Abstract

Scalable, pragmatic approaches to obesity implemented in primary care have the potential to curtail population weight gain. In a stepped-wedge cluster-randomized pragmatic trial in the state of Colorado, USA, 56 primary care clinics were randomly assigned to three clusters with staggered start dates for a one-way crossover from usual care to the intervention phase. The intervention (PATHWEIGH) included three components: (1) health system primary care leadership endorsement; (2) an electronic health record-driven care process designed to prioritize, facilitate and expedite weight management; and (3) implementation strategies to support use of the care process and educate clinicians on obesity treatment. The coprimary outcomes were average patient weight loss at 6 months and weight loss maintenance from 6 months to 18 months. In total, 274,182 adults with a body mass index ≥25 kg m2 had at least 2 measured weights in one of the clinics between March 2020 and March 2024. A counterfactual analysis comparing differences in weight between the intervention and usual care suggests that PATHWEIGH decreased average weight by 0.29 kg (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.27 kg, 0.32 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P < 0.001) and 0.28 kg (95% CI: 0.26 kg, 0.31 kg) from 6 months to 18 months (P < 0.001) for a total difference of 0.58 kg (95% CI: 0.54 kg, 0.61 kg; P < 0.001). PATHWEIGH increased the likelihood of receiving weight-related care during the intervention (OR = 1.23; 95% CI 1.16, 1.31; P < 0.001). The intervention was associated with greater weight loss for those receiving weight-related care (adjusted difference of 2.36 kg over 18 months; 95% CI: 2.31 kg, 2.42 kg, P < 0.001), and weight gain was mitigated in the intervention even when patients did not receive weight-related care (adjusted difference of 0.32 kg over 18 months, 95% CI: 0.30 kg, 0.35 kg; P < 0.001). Thus, PATHWEIGH is a pragmatic, scalable approach showing favorable impact on population weight. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04678752.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Obesity has been recognized as a major health issue in Westernized countries for more than three decades. Now, obesity is a greater contributor to disability-adjusted life-years and death than undernutrition in more than 200 countries around the world1. Despite its increasing acceptance as an independent disease, no widescale strategy has reduced the prevalence of obesity in any country2. Even in medical settings, obesity remains largely undiagnosed3 and untreated4.

The reasons why weight management is rarely prioritized in clinical settings are extensive and complex. Healthcare providers cite lack of time, education and resources, as well as competing issues, as the leading reasons why obesity is not prioritized; in addition, poor reimbursement and lack of effective tools are also widely cited5,6. Furthermore, weight loss is widely perceived as the responsibility of the patient7. This mindset influences clinician opinion and downstream insurance coverage ultimately restricting access to the most effective treatments8. Lastly, pervasive stigma and bias surrounding the medical treatment of obesity contributes to inertia among payors, clinicians and patients.

To address these barriers, our study leveraged existing resources and workflows to engage major stakeholders, including patients, clinicians and the health system at large, to assess patient weight trajectories over time in a stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial. To this end, we implemented and assessed a health system primary care leadership-endorsed care process (‘PATHWEIGH’) across primary care clinics in the state of Colorado, USA, to prioritize, facilitate and expedite weight management. This included customization of the electronic health record (EHR) and implementation strategies to support use of the care process and educating clinicians on obesity treatment. Our objective was to determine whether the implementation of PATHWEIGH had greater effectiveness on patient weight loss and weight maintenance compared with usual care.

Results

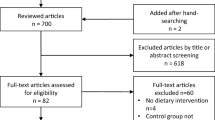

The intention-to-treat population

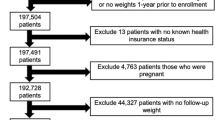

Data handling is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 574,004 unique adult patients were seen in 1 of 56 clinics between 17 March 2020 and 16 March 2024. Of these, 274,182 had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg m2 with at least two weight measurements recorded in the EHR and are included in the primary outcome analysis assessing change in weight. Of these patients, 189,227 were first weighed during usual care and 84,955 were first weighed in the intervention (147,455 weighed in usual care were also weighed in the intervention). The demographics and health metrics of patients included in this analysis are shown in Table 1 and are highly representative of the demographics of adults residing in Colorado. Supplementary materials provide additional details, including participating clinics (Extended Data Table 1), an operational definition of the Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS; Extended Data Table 2), captured weight-related comorbidities (Extended Data Table 3) and modeling outputs for Fig. 2a,b (Extended Data Tables 4 and 5).

a,b, Predicted weight trajectories for eligible patients with a measured weight in the usual care (blue line) and intervention (red line) phases from 0 month to 6 months and 6 months to 18 months from their first weight regardless of whether they received discernable weight-related care in the ITT sample (a), and who received weight-related care in the usual care (blue line) or intervention phase (pink line), and those who never received weight-related care in the usual care (purple line) or intervention phase (green line) in the prespecified secondary analysis (b). The two-piece (0–6 months and 6–18 months) solid lines are predicted weights for a hypothetical average patient during follow-up with 95% prediction intervals in gray.

Coprimary outcomes comparing usual care and the intervention in eligible patients

The intervention (PATHWEIGH) included 3 components: (1) health system primary care leadership endorsement, (2) an EHR-driven care process designed to prioritize, facilitate and expedite weight management and (3) implementation strategies to support use of the care process and educate clinicians on obesity treatment. The coprimary outcomes were average patient weight loss at 6 months and weight loss maintenance from 6 months to 18 months. From the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, the average time these patients spent in usual care was 9.1 months and the average time these patients spent in the intervention phase was 13.7 months. Model-adjusted predicted average weight increased by 0.29 kg (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.27 kg, 0.32 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P < 0.001) and by 0.18 kg (95% CI: 0.15 kg, 0.21 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) for an average total weight gain of 0.47 kg (95% CI: 0.45 kg, 0.50 kg) in the usual care phase (P < 0.001). Model-adjusted predicted weight decreased by 0.00 kg (95% CI: −0.03 kg, 0.03 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P = 0.98) and by 0.10 kg (95% CI: 0.07 kg, 0.12 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) for an average total weight loss of 0.10 kg (95% CI: 0.07 kg, 0.13 kg) in the intervention phase (P < 0.001). A counterfactual analysis comparing differences in weight between the intervention and usual care suggests that the intervention decreased average weight by 0.29 kg (95% CI: 0.27 kg, 0.32 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P < 0.001) and 0.28 kg (95% CI: 0.26 kg, 0.31 kg) from 6 months to 18 months (P < 0.001) for a total difference of 0.58 kg (95% CI: 0.54 kg, 0.61 kg) (P < 0.001), showing the intervention’s ability to eliminate the population weight gain observed in usual care (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Table 4).

Approximately 25% of eligible patients received discernable care for their weight at least once during the trial (in one phase or both; Table 1). Of these patients, 50,482 were first weighed during usual care and 18,900 were first weighed in the intervention (44,215 weighed in usual care were also weighed in the intervention). Notably, a higher proportion of patients who received discernable care for their weight (versus those who did not) were commercially insured (67% versus 62%) women (61% versus 51%) with a higher average BMI (36 kg m−2 versus 30 kg m−2) at their initial weight measurement (Table 1). Results from the generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic model indicated that the intervention increased the likelihood of a patient receiving discernable care for their weight by 23% (odds ratio = 1.23 versus usual care; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.31; P < 0.001).

Prespecified secondary analysis among patients identified as having received discernable care for their weight

Among patients receiving discernable care for their weight during the study period, the average time these patients spent in usual care was 11.3 months and the average time these patients spent in the intervention phase was 32 months. Counterfactual analysis model-adjusted predicted average weight decreased by 0.06 kg (95% CI: 0.00 kg, 0.12 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P = 0.037) and by an additional 0.39 kg (95% CI: 0.35 kg, 0.43 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) for a total weight loss of 0.45 kg (95% CI: 0.40 kg, 0.49 kg) (P < 0.001) for those receiving weight-related care during usual care. Model-adjusted predicted average weight decreased by 0.88 kg (95% CI: 0.81 kg, 0.95 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P < 0.001) and by an additional 1.30 kg (95% CI: 1.25 kg, 1.35 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) for a total weight loss of 2.18 kg (95% CI: 2.12 kg, 2.24 kg) (P < 0.001) for those receiving weight-related care during the intervention phase. The adjusted difference between usual care and the intervention was 1.73 kg more weight loss over 18 months in the intervention for those receiving weight-related care (95% CI: 1.68 kg, 1.78 kg, P < 0.001; Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 5).

Prespecified secondary analysis among patients identified as having never received discernable care for their weight

Among patients never receiving discernable care for their weight during the study period, 138,745 were first weighed during usual care and 66,055 were first weighed in the intervention phase (103,240 weighed in usual care were also weighed in the intervention; Table 1). The average time these patients spent in usual care was 9.56 months, and the average time these patients spent in the intervention phase was 26.9 months. Counterfactual analysis model-adjusted predicted average weight increased by 0.29 kg (95% CI: 0.26 kg, 0.32 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P < 0.001) and by an additional 0.26 kg (95% CI: 0.23 kg, 0.29 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) for a total weight gain of 0.55 kg (95% CI: 0.52 kg, 0.58 kg) (P < 0.001) during usual care. Model-adjusted predicted average weight increased by 0.08 kg (95% CI: 0.045 kg, 0.11 kg) from the first weight to 6 months later (P < 0.001) and by an additional 0.10 kg (95% CI: 0.07 kg, 0.14 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) for a total weight gain of 0.18 kg (95% CI: 0.15 kg, 0.22 kg) (P < 0.001) during the intervention phase. The adjusted difference of 0.32 kg over 18 months in usual care versus intervention (95% CI: 0.30 kg, 0.35 kg; P < 0.001) is the amount of intervention-mitigated weight gain even when patients did not receive weight-related care (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 5).

Weight trajectories in those who did versus did not receive weight-related care

An associative counterfactual analysis comparing the weight trajectories of patients who received discernable care for their weight and those who did not indicated that these two subpopulations have different weight trajectories. The model-adjusted difference in weight for those with an initial visit in usual care who received weight-related care weighed was 0.35 kg (95% CI: 0.30 kg, 0.40 kg) lower at 6 months (P < 0.001) and an additional 0.65 kg (95% CI: 0.63 kg, 0.68 kg) lower from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) than would be expected without weight-related care. The adjusted difference of 1.00 kg over 18 months (95% CI: 0.96 kg, 1.04 kg; P < 0.001) represents the difference in weight for those who did versus did not receive weight-related care during usual care (Fig. 2b). The model-adjusted difference in weight for those with an initial visit in the intervention phase who received weight-related care weighed was 0.96 kg (95% CI: 0.89 kg, 1.03 kg) less at 6 months (P < 0.001) and an additional 1.41 kg (95% CI: 1.36 kg, 1.45 kg) from 6 months to 18 months later (P < 0.001) than would be expected without weight-related care. The adjusted difference of 2.37 kg over 18 months (95% CI: 2.33 kg, 2.40 kg; P < 0.001) represents the difference in weight for those who did versus did not receive weight-related care during the intervention phase (Fig. 2b).

Delivery of weight-related care

Trackable weight-related care included referrals, performance of a bariatric procedure and patient acknowledgement that an anti-obesity medication was actively being used. Clinician counseling on lifestyle modification was not trackable, but rather presumed when the clinician used a weight-related International Classification of Disease-10 code for billing without ordering of the treatments above. Chi-square tests (Table 2) indicated that the proportion of patients receiving referrals to the Health and Wellness Center (a weight loss clinic) was lower in the intervention phase compared with usual care, χ2(1) = 8.38, P = 0.004, 95% CI (5.9%, 4.9%) as was the proportion of patients who received bariatric surgery, χ2(1) = 7.22, P = .007, 95% CI (0.6%, 0.08%). In contrast, the proportion of patients reporting use of anti-obesity medications, χ2(1) = 107.77, P < 0.001, 95% CI (6.5%, 4.4%), was higher in the intervention phase than in usual care. No other significant differences in the proportions of patients receiving the remaining referrals were observed between the intervention and usual care phases.

Engagement of the clinics with the implementation strategies

A crude estimate of clinic engagement was quantified using an engagement score (0–8; low to high engagement) and was based on the clinics’ and/or at least one clinician per clinic documented participation in up to 8 implementation activities (participation in each activity by the 56 clinics is shown in parentheses): (1) virtual introductory meeting (55/56), (2) in-person all-clinic training (49/56), (3) individual consultation (29/56), (4) obesity e-learning module (35/56), (5) World Obesity Federation SCOPE training (17/56), (6) posted signage informing patients that weight-prioritized visits were available (18/56), (7) attending a learning community meeting (14/56) and/or (8) identifying a champion for PATHWEIGH (18/56). A total of 36 clinics (64%) showed moderate engagement (score 3–5), 12 clinics (21%) engaged to a greater degree (score 6–8) and 8 clinics (14%) engaged to a lesser degree (score 0–2; Fig. 3).

Safety

No health metric (Table 1) changed ≥1% in an unfavorable direction in the intervention. Death rates were very low in our patient population, 0.6% during usual care and 1.7% during the intervention (each over 3 years). The higher death rate during the intervention is probably due to the enrichment of patients seen in both phases who were older in the intervention versus usual care (>50% of our population; Table 1). Due to the timing of the trial (data capture began in March 2020; the first intervention group started in March 2021), COVID-related deaths became much less common as more patients were being exposed to the intervention.

Discussion

The steady rise in the prevalence of obesity has been attributed to an average population weight gain of only 0.5 kg yr−1 (refs. 9,10). Hence, there is reason to believe that preventing population weight gain by 0.5 kg yr−1 may be sufficient to curtail the surging epidemic of obesity. Major findings from our study provide an example of how this may be accomplished. The composite PATHWEIGH intervention mitigated population weight gain by 0.58 kg over 18 months and changed the trajectory from weight gain to weight loss. This result should not be misinterpreted to mean that 0.58 kg is clinically meaningful to a singular patient; rather, it is urged to look beyond to its potential impact on public health. Although only 25% of adults with a BMI ≥ 25 kg m2 received discernable care for their weight at any time during our 4-year data collection period, PATHWEIGH increased the likelihood of a patient receiving weight-related care by 23% during the intervention. Furthermore, when patients did receive discernable weight-related care, PATHWEIGH was associated with greater weight loss and also mitigated the expected weight gain for those who did not receive discernable weight-related care. These data show positive patient weight-related outcomes across an entire health system’s adult-serving primary care clinics and serve as an example of a pragmatic, scalable approach to obesity that can curb population weight gain and improve obesity care for individual patients.

Recent years have ushered in numerous and diverse evidence-based options for weight management. Nevertheless, research evidence is notoriously slow to reach clinical practice11,12 and the medical establishment has been reluctant to adopt the treatment of obesity, in particular. Interventions tested in primary care, specifically, have shown successful patient weight loss under conditions in which patients have been recruited into a weight loss intervention with a set curriculum and coaches13,14,15,16, neither of which are reminiscent of routine practice. By randomizing on the clinic (versus patient) level, as was done in previous trials, only 6.3% of our patients were exposed to the types of interventions tested in highly controlled trials; hence, the results cannot be directly compared. The current pragmatic clinical trial provides externally valid evidence17,18 that subtle changes to the core medical care process can favorably impact the population weight trajectory in a way that may be more sustainable. PATHWEIGH was successfully implemented and mitigated patient weight gain across a health system’s adult-serving primary care network up to 18 months, despite the fact that most adults with a BMI ≥ 25 kg m2 did not receive discernable care for their weight.

Of the eligible patients, 25% received some discernable care for their weight at least once during the trial. Most care remained limited, presumably, to advice for lifestyle modification (not captured in this trial) as referrals, prescribing of anti-obesity medication and bariatric surgery were relatively uncommon. Nevertheless, unlike previous trials testing the impact of lifestyle modification on weight loss, weight did not reach a nadir 6–12 months into the intervention19,20, but continued to decline through 18 months. The large relative increase in the prescribing of anti-obesity medications (8.7–14.8%) may have contributed to the accentuated weight loss in the intervention for those being treated and also indicated an inflection point in clinician willingness to treat obesity as a chronic disease. Most noteworthy is that PATHWEIGH was associated with an increase in the likelihood of patients receiving weight-related care by 23%. Hence, there is reason to believe that simply having a care process to meet the demand for weight management assistance in a medical setting can increase the number of patients receiving help.

Motivating change in medical practice is notoriously challenging21,22. Considerable literature cites the misalignment of the widespread use of extrinsic motivators (that is financial incentives or disincentives) in physicians who are inherently intrinsically motivated by improved competency and better patient outcomes23,24. Indeed, clinician education on best practices for obesity management and training on the use of PATHWEIGH as a care process resulted in the greatest engagement with the clinics. Hence, it is likely that greater awareness and education around obesity as a disease led to more robust lifestyle advice that was not captured in our study but was captured inadvertently by our data showing less weight gain during the intervention versus usual care in patients identified as never having received weight-related care.

Results from this pragmatic trial should be interpreted in light of its limitations. The use of real-world data with measurement of weights available from sporadic clinic visits required the use of models to examine weight trajectories, and potential model misspecifications may have impacted the results. A sensitivity analysis comparing the 3-piecewise linear model (presented herein) to more flexible models using 8 or 19 pieces is provided in Extended Data Table 6. Goodness of fit of the 3-piecewise linear model for observed versus residual or fitted values overall and by subgroups are shown in Extended Data Figs. 1–3 and Extended Data Table 6. The 3-piece model was retained for parsimony and ease of interpretation. The generalizability of the results is limited to patients with two or more measured weights who tended to be older, were women, have a higher BMI and were insured by Medicare compared with those with fewer than two weights. While the stepped-wedge design resulted in random interruption in patients’ weight trajectories, the timing of changes in unmeasured factors, such as the COVID-19 public health emergency, may have disproportionately impacted the usual care and intervention phases of the study. Weight was recorded by self-report for telehealth visits during the COVID-19 lockdown from March to June 2020 and was notoriously underreported. Evidence suggests that population weight gain was comparable during versus before the pandemic25; however, speculation exists that the disproportionate mortality rate from COVID-19 in people with obesity is responsible for the small decrease in the prevalence in obesity in the USA from 2017–2020 to 2021–202326,27 masking continued trends in population weight gain. Similarly, secular trends in the popularity and availability of anti-obesity medications may have disproportionately impacted the usual care and intervention phases. A sensitivity analysis adjusting for whether the patient was prescribed any anti-obesity medication or was first weighed early in the trial (during COVID-19) did not change the results. Anti-obesity medication use mediated only 4% of the weight loss. Finally, the pragmatic implementation of PATHWEIGH precluded the random assignment of patients to receive discernable care for their weight, limiting the analysis to measuring associations rather than causal relationships for this key element of delivering weight management in primary care settings.

In conclusion, PATHWEIGH was successfully implemented across 56 clinics in the state of Colorado and mitigated population weight gain across a health system’s entire adult-serving primary care network up to 18 months. PATHWEIGH increased the likelihood of patients receiving care for their weight and was associated with greater weight loss when they received care. The results show how conventional workflows and existing resources can be optimized to improve patient outcomes at scale.

Methods

Trial design

An effectiveness-implementation hybrid type 1 stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized pragmatic trial28 was conducted in 56 primary care clinics in a single health care system in Colorado, USA (Extended Data Table 1). Randomization was performed at the clinic level, and the stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized pragmatic design was chosen to facilitate implementation of the intervention at all participating sites (Fig. 1).

Clinics were randomized into three clusters using computer-generated covariate-constrained randomization balanced for patient volume, percentage of patients on Medicaid, academic versus nonacademic, practice type (family medicine, internal medicine or both) and geographical location of the clinic (rural versus urban or suburban)29. Initially, 57 clinics were randomized; however, one clinic was identified after randomization to not be primary care. Hence, it was not engaged and was excluded thereafter. Baseline patient characteristics were comparable between the clusters4. All clinics were unaware of their randomized sequence assignment until 3 months before the implementation of the intervention; at that point, staff were informed about the intervention and the implementation team performed training before crossover. A usual care control period (17 March 2020 to 16 March 2021) preceded sequential intervention rollout: March 2021 for cluster 1, March 2022 for cluster 2 and March 2023 for cluster 3. Clusters remained in the usual care condition until they received the intervention, and clusters remained in the intervention once they received it (one-way crossover). Rollout was timed via the EHR to ensure cluster-level fidelity and minimize contamination.

Trial population

The ITT population under study was composed of adults (≥ 18 years) having a BMI ≥ 25 kg m2 and were seen and weighed in one of the clinics by a primary care clinician with a national provider identifier between 17 March 2020 and 16 March 2024. Both men and women were included and sex was determined by self-report. A prespecified secondary analysis was also performed for patients who received discernable medical attention for their weight, >98% of whom were identified by clinician use of a weight-related International Classification of Disease-10-CM code for billing (E66-E.66.9, Z68.25-45). It was unknown whether patients had received care before 17 March 2020. BMI values were excluded if they were suspected to be erroneous (height < 135 cm and >225 cm; weight > 273 kg).

Trained personnel who were unaware of the clinic sequence assignments extracted prespecified clinical information from the EHR for patients seen in the 56 clinics. Patients were assigned unique encoded identifiers and all data were de-identified. We implemented a custom data processing and analysis pipeline for longitudinal EHR data to characterize patient weight trajectories for evaluating weight-related clinical outcomes. Because all data were de-identified, the study was exempt from informed consent and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, including a waiver of informed consent, and the full protocol has been published29. No patient was ‘recruited’ or experienced their care as part of research.

Trial intervention

The trial intervention included a bundle of three components.

-

(1)

Health system primary care leadership endorsement. Implementation began with health system leadership emailing regional clinic managers to engage with the PATHWEIGH research team, which proved critical to initiating the care process. They ensured fidelity with the intervention by refraining from introducing other weight loss approaches that could impact our results during the trial and also by continuing to support the process after the funding period.

-

(2)

Implementation strategies. The clinics engaged with the research team through their participation in activities designed to support use of the care process as well as educate clinicians on obesity treatment. The following were the implementation strategies: (1) a virtual introductory meeting between the research team and each individual clinic, (2) in-person all-clinic training conducted by a research team clinician, (3) opportunity for consultation between primary care clinicians or staff with appropriate members of the research team, (4) access to an on-demand obesity e-learning module, (5) access to extended World Obesity Federation training, (6) signage informing patients that weight-prioritized visits were available, (7) monthly virtual learning community meetings covering a broad range of topics and (8) encouragement that each clinic identify a champion for PATHWEIGH.

-

(3)

Customization of the EHR. Customization of the EHR was one component of PATHWEIGH and included three sequential steps for patients, clinic staff and clinicians. Signage was mailed with instructions that it should be posted in the clinics, encouraging patients to schedule a ‘weight-prioritized visit’ (WPV; a new visit type in the EHR) with their clinician if they would like medical assistance with their weight (step 1). Scheduling the WPV prompted the EHR to send a weight management questionnaire through the patient portal (which is used by 85% of patients in the health system) 72 h before the visit, with a request that they complete it before their visit (step 2). Clinicians were trained to import the patient weight management questionnaire into their clinic notes and use the patients’ answers to direct the conversation and inform the treatment plan. Note-embedded support tools and weight management order sets were designed to reduce cognitive load and improve both chart navigation and documentation efficiency by consolidating any potential aspect of treatment into a single interface (that is referrals or prescription of anti-obesity medication; step 3). Prompts for optimal billing, follow-up and links to patient handouts were included. Use of the care process was entirely voluntary and may have entailed using 1, 2 or all 3 steps. Enduring onboarding materials were developed to introduce and sustain the intervention in the case of provider and/or staff turnover.

Trial outcomes

Two coprimary outcomes were specified: (1) change in patient weight trajectories over the 6 months after the initial weight measured in the usual care and intervention phases and (2) change in patient weight maintenance, as measured by patient weight trajectories from 6 months to 18 months after the initial weight measurement, in the usual care and intervention phases.

Statistical analyses

Data were collected from patients whose initial visit with a recorded weight occurred between 17 March 2020 and 17 March 2024, with censoring on the final day of follow-up, 17 September 2024. The primary analysis followed an ITT strategy in which weight trajectories of our patient population were examined over the usual care and intervention phases, regardless of whether patients received discernable care for their weight, using an interrupted time series framework. Due to the real-world nature of this study, weight trajectories were modeled using all observed weights from a patient’s first recorded weight to the end of the follow-up period, including patients with weights measured in both phases and patients with weights measured only in the usual care or intervention phase. In addition, a prespecified secondary analysis examined weight trajectories for patients after they were first identified as receiving discernable care for their weight in the usual care and/or intervention phases. For the ITT, counterfactual analyses were used to compare model-predicted average weight measurements at 6 months and weight maintenance between 6 months and 18 months after the index weight in the usual care and intervention phases. For the prespecified secondary analyses, we compared weight measurements at 6 months and weight maintenance between 6 months and 18 months, distinguishing among patients who received versus did not receive discernable care for their weight across the usual care and intervention phases. Average weight loss at 6 months and weight maintenance at 18 months were calculated using model predictions.

Linear mixed models were used to analyze patient weight trajectories from the index weight to all other weight measures in the usual care and intervention phases. Weight trajectories were modeled as a continuous piecewise linear function with different slopes from 0 month to 6 months and 6 months to 18 months for each phase. A continuous piecewise linear function was also used to model weight trajectories in the intervention phase with different slopes from 0 month to 6 months and 6 months to 18 months. Patients were considered in the intervention phase at the time of their first visit with a measured weight in a clinic that had transitioned to the intervention. In the prespecified secondary analyses, additional continuous piecewise linear functions were used to model weight trajectories following the first visit in which they received discernable care for their weight in each phase, with different slopes from 0 month to 6 months and 6 months to 18 months after their weight-related visit. Results were confirmed robust by comparing the piecewise linear model to a nonlinear quadratic model. Counterfactual analyses compared weight trajectories in five scenarios; hence, a P value threshold of 0.01 was used to account for Bonferroni adjustments. GEE logistic models were used to examine the proportion of patients who received discernable care for their weight in the usual care and/or intervention phases, accounting for multiple patient-level observations.

The linear mixed models adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, and calendar year of the index visit. Random intercepts were assumed for repeated measures from the same patients, and another random intercept was shared by visits to the same clinic. The GEE logistic models adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, calendar year of the index visit, weight measured at the initial visit and the randomly assigned cluster of the clinic where a patient’s initial visit occurred. Robust sandwich variance estimators were used. Data were collected using R v.4.4.1. Data analysis used R ImerTest 3.1-3 for the main modeling and Ime 4 1.1-35.5 for contrasts and confidence intervals.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Due to the very large data set (1.6 million data rows in >250,000 patients) and complex nature of the data, the data have not been placed in a public repository. De-identified data may be shared upon request. The protocol has been previously published29.

References

Global Burden of Disease Collaborators Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: a forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 405, 813–838 (2025).

Kyle, T. K. & Stanford, F. C. Moving toward health policy that respects both science and people living with obesity. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 56, 635–645 (2021).

Pantalone, K. M. et al. Prevalence and recognition of obesity and its associated comorbidities: cross-sectional analysis of electronic health record data from a large US integrated health system. BMJ Open 7, e017583 (2017).

Perreault, L. et al. Baseline characteristics of PATHWEIGH: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized study for weight management in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 21, 249–255 (2023).

Kushner, R. F. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev. Med. 24, 546–552 (1995).

Wadden, T. A. et al. Managing obesity in primary care practice: an overview with perspective from the POWER-UP study. Int. J. Obes. 37, S3–S11 (2013).

Kaplan, L. M. et al. Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity care: results from the national ACTION study. Obesity 26, 61–69 (2018).

Stoops, H. & Dar, M. Equity and obesity treatment—expanding Medicaid-covered interventions. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 2309–2311 (2023).

Mozaffarian, D., Hao, T., Rimm, E. B., Willett, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2392–2404 (2011).

Wing, R. R. et al. Weight gain over 6 years in young adults: the study of novel approaches to weight gain prevention randomized trial. Obesity 28, 80–88 (2020).

Green, L. W., Ottoson, J. M., Garcia, C. & Hiatt, R. A. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 30, 151–174 (2009).

Westfall, J. M., Mold, J. & Fagnan, L. Practice-based research—“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA 297, 403–406 (2007).

Appel, L. J. et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1959–1968 (2011).

Katzmarzyk, P. T. et al. Weight loss in underserved patients—a cluster-randomized trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 909–918 (2020).

Wadden, T. A. et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2111–2120 (2005).

Wadden, T. A. et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1969–1979 (2011).

Ford, I. & Norrie, J. Pragmatic trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 454–463 (2016).

Loudon, K. et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. Brit. Med. J. 350, h2147 (2015).

Knowler, W. C. et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403 (2002).

Look Ahead et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 145–154 (2013).

Etchegary, C., Taylor, L., Mahoney, K., Parfrey, O. & Hall, A. Changing health-related behaviours 5: on interventions to change physician behaviours. Methods Mol. Biol. 2249, 613–630 (2021).

Saddawi-Konefka, D., Schumacher, D. J., Baker, K. H., Charnin, J. E. & Gollwitzer, P. M. Changing physician behavior with implementation intentions: closing the gap between intentions and actions. Acad. Med. 91, 1211–1216 (2016).

Herzer, K. R. & Pronovost, P. J. Physician motivation: listening to what pay-for-performance programs and quality improvement collaboratives are telling us. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 41, 522–528 (2015).

Madara, J. L. & Burkhart, J. Professionalism, self-regulation, and motivation: how did health care get this so wrong?. JAMA 313, 1793–1794 (2015).

Wing, R. R., Venkatakrishnan, K., Panza, E., Marroquin, O. C. & Kip, K. E. Association of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders with 1-year weight changes. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2217313 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and severe obesity prevalence in adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. CDC https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db508.htm (2023).

Restrepo, B. J. Obesity prevalence among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Prev. Med. 63, 102–106 (2022).

Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M. & Stetler, C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care 50, 217–226 (2012).

Suresh, K. et al. PATHWEIGH, pragmatic weight management in adult patients in primary care in Colorado, USA: study protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. Trials 23, 26 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank the UCHealth leadership team, the Health Data Compass Data Warehouse project (https://www.healthdatacompass.org) and the internal Epic personnel at UCHealth and the University of Colorado School of Medicine, as well as the clinics, staff, providers and patients that made this trial successful. This study was inspired by G. Bray and D. Ryan. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (1R18DK127003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P. and J.S.H. conceived the study, obtained funding and engaged the investigative team. Implementation was done by L.P., E.S.K., P.C.S. and L.T. Quantitative analysis was done by C.R., Q.P. and R.M.G. Qualitative work and analysis were done by J.S.H., C.T., L.C. and J.W. C.R. directly accessed and verified the data. All authors had full access to the data and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.P. has received personal fees for consulting and/or speaking from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim and Ascendis. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Nerys Astbury, Ying Wei and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ashley Castellanos-Jankiewicz, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Goodness-of-fit (residual vs. fitted values) overall for the 3-piece model.

Participant flow (CONSORT diagram) and study design; hatched bars indicate the control phase and solid bars indicate the intervention phase.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Goodness-of-fit (residual vs. fitted values) for observed vs. predicted values for the full sample.

Predicted weight trajectories for eligible patients with a measured weight A) in the usual care (blue line) and intervention (red line) phases from 0–6 months and 6–18 months from their first weight regardless of whether they received discernable weight-related care in the ITT sample, and B) who received weight-related care in the usual care (blue line) or intervention phase (pink line), and those who never received weight-related care in the usual care (purple line) or intervention phase (green line) in the pre-specified secondary analysis. The two-piece (0–6 months and 6–18 months) solid lines are predicted weights for a hypothetical average patient during follow-up with 95% prediction intervals in gray.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Goodness-of-fit (residual vs. fitted values) for observed vs predicted values in the subgroups of eligible patients who did not (0) vs. did (1) receive weight-related care, respectively.

Percentage of the 56 clinics that participated in each implementation activity. WOF = World Obesity Federation SCOPE training.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perreault, L., Pan, Q., Rodriguez, C. et al. Implementation and effectiveness of a care process to prioritize weight management in primary care: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial. Nat Med (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04051-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04051-5