Abstract

Drinking behavior is not only homeostatically regulated but also rapidly adjusted before any changes in blood osmolality occur, known as anticipatory thirst satiation. Homeostatic and anticipatory signals converge in the subfornical organ (SFO); however, the neural pathways conveying peripheral information to the SFO before changes in blood composition are incompletely understood. Here we reveal an inhibitory pathway from the medial septum (MS) to the SFO that is involved in the control of anticipatory drinking behavior in mice. MS γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic neurons encode water-satiation signals by integrating cues from the oral cavity and tracking gastrointestinal signals. These neurons receive inputs from the parabrachial nucleus and relay to SFOCaMKII neurons, forming a bottom-up pathway with activity that prevents overhydration. Disruption of this circuit leads to excessive water intake and hyponatremia. Our findings reveal a septal pathway that integrates multiple layers of presystemic signals to fine-tune drinking behavior.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

RNA sequencing data used in this study are available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Sequence Read Archive (accession no. PRJNA1287294). Source data are provided with this paper. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The codes used in this study can be accessed at: https://github.com/Fred-Huangchenyuan/A-bottom-up-septal-inhibitory-circuit-mediates-anticipatory-control-of-drinking.

References

Fitzsimons, J. T. Angiotensin, thirst, and sodium appetite. Physiol. Rev. 78, 583–686 (1998).

McKinley, M. J. et al. The sensory circumventricular organs of the mammalian brain. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 172, 1–122 (2003).

Oka, Y., Ye, M. & Zuker, C. S. Thirst driving and suppressing signals encoded by distinct neural populations in the brain. Nature 520, 349–352 (2015).

Zimmerman, C. A., Leib, D. E. & Knight, Z. A. Neural circuits underlying thirst and fluid homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 459–469 (2017).

Augustine, V. et al. Hierarchical neural architecture underlying thirst regulation. Nature 555, 204–209 (2018).

Augustine, V., Lee, S. & Oka, Y. Neural control and modulation of thirst, sodium appetite, and hunger. Cell 180, 25–32 (2020).

Lowell, B. B. New neuroscience of homeostasis and drives for food, water, and salt. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 459–471 (2019).

Wallace Lind, R., Thunhorst, R. L. & Johnson, A. K. The subfornical organ and the integration of multiple factors in thirst. Physiol. Behav. 32, 69–74 (1984).

McKinley, M. J. & Johnson, A. K. The physiological regulation of thirst and fluid intake. News Physiol. Sci. 19, 1–6 (2004).

Bourque, C. W. Central mechanisms of osmosensation and systemic osmoregulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 519–531 (2008).

Stricker, E. M. & Hoffmann, M. L. Presystemic signals in the control of thirst, salt appetite, and vasopressin secretion. Physiol. Behav. 91, 404–412 (2007).

Fitzsimons, T. J. & Le Magnen, J. Eating as a regulatory control of drinking in the rat. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 67, 273–283 (1969).

Zimmerman, C. A. et al. Thirst neurons anticipate the homeostatic consequences of eating and drinking. Nature 537, 680–684 (2016).

Pool, A. H. et al. The cellular basis of distinct thirst modalities. Nature 588, 112–117 (2020).

Nakamura-Utsunomiya, A., Hiyama, T. Y., Okada, S., Noda, M. & Kobayashi, M. Characteristic clinical features of adipsic hypernatremia patients with subfornical organ-targeting antibody. Clin. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 26, 197–205 (2017).

Allen, W. E. et al. Thirst-associated preoptic neurons encode an aversive motivational drive. Science 357, 1149–1155 (2017).

Harvey, J. A. & Hunt, H. F. Effect of septal lesions on thirst in the rat as indicated by water consumption and operant responding for water reward. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 59, 49–56 (1965).

Blass, E. M. & Hanson, D. G. Primary hyperdipsia in the rat following septal lesions. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 70, 87–93 (1970).

Saad, W. A., de Arruda Camargo, L. A., Antunes-Rodrigues, J. & Simões, S. Effect of electrolytic and chemical lesion by ibotenic acid of the septal area on water and salt intake. Brain Res. Bull. 47, 163–169 (1998).

Andersson, B., Leksell, L. G. & Lishajko, F. Perturbations in fluid balance induced by medially placed forebrain lesions. Brain Res. 99, 261–275 (1975).

Vanderweele, D. A., Davison-Barb, S. & Abelson, R. M. Septal lesions and hyperdipsia in the Mongolian gerbil. Physiol. Behav. 22, 223–227 (1979).

Smardencas, A., Denton, D. A. & McKinley, M. J. Hyperdipsia in sheep bearing lesions in the medial septal nucleus. Brain Res. 1752, 147223 (2021).

Yao, Z. et al. A high-resolution transcriptomic and spatial atlas of cell types in the whole mouse brain. Nature 624, 317–332 (2023).

Saleem, M. et al. Sox6 as a new modulator of renin expression in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. 312, F285–F297 (2020).

N, E. & Hull, C. L. Principles of behavior. An introduction to behavior theory. J. Philos. 40, 558 (1943).

Tsai, N. Y. et al. Trans-Seq maps a selective mammalian retinotectal synapse instructed by nephronectin. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 659–674 (2022).

Matsuda, T., Hiyama, T. Y., Kobayashi, K., Kobayashi, K. & Noda, M. Distinct CCK-positive SFO neurons are involved in persistent or transient suppression of water intake. Nat. Commun. 11, 5692 (2020).

el Ghissassi, M., Thornton, S. N. & Nicolaidis, S. Angiotensin II-induced thirst, but not sodium appetite, via AT1 receptors in organum cavum prelamina terminalis. Am. J. Physiol. 268, R1401–R1405 (1995).

Lenkei, Z., Corvol, P. & Llorens-Cortes, C. The angiotensin receptor subtype AT1A predominates in rat forebrain areas involved in blood pressure, body fluid homeostasis and neuroendocrine control. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 30, 53–60 (1995).

Matsuda, T. et al. Distinct neural mechanisms for the control of thirst and salt appetite in the subfornical organ. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 230–241 (2017).

Klapoetke, N. C. et al. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat. Methods 11, 338–346 (2014).

Yamamoto, M. et al. Reversible suppression of glutamatergic neurotransmission of cerebellar granule cells in vivo by genetically manipulated expression of tetanus neurotoxin light chain. J. Neurosci. 23, 6759–6767 (2003).

Ly, T. et al. Sequential appetite suppression by oral and visceral feedback to the brainstem. Nature 624, 130–137 (2023).

Shen, L. et al. A bottom-up reward pathway mediated by somatostatin neurons in the medial septum complex underlying appetitive learning. Nat. Commun. 13, 1194 (2022).

Menani, J. V., De Luca, L. A. & Johnson, A. K. Role of the lateral parabrachial nucleus in the control of sodium appetite. Am. J. Physiol. 306, R201–R210 (2014).

Kim, D. Y. et al. A neural circuit mechanism for mechanosensory feedback control of ingestion. Nature 580, 376–380 (2020).

Ryan, P. J., Ross, S. I., Campos, C. A., Derkach, V. A. & Palmiter, R. D. Oxytocin-receptor-expressing neurons in the parabrachial nucleus regulate fluid intake. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1722–1733 (2017).

Adrogué, H. J. & Madias, N. E. The challenge of hyponatremia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 1140–1148 (2012).

Hoorn, E. J. & Zietse, R. Diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia: compilation of the guidelines. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1340–1349 (2017).

Augustine, V. et al. Temporally and spatially distinct thirst satiation signals. Neuron 103, 242–249 (2019).

Palmiter, R. D. The parabrachial nucleus: CGRP neurons function as a general alarm. Trends Neurosci. 41, 280–293 (2018).

Karthik, S. et al. Molecular ontology of the parabrachial nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 530, 1658–1699 (2022).

Chiang, M. C. et al. Parabrachial complex: a hub for pain and aversion. J. Neurosci. 39, 8225–8230 (2019).

Scott, T. R. & Small, D. M. The role of the parabrachial nucleus in taste processing and feeding. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1170, 372–377 (2009).

Wickersham, I. R., Finke, S., Conzelmann, K.-K. & Callaway, E. M. Retrograde neuronal tracing with a deletion-mutant rabies virus. Nat. Methods 4, 47–49 (2007).

Wang, H. et al. Parallel gut-to-brain pathways orchestrate feeding behaviors. Nat. Neurosci. 28, 320–335 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. An H2R-dependent medial septum histaminergic circuit mediates feeding behavior. Curr. Biol. 32, 1937–1948 (2022).

Lin, W. et al. Whole-brain mapping of histaminergic projections in mouse brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2216231120 (2023).

Pachitariu, M. et al. Suite2p: beyond 10,000 neurons with standard two-photon microscopy. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/061507 (2016).

Nichterwitz, S. et al. Laser capture microscopy coupled with Smart-seq2 for precise spatial transcriptomic profiling. Nat. Commun. 7, 12139 (2016).

Liao, J. et al. De novo analysis of bulk RNA-seq data at spatially resolved single-cell resolution. Nat. Commun. 13, 6498 (2022).

Picelli, S. et al. Full-length RNA-seq from single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat. Protoc. 9, 171–181 (2014).

Picelli, S. et al. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat. Methods 10, 1096–1100 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Wang for helpful discussions and X. Tong for assistance with customized code development. Cartoons in all figures were created using BioRender.com (agreement no. KH28H4TLPT). This study was supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2021ZD0202803 to Z.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. U23A20533 to Y.W., U21A20418 to Z.C. and 32400841 to L.X.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. 2023M743143 to L.X.) and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. GZC20232370 to L.X.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C., L.X. and Y.W. conceived the project and designed experiments. L.X., Y.S., Y.Z., M.L. and Z.C. led and performed experiments. Y.Z., M.L., Q.Z, and J.L. conducted RNA sequencing experiments and data analysis. X.Q. performed patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments. L.X., Y.S., J.C., X.M., Q.S. and C.G. analyzed and interpreted other experimental data. C.H. performed modeling and computational analysis. L.X. and Y.W. wrote the paper with input from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks Charles Bourque and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Major inputs to the SFO.

a, Schematic of viral injection for identification the upstream inputs to the SFO (n = 3 mice). b, Representative images showing SFO local injection site and retrograde labelled neurons in the TS, triangular septal nucleus; MnPo, median preoptic nucleus; OVLT, MPA, MS/LS, Arc and MnR. Scale bars, 200 µm in the upper panel, 100 µm in the lower right panel. MnPO, OVLT, organum vasculosum laminae terminalis; MPA, medial preoptic area; MS, medial septum; LS, lateral septum, Arc, arcuate hypothalamic nucleus; MnR, median raphe nucleus.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Distinct MS subpopulations are activated during dehydration and satiation.

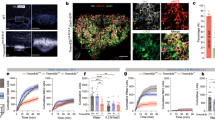

a, Timeline for dual labeling of dehydration-activated (FosTrap) and satiation-activated (c-Fos) neurons in Fos-CreERT2 mice. b, Representative MS histology showing dehydration-activated (red), satiation-activated (green), and overlapping neurons (n = 5 mice). Scale bar, Scale bars, 200 µm in the MS, 50 µm for the magnified images. c, Quantification of overlap across satiation-activated and dehydration-activated neurons. d-e, Dehydration-responded (d) and rehydration-responded (e) neuronal populations project to the SFO but not the MnPO (n = 5 mice). Scale bars, 200 μm in the MS and MnPO, 100 μm in the SFO.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Distinct GABAergic subpopulations in the MS and MnPO.

a, Schematic representation of the experimental design to determine whether MnPO and MS GABAergic neurons are the same GLP1r+ population. b, Representative images showing the GABAergic neurons (green) co-labelled with GLP1r (red) in the MS and MnPO. Scale bars, 200 µm, 50 µm. c, Quantification of the overlap between vGAT and GLP1r signals in the MS and MnPO (n = 6 mice). d, Schematic of viral injection to label the SFO-projecting GABAergic neurons in the MS and MnPO for floresence-guided microdissection. e, Schematics of Smart-seq2 coupled with LCM (Spatial-seq) for analysis of the MS and MnPO GABAergic neurons. f, Volcano plot showing the differentially expressed genes of MSvGAT relative to MnPOvGAT neuronal subpopulation (n = 4 mice). Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided tests. Genes with p-value < 0.05 and log2 fold change > 1 were considered significantly different. g, Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes between the SFO-projecting MSvGAT and MnPOvGAT neuron populations (n = 4 mice). h, Schematic of viral injection to label the SFO-projecting GABAergic neurons in the MS and MnPO for IHC validation. i, Representative images showing that the majority of mCherry+ neurons (red) in the MS, but not in the MnPO, are Sox6+. Scale bars, 200 µm, 50 µm. j, Quantification of the overlap between mCherry and Sox6 signals in the MS and MnPO (n = 3 mice). Data are mean ± SEM ****P < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 4 MSvGAT-SFO circuit does not respond to grooming behavior.

a, Schematic experimental setup. b, Peri-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) of MSvGAT-SFO circuit average responses to grooming behavior. c, Quantification of AUC ΔF/F0 during the ‘pre’ (2 s prior to grooming) and ‘post’ (5 s after the grooming onset) sessions (n = 5 mice). Data are mean ± SEM ns, non-significant (P > 0.9999) Pre versus Post using two-tailed paired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The MSvGAT neurons respond to post-ingestion rehydration.

a, Schematic of i.g. infusion of different solutions. b, Quantification of the total Fos positive numbers in the MS with different test solutions (n = 3 mice for the sham group, n = 4 mice for the saline group, n = 3 mice for the ddH2O group). Data are mean ± SEM. c, Quantification of the overlap between vGLUT2, vGAT and Fos signals with different test solutions (n = 3 mice for the sham group, n = 4 mice for the saline group, n = 3 mice for the ddH2O group). Data are mean ± SEM **P = 0.0090 for (Fos+ & vGAT+) % in ddH2O group versus sham group using ordinary two-way ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparisons test. d, Representative in situ hybridization (FISH) images showing Fos (red) expression pattern co-labelled with vGAT (green) and vGLUT2 (magenta) in the MS. White arrows indicate Fos+ neurons co-labelled with vGLUT2 (magenta), grey arrows indicate Fos+ neurons co-labelled with vGAT (green), while open arrows indicate Fos+ neurons. Scale bars, 200 µm in the MS, 50 µm for the magnified images. Data are mean ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 6 MSvGAT neurons integrate oropharyngeal and gut signals.

a, Schematic of the experimental setup during water intake in free-moving mice (lower) and representative field of view with circles indicating ROIs (upper). b, Heatmap of deconvolved activity rate from individual MSvGAT neurons aligned to licking onset. c, Classification of neuronal responses during drinking. Neurons were categorized as inhibited, activated, or unresponsive using a log-transformed response index. Pie chart shows the proportion of neurons across these categories. d, PSTH showing the average responses from individual MSvGAT neurons to lick onset, comparing drinking-inhibited group (blue traces) versus drinking-unresponsive group (grey traces). Data are mean ± SEM. e, Schematic illustration of intraoral infusion experimental setup. f, Heatmap showing deconvolved activity rate from individual MSvGAT neurons in response to different I.O. infusion rates (upper) and representative traces showing different single neuron responses to corresponding I.O. infusion rates (bottom). g. Classification of neuronal responses to different I.O. infusion rates. Neurons were categorized as inhibited, activated, or unresponsive using a log-transformed response index. Pie charts show the proportion of neurons across these categories for each infusion rate. h, Schematic illustration of intragastric infusion experimental setup. Representative photographs of the stomach before and after I.G. infusion (1 mL). Scale bar, 1 cm. i, Heatmap showing normalized activity from individual MSvGAT neurons in response to I.G. infusion. j-k, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with k-means clustering of individual MSvGAT neurons based on their normalized activity during I.G. infusion (j) and average activity traces for each identified cluster corresponding to I.G. infusion (k).

Extended Data Fig. 7 The MSvGAT-SFO circuit regulates drinking behavior independently of the MnPO.

a, Schematic of viral injection for loss-of-function of MnPOGLP1r neurons with representative histology images for oChIEF-mediated drinking suppression in water-restrained mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. b, Silencing MnPOGLP1r neurons does not affect MSvGAT-SFO-mediated drinking suppression during OFF-ON-OFF photostimulation. Black lines, licks. c, Quantification of total licks during OFF-ON-OFF cycles (n = 6 mice). Data are mean ± SEM **P = 0.0020 for the Pre versus Stim. and *P = 0.0191 for the Pre versus Post, using RM one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

Extended Data Fig. 8 MSvGAT neurons do not project to MnPO.

a, Schematic of anterograde, monosynaptic tracing using Cre-dependent mWGA-mCherry virus targeting the MS. b, Representative images of the mWGA injection site in the MS and anterograde monosynaptic labeling in the SFO and the MnPO. Robust projections are observed in the SFO, but not in the MnPO (n = 3 mice). c, Schematic of Cre-dependent ArchT-GFP virus injection into the MS. d, Representative images of the ArchT-labeled fibers in the MS, SFO and MnPO. Dense fiber projections are apparent in the SFO, while no fiber projections are observed in the MnPO (n = 3 mice). Scale bars, 200 μm in the MS and MnPO, 100 μm in the SFO.

Extended Data Fig. 9 MSvGAT neurons innervate both AT1R-positive and CCK-positive subpopulations of SFOCaMKII neurons.

a, Schematic of rabies retrograde tracing in vGAT-Cre mice. b, Representative images showing starter cells in the SFO and retrograde labelled cells in the MS, co-labelled with GAD1 (red) and vGLUT2 (magenta). Filled arrows indicate RV labelled neurons (green) in the MS. Scale bars, 100 µm in the SFO, 200 µm in the MS, 50 µm for the magnified images. c, Quantification of the overlap between vGLUT2, GAD1 and RV labelled neurons in the MS (n = 3 mice). d, Schematic of viral injection, fiber placement and representative histology images for ChrimsonR-mediated fiber photometry recording. Scale bars, 100 µm in the SFO, 200 µm in the MS. e, Heatmap of individual animal responses to the photostimulation (n = 3 mice). f, PSTH showing the average responses of SFOvGAT neurons to MSvGAT stimulation (n = 3 mice). g, Quantification of AUC ΔF/F0 for the 470 nm recording versus 410 nm recording (n = 3 mice). ns, non-significant (P = 0.5416) for the 470 nm recording versus 410 nm recording using two-tailed paired t-test. h, Schematic of anterograde trace for identification the downstream cell types of the MSvGAT neurons. i, Representative image (left) and quantifications (right) of the viral specificity in the MS (n = 3 mice). Scale bar, 200 µm in the MS, 100 µm for the magnified images. Data are mean ± SEM. j, Left, representative image showing the anterograde labelled neurons (red) co-labelled with CCK (green) and CaMKII (grey) in the SFO. Scale bars, 200 µm in the SFO, 100 µm for the magnified images; Right, quantification of the anterograde labelled neurons (red) co-labelled with CCK (green) and CaMKII (grey) in the SFO (n = 3 mice). Data are mean ± SEM. k, Schematic of anterograde viral tracing combined with immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining to identify the target cell types innervated by MSvGAT neurons in the SFO. l, Representative image showing anterogradely labeled neurons (red) co-labeled with AT1R (green) and CCK (cyan) in the SFO. Scale bars, 100 µm in the SFO, 20 µm for magnified images. m, Quantification of anterogradely labeled neurons (red) co-labeled with AT1R (green) and CCK (cyan) in the SFO (n = 6 mice). Data are mean ± SEM. n, Left, Schematic of viral injection, fiber placement and representative images histology in water-restrained mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. o, Example trace (upper) and heatmaps (lower) of calcium signals upon lick (n = 3 mice). p, Quantification of AUC Zscore during the pre and post sessions (n = 3 mice, 3 trials for each mouse). ***P = 0.0070 for Pre versus Post using two-tailed paired t-test. Data are mean ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 10 The input mapping to the MSvGAT neurons.

a, Schematic of viral injection to identification monosynaptic inputs to MSvGAT neurons (left) and representative image showing starter cells in the MS (right). Scale bars, 200 µm. b, Schematic of strategy for retrograde tracing using rabies virus. c, Representative images showing monosynaptically connected neurons in the SFO, paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH), Hippocampus, the supramammillary nucleus (SuM), the hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray (PAG) and the parabrachial nucleus (n = 3 mice). Scale bars, 200 µm. d, Schematic of viral injection to identification monosynaptic inputs to SFO-projecting MSvGAT neurons using rabies virus strategy. e, Representative images showing no RV signals detected in the PVH, hippocampus, SuM, or PAG (n = 3 mice). Scale bars, 200 μm.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video 1

The video shows calcium activity of a single GABAergic neuron in the MS during water drinking. The neuron was retrogradely labeled from the SFO in VGAT-Cre mice using AAV2/2-RETRO PLUS-DIO-GCAMP6S.

Supplementary Video 2

The video shows mice’s drinking behavior during optogenetic activation of the MS-SFO GABAergic pathway.

Supplementary Table 1

Statistical methods and results.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–6 and Extended Data Figs. 1–10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Sun, Y., Huang, C. et al. A bottom-up septal inhibitory circuit mediates anticipatory control of drinking. Nat Neurosci 28, 2273–2284 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02056-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02056-4

This article is cited by

-

Putting the Brakes on Thirst: A Neural Circuit for Anticipatory Fluid Control

Neuroscience Bulletin (2026)