Abstract

Infertility is a global health challenge affecting millions worldwide, and in vitro fertilization (IVF) remains the main treatment option. The increasing demand for IVF necessitates innovations that improve access, efficiency and outcomes. To address this need, we developed a microfluidic device (FIND-Chip) that automates the isolation and denudation of oocytes from follicular fluid (FF), a critical step in IVF workflow. In a clinical study involving 582 patients from four IVF centers, FIND-Chip was utilized to perform automated oocyte recovery from FF and revealed that in more than 50% of the cases functional and mature oocytes are inadvertently discarded under current clinical practice. These undetected oocytes successfully developed into high-quality blastocysts, thereby substantially expanding the embryo pool available for patients’ treatment. Notably, an oocyte that was retrieved by FIND-Chip from a clinically screened and discarded FF sample led to a live birth, highlighting the potential of microfluidic automation to enhance IVF success rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

IVF is a well-established method to treat infertility, a prevalent global condition affecting 8% to 12% of reproductive-aged couples worldwide1,2,3. Since the birth of the first baby conceived with IVF in 19784, IVF outcomes have steadily improved, largely because of transformational innovations including medically controlled ovarian stimulation5, improved embryo culture conditions6, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)7 and vitrification of gametes and embryos8. Despite notable advancements, the success rate of IVF is at best 50% for good prognosis patients, but can be more challenging for many others, in particular those with low oocyte yield resulting from poor ovarian reserve9. In addition, IVF continues to depend heavily on manual processes and complex workflows in the embryology laboratory. IVF clinics must employ a highly skilled workforce and stringent quality control measures to reduce variabilities in clinical outcomes10, which increase costs and reduce accessibility of treatment. Given the persistent gap between patient demand and access to treatment, IVF success rates, and the emotional and financial burden of repeated cycles, IVF clinics will need to implement more efficient and automated solutions to meet the need for infertility treatments in the coming decades11.

The success of an IVF cycle is closely linked to the number of oocytes retrieved following ovarian stimulation12,13,14. IVF laboratory workflow starts with FF screening for the recovery of oocytes, a laborious task conducted by trained embryologists. Briefly, an embryologist scans the collected FF under a microscope to identify and recover the oocytes, typically found embedded in cumulus tissue layers called cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs). This process is challenging because of the complex composition of FF, which contains varying amounts of blood cells, clots and nontarget tissue fragments, including epithelial, thecal and cumulus tissue. Despite recent innovations to automate various procedures in the IVF laboratory15,16,17,18,19 and the critical importance of recovering all available oocytes for patient treatment, FF screening continues to be performed manually, unchanged over the past four decades.

Microfluidic technologies enable precise manipulation, sorting and capture of cells from biological samples, facilitating the automation and standardization of the processes. Thus far, microfluidic applications in fertility treatment have been explored for sperm selection20,21,22, egg selection23,24 and denudation25,26, embryo selection and culture27,28, and vitrification29,30. However, FF with its nontarget tissue complexity and large sample volumes, poses challenges beyond traditional microfluidics capabilities. Although there have been recent advancements in processing very large volumes of biological fluids for the isolation of rare target cells31, to our knowledge, the isolation of oocytes from FF has so far remained an unsolved challenge.

Here we report an automated microfluidic-based device for isolating oocytes from FF and demonstrate its potential impact to clinical management of infertility. FIND-Chip (microfluidic isolation and denudation chip) automates the following tasks: (1) captures COCs from FF, (2) removes excess fluid and small nontarget debris, (3) denudes and washes the oocytes in a cyclical manner, and (4) releases the denuded oocytes in a dish ready for ICSI or cryopreservation. This process is controlled by an automated instrument that regulates fluid flow, ensuring that oocytes from different samples experience the same fluidic forces and mechanical treatment. FIND-Chip can isolate and denude oocytes with high efficiency, while maintaining their viability and development potential. Importantly, processing of pre-screened FF by FIND-Chip revealed that human oocytes are frequently missed by manual processing during IVF cycles. FIND-Chip recovered a total of 583 oocytes from the screened and discarded FF samples of 582 patients, indicating a potential compromise to patient care, particularly for those with low oocyte yield, because of limitations in the current standard of care. Notably, in a pilot trial with 19 patients, 2 gained additional blastocysts for their treatment using oocytes that were recovered from pre-screened FF and returned to clinical workflow. One of these patients had a live birth outcome from an oocyte recovered using FIND-Chip—an oocyte that would have otherwise been discarded.

Results

FIND-Chip design and optimization

FIND-Chip is designed to process unscreened FF and produce isolated and denuded oocytes that are ready for fertilization or cryopreservation. After processing tens of milliliters of FF, the device yields a droplet (100 to 500 µl) containing denuded oocytes (Fig. 1a). FF varies widely among patients and clinics because of differences in patient physiology, stimulation protocol and laboratory practices, including retrieval techniques, follicle flushing and the use of anticoagulants in the collection tubes. FIND-Chip is designed to accommodate these variations among samples, such as differences in hematocrit levels, tissue content and sample viscosity. The fluidic protocol is standardized via automation to ensure process consistency. During the development and validation of FIND-Chip, we utilized hundreds of human FF samples obtained from various clinics to confirm cross-sample compatibility.

a, FIND-Chip automates oocyte screening in the IVF laboratory by processing FF and presenting denuded and isolated oocytes that are ready for fertilization or cryopreservation. b, FIND-Chip is composed of four modules that: filter the complex tissue-dense FF sample, denude oocytes using flow-oscillation cycles, concentrate the oocyte suspension by approximately 100 times, and capture oocytes in a deterministic location on the chip for enrichment. c, Top: FIND-Chip processed bovine oocyte fertilization rate after conventional insemination compared to manually denuded and undenuded control oocytes. Each data point represents an experiment starting with 20 to 25 oocytes (*P = 0.0261; ***P = 0.0009; NS, P = 0.4491). Middle: Percentage of fertilized embryos that could grow into blastocysts, where each data point represents the continuation of an experiment from the left-hand panel. n = 4 biological replicate with at least two technical replicates per biological replicates (NS, P = 0.0906, 0.1018, 0.9996). Bottom: blastomere counts were quantified using the fluorescently stained blastocysts. Each data point is a blastocyst that was analyzed. n = 3 biological replicates (NS, P = 0.7749; **P = 0.0017; *P = 0.0227). Normality was assessed and was not rejected by Shapiro–Wilk’s test (P = 0.1451 (left panel), P = 0.0722 (middle panel) and P = 0.9789 (right panel)). Two-tailed Brown–Forsythe and Welch one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons without any adjustments were used for all panels. Scale bars: 100 µm. Bar graphs show mean values and error bars show standard deviation. NS, not significant. Illustration in a created using BioRender.com.

FIND-Chip consists of four microfluidic modules, each performing a specific task: (1) filter, (2) denuder, (3) concentrator and (4) capture (Fig. 1b). The filter module initially holds the large, millimeter-scale tissues and prevents them from proceeding further into the chip. The captured tissues in the filter module include both target (COCs) and nontarget material such as blood clots, epithelial and thecal tissue. The filtration size cutoff starts at a 3-mm gap size between posts and gradually reduces to a final gap of 169 µm. These gap sizes were selected to allow trapping of COCs during sample loading at various filter stages, and the eventual release of oocytes after hyaluronidase (HYA) treatment when they are stripped from the cumulus tissue and only retain their tight corona layer. The concentrator module removes approximately 85% of the FF volume through side channels and reduces the flow rate going into the capture module. This module utilizes size exclusion and inertial focusing (that is, passive, size-based movement of particles in microchannels32) to ensure all COCs (and similar sized tissue) proceed downstream, while side channels siphon smaller nontarget cells (primarily red blood cells). The capture module is designed to retain the oocytes under steady flow, while letting the remaining fluid and smaller debris pass through. To accomplish this, the filtration size cutoff in the capture module gradually reduces from 188 µm to 108 µm. The capture module is separated into two sections, coarse capture (C-Cap) and fine capture (F-Cap), with a size cutoff of 175 µm between them. Although the oocytes would be distributed between the two sections early in the process (that is, first denudation cycle), all oocytes are eventually isolated in F-Cap after denudation. This enables less tissue debris to carry-over to the product during release. The denuder module, located between the filter and concentrator modules, consists of parallel channels that are sized closer to the oocyte diameter, and contain polygonal extrusions on the walls to facilitate denudation. These extrusions, initially proposed for steady flow in one direction25, are designed to effectively denude oocytes in both flow directions to take full advantage of a cyclical flow pattern during the denudation (Extended Data Fig. 1).

The FIND-Chip process was developed using bovine COCs (bCOCs) mixed into discarded human FF and optimized to achieve high isolation and denudation efficiencies (Extended Data Fig. 2). The functionality of isolated, denuded bovine oocytes was validated by conventional insemination with bull sperm, and subsequent monitoring of embryo development. Embryo development was compared across three conditions: (1) undenuded bCOCs (cumulus intact), (2) manually denuded oocytes and (3) FIND-Chip denuded oocytes. There were no statistically significant differences in fertilization and blastocyst development rates between FIND-Chip processed oocytes and manually denuded oocytes (Fig. 1c), indicating no adverse effects of the FIND-Chip process on oocyte viability. Because conventional insemination was used for fertilization in this experiment, the difference in fertilization rate between undenuded and denuded oocytes was expected, although the blastocyst development rates showed no statistically significant difference between any of the test conditions. To assess blastocyst quality, blastomere counts were quantified by Hoechst nuclear staining in a subset of bovine blastocysts developed until day 8. The mean ± s.d. blastomere counts of the bovine blastocysts developed from undenuded bCOCs (n = 29), manually denuded COCs (n = 27) and FIND-Chip denuded COCs (n = 26) were significantly different at 120.3 ± 5.3, 111.4 ± 11.1, and 118.7 ± 7.7 respectively. The undenuded control and FIND-Chip bovine blastocysts had significantly higher cell numbers than blastocysts from manually denuded oocytes (Fig. 1c) indicating better blastocyst quality. Notably, the FIND-Chip group exhibited more homogeneous blastomere counts than the manually denuded group and closely resembled the undenuded control group. This suggests that the FIND-Chip method induces minimal and uniform levels of stress during the isolation and denudation processes, unlike manual pipetting, which may introduce variability in mechanical stress.

Technology validation with FF samples containing human oocytes

The FIND-Chip process was validated using donated patient COCs spiked in the same patient’s pre-screened FF. Oocytes were donated from patients undergoing routine IVF who were consented through an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol. Twenty-one consented patients, with high oocytes yields (>20), each donated between one and four COCs to the study depending on their clinical oocyte count (Supplementary Table). The goal of this study was to confirm that all human oocytes spiked into FF were fully denuded and isolated in the capture module after the process (Fig. 2a).

a, Left: human COCs typically exhibit a large cumulus tissue. These donated COCs were spiked back in the same patient’s pre-screened FF. Middle: during sample loading, COCs are captured in the filter module because of their large cumulus tissue. Right: after the process, oocytes are fully denuded in the capture module and are ready to be released. b, All (or more) donated human oocytes are recovered during clinical FF processing experiments using FIND-Chip (n = 21 biological replicates). The first set of experiments (n = 13, P1 to P13) were conducted without staining the donated oocytes, whereas in the second set (n = 8, P14 to P21) of experiments donated oocytes were stained before spiking. c, All human oocytes that FIND-Chip recovered in an experiment (P16) where donated oocytes were stained: four donated (fluorescent) and three extra (nonfluorescent). Scale bars: 150 µm (a (left and middle), c), 50 µm (a (right)). I, input; O, output.

Remarkably and unexpectedly, the FIND-Chip device repeatedly recovered more human oocytes from the FF samples than the number of donated oocytes that were spiked in. In our initial experiments (n = 13 patients), we recovered 19 extra oocytes in addition to 39 donated oocytes originally spiked in the FF (Fig. 2b). To unambiguously distinguish between the donated oocytes and the extra oocytes recovered by the FIND-Chip process, in subsequent experiments we fluorescently stained the donated oocytes before spiking. Consequently, we were able to identify both groups by fluorescence imaging after oocytes were released from the chip (Fig. 2c). In these experiments (n = 8 patients), we recovered 100% (23 of 23) of the stained donated human oocytes, while observing a total of 8 extra oocytes (Fig. 2b). This outcome was consistent with our observations during system characterization experiments using bovine oocytes spiked into FF samples (Extended Data Fig. 2c) where we frequently identified human oocytes isolated from the pre-screened FF among bovine oocytes (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Clinical utilization of extra oocytes for IVF treatment

In a pilot clinical study, extra oocytes recovered by FIND-Chip were returned to clinical workflow and utilized for patient treatment. Consented patients underwent a standard egg retrieval procedure, their FF was manually screened and the eggs that could be identified were collected by an embryologist per the routine protocol. The pre-screened FF was then processed with FIND-Chip to search for extra oocytes. On average, there was a 30-min interval between the start of egg retrieval, manual screening and FF being marked as ‘discard’ and designated as available for processing by FIND-Chip. Any extra oocytes found were returned within ~45 min to the patient’s available oocyte pool for treatment.

In line with our previous examination, we consistently recovered oocytes that were not identified by routine manual screening. In this oocyte return study, we processed pre-screened FF from 19 patients and found at least one extra oocyte in 11 of them (57.9%). In total, the FIND-Chip was able to contribute 23 extra oocytes for an overall increase of 10.2% (23 of 225) in the oocyte pool (Fig. 3a). Of the 23 oocytes, 12 (52%) were metaphase II stage (MII), and were subsequently used in the patient’s ICSI procedure. Fertilization rates post-ICSI were similar between the FIND-Chip group and the manual screening group, 66.7% and 70.3% respectively (Fig. 3b). The percentage of fertilized oocytes that made it to the early blastocyst grade and above was 63% in the FIND-Chip group compared to 49% in the manual screening group. The quality of blastocysts was assessed on days 5, 6 and 7 (per Gardner criteria33) per the clinic’s standard protocol by the embryologist on duty who was not part of the research team. The embryologists were not blinded to whether embryos came from manual screening or the FIND-Chip because FIND-Chip oocytes or embryos were tracked separately as required by the IRB protocol. Per the routine protocol, the embryos with sufficiently high grades were selected for cryopreservation. In the FIND-Chip group, 4 of the 5 blastocysts (80%) were selected for freezing compared to 39 of 60 (65%) in the manual screening group (Fig. 3b). The grades of the embryos did not indicate any difference between the FIND-Chip group and the manual screening group (Fig. 3c). Because of low patient numbers, no statistical comparisons were performed between groups and the presented results are descriptive. Although a larger cohort is needed for a fully powered analysis of the recovered extra oocytes, preliminary findings indicate that the FIND-Chip contributed extra usable embryos, increasing the likelihood of successful outcomes.

a, Extra oocytes were found in more than half of the pilot study patient cohort (11 of 19). The majority of these oocytes were mature (12 of 23) and were returned to the patients’ treatment pool and fertilized by ICSI. b, Fertilization and blastocyst development rates (Gardner Grade 2 early blastocysts and above) of extra oocytes were on par with oocytes recovered using manual screening (standard of care), resulting in high-grade frozen embryos that are made available for transfer to the patient. 2PN, single cell zygote with 2 pronuclei; 2EB+, all blastocyst embryos including early blastocysts. c, Grading of human blastocysts selected for cryopreservation after recovery of oocytes via manual and FIND-Chip screening methods based on Gardner scoring system33. The manual screening group includes only blastocysts from patients for whom at least one FIND-Chip blastocyst was available. aPatient 1 had this blastocyst from an extra oocyte, which was transferred resulting in a live birth. bPatient 2 had preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy performed. Abn, chromosomally abnormal embryo; Eup, euploid embryo after testing; SOC, standard of care.

Overall, in this pilot study the FIND-Chip increased the number of embryos available for transfer in two patients. Notably, three extra frozen blastocysts were added for patient 1 who had six embryos from manual screening (50% increase), and one frozen blastocyst was added for patient 2 who had six embryos from manual screening (16.7% increase). Patient 2 had selected preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy to be performed on their embryos, and the extra blastocyst was assessed as euploid.

Remarkably, one of the extra oocytes that the FIND-Chip recovered resulted in a live birth for patient 1. Briefly, patient 1 underwent two frozen single blastocyst transfers, with both blastocysts initially graded as high quality. The first blastocyst transfer was from the manual screening group and failed to result in pregnancy. The second blastocyst transfer was from a FIND-Chip group that led to a successful pregnancy and resulted in a live birth, from an oocyte that was recovered in the FF that was discarded after clinical screening.

Multiclinic investigation of extra oocyte recovery from pre-screened FF

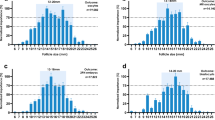

The prevalence of recovering extra oocytes from clinically screened FF was further investigated through the processing of discarded samples from multiple clinics. Briefly, we received discarded FF samples from four IVF clinics, operated under different networks, all accredited by the College of American Pathologists and listed in the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology database. Medium to large clinics, per patient volume, were selected to evaluate samples handled by a higher number and range of clinicians and embryologists. Overall, this study includes FF samples from clinics with a total of 39 clinicians performing the egg retrieval procedure and 61 embryologists scanning the FF. We acquired all available FF samples after egg retrievals were completed and were agnostic to the patient’s age, specific IVF treatment, hormonal response levels and clinical oocyte count. In agreement with the general patient population across these clinics, our cohort had a median patient age of 36 and a median clinical oocyte count of 12 (Extended Data Fig. 4).

The FIND-Chip recovered one or more extra oocytes in 54.3% of the pre-screened FF, from a cohort of n = 582 patients from these clinics (Fig. 4). We grouped the frequency of extra oocytes with respect to the clinical oocyte count (Table 1). Notably, the FIND-Chip recovered extra oocytes in all groups, including patients with a ‘very low clinical count’ (clinical oocyte count = 0–5) for whom the extra oocyte frequency was 35.0%. In this group, a maximum of five extra oocytes were recovered from a patient who had three oocytes from manual screening. In patients with a ‘low clinical count’ (clinical oocyte count = 6–11), the extra oocyte frequency was 51.5%, and a maximum of 11 extra oocytes were recovered from a patient who had 9 oocytes from manual screening. In the ‘moderate to high clinical oocyte count’ patient groups (clinical oocyte count = 12–17, 18–24 and >24), the extra oocyte frequency improved to 59.5%, 61.8% and 65.6% respectively. Of note, the full volume of the pre-screened FF was processed only for a fraction (31.8%) of individuals, primarily to allow testing of more samples from different patients (Methods).

Clinically screened and discarded FF samples were collected from four IVF clinics and processed by FIND-Chip to recover more oocytes. Extra oocytes were recovered from 316 of the 582 unique patient samples processed. One or more extra oocytes were recovered (y axis) across all patient groups that had both low and high number of oocytes recovered in standard clinical screening (x axis).

More than half of the extra oocytes recovered by the FIND-Chip were mature oocytes that can rapidly be returned to clinical workflow for patient treatment (Table 1). Of all the extra oocytes recovered from the pre-screened FF, 41.2% and 9.1% were at the metaphase II (MII) and metaphase I (MI) stages respectively; 36.3% were at the germinal vesicle stage; and the rest (13.4%) were marked as other, indicating fragmented or deformed. Fragmented or deformed oocytes refer to eggs with morphological abnormalities that preclude ICSI because of cytoplasmic fragmentation, irregular oolemma or zona, or are dead. Processing of these atypical oocytes did not impair device operation. The maturity distribution was generally maintained across different clinics.

Discussion

The automated technology presented in this study, which is agnostic to the visual appearance and recognition of the oocyte, allowed the recovery of extra oocytes that were not discernible to trained embryologists when scanning the complex FF milieu. Our experiments showed that extra oocytes are found in more than 50% of cases, independent of operator-related factors, and in many instances even after double manual screening of the FF. This is particularly pertinent, because one participating clinic routinely re-examined the already screened FF in all cases with fewer than ten oocytes, and in another clinic, we invited embryologists to manually rescreen FF without time constraints. In both cases, we were able to isolate extra oocytes, indicating the superior efficiency of the FIND-Chip system to identify and recover oocytes. Notably, the extra oocytes were recovered with the same consistency in samples from four independent clinics that had differences in standard clinical practices such as the use of anticoagulants during retrieval and time allocated for retrieval per patient. Based on the results in Table 1, we observed no significant variations in the recovery of extra oocytes between clinics despite the differences in practice. These results support the long-standing assertion that automated technologies are poised to improve the productivity of IVF laboratories, standardize care across clinics and increase the number of patients who can be treated with the same workforce34.

Despite numerous recent innovations in the IVF field such as microfluidic sperm selection tools35, automated ICSI technologies15 and machine learning-based embryo selection methods19,36, the number of viable oocytes remains as a decisive factor for treatment success12,13. To improve oocyte yield, efforts to date have focused on the development of new ovarian stimulation agents, which have produced variable results37,38,39. By simply finding more oocytes in the FF, we demonstrate that the microfluidic automation approach can have high potential impact for ultimate treatment success. The strong positive correlation between the oocyte yield and clinically observed cumulative live birth rate (CLBR) is well established by multiple retrospective studies across different clinics with large patient cohorts40,41. In a recent report41 in which 16,474 patients were tracked, the clinical outcome of ‘one or more live births’ using the oocytes from the index retrieval cycle was reported as: 14% (167 of 1,227) in patients who had 1–3 oocytes, 34% (1,672 of 4,933) in patients who had 4–9 oocytes, 53% (2,077 of 3,936) in patients who had 10–14 oocytes, 65% (3,091 of 4,729) in patients who had 15–25 oocytes and 74% (1,216 of 1,649) in patients who had >25 oocytes. Using the raw data from this study (provided by request from the authors), we plotted the increase in the CLBR per oocyte, and how the corresponding CLBR would shift upward when extra oocytes are available for the patients (Fig. 5)41. For patients with a low oocyte yield from manual screening, the impact of extra oocytes on the CLBR is substantial. On the other hand, for patients with a higher number of oocytes, extra oocytes would increase the available options toward higher-grade embryos and support achieving a subsequent pregnancy from a single retrieval, helping patients complete their nuclear family14. In addition to these analyses, considering patients undergoing egg banking, egg donation cycles and fertility preservation before cancer therapy, these findings underscore the importance of capturing every possible oocyte in each IVF cycle.

Data points show the percentage of cases in which a single retrieval cycle resulted in at least one live birth per the number of clinically retrieved oocytes. Dashed lines show the projected impact of one, two or three extra oocytes being added to the patient’s available oocyte pool. Adapted using the data from ref. 41.

In addition to increasing the oocyte yield, gentler and consistent handling of oocytes by automation may also enhance blastocyst utilization and live birth rates. To quantitatively assess the aggregate clinical impact of FIND-Chip technology, randomized controlled trials could be designed either by randomization of patients undergoing IVF retrievals or splitting the FF samples of individual patients between automated and manual screening arms. For both approaches the primary endpoint would be the blastocyst utilization rate; that is, the number of fresh-transferred plus frozen blastocysts per retrieval. Secondary endpoints would include implantation rates per transfer and CLBR per transfer. We estimate that the timeline for an adequately powered study would be approximately 1–2 years to collect the primary objective, up to 2–3 years to collect the CLBR outcomes, similar to some recent trials examining the use of sequential imaging and artificial intelligence to select embryos for transfer19,42.

The FIND-Chip device fully automates the process of oocyte isolation from FF, enabling a nonexpert operator to use the system, which is an important milestone to improve patient access to IVF treatment. Currently, only a fraction of infertility patients have access to IVF care43, and demand will continue to increase because of rising infertility44, delayed childbearing and the expanding use of egg banking for fertility preservation45. It is well recognized that the main obstacles to IVF’s broader adoption are its high costs and accessibility challenges46,47,48,49, which are driven by the need for a complex laboratory and highly trained workforce confining IVF centers to high population areas. The automated closed system, and portable aspect of the FIND-Chip will enable the collection and preparation of eggs unconstrained by the availability of a trained workforce, or the need for an IVF laboratory. Together with other advances in miniaturized automation of vitrification, ICSI and embryo culture, this opens up the possibility of establishing and operating smaller and lower-cost clinics to increase patient access to fertility treatment. For example, egg retrieval and oocyte vitrification could be completed at remote ‘satellite’ clinics operated by larger IVF centers, which would drastically reduce the travel burden for the patient. Vitrified oocytes could be transported and handled at a central IVF laboratory for completion of the IVF procedure. In this scenario, FIND-Chip performing the isolation and denudation steps simultaneously, leaves only the task of freezing of oocytes (and sperm), which could be completed either by an embryologist or an automated vitrification system.

The current FIND-Chip device has a few design features that may limit its use in certain clinics based on current practices. First, the FIND-Chip system delivers denuded oocytes, making it necessary to perform ICSI as the default insemination method. This decision was driven by the fact that despite published data showing no benefit of ICSI in nonmale factor infertility cases50,51, the majority of autologous fresh IVF cycles in North America (USA and Canada) now utilize ICSI (79%)52. Second, oocytes are denuded immediately instead of a ‘wait-time’ after COC removal from FF. Interestingly, this practice seems to have ensued mainly for logistical reasons, as highlighted in a recent study53, which concluded that the optimal insemination time window in ICSI might be wider than previously thought. Even though there are differences among clinical practices in terms of a ‘wait-time’ between the removal of oocytes from FF and denudation, recent findings showed no impact of minimizing this wait-time on ICSI fertilization rates per MII injected, blastocyst rates and live birth rates54. It is also a common practice to denude oocytes in the first hour before vitrification55 and egg banks in the USA recommend immediate denudation after collection in their protocols. Finally, the current design does not indicate when the first oocyte is detected in the FF; oocytes are only confirmed after processing, rather than during the retrieval process. We envision that future iterations of this technology, if required, can enable real-time oocyte identification and compatibility with conventional insemination.

In conclusion, we have developed and validated an automated microfluidic platform that reliably isolates and denudes oocytes from follicular fluid while revealing critical shortcomings in current manual IVF procedures. The FIND-Chip’s consistent ability to recover previously undetected oocytes, which can develop into usable and viable embryos, meaningfully impacts the total reproductive potential of an IVF cycle. This finding also raises important questions about the unrealized clinical benefit of the multitude of oocytes that are routinely discarded using manual IVF techniques. This study demonstrates that optics-free screening via microfluidic automation of the process is not only feasible, but also carries substantial clinical value.

Methods

Ethical compliance

All studies were conducted in full compliance with institutional ethical standards and approved protocol, with oversight from the accredited IRB (WCG, Cary, NC, USA). Details about each IRB decision and how they relate to data figures in the study are provided in the Supplementary Table.

Chip fabrication

Initial design iterations of FIND-Chip devices were fabricated in-house via standard polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) prototyping methods56, and the final design was fabricated via injection molding in cyclic olefin polymer plastic using a commercial partner (Stratec Consumables) (Extended Data Fig. 5). Overall, PDMS and plastic chips were similar in design and functionality, and there were minor differences due to: (1) modifications to device geometry over the course of chip design and development; and (2) as a result of the manufacturing method. PDMS chips are disposable, but not suitable for large-scale clinical use because of limitations in scalable manufacturing. Injection-molded plastic chips are disposable, can be inexpensively fabricated at scale, and are suitable (along with disposable, single-use tubing and reservoirs) for various sterilization methods (for example, E-beam, gamma irradiation). Once the FF is loaded into the system reservoir, the fluidic system is closed, and tissue interacts with only sterilized, disposable components.

Collection and handling of FF

Pre-screened FF samples were collected from local IVF clinics and transferred to our laboratory up to 3 h after the egg retrieval. In the pilot trial, the instrument was located in the clinic, and we processed the FF sample immediately after it became available. Except for the pilot trial in which extra oocytes were used for patients’ treatment, all FF samples were de-identified and did not have any patient-specific information. After transfer to our laboratory, samples were kept in a 37 °C bead bath until the time of processing.

All samples were processed the same day, up to 8 h after retrieval. Two of the participating clinics used an anti-coagulant (heparin) during FF retrieval, while the other two did not. At the time of processing, occasionally blood clots were observed in the pre-screened FF samples. Small blood clots in the sample were trapped by the filter module of the chip during processing, and did not impact the device process. On occasion, a multi-millimeter blood clot was observed in the FF sample, which was not aspirated by the operator. Typically, it took about 1 min of handling time for the operator to aspirate the FF from the pot, load it into the reservoir and start the process. Samples from different patients were never pooled (mixed) and only one patient’s sample was processed at a time. We have not experienced an upper limit to the maximum FF volume that could be processed by a chip, but multiple loads by the operator were required for larger samples because of the maximum volume (55 ml) of the reservoir of the prototype system. We processed the full volume of the discarded FF for only 31.8% (185 of 582) of the patient samples. Several considerations determined whether we opted to fully process a sample, including sample volume, sample age (time between retrieval and process) and number of available samples. Typically, if there were other available samples to run, we processed only 55 ml from a sample to allow us to run FF samples from more patients (albeit without being able to run full volume) to evaluate device performance across a larger patient cohort. Fifty-five milliliters was selected based on the FF reservoir volume of the prototype system. The reservoir volume does not limit the amount of FF that the system can process but requires the user to manually refill the reservoir and adds sample loading time to the process. Overall, in the general patient group, the average discarded FF volume collected was V = 96.3 ml, the average processed FF volume was V = 56.9 ml and the maximum FF volume that was processed was V = 200 ml.

Experimental test setup

Two solutions were used during FF processing with the FIND-Chip: (1) handling media (MHM-C (Fujifilm Irvine Scientific) or GMOPS (VitroLife)) and (2) HYA. The HYA was diluted to a final concentration of 80 IU ml−1 (cat. no. H4272, Sigma-Aldrich) in handling media. Both solutions were warmed to 37 °C in a bead bath and loaded into fluidic reservoirs of the FIND-Chip instrument by the operator. Overall, operator interaction with the instrument was limited to filling the three reservoirs with corresponding fluids (handling media, HYA and FF), which did not cause variability in experimental outcomes. We had failed processes very infrequently. These were due to errors in chip assembly (for example, tubing not properly connected to chip) or the manufacturing process (for example, bad bonding of PDMS to glass), which are expected because of the early prototype stage of the kit and the instrument.

Plastic syringes were used as fluidic reservoirs (Becton Dickinson) and Tygon ND 100-65 tubing (Saint-Gobain) was used to connect the devices to reservoirs, product dish and waste containers. After all reservoirs and tubing were connected to the device, the entire system was primed with handling media to remove any air. In the majority of runs, the device was not placed under a microscope to monitor the process. We utilized the microscope in a subset of runs (mostly in early development stages) for characterization and to acquire images.

Optimization of process parameters for automation

The FIND-Chip was optimized to isolate oocytes with high yield and high purity in a clinically acceptable process time, while ensuring the oocytes retain their viability. Toward this goal, we aimed to isolate the denuded oocytes in the F-Cap section of the capture module, and utilize the C-Cap section to arrest slightly larger, nontarget debris. For this study, bCOCs were used instead of other animal models (for example, mouse), because FIND-Chip functionality is size dependent and bovine oocytes are similar in size to human oocytes. Oocytes’ isolation location across the capture module is determined based on three parameters: (1) filtration cutoff size, (2) oocyte denudation level and effective hydrodynamic size, and (3) fluid flow rate. For example, oocytes move further downstream in the capture module from the C-Cap to F-Cap sections (Extended Data Fig. 2a), either as they are denuded (reducing their effective size) or as the flow rate is increased (increasing the fluidic drag force).

To investigate the effect of the denudation level and fluid flow rate on oocyte isolation locations, a known quantity of bCOCs was spiked (added) in oocyte handling media (MHM-C), the sample was processed using FIND-Chip and the denudation level of the oocytes and their position in the capture module were tracked using a microscope. The optimized process yielded fully denuded oocytes after four denudation cycles (with each cycle composed of ten oscillations over the denuder module), and a narrow distribution of oocytes across the first three rows of the F-Cap section (Extended Data Fig. 2b). In these experiments, we tested three flow rates: 5 ml min−1 (slow), 8 ml min−1 (normal) and 11.5 ml min−1 (fast), and implemented up to six denudation cycles in our process. Expectedly, at a high flow rate, oocytes were fully denuded in fewer denudation cycles. However, they also traveled further in the F-Cap section of the capture module, because of increased fluidic forces acting on the oocytes. Low flow rate did not yield full denudation of oocytes in the number of denudation cycles tested and also had a wider distribution of oocytes across the capture module at the end of the process (Extended Data Fig. 2b). As a result, we decided 8 ml min−1 was optimal for processing oocytes. Under these optimized parameters, the sample processing time using FIND-Chip was approximately 25–30 min, after the sample is fully loaded into the system. Sample loading time scaled linearly with the sample volume and was approximately 5 min for a 50-ml FF sample.

FIND-Chip was tested for recovery of bCOCs spiked into pre-screened human FF samples, to evaluate released product purity and other performance impacts of tissue found in complex human FF. Clinical FF samples were collected from a local IVF center, sourced from patients who had undergone the egg retrieval procedure that morning. Briefly, these FF samples were already manually screened and designated as discard by a trained embryologist after recovering all oocytes that could be identified. In a typical experiment, about 20 bCOCs were spiked in a 50-ml FF sample. In these experiments (n = 10), carry-over tissue debris did not hinder oocyte recovery from the product droplet (Extended Data Fig. 2c) and users were able to locate and remove all the oocytes. Overall, 99.5% (219 of 220) and 98.0% (216 of 220) of the total spiked bovine oocytes were isolated in the capture module and released in a product dish respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2d).

Bovine oocyte preparation, fertilization and blastomere counting

bCOC were purchased from a commercial supplier (Simplot Animal Sciences). The bCOC were shipped overnight in maturation media, and upon arrival, were already in the process window for fertilization (18–22 h post-collection). IVF was performed on all experimental groups as previously described57. Briefly, bCOC and denuded bovine oocytes were washed and maintained in BO-IVF media (IVF Biosciences) at 38.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 5% O2. Simultaneously, freeze–thawed bull semen was first centrifuged at 600g for 15 min, followed by a wash step with SemenPrep media (IVF Biosciences) and another centrifugation at 600g for 10 min. Bull sperm was purchased from a commercial supplier (Simplot Animal Sciences) and different lots were used for experiments. The sperm were added at a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells per ml to the bCOCs and denuded oocytes. After 18 h of incubation, presumptive zygotes were denuded, washed and transferred to BO-IVC media (IVF Biosciences) for further culturing. The embryos were cultured for 8 days post-insemination at 38.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 5% O2.

To determine the number of blastomeres, blastocysts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and stained with Hoechst (Invitrogen). Z-stacked fluorescence images were captured using an EVOS M7000 microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The images were processed and analyzed for blastomere count using ImageJ software. Blastomere counts were performed using blastocysts formed from the fertilization experiments (using embryos from two of the experiment days), and images were taken from a randomly chosen subset of available blastocysts.

Donated oocytes

Patients were consented per an IRB-approved protocol (WCG-IRB #1300130). Consented patients who had more than 20 oocytes found in the clinic donated between 1 and 4 COCs to the study depending on the total number of clinical oocytes (Supplementary Table). Donated oocytes were then placed in a temperature-controlled travel incubator and transferred to our laboratory for processing. In some experiments, donated oocytes were stained with Calcein-AM (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 15 min before spiking into the patient’s pre-screened FF.

Developmental competency of extra oocytes

For this pilot study, patients were consented per an IRB-approved protocol (WCG-IRB #1377160). The automated FIND-Chip instrument was set up in close proximity to the embryology laboratory and was placed in an incubator at 37 °C to provide a temperature-controlled environment during FF processing. All pre-screened FF samples were tracked and witnessed to maintain a strict chain of custody per patient. Once the processing of pre-screened FF was completed, any extra oocytes found were returned within ~45 min to the patient’s allocation of oocytes, maintained separately for the purposes of tracking and maintained in standard embryo culture media until the time of ICSI. All the oocytes recovered by the FIND-Chip device and resulting fertilized embryos were separately identified to distinguish them from the clinically recovered oocytes as deemed by the IRB protocol. The ICSI procedure, embryo culture, blastocyst freezing protocols were conducted per the standard clinical procedures as previously described54,58.

Statistics and reproducibility

All the experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates. For some figures, representative data are shown, but each experiment included a minimum of three biological replicates. Brown–Forsythe and Welch one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons were used in analyzing fertilization and blastomere experiment results to compare all the groups. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and was not rejected (P > 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 10 software and JMP.

No randomization or blinding was used, and no bias was introduced during experiments. The number of bovine oocytes used in fertilization experiments was selected to reflect a high-oocyte scenario in humans. Data size was chosen to provide sufficient repeats to account for biological day-to day variability. Samples were obtained from multiple clinics to minimize potential site-specific bias. Sex and gender were not considered, because this study required only female participants.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

De-identified data that is used to generate all the visuals in this study is provided as source data files in the Harvard Dataverse (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/FINDchip/). Data is accessible to public with no login or approval requirements. Only the data for Fig. 5 is not included in the source data files. The original data in Fig. 5 was previously published by Huttler et al. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2025.07.029)41 and made available by the coauthors of that publication. Clinical data has been de-identified at the time of testing per the national and local laws and HIPAA regulations. In addition, the oocyte retrieval and investigation dates are further de-identified in the available data to avoid any attempt to re-identify the participants in any way.

References

Mascarenhas, M. N. et al. Trends in primary and secondary infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of demographic and reproductive health surveys. Lancet 381, S90 (2013).

Skakkebæk, N. E. et al. Environmental factors in declining human fertility. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 139–157 (2022).

Bhattacharjee, N. V. et al. Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2057–2099 (2024).

Steptoe, P. C. & Edwards, R. G. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet 312, 366 (1978).

Wang, J. & Sauer, M. V. In vitro fertilization (IVF): a review of 3 decades of clinical innovation and technological advancement. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2, 355–364 (2006).

Swain, J. E. et al. Optimizing the culture environment and embryo manipulation to help maintain embryo developmental potential. Fertil. Steril. 105, 571–587 (2016).

Palermo, G., Joris, H., Devroey, P. & Steirteghem, A. C. V. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet 340, 17–18 (1992).

Loutradi, K. E. et al. Cryopreservation of human embryos by vitrification or slow freezing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 90, 186–193 (2008).

Sunkara, S. K. et al. Association between the number of eggs and live birth in IVF treatment: an analysis of 400 135 treatment cycles. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1768–1774 (2011).

Meldrum, D. Quality control, best practices and variability of IVF results. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 24, 95–96 (2020).

Campbell, A. et al. In vitro fertilization and andrology laboratory in 2030: expert visions. Fertil. Steril. 116, 4–12 (2021).

Fanton, M., Cho, J. H., Baker, V. L. & Loewke, K. A higher number of oocytes retrieved is associated with an increase in fertilized oocytes, blastocysts, and cumulative live birth rates. Fertil. Steril. 119, 762–769 (2023).

Kim, H. H. More is better: oocyte number and cumulative live birth rate. Fertil. Steril. 119, 770–771 (2023).

Vaughan, D. A. et al. How many oocytes are optimal to achieve multiple live births with one stimulation cycle? The one-and-done approach. Fertil. Steril. 107, 397–404 (2017).

Mendizabal-Ruiz, G. et al. A digitally controlled, remotely operated ICSI system: case report of the first live birth. Reprod. Biomed. Online 50, 104943 (2025).

Hajek, J. et al. A randomised, multi-center, open trial comparing a semi-automated closed vitrification system with a manual open system in women undergoing IVF. Hum. Reprod. 36, 2101–2110 (2021).

Vasilescu, S. A. et al. A microfluidic approach to rapid sperm recovery from heterogeneous cell suspensions. Sci. Rep. 11, 7917 (2021).

Costa-Borges, N. et al. First babies conceived with Automated Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection. Reprod. Biomed. Online 47, 103237 (2023).

Illingworth, P. J. et al. Deep learning versus manual morphology-based embryo selection in IVF: a randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial. Nat. Med. 30, 3114–3120 (2024).

Chinnasamy, T. et al. Guidance and self-sorting of active swimmers: 3D periodic arrays increase persistence length of human sperm selecting for the fittest. Adv. Sci. 5, 1700531 (2018).

Nosrati, R. et al. Rapid selection of sperm with high DNA integrity. Lab Chip 14, 1142–1150 (2014).

Zaferani, M., Palermo, G. D. & Abbaspourrad, A. Strictures of a microchannel impose fierce competition to select for highly motile sperm. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav2111 (2019).

Zeggari, R., Wacogne, B., Pieralli, C., Roux, C. & Gharbi, T. A full micro-fluidic system for single oocyte manipulation including an optical sensor for cell maturity estimation and fertilisation indication. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 125, 664–671 (2007).

Angione, S. L., Oulhen, N., Brayboy, L. M., Tripathi, A. & Wessel, G. M. Simple perfusion apparatus for manipulation, tracking, and study of oocytes and embryos. Fertil. Steril. 103, 281–290 (2015).

Weng, L. et al. On-chip oocyte denudation from cumulus–oocyte complexes for assisted reproductive therapy. Lab Chip 18, 3892–3902 (2018).

Mokhtare, A. et al. A sound approach for ova denudation. F S Sci. 6, 118–125 (2025).

Ma, R. et al. In vitro fertilization on a single-oocyte positioning system integrated with motile sperm selection and early embryo development. Anal. Chem. 83, 2964–2970 (2011).

Heo, Y. S., Cabrera, L. M., Bormann, C. L., Smith, G. D. & Takayama, S. Real time culture and analysis of embryo metabolism using a microfluidic device with deformation based actuation. Lab Chip 12, 2240–2246 (2012).

Lai, D., Ding, J., Smith, G. W., Smith, G. D. & Takayama, S. Slow and steady cell shrinkage reduces osmotic stress in bovine and murine oocyte and zygote vitrification. Hum. Reprod. 30, 37–45 (2015).

Heo, Y. S. et al. Controlled loading of cryoprotectants (CPAs) to oocyte with linear and complex CPA profiles on a microfluidic platform. Lab Chip 11, 3530–3537 (2011).

Mishra, A. et al. Tumor cell-based liquid biopsy using high-throughput microfluidic enrichment of entire leukapheresis product. Nat. Commun. 16, 32 (2025).

Di Carlo, D. et al. Continuous inertial focusing, ordering, and separation of particles in microchannels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 18892–18897 (2007).

Gardner, D. K., Lane, M., Stevens, J., Schlenker, T. & Schoolcraft, W. B. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil. Steril. 73, 1155–1158 (2000).

The Lancet Global Health. Infertility—why the silence? Lancet Glob. Health 10, e773 (2022).

Ozcan, P. et al. Does the use of microfluidic sperm sorting for the sperm selection improve in vitro fertilization success rates in male factor infertility? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 47, 382–388 (2021).

Barnes, J. et al. A non-invasive artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of human blastocyst ploidy: a retrospective model development and validation study. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e28–e40 (2023).

Eggersmann, T. K. et al. Controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) with follitropin delta results in higher cumulative live birth rates compared with follitropin alfa/beta in a large retrospectively analyzed real-world data set. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 23, 25 (2025).

Wu, L. et al. The first multiple center prospective study of rhFSH CTP in patients undergoing assisted reproductive technology in China. Sci. Rep. 15, 2666 (2025).

Andersen, A. N. et al. Individualized versus conventional ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded, phase 3 noninferiority trial. Fertil. Steril. 107, 387–396 (2017).

Polyzos, N. P. et al. Cumulative live birth rates according to the number of oocytes retrieved after the first ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a multicenter multinational analysis including ∼15,000 women. Fertil. Steril. 110, 661–670 (2018).

Huttler, A. et al. Achieving two live births from one ovarian stimulation cycle: the one-and-done approach revisited. Fertil. Steril. 125, 73–82 (2026).

Kieslinger, D. C. et al. Clinical outcomes of uninterrupted embryo culture with or without time-lapse-based embryo selection versus interrupted standard culture (SelecTIMO): a three-armed, multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 401, 1438–1446 (2023).

Chambers, G. M., Sullivan, E. A., Ishihara, O., Chapman, M. G. & Adamson, G. D. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil. Steril. 91, 2281–2294 (2009).

Fauser, B. C. J. M. et al. Declining global fertility rates and the implications for family planning and family building: an IFFS consensus document based on a narrative review of the literature. Hum. Reprod. Update 30, 153–173 (2024).

Johnston, M., Richings, N. M., Leung, A., Sakkas, D. & Catt, S. A major increase in oocyte cryopreservation cycles in the USA, Australia and New Zealand since 2010 is highlighted by younger women but a need for standardized data collection. Hum. Reprod. 36, 624–635 (2021).

Teoh, P. J. & Maheshwari, A. Low-cost in vitro fertilization: current insights. Int. J. Womens Health 6, 817–827 (2014).

Chambers, G. M. et al. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil. Steril. 101, 191–198 (2014).

Mackay, A., Taylor, S. & Glass, B. Inequity of access: scoping the barriers to assisted reproductive technologies. Pharmacy 11, 17 (2023).

Patrizio, P., Albertini, D. F., Gleicher, N. & Caplan, A. The changing world of IVF: the pros and cons of new business models offering assisted reproductive technologies. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 39, 305–313 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection versus conventional in-vitro fertilisation for couples with infertility with non-severe male factor: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 403, 924–934 (2024).

Patel, K., Vaughan, D. A., Rodday, A. M., Penzias, A. & Sakkas, D. Compared with conventional insemination, intracytoplasmic sperm injection provides no benefit in cases of nonmale factor infertility as evidenced by comparable euploidy rate. Fertil. Steril. 120, 277–286 (2023).

Baker, V. L. et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ICMART): world report for cycles conducted in 2017–2018. Hum. Reprod. 40, 1110–1126 (2025).

Bárcena, P., Rodríguez, M., Obradors, A., Vernaeve, V. & Vassena, R. Should we worry about the clock? Relationship between time to ICSI and reproductive outcomes in cycles with fresh and vitrified oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 31, 1182–1191 (2016).

Esiso, F. M. et al. The effect of rapid and delayed insemination on reproductive outcome in conventional insemination and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in vitro fertilization cycles. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 2697–2706 (2021).

Cornet-Bartolomé, D., Rodriguez, A., García, D., Barragán, M. & Vassena, R. Efficiency and efficacy of vitrification in 35 654 sibling oocytes from donation cycles. Hum. Reprod. 35, 2262–2271 (2020).

Duffy, D. C., McDonald, J. C., Schueller, O. J. A. & Whitesides, G. M. Rapid prototyping of microfluidic systems in poly(dimethylsiloxane). Anal. Chem. 70, 4974–4984 (1998).

Saito, S. et al. Requirement for expression of WW domain containing transcription regulator 1 in bovine trophectoderm development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 555, 140–146 (2021).

Ardestani, G. et al. Effect of time post warming to embryo transfer on human blastocyst metabolism and pregnancy outcome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 41, 1539–1547 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients for their generosity and participation in the clinical studies. We are grateful to the collaborating clinics, physicians, embryologists and staff for their invaluable support throughout the study. This work was partially supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R44HD105529 (E.O.). The funding source was not involved in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.R.M., T.B., M.S., A.S.P., M.M.A., T.L.T., R.K., M.T., D.S. and E.O. contributed to planning the study and designing the research strategy. B.R.M., S.C.C., J.D., N.G., T.B. and E.O. contributed to data acquisition and analysis of the results. B.R.M., T.L.T., R.K., M.T., D.S. and E.O. contributed to interpretation of data. B.R.M., S.C.C., J.D. and N.G. contributed to preparation of the figures and data representation. B.R.M. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. D.S. and E.O. supervised the research. All authors provided substantive contributions to the revisions and approve the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.R.M., S.C.C., J.D., N.G., T.B., M.S., A.S.P., M.M.A., T.L.T., R.K., M.T., D.S. and E.O. hold equity in AutoIVF Inc., and B.R.M., S.C.C., J.D., N.G., T.B., R.K. and E.O. have been employed by AutoIVF Inc., which may benefit from the publication of this research. Certain aspects of the FIND-Chip design and process are protected in patent applications; B.R.M., E.O., S.C.C., M.T., T.L.T., D.S. and R.K. have inventorships on the application PCT/US2024/041298, and B.R.M., E.O., S.C.C., M.T., T.L.T., D.S. and R.K. have inventorships on the application PCT/US2024/041329. These financial interests have been disclosed in accordance with journal policies.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Mina Alikani, Elnur Babayev and Jack Yu Jen Huang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Ashley Castellanos-Jankiewicz, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 FIND-Chip process sequence.

The FIND-Chip process is operated in four steps that combine steady and oscillatory flow regime to guide oocytes between different microfluidic modules. In Step 1 (Sample loading), FF is loaded into the chip using steady flow, allowing tissues and cells to be captured or expelled through the modules. In Step 2 (Hyaluronidase, HYA treatment), captured tissues is exposed to HYA to facilitate dissociation of cumulus tissue and enable subsequent denudation. This differs from manual HYA treatment where only isolated COCs are exposed to the enzyme. HYA treatment is immediately followed by a wash step with media (MHM-C) to replace the HYA solution interacting with the tissue and restricts oocyte contact with HYA to <120 s, consistent with clinical standards. In the first phase of Step 3 (Denudation), oocytes are moved from the Capture module to Denuder module, oscillated through the denudation features, and brought back to the Capture module. In the second phase of Step 3 (Wash), the oocytes and the tissue that accumulate in the Capture module is oscillated within the module with a net positive flow downstream to remove non-target tissue and further enrich the release product. The morphological differences between the layer-like, nonuniform tissue debris versus spherical, uniformly sized oocytes enable this enrichment via oscillatory flow. During these oscillations, oocytes are predictably stopped by posts based on their size, whereas non-target tissue can pass into waste based on their orientation. These denudation-wash cycles are repeated until the oocytes are fully denuded, and the desired product enrichment levels are achieved. The number of denudation and wash cycles are pre-set based on experimental observations during technology optimization studies. In Step 4 (Release), oocytes are released from the Capture module into a petri dish using a steady, reverse flow.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Technology optimization with bovine COCs spiked in media or human FF.

A) In Capture module, oocytes are transferred to the fine capture (F-Cap) from the coarse capture (C-Cap) when they are fully denuded to improve release purity. B) Oocytes’ distribution in Capture module can be adjusted by flowrate and number of denudation cycles. Denudation of oocytes at the optimized flow rate ensures they accumulate at the target rows of the F-Cap (F1-F3) at the end of the process. C) Oocytes are easily recoverable from the low volume release dish which contains minimal tissue contamination of similar size. D) Oocytes (20 to 40 per experiment) spiked in human FF are isolated with high efficiency using FIND-Chip (N = 10 experiments).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Product of a technology optimization experiment with spiked bovine COCs.

Human oocytes are easily distinguishable from bovine oocytes, and were routinely recovered during technology validation experiments using discarded human FF spiked with bovine oocytes.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Patient samples processed for extra oocytes represent a typical IVF patient cohort.

A) Patient’s clinical oocyte count from manual screening, B) Patient age.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Close-up images of FIND-Chip modules.

A) Filter module (last row), B) Denuder module (last row), C) Concentrator module (entrance), D) Capture module (entrance). (Device features have a wall angle of approximately 3° due to fabrication method. Noted dimensions represent the middle of the device height, which is 350 µm. All scale-bars are 200 µm).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mutlu, B.R., Civale, S.C., Diettrich, J. et al. Microfluidic automation improves oocyte recovery from follicular fluid of patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Nat Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-026-04207-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-026-04207-x