Abstract

Simulated single-cell data are essential for designing and evaluating computational methods in the absence of experimental ground truth. Here we present scMultiSim, a comprehensive simulator that generates multimodal single-cell data encompassing gene expression, chromatin accessibility, RNA velocity and spatial cell locations while accounting for the relationships between modalities. Unlike existing tools that focus on limited biological factors, scMultiSim simultaneously models cell identity, gene regulatory networks, cell–cell interactions and chromatin accessibility while incorporating technical noise. Moreover, it allows users to adjust each factor’s effect easily. Here we show that scMultiSim generates data with expected biological effects, and demonstrate its applications by benchmarking a wide range of computational tasks, including multimodal and multi-batch data integration, RNA velocity estimation, gene regulatory network inference and cell–cell interaction inference using spatially resolved gene expression data. Compared to existing simulators, scMultiSim can benchmark a much broader range of existing computational problems and even new potential tasks.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The simulated datasets are available in Zenodo via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13119261 (ref. 55). The seqFISH+ data can be downloaded using the GiottoData R package, or on GitHub via https://github.com/drieslab/spatial-datasets/tree/master/data/2019_seqfish_plus_SScortex/. The original data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE98674. The 10x Multinome data are available at https://www.10xgenomics.com/resources/datasets/pbmc-from-a-healthy-donor-no-cell-sorting-3-k-1-standard-2-0-0/. The MERFISH data can be obtained using the MouseHypothalamusMoffitt2018 method in R package MerfishData, or originally from Dryad via https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.8t8s248 (ref. 38). The ISSAAAC-seq data can be obtained from https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-11264/. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The scMultiSim R package is available at https://github.com/ZhangLabGT/scMultiSim/ and on Zenodo via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14624601 (ref. 56). scMultiSim is also available on Bioconductor via https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/scMultiSim.html. The code for dataset generation and benchmarking is available at https://github.com/ZhangLabGT/scMultiSim_manuscript/ and on Zenodo via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13626212 (ref. 57).

References

Vandereyken, K., Sifrim, A., Thienpont, B. & Voet, T. Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 494–515 (2023).

Cao, J. et al. Joint profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in thousands of single cells. Science 361, 1380–1385 (2018).

Shah, S., Lubeck, E., Zhou, W. & Cai, L. In situ transcription profiling of single cells reveals spatial organization of cells in the mouse hippocampus. Neuron 92, 342–357 (2016).

Eng, C. -H. L. et al. Transcriptome-scale super-resolved imaging in tissues by RNA seqFISH. Nature 568, 235–239 (2019).

Ståhl, P. L. et al. Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science 353, 78–82 (2016).

Rodriques, S. G. et al. Slide-seq: a scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Science 363, 1463–1467 (2019).

Efremova, M. & Teichmann, S. A. Computational methods for single-cell omics across modalities. Nat. Methods 17, 14–17 (2020).

Pratapa, A., Jalihal, A. P., Law, J. N., Bharadwaj, A. & Murali, T. M. Benchmarking algorithms for gene regulatory network inference from single-cell transcriptomic data. Nat. Methods 17, 147–154 (2020).

Badia-I-Mompel, P. et al. Gene regulatory network inference in the era of single-cell multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 24, 739–754 (2023).

Kamimoto, K. et al. Dissecting cell identity via network inference and in silico gene perturbation. Nature 614, 742–751 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Inference of cell type-specific gene regulatory networks on cell lineages from single cell omic datasets. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38637-9 (2023).

Dries, R. et al. Giotto: a toolbox for integrative analysis and visualization of spatial expression data. Genome Biol. 22, 78 (2021).

Shao, X. et al. Knowledge-graph-based cell-cell communication inference for spatially resolved transcriptomic data with SpaTalk. Nat. Commun. 13, 4429 (2022).

Cang, Z. & Nie, Q. Inferring spatial and signaling relationships between cells from single cell transcriptomic data. Nat. Commun. 11, 2084 (2020).

Cang, Z. et al. Screening cell-cell communication in spatial transcriptomics via collective optimal transport. Nat. Methods 20, 218–228 (2023).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

Welch, J. D. et al. Single-cell multi-omic integration compares and contrasts features of brain cell identity. Cell 177, 1873–1887 (2019).

Argelaguet, R., Cuomo, A. S. E., Stegle, O. & Marioni, J. C. Computational principles and challenges in single-cell data integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1202–1215 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Yang, C. & Zhang, X. scDART: integrating unmatched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data and learning cross-modality relationship simultaneously. Genome Biol. 23, 139 (2022).

La Manno, G. et al. RNA velocity of single cells. Nature 560, 494–498 (2018).

Li, C., Virgilio, M., Collins, K. L. & Welch, J. D. Single-cell multi-omic velocity infers dynamic and decoupled gene regulation. in Research in Computational Molecular Biology (ed. I. Pe’er) 297–299 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Zhang, X., Xu, C. & Yosef, N. Simulating multiple faceted variability in single cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 10, 2611 (2019).

Dibaeinia, P. & Sinha, S. SERGIO: A single-cell expression simulator guided by gene regulatory networks. Cell Syst. 11, 252–271 (2020).

Cannoodt, R., Saelens, W., Deconinck, L. & Saeys, Y. Spearheading future omics analyses using dyngen, a multi-modal simulator of single cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 3942 (2021).

Zhang, Z. & Zhang, X. VeloSim: simulating single cell gene-expression and RNA velocity. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.11.426277 (2021).

Tanevski, J., Ramirez Flores, R. O., Gabor, A., Schapiro, D. & Saez-Rodriguez, J. Explainable multiview framework for dissecting spatial relationships from highly multiplexed data. Genome Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02663-5 (2022).

Crowell, H. L., Morillo Leonardo, S. X., Soneson, C. & Robinson, M. D. The shaky foundations of simulating single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 24, 62 (2023).

Navidi, Z., Zhang, L. & Wang, B. simATAC: a single-cell ATAC-seq simulation framework. Genome Biol. 22, 74 (2021).

Li, C., Chen, X., Chen, S., Jiang, R. & Zhang, X. simCAS: an embedding-based method for simulating single-cell chromatin accessibility sequencing data. Bioinformatics https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad453 (2023).

Song, D. et al. scdesign3 generates realistic in silico data for multimodal single-cell and spatial omics. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 247–252 (2023).

Peccoud, J. & Ycart, B. Markovian modeling of gene-product synthesis. Theoret. Pop. Biol. 48, 222–234 (1995).

Dong, K. & Zhang, S. Deciphering spatial domains from spatially resolved transcriptomics with an adaptive graph attention auto-encoder. Nat. Commun. 13, 1739 (2022).

Oh, S., Park, H. & Zhang, X. Hybrid clustering of single-cell gene expression and spatial information via integrated NMF and k-means. Front. Genet. 12, 763263 (2021).

Zhu, J., Shang, L. & Zhou, X. SRTsim: spatial pattern preserving simulations for spatially resolved transcriptomics. Genome Biol. 24, 39 (2023).

Armingol, E., Officer, A., Harismendy, O. & Lewis, N. E. Deciphering cell-cell interactions and communication from gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 71–88 (2021).

Liu, Z., Sun, D. & Wang, C. Evaluation of cell-cell interaction methods by integrating single-cell RNA sequencing data with spatial information. Genome Biol. 23, 218 (2022).

Xu, W. et al. Issaac-seq enables sensitive and flexible multimodal profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in single cells. Nat. Methods 19, 1243–1249 (2022).

Moffitt, J. R. et al. Molecular, spatial, and functional single-cell profiling of the hypothalamic preoptic region. Science 362, eaau5324 (2018).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2023).

Kriebel, A. R. & Welch, J. D. UINMF performs mosaic integration of single-cell multi-omic datasets using nonnegative matrix factorization. Nat. Commun. 13, 780 (2022).

Gong, B., Zhou, Y. & Purdom, E. Cobolt: integrative analysis of multimodal single-cell sequencing data. Genome Biol. 22, 351 (2021).

Luecken, M. D. et al. Benchmarking atlas-level data integration in single-cell genomics. Nat. Methods 19, 41–50 (2022).

Lee, M. Y. Y., Kaestner, K. H. & Li, M. Benchmarking algorithms for joint integration of unpaired and paired single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data. Genome Biol. 24, 244 (2023).

Chan, T. E., Stumpf, M. P. H. & Babtie, A. C. Gene regulatory network inference from single-cell data using multivariate information measures. Cell Syst. 5, 251–267 (2017).

Huynh-Thu, V. A., Irrthum, A., Wehenkel, L. & Geurts, P. Inferring regulatory networks from expression data using tree-based methods. PLoS ONE 5, e12776 (2010).

Moerman, T. et al. GRNBoost2 and arboreto: efficient and scalable inference of gene regulatory networks. Bioinformatics 35, 2159–2161 (2019).

Papili Gao, N., Ud-Dean, S. M. M., Gandrillon, O. & Gunawan, R. SINCERITIES: inferring gene regulatory networks from time-stamped single cell transcriptional expression profiles. Bioinformatics 34, 258–266 (2018).

Kim, S. ppcor: an R package for a fast calculation to semi-partial correlation coefficients. Commun. Stat Appl. Methods 22, 665–674 (2015).

Dimitrov, D. et al. Comparison of methods and resources for cell-cell communication inference from single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Commun. 13, 3224 (2022).

Munsky, B., Neuert, G. & van Oudenaarden, A. Using gene expression noise to understand gene regulation. Science 336, 183–187 (2012).

Kim, J. & Marioni, J. C. Inferring the kinetics of stochastic gene expression from single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Genome Biol. 14, R7 (2013).

Chen, X., Miragaia, R. J., Natarajan, K. N. & Teichmann, S. A. A rapid and robust method for single cell chromatin accessibility profiling. Nat. Commun. 9, 5345 (2018).

Zeisel, A. et al. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 347, 1138–1142 (2015).

Gaublomme, J. T. et al. Single-cell genomics unveils critical regulators of TH17 cell pathogenicity. Cell 163, 1400–1412 (2015).

Li, H. scMultiSim benchmarking datasets. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13119261 (2024).

Li, H. scMultiSim. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14624601 (2025).

Li, H. scMultiSim manuscript repository snapshot. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13626212 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R35GM143070 to H.L., Z.Z. and X.Z.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32322019 to X.C.) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515011662 and 2022B1515120077 to X.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. conceived the idea and X.C. contributed to the design of scMultiSim. H.L., Z.Z. and M.S. implemented the software package. H.L. performed validations and benchmarks. H.L., X.Z. and Z.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Lin Tang, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Additional Illustration of scMultiSim’s model.

(a) The CIF matrix of size ncell × ncif. If the total number of genes is larger than the those in the GRN, the remaining free (‘non-GRN’) genes will have their tf and ligand-GIV sampled from the user-controlled Gaussian distribution. (b) The GIV matrix of size ncif × ngene, transposed for clarity. Its rows match the columns in the CIF matrix, representing the effect (weight) of each gene to those factors. (c) We perform the same simulation for nstep steps, adding one new cell in each step. Spatial interactions in each step are incorporated. (d) A cell (black) and its neighbors (white) in the grid. The cells in grey are not neighbors.

Extended Data Fig. 2 scMultiSim simulates batch effects and unspliced counts with RNA velocity.

(a) The observed RNA counts in dataset MD9a with added technical noise and batch effects. (b) The spliced true counts, unspliced true counts, and the RNA velocity ground truth from dataset V. The velocity vectors point to the directions of differentiation indicated by red arrows, from the tree root to leaves.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Additional results on technical variation with different capture efficiency α and batch effect size Eb.

Data was simulated using the tree in Fig. 2b, with σi = 1, rd = 0.2, 500 genes and 1000 cells. From the same true counts, various technical noise was added for both continuous and discrete cell population. We show the t-SNE visualization of the gene expression under four configurations α = {0.1, 0.02}, Eb = {1, 2}, and the chromatin accessibility for Eb = {1, 2}. In each grey box, the left sub-figure is colored by cell population ground truth, and the right is colored by batches. With a lower capture efficiency α, one can easily observe the deterioration of data quality in both discrete or continuous trajectories. For example, cluster 3 in (e) is separated from cluster 4 and 5, while in (f) clusters 3, 4 and 5 cannot be differentiated in the visualization; clusters in (a) also have clearer boundaries than (b). The effect of batch effect Eb is also visible in the visualization, where batches are more separated when Eb= 2 in (c,d,g,h). Same observation also applies to the scATAC-seq data.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Additional results on spatial data simulation by scMultiSim.

(a) scMultiSim provides options to control the the cell layout. We show the results of 1200 cells using same-type probability pn = 1.0 and 0.8, respectively. When pn = 1.0, same-type cells tend to cluster together, while pn = 0.8 introduces more randomness. (b) Demonstration of different spatial layouts provided by scMultiSim. Left: the ‘layers’ layout and five cell types. Right: the ‘islands’ layout and four cell types, while specifying cell type 1 and 2 to be ‘islands’. Both datasets were simulated with 1000 cells. (c) Left to right: cells colored by cell types; cells colored by ground truth spatial domains; cells colored by detected spatial domains by STAGATE; cells colored by detected spatial domains by scHybridNMF. (d) Spatially variable genes generated by scMultiSim (from the same dataset with spatial domains) and SRTsim (relative gene expression from its Shiny application). (e) Long-distance CCI with different σrad for the Gaussian kernel. Left: σrad = 1, right: σrad = 5. With a larger σrad, more long-distance CCI are sampled.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Additional results on generated simulated datasets that resemble real datasets.

For all box/violin plots, centers=medians, boxes=Q1-Q3, whiskers= ± 1.5 IQR. We show the statistical properties of both modalities, scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq, for multi-omics datasets (10x Multiome and ISSAAC-seq). For the MERFISH and SeqFISH+ spatial dataset, we show only the RNA modality as it does not have the scATAC-seq data. For SeqFISH+, n= 523 for cells, n= 200 for genes, n= 3000 for ATAC. For MERFISH, n= 3000 for cells, n= 2000 for genes. For ISSAAC-seq, n= 3000 for cells, n= 1000 for genes, n= 3000 for ATAC.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Additional results on benchmarking multimodal GRN inference methods.

N=144. For all box/violin plots, centers=medians, boxes=Q1-Q3, whiskers= ± 1.5 IQR. (a) The results on the main dataset (Fig. 5a), with a uniform y axis. (b) Comparison of CellOracle and scMTNI on the main datasets with different noise levels.

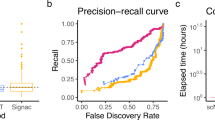

Extended Data Fig. 7 Additional results on CCI benchmarking, including SpaTalk.

For all box/violin plots, centers=medians, boxes=Q1-Q3, whiskers= ± 1.5 IQR. (a) The GRN and CCI network used in datasets C. (b) Additional results of benchmarking Giotto, SpaOTsc, and SpaTalk on dataset C (Fig. 6b). First row: ROC curves of Giotto, SpaOT and SpaTalk. Second row: PRC curves of Giotto, SpaOT and SpaTalk.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Additional results on benchmarking CCI inference methods.

For all box/violin plots, centers=medians, boxes=Q1-Q3, whiskers= ± 1.5 IQR. (a) Results on the main dataset (Fig. 6a) for each cell population type with the ROC curves (n= 48). Each curve in the ROC plots corresponds to one dataset. (b) Results of benchmarking single-cell CCI inference (Fig. 6c) with ROC curves (n= 8). Each curve in the ROC plots corresponds to one dataset.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes A–K, Discussion, Tables 1–3 and Figs. 1–8.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 2–6 and Extended Data Figs 5, 6 and 8

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Zhang, Z., Squires, M. et al. scMultiSim: simulation of single-cell multi-omics and spatial data guided by gene regulatory networks and cell–cell interactions. Nat Methods 22, 982–993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02651-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02651-0

This article is cited by

-

sCCIgen: a high-fidelity spatially resolved transcriptomics data simulator for cell–cell interaction studies

Genome Biology (2025)

-

Single-cell multi-omics in biliary tract cancers: decoding heterogeneity, microenvironment, and treatment strategies

Molecular Biomedicine (2025)

-

Facilitate integrated analysis of single cell multiomic data by binarizing gene expression values

Nature Communications (2025)