Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapies have the potential to transform treatment of autoimmune disease by resetting the immune system. However, adoption of cell therapies in the autoimmune space is limited by hurdles such as inpatient administration, lymphodepletion and safety concerns around cytokine release syndrome and non-specific immunosuppression. RNA-based cell therapy has potential to address these limitations. Here we report prespecified exploratory analyses from a successful placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized phase 2b trial in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis who received Descartes-08, an autologous, RNA-encoded anti-B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CAR-T cell therapy. In 66.7% of patients (n = 10/15), transient targeting of BCMA with Descartes-08 administered in an outpatient setting without lymphodepletion resulted in durable clinical efficacy. Comparison of Descartes-08-treated (n ≤ 19) and placebo (n ≤ 15) cohorts by flow cytometry, serum profiling, multiplexing cytokine analysis and bulk/single-cell transcriptional analysis reveals a precision retuning of self-reactivity demonstrated by increased pro-immune function, decreased activity of BCMA+ plasma cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells and reductions in disease-associated cytokines, such as IL-6. Furthermore, antibody and T cell receptor analysis revealed altered circulating repertoires of self-reactive antibodies and T cell clones among Descartes-08 participants. These effects occurred without immune suppression, indicated by the lack of decline in vaccine-specific antibodies or hypogammaglobulinemia. Our findings unveil a new type of immune reset and support the development of BCMA-targeted RNA cell therapies as a more accessible therapy for autoimmune diseases. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04146051.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although CD19 and CD20 antigens are expressed on most B cells, B cell maturation antigen (BCMA; TNFRSF17) is predominantly expressed on plasma cells (PCs) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), along with some memory B cells. As a result, BCMA has been targeted as a route to destroy pathogenic cells that are rare but have important roles in driving disease. During many autoimmune diseases, PCs secrete autoantibodies that drive disease, whereas pDCs secrete type I interferons that are potent inflammatory molecules. The high levels of BCMA expression on these cells and lack of BCMA on other cells, including most B cells, suggest new opportunities to control autoimmunity without the broad immunosuppression associated with targeting ubiquitous B cell antigens (Fig. 1a).

a, Schematic overview of the engineering process used to generate Descartes-08 (DC-08) CAR-T cells. b–d, Flow cytometric analysis of anti-BCMA CAR expression in engineered CD8+ T cells derived from both HDs and individuals with MG. Histograms (b) show surface anti-BCMA CAR expression frequency and MFI. Bar graphs show mean ± s.d. for expression frequency (c) and MFI (d) with all data points shown. Technical replicates were performed in triplicate. e,f, DC-08 mRNA copies per cell (e) and CAR expression (f) on DC-08 from representative HDs were measured via qRT–PCR and flow cytometry, respectively. Triplicate technical replicates were obtained for each sample. g, In vitro cytotoxicity assay using HD-derived DC-08 or unmodified control CD8+ T cells and MM.1S-GFP PC target cells at E:T ratios of 1:2, 1:8 and 1:32. Triplicate technical replicates were obtained for each sample. h,i, Cytotoxicity of DC-08 or unmodified control CD8+ T cells against primary autologous PCs as measured by flow cytometry. DC-08 and controls were derived from healthy (h) or MG (i) donors. Gates show percentages of CD8+ effector and CD27highCD8− PC populations. j–n, Preclinical analysis of DC-08 pharmacokinetics and efficacy in an immunocompromised mouse xenograft model. The study shown is one representative study of more than five analogous experiments with similar results. j, Representative flow cytometry plots of peripheral blood 1 day after T cell infusion (day 8) for analysis of anti-BCMA CAR expression in mice administered unmodified CD8+ T cells or DC-08. k,l, Percentage (k) and MFI (l) of CAR expression on propidium iodide−CD45+CD8+ cells for all mice (n = 5 per group) treated with unmodified CD8+ T cells or DC-08. Bar graphs show mean ± s.e.m. with all data points displayed. m,n, Control of MM.1S-Fluc malignant PC burden in xenograft mouse model after infusion of DC-08 or unmodified CD8+ T cells on day 7. Quantification (m) and images (n) of MM.1S-Fluc bioluminescence (n = 5 per group) are shown. P values were calculated using log-transformed data and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction; values in the figure show statistical significance at day 13. Line plot shows mean ± s.e.m. Source data are provided for this figure. rh, recombinant human. Panel a created with BioRender.com.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has transformed cancer treatment1, but approved therapies involve inpatient treatment, preconditioning chemotherapy and risk of toxicity and secondary malignancies. Recently, CAR-T cell therapy has entered the autoimmune space in clinical trials2. However, patients with autoimmunity have a different set of needs and tolerances to the risks and burdens associated with conventional CAR-T cell therapy. To drive widespread adoption, new cell therapies must address these limitations. Engineering of cells using RNA offers distinct advantages toward this goal by exploiting transient CAR expression. This characteristic enables dosing at levels that are immediately therapeutic and that exhibit a built-in proliferative check: CAR RNA degrades during cell division. As a result, RNA cell therapy can be administered without lymphodepletion and in the outpatient setting, also eliminating the risk of secondary malignancies because no genomic modification occurs. This set of features creates a biologic-like approach that involves an initial leukapheresis but is otherwise similar with respect to patient experience. Although targeting BCMA with traditional cell therapies has previously been associated with toxicity, transiently targeting BCMA+ cells could obviate toxicities associated with integrating vectors, including cytokine release syndrome, hypogammaglobulinemia and infections. Furthermore, because BCMA+ cells underpin many autoimmune diseases, this platform could contribute to accessible therapies without the broad immune cell depletion associated with antigens such as CD19.

Descartes-08 is an autologous RNA CAR-T cell therapy targeting BCMA. We recently reported potent and long-lasting clinical effects in a multicenter, open-label study of Descartes-08 after six once-weekly infusions in generalized myasthenia gravis (MG)3,4,5. Here and in a companion paper6, we report the results of a phase 2b, double-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) in patients with MG. The trial met the primary endpoint, with 66.7% of participants randomized to Descartes-08 achieving at least a five-point improvement in the MG Composite (MGC) score at month 3 compared to 27.3% of those randomized to placebo (P = 0.0472). Furthermore, Descartes-08 was associated with durable responses through 12 months without additional infusions. Here we describe underpinning correlative and mechanistic data associated with these outcomes that support a precision retuning, or reset, of autoreactivity. Preclinically, Descartes-08 was potent and well tolerated. Manufacturing of Descartes-08 at clinical scale was robust, and the cell product exhibited favorable phenotypes for CAR-T function. Relative to placebo infusion, biomarker analysis demonstrated that Descartes-08 elicits a targeted pro-immune effector response and preferentially reduces BCMA-high (BCMAhi) PCs and activated pDCs. These effects occurred without depletion of the broader lymphocyte compartments, immunoglobulins or vaccine titers. Changes in autoantibody profiles, single-cell transcriptional profiles and T cell receptor (TCR) clonality that were unique to the Descartes-08 cohort further support a targeted immune reset. Together, these studies demonstrate that coupling RNA engineering with BCMA targeting creates a precision CAR-T cell platform to achieve clinical effects in a manner more accessible to patients with autoimmune disease by avoiding inpatient administration, lymphodepletion and adverse events such as hypogammaglobulinemia.

Results

Descartes-08 T cells engineered with RNA target and destroy human BCMA+ targets

To confirm function, the Descartes-08 RNA payload was electroporated into CD8+ T cells. Twenty-four hours later, robust surface expression of anti-BCMA CAR was evident (Fig. 1b–d). CAR RNA was rapidly detected and then gradually waned to baseline (Fig. 1e), consistent with expression that peaked on day 1 (Fig. 1f). These cells exhibited potent antigen-specific killing of human BCMA+ target cells (Fig. 1g). Target engagement was also associated with effector cytokines production, including IFNγ and Granzyme B. Notably, this effect was not broadly inflammatory as other cytokines involved in MG, such as IL-6, were not elevated (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 1). Descartes-08 also efficiently depleted autologous PCs from healthy individuals or patients with MG (Fig. 1h,i and Supplementary Fig. 2). We next assessed functionality in a humanized xenograft model in which immunocompromised NSG mice are engrafted with human malignant PCs. One day after Descartes-08 infusion, CAR expression was detectable in more than 80% of circulating CD45+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1j–l). Furthermore, Descartes-08 cells controlled malignant PCs compared to unmodified T cells or untreated animals (Fig. 1m,n and Supplementary Fig. 3). These studies support Descartes-08 as an efficient and selective technology to deplete BCMA+ targets by harnessing transient engineering of T cells with RNA payloads.

Descartes-08 can be manufactured at scale with favorable properties for CAR-T cell therapy

Building on the above, we initiated a phase 2b RCT of Descartes-08 in patients with generalized MG. Patients underwent a single leukapheresis to collect cells used to prepare Descartes-08 (Fig. 2a) and then received six once-weekly infusions of Descartes-08 or placebo in an outpatient setting without preconditioning chemotherapy. Despite patients with diversity in antibody serotype and treatment history (see companion paper6), all analyzed lots (n = 35 of 36 patients randomized) exhibited consistent characteristics with favorable viability, CD8+ cell frequencies and CAR expression (Fig. 2b–d). Characterization of T cell markers on Descartes-08 lots indicated hallmark phenotypes associated with potent CAR-T cell function7, including central memory (TCM) and effector memory (TEM) T cells, along with (terminal) effector T cells (TTE) and T memory stem cells (TSCM) (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, the latter, TSCM cells, are mediators of efficient therapeutic function through plasticity and rapid proliferation8. T cells in Descartes-08 lots were not exhausted (TEX), as indicated by minimal co-expression of CD39, LAG3 and PD-1 (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, Descartes-08 can be manufactured from patients with diverse characteristics and exhibits favorable profiles for CAR-T cell therapy. Lastly, pharmacokinetic profiling using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR) revealed large, discrete increases in Descartes-08 RNA levels after infusion that were absent prior to infusion and at later times, such as month 3 (approximately 7 weeks after the final infusion) (n = 19) (Fig. 2f).

a, Schematic of the phase 2b, placebo-controlled RCT in patients with generalized MG. b–d, Graphs showing frequencies of DC-08 viability (b) measured by fluorescence microscopy and CD8 expression (c) or anti-BCMA CAR expression (d) measured by flow cytometry on lots of DC-08 produced for the RCT (n = 35). e, Graph showing the characterization of CD8+ T cell subsets in DC-08 lots characterized by flow cytometry, including TSCM, TCM, TEM, TTE and TEX subsets (n = 35). f, Quantitation of DC-08 mRNA in circulation of whole blood at indicated days (screen (SCR), day 1, month 1 and month 3) at pre-infusion (pre) or 30 minutes post-infusion (post) timepoints for participants randomized to the active DC-08 cohort (n = 19). Dotted line indicates LLOQ. Box-and-whisker plots show the median, interquartile range and full range of data, along with individual data points. Source data are provided for this figure. Panel a created with BioRender.com.

Descartes-08 preferentially reduces BCMAhi PCs and activated pDCs

To elucidate the mechanism behind the successful clinical outcome, on-target pharmacodynamics activity of Descartes-08 against BCMA+ target cells in patients was assessed by measuring the maintenance and activation status of plasmablasts (circulating precursors of PCs) and pDCs in circulation. The rarity of these cells—approximately two orders of magnitude lower than CD19+ B cells9—presents a challenge amplified by the localization of most PCs to the bone marrow. Thus, we first quantified plasmablast and pDC levels at screen relative to normal ranges10,11; both populations were within normal ranges (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). However, assessment of the function of these cells prior to treatment revealed that plasmablasts in patients with MG exhibited significantly higher expression BCMA—a key maintenance signal—compared to healthy donors (HDs; P = 0.007) (Fig. 3c). Other studies have also reported that, upon activation, PCs secrete high levels of antibody and increase BCMA expression12. Likewise, in assessing pDCs in patients with MG relative to HDs, CD86, a key activation marker, was also significantly increased (P = 0.002) (Fig. 3d).

a,b, Pretreatment (SCR) frequencies of plasmablasts (a; n = 9) and pDCs (b; n = 12) by flow cytometry with corresponding reference ranges for healthy individuals. Mean ± s.e.m. with all data points shown. c,d, Pretreatment MG versus HD BCMA protein expression on plasmablasts (c; MG, n = 9; HD, n = 10) and CD86 protein expression on pDCs (d; MG, n = 12; HD, n = 10), measured by flow cytometry. Data show MFI with mean ± s.e.m. with all data points shown. e,f, Flow cytometric analysis of absolute change in BCMA expression in plasmablasts at month 1 (n = 9 participants per group) and month 3 (placebo, n = 7; DC-08, n = 6) (e) or CD86 expression in pDCs at month 1 (n = 11 participants per group) and month 3 (n = 10 participants per group) (f) measured by MFI for placebo and DC-08 groups at month 1 and month 3 relative to respective SCR samples. g,h, Flow cytometric analysis of plasmablast (g) and pDC (h) frequency for placebo and DC-08 groups at month 1 and month 3 relative to respective SCR sample (sample sizes as per e and f). i, Heatmaps showing the Pearson correlation coefficient statistics (r) of comparisons between PhIP-Seq autoreactomes for longitudinal samples collected from placebo participants (n = 14) and DC-08 participants (n = 16). The series (left to right and top to bottom) is ordered by participant and then by timepoint (day 1, month 1 and month 3). Central diagonal indicates the correlation of each autoreactome against itself (providing r = 1 by definition). j, Assessment of autoantibody repertoire turnover via correlation of PhIP-Seq autoreactome for patients treated with placebo at month 3 (r value median = 0.89) (n = 14), DC-08 at month 3 (r value median = 0.72) (n = 16) and DC-08 at month 6 (r value median = 0.74) (n = 10) relative to respective day 1 autoreactome, showing a significant decrease in r value at month 3 in DC-08 participants relative to placebo (P = 0.034). k, Evaluation of the effect of leukapheresis on the autoantibody repertoire. Data show Pearson correlation coefficient (r) for all day 1 autoreactomes compared against participant-matched SCR autoreactome (r value median = 0.68) (n = 19). l, Evaluation of fold change in anti-AChR autoantibody titer against absolute change in clinical MG status (measured by MG-ADL scale) for comparison of month 3 against month 1 across placebo-treated and DC-08-treated participants with measurable anti-AChR titer at SCR (n = 21). m, Fold change in the level of anti-AChR binding antibody titer after treatment with placebo at month 3 (n = 11), DC-08 at month 3 (n = 13) and DC-08 at month 6 (n = 9) relative to respective day 1 titer for all participants with measurable anti-AChR titer at SCR. P values were generated with a two-sided unpaired t-test for each comparison between treatment groups and paired two-sided t-test between longitudinal timepoints within each treatment group. Box-and-whisker plots show the median, interquartile range and full range of data, along with individual data points. Source data are provided for this figure. D, day; M, month.

Because activated PCs secrete high levels of antibody and express higher levels of BCMA12, we hypothesized that activated PCs or plasmablasts in patients with MG chronically encountering autoantigen (for example, anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR)) would result in preferential deletion of these PCs relative to other PCs. Intriguingly, analysis of plasmablasts after Descartes-08 treatment revealed significant reductions in BCMA expression on plasmablasts at month 3 (n = 6) (P = 0.035) compared to placebo. Similarly, CD86 was significantly reduced on pDCs at month 1 (n = 11) (P < 0.001) relative to placebo and also trended downward at month 3 (Fig. 3e,f). Interestingly, at month 12, the decrease in CD86 levels persisted among the Descartes-08 cohort (Extended Data Fig. 2), although fewer samples were available at month 12 (n = 7). Despite the changes in activation state, the frequency of plasmablasts and circulating pDCs remained unchanged (Fig. 3g,h), consistent with the normal levels observed at screen (Fig. 3a,b). Therefore, both major circulating populations of BCMA+ target cells—plasmablast progenitors of PCs and pDCs—show abnormal expression of maintenance (that is, BCMA) and activation (that is, CD86) markers in our MG cohort. Administration of Descartes-08, but not placebo, normalizes both populations by a mechanism that may include preferential deletion of activated, BCMAhi populations.

Descartes-08 selectively retunes the autoreactive antibody repertoire

We observed a durable clinical effect long after Descartes-08 treatment ends (see companion paper6) and a preferential decrease of BCMAhi PCs (Fig. 3e), the source of autoantibodies. Thus, we reasoned that Descartes-08 might allow a precision retuning or reset of the antibody repertoire in which the self-reactive fraction of circulating antibodies is selectively pruned. To quantify changes in the repertoire of self-reactive antibodies, termed the ‘autoreactome’, we analyzed longitudinal serum samples from Descartes-08 and placebo RCT participants using a phage immunoprecipitation and sequencing (PhIP-Seq) assay in which all self-antigens in the human proteome are displayed13,14. Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r, indicates the level of similarity between autoreactomes: r = 1 indicates equivalence and r = 0 indicates disparity. Therefore, in paired longitudinal samples from any participant, a lower value for r indicates greater changes in the autoantibody repertoire. As expected from previous studies13,14, correlation matrices of 14 placebo and 16 Descartes-08 patients revealed minimal correlation of autoreactomes across participants but a high level of correlation when comparing longitudinal samples from a given placebo participant (Fig. 3i). By contrast, Descartes-08 was associated with a greater change in the autoreactome (r value median = 0.72) compared to placebo (r value median = 0.89) at month 3 compared to day 1; this change persisted through month 6 (r value median = 0.74) (Fig. 3j). As expected, leukapheresis, which occurs between screen and day 1, impacted all participants (both Descartes-08 and placebo), consistent with removal of a portion of circulating leukocytes (Fig. 3k). A caveat to these data is that, although we measured large changes in the autoreactome, the technique does not reveal the specific nature of the change. Anti-AChR antibodies attack the neuromuscular junction in MG and are an established diagnostic indicator. However, this parameter is not a biomarker to track disease progression. In line with this limitation, anti-AChR antibody titer did not correlate with change in clinical disease, as measured by the Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) scale (n = 21) (Fig. 3l and Extended Data Table 2). Furthermore, despite the dramatic changes in autoreactome, we did not observe a significant change in the anti-AChR antibody titer (Fig. 3m). Thus, although anti-AChR antibody is an important serotype classification tool, its relevance here as a quantitative marker of disease severity is limited15.

Descartes-08 preserves global immune populations, immunoglobulins and vaccine titers

Many approved biologic and CAR-T cell therapies target antigens that are widely expressed across the B cell compartment, such as CD19. Likewise, traditional CAR-T cell therapy and repeat dosing with T cell engagers targeting BCMA can induce global PC depletion. Beyond prevalence of antigen target, approved CAR-T cell therapies involve lymphodepletion. One impact of these combined characteristics is non-specific suppression spanning depletion of B cells, hypogammaglobulinemia, diminished vaccine titers and infection. By contrast, we hypothesized that the transient pharmacokinetics profile of Descartes-08 (Fig. 2f) may limit the pharmacologic activity to the most pathogenic BCMAhi cells—PCs and pDCs—while sparing most B cells. This strategy is consistent with our data above showing pruning of BCMAhi plasmablasts and highly activated pDCs (Fig. 3d–f). In line with our hypothesis, no significant changes were observed between placebo and Descartes-08 when assessing broad immune populations, including the change in frequency of B cells, T cells, natural killer cells and monocytes (Fig. 4a–e and Supplementary Fig. 8). Likewise, total immunoglobulins (Fig. 4f–h and Extended Data Table 3) and common vaccine titers (Fig. 4i–m and Extended Data Table 4) were preserved at month 3 and month 12. Thus, although patients exhibited long-lasting clinical responses at month 12 and reduced BCMA among plasmablasts (Fig. 3e), vaccine titers and immunoglobulins were spared. This is consistent with the hypothesis that activated PCs in patients with MG chronically encountering autoantigen (for example, AChR) exhibit increased BCMA expression, resulting in preferential deletion by Descartes-08.

a–e, Change in CD19+ B cells (a), CD20+ B cells (b), T cells (c), natural killer (NK) cells (d) and monocytes (e) as measured by flow cytometry at month 3 in placebo patients (n = 10), at month 3 in DC-08 patients (n = 11) and at month 12 in DC-08 patients (n = 7) compared to SCR. f–h, Change in immunoglobulin G (f), immunoglobulin A (g) and immunoglobulin M (h) titers at month 3 in placebo patients (n = 15), at month 3 in DC-08 patients (n = 19) and at month 12 in DC-08 patients (n = 13) compared to SCR. i–m, Change in anti-measles (i), anti-mumps (j), anti-rubella (k), anti-diphtheria (l) and anti-tetanus (m) vaccine titers at month 3 in placebo patients (n = 15), at month 3 in DC-08 patients (n = 19) and at month 12 in DC-08 patients (n = 13) compared to SCR. n–ab, Change in abundance of serum factors analyzed by Olink Target 96 Inflammation panel and expressed as difference in log2-scaled NPX between indicated timepoint and respective SCR sample. n, Change in abundance of significantly changed inflammatory factors, along with additional analytes of interest at day 1 (n = 19). Significant changes in LTA (P < 0.001), β-NGF (P = 0.006), TGF-β1 (P < 0.001), CD6 (P = 0.010) and IL-7 (P = 0.018) occurred after leukapheresis (n = 19). o–t, Change in abundance of inflammatory factors, including IL-6 (o), IL-24 (p), CCL19 (q), ARTN (r), RANKL (s) and VEGFA (t), after treatment with DC-08 compared to month 3 in placebo patients (n = 10) and DC-08 patients at month 1 (n = 11), month 3 (n = 11) and month 12 (n = 7). Decreases in IL-6 (P = 0.019) and IL-24 (P = 0.008) occurred at month 3 in DC-08-treated patients relative to placebo (o,p). u–x, Change in abundance of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 (u), CCL19 (v), RANKL (w) and VEGFA (x), in the DC-08 patient cohort between clinical responders at month 1 and month 3 (n = 6) and non-responders at month 1 and month 3 (n = 5). RANKL was significantly reduced in responders at month 1 (P = 0.035) and month 3 (P = 0.030) (w). y–ab, Change in abundance of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 (y), CCL19 (z), RANKL (aa) and VEGFA (ab), in the DC-08 patient cohort between patients who had not received prior treatment with biologics (that is, complement inhibitors, FcRn inhibitors or CD19/CD20-targeting antibodies) at month 1 and month 3 (n = 5) and patients who had received prior biologics at month 1 and month 3 (n = 6). IL-6 (P = 0.010), CCL19 (P = 0.002) and VEGFA (P < 0.001) were significantly decreased at month 1 in patients who had not received biologics prior to DC-08 (y–ab). Additionally, VEGFA was significantly decreased in patients who had not received biologics prior to DC-08 at month 3 (P = 0.003). For lymphocyte subsets, immunoglobulin titers and vaccine titers, P values were generated with a two-sided unpaired t-test for each comparison between treatment groups and a paired two-sided t-test between longitudinal timepoints within each treatment group. For cytokine analysis, P values were generated using a linear mixed-effects model. Box-and-whisker plots show the median, interquartile range and full range of data, along with individual data points. Source data are provided for this figure. NS, not significant.

In light of the preservation of immunoglobulins and vaccine titers, we next tested if Descartes-08 modulated a panel of 92 cytokines characteristic of disease and therapeutic effects during MG. As all patients undergo leukapheresis for Descartes-08 manufacturing, we first measured the effect of leukapheresis at day 1 relative to screen (n = 19) (Fig. 4n). Leukapheresis did not impact several cytokines relevant to autoimmune disease; for example, IL-6 is associated with clinical disease in MG16, and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) is often expressed on pDCs that secrete inflammatory type I interferons during many autoimmune diseases17. However, leukapheresis did cause significant changes in lymphotoxin alpha (LTA) (P < 0.001), nerve growth factor beta (β-NGF) (P = 0.006), latent transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) (P < 0.001), CD6 (P = 0.010) and IL-7 (P = 0.018), but these levels returned to pre-leukapheresis levels by month 3. Descartes-08 infusion was not associated with indicators of CAR-T cell therapy-induced inflammation. Notably, we observed changes in several cytokines relevant to therapeutic effects after Descartes-08 infusion but not after placebo infusion (Fig. 4o–t). In particular, IL-6, IL-24, CCL19 and artemin (ARTN), all of which are involved in autoimmunity, decreased at month 3 as well as at month 1 and month 12 for some analytes. Importantly, IL-6 is a key indicator of MG severity, and this cytokine was significantly reduced at month 3 in patients receiving Descartes-08 (P = 0.019). These findings are further connected to the reduced BCMA levels that we measured on plasmablasts (Fig. 3e), because IL-6 promotes survival in PCs18,19. Likewise, IL-24 and CCL19 are overexpressed in many autoimmune diseases and contribute to disease progression20,21,22. Furthermore, elevated levels of ARTN have been linked to inflammation and nerve damage23. Interestingly, we discovered that several other analytes relevant to autoimmune inflammation and immune reset decreased at month 12, including EN-RAGE, TRAIL and TNFSF14 (LIGHT), as did TGF-β1, which is involved in immune reset after CAR-T cell therapy24,25,26,27,28,29 (Extended Data Fig. 3). This is notable as CAR expression is transient after Descartes-08 infusion (Fig. 2f). We also analyzed patient subgroups among the Descartes-08 cohort, although power was lower (Fig. 4u–x). RANKL was significantly reduced in responders at month 1 (P = 0.035) and month 3 (P = 0.030) (Fig. 4w), which might reflect the ability of Descartes-08 to target pDCs that often express RANKL30. Changes in other analytes, IL-6 (Fig. 4u), CCL19 (Fig. 4v) and VEGFA (Fig. 4x), were difficult to interpret in this subgroup owing to the number of samples. Next, we classified patients as having prior exposure to biologics if their treatment history included complement inhibitors, FcRn inhibitors or CD19/CD20-targeting antibodies. This analysis revealed that IL-6 (P = 0.010), CCL19 (P = 0.002), RANKL and VEGFA (P < 0.001) were all lower at month 1 in patients who had not previously received biologics (Fig. 4y–ab). However, RANKL did not reach the level of statistical significance as a function of biologics treatment history. Regarding VEGFA, this protein is also often elevated during autoimmune disease31. Thus, the decrease in IL-6 (Fig. 4y), CCL19 (Fig. 4z), RANKL (Fig. 4aa) and VEGFA (Fig. 4ab) is consistent with therapeutic effects in autoimmunity. These changes may create opportunities to identify patients well suited for therapy.

Descartes-08 administration and clinical response are associated with altered transcriptomic signatures

We next used bulk sequencing and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to assess changes in protein expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients at screen and month 3. Enumeration of cell populations using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis of samples from all analyzed patients in placebo (n = 7) and Descartes-08 (n = 7) cohorts showed consistent representation of immune cells before and after treatment (Fig. 5a). This stable distribution aligns with the precision targeting of a rare fraction of BCMA+ cells and the data in Fig. 4a–m confirming preservation of immune cells, immunoglobulins and vaccine titers. As with the flow cytometry analysis of circulating cells (Fig. 4a–e), the composition of BCMA+ cells (plasmablasts and pDCs) from screen to month 3 was similar between placebo and Descartes-08 treatment groups. Notably, however, among patients treated with Descartes-08, responders exhibited a reduction in plasmablasts and pDCs compared to non-responders (Fig. 5b,c). These results, possibly enabled by increased sensitivity of the scRNA-seq technique, are supportive of our findings in the full Descartes-08 cohort showing that treatment reduces BCMAhi cells and decreases pDC activation (Fig. 3e,f). Likewise, although there was no substantial difference in regulatory T (Treg) cell composition from screen to month 3 between placebo and Descartes-08 cohorts, within the Descartes-08 group there was an increase in Tregcells among responders and a decrease among non-responders (Fig. 5d). Treg cells maintain balance within the immune system by limiting effector CD4+ T cell subsets that mediate autoimmune responses; these cells are often reduced in MG and other autoimmune diseases32. These post-treatment cell dynamics highlight differences between Descartes-08 and placebo cohorts, between responders and non-responders and between pathogenic BCMA+ cells (that is, plasmablasts and pDCs) and beneficial immune cells (that is, Treg cells). Notably, these effects occurred while global immune populations, immunoglobulins and vaccine titers were protected.

Transcriptomic analysis of peripheral blood using bulk sequencing (placebo, n = 6; DC-08, n = 14; responder, n = 9; non-responder, n = 5) and scRNA-seq (placebo, n = 7; DC-08, n = 7; responder, n = 5; non-responder, n = 2). a, UMAPs of integrated samples from all analyzed patients in placebo and DC-08 cohorts at SCR and month 3 timepoints showing minimal visual change between cell subsets across timepoints or treatment groups. b–d, Relative percent change from SCR to month 3 in plasmablast (b), pDC (c) and Treg (d) composition. Box-and-whisker plots show the median, interquartile range and full range of data, along with individual data points. e, Bulk RNA-seq GSEA of hallmark gene sets. f–h, scRNA-seq GSEA of hallmark gene sets in plasmablasts (f), pDCs (g) and Treg (h) cells showing enrichment of pro-immune gene sets in patients treated with DC-08 relative to placebo and in responders compared to non-responders. i–n, scRNA-seq GSEA of B cell subsets (B cells (i), naive B cells (j), intermediate B cells (k) and memory B cells (l)) and T cells (CD8+ T cells (m) and CD4+ T cells (n)). Asterisks (*) in heatmaps indicate statistical significance at P values indicated in the inset. Genes were considered differentially expressed at an FDR < 0.1 (Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons) and an absolute log2(fold change) > 0.585 (1.5-fold change). Further details on statistical analyses are provided in Methods. Source data for b–d are provided for this figure. HSPC, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; ASDC, AXL+SIGLEC-6+ dendritic cell; cDC1, conventional type 1 dendritic cell; cDC2, conventional type 1 dendritic cell; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DN, down; dnT, double-negative T cell; Eryth, erythrocyte; gdT, gamma-delta T cell; MAIT, mucosal-associated invariant T; Mono, monocyte; NES, normalized enrichment score; UP, up; UV, ultraviolet.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of hallmark pathways identified enrichment of numerous pathways after Descartes-08 treatment that correlated with clinical response in both bulk RNA-seq (Fig. 5e) and scRNA-seq (Fig. 5f–n) analyses. Bulk RNA-seq functional enrichment analysis from stabilized whole blood revealed distinct differences between placebo (n = 6) and Descartes-08 (n = 14) cohorts as well as between responders (n = 9) and non-responders (n = 5) within the Descartes-08 cohort (Fig. 5e). Several of these upregulated pathways—including IFNα, IFNγ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling to NF-κB, IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling and inflammation—are associated with pro-immune effector function and enable identification of key functional pathways whose enrichment correlates with clinical response. Single-cell RNA-seq from PBMCs revealed that BCMA+ target cell populations, plasmablasts and pDCs, along with beneficial Treg cells, each exhibited an enrichment of pro-immune gene signatures in patients treated with Descartes-08 (n = 7) that was absent in placebo (n = 7) (Fig. 5f–h). Notably, apoptotic genes were also upregulated among plasmablasts in patients receiving Descartes-08 (Fig. 5f). Together, these signatures reinforce on-target modulation that we measured in BCMA+ plasmablasts (that is, decreased BCMA levels) and pDCs (that is, reduced activation) using flow cytometry (Fig. 3e,f) and autoantibodies using PhIP-seq (Fig. 3i,j). We also measured upregulation of TNF signaling to NF-κB in plasmablasts, which can restrict PC function in the bone marrow and decreases the number of circulating antibody-secreting cells33. TNF signaling was also upregulated in pDCs among Descartes-08 recipients; this activity has been demonstrated to reduce production of IFNα34. In addition, IFNγ signaling was upregulated in Treg cells, which is transiently produced during immune responses and can suppress the proliferation of antigen-presenting cells and other pathogenic T cells35. Discrete pathways were also enriched within responders (n = 5) and non-responders (n = 2) that are consistent with reduced pathogenicity among PCs and pDCs (Fig. 5f–h). These included a reduction in proliferation (Myc targets v1/v2; Fig. 5f) and inflammation (TNF; Fig. 5f) in responders, findings that further connect pathway modulation with clinical effect. Regarding other cell types, we observed an enrichment of pro-immune pathways in B cells (Fig. 5i–l and Extended Data Fig. 4) and T cells (Fig. 5m,n and Extended Data Fig. 5). In addition to CD8+ T cells, clear differences in transcriptional profiles existed between Descartes-08-treated and placebo cohorts in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5n), and these differences in pro-immune signatures were further amplified when assessing responders and non-responders among Descartes-08 recipients. This may indicate that Descartes-08 exerts a bystander activation effect on the CD4+ T cell compartment. Because this month 3 timepoint is after the interval of CAR expression, another possibility is a return to homeostasis after depletion of target cells undergoing chronic stimulation; the latter can create suppressor T cell cytokines and populations. However, additional work will be required to determine if Descartes-08-mediated reduction of pDC or PC activity, in tandem with the reduced IL-6 that we measured (Fig. 4o), might help release T cells from some degree of immunosuppression. Taken together, although we did not see global changes in absolute or relative cellularity of immune compartments, transcriptomic analysis reveals systemic alteration of immune status associated with Descartes-08 infusion relative to placebo, on-target effects in plasmablasts and pDCs and unique signatures among Descartes-08 responders and non-responders.

Descartes-08 remodels the TCR repertoire without dramatic changes to circulating T cell phenotypes

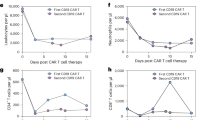

Because of the altered transcriptional profiles among CD8+ T cells just mentioned, we evaluated the TCR repertoire in circulation of a subset of patients. TCR sequencing revealed that Descartes-08 increases clonal expansion and contraction compared to placebo (Fig. 6a,b). Notably, the Descartes-08 cohort exhibited expansions and contractions in many TCR clonotypes from day 1 to month 2 relative to the placebo cohort (Fig. 6c,d). Representative scatter plots for the Descartes-08 group confirmed that many of these newly expanded clones at month 2 were not present at day 1, and cross-comparison of clonotypes with the paired Descartes-08 product showed that few, if any, could have derived from the autologous Descartes-08 product (Fig. 6b). These findings are consistent with the scRNA-seq data (Fig. 5m,n) as NF-κB plays an important role in T cell activation—including receptor signaling and co-stimulation—associated with increased TCR dynamics36 (Fig. 6c,d). We also used flow cytometry to assess changes in T cells at screen, month 1 and month 3 after the first infusion (Fig. 6e–m and Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). These measurements revealed similar CD8+ T memory subsets to the product analysis (TSCM, TCM and TEM) as well as T helper subsets (Th1, Th2 and Th17) and CD4+ T memory subsets (TSCM, TCM and TEM). A decrease in Th2 was observed at month 1 in patients who received Descartes-08 but not placebo (P = 0.014) (Fig. 6f). In addition, there was an upward trend in the frequency of CD8+ TSCM at month 3 (Fig. 6h). Otherwise, these analyses did not identify significant changes (Fig. 6e,g–m). Aside from Th2, the frequency within each T cell subset was similar between Descartes-08 and placebo cohorts (Fig. 6e–m). Together, these data indicate that Descartes-08 alters the TCR repertoire without significantly changing the broader phenotypic composition of the T cell compartment.

a,b, TCR repertoire profiling of participants assigned to placebo (a) and DC-08 (b) cohorts comparing day 1 baseline and month 2. Scatter plots showing frequencies of individual TCR-β sequences in peripheral blood. Dotted and dashed diagonal lines show parity and two-fold changes. Significantly expanded or contracted TCR-β clonotypes are indicated with blue and yellow color, respectively. Significance is determined by a fold change greater than 2 and FDR-adjusted P < 0.01. For DC-08-treated participants, clonotypes found in DC-08 product are indicated with a thick outline. c,d, Frequencies of expanded (c) and contracted (d) clonotypes in placebo (n = 5) and DC-08 (n = 10) participants. Dataset was computationally downscaled to 100,000 templates to control for variation in sequencing depth between samples. e–m, Comparative frequencies of indicated T cell subsets (including Th1, Th2 and Th17 (e–g), along with CD4+ and CD8+ TSCM (h,k), TCM (i,l) and TEM (j,m)) in PBMCs at month 1 and month 3 expressed as fold change from SCR. PBMCs were analyzed from anti-AChR antibody seropositive participants for placebo (n = 10) and DC-08 (n = 11). In c and d, P values were generated by square root transformation of the data and a two-sided unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. In e–m, y axes are log2 scale, and P values were generated by log transformation of data and two-sided multiple t-tests with correction for multiple comparisons (Benjamini, Krieger, Yekutieli with a 5% FDR). Box-and-whisker plots show the median, interquartile range and full range of data, along with individual data points. Source data are provided for this figure.

Discussion

Descartes-08 targets BCMA+ cells, among which PCs and pDCs are most abundant9; these are also populations involved in autoimmune pathogenicity, including PCs that produce autoantibodies in MG37. An intriguing observation in our trial is that, although we observed a large clinical effect in patients receiving Descartes-08 relative to placebo, we observed only subtle changes in the broader B cell compartment, vaccine titers and immunoglobulins. Instead, we discovered multiple on-target effects associated only with Descartes-08, including decreases in BCMAhi PCs and activated pDCs, decreases in PCs and pDCs in responders compared to non-responders, remodeling of autoantibody repertoires, amelioration of key disease-associated cytokines, modulation of T cell activity—including increased Treg cells—and altered transcriptional profiles of PCs and pDCs between Descartes-08 and placebo recipients and between responders and non-responders. Although some changes in cytokines associated with Descartes-08 did not persist at month 12, others, such as IL-6 and RANKL, did persist or did not become evident until this time (EN-RAGE, TRAIL and TNFSF14), even though CAR expression persists only for a period of days. These combined findings suggest a type of precision immune reset or retuning—different from those associated with integrating vectors and lymphodepletion38—achievable with a transient BCMA-directed intervention without widely reported adverse events or immune suppression. Additional studies will help define unique or shared mechanisms dependent on design choices such as antigen, vector stability (for example, DNA and RNA) and the use of lymphodepletion.

The precision reset above may occur through one or multiple mechanisms warranting future study, but it paves the way for BCMA as a safe target with important practical implications in the setting of autoimmunity. Potential mechanisms could involve precision ablation (for example, direct cytotoxicity) or interference (for example, trogocytosis) on the BCMAhi subset comprising pathogenic PCs and other cells such as pDCs. This action could result in alteration of pathogenic autoantibodies or modulation of the pathogenic subset of T cells and induction of counter-regulatory mechanisms. Such preferential targeting may occur in patients with autoimmune disease because PCs specific for pathogenic self-antigens receive chronic stimulation, resulting in increased activity and secretion of autoantibodies. During their development to long-lived PCs, activated precursors upregulate BCMA to enable cell maintenance12. Functionally, therefore, Descartes-08 may preferentially deplete PCs expressing high levels of BCMA, which, in patients with autoimmune disease, is preferential to PCs producing pathogenic autoantibodies. An alternative hypothesis is that other cell types, such as less mature B cells, upregulate BCMA during the pathologic stimulation in autoimmunity39,40 and that targeting these cells stops pathology. Directly testing these hypotheses is a clinical challenge in the context of autoimmunity because the key target cells are predominantly located outside of circulation—PCs resident in the bone marrow and activated pDCs and B cells in inflamed tissue or lymphatics11,37,41,42,43. These are unique challenges compared to oncology, where bone marrow aspirates, for example, are often obtainable. Indeed, one key feature of Descartes-08 as a BCMA-targeting cell product may be an inherent cellular ability to access and perform effector function specifically in the relevant pathological tissue. Although these gaps remain, our findings of Descartes-08-specific changes in PCs, pDCs, cytokine and transcriptomic signatures and autoantibody repertoires provide support for activity outside of the circulation and key avenues for future investigation.

To our knowledge, this is the first placebo-controlled trial in cell therapy for autoimmunity, and this phase 2b RCT creates a unique opportunity to isolate drug-specific mechanistic effects. The data reveal that Descartes-08 stimulates changes in the TCR repertoire that are distinct from product TCR clones, decreases MG-associated cytokines (for example, IL-6)44 and reduces maintenance and activation of PCs and pDCs; these effects are absent in the placebo cohort and are achieved without non-specific depletion of immune cells, immunoglobulins or vaccine titers. This selectivity contrasts with the burden of conventional CAR-T cell therapies that broadly, although transiently, suppress immunity through lymphodepletion and often by targeting widely expressed antigens (for example, CD19)2,45,46. Descartes-08 also induces substantial remodeling of the autoantibody repertoire that does not occur in the placebo cohort. Furthermore, clinical response correlates with enrichment of pro-immune gene pathways that are important in functional T cell immunity47. This precision retuning of autoreactivity is associated with significant clinical responses that persist long after Descartes-08 infusion (that is, 12 months). The nature of this mechanism appears different from cellular immune resets recently described with CAR-T cell therapies involving DNA-based/integrating vectors targeting CD19 (ref. 38). However, a confounding factor in comparing these technologies is the use of lymphodepletion in other studies that non-specifically ablates the immune compartment. In the autoimmune space, emerging cell therapies are exploring less invasive preconditioning regimes that could enable better comparison. These regimens still ablate the immune compartment with a ‘hard’ reset, but repopulation is faster without immediate recurrence of disease in the small number of patients reported. However, relapses have been reported, and the invasiveness is significant for a patient with autoimmunity. The relative implications of these elements—and the long timescale of autoimmune disease that could necessitate redosing—will be important to assess with clinical trials. Our current work demonstrates mechanistic changes that correlate with safe and long-lasting clinical effects in patients treated with Descartes-08 relative to placebo.

Descartes-08’s mechanism of targeting BCMA is distinct from several recently approved and emerging therapeutic classes used in the treatment of MG and other autoimmune diseases. These technologies include FcRn inhibitors and complement inhibitors that directly target circulating antibodies and antibody effector function, respectively; both technologies involve ongoing treatment to maintain effect48,49,50. Further, emerging T cell therapies often involve lymphodepletion, viral vectors and targeting of CD19 that result in non-specific depletion of B cells and, consequently, immunoglobulins and vaccine titers2,45,46. In MG, some of these approaches have reported declines in anti-AChR titers but also lead to broader immunosuppressive effects51,52. Relative to Descartes-08, the examples above have fundamentally different mechanisms involving broad reduction of antibodies or broad depletion of B cells. In our approach using transient targeting of BCMA without lymphodepletion, we did not observe a decrease in anti-AChR antibody titers nor was there a correlation with clinical effect. This finding is consistent with clinical literature demonstrating that anti-AChR is an important tool to classify MG disease but is not a validated biomarker for monitoring progression53,54.

An emerging body of work is uncovering features of autoantibodies that contribute to their pathology in a way not explained by magnitude (that is, titer) alone. Such features include affinity, antibody classes and subclasses and engagement of effector functions that are not commonly measured in clinical assays55,56,57,58. Thus, one limitation of our study is the use of the clinical radioimmunoassay to assess the quantity of AChR autoantibody titers; this assay is well established for clinical study but does not provide detailed analysis. Future studies could employ cell-based assay—for example, cells displaying specific AChR ligands—to capture rich data of binding affinity and effector function for diverse serum anti-AChR autoantibodies55,59. This information could reveal differences in Descartes-08 and placebo patients or before and after Descartes-08 treatment. These data may also clarify the connection between the dramatic change we observed in the self-reactive antibody profile (that is, autoreactomes) relative to the measured AChR titers and considerations related to confirmational clones that cannot be detected by PhIP-Seq. More broadly, improved resolution of AChR titers may be useful in monitoring progress of RNA cell therapies, along with CAR+ cells during and after infusion, and the reduction of disease-associated cytokines (for example, IL-6).

In this report, we show notable mechanistic and functional differences in patients receiving Descartes-08 and placebo that support the differential clinical outcomes between these two cohorts. The specific changes in immune signatures—evidenced by T cell sequencing, phenotypic and cytokine analysis, autoreactivity profiling and transcriptional changes—without broad suppression support a precision immune reset that results in durable clinical improvements. These findings underscore the potential of Descartes-08 as a platform to combat MG or other autoimmune diseases in which autoantibodies drive disease.

Methods

Preclinical in vitro experiments

Generation of CAR cells and evaluation of CAR expression

Primary CD8+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs of HDs or patients with MG using the Miltenyi Biotec CD8 MicroBeads kit, following the manufacturer’s positive selection protocol. In brief, single-suspension PBMCs were incubated with CD8 MicroBeads and passed through an LS column placed in a magnetic field; unlabeled cells were washed away, and the positively selected CD8+ T cells were eluted. Selected T cells were cultured in X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% human AB serum (GeminiBio) and GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a density of 1 × 106 cells per milliliter. Recombinant human IL-7 and IL-15 (Proteintech) were added at 100 ng ml−1 each, and 25 ng ml−1 OKT3 (Takara Bio, anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody) was added on culture day 0 to initiate T cell activation and expansion. Culture was monitored every 3–4 days for cell density and viability. Cytokine-supplemented media were added as needed to maintain cell culture density at 1 × 106 cells per milliliter. After culture, activated T cells were transfected with Descartes-08 mRNA. After transfection, CAR expression was assessed by flow cytometry using APC-conjugated recombinant human BCMA (BCMA-APC; ACROBiosystems). Transfected cells were washed with FACS buffer (PBS + 2% FBS), stained with propidium iodide and BCMA-APC for 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark, washed again and analyzed by flow cytometry (Cytek Biosciences, Guava easyCyte 12HT). Data analysis was performed using guavaSoft version 3.3 and FlowJo version 10.8.1 software.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Target cells

For in vitro cytotoxicity assays, target cells included MM.1S-GFP cells, generated by lentiviral transduction of a GFP cassette into MM.1S cells (American Type Culture Collection) and autologous plasma cells differentiated from memory B cells in PBMCs obtained from HDs or individuals with MG. For in vitro experiments, sample sizes were chosen to achieve statistical power based on historical study data5,60.

Memory B cell isolation and plasma cell differentiation

Memory B cells were isolated from frozen PBMCs using the Memory B Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) via magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Enrichment purity (>90%) was confirmed via flow cytometry using CD19 (BioLegend, clone 4G7) and CD27 (BioLegend, clone O323). Enriched B cells were CD19+ and CD27+. Plasma cells were differentiated from memory B cells according to the method by Jourdan et al.61,62. Enriched memory B cells were expanded in complete IMDM (Gibco) supplemented with FBS (VWR), GlutaMAX (Life Technologies), CpG 2006 (Invivogen), soluble CD40L (R&D Systems), HA-tag monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems) and IL-2, IL-10 and IL-15 (PeproTech) at a culture density of 0.3 × 106 cells per milliliter in 24-well plates for 4 days. Expanded B cells were assessed for proliferation and phenotype and then cultured in plasmablast differentiation media (supplied with IL-2, IL-10 and IL-15 (PeproTech) and IL-6 (Miltenyi Biotec)) for 3–4 days at 0.5 × 106 cells per milliliter. Plasmablasts were then differentiated to plasma cells using differentiation media (IL-6, IL-15 and IFNα, all Miltenyi Biotec) for an additional 3–4 days. Final plasma cells were phenotyped via flow cytometry using CD19 (BioLegend, clone 4G7), CD27 (BioLegend, clone O323), CD38 (BioLegend, clone HIT2), CD138 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, clone 300506) and CD269 (Miltenyi Biotec, clone REA315). Example gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Cytotoxicity assay

MM.1S-GFP cells were co-cultured with Descartes-08 or unmodified CD8+ T cells at an effector:target (E:T) ratio of 1:2, 1:8 and 1:32 in a 96-well V-bottom plate. After overnight incubation, plates were centrifuged (400g, 5 minutes), and cell pellets were stained with propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) for viability before proceeding with flow cytometry (Cytek Biosciences, Guava easyCyte 12HT). Cytotoxicity was quantified, and percent killing was calculated as the percentage decrease in viable MM.1S-GFP cells relative to control wells (MM.1S-GFP cells alone without effector cells). Differentiated plasma cells were co-cultured with autologous Descartes-08 or control CD8 T cells at an E:T ratio of 2:1 in 200 μl of complete IMDM media in 96-well U-bottom plates. After overnight incubation, plates were centrifuged (400g, 5 minutes). Cell pellets were stained with propidium iodide for viability, CD8-FITC (Beckman Coulter, clone B9.11) for Descartes-08 identification and CD27-PE (BioLegend, clone O323) to identify plasma cells. Cytotoxicity was quantified by flow cytometry (Cytek Biosciences, Guava easyCyte 12HT), and percentages of effector cell and target cell populations were analyzed and plotted using FlowJo version 10.8.1 software. Example gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Cytokine analysis

Supernatant samples from MM.1S-GFP and Descartes-08 co-culture were used for LEGENDplex Human CD8/NK Panel (13-plex) bead array (BioLegend), conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, standards and supernatant samples were incubated with fluorescence-encoded beads precoated with cytokine-specific capture antibodies in a 96-well V-bottom plate. After incubation, the plate was washed, and detection antibodies were added to form a sandwich complex. Streptavidin-PE was then added to bind biotinylated detection antibodies, generating a fluorescent signal proportional to the concentration of each analyte. Fluorescent signal was analyzed using a flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences, Guava easyCyte 12HT), and data were processed using the LEGENDplex Data Analysis Software Suite (BioLegend). Cytokine concentrations were interpolated from standard curves.

In vitro pharmacokinetics

For in vitro pharmacokinetics, thawed Descartes-08 cells were incubated at 37 °C in complete medium and sampled at indicated timepoints for assessment of CAR protein expression and Descartes-08 RNA content. CAR protein expression was evaluated as described above. Descartes-08 mRNA was evaluated by qRT–PCR. Total RNA was extracted from Descartes-08 using an miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript IV with oligo(dT) primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to synthesize cDNA. Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, ABI PRISM 7000). Gene-specific primers were used to amplify the target gene, and expression levels were normalized to housekeeping gene GAPDH. Sample sizes were chosen to achieve statistical power based on historical study data60.

Preclinical in vivo experiments

Animals

Female NSG mice (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1wJ1/SzJ), aged 6–8 weeks, were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at Noble Life Sciences. Mice were maintained in individually ventilated microisolator cages with sterilized bedding, water and food. The vivarium environment was continuously monitored to ensure temperature (18–22 °C), humidity (35–65%) and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animals were monitored twice daily for clinical signs of illness or distress. Animals exhibiting signs of severe morbidity, including inability to feed or drink or more than 20% body weight loss, were humanely euthanized in accordance with institutional guidelines. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Noble Life Sciences and conducted under the oversight of a licensed veterinarian and in compliance with all applicable local, state and federal guidelines. The institution holds an active Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) assurance. Sample sizes were chosen to achieve statistical power based on historical study data60. The study shown is one representative study of more than five analogous experiments with similar results.

Tumor engraftment

On study day 0, for tumor engraftment, NSG mice were injected intravenously via the tail vein with 2 × 106 MM.1S-Fluc cells stably expressing firefly luciferase, a gift from Y. S. Tai (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). On study day 6, tumor burden was assessed by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) using the IVIS Spectrum Imaging System (PerkinElmer) after intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin (150 mg kg−1). Animals were then randomized into treatment groups based on tumor signal intensity to ensure equal tumor burden across testing groups. IVIS imaging was analyzed using Living Image version 4.7.3.20616.

Test article injection and assessment

On study day 7, mice were treated via tail vein intravenous injection with either 10 × 106 unmodified CD8 T cells or Descartes-08, with a group where no test articles were injected (MM.1S-Fluc-alone group) as control. Malignant PC (multiple myeloma) progression was monitored by BLI through day 13. Body weight and clinical observations were recorded throughout the study to assess treatment tolerability and animal health.

PBMC analysis post-test article injection

On study day 8, 100 µl of peripheral blood was collected from each animal via submandibular bleed into EDTA-coated tubes to prevent coagulation. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer, followed by quenching via high-serum buffer (X-VIVO 15 media + 25% FBS) and then washing in FACS buffer (PBS + 2% FBS + NaAzide). Single-suspension cells were stained with propidium iodide as well as fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific to human CD45 (BioLegend), CD8 (BioLegend) and BCMA-APC (ACROBiosystems) for 30 minutes at 4 °C in the dark. After FACS buffer washing, samples were acquired on a flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies, NovoCyte 3000), and data were analyzed using Agilent NovoExpress version 1.6.1 software. Live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter and viability dye (propidium iodide) exclusion, followed by gating on human CD45+CD8+ events to identify CAR+ cells.

Clinical trial

MG-001 part 3 was a prospective, double-blind, multicenter, randomized placebo-controlled phase 2b trial evaluating the safety and clinical activity of Descartes-08, RNA-engineered anti-BCMA CAR-T, in adults with generalized MG. Of the 45 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 36 were eligible to be randomized after meeting manufacturing specifications, of whom 20 were assigned to the active Descartes-08 arm, and 16 were assigned to the placebo arm. All participants underwent leukapheresis and manufacturing of autologous CAR-T product. A single apheresis was sufficient to reach the target dose of 52.5 × 106 viable CAR+ cells per kilogram ± 45% for each of six once-weekly infusions. Starting on day 1, participants received the six once-weekly doses of Descartes-08 or placebo. One of the participants randomized to Descartes-08 withdrew from the study for reasons other than safety or efficacy after two infusions, and subsequent labs were not analyzed; therefore, 35 total randomized patients were analyzed in the correlative/mechanistic study. Clinical efficacy was evaluated through determination of MGC and MG-ADL scores and a clinical response threshold set at a ≥5-point drop on the MGC scale. Full details are provided in the companion paper6. Differences among the data available for the clinical efficacy (modified intention-to-treat) population with respect to clinical assessment visits versus sample availability (for example, quantity and timepoints) prevented exact alignment between the two datasets in all cases.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines and applicable governmental regulatory standards. Independent institutional review boards provided written approval of the protocol and amendments. All participants provided written informed consent. The protocol is provided in the companion paper6. Sex was self-reported by participants. There were no sex-based analyses prespecified, and none was conducted post hoc due to small sample size.

Manufacturing of Descartes-08

Participants underwent leukapheresis to isolate PBMCs, which were subsequently processed and manufactured into Descartes-08 under Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines. Descartes-08 product characterization was performed according to validated release testing methods. Viability testing used an automated cell counter (Nexcelom Bioscience, K2 Cellometer) to detect viable and non-viable cells stained with acridine orange and propidium iodide, respectively. Characterization of CD8 expression and CAR expression was performed by staining of cells with CD8-APC (Beckman Coulter, clone B9.11) and recombinant human BCMA (ACROBiosytems), respectively, and analysis by flow cytometry.

Clinical biomarker analysis

Blood sample collection

Patient research samples were collected throughout Descartes-08 treatment after obtaining written informed consent. A variety of blood products and derivatives was collected, including PBMCs, serum and Tempus tube stabilized RNA. Serum was processed from peripheral whole blood using clot activator Vacutainer collection tubes. Serum was stored at −80 °C until ready for use. PBMCs were isolated from peripheral whole blood by Ficoll gradient separation. Isolated PBMCs were resuspended in a final concentration of 7% DMSO and cryopreserved until ready for use.

Flow cytometry: product analysis (CAR expression, CD8)

Flow cytometry was used to understand phenotypes of Descartes-08 products. Samples of Descartes-08 product lots were retained for exploratory use and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. Cells were thawed and washed in a high-protein medium. Cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and washed prior to cell subset staining. Samples were then resuspended in a Fc receptor blocking solution (BioLegend) and left to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. Panel-specific antibodies were added to blocked product cells and incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes. Stained cells were washed and resuspended in 200 µl of FACS buffer (DPBS + BSA + NaAzide). At least 50,000 events were recorded. All flow cytometry experiments were conducted using the Agilent NovoCyte 3000 flow cytometer. All experimental analysis was performed in Agilent NovoExpress version 1.6.1 software. Memory T cell populations were defined as follows: TCM CD3+CD4−CD8+CD28+CD45RO+, TEM CD3+CD4−CD8+CD28−CD45RO+, TSCM CD3+CD4−CD8+CD28+CD45RO− and TTE CD3+CD4−CD8+CD28−CD45RO−. Cell activation was characterized by co-expression of CD39, LAG-3 and PD-1 on CD3+ cells, as determined by fluorescence minus one (FMO) and isotype controls. Representative gating schemes were prepared using FlowJo version 10.8.1 software. Gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. All product phenotyping data were normalized to percent of CD3+ T cells ((count in gate X / count in CD3+ T cell gate) × 100). All data points presented are from single measurements.

Flow cytometry: PBMC phenotyping

Flow cytometry was used to understand changes in cell composition before and after Descartes-08 therapy. Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and washed in a high-protein medium. PBMCs were first stained with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and washed prior to cell subset staining. PBMCs were then resuspended in an Fc receptor blocking solution (BioLegend) and left to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. Panel-specific antibodies were added to blocked PBMCs and incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes. Stained cells were washed and resuspended in 200 µl of FACS buffer (DPBS + BSA + NaAzide). At least 40,000 events were recorded for T cell subset and TBNK panels. At least 100,000 events were recorded for B cell and dendritic cell panels due to low frequencies of populations of interest. All flow cytometry experiments were conducted using the Agilent NovoCyte 3000 flow cytometer. All experiment analysis was performed in Agilent NovoExpress version 1.6.1 software. Cell populations were defined as per the following table with gating strategies shown in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 (prepared using FlowJo version 10.8.1 software). The full antibody list is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Flow cytometric definition of immune cell populations is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

BCMA and CD86 surface protein expression were measured using median fluorescence intensity (MFI) on single-parameter histograms. HD ranges for circulating peripheral blood and pDC frequencies were obtained from literature10,11. Other data on HDs were obtained by flow cytometric analysis of PBMCs from a panel of HDs (demographics provided in Supplementary Table 3). All CD8+ T memory, CD4+ T memory, T helper and TBNK data were normalized to percent of live cells ((count in gate X / count in live cell gate) × 100). pDC data were normalized to both percent of live cells ((count in pDC gate / count in live cell gate) × 100) and percent of dendritic cells ((count in pDC gate / count in dendritic cell gate) × 100). Peripheral blood data were normalized to percent of B cells ((count in peripheral blood gate / count in CD19+ gate) × 100). Data were excluded for peripheral blood quantitation and BCMA MFI measurements if peripheral blood count was less than three events. For longitudinal analysis, change in cell frequency was calculated using fold change from screen (normalized population frequency at month X / normalized population frequency at screen). Change in MFI was calculated using delta change from screen (MFI at month X − MFI at screen). All data points presented are from single measurements.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Whole blood was collected at clinical sites in Tempus RNA preservation tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at −80 °C until processing. RNA extraction was performed using the Tempus Spin RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and used to generate cDNA using the SuperScript IV cDNA Synthesis Kit and oligo-dT primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of circulating RNA from CAR-T cell product by quantitative PCR

Measurement of Descartes-08 CAR RNA in whole blood was performed by qRT–PCR using gene-specific primers on cDNA extracted from Tempus whole blood tubes. Reactions were set up using a hydrolysis probe assay (forward primer: ATGGATGGGCTGGATCAACA; reverse primer: GGTGTCCTCGTACTTCAGGT; hydrolysis probe: /{5′FAM}/ACCAGGGAGCCCGCCTACGC/{3′TAMRA}, all from Integrated DNA Technologies) and TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on an AriaMx Real-Time PCR System (Agilent Technologies). A standard curve prepared with linearized plasmid containing the amplicon was used to quantitate copy number of cDNA in each reaction, and values were normalized to circulating quantity in blood. Reactions, standard curve and no template control (NTC) were performed in triplicate and averaged for analysis. Values lower than the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) were substituted with 2 for the purpose of data display.

PhIP-Seq

All PhIP-Seq was performed similarly to a previously published multichannel protocol:

https://www.protocols.io/view/derisi-lab-phage-immunoprecipitation-sequencing-ph-czw7x7hn?step=14.1

As previously described63, this human peptidome library consists of a custom-designed phage library of 731,724 unique T7 bacteriophages each presenting a different 49-amino-acid peptide on its surface. Collectively, these peptides tile the entire human proteome including all known isoforms (as of 2016) with 25-amino-acid overlaps. One milliliter of phage library was incubated with 1 µl of human serum (from each of the n = 279 samples) overnight at 4 °C and immunoprecipitated with 25 µl of 1:1 mixed protein A and protein G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 10008D and no. 10009D). These beads were then washed, and the remaining phage–antibody complexes were eluted in 1 ml of Escherichia coli (EMD Millipore, BLT5403) at 0.5–0.7 optical density and amplified by growing in a 37 °C incubator. This new phage library was then reincubated with the same individual’s serum, and the previously described protocol was repeated. DNA was then extracted from the final phage library, barcoded and PCR amplified, and Illumina adaptors were added. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was then performed using an Illumina sequencer to a read depth of approximately 1 million per sample. To control for background binding of phage directly to protein A or protein G, we also performed the identical experiment but did not include any antibody or human samples. We performed 79 of these ‘mock-IPs’.

Analysis of PhIP-Seq

As previously described, NGS reads from FASTQ files were aligned at the level of amino acids using RAPSearch2. All human peptidome analysis was performed at the gene level, in which all reads for all peptides mapping to the same gene were summed, and 0.5 reads were added to each gene to allow inclusion of genes with zero reads in mathematical analyses. Within each individual sample, reads were normalized by converting to the percentage of total reads. To normalize each sample against background non-specific binding, a fold change over mock-IP was calculated by dividing the sample read percentage for each gene by the mean read percentage of the same gene for the 79 mock-IP A/G bead-only controls. This fold change signal was then used for side-by-side comparison between samples and cohorts. As previously described14, overall changes in the autoreactome across time were determined by comparing the complete fold change over mock-IP signal across all genes in each individual against each other sample using a Pearson correlation. The Pearson correlation coefficient r values were then used for downstream quantitative analyses.

Evaluation of AChR titers, vaccine titers and total immunoglobulin titers

Autoantibody titers, immunization titers and immunoglobulin levels were measured in patient serum by a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory (Quest Diagnostics). AChR antibody titers were measured by radioimmunoassay. Diphtheria, tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella and varicella zoster virus antibody titers were measured by immunoassay. Neisseria meningitidis antibody titers were measured by a multi-analyte immunodetection assay. An immunoglobulin panel (IgA, IgG and IgM) was measured by an immunoturbidimetric assay. If the assay resulted in a value below the LLOQ, LLOQ / 2 was used for calculations of relative change from baseline for that data point. If the assay resulted in a value above the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ), ULOQ was used for calculation of relative change from baseline for that data point.

Analysis of inflammatory proteins via the Olink Target 96 Inflammation assay

Proteomic analysis was performed on patient serum using the Olink Target 96 Inflammation assay, which measures the relative abundance of 92 proteins per sample. Serum was isolated from whole blood collected from Descartes-08 patients at clinical sites and was prepared, stored and handled according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were randomized on a 96-well plate prior to analysis, and 16 bridging samples (independent of the internal controls) were used per plate to combine multiple runs into a single experiment. Sample analysis was performed at Psomagen on an Olink Q100 instrument. All samples analyzed passed standard quality control metrics, and, therefore, zero samples were excluded from analysis. Data processing and preliminary analysis were performed using Olink NPX Signature version 2.0.2 software. Data from the Olink assay were quantified as NPX values (an arbitrary relative quantitation unit on a log2 scale). Patient samples were analyzed at month 1, month 3 and month 12. For two patients without month 3 samples available (one treated with Descartes-08 and one treated with placebo), data were imputed from month 2 samples. For longitudinal analysis of relative abundance of the 92 assayed proteins, baseline NPX values were subtracted from longitudinal NPX values (that is, ΔNPX = NPXtimepoint 2 – NPXtimepoint 1).

Statistical analysis of Olink Target 96 Inflammation results

To assess statistical significance, a linear mixed-effects model (lmer) was performed for each protein using the Olink Analyze package, an R package from Olink that provides tailored statistical analysis of standard Olink data outputs, to analyze how different variables interact to impact longitudinal trends. The linear mixed model used followed the general structure of NPX ~ A × B + (1 | ID), where NPX is the output of the Olink assay, A and B are fixed effects and ID accounts for random effects and is an array of unique identifiers for each patient. To analyze the effects of leukapheresis, NPX values at day 1 and screen timepoints were entered into the model, and timepoint was used as the fixed variable. To analyze the effects of treatment with Descartes-08 compared to placebo, NPX values at month 3 and screen timepoints were entered into the model, and treatment and timepoint were used as the fixed effects. To analyze the effects of treatment at timepoints without a corresponding placebo timepoint, NPX values at month 1 or month 12 and screen timepoints were entered into the model, and timepoint was used as the fixed variable. To analyze the effects of treatment within subgroups defining clinical response or prior treatment with biologics, NPX values at month 1, month 3 or month 12 and screen timepoints were entered into the model, and timepoint and clinical response or biologics treatment, respectively, were used as fixed variables.

RNA-seq analysis

Transcriptomic analysis via RNA-seq

Transcriptomic analysis at screen and month 3 timepoints was performed on mRNA from whole blood with RNA-seq. First, mRNA was extracted followed by cDNA synthesis from stabilized whole blood (see ‘RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis’). NGS libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA library kit per the manufacturer’s protocol followed by sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq X Plus system at 40 million paired reads per sample. Library preparation and sequencing were performed at Psomagen.

Transcriptomic analysis via scRNA-seq

Transcriptomic analysis at the single-cell level was performed on PBMCs using scRNA-seq. In brief, cDNA and NGS libraries were prepared from cryopreserved PBMCs isolated from whole blood (see ‘Blood sample collection’) and were processed with Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5′ HT Reagent Kits v2 per the manufacturer’s protocol. The NGS libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq X Plus system at a minimum of 20,000 reads per cell. Sequencing was performed at Psomagen.

scRNA-seq data processing and quality control

scRNA-seq data from the Descartes-08 MG-001 clinical trial were processed using the Seurat package (version 5.0+)64 in R (version 4.3+). For each sample, raw count matrices were assessed for quality at the cellular and gene level. Cell-level metrics included the number of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), the number of detected genes and the percentage of reads mapping to mitochondrial and ribosomal genes. Cells were filtered based on established thresholds for these metrics. To ensure data integrity, ambient RNA contamination was estimated and removed using SoupX65, and potential cellular doublets were identified and excluded using scDblFinder66. Filtered datasets from all samples were then merged for integrated downstream analysis.

Normalization, clustering and cell type annotation of scRNA-seq results

The integrated dataset was normalized and variance stabilized using the SCTransform method67. To mitigate technical batch effects between samples, we applied Harmony’s68 integration workflow. Principal component analysis was performed on the top 2,000 highly variable genes, and the first 30 principal components were used for UMAP visualization and for constructing a nearest neighbor graph.