Abstract

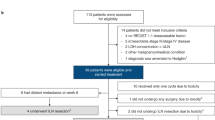

Neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab has become standard therapy for stage III melanoma based on the NADINA trial, although long-term data are lacking. In the phase 2 PRADO cohort of OpACIN-neo, 99 patients with stage III macroscopic melanoma received this regimen. Here we report first-time 5-year survival data: 71% event-free survival, 74% relapse-free survival, 79% distant metastasis-free survival and 86% overall survival. Ongoing grade 1−2 immune-related adverse events occurred in 69% of patients alive, predominantly vitiligo and hypothyroidism. Major pathologic response (MPR), high tumor mutational burden (TMB), high interferon-gamma (IFNγ) signature and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher were associated with favorable outcomes. Combined high TMB, IFNγ and PD-L1 expression yielded 100% MPR and 100% 5-year event-free survival, whereas triple low expression had only 18% MPR and 41% event-free survival. Our findings demonstrate favorable long-term outcomes for patients with an MPR and identify IFNγ and PD-L1 as promising baseline biomarkers. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02977052.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

RNA sequencing and DNA sequencing data generated during the study will be deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) for PRADO under accession codes EGAS50000000268 (DNA) or EGAS00001007601 (RNA) and for OpACIN-neo under accession codes EGAS00001004832 (DNA) or EGAS00001004833 (RNA). To minimize the risk of patient re-identification, de-identified individual patient-level clinical data are available under restricted access. Upon scientifically sound request, data access can be obtained via the Netherlands Cancer Institute’s scientific repository at repository@nki.nl, which will contact the corresponding author (C.U.B.). Data requests will be reviewed by the institutional review board of the Netherlands Cancer Institute and will require the requesting researcher to sign a data access agreement with the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Code availability

All codes were written in R (versions 4.3.0 and 4.2.2) and Python (version 3.12.5). The code is available via GitHub at https://github.com/BlankLab-NKI/PRADO_TR.

References

Blank, C. U. et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab and ipilimumab in resectable stage III melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1696–1708 (2024).

Patel, S. P. et al. Neoadjuvant-adjuvant or adjuvant-only pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 813–823 (2023).

Forde, P. M. et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1976–1986 (2018).

Vos, J. L. et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab induces major pathological responses in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 12, 7348 (2021).

Chalabi, M. et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient early-stage colon cancers. Nat. Med. 26, 566–576 (2020).

van Dijk, N. et al. Preoperative ipilimumab plus nivolumab in locoregionally advanced urothelial cancer: the NABUCCO trial. Nat. Med. 26, 1839–1844 (2020).

Cascone, T. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in operable non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 platform NEOSTAR trial. Nat. Med. 29, 593–604 (2023).

Schmid, P. et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 810–821 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Improved efficacy of neoadjuvant compared to adjuvant immunotherapy to eradicate metastatic disease. Cancer Discov. 6, 1382–1399 (2016).

Blank, C. U. et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat. Med. 24, 1655–1661 (2018).

Huang, A. C. et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat. Med. 25, 454–461 (2019).

Amaria, R. N. et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in high-risk resectable melanoma. Nat. Med. 24, 1649–1654 (2018).

Rozeman, E. A. et al. Identification of the optimal combination dosing schedule of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN-neo): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 20, 948–960 (2019).

Lucas, M. W. et al. LBA42 Distant metastasis-free survival of neoadjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus adjuvant nivolumab in resectable, macroscopic stage III melanoma: the NADINA trial. Ann. Oncol. 35, S1233–S1234 (2024).

Cristescu, R. et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 362, eaar3593 (2018).

Rozeman, E. A. et al. Survival and biomarker analyses from the OpACIN-neo and OpACIN neoadjuvant immunotherapy trials in stage III melanoma. Nat. Med. 27, 256–263 (2021).

Menzies, A. M. et al. Pathological response and survival with neoadjuvant therapy in melanoma: a pooled analysis from the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium (INMC). Nat. Med. 37, 9503 (2019).

Reijers, I. L. M. et al. Impact of personalized response-directed surgery and adjuvant therapy on survival after neoadjuvant immunotherapy in stage III melanoma: comparison of 3-year data from PRADO and OpACIN-neo. Eur. J. Cancer 214, 115141 (2025).

Versluis, J. M. et al. Survival update of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma in the OpACIN and OpACIN-neo trials. Ann. Oncol. 34, 420–430 (2023).

Reijers, I. L. M. et al. Representativeness of the index lymph node for total nodal basin in pathologic response assessment after neoadjuvant checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with stage III melanoma. JAMA Surg. 157, 335–342 (2022).

Schermers, B. et al. Surgical removal of the index node marked using magnetic seed localization to assess response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with stage III melanoma. Br. J. Surg. 106, 519–522 (2019).

Reijers, I. L. M. et al. Personalized response-directed surgery and adjuvant therapy after neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab in high-risk stage III melanoma: the PRADO trial. Nat. Med. 28, 1178–1188 (2022).

Long, G. V. et al. LBA41 long-term survival with neoadjuvant therapy in melanoma: updated pooled analysis from the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium (INMC). Ann. Oncol. 35, S1232 (2024).

Tetzlaff, M. T. et al. Pathological assessment of resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy for metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 29, 1861–1868 (2018).

Larkin, J. et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III/IV melanoma: 5-year efficacy and biomarker results from CheckMate 238. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 3352–3361 (2023).

Patel, S. P. et al. 1601O 3-year survival with neoadjuvant-adjuvant pembrolizumab from SWOG S1801. Ann. Oncol. 36, S946–S947 (2025).

Menzies, A. M. et al. Pathological response and survival with neoadjuvant therapy in melanoma: a pooled analysis from the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium (INMC). Nat. Med. 27, 301–309 (2021).

Wolchok, J. D. et al. Final, 10-year outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 11–22 (2025).

Ascierto, P. A. et al. Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg versus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 611–622 (2017).

Angka, L. et al. Natural killer cell IFNγ secretion is profoundly suppressed following colorectal cancer surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25, 3747–3754 (2018).

Leaver, H. A., Craig, S. R., Yap, P. L. & Walker, W. S. Lymphocyte responses following open and minimally invasive thoracic surgery. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 30, 230–238 (2000).

van Not, O. J. et al. Association of immune-related adverse event management with survival in patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1794–1801 (2022).

Verheijden, R. J. et al. Corticosteroids for immune-related adverse events and checkpoint inhibitor efficacy: analysis of six clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 3713–3724 (2024).

Verheijden, R. J. et al. Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants for immune-related adverse events and checkpoint inhibitor effectiveness in melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 207, 114172 (2024).

Reijers, I. L. M. et al. IFN-γ signature enables selection of neoadjuvant treatment in patients with stage III melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 220, e20221952 (2023).

Ayers, M. et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 2930–2940 (2017).

Jiang, H., Lei, R., Ding, S. W. & Zhu, S. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 182 (2014).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Putri, G. H., Anders, S., Pyl, P. T., Pimanda, J. E. & Zanini, F. Analysing high-throughput sequencing data in Python with HTSeq 2.0. Bioinformatics 38, 2943–2945 (2022).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Hanssen, F. et al. Scalable and efficient DNA sequencing analysis on different compute infrastructures aiding variant discovery. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 6, lqae031 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in these trials. We gratefully acknowledge the support of all colleagues from Melanoma Institute Australia, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Royal North Shore and Mater Hospitals, University Medical Center Utrecht, Erasmus Medical Center, Leiden University Medical Center, University Medical Center Groningen and the Netherlands Cancer Institute. We also thank B. Schermers from Sirius Medical for providing magnetic seeds and a magnetic seed detector; S. Vanhoutvin for financial management; M. J. Gregorio, K. de Joode, A. M. van Eggermond, E. H. J. Tonk and J. Kingma-Veenstra for administrative support and data management; and A. Evans and B. Stegenga from Bristol Myers Squibb for scientific input and long-term support of our neoadjuvant immunotherapy efforts. A.M.M. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHRMC) Investigator Grant. R.P.M.S. is supported by Melanoma Institute Australia. R.A.S. is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (2022/GNT2018514). G.V.L. is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant and the University of Sydney Medical Foundation. Financial support for the study was provided by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.U.B. designed the trial and wrote the protocol. The final amendment of the PRADO extension was written by E.A.R. together with C.U.B. in the 20th Workshop on ‘Methods in Clinical Cancer Research’ (Zeist, The Netherlands). A.C.J.v.A. and G.V.L. reviewed and gave input to the trial protocol. I.L.M.R., A.M.M., R.P.M.S., J.M.V., W.J.v.H., E.A.R., E.K., A.A.M.v.d.V., K.P.M.S., H.E., G.A.P.H., J.A.v.d.H., D.J.G., A.J.W., J.M.L., W.M.C.K., C.L.Z., A. Bruining, A.A.M., T.E.P., K.F.S., S. Chʼng, A.J.S., J.B.A.G.H., A.C.J.v.A., G.V.L. and C.U.B. included and treated patients and collected clinical data. A.T.A., L.G.G.-O. and A.v.d.W. contributed to central and local data management. M.G. was a clinical project manager of the trial. S. Cornelissen performed DNA and RNA isolations. A. Broeks coordinated and contributed to translational laboratory logistics and immunohistochemistry and molecular laboratory work. P.D. and J.R. performed the bioinformatics analysis. A.J.C., R.V.R., R.A.S. and B.A.v.d.W. reviewed and scored the pathology of all cases. L.L.H. and M.L.-Y. performed the statistical analyses. L.L.H. and C.U.B. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors interpreted the data, reviewed the paper and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No author has received financial support for the work on this paper, and no medical writer was involved at any stage of the preparation of this paper. A.M.M. has served on advisory boards for Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche, Pierre Fabre and QBiotics. R.P.M.S. has received honoraria for advisory board participation from Merck Sharp & Dohme and Clinical Laboratories Pty Ltd. W.J.v.H. has received speakerʼs honoraria from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Belpharma and Novartis; reports an advisory role with Belpharma; and has received a research grant from Amgen. E.K. has consultancy/advisory relationships with Delcath, Immunocore and Lilly and has received research grants unrelated to this paper from Bristol Myers Squibb, Delcath, Novartis and Pierre Fabre. These grants are unrelated to the present work and are paid to the institution. A.A.M.v.d.V. received travel fees from Ipsen and consultancy fees (all paid to the institution) from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ipsen, Eisai, Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche and Pierre Fabre. K.P.M.S. has consultancy/advisory relationships with AbbVie and Sairopa; has received research funding from TigaTx, Bristol Myers Squibb, Philips, Genmab and Pierre Fabre; and has received honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb (all paid to the institution). H.E. has received institutional research grants from SkyLineDx, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis and Pierre Fabre; a speaker honorarium from Janssen; and non-personal speaker honoraria (paid to the hospital) from Bristol Myers Squibb and Novartis. H.E. has also served on expert boards for Pierre Fabre and Bristol Myers Squibb. G.A.P.H. reports consultancy/advisory relationships with Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Sanofi and Pierre Fabre and receiving research grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Seerave (all paid to the institution). S. Ch’ng receives fees for professional services provided to Merck Sharp & Dohme and SkylineDx. J.B.A.G.H. reports advisory roles for Achilles Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Immunocore, Instil Bio, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Ipsen, Molecular Partners, MSD Oncology, Neogene Therapeutics, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Sāstra, Third Rock Ventures and T-Knife; has received research funding (paid to the institution) from Amgen, Asher Biotherapeutics, BioNTech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Neon Therapeutics and Novartis; and is a stockowner of Neogene Therapeutics and Sāstra. R.V.R. has received honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme. R.A.S. has received fees for professional services from SkylineDx, IO Biotech ApS, MetaOptima Technology, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Evaxion, Provectus Biopharmaceuticals Australia, QBiotics, Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dohme, NeraCare, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Myriad Genetics and GlaxoSmithKline. A.C.J.v.A. reports advisory roles with Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Genmab, Menarini Silicon Biosystems, Merck Serono-Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Neracare, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Replimune, Sanofi, Sirius Medical, SkylineDx and 4SC and has received research funding from Amgen, Merck Serono-Pfizer and SkylineDx. G.V.L. is a consultant advisor for Agenus, Amgen, Array Biopharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, BioNTech, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Bristol Myers Squibb, Evaxion Biotech A/S, Fortiva Biologics, GI Innovation, Hexal AG (a Sandoz company), Highlight Therapeutics, IO Biotech, Immunocore Ireland Limited, Innovent Biologics, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis Pharma AG, OncoSec Medical Australia, PHMR Limited, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Scancell Limited and SkylineDX. C.U.B. reports that he has received compensation for advisory roles from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Lilly, GenMab, Pierre Fabre, Third Rock Ventures and Senya; has received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, NanoString and 4SC; and is co-founder of Immagene. All compensations and funding for C.U.B. were paid to the institution, except for Third Rock Ventures and Immagene. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Ahmad Tarhini and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ulrike Harjes, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Five-year survival analysis for the whole patient cohort and according to pathologic response subgroup for the confirmation-cohort OpACIN-neo.

a-e, Kaplan Meier curve of all patients, including the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for event free survival (n = 86) (a), relapse-free survival (n = 83) (b), distant metastases-free survival (n = 83) (c), overall survival (n = 86) (d), melanoma specific survival (from registration to melanoma related death) (n = 83) (e). f-h, Kaplan Meier curves including log-rank P value, sub grouped according to pathologic response (major pathologic response, MPR), pathologic partial response, pPR; pathologic non-response, pNR) of relapse-free survival (n = 83) (f), distant metastases-free survival (n = 83) (g), and melanoma specific survival (from surgery to melanoma related death) (n = 80) (h).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Five-year survival analysis per treatment arm for the confirmation-cohort OpACIN-neo.

Patients in the OpACIN-neo trial were randomized to receive 2 cycles op ipilimumab (IPI) 3 mg kg−1 plus nivolumab (NIVO) 1 mg kg−1 in arm A (n = 30), 2 cycles of IPI 1 mg kg−1 plus NIVO 3 mg kg−1 in arm B (n = 30), or 2 cycles op IPI 3 mg kg−1 followed by NIVO 3 mg kg−1 in arm C (n = 26). a-e, Kaplan Meier curve including log-rank P value, sub grouped according to treatment-arm, for event free survival (a), relapse-free survival (b), distant metastases-free survival (c), overall survival (d), melanoma specific survival (from registration to melanoma related death) (e).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Forest Plot of Hazard Ratios for distant metastasis free survival by baseline variables.

Forest plot of risk for distant metastasis calculated from surgery (n = 92) using univariable Cox-regression analysis expressed in hazard-ratios per variable (square), with a 95% confidence interval (horizontal line) and P value compared to the reference variable. * Time-dependent variable. EU, Europe; AUS, Australia; LN, lymph node; MPR, major pathologic response; pPR, pathologic partial response; pNR, pathologic non-response; irAE, immune related adverse events; IFNγ, interferon gamma gene signature; TMB, tumor mutational burden; PD-L1, Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1; CI, confidence interval.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Forest Plots of Hazard Ratios for relapse free (a) and overall survival (b) by baseline variables.

a, Forest plot of risk for recurrence, calculated from surgery (n = 92). b, Forest plot of risk for death, calculated from registration (n = 99); by using univariable Cox-regression analysis expressed in hazard-ratios per variable (square), with a 95% confidence interval (horizontal line) and P value compared to the reference variable. * Time-dependent variable. EU, Europe; AUS, Australia; LN, lymph node; MPR, major pathologic response; pPR, pathologic partial response; pNR, pathologic non-response; irAE, immune related adverse events; IFNγ, interferon gamma gene signature; TMB, tumor mutational burden; PD-L1, Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Five-year survival analysis of patients with or without BRAF mutation for the confirmation-cohort OpACIN-neo.

a-e, Kaplan Meier curves, including log-rank P value, sub grouped according to presence / absence of BRAF-V600E/K mutation for event free survival BRAF-mutant (n = 37) versus BRAF-wildtype (n = 36) (a), relapse-free survival in BRAF-mutant (n = 35) versus BRAF-wildtype (n = 35) (b), distant metastases-free survival in BRAF-mutant (n = 35) versus BRAF-wildtype (n = 35) (c), overall survival in BRAF-mutant (n = 37) versus BRAF-wildtype (n = 36) (d), and melanoma specific survival in BRAF-mutant (n = 36) versus BRAF-wildtype (n = 34) (from registration to melanoma related death) (e). f,g, Kaplan Meier curves including log-rank P value, per based on their BRAF mutational status and treatment-arm (arm A (ipilimumab 3 mg kg−1 plus nivolumab 1 mg kg−1) versus arm B (ipilimumab 1 mg kg−1 plus nivolumab 3 mg kg−1)): BRAF-mutant patients treated in arm A (n = 13), BRAF-mutant treated in arm B (n = 12), BRAF-wildtype treated in arm A (n = 13) and BRAF-wildtype treated in arm B (n = 14), for event free survival (f) and overall survival (g).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Outcome according to single baseline biomarkers for the conformation-cohort OpACIN-neo.

a-e, Kaplan Meier curves of event-free survival and overall survival curve including log-rank P value, according to baseline based IFNγ score high (n = 18) vs low (n = 34) (a,b), according to baseline TMB high (n = 28) vs low (n = 35) (c,d), and according to baseline PD-L1 expression, TPS score <1% (n = 41) vs TPS score ≥1% (n = 26) (e,f). g-i, ROC curves for IFNγ (AUC = 0.685) (g), TMB (AUC = 0.666) (h), and PD-L1 (AUC = 0.482) (i). ROC curve analyses used a binary outcome (event within five years), since follow-up among all event-free patients was ≥58 months for all but one patient.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Outcome according to triple combination of baseline biomarkers for the conformation-cohort OpACIN-neo.

a, Bar plot showing the percentage of patients achieving MPR (including 95% confidence interval) sub grouped according to the combination of the three biomarkers: low TMB, low IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 11); low TMB, low IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 4); high TMB, low IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 8); low TMB, high IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 4); high TMB, high IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 4); low TMB, high IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 4); high TMB, low IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 6); high TMB, high IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 3). b, Kaplan Meier curve, including log-rank P value for event free survival, according to the three biomarker subgroups as described in a. c, ROC curves for low TMB, low IFNγ and low PD-L1 versus other biomarker combinations (AUC = 0.701) and for high TMB, high IFNγ and high PD-L1 versus the other biomarker combinations (AUC = 0.776). ROC curve analyses used a binary outcome (event within five years), since follow-up among all event-free patients was ≥58. d,e, Kaplan Meier curves, including log-rank P value for event free survival of patients with low IFNγ, low TMB and low PD-L1 (n = 11) versus all other biomarker combinations (n = 33) (d), and of patients with high IFNγ, high TMB and high PD-L1 (n = 3) versus all other biomarker combinations (n = 41) (e).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Outcome according to baseline IFNγ and PD-L1 for the conformation-cohort OpACIN-neo.

a, Bar plot showing percentage of patients achieving MPR (including 95% confidence interval) according to baseline IFNγ and PD-L1: low IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 19); low IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 11); high IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 8); high IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 7). b, Kaplan−Meier curves, including log-rank P value for EFS, showing EFS according to IFNγ and PD-L1 subgroups as described at a. c,d, Kaplan−Meier curves, including log-rank P value for EFS, in patients with a low IFNγ and low PD-L1 (n = 19) versus all other biomarker combinations (n = 26) (c), and in patients with a high IFNγ and high PD-L1 (n = 7) versus all other biomarker combinations (n = 38) (d). e-f, ROC curves for low IFNγ and low PD-L1 versus all other biomarker combinations (AUC = 0.565) (e), and high IFNγ and high PD-L1 versus all other biomarker combinations (AUC = 0.6) (f). The ROC curve analyses used a binary outcome (event within five years), since follow-up among all event-free patients was ≥58 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoeijmakers, L.L., Dimitriadis, P., Wijnen, S.C.M.A. et al. Neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in melanoma: 5-year survival and biomarker analysis from the phase 2 PRADO-trial. Nat Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04158-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04158-9