin, the system can process and analyze large amounts of patient data in real time, enabling radiologists to get timely alerts and make informed diagnosis and intervention. The browser-based interface ensures that the system is accessible from any device with an internet connection, enhancing its usability and flexibility. This system is designed to be highly secure, with strict data privacy and security protocols in place to protect sensitive patient information. The iAorta system both enhances the efficiency and accuracy of AAS detection and provides a scalable and secure solution for clinical use. Further details about the collaborative system are provided in the Methods.

Stage I—multicenter model validation

To assess the generalizability and robustness of our model to various patient populations, we collected 20,750 aortic CTA scans, including arterial and noncontrast phase series similar to those used in model training, from eight hospitals across China. The diagnosis labels were confirmed using the corresponding paired arterial phase series. In this internal validation cohort, the overall model performance in detecting AAS on noncontrast CT achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.980 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.973–0.987) (Fig. 2a), a sensitivity of 0.984 (95% CI 0.972–0.990) and a specificity of 0.947 (95% CI 0.935–0.957). In the external validation cohorts, the performance of AAS detection obtained an AUC of 0.941–0.972, a sensitivity of 0.954–0.975 and a specificity of 0.929–0.946 (Fig. 2b,c). Furthermore, we conducted a subgroup analysis performance for different subtypes of AAS. We divided AAS into four subtypes, TAAD, TBAD, IMH and PAU, based on the severity of the condition. Details about the diagnostic criteria are provided in the Methods. The model achieved a sensitivity of 0.971–0.995 for TAAD, 0.980–0.996 for TBAD, 0.953–0.980 for IMH and 0.912–0.955 for PAU (Fig. 2d), respectively. Detailed evaluation metrics, including accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), NPV and F1 score, are presented in Extended Data Table 2.

a, ROC curves of AAS detection on the internal and external validation cohorts. b, Sensitivity of AAS detection in the internal validation cohort (n = 795) and external validation cohorts (cohorts 1–7, n = 6,495). The error bars denote the two-sided 95% CI computed from 1,000 bootstrapping iterations. c, Confusion matrices of AAS detection on the internal and external validation cohorts showing TPs, TNs, FPs, and FNs, with sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV calculated accordingly. d, Sensitivity of four subtypes (TAAD, TBAD, IMH and PAU) of AAS detection in the internal cohorts (n = 795) and external validation cohorts (cohorts 1–7, n = 6,495). The error bars denote the two-sided 95% CI computed from 1,000 bootstrapping iterations. FPs, false positives; FNs, false negatives; TPs, true positives; TNs, true negatives.

Stage II—reader study

To further assess the model performance and explore the value of clinically interpretable results in assisting for the detection of AAS, we conducted a two-stage reader study using the internal validation cohort. We recruited 11 radiologists with varying degrees of expertise (specialty experts in cardiovascular, board-certified general radiologists and medical trainees) to participate in the study. In the first stage of this study, radiologists were asked to independently diagnose each case as either AAS or non-AAS within a specified time limit, without any knowledge of the results produced by the AI model. After a 2-month washout period and randomization of the data, the same group of radiologists were given the interpretable results (in the form of distance maps) and diagnostic probabilities output from our AAS model to assist in their reassessment of patients’ diagnoses again, without prior knowledge of the model’s diagnostic accuracy. The detailed results are shown in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Table 3.

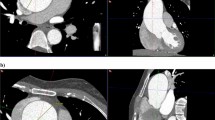

a, Comparison between the DL model and 11 radiologists with different levels of expertise on noncontrast CT for AAS detection, with or without the assistance of model. b, Sensitivity of 11 radiologists with different levels of expertise on noncontrast CT for four different subtypes of AAS detection, with or without the assistance of model (n = 795 data samples). On each box in b, the central line indicates the median, and the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. c, Examples of the ‘visible’ positive case of TBAD, ‘invisible’ positive case of IMH and negative case with an ascending aorta artifact, which was not detected by readers on noncontrast CT but well classified with the assistance of the model.

Overall, the performance of all 11 radiologists—whether diagnosing independently or with AI assistance—was lower than the performance indicated by the model’s ROC curves alone. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, in independent diagnoses, the sensitivity levels varied greatly among the 11 radiologists, with 0.807 (95% CI 0.795–0.819) for specialty experts, 0.778 (95% CI 0.764–0.796) for board-certified radiologists and 0.603 (95% CI 0.588–0.619) for medical trainees, which were significantly lower than those of the model (0.984, 95% CI 0.972–0.990, P < 0.001). When radiologists were assisted by the model, the sensitivities of specialty experts, board-certified radiologists and medical trainees all increased significantly, reaching 0.943 (95% CI 0.930–0.958, P < 0.001), 0.899 (95% CI 0.887–0.913, P < 0.001) and 0.919 (95% CI 0.906–0.933, P < 0.001), respectively. The improvement was especially notable among medical trainees, whose performance approached or even surpassed that of specialty experts when aided by AI. This highlights the model’s ability to effectively bridge the diagnostic performance gap across varying levels of expertise.

For detecting AAS from its specific subtypes (Fig. 3b), the mean sensitivities of radiologists were 0.700 (95% CI 0.677–0.732) in TAAD, 0.741 (95% CI 0.701–0.796) in TBAD and 0.647 (95% CI 0.599–0.693) in IMH, which were significantly greater than the score of 0.382 (95% CI 0.304–0.477) in PAU. With AI assistance, the mean sensitivity of radiologists improved significantly, reaching 0.893 (95% CI 0.865–0.927, P < 0.001) in TAAD, 0.941 (95% CI 0.896–0.982, P < 0.001) in TBAD, 0.859 (95% CI 0.814–0.900, P < 0.001) in IMH and 0.738 (95% CI 0.664–0.789, P < 0.001) in PAU. These results demonstrate that AI assistance markedly enhanced radiologist performance in more clinically urgent subtypes (for example, TAAD and TBAD) and diagnostically elusive cases such as PAU, for which sensitivity nearly doubled.

Remarkedly, our model has shown the ability to discern specific AAS images that remain elusive even with AI assistance to radiologists. As shown in Fig. 3c, for the ‘visible’ AAS case, radiologists were able to detect distinctive lesion features on noncontrast CT with AI assistance, leading to a revision of their initial diagnosis. However, for the other highly ‘invisible’ AAS case, our model provided a very high AI prediction probability and visualized lesion results, but radiologists did not consider the case to be AAS.

Stage III—large-scale, real-world, retrospective study

To further explore the model’s robustness across various noncontrast CT protocols from real-world emergencies, we performed a two-round, large-scale, real-world, retrospective study using a total of 145,201 noncontrast CT scans from 137,525 consecutive patients with acute chest pain in three hospitals. Details regarding the sources of the noncontrast CT scans are shown in Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 1. The diagnosis labels were confirmed by the conclusive diagnostic imaging or medical records within the 2-week follow-up.

a, The patients’ distribution in the study. b, The distributions of CT protocols in the study. c, The sensitivity and specificity of original model on RW1 (n = 23,094) and that of original and upgraded model on RW2 (cohorts 1–3, n = 122,107). The superscript asterisk represents results of the upgraded model. The error bars denote the two-sided 95% CI computed from 1,000 bootstrapping iterations. d, ROC curves of AAS detection on the RW1 and RW2 cohorts. Blue and orange curves represent the performance of the original model and the upgraded model, respectively. e, Model performance metrics (AUC, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity) for AAS detection across three subtypes (noncontrast chest CT (cohorts 1–3, n = 42,423), noncontrast abdominal CT (cohorts 1–3, n = 74,261) and others (cohorts 1–3, n = 5,423)) in the RW2 cohorts. The error bars denote the two-sided 95% CI computed from 1,000 bootstrapping iterations. SEN, sensitivity; SPE, specificity.

The first real-world evaluation cohort (RW1) consisted of 23,094 noncontrast CT scans of 20,832 consecutive individuals from The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (FAHZU), including 44 AAS scans. For AAS detection, the model achieved an overall sensitivity of 0.818 (95% CI 0.680–0.905) and a specificity of 0.994 (95% CI 0.993–0.995) (Fig. 4c). To comprehend the error patterns of the model across various noncontrast CT scans, a multidisciplinary team reviewed the error cases. The majority of false-negative cases occurred in cases with a limited FOV and small z-axis coverage. To improve the model performance in detecting AAS on noncontrast CT from different CT protocols, we implemented hard example mining and incremental learning techniques to upgrade the previously trained model. To evaluate the generalizability of the updated model, we conducted the second-round study (RW2) within one internal real-world cohort (n = 76,582, 69 patients with AAS) and two external real-world cohorts (n = 24,365, 26 patients with AAS; and n = 20,160, 23 patients with AAS). For AAS detection, the updated model achieved a sensitivity of 0.913–0.942, and a specificity of 0.991–0.993. Compared with the original model, the updated one retains a similar level of specificity while achieving notably increased sensitivities by 11.6–19.2% (P < 0.001). The ROC curves of both the original and upgraded models are shown in Fig. 4d. The significance test comparing the AUCs of the original and upgraded models is conducted using the Delong test. The result demonstrates that the observed differences in AUCs between the two models are significant (P < 0.001 in all three cohorts of RW2). Furthermore, Fig. 4e shows the model performance metrics (AUC, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity) for AAS detection across three subtypes (noncontrast chest CT, noncontrast abdominal CT and others) in the RW2 cohorts. These findings demonstrate that our model consistently achieves robust numerical performance results under various CT protocols.

We evaluated the potential clinical value of our proposed AI model in identifying patients with AAS. In China, initial diagnosis by emergency clinicians was based on preliminary investigation (using age, risk factors, history, pain characteristics, findings on physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG) and some laboratory tests). In this study, 127 patients with AAS (who were excluded from the cohort) were suspected of having AAS after the initial assessment, and the remaining 121 patients with AAS (31 with TAAD, 45 with TBAD, 21 with IMH and 24 with PAU) did not initially receive the proper or correct initial triage decisions from emergency clinicians and subsequently performed other CT protocols examination (mostly via noncontrast CT) as the initial imaging rule-out test. Applying our AI model helped correctly diagnose 90.1% (109/121) of patients with AAS in this subpopulation. Meanwhile, a total of 9.9% of patients (RW1: n = 6, RW2: n = 6) were missed by the AI model (Supplementary Tables 5–8); most of them (n = 11) had PAU, while the remaining patient had limited IMH. Three cases illustrating the potential benefits for patients with AAS are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4.

Stage IV—prospective multicenter study

Given the rapid progression and high mortality rate of AAS, it is imperative to minimize the risk of inaccurate initial assessment, thereby enabling and assuring timely and appropriate clinical decision-making. To address this, we developed the iAorta system, which incorporates automatically computed analysis and early warning functionalities.

Multicenter comparative study

To investigate the effectiveness of iAorta in the ED as an early AAS warning tool, we conducted a prospective study involving a cohort of 13,846 consecutive patients (14,436 noncontrast CT scans) who were initially not suspected of having AAS and underwent noncontrast CT scans (or CT protocols that included a noncontrast phase) across three medical centers. The study aimed to compare the performance of two groups of radiologists in identifying early signs of AAS: group A, independently reviewing images to mirror the current clinical workflow, and group B, performing the same task with assistance from iAorta, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. In the first group, the radiologist team, consisting of the initial reporting (IR) radiologist and the report reviewing (RR) radiologist, independently evaluate images in a sequential manner within the current clinical workflow. This process generates two independent diagnostic records: one for the IR radiologist’s diagnosis and the other for the RR radiologist’s diagnosis, for each CT scan. In the second group, patients’ CT scans are automatically fed into the iAorta system in real time, which thus produces AI-based AAS detection results. If the AI detects any abnormalities, both the IR and RR radiologists receive subsequential pop-up alerts, prompting them to prioritize the review of the AI-flagged (or AAS-positive) CT images. After reviewing the AI results, the AAS-assisted diagnosis is recorded. This process yields three independent diagnostic records for each image: the IR radiologist’s diagnosis (aided with AI), the RR radiologist’s diagnosis (aided with AI) and the AI-generated results.

a, The study involves two groups of radiologists: group A, the radiologist team, consisting of the IR radiologist and the RR radiologist, who independently evaluate images in a sequential manner, mirroring the current conventional clinical workflow; and group B, the radiologist team evaluating images assisted by the iAorta system. If iAorta detects any abnormalities, both the IR and RR radiologists receive sequential pop-up alerts, prompting them to prioritize the review of the AI-flagged AAS-positive image. RIS, radiology information system. b, The sensitivity and specificity of group A (IR radiologist and RR radiologist), group B (IR radiologist + iAorta and RR radiologist + iAorta) and iAorta system (n = 14,436 data samples). The error bars denote the two-sided 95% CI computed from 1,000 bootstrapping iterations. The P value was calculated by two-sided McNamar test (P < 0.001 (3.47 × 10−21)). c, Time from presentation to correct diagnostic pathway (group A versus group B) in the realistic clinical settings. Nine patients with AAS were identified by iAorta, yet two patients with AAS (PAU) were missed. d, An illustrative example highlights the potential benefits of using iAorta for patients with AAS who initially were suspected of having other acute conditions and underwent noncontrast CT in real-world emergency settings.iAorta has demonstrated the potential to significantly reduce the time needed to reach a correct diagnosis for this patient, from 273 min to 56 min.

In the first group, IR radiologists identified 3 out of 14 AAS-related positive results in 14,436 noncontrast CT scans, while RR radiologists detected 6 out of 14 AAS-related positive results. In the second group, after reviewing the AI-generated results, IR radiologists reported 11 out of 14 positive results, and RR radiologists found 12 out of 14 positive results. The sensitivity and specificity of IR radiologists improved from 0.214 (95% CI 0.076–0.476) to 0.786 (95% CI 0.524–0.924; P = 0.008) and from 0.983 (95% CI 0.981–0.985) to 0.991 (95% CI 0.989–0.992; P < 0.001), respectively. For RR radiologists, their sensitivity and specificity improved from 0.429 (95% CI 0.214–0.674) to 0.857 (95% CI 0.601–0.960; P = 0.031) and from 0.989 (95% CI 0.987–0.990) to 0.990 (95% CI 0.989–0.992; P = 0.165), respectively (as shown in Fig. 5b). The AI model alone demonstrated a high sensitivity score of 0.857 (95% CI 0.601–0.960), and a specificity of 0.992 (95% CI 0.990–0.993), as illustrated in Fig. 5b and Extended Data Table 4. More importantly, integrating the iAorta system into the current diagnostic workflow reduced the average time ‘from admission to correct diagnosis’ pathway for patients with AAS with initial false suspicion, significantly from an average of 219.7 (115–325) min down to 61.6 (43–89) min (as shown in Fig. 5c).

Pilot deployment

To further assess the real operational performance of iAorta, we integrated the iAorta system into the current pilot clinical routine in Shanghai Changhai Hospital, as depicted in Fig. 6a. iAorta automatically processes large volumes of CT images from the hospital Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS), identifies patients at risk of AAS and provides pop-up alerts to the diagnostic radiology team for positive cases, prompting them to prioritize review using an interactive visual interface. A detailed illustration is shown in Supplementary Video 1. With the aid of prompt and accurate warnings from iAorta, the radiologist team successfully identified 21 out of 22 patients with AAS among a cohort of consecutive 15,584 patients who underwent noncontrast CT as the initial imaging test in the ED from 20 December 2024 until 28 February 2025. One PAU patient was missed. The AAS identification performance reached an exceptional level, with a sensitivity of 0.955 (95% CI 0.864–1.000) and a specificity of 0.994 (95% CI 0.993–0.995), as shown in Fig. 6b. Note that the average diagnostic time of these 21 patients was controlled within mean 102.1 (range of 75–133) min.

a, iAorta is seamlessly incorporated into the existing pilot clinical routine. Once iAorta identifies patients at risk of AAS, it generates pop-up alerts for the radiology team, prompting them to prioritize the review of the flagged images. b, Confusion matrices of AAS detection in this study showing the TPs, TNs, FPs and FNs of AAS detection and the sensitivity (95.5%), specificity (99.4%), PPV (18.6%) and NPV (99.9%) calculated accordingly. c, Potential benefits of the iAorta system in the realistic clinical settings of China. d, An illustrative example highlighting the benefits of using iAorta for patients with AAS who initially presented with acute abdominal pain and were suspected of having other acute conditions in real-world emergency settings. While the patient initially entered an incorrect diagnostic pathway, the early warning provided by iAorta on the noncontrast CT enabled the definitive diagnosis of AAS within 94 min of hospital admission, ensuring both timely and appropriate management. FPs, false positives; FNs, false negatives; TPs, true positives; TNs, true negatives; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

In particular, in one case, a patient presented to the ED with right upper abdominal pain, as illustrated in Fig. 6d. After an initial assessment, clinical suspicion of an abdominal pathology emergency prompted the ordering of a noncontrast abdominal CT. Approximately 1 min after the CT scan was uploaded to the PACS (or 3 min after the CT scan examination), iAorta issued an early warning to the on-duty radiologist via a pop-up alert. Although the radiologist could not definitively identify or confirm signs of AAS on the noncontrast CT with the assistance of iAorta, the possibility of AAS diagnosis could not be excluded. After a multidisciplinary clinical team discussion and obtaining informed consent from the patient, an aortic CTA was performed, revealing a Stanford TBAD. Although the patient initially followed an incorrect diagnostic pathway (which is common), the early, accurate warning provided by iAorta on the noncontrast CT enabled the final definitive diagnosis of AAS within 94 min from hospital admission, ensuring both timely and appropriate patient management.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated iAorta, an AI-based real-time early warning system designed to assist radiologists and ED clinicians in accurately and rapidly detecting AAS using noncontrast CT scans alone. Through large-scale real-world retrospective and prospective validation across multiple centers in China, iAorta demonstrated robust performance, highlighting the notable potential of applying noncontrast CT as a reliable and alternative tool for AAS diagnosis. Notably, the interpretable output generated by iAorta substantially enhanced radiologists’ diagnostic confidence, indicating its critical role in supporting clinical decision-making. Importantly, our study findings highlight several key benefits of iAorta. (1) In resource-constrained settings where noncontrast CT is often the only available or primary initial imaging modality, iAorta can help reduce delayed or missed diagnoses of AAS. (2) In clinical settings utilizing multiphase noncontrast and postcontrast CT protocols for AAS evaluation, iAorta’s high specificity and NPV on noncontrast CT scans can potentially help to avoid unnecessary contrast injection and reduce radiation doses from the postcontrast CTA.

The main strengths of iAorta are its validated high feasibility and reliability in real-world clinical settings. While several DL algorithms have been previously developed in this field, their performance varies notably between internal and external validation datasets, and none has been thoroughly evaluated in large-scale real-world prospective scenarios25,26,27,28. In such situations, the model’s low stability and biases in the training data notably limit its generalizability. By leveraging a large-scale, high-quality dataset with precise pathology annotations and using a refined effective two-stage training strategy, our model outperformed other state-of-the-art algorithms, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1. Our datasets primarily consisted of non-ECG-gated CT images and the noncontrast CT sourced from various scanning protocols, devices and populations. Although artifacts in the ascending aorta on non-ECG-gated CT images can lead to false-positive diagnoses of aortic dissection29,30 (as shown in Fig. 3c), iAorta effectively addresses these challenges and performs well. Moreover, previous studies have primarily focused on TAAD and TBAD alone, neglecting other critical conditions such as IMH and PAU. Recognizing the importance of these additional lesions is crucial for comprehensive coverage of complete AAS diagnosis and disease management. A key characteristic of AAS is the potential synchronous or metachronous appearance of these lesions in different aortic segments. These conditions, including TAAD, TBAD, IMH and PAU, are all time sensitive and can progress rapidly, with the risk of aortic rupture, especially during the initial stages of onset31,32. Our findings indicate that iAorta not only satisfactorily meets the critical clinical needs associated with AAS but also demonstrates strong potential for widespread application across noncontrast CT imaging with diverse patient scanning parameters, without requiring frequent adaptations or fine-tuning for future use.

iAorta has demonstrated promise as a tool to assist radiologists and emergency department clinicians by providing effective and interpretable visual cues of acute aortic lesions to support clinical decision-making. This feature is crucial in practice because visual clues help explain and validate AI system predictions, which is especially important for this acute life-threatening condition. Our visualization method is based on segmentation masks of the aorta and true lumen to generate the corresponding distance maps, making the presentation of lesion regions more spatially precise33, increasing radiologists’ confidence in evaluating and using the iAorta system’s results. In our study, differences in diagnostic accuracy among radiologists of various levels of experiences were evident, highlighting the challenges when detecting AAS on noncontrast CT scans. Because certain imaging features can be too subtle to notice without proper assistance, radiologists, particularly those with less experience, often struggle, and may even be unable, to identify AAS on noncontrast CT images. With the AAS flagging visual messages provided by our model/tool, radiologists’ diagnostic accuracy can be greatly improved. Unlike existing medical imaging-assisted diagnostic systems, iAorta incorporates an additional alert function. By prioritizing patients with a high probability of being AAS positive through timely alerts, the system enables radiologists to allocate their time and necessary attention to critical cases earlier (at the earliest possible), thereby optimizing the overall clinical workflow efficiently and effectively.

iAorta has the capability to locate lesion regions that may not be detected by radiologists when only using visual inspection. This ability probably stems from the DL model’s enhanced capacity to represent fine image features, enabling it to detect visually subtle but critical differences in pixel Hounsfield unit gradients34. In cases where the specific manifestations of AAS are not visually apparent on noncontrast CT imaging—especially common in younger patients, who may particularly benefit from the high sensitivity of AAS detection—iAorta’s capabilities are especially valuable. Visualized intimal flaps and thrombosed lumens appearing as high-attenuation areas are typical manifestations of AAS35. Older patients with AAS, usually with chronic hypertension, may exhibit atherosclerotic changes in the arterial wall, such as intimal thickening and calcification. Conversely, AAS in young individuals, often caused by connective tissue disorders, may result in fewer atherosclerotic changes36,37. Young patients with AAS, especially when asymptomatic, may be noncompliant with follow-up appointments and could deny their medical conditions. Due to concerns about CT imaging contrast material risks and medical costs, these patients may choose not to undergo aortic CTA initially or even refuse doing it in the ED. However, importantly, young patients with AAS often experience severe or rapid disease progression38. iAorta has demonstrated the potential to alleviate this diagnostic dilemma. If these patients have previously undergone routine noncontrast chest or abdominal CT scans, given the critical nature of AAS, it is advisable to proceed immediately with aortic CTA examination when radiologists cannot obtain consistent positive results—whether or not assisted by iAorta.

Our real-world clinical data highlight the critical role of noncontrast CT in the initial evaluation of patients presenting with acute chest pain in EDs across China, where the high cost and limited availability of CTA pose substantial barriers. Notably, the geographical distribution of tertiary hospitals in China varies substantially, with a large proportion of patients with AAS first seeking care at community hospitals or nontertiary centers9,39. At these clinical sites, CTA is often limited by technical and equipment constraints, making noncontrast CT the only feasible imaging test. Integrating iAorta with interhospital cloud platforms could expedite the referral of AAS patients from nontertiary to tertiary centers, ensuring timely and accurate treatment. Similarly, in low- and middle-income countries, the high cost and limited availability of iodinated intravenous contrast media further restrict access to CTA19,20. iAorta with its high sensitivity and NPV can help improve diagnostic confidence for excluding AAS from noncontrast CT. This enables CTA to be reserved for patients with a higher likelihood of AAS based on AI-driven evaluations of noncontrast CT scans. Moreover, delayed recognition of AAS remains a notable challenge. Even for TAAD, which often presents with typical symptoms, the median time from arrival at the ED to diagnosis is 4.3 h (ref. 5). The results from our prospective pilot deployment study demonstrated that, when iAorta was integrated into routine noncontrast CT workflows, the average diagnostic time for patients with AAS with atypical presentations was reduced to under 2 h. These findings clearly underscore the strong potential of iAorta to reduce delayed or missed diagnoses of AAS in settings where noncontrast CT remains the unavoidable initial or sole imaging test. Meanwhile, in settings where CTA is widely used, the application of iAorta does not imply the need to repeat or delay the contrast-enhanced CT scans. Many institutions (for example, in Hong Kong SAR) adopt multiphase CT protocols, including both noncontrast and postcontrast phases, as the standard protocol for AAS evaluation29. Noncontrast CT is often performed before contrast administration to enhance the detection of IMH and other subtle radiological findings. In our prospective pilot deployment study, a standard server equipped with a single NVIDIA 3090 graphics processing unit was capable of completing computing inference for a noncontrast CT scan case within 40 s. In such settings with the multiphase CT protocols, iAorta’s high specificity and high NPV on noncontrast CT could help avoid unnecessary contrast administration and reduce radiation exposure from postcontrast CT scans, particularly in low-risk patients (and possibly reduce healthcare costs).

Despite these remarkable results, there are several limitations of iAorta that are worth mentioning. First, our model was trained and validated on diverse cohorts within the Chinese population. Given the potential variability in aortic anatomy across different ethnicities, as well as differences in imaging equipment and acquisition protocols, further studies are needed to assess the model’s generalizability across populations and scanning platforms. Second, the model’s sensitivity for detecting PAU could be further improved. Integrating clinical symptoms and laboratory test results into a multimodal DL model has the potential to enhance its detection capabilities. Third, more patients in the early stages of AAS seek initial care at EDs at nontertiary centers or even community hospitals. We are planning to conduct another prospective, randomized, controlled trial extending to a broader range of medical centers and facilities to investigate the performance of iAorta in hospitals of various levels and its impact on enhancing the accuracy of the referral process. Also, through randomized controlled group comparisons, we can evaluate the time to definitive diagnosis and survival outcomes of AAS patients with and without iAorta deployment.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that iAorta is a highly valuable tool for critical emergency decision-making, facilitating earlier and more accurate diagnosis of AAS through early warning, thereby enabling timely and appropriate patient treatment. Furthermore, iAorta may be extended to show good potential in detecting other life-threatening causes of chest pain beyond aortic conditions, such as non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism and esophageal rupture8. Increased availability and improved scanning technology have led to drastic increases in CT utilization, particularly in the ED40,41,42. The integration of iAorta and its potential variations could offer valuable benefits into the clinical utility of noncontrast CT in the early and accurate diagnosis and management of high-risk patients presenting with acute chest pain. Meanwhile, iAorta achieved excellent and robust specificity in several realistic and large-scale clinical settings. This demonstrates that AI technology has the potential to make noncontrast CT an effective rule-out tool, standardize decision-making for the use of advanced imaging in life-threatening conditions, and balance the risks of misdiagnosis and overtesting. By leveraging AI technology to aid in the interpretation of CT scans, healthcare providers may be better equipped to promptly identify and address life-threatening causes of patients with acute chest pain, improve final patient outcomes and optimize the clinical decision-making in ED scenarios.

Methods

Ethics approval

Data collection protocols and the use of images, radiological reports and clinical information were approved by the ethical committee of each participating hospital. Informed consent was waived for retrospectively collected CT images and clinical information, and written informed consent was obtained from patients whose CT examinations, clinical information and follow-up records were prospectively collected. All procedures followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design and study population

To train the model to learn the image features of AAS on noncontrast CT, we collected data from 3,350 consecutive patients who underwent aorta CTA scans, including both arterial and noncontrast phase CT series, at FAHZU (Zhejiang, China) between 2016 and 2020 as the internal training cohort. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Supplementary Section 1.1. The internal training cohort consisted of 1,265 patients with AAS (296 with TAAD, 341 with TBAD, 321 with IMH and 307 with PAU) and 2,085 patients without AAS. The baseline demographic information and image characteristics of noncontrast phase CT series are summarized.

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of the model and its interpretability for radiologists, we collected data from 2,287 consecutive patients who underwent aorta CTA at FAHZU between 2021 and 2022 as the internal validation cohort under the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. The internal validation cohort consisted of 795 patients with AAS (188 with TAAD, 248 with TBAD, 203 with IMH and 156 with PAU) and 1,492 patients without AAS. We ensured that the internal validation dataset did not overlap with the internal training dataset, and the radiologists participating in the reader study had not previously reviewed the data from the internal validation dataset.

We enrolled seven independent multicenter cohorts for external validation to assess the generalizability and robustness of the developed model. The external multicenter validation cohorts were collected from seven centers across China: one top medical center in southern China (external validation cohort 1, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, NDTH, 3,287 patients), one top medical center in northern China (external validation cohort 2, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, SPH, 2,351 patients) and five regional medical centers in Zhejiang Province (external validation cohort 3, Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province, TZH, 1,567 patients; external validation cohort 4, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, FAHWMU, 4,574 patients; external validation cohort 5, Ningbo No. 2 Hospital, N2H, 2,369 patients; external validation cohort 6, Quzhou People’s Hospital, QPH, 3,015 patients; external validation cohort 7, Shaoxing Central Hospital, SCH, 1,300 patients). The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria were consistent with those described above, and the process of enrollment for each cohort is described in Supplementary Section 1.3 (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). The multicenter validation cohort, consisting of noncontrast CT scans of 6,495 patients with AAS (1,343 with TAAD, 1,905 with TBAD, 1,718 with IMH and 1,529 with PAU) and 11,968 patients without AAS, was used for independent validation when no model parameters were tuned or adjusted.

To further explore the model’s robustness across various noncontrast CT protocols from real-world emergency, we performed a two-round, large-scale, real-world, retrospective study (RW1 and RW2) on three medical centers in Zhejiang Province, China. The original model and the upgraded model were evaluated in the RW1 and RW2 cohorts, respectively. Patients who presented to the ED with acute chest pain and underwent CT scans (for example, noncontrast chest CT, noncontrast abdominal CT, pulmonary CTA, coronary CTA, esophageal CT, lumbar CT or thoracic CT) covering part of the aortic region based on the initial suspicion of other acute diseases were enrolled in this study. Note that some patients underwent multiple CT examinations with different protocols. We collected the noncontrast phase CT series images from the various CT examinations mentioned above. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Supplementary Section 4.1 (Supplementary Figs. 5–9). The RW1 cohort comprised 23,094 noncontrast CT scans (44 AAS images, 23,050 non-AAS images) from 20,832 consecutive patients with acute chest pain at the FAHZU (32 AAS individuals, 20,800 non-AAS individuals). The RW2 cohort comprised 122,107 noncontrast CT scans (118 AAS images, 121,989 non-AAS images) of 116,693 consecutive individuals with acute chest pain at FAHZU, QPH and SCH (89 AAS individuals, 116,604 non-AAS individuals).

To further evaluate the implementation of iAorta in the realistic clinical settings, we conducted a two-stage, prospective and multicenter study. Patients who presented to the ED with acute chest pain symptoms and underwent CT scans covering part of the aortic region based on the initial suspicion of other acute diseases were enrolled in this study. We collected the noncontrast phase series images from the various CT examinations. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Supplementary Section 5.1 (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). (1) The comparative cohort comprised 14,436 noncontrast CT scans (14 AAS images, 14,422 non-AAS images) of 13,846 consecutive patients (11 AAS patients, 12,884 non-AAS patient) with acute chest pain at the FAHZU, QPH and SCH. (2) The deployment cohort contained 16,054 noncontrast CT scans (22 AAS images, 16,032 non-AAS images) of 15,584 consecutive patients (22 AAS patients, 15,562 non-AAS patients) with acute chest pain at Shanghai Changhai Hospital, SHCH.

The CT images were retrieved from the PACS of each participating hospital and stored in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. For all aorta CTA scans in the training and validation datasets, both arterial and noncontrast phase CT series were included. The aorta CTA scan protocol started with a noncontrast CT scan from the thoracic inlet to the pubic symphysis, covering the entirety of the aorta. Thereafter, the arterial phase CT scan was performed over the same area as the systemic arterial phase scan. Due to the small-time gap between the two scans, the anatomical morphology depicted in the noncontrast phase series differed slightly from that observed in the arterial phase series taken ‘simultaneously’. For the data in the clinical practicality study, noncontrast phase series were retrieved from various CT scans.

Diagnostic criteria

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the AAS detection model, patients were initially categorized into non-AAS or AAS groups. Within the AAS category, patients were further classified into four subgroups based on the subtype of AAS as per the 2022 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines1: TAAD, TBAD, IMH and PAU. Patient cases presenting with a PAU alongside IMH were categorized under the IMH group, due to the higher risk associated with IMH compared with isolated PAUs. This classification approach facilitated a more precise assessment of the model’s ability to identify various emergent cases.

In the training and validation cohorts, corresponding arterial series CT images from the same aortic CTA were used as the gold standard to determine the presence of AAS. Each image was assigned a case-level diagnostic label, including the disease subtype, through a tiered annotation system. Moreover, two additional pixel-level segmentation labels were provided for the training datasets. The tiered annotation system consists of three cascades of trained radiologists at different levels for the verification and correction of CT image pixel-level labels. The details are described in Supplementary Section 1.4.

For both the retrospective real-world study and prospective multicenter study, patients’ diagnoses were confirmed through the diagnostic data obtained during the ED visit and during the 14-day follow-up period. Details of the diagnosis standards are described in Supplementary Sections 4.2 and 5.2, respectively.

The development of the DL model and iAorta system

The DL model consists of two stages (Extended Data Fig. 2) and was trained using supervised DL. Given the input of a noncontrast CT scan, we localized the aorta at the coarse stage and then detected possible AAS at the fine stage. The output of model consists of three components: the classification of the potential AAS with probabilities, the segmentation mask of the aorta wall and true lumen, and the activation result representing the potential lesion region in each CT slice.

The aim of the coarse processing stage is to localize the aorta. In this stage, we trained a lightweight nnU-Net43,44 to segment the whole aorta from the input noncontrast CT scan. The aim of the fine processing stage was to detect the potential AAS lesion. The network is based on a multitask learning strategy45. Specifically, we trained a joint segmentation and classification network to simultaneously segment the aortic wall and true lumen and classify the patient-level abnormalities, that is, AAS or non-AAS. The network output consists of the probabilities of AAS, the segmentation mask of the aorta wall and true lumen, and the activation map result indicating the potential lesion region for enhanced reader interpretability. The activation map result can indicate the potential lesion region spatially for enhanced slice-level and patient-level interpretability. Moreover, the network is supervised by a combination of focal loss46, Dice loss47 and voxel-wise cross-entropy loss48. More details on the training and inference of two stages are given in Supplementary Sections 2.2 and 2.3. After the RW1 analysis, we collected both false-positive and false-negative noncontrast CT data from the RW1 cohort. This process aligns with machine learning strategies referred to as hard example mining49 and incremental learning50. The evolved model was subsequently subjected to evaluation on the RW2 cohort. Details regarding the collection and annotation of these updated training datasets, along with the fine-tuning protocol, are described in Supplementary Section 4.4 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

We have developed a browser–server collaborative early warning system designed for rapid and accurate detection of AAS in two prospective real-world clinical settings. By integrating a noncontrast CT phase selection/identification tool, we developed the model and a warning pop-up plugin, so that the system can process and analyze large amounts of patient data in real time, enabling radiologists to get timely alerts and make informed diagnosis and intervention. More details are given in Supplementary Section 2.7. Please note that we have provided complementary access to the browser interface of our iAorta system (https://iaorta.medofmind.com/; Extended Data Fig. 5). The browser interface provides an open-access CT image database containing typical cases, which may be a useful resource for training radiologists as well as familiarizing researchers in the field of analyzing aortic diseases and AI-assisted medical imaging.

Model and system evaluation

After training the DL model, we conducted a multicenter validation study, a reader study and a large-scale real-world retrospective study to evaluate the model’s performance and its potential benefit for the current existing clinical workflows. After the real-world retrospective study, the DL model is developed and upgraded to iAorta, a browser–server collaborative early warning system, to enhance its application in real-world emergency clinical settings. We then conducted a prospective multicenter study to evaluate the implementation of iAorta in the realistic clinical setting.

Stage I—multicenter model validation

We used eight independent multicenter validation patient cohorts to evaluate the model performance. Our model is formulated as a two-class classification task to distinguish between AAS and non-AAS. Having AAS is defined as the ‘positive’ class for calculating AUC, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy and F1 score. In addition, we calculated the diagnosis sensitivity of model in cases of four AAS subtypes (including TAAD, TBAD, IMH and PAU) separately because the disease progression and untreated mortality differed notably among the four subtypes.

Stage II—reader study on the noncontrast CT

We recruited a total of 11 radiologists with three levels of clinical specialty experience (specialty experts, board-certified general radiologists and medical trainees) to compare the model performance with that of radiologists. This test was conducted in two phases or periods using noncontrast CT images from the internal validation dataset. Phase 1 took place over a 16-week period (6 January 2023 to 28 March 2023) and was designed to evaluate the performance of the radiologists alone. During phase 1, 11 radiologists interpreted scrambled noncontrast CT images on the edge-cloud collaborative platform mentioned above, while the widget displaying the AI results was intentionally set to be inactive. Therefore, the radiologists were blinded to the AI results in phase 1. After a 2-month desensitization period, participating radiologists previously interpreting noncontrast CT images were retained and trained to use our model on the online platform with the widget activated, but they were not informed of the detection accuracy of our model. Phase 2 spanned a 16-week period (7 July 2023 to 10 October 2023) and was designed to evaluate the performance of the clinicians assisted with AI image interpretation tool. The AI results were displayed in a visual interface concurrently during the image diagnostic evaluation. The details are provided in Supplementary Section 3.

Stage III—large-scale, real-world, retrospective study

To explore the robustness across various noncontrast CT protocols in real-world emergency scenarios, we retrospectively collected four patient cohorts with acute chest pain symptoms presenting to the EDs in three hospitals and conducted two rounds of real-world evaluation (RW1 and RW2). First, the model was evaluated on RW1. Then, after analyzing the reasons for bad cases based on the evaluation results, we incorporated the false-positive and false-negative cases from RW1 and upgraded our model by incremental learning techniques. Finally, the upgraded model was evaluated on RW2. At the same time, the original model was also evaluated on RW2 as a control group. As timely diagnosis of AAS is crucial for improving prognosis, we evaluated the reduction in missed and incorrect diagnoses, which serves as a key indicator of our model’s potential benefit.

Stage IV—prospective multicenter study

To further evaluate the feasibility of iAorta in realistic real-world clinical settings, we prospectively conducted both a comparative study and a pilot deployment study. We developed a real-time warning system, iAorta, which is integrated into the existing clinical workflow on PACS.

The prospective comparative study is a prospective, observational study. We recruited two groups of radiologists to explore the potential improvement in diagnostic performance and the reduction in final definitive diagnosis time when iAorta is integrated into the existing clinical workflow, as compared with the original clinical workflow. Each group included board-certified general radiologists per shift for the initial report and specialty experts for the final reviewing report. Group A independently reviewed the patients’ CT scans in a sequential manner under the current clinical workflow using the local PACS and provided the final reviewing report to guide subsequent patient management. This process generates two independent diagnostic records: one for the IR radiologist’s diagnosis and the other for the RR radiologist’s diagnosis, for each patient CT scan. Meanwhile, group B reviewed the images with the assistance of a locally deployed iAorta system. The images are automatically fed into iAorta system, which then produces AI-based results. If the AI detects any abnormalities, both the IR radiologists and the RR radiologists receive subsequential pop-up message alerts, prompting them to prioritize the review of the AI-flagged (AAS-positive) patient scan. After reviewing the AI results, the AAS-related diagnosis is recorded. This process yields three independent diagnostic records for each image: the IR radiologist’s diagnosis (aided with AI), the RR radiologist’s diagnosis (aided with AI) and the AI-computed results. In addition, we recorded the patients’ arrival time to the hospital, the time of initial diagnosis and final definitive diagnosis, the time-to-results for laboratory testing and the time of ordering the CT examination, performing the CT scan, the initial report and the final report. Here, we defined the time to the correct diagnostic pathway for patients with AAS as the period from the patient’s arrival in the ED until AAS was mentioned as a positive possibility in their noncontrast CT imaging report via AI associated with a recommendation for the aortic CTA examination, or the point at which they were advised to undergo conclusive diagnostic imaging for other reasons by clinicians.

The prospective pilot deployment study is an ongoing, single-arm, prospective study (20 December 2024 to 28 Febuary 2025). We integrated the iAorta system into the current pilot clinical daily routine and utilized AI-assisted or AI-alerted electronic imaging reports to guide subsequent patient management. We also recorded the patients’ arrival time to the hospital, the time of initial diagnosis and final definitive diagnosis, the time-to-results for laboratory testing and the time of ordering the CT examination, performing the CT scan, the initial report and the final report. We analyzed the time from the initial ED presentation to definitive diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the means with standard deviations, while frequencies and percentages are noted to summarize classification variables. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of iAorta and radiologists for the detection of AAS were evaluated by calculating the 95% CIs using the Clopper–Pearson method. We used the ROC curves as the main quantitative measure to demonstrate and evaluate the performance of the DL algorithm to discriminate patients with AAS from normal controls. ROC curves were generated by plotting the proportion of true positive cases (sensitivity) against the proportion of false-positive cases (1 − specificity) by varying the predictive probability threshold. A larger AUC indicated better diagnostic performance. The significance test comparing the AUCs was conducted using the Delong test. All the statistical tests were two-sided with a statistical significance level of 0.05. We used the scikit-learn package (version 1.0.2) to compute the evaluation metrics.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The sample data and an interactive demonstration are available at https://iaorta.medofmind.com/. The remaining datasets used in this study are currently not permitted for public release by the respective institutional review boards (IRBs). Data requests pertaining to the study may be made to the first author (Yujian Hu; huyujian@zju.edu.cn). Access will be granted pending IRB approval and a signed data-use agreement, and will be restricted to noncommercial academic use only. All data provided were anonymized to protect the privacy of the patients who participated in the studies, in line with applicable laws and regulations. Requests will be processed within 6 weeks.

Code availability

The code used to implement our model relies on internal tools and infrastructure, is protected under patent application CN 202311181343.8, and therefore cannot be publicly released. All experiments and implementation details are described in sufficient detail in the Methods and Supplementary Information (‘Details of model development’) sections to support replication with nonproprietary libraries. Several major components of our work are available in open-source repositories: PyTorch (https://pytorch.org/) and nnU-NetV1 (https://github.com/MIC-DKFZ/nnUNet/tree/nnunetv1).

References

Isselbacher, E. M. et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, e223–e393 (2022).

Mazzolai, L. et al. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur. Heart J. 45, 3538–3700 (2024).

Hagan, P. G. et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA 283, 897–903 (2000).

Strayer, R. J. et al. Screening, evaluation, and early management of acute aortic dissection in the ED. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 8, 152–157 (2012).

Harris, K. M. et al. Correlates of delayed recognition and treatment of acute type A aortic dissection: the IRAD experience. Circulation 124, 1911–1918 (2011).

Tsai, T. T., Trimarchi, S. & Nienaber, C. A. Acute aortic dissection: perspectives from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 37, 149–159 (2009).

Tsai, T. T., Nienaber, C. A. & Eagle, K. A. Acute aortic syndromes. Circulation 112, 3802–3813 (2005).

Gulati, M. et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain. Circulation https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001029 (2021).

Salmasi, M. Y. et al. The risk of misdiagnosis in acute thoracic aortic dissection: a review of current guidelines. Heart 106, 885–891 (2020).

Seo, M. J., Lee, J. H. & Kim, Y.-W. A novel tool for distinguishing type A acute aortic syndrome from heart failure and acute coronary syndrome. Diagnostics 13, 3472 (2023).

Zuin, G. et al. ANMCO-SIMEU Consensus Document: in-hospital management of patients presenting with chest pain. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 19, D212–D228 (2017).

Carroll, B. J. et al. Imaging for acute aortic syndromes. Heart 106, 182–189 (2020).

Mettler, F. A. Jr. et al. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology 248, 254–263 (2008).

Lovy, A. J. et al. Preliminary development of a clinical decision rule for acute aortic syndromes. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 31, 1546–1550 (2013).

Nazerian, P. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the aortic dissection detection risk score plus D-dimer for acute aortic syndromes: the ADvISED prospective multicenter study. Circulation 137, 250–258 (2018).

Yip, W. & Hsiao, W. C. The Chinese health system at a crossroads. Health Aff. 27, 460–468 (2008).

Hou, J. & Ke, Y. Addressing the shortage of health professionals in rural China. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 4, 327–328 (2015).

Chinese Medical Association, et al. Guideline for primary care of chest pain (2019). Chin. J. Gen. Pract. 18, 913–919 (2019).

Bertoldi, E. G. et al. Cost-effectiveness of anatomical and functional test strategies for stable chest pain. BMJ Open 7, e012652 (2017).

Peix, A. Functional versus anatomical approach in stable coronary artery disease patients. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 24, 518–522 (2017).

Otani, T. et al. Potential of unenhanced computed tomography as a screening tool for acute aortic syndromes. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 10, 967–975 (2021).

Bonaca, M. P. & Reece, T. B. Novel views on finding an old foe: non-contrast computed tomography in the diagnosis of acute aortic syndromes. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 10, 976–977 (2021).

Mussa, F. F. et al. Acute aortic dissection and intramural hematoma: a systematic review. JAMA 316, 754–763 (2016).

Kurabayashi, M. et al. Diagnostic utility of unenhanced computed tomography for acute aortic syndrome. Circ. J. 78, 1928–1934 (2014).

Guo, Y. et al. Non-contrast CT-based radiomic signature for screening thoracic aortic dissections: a multicenter study. Eur. Radiol. 31, 7067–7076 (2021).

Hata, A. et al. Deep learning algorithm for detection of aortic dissection on non-contrast-enhanced CT. Eur. Radiol. 31, 1151–1159 (2021).

Yi, Y. et al. Advanced warning of aortic dissection on non-contrast CT: combining deep learning and morphological characteristics. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 762958 (2022).

Xiong, X. et al. A cascaded multi-task generative framework for detecting aortic dissection on 3-D non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 26, 5177–5188 (2022).

Vardhanabhuti, V. et al. Recommendations for accurate CT diagnosis of suspected acute aortic syndrome. Br. J. Radiol. 89, 20150705 (2016).

Writing Group Members et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of thoracic aortic disease. Circulation 121, e266–e369 (2010).

Vilacosta, I. et al. Acute aortic syndrome revisited. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78, 2106–2125 (2021).

Booher, A. M. et al. The IRAD classification system for characterizing survival after aortic dissection. Am. J. Med. 126, 768–775 (2013).

Lau, B., Sprunk, C. & Burgard, W. Improved updating of Euclidean distance maps and Voronoi diagrams. Proc. IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. Intell. Robot. Syst. 281, 286 (2010).

Balaur, E. et al. Colorimetric histology using plasmonically active microscope slides. Nature 598, 65–71 (2021).

Castaner, E. et al. CT in nontraumatic acute thoracic aortic disease: typical and atypical features and complications. Radiographics 23, S93–S110 (2003).

Erbel, R. et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases. Kardiol. Pol. 72, 1169–1252 (2014).

Nienaber, C. A. & Eagle, K. A. Aortic dissection: from etiology to diagnostic strategies. Circulation 108, 628–635 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Age-related differences in acute aortic dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 75, 473–483.e4 (2022).

Liu, L. W. et al. Effectiveness of chest pain center accreditation on hospital outcomes in acute aortic dissection. Mil. Med. Res. 11, 62 (2024).

Bellolio, F. et al. Increased computed tomography utilization in the emergency department and its association with hospital admission. West. J. Emerg. Med. 18, 835–845 (2017).

Berdahl, C. T., Vermeulen, M. J., Larson, D. B. & Schull, M. J. Emergency department computed tomography utilization in the United States and Canada. Ann. Emerg. Med. 62, 486–494.e3 (2013).

Greer, C., Williams, M. C., Newby, D. E. & Adamson, P. D. Role of computed tomography cardiac angiography in acute chest pain syndromes. Heart 109, 1350–1356 (2023).

Isensee, F. et al. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 203–211 (2021).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (eds Navab, N. et al.) 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, Q. A survey on multi-task learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34, 5586–5609 (2021).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2980–2988 (2017).

Milletari, F., Navab, N. & Ahmadi, S. A. V-Net: fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proc. International Conference on 3D Vision 565–571 (2016).

Ruby, U. & Yendapalli, V. Binary cross entropy with deep learning technique for image classification. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, (2020).

Shrivastava, A., Gupta, A. & Girshick, R. Training region-based object detectors with online hard example mining. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 761–769 (2016).

Van de Ven, G. M., Tuytelaars, T. & Tolias, A. S. Three types of incremental learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 1185–1197 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the investigators and participants in this study. This study was supported by the Technical Innovation key project of Zhejiang Province (2024C03023) to H.Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Hu, Y. Xiang, Y.-J.Z., L.L. and H.Z. designed the study. Y. Xiang, Yangyan He, D. Lang, S.Y., X.D., Y. Xu, Gaofeng Wang, J.H., W.Z., X.W., D. Li, Q.Z., Z. Li, C.Q., Z.W., Yunjun He, C.T., Y.Q., Z. Lin, X. Zhou, Yuan He, Z.Y., X. Zhou, R.F., R.C., X.L. and Y.B. collected and organized data. W.G., J.X., J.Z., T.C.W.M. and Z.L. carried out the data preprocessing. Y.-J.Z. and M.X. developed the AI model and the computational framework. Yangyan He, D. Lang, S.Y., C.D., L.H. and W.X. analyzed and interpreted the data. W.G., C.S., Guofu Wang, L.W. and H.Z. carried out the clinical deployment. Y. Hu, Y. Xiang and Z.D. carried out the statistical analysis. Y. Hu, Y. Xiang, Y.-J.Z. and M.X. wrote and revised the paper. M.K.K., L.L., Z.H., M.X. and H.Z. provided critical comments and reviewed the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Alibaba Group has filed for patent protection (application number CN 202311181343.8) on behalf of Y.-J.Z., M.X. and L. Lu for the work related to the methods of detection of acute aortic syndrome on noncontrast CT. Y.-J.Z., W.G., J.Z., T.C.W.M., Z.L., L.L. and M.X. are employees of Alibaba Group and own Alibaba stock as part of the standard compensation package. All other authors have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Eduardo Bossone, Christoph Nienaber, Konrad Pieszko and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Lorenzo Righetto, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Patient and data sources of model development, multi-center model validation (stage I), reader study (stage II), large-scale real-world retrospective study (stage III), and prospective multi-center study (stage IV).

Data source includes different field of views (FOVs) and z-axis coverage in aortic CTA, coronary CTA, non-contrast chest CT, pulmonary CTA, rib CT, non-contrast abdominal CT, and lumbar spine CT.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Network architecture.

(Top) Overview. Our deep learning framework consists of two stages: aorta localization using a lightweight U-Net, and abnormality detection using a multi-task CNN. (Bottom) Architectures of the lightweight U-Net and multi-task CNN. The features extracted from encoder are used for abnormal and normal classification. Decoder A and T are designed for the segmentation of aorta and true lumen, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Interpretable results of iAorta in four subtypes of AAS and two artifact cases.

The two colors in the slice sequence (arranged by spatial location) represent two classes of slice-level prediction including AAS (yellow) and non-AAS (green). The slice activation map indicates the voxel-level localization of AAS. AAS, acute aortic syndrome; TAAD, Stanford Type A dissection; TBAD, Stanford Type B dissection; IMH, intramural hematoma; PAU, penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Flowchart illustrating the potential benefits for patients with Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS) who were initially suspected to have other acute diseases in the retrospective real-world study (stage III), compared to the current clinical workflow.

a. A patient with lower back pain was initially suspected to have lumbar disc protrusion and underwent clinical investigations, including lumbar spine CT and non-contrast chest CT. b. A patient with abdominal pain was initially suspected to have acute gastroenteritis, underwent clinical investigations including a non-contrast abdominal CT, and was discharged from the ED. Four days later, he returned to the ED with worsening symptoms and underwent a non-contrast chest CT. Our model could have detected AAS during the first visit. c. A patient with abdominal pain was suspected to have a chemotherapy drug reaction and underwent clinical investigations, including non-contrast abdominal CT and pulmonary CTA. Before a definitive diagnosis, the patient experienced cardiopulmonary arrest. iAorta system could potentially save the patient’s life.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Flowchart describing the process of the seamless integration of iAorta into the existing clinical workflow.

PACS, picture archiving and communication system; RIS, radiology information system.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion, Figs. 1–11 and Tables 1–10.

Supplementary Video 1

Supplementary Video 1.

Rights and permissions