Abstract

Motor neuron hyperexcitability is a broadly observed yet poorly understood feature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic aggregation of the RNA splicing protein TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) are observed in most ALS and FTD patients. Here we show that TDP-43 dysfunction causes mis-splicing of KCNQ2, which encodes a voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv7.2) that regulates neuronal excitability. Using iPSC-derived neurons and postmortem ALS/FTD brain and spinal cord tissue we find widespread, disease-specific and TDP-43-specific skipping of an exon encoding the KCNQ2 pore domain. The mis-spliced mRNA escapes degradation and is translated into a nonfunctional protein with severely reduced ion conductance that aggregates in the endoplasmic reticulum and causes intrinsic hyperexcitability in ALS neuronal models. This event, which correlates with higher phosphorylated TDP-43 levels and earlier age of disease onset in patients, can be rescued by splice-modulating antisense oligonucleotides that dampen hyperexcitability in induced pluripotent stem cell cortical neurons and spinal motor neurons with TDP-43 depletion. Our work reveals that nuclear TDP-43 maintains the fidelity of KCNQ2 expression and function and provides a mechanistic link between established excitability disruption in ALS/FTD patients and TDP-43 dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

ALS is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder that eliminates motor neurons (MNs) responsible for skeletal muscle contraction and locomotion1. Although the disease is inherited in approximately 10% of cases, most patients are diagnosed with sporadic disease2. Consequently, there remain significant challenges in identifying molecular biomarkers for early diagnosis and therapeutic targets for precision medicine. Nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic aggregation of TDP-43 represents a shared histopathological feature that is found in more than 95% of all ALS cases3. Cytoplasmic aggregation of TDP-43 also occurs in approximately half of patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD-TDP), a disease that shares genetic and clinical features with ALS1,3. TDP-43 pathology is also seen in a considerable proportion (~57%) of patients with Alzheimer’s disease4,5. TDP-43 is a nuclear RNA-binding protein with conserved roles across the RNA lifecycle, from transcriptional regulation to RNA splicing modulation, RNA transport and stability6. The direct link between TDP-43 pathology and neurodegeneration is additionally underscored by the identification of rare mutations in TARDBP, the gene that encodes TDP-43, in ALS and FTD families7,8. However, the cellular mechanisms that relate TDP-43 to neuronal dysfunction and neurotoxicity remain unclear. The recent interrogation of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS cell)-derived neurons with loss of TDP-43 function and postmortem tissue from patients with ALS has revealed hundreds of target mRNAs that undergo mis-splicing9,10,11,12,13. For example, in neurons depleted of TDP-43, the pre-mRNA encoding stathmin 2 (STMN2), a modulator of microtubule stability that impacts axonal outgrowth, yields a truncated variant through activation of a cryptic premature last exon11,12,13. Similarly, TDP-43 depletion leads to the inclusion of a cryptic exon in UNC13A9,10, which encodes a protein with critical functions in synaptic vesicle release14, resulting in nonsense-mediated decay and downregulation of the protein. Intriguingly, polymorphisms in UNC13A that overlap with TDP-43 binding sites are strongly associated with increased ALS and FTD risk15. These findings have shifted the focus from gain-of-function effects associated with aggregated TDP-43 to loss-of-function effects driven by its nuclear depletion, as they underscore direct relationships between TDP-43 pathology, neuronal function and disease risk. However, a link between the role of TDP-43 in splicing and commonly observed clinical features of ALS/FTD has yet to be established.

Neuronal hyperexcitability is a broadly observed clinical feature in familial and sporadic ALS16,17,18,19 and FTD20,21,22. MN excitability, measured by transcranial magnetic stimulation and threshold tracking nerve conduction studies, is an early indicator of MN disease16,17,18,19, and greater excitability is prognostic of faster disease progression and worse survival23,24. Excitability disturbances have been linked to a loss of cortical inhibition25,26, noradrenaline reduction27 and changes in the expression and activity of key ion channels that serve to regulate intrinsic membrane potential28,29,30. Hyperexcitability has been observed in murine TDP-43 models31,32 and iPS cell-based ALS models and can be modulated by the anti-seizure medication retigabine29,33,34 (also known as ezogabine), an activator of Kv7 channels, which are known to be widely expressed in the nervous system and have a central role in regulating excitability35,36. Treatment of ALS iPS cell MNs with ezogabine reduced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and improved survival, suggesting a mechanistic interaction between excitability and proteotoxic degeneration33,34. Activation of Kv7 channels has also been shown to improve neuromuscular function and survival of MNs in ALS mouse models37. Notably, retigabine was proven to be effective at decreasing both cortical and spinal MN excitability in individuals with ALS in a phase 2 clinical trial38. Despite its wide prevalence in the patient population and its therapeutic potential, the mechanisms that drive neuronal hyperexcitability in ALS are poorly understood.

Here, we sought to examine a potential association between TDP-43 dysfunction and neurophysiology. By integrating gene expression datasets from human iPS cell-derived neurons depleted of TDP-43 and postmortem ALS/FTD tissue, we identify spurious skipping of exon 5 of the voltage-gated potassium channel gene KCNQ2 (KCNQ2∆E5). KCNQ2 encoded protein (Kv7.2) forms heterotetrameric channels with other Kv7 subunits to conduct M-current and regulate repetitive firing and excitability in neurons39. We show that KCNQ2 splicing is sensitive to TDP-43 levels, and aberrant pre-mRNA processing yields a non-functional protein that disrupts neuronal excitability, accumulates within the ER of iPS cell-derived neurons and forms ubiquitin-positive accumulations in postmortem spinal cord tissue from patients with ALS. Critically, we demonstrate that splice-modulating antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) that restore KCNQ2 splicing can rescue hyperexcitability in iPS cell cortical and spinal neurons with TDP-43 depletion. Collectively, our findings highlight KCNQ2∆E5 as a reliable molecular biomarker of TDP-43 dysfunction and provide a direct connection between TDP-43 pathology and intrinsic neuronal hyperexcitability in ALS/FTD.

Results

Spinal iPS cell MNs exhibit several TDP-43-dependent splicing events

We previously reported gene expression differences in purified Hb9–GFP positive human MNs derived from iPS cells depleted of TDP-43 (ref. 11). Here, we analyzed these RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets using the MAJIQ pipeline40 and identified a stringent set of 125 differential splicing variants, statistically supported by differential splicing of at least 10% (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Classification of variants revealed that most TDP-43 sensitive events include cassette exons; that is, splicing events involving exon inclusion or skipping (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). We discovered 11 unique and statistically significant de novo processing events that are neither detected in control-treated neurons nor defined within current gene annotations, including previously reported premature termination events in STMN2 and ARHGAP32, cryptic exon inclusions in KALRN and others9,10,11,12 (Fig. 1a). Among these, we identified a spurious exon skipping event in the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ2 (Fig. 1a). We asked whether the splice junctions we identified in purified spinal MNs were prevalent across other datasets of TDP-43 dysfunction reported in iPS cell-derived cortical neurons9 and neuronal nuclei from postmortem brains of patients with ALS/FTD41. Despite using different criteria for defining differential splicing, we observed significant overlap, with 87 out of 125 of MN events also perturbed in at least one of the other datasets (Extended Data Fig. 1c). This was restricted to not only annotated alternative splicing events, but also de novo or derepressed cryptic splicing events (Extended Data Fig. 1c). These analyses add further clarity to TDP-43-regulated processes in neurons and provide a framework to investigate the mechanistic interaction between TDP-43 loss-of-function and disease processes.

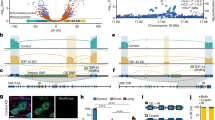

a, Differential splicing analysis of stem cell-derived MNs treated with TDP-43 (n = 6) or scrambled (n = 6) siRNAs reported previously11. Annotated alternative splicing events are shown in green, de novo events are shown in orange and a de novo KCNQ2 event is shown in red. b, Mis-spliced genes after TDP-43 loss-of-function (LOF) involved in neuronal excitability. Left, integration of TDP-43 mis-spliced genes derived from purified MN11, i3Neurons9 and TDP-43-low neuronal nuclei41 yields 522 genes; 47 are involved in the regulation of ‘membrane potential’ or ‘synaptic signaling’. Right, two genes (KCNQ2 and CACNA1E) are mis-spliced in all three datasets. c, Sashimi plot depicting HISAT2-mapped sequencing coverage along exons 4–6 of KCNQ2. The gene model indicates the locations of exons and introns. Junction spanning reads mapping to the canonical junctions (exons 4–5 and 5–6) are displayed with solid lines, and de novo junction (exons 4–6) reads are displayed with a dashed line. Read counts and percent spliced index (PSI) scores for each splice junction are denoted. KCNQ2 exon skipping is only detected under TDP-43 depletion. siTDP-43, siRNA against TDP-43; siSCR, scrambled control siRNA. d, RT–PCR assay shows KCNQ2 mis-splicing in cortical neurons depleted of TDP-43 by siRNA. e,f, RT–qPCR of mis-spliced KCNQ2∆E5 that increases (e) and total KCNQ2 transcript that remains unaltered (f) after TDP-43 depletion. For e and f, circles represent n = 3 biological replicates, values represent mean expression; error bars, s.e.m. g–i, TDP-43 directly binds to KCNQ2 pre-mRNA. g, iCLIP sequencing coverage9 in the KCNQ2 locus suggests that TDP-43 binds KCNQ2. TDP-43 consensus motifs (UGNNUG) and (UG)n simple repeat are shown below the gene model. RIP amplicon used in h and i is indicated. h, Cross-linking immunoprecipitation followed by RT–PCR analysis shows enrichment of KCNQ2 in the TDP-43-bound fraction compared to IgG immunoprecipitates (IP) using the same quantity of lysate for IPs. i, Quantification of results present in h. Circles represent n = 3 biological replicates; values represent mean relative enrichment; error bars, s.e.m. For e, f and i, P values are the result of an unpaired two-sided t-test.

TDP-43 is required for the inclusion of a constitutive exon in KCNQ2

The identification of KCNQ2 as a differentially spliced gene in TDP-43-depleted MNs (Fig. 1a) suggested a potential connection between TDP-43 dysfunction and neuronal excitability. To investigate this connection further, we integrated splicing changes from three datasets examining TDP-43-depletion (iPS cell-derived MNs11, iPS cell cortical neurons9 and ALS/FTD neuronal nuclei41) to arrive at 522 significantly differentially spliced genes (Fig. 1b, left and Extended Data Fig. 1d, left). Consistent with our hypothesis, this stringent set was enriched for genes with connections to human phenotypes such as ‘motor seizures’, ‘abnormal motor function’ and related terms (Supplementary Table 1). Intersecting differentially spliced genes with Gene Ontology terms such as ‘regulation of membrane potential’ and ‘synaptic signaling’ highlighted 47 target genes (Fig. 1b, right and Extended Data Fig. 1d, right), only two of which were commonly affected across all three datasets: KCNQ2 and the voltage-gated calcium channel CACNA1E (Fig. 1b, right). Critically, a similar analysis integrating gene expression rather than splicing alterations did not yield common targets dysregulated in all three datasets (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f). Although the TDP-43-dependent modulation of CACNA1E represents the preferential splicing of a known annotated isoform (Extended Data Fig. 1g), loss of TDP-43 results in the skipping of exon 5 in the KCNQ2 transcript (Fig. 1c). Notably, this is not an annotated cassette exon, as we were unable to detect regulated alternative splicing at this locus in diverse human central nervous system (CNS) tissue. The unexpectedly skipped exon codes for a deeply conserved segment of the ion channel (Extended Data Fig. 1h), including the entire S5 transmembrane helix and a portion of the pore loop that conducts K+ ions (Extended Data Fig. 1i). Therefore, we categorize this alteration as an aberrant splicing event and refer to the resulting exon 5 skipped transcript as KCNQ2∆E5.

We next used PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) coupled with Sanger sequencing to validate the presence of KCNQ2∆E5 in iPS cell-derived cortical neurons42 (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1j) and spinal MNs43 (Extended Data Fig. 2a) that were depleted of TDP-43. The product corresponding to exon 5 skipping was substantially upregulated in neurons (~60-fold) treated with short interfering RNA (siRNA) against TDP-43 but not in neurons treated with a scrambled control siRNA sequence (Fig. 1e). KCNQ2∆E5 was also identifiable in published TDP-43 loss-of-function RNA-seq datasets generated using SH-SY5Y and SK-N-BE(2) neuroblastoma lines9, as well as i3 cortical neurons9, suggesting that this target is reliably sensitive to TDP-43 levels across neurons and neuron-like cells (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Moreover, using SH-SY5Y cells expressing the aggregation-prone version of TDP-43 in which the Q/N-rich domain is repeated 12 times, we also observed robust exclusion of KCNQ2 exon 5, further corroborating that KCNQ2 is highly responsive to TDP-43 dysfunction (Extended Data Fig. 2c–e). Other recently discovered human neuronal TDP-43 targets, such as STMN2 and UNC13A, undergo cryptic exon inclusion that results in a decrease of the host gene either through premature transcription termination or nonsense-mediated decay9,10,11,12,13. However, skipping of exon 5 in KCNQ2 does not alter the reading frame or induce a premature termination codon, and analysis by RT–quantitative PCR (qPCR) showed that the overall expression levels of KCNQ2 in TDP-43-depleted neurons remain unchanged despite the dramatic shift to KCNQ2∆E5 (Fig. 1f).

TDP-43 is known to bind UG repeats within long introns44. To explore whether TDP-43 may directly associate with KCNQ2 mRNA, we first examined sequence content surrounding the skipped exon 5. Although there are many UG dinucleotides within the 5 kb locus containing exon 5 and flanking introns, we observed an annotated ~1 kb-long simple repeat 6 bp upstream of exon 5 (Fig. 1g). This region consists of UG repeats, suggesting the potential for direct TDP-43 recruitment. Mapping of published TDP-43 individual nucleotide resolution UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (iCLIP) datasets in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells9 to this locus showed broad TDP-43 binding within KCNQ2, including upstream of exon 5 (Fig. 1g, top). To validate this CLIP enrichment, we UV-crosslinked SH-SY5Y cells and used a protocol to immunoprecipitate TDP-43 and associated RNA targets. We detected specific and TDP-43-immunoprecipitate-dependent KCNQ2 pre-mRNA enrichment (Fig. 1h,i). Notably, although the human and mouse KCNQ2 exons are highly conserved, the intronic regions around exon 5 show very little homology (Extended Data Fig. 2f). Accordingly, skipping of Kcnq2 exon 5 is not detected in published TDP-43 mouse models45 (Extended Data Fig. 2g,h), suggesting that this splicing event is not similarly regulated in mice, like other TDP-43 targets such as STMN2 and UNC13A9,10,11,12. To directly test this hypothesis, we differentiated MNs from mouse embryonic stem cells and knocked down Tardbp using siRNA and observed no evidence for mis-splicing of Kcnq2 exon 5 (Extended Data Fig. 2i). To exclude the possibility that mouse Kcnq2 is erroneously spliced past exon 5, we examined published RNA-seq datasets from mouse brains depleted of Tdp-43 (ref. 45) and again found no evidence for Tdp-43 dependent mis-splicing (Extended Data Fig. 2j). Our findings demonstrate that TDP-43 has a critical role in ensuring the integrity of KCNQ2 processing in human neurons that is not conserved in mice.

TDP-43 processing of KCNQ2 is altered in postmortem ALS/FTD CNS

The identification of KCNQ2 mis-splicing in iPS cell-derived neurons depleted of TDP-43 prompted us to investigate the extent of this event in ALS postmortem tissue. We first examined RNA-seq datasets generated by the Target ALS/New York Genome Center, consisting of 1,124 libraries of diverse tissues from patients with ALS (216), non-neurological disease controls (28) and individuals with other neurological diseases (8) (Fig. 2a). To evaluate the state of KCNQ2 processing, we counted sequencing reads that stringently aligned to the KCNQ2 exon 4/6 boundary and thus correspond to the aberrant KCNQ2∆E5 mRNA. (Fig. 2b). This analysis revealed that KCNQ2 misprocessing was detectable and highly specific to the ALS cohort (Fig. 2c). Evidence for KCNQ2∆E5 was found in most CNS tissues, including different spinal cord regions, as well as in temporal, frontal and motor cortex within the brain (Fig. 2d). Notably, as much as 29.5% of motor cortex and 17.3% of lumbar spinal cord samples exhibited KCNQ2∆E5, regions that are notably involved in the pathophysiology of ALS/FTD (Fig. 2d). This contrasted with only 4.1% and 4.3% of cerebellum and occipital cortex samples, respectively, which are two regions not typically affected in patients (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3a). These tissue-specific differences in the detection of KCNQ2∆E5 probably reflect differences in neuronal cell type composition, disease burden, TDP-43 pathology and KCNQ2 expression level within the CNS (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). Comparison of aberrant KCNQ2 levels with other known TDP-43 targets, like STMN2 and UNC13A, further revealed differential detection of aberrantly spliced products, with STMN2 misprocessing prominent within the spinal cord and motor cortex, and UNC13A misprocessing within the motor cortex (Extended Data Fig. 3d). For these genes as well, differential levels of mis-splicing across tissues and neuronal subtypes are not strictly driven by their relative abundance (Extended Data Fig. 3b–e).

a, Target ALS/New York Genome Center RNA-seq datasets, including 118 non-neurological controls, 982 ALS and 24 other neurological disease samples from distinct CNS regions. b, Strategy to detect KCNQ2∆E5 reads. c, Violin plots of CNS samples with KCNQ2∆E5 reads in RNA-seq datasets stratified by disease status reveal specificity to ALS. d, Percentage of ALS samples across CNS regions with KCNQ2∆E5 transcripts. Red shade intensity is relative to the proportion of samples with detectable KCNQ2∆E5. e, Violin plots of ALS samples with KCNQ2∆E5 reads in RNA-seq datasets stratified by genetics reveal specificity to TDP-43 pathologies. In c and e, each point represents a unique sample, and the y axis indicates the number of unique KCNQ2∆E5 reads. P values are the result of an unpaired one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. f–i, RT–qPCR analysis in brain samples from patients with ALS/FTD (n = 89) or controls (n = 27) for KCNQ2∆E5 (f) and wild type KCNQ2 (g). Boxplots represent interquartile range (IQR), whiskers indicate IQR limits ±1.5× IQR. h,i, KCNQ2∆E5 abundance increases with pTDP-43 levels (h), and KCNQ2∆E5 abundance is higher in individuals with early disease onset (i). For additional statistics, see Supplementary Table 2. For f–i, points indicate data obtained from unique postmortem samples. P values are the result of linear regression models adjusted for age at death, sex and RIN. j,k, Abundance of KCNQ2∆E5 in TDP-43-high and TDP-43-low neuronal nuclei from patients with ALS/FTD with C9orf72 hyperexpansions41. j, Top, schematic of neuronal nuclei sorted by flow cytometry into fractions with high and low TDP-43 levels. Bottom, quantification of KCNQ2 shows 100% wild type KCNQ2 transcripts in TDP-43-high nuclei and ~50% reduction in TDP-43-low nuclei and a concomitant ~50% increase in KCNQ2∆E5 transcripts. Violin plots of KCNQ2 levels; each point represents a unique sample. k, Sashimi plot depicting HISAT2-mapped sequencing coverage along exons 4–6 of KCNQ2 in purified neuronal nuclei from individual patients. Canonical junctions (exons 4–5 and 5–6) are displayed with solid lines; KCNQ2 exon 5 skipping reads are displayed with red dashed lines; read counts are denoted. KCNQ2 exon skipping is only detected in TDP-43-low neurons.

As KCNQ2 splicing is dependent on TDP-43 functional activity in iPS cell-derived neurons, we next evaluated this correlation in postmortem patient tissue. Cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregation is observed in an overwhelming majority of patients with ALS (>95%) and is typically accompanied by nuclear loss-of-function3. Therefore, to interrogate whether detection of KCNQ2∆E5 was related to TDP-43 status, we grouped ALS datasets into those known to have typical cytoplasmic TDP-43 neuropathology (C9orf72 and sporadic cases) and those without (patients with SOD1 mutations; non-TDP-43). We found that KCNQ2∆E5 was only observed in patient samples that typically exhibit TDP-43 aggregation (Fig. 2e). To provide more direct evidence for this relationship, we analyzed RNA from a cohort of 89 frontal cortex brains from patients diagnosed with ALS/FTD and 27 controls from the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank (Supplementary Table 2). Along with documented clinical history, these samples were characterized for TDP-43 pathology by immunohistochemistry and a phosphorylated TDP-43 (pTDP-43) immunoassay. Using RT–qPCR primers that distinguish wild type (WT) and KCNQ2∆E5, we found a highly significant difference, with KCNQ2∆E5 detected exclusively in patient samples (P < 0.0001 adjusting for age, sex and RNA integrity number (RIN); Supplementary Table 2), while the levels of WT KCNQ2 transcript were not different (P = 0.9947 adjusting for age, sex and RIN; Supplementary Table 2) (Fig. 2f,g). Although the RT–qPCR assay can detect unique KCNQ2∆E5 transcripts, it is probably not sensitive enough to detect a potential reduction in WT KCNQ2 levels, as these RNA samples were produced from bulk cortical tissue, and TDP-43 pathology is typically seen only in a small proportion of neurons41. Critically, the level of misprocessed KCNQ2∆E5 was directly and significantly associated with the level of pTDP-43 (higher KCNQ2∆E5 = higher pTPD-43; P < 0.0001, adjusting for age, sex, RIN and gene mutation status; Fig. 2h and Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, there was an inverse relationship between the abundance of KCNQ2∆E5 and the age of disease onset (higher KCNQ2∆E5 = lower age of onset; P = 0.0053, adjusting for sex, RIN and gene mutation status; Fig. 2i and Supplementary Table 2), suggesting a potential contribution of KCNQ2 dysfunction to disease pathophysiology. Although there was also an indication that the higher abundance of KCNQ2∆E5 was associated with shorter disease duration, this was not statistically significant after correcting for confounding variables (P = 0.0322, adjusting for age at onset, sex, RIN and gene mutation status; Extended Data Fig. 3f and Supplementary Table 2).

Lastly, to assess the extent of KCNQ2 mis-splicing within purified patient neurons with TDP-43 dysfunction, we analyzed a previously published RNA-seq dataset41 in which neuronal nuclei from postmortem brains of individuals with ALS/FTD with C9orf72 expansions were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on TDP-43 abundance41. We specifically compared the transcriptomes of neuronal nuclei with high and low TDP-43 levels. Strikingly, for six out of six individuals, we observed reads indicative of KCNQ2∆E5 exclusively in neuronal nuclei with low TDP-43 levels (Fig. 2j,k). The level of disruption in splicing amounted to ~50% of total KCNQ2 gene expression, suggesting that if KCNQ2∆E5 encodes a dysfunctional protein, it could reduce half of the total KCNQ2 available to neurons (Fig. 2j,k). Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that KCNQ2∆E5 is a molecular biomarker of TDP-43 ALS/FTD pathology.

KCNQ2∆E5 exhibits dominant negative loss-of-function activity

Having established that the KCNQ2∆E5 variant is induced by TDP-43 loss-of-function in iPS cell-derived neurons and ALS/FTD patient tissue, we next wondered how mis-splicing of this transcript might affect the biology of the encoded protein. KCNQ2 encodes a voltage-gated, slow-activating and non-inactivating K+ channel (KCNQ2 or Kv7.2) subunit that is expressed very early in the developing brain and forms homo-and hetero-tetrameric K+ channels in combination with KCNQ3 (Kv7.3)46,47. The resulting Kv7 channels underlie the repolarizing M-current, which contributes to the resting membrane potential (RMP), action potential (AP) threshold and limits repetitive firing during prolonged depolarizing inputs48,49. Heterozygous mutations in KCNQ2 can cause epilepsy ranging in severity from benign self-limiting familial neonatal epilepsy (SLFNE) to severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE), which is characterized by neonatal seizures and a spectrum of developmental deficits50,51,52,53. The drastically different clinical outcomes between SLFNE and DEE cases are associated with the impact of the variants on channel function that can cause haploinsufficiency or dominant negative loss-of-function effects. To interrogate the function of the KCNQ2∆E5-encoded protein, we generated a KCNQ2 expression plasmid lacking the corresponding exon 5. We transfected this plasmid (KCNQ2∆E5) or WT KCNQ2 (KCNQ2WT) in a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line that stably expresses KCNQ3 (ref. 39) and performed patch-clamp experiments to measure K+ current density across a series of voltage steps (Fig. 3a,b). Untransfected CHO cells expressing KCNQ3 exhibit negligible endogenous outward currents39; therefore, any measurements reflect the activity of the heterologous KCNQ2/KCNQ3 tetramer. To record across a large cohort of cells (n = 24–154), we conducted high-throughput automated patch clamp by using the SynchroPatch system (Fig. 3b, right). As an additional control, we included constructs expressing two recurrent, severe KCNQ2 DEE-associated variants known to exert a dominant negative effect (KCNQ2G279S and KCNQ2T274M)54. We first interrogated channel function in the homozygous state, in which the WT channel or mutant transgenes were introduced into KCNQ3-expressing CHO cells (Fig. 3b, top left). These experiments clearly showed that in stark contrast to the WT, KCNQ2∆E5-expressing cells conducted no outward currents (Fig. 3c–e, Extended Data Fig. 4d,e and Supplementary Table 3). As KCNQ2 functions in tetrameric complexes, we also considered whether the TDP-43-specific KCNQ2∆E5 possesses dominant negative activity. To examine this possibility, we tested channel function in the heterozygous state, in which mutant and WT KCNQ2 constructs were co-expressed at a 1:1 ratio (Fig. 3b, bottom left). KCNQ2∆E5 demonstrated a sharp reduction in current density at all voltage steps relative to WT/WT channels (approximately 44% reduction at +40 mV), an effect identical to DEE-KCNQ2T274M and slightly less severe than DEE-KCNQ2G279S (Fig. 3f–h, Extended Data Fig. 4b,c, Extended Data Fig. 4f,g and Supplementary Table 3). Notably, KCNQ2∆E5 did not impact the activation kinetics of the co-expressed WT KCNQ2 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). A comparison of the impact of KCNQ2∆E5 on conductance with other KCNQ2 variants (n = 74), including ones associated with SLFNE and DEE cases that we previously analyzed using the same assay54, clearly demonstrated that KCNQ2∆E5 acted like the average severe DEE variant typically associated with dominant negative loss-of-function activity (Fig. 3i).

a, Amino acid sequence (220–280) and illustration for KCNQ2WT, KCNQ2∆E5 and DEE variants KCNQ2G279S and KCNQ2T274M. Exon 5 deletion is shown by the dashed line. b, Schematic outlining heterologous expression model and SyncroPatch recordings. Left, KCNQ2 transgenes are transfected into CHO-Kv7.3 cells either alone (homozygous; top left) or with KCNQ2WT (heterozygous; bottom left). Right, cells are plated into 384-well plates for automated voltage-clamp recordings. c, SyncroPatch results for homozygous expression of KCNQ2 transgenes. Summary data (means; error bars, s.e.m.) for peak outward current density as a function of command voltage. P value determined by one-way ANOVA, #P < 0.001 for all steps starting at −50 to +40 mV for KCNQ2∆E5, G279S and T274M relative to WT. n represents cells denoted within the panel. d, Representative KCNQ2 current (XE991-sensitive) traces. No significant current is observed from KCNQ2∆E5, KCNQ2T274M or KCNQ2G279S co-expressed with KCNQ3. Scale bar, 50 pA, 200 ms. e, Peak current density at +40 mV plotted as a percentage of KCNQ2WT current (means; error bars, s.e.m.); n represents cells as in c. P value determined by one-way ANOVA, pairwise multiple comparisons by Holm–Sidak method. Circle represents the average of all cells, which are shown individually in Extended Data Fig. 4d,e. f, SyncroPatch results for heterozygous (×2) expression of KCNQ2 transgenes. Summary data (means; error bars, s.e.m.) for peak outward current density. One-way ANOVA, #P < 0.001 for all steps starting at −40 to +40 mV for KCNQ2∆E5, G279S and T274M relative to WT; n represents cells denoted within the panel. g, Representative traces as in d. Scale bar, 50 pA, 200 ms. h, Peak current density at +40 mV plotted as a percentage of KCNQ2WT (×2) current (means; error bars, s.e.m.); n represents cells as in f. P value determined by one-way ANOVA, pairwise multiple comparisons by Holm–Sidak method. Each circle represents the average of cells recorded from n = 3 independent experiments, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 4f,g. See Supplementary Table 3 for statistics for c and f. i, Top, schematic of correlation between clinical severity of KCNQ2 variants and M-current reduction. Variants are classified as PV (non-pathogenic population variants), SLFNE (mild cases of epilepsy) and DEE (severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy). Bottom, SyncroPatch data from grouped KCNQ2 variants (heterozygous with KCNQ2WT, previously reported54) in comparison to KCNQ2∆E5. Each circle represents the mean value recorded from all cells of a particular variant. PVs (n = 15) result in 101 ± 8% of WT, SFLNE (n = 15) in 74.1 ± 6% of WT and DEE variants (n = 40) in 56.6 ± 5% of WT current density. KCNQ2∆E5-expressing cells are identical to the average of DEE variants (56.6 ± 5% of WT). No statistics were run; error bars, s.e.m. j, Top, schematic of cell surface biotinylation experiments. Bottom, western blot of input and cell surface fractions from WT/WT (GFP–KCNQ2WT + mCh–KCNQ2WT) and ∆E5/WT (GFP–KCNQ2∆E5 + mCh–KCNQ2WT). k,l, Quantification of surface levels of GFP–KCNQ2 (k) and mCh–KCNQ2 (l) normalized to transferrin receptor (TfR). Relative intensities are normalized to WT/WT in each experiment and plotted as fold change. Each shape represents the result from one of n = 3 independent experiments. P value determined by two-tailed paired t-test; error bars, s.e.m.

Structure prediction suggests that the exon skipping event in KCNQ2 mRNA is translated into an aberrant protein by disrupting the formation of a functional pore domain (Extended Data Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 4a), which may explain decreased ion conductance. However, given the severity of this disruption within a highly conserved transmembrane region of the protein, it is also possible that KCNQ2∆E5 does not traffic properly to the membrane. To address this possibility, we generated a series of constructs with WT or aberrant KCNQ2∆E5 transgenes fused to GFP and introduced these into KCNQ3-expressing CHO cells. We first used manual patch clamp to confirm that the fusion did not impede the functional capacity of the WT channel and that the fused KCNQ2∆E5 protein was still unable to conduct current (Extended Data Fig. 4h). We then performed cell surface biotinylation assays to quantify the amount of WT KCNQ2 and KCNQ2∆E5 protein that localizes to the membrane (Fig. 3j, top). Total cell lysate (input), cell surface and flow-through fractions were analyzed by western blot for the membrane marker transferrin receptor and negative control histone H3 to confirm enrichment of cell surface proteins (Fig. 3j, bottom and Extended Data Fig. 4i,j). Cell surface fractions isolated from CHO cells transfected with GFP-tagged WT KCNQ2 or KCNQ2∆E5 that were co-expressed with mCherry-tagged WT KCNQ2 showed a dramatically lower surface abundance of monomeric mutant KCNQ2 compared to WT (>90% reduction) (Fig. 3k). Notably, we also observed an approximately 25% lower amount of mCherry-tagged WT KCNQ2 localized to the cell surface when co-expressed with mis-spliced KCNQ2 protein, suggesting a dominant negative trafficking effect (Fig. 3l). These results demonstrate that KCNQ2∆E5 protein does not traffic to the membrane efficiently and that 50% of KCNQ2∆E5 is sufficient to disrupt the appropriate trafficking of as much as 25% of WT protein. The dominant negative effect of KCNQ2∆E5 is in line with the fact that tetrameric Kv7 channels are typically assembled within the ER and subsequently transported to the membrane55. Collectively, our characterization reveals that TDP-43 dysfunction causes the formation of an aberrant KCNQ2 protein variant that is unable to conduct current or localize to the cell surface and exerts dominant negative effects.

KCNQ2∆E5 accumulates in the ER and causes neuronal hyperexcitability

We next sought to address the relevance of these findings in the context of human neurons. To interrogate the impact of KCNQ2∆E5 on neuronal homeostasis in the absence of all the additional effects of TDP-43 dysfunction, we used CRISPR–Cas9 genome engineering to delete exon 5 in a healthy control human embryonic stem cell line (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 5a). We generated a clone with a homozygous deletion of KCNQ2 exon 5 (KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5) and confirmed that the cells had correct on-target zygosity by performing an allele copy number assay (Extended Data Fig. 5b) and a normal karyotype (Extended Data Fig. 5c). We then differentiated the KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 and parental isogenic WT cell lines into cortical excitatory glutamatergic neurons42,43 (Extended Data Fig. 5d), validated the KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 variant expression (Fig. 4b) and performed immunocytochemistry with a KCNQ2 antibody to assess the subcellular localization of the endogenous protein after 50–60 days in culture. To mark the axon initial segment (AIS), which is the site where KCNQ2 channels are predominantly localized in mature neurons, we immunostained cells with an antibody against ankyrin-G (ANK3). We found that WT neurons exhibited diffuse KCNQ2 signal in the cell body and, occasionally, a distinct signal within the AIS (Fig. 4c, top). In stark contrast, all KCNQ2∆E5-derived neurons exhibited an irregular KCNQ2 distribution pattern with very little to no signal within the AIS and dramatic intracellular focal accumulations within the cell body (Fig. 4c, bottom and Extended Data Fig. 5e). Quantification revealed that 100% of mutant neurons exhibited KCNQ2 accumulation (Fig. 4d), while analysis of the KCNQ2 signal distribution showed a significant increase in standard deviation (Fig. 4e), mean and maximum intensity (Extended Data Fig. 5f,g) in mutant neurons relative to isogenic controls, suggesting severe mislocalization of the TDP-43-associated KCNQ2∆E5 protein variant. The dramatic focal accumulation of mis-spliced protein prompted us to determine the precise site of localization. Immunostaining with the ER marker calnexin revealed substantial overlap, demonstrating that the majority of KCNQ2∆E5 protein is retained within the ER and does not traffic to the neuronal surface membrane (Fig. 4f), in agreement with the surface localization analysis in heterologous cells (Fig. 3j–l).

a, Schematic of CRISPR–Cas9 editing of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to generate homozygous KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 lines and differentiation into cortical excitatory neurons. b, RT–PCR shows that KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 neurons express KCNQ2∆E5 and KCNQ2WT/WT express KCNQ2WT. c, Representative immunocytochemical images of neurons stained with DAPI, MAP2, KCNQ2 and ANK-G. Arrowheads denote the beginning of AIS. Asterisk (*) denotes KCNQ2 localization in the AIS for WT (top) and accumulated in the soma for KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 neurons (bottom). Yellow dashed line outlines the cell body. Scale bar, 10 μm. d, Percentage of WT (n = 51, 0%) and KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 (n = 79, 100%) neurons with somatic accumulation of KCNQ2. e, Quantification of KCNQ2 signal intensity variation. Statistical significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.; each circle corresponds to one neuron. a.u., arbitrary units. f, Representative image of KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 neuron stained with DAPI, MAP2, calnexin and KCNQ2. Top, maximum Z-projection; middle, 3D views with neuron rotated forward; bottom, 3D views from below. g, Representative raster plot of neuronal activity recorded in a MEA well for control (top) and KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5 (bottom). Rows depict individual electrodes; black lines represent single spikes; blue lines indicate ‘bursts’. h–o, Longitudinal analysis of neuronal MEA recordings for days 9–43 (h–k) or 12–43 (l–o). Data are presented as means from n = 3 independent experiments (n = 59 wells for WT and n = 64 for KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5); circles represent means; shaded areas, s.e.m. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used for h, i and l; mixed-effects model restricted maximum likelihood) for j, k, m, n and o. P values: in black indicate genotype effects and in pink reflect genotype × day interactions. MEA metrics are indicated within each panel. p, Experimental schematic (top) and representative raster plot from MEA wells (bottom) during treatment with the Kv7 agonist ICA-069673 (1 μM). For each metric, pre-ICA-069673 and post-ICA-069673 values are represented as the percent of baseline values (right). Each circle-pair represents the change in activity recorded from a well (total number of wells from two replicate MEA plates were combined for analysis: n = 20 for WT and n = 19 wells for KCNQ2∆E5/∆E5. P value determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To determine the neurophysiological implications of the KCNQ2∆E5 variant, we plated equal numbers of mutant and isogenic control neurons on multi-electrode arrays (MEAs) and recorded spontaneous neuronal activity over the course of several weeks in culture (days 10–45; n = 3 independent differentiations; Fig. 4g–o). Neurons started firing after 10–15 days and became progressively more active thereafter (Fig. 4h). Although there were only minor differences in the number of active electrodes (Fig. 4h), KCNQ2∆E5 neurons exhibited a dramatic shift in their pattern of firing activity (Fig. 4g), with a significant increase in the number of spikes (Fig. 4i), weighted mean firing rate (Fig. 4j), increased irregularity as measured by an increase in inter-spike interval coefficient of variation (Fig. 4k) and several bursting metrics relative to isogenic WT controls (Fig. 4l–o). Most of their spikes occurred within bursts, reflected by a significant increase in number of bursts (Fig. 4l), burst percentage (Fig. 4m) and number of spikes per burst (Fig. 4n), while there were only minor effects on the duration of each burst (Fig. 4o). Notably, treatment of KCNQ2∆E5 neurons wih the Kv7 agonist ICA-069673 had no significant effect on firing activity (active electrodes, weighted mean firing rate, number of bursts), consistent with non-functional Kv7 channels, whereas it caused a substantial reduction in most metrics in isogenic WT controls (Fig. 4p). These widespread alterations in neuronal spiking behavior are consistent with the critical role of Kv7 channels in regulating excitability39.

TDP-43-depleted MNs exhibit intrinsic hyperexcitability that can be rescued by splice-modulating KCNQ2 ASOs

Having established that expression of KCNQ2∆E5 alone is sufficient to induce dramatic neuronal excitability alterations, we next sought to dissect the contribution of this mis-spliced protein in the context of TDP-43 loss. We first set up a screening assay to identify splice-modulating ASOs (smASOs) that selectively repress the expression of the KCNQ2∆E5 isoform in iPS cell-derived spinal MNs56 (Extended Data Fig. 6a). We designed a series of ~20 bp ASOs with 2’-O-methoxyethyl sugars and phosphorothioate linkages, spanning the intronic regions upstream and downstream of exon 5, including the simple UG-rich repeat (Fig. 5a, top and Supplementary Table 4). We then differentiated WT MNs, depleted TDP-43 (Extended Data Fig. 6b), delivered the smASOs gymnotically57 and quantified the expression of mis-spliced KCNQ2∆E5 by RT–qPCR (Fig. 5a, bottom). We found several candidate smASOs that significantly repressed the level of KCNQ2∆E5, which targeted both the UG-rich repeat sequence as well as the 3’ flanking intronic region of exon 5 (Fig. 5a).

a, Top, KCNQ2 and smASO design strategy. Bottom, RT–qPCR of KCNQ2∆E5 expression. P value determined by an unpaired, two-tailed t-test of each smASO relative to splice-modulating control ASO (smCTRL). b, Experimental schematic: iPS cell MNs are treated with a control ASO (CTRL) or an ASO to knock down TDP-43 (TDP-KD) and smASOs between days 20 and 30 for analysis; images of neurons analyzed by patch clamp. Three treatment groups: (1) CTRL + smCTRL, (2) TDP-KD + smCTRL and (3) TDP-KD + smKCNQ2. c, RT–qPCR of TARDBP expression. P value determined by a paired, two-tailed t-test; ns: not significant. d, RT–PCR shows KCNQ2 mis-splicing upon TDP-43 KD and partial rescue with smASO treatment. e, RT–qPCR of KCNQ2∆E5. P value determined by a paired, two-tailed t-test. For a, c and e, each circle represents one of n = 4 biological replicates; data are presented as means; error bars, s.e.m. f, Representative traces of spontaneous APs counted while cells were at RMP for all three groups. Asterisks denote individual spontaneous APs; black dashed line denotes 0 mV; colored dashed line denotes RMP. Scale bar, 10 mV, 1 s. g, RMP recorded from all three groups; number of neurons: (1) n = 53, (2) n = 63, (3) n = 30. P value determined by one-way ANOVA (F2,144 = 8.3, P = 0.0004) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. h, Spontaneous AP frequency recorded from all three groups; number of neurons: (1) n = 54, (2) n = 63, (3) n = 30. P value determined by one-way ANOVA (F2,143 = 16.82, P < 0.0001) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. i, Representative traces of the post-burst mAHP. Scale bar, 5 mV, 250 ms. j, Post-burst mAHP recorded from all three groups; number of neurons: (1) n = 51, (2) n = 55, (3) n = 28. P value determined by one-way ANOVA (F2,131 = 4.7, P = 0.0105) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. k, Post-burst sAHP recorded from all three groups; number of neurons: (1) n = 51, (2) n = 55, (3) n = 28. P value determined by one-way ANOVA (F2,131 = 5.01, P = 0.008) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For g, h, j and k, each circle represents neurons recorded from n = 4 biological replicates. Data are presented as means; error bars, s.e.m.

We next set up an experimental paradigm to interrogate the intrinsic excitability of mature iPS cell MNs by whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiological analysis (Fig. 5b). In these experiments, conducted at Northwestern University, we depleted TDP-43 levels by treating MNs with an RNase H-dependent gapmer ASO (Fig. 5c), and repressed mis-spliced KCNQ2∆E5 by treating with a lead candidate KCNQ2 smASO identified in our screen (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d), or a scrambled control ASO of matched chemistry (Fig. 5d,e). The substantial reduction in TDP-43 levels (~85% reduction) (Fig. 5c) caused a substantial increase in the expression level of KCNQ2∆E5 (~37-fold increase), which was significantly, but not completely, repressed by simultaneous treatment with the KCNQ2 smASO (~35% reduction) (Fig. 5d,e). Kv7 encoded M-current contributes to the RMP and AP thresholds that attenuate excitability, as well as to modulate the post-burst afterhyperpolarization (AHP), which limits repetitive AP firing48,49,58. Therefore, we performed current-clamp measurements to analyze RMP and AP properties, spontaneous firing and post-burst AHP (Fig. 5f–k and Extended Data Fig. 6e–n). TDP-43 knockdown (KD) MNs exhibited a significantly depolarized RMP relative to MNs treated with scrambled control ASO (Fig. 5f,g). Consistent with a depolarized state, TDP-43 depletion caused hyperexcitability as MNs were more active than controls, as measured by the number of spontaneous APs recorded at rest (Fig. 5f,h). These changes, which are consistent with dysfunctional Kv7 channels, were restored in MNs treated with the KCNQ2 smASO. The treatment resulted in a significant recovery in RMP and associated reduction in spontaneous AP frequency (Fig. 5f–h). At the same time, although there was a substantial reduction in post-burst medium AHP (mAHP) and slow AHP (sAHP) upon TDP-43 KD, these properties were not restored by KCNQ2 smASO treatment (Fig. 5i–k). Similarly, changes in fast AHP and mAHP measured following a single AP were not restored by KCNQ2 smASO treatment (Extended Data Fig. 6m,n), which may either reflect the contribution of other K+ channels to them or insufficient repression of KCNQ2∆E5 by the smASO. We did not find any substantial effects upon TDP-43 KD on other intrinsic cell or AP properties (Extended Data Fig. 6e–l). These experiments suggest that TDP-43 loss causes intrinsic neuronal depolarization and hyperexcitability that can be rescued by repressing mis-spliced KCNQ2∆E5.

TDP-43-depleted cortical neurons exhibit hyperexcitability that can be rescued by KCNQ2 smASOs

To increase the rigor of our findings and substantiate their relevance across other neuronal subtypes, we performed a series of patch-clamp measurements in iPS cell-derived cortical neurons59 that were independently conducted at University College London. We used a recently developed iPS cell line in which endogenous TARDBP was edited to harbor a HaloTag, which allows for complete degradation of TDP-43 through a proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC)60 (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Although tagging TDP-43 slightly compromises its function, HaloPROTAC-mediated KD caused a substantial increase in the expression of KCNQ2∆E5 (Extended Data Fig. 7c). We differentiated NGN2-based cortical neurons59 and performed whole-cell patch-clamp analysis 2 weeks after TDP-43 KD (Fig. 6a, top). Voltage-clamp recordings revealed a significant reduction in M-current deactivation kinetics in neurons depleted of TDP-43 relative to controls (Fig. 6c). Critically, acute treatment with the M-current inhibitor XE991 showed a reduction in control neurons but had no effect in TDP-43 KDs, suggesting loss of Kv7 channels (Fig. 6c). To dissect the contribution of KCNQ2 mis-splicing to these TDP-43-dependent effects, we treated TDP-43 KD neurons with the smASO and found a significant, but not complete, repression in the expression of KCNQ2∆E5 (Fig. 6a, bottom and Fig. 6b). The repression of KCNQ2∆E5 expression resulted in a marked recovery of M-current, which was responsive to XE991 treatment (Fig. 6d).

a, Experimental schematic: cortical neurons were differentiated from HaloTag TDP-43 iPS cells and treated with vehicle (CTRL) or PROTAC to knock down TDP-43. Some TDP-43 KD neurons were also treated with control smASO or smKCNQ2 to repress KCNQ2∆E5. b, Left, RT–PCR assay shows KCNQ2 mis-splicing upon TDP-43 KD and partial rescue with smASO treatment. Right, RT–qPCR of KCNQ2∆E5. P value determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Data are means; error bars, s.e.m. Circles are one of n = 3 biological replicates. c, Left, M-current from CTRL (n = 29) and TDP-43 KD (n = 36) neurons. P value determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Right, representative traces and measurements of individual neurons for pre-XE991 and post-XE991 treatment (n = 7). P value determined by paired, two-tailed t-test. d, Left, M-current from TDP-43 KD + smCTRL (n = 27) and TDP-43 KD + smKCNQ2 (n = 28) neurons. P value determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Right, representative traces and measurements of individual neurons for pre-XE991 and post-XE991 treatment (n = 8). P value determined by paired, two-tailed t-test. For c and d, circles represent one cell; data are means; error bars, s.e.m. Scale bar, 100 pA, 500 ms. e,f, Representative traces of spontaneous APs. e, CTRL neurons were not firing at rest (CTRL, −XE991), while XE991 caused increasing spiking (CTRL, +XE991). TDP-43 KDs were active at rest (TDP-43 KD, −XE991), while XE991 did not cause significant firing changes (TDP-43 KD, +XE991). Scale bar, 20 mV, 500 ms. f, TDP-43 KD + smCTRL neurons were active at rest (TDP-43 KD + smCTRL, −XE991) and unresponsive to XE991 (TDP-43 KD + smCTRL, +XE991). TDP-43 KD + smKCNQ2 neurons were quiet at rest (TDP-43 KD + smKCNQ2, −XE991) and responsive to XE991 (TDP-43 KD + smKCNQ2, +XE991). Scale bar, 20 mV, 500 ms. g, Left, RMP from CTRL (n = 29) and TDP-43 KD (n = 35) neurons. Right, RMP from TDP-43 KD + smCTRL (n = 27) and TDP-43 KD + smKCNQ2 (n = 27) neurons. P values determined by unpaired, two-sided t-test; each circle represents one cell. Data are means; error bars, s.e.m. h, Left, spontaneous AP frequency from CTRL (n = 29) and TDP-43 KD (n = 37) neurons. P value determined by unpaired, two-sided t-test. Right, AP measurements of individual CTRL (top) and TDP-43 KD (bottom) neurons for pre-XE991 and post-XE991 treatment. P values determined by paired, two-sided t-test; each circle represents one cell. Data are means; error bars, s.e.m. i, Left, spontaneous AP frequency from TDP-43 KD + smCTRL (n = 27) and TDP-43 KD + smKCNQ2 (n = 27) neurons. P value determined by unpaired, two-sided t-test. Right, AP measurements of individual KD + smCTRL (top, n = 9) and KD + smKCNQ2 (bottom, n = 8) neurons for pre-XE991 and post-XE991 treatment. P values determined by paired, two-sided t-test; each circle represents one cell. Data are means; error bars, s.e.m.

Moreover, as in spinal MNs, we found that loss of TDP-43 in these cortical neurons caused a depolarization of the RMP, which was rescued by the smKCNQ2 ASO (Fig. 6e–g). Similarly, TDP-43 KD neurons showed a substantial increase in the frequency of spontaneous AP firing relative to controls (Fig. 6e and Fig. 6h, left). As expected, treating controls with the Kv7 inhibitor XE991 caused an increase in AP frequency, indicative of functional Kv7.2 channels (Fig. 6e and Fig. 6h, top right), while treating TDP-43 KDs with XE991 had no effect, demonstrating the lack of functional Kv7.2 channels downstream of TDP-43 KD (Fig. 6e and Fig. 6h, bottom). These results suggest that the increase in spontaneous AP in TDP-43 KD neurons is driven by dysfunctional Kv7 channels. Remarkably, the smKCNQ2 ASO repressed this spontaneous hyperexcitability and restored the sensitivity of the TDP-43 KD neurons to XE991 treatment (Fig. 6f,i). We did not find any substantial effects on TDP-43 KD on the capacitance or input resistance of cortical neurons (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e). Lastly, reduction of TDP-43 levels caused a more depolarized mAHP (following a single AP) (Extended Data Fig. 7f), a property that was restored by the smKCNQ2 ASO along with its responsiveness to Kv7 inhibition by XE991 (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Notably, although this metric was similarly affected by TDP-43 KD in spinal MNs, smKCNQ2 treatment did not induce a recovery in those cells (Extended Data Fig. 6n).

Altogether, these results demonstrate that in cortical glutamatergic neurons, TDP-43 loss causes intrinsic hyperexcitability driven by KCNQ2 mis-splicing. The use of the smASO across both spinal and cortical neurons addresses a direct cause-and-effect relationship between mis-spliced KCNQ2 and TDP-43-dependent excitability alterations.

KCNQ2 accumulates focally in postmortem neurons from patients with ALS

To investigate the localization of KCNQ2 protein in ALS, we performed immunohistochemistry on spinal cord sections at two independent sites, using two cohorts of postmortem tissue (Supplementary Table 5). First, at Northwestern University, we used sections from three sporadic ALS cases and three non-neurological disease controls to characterize TDP-43 and KCNQ2 levels. We found that in non-neurological control individuals, large MAP2-positive MNs located in the ventral horn of the spinal cord exhibited a diffuse KCNQ2 pattern of immunoreactivity throughout the soma, whereas TDP-43 had clear nuclear localization (Fig. 7a and Extended Data Fig. 8a). In contrast, MNs from patients with ALS exhibited cytoplasmic focal accumulations of KCNQ2 (Fig. 7a and Extended Data Fig. 8b). This significant difference between ALS cases and controls was quantified by measuring KCNQ2 signal intensity variation across all cases and controls (Fig. 7b). Notably, these KCNQ2 accumulations exhibited substantial overlap with ubiquitin B, suggesting that a significant proportion of KCNQ2 in diseased neurons is likely aggregated (Fig. 7c and Extended Data Fig. 8c,d). To increase the confidence in our findings, we evaluated KCNQ2 in lumbar spinal cord sections of an expanded set of 15 ALS cases (n = 11 patients with sporadic ALS and n = 4 cases of C9orf72 familial ALS) and three non-neurological controls in experiments conducted independently at Columbia University (Supplementary Table 5). Analysis of large neurons found in the ventral horn showed that KCNQ2 was also substantially altered in this cohort of patients with ALS. We specifically found that KCNQ2 intensity was significantly higher in the neurons of patients with ALS than it was in controls (Fig. 7d and Extended Data Fig. 8e–g), and we also observed increased focal accumulations that were independent of increased KCNQ2 expression (Fig. 7d,e and Extended Data Fig. 8e,f) and overlapped with ubiquitin B (Extended Data Fig. 8h), mirroring our original observations at Northwestern University. These alterations were consistent across familial and sporadic cases as well as across genetic subtypes (Fig. 7f). Finally, we note that in ALS MNs, KCNQ2 co-stained with the luminal ER marker GRP78 (Fig. 7g), suggesting that the focal KCNQ2 accumulations in patients with ALS are within the ER, as we observed in in vitro human neurons expressing 100% KCNQ2∆E5 protein. Intriguingly, although there was no clear separation in the levels of KCNQ2 accumulation between neurons with or without pathological pTDP-43 (Fig. 7h,i and Extended Data Fig. 8e,f), in some instances, we observed dramatic co-aggregation of KCNQ2 with pTDP-43 cytoplasmic aggregates (Fig. 7h). These experiments do not confirm that the accumulated KCNQ2 protein in tissue from ALS patients was derived from mis-spliced transcript. However, they demonstrate that at this terminal disease stage, there is substantial focal accumulation and ubiquitination of total KCNQ2 protein, perhaps as a result of the dominant negative effects of KCNQ2∆E5 protein on the trafficking of the WT isoform that we observed in vitro.

a–c, Samples analyzed at Northwestern University (NU cohort). a, Immunohistochemistry of neurons from non-neurological control (n = 3) and sporadic ALS (sALS) (n = 3) spinal cord sections stained for DAPI (blue), MAP2 (white), KCNQ2 (green) and TDP-43 (red). b, KCNQ2 signal intensity variation was significantly higher in sALS cases: controls, (1) n = 25, (2) n = 21, (3) n = 14; sALS, (1) n = 19, (2) n = 20, (3) n = 30. Data are shown as coefficients of variation (mean-normalized standard deviation); each circle represents one neuron. c, Neurons stained for DAPI (blue), MAP2 (white), KCNQ2 (green) and ubiquitin (red). The square box denotes the magnified region shown at the bottom. Scale bar, 10 μm. d–i, Samples analyzed at Columbia University (CU cohort). d, Immunohistochemistry of MNs from non-neurological control and ALS lumbar spinal cord sections stained for DAPI (blue), KCNQ2 (green) and pTDP-43 (red). e, KCNQ2 signal intensity variation was significantly higher in ALS cases: controls, n = 29 neurons from three individuals; ALS, n = 142 neurons from 15 patients. f, KCNQ2 signal intensity variation was significantly higher in C9orf72 repeat expansion and sALS cases: controls, n = 29 neurons from three individuals; C9orf72, n = 40 from four patients; sALS, n = 102 from 11 patients. g, Neurons stained for DAPI (blue), KCNQ2 (green) and GRP78 (orange). h, sALS neurons from spinal cord sections stained for DAPI (blue), KCNQ2 (green) and pTDP-43 (red). Representative cases of localization of KCNQ2 in large globular pTDP-43 aggregates. i, KCNQ2 signal intensity variation was significantly higher in neurons from ALS patients, irrespective of pTDP-43 pathology: control, n = 29; ALS without TDP-43 pathology, n = 86; ALS with TDP-43 pathology, n = 56. P values in b and e determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction; in f and i by Brown–Forsythe and Welch ANOVA test followed by Benjamini and Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. Scale bars for NU, 10 μm; for CU, 15 μm. Detailed sample information is included in Supplementary Table 5.

Discussion

The functional implications of TDP-43 pathophysiology in human MNs has been intensely investigated since it was identified in ubiquitinated aggregates of postmortem brains from individuals affected with ALS and FTD61. Here, we find that TDP-43 dysfunction yields altered KCNQ2 mRNA that escapes degradation and is translated into a non-functional neoprotein without current conduction capacity that causes inherent hyperexcitability in neurons. This de novo protein variant can accumulate in the ER of neurons, inhibit the trafficking of WT KCNQ2 to the membrane and likely contributes to MN hyperexcitability described in patients with ALS/FTD.

The mis-splicing of KCNQ2 represents a spurious, TDP-43-dependent event. We observed it in transcriptomes of stem cell-derived spinal-like cholinergic MNs and cortical-like glutamatergic neurons in vitro as well as in the spinal cord and motor cortex of tissue from patients with ALS. We detected KCNQ2∆E5 in sporadic and familial ALS with known predisposition for TDP-43 aggregation, whereas it was not detected in neurological controls or typically non-TDP-43 ALS cases, such as those with SOD1 mutations. At present, there is a paucity of reliable biomarkers for the diagnosis of ALS. Our data suggest that KCNQ2∆E5, which is absent in neurotypical individuals and abundant in patients with ALS and FTD-TDP, is a potential molecular biomarker of TDP-43 dysfunction. Indeed, recent work demonstrated that the KCNQ2∆E5 neoprotein can be detected using mass spectrometry in cerebrospinal fluid samples from patients with ALS/FTD spectrum disorders62.

TDP-43 has hundreds of RNA targets in the nervous system45,63, is required for regulated alternative splicing and is known to serve both as a splicing repressor and enhancer. To date, there has been a strong focus on studying splicing events that are derepressed upon TDP-43 loss, particularly non-conserved cryptic exons, which lead to dramatic loss of protein or the expression of neopeptides that can be useful as biomarkers62. KCNQ2 mis-splicing differs from such events, as exon 5 is deeply conserved and constitutively included in mRNA in the CNS and is therefore neither an alternatively spliced locus nor a cryptic exon. Nevertheless, like some other TDP-43-regulated cryptic exons, our analysis demonstrates that KCNQ2∆E5 is not conserved in mice. Murine CNS cells lack the UG repeat element that is possibly critical for TDP-43 recruitment, and do not rely on TDP-43 for correct pre-mRNA processing. Interestingly, mouse models based on the artificial nuclear translocation of TDP-43 have revealed cortical hyperexcitability31,32, and the precise mechanism of these effects has not been well-defined. The lack of conservation in KCNQ2 splicing is similarly observed for other TDP-43 target genes, such as STMN2 (refs. 11,12) and UNC13A9,10, suggesting evolutionarily divergent mechanisms for regulating these genes in neurons. It also underscores a need for the development of humanized mouse models64 to evaluate the significance of TDP-43 pathophysiological mechanisms in the context of an intact nervous system65.

Examination of neuronal nuclei with decreased TDP-43 abundance41 revealed that at least 50% of total KCNQ2 may be mis-spliced in affected cells. This is probably an underestimation, as it is based on bulk RNA-seq and may reflect a range of mis-spliced KCNQ2 within individual neurons (0–100% mis-splicing), depending on the degree of TDP-43 pathology within the neuronal population. The application of single-cell technologies and long-read sequencing will illuminate the precise extent and diversity of misprocessed KCNQ2 transcripts within the CNS. Notably, the dominant negative trafficking effects of KCNQ2∆E5 we identified here, as well as the prominent aggregation of KCNQ2 in patient tissue, suggest that KCNQ2 channel dysfunction may be pronounced, at least at the terminal stages of the disease.

Although TDP-43 is undoubtedly critical for the health of MNs, questions that remain unanswered involve determining which of the many transcripts regulated by TDP-43 control important neuronal pathways that are altered in patients with ALS, which of those are related to the origins of the disease and which hold the most promise as therapeutic targets. KCNQ2 channels mediate the repolarizing M-current, which activates to dampen neuronal excitability and limits repetitive firing following bursts of APs. Mutations in this gene can cause epileptic syndromes46,47,66. Our findings, that misprocessed KCNQ2 results in a non-functional protein—effectively a ‘dead’ channel—and causes intrinsic hyperexcitability and striking alterations in the distribution of spiking in human neurons have strong implications for patients with ALS and FTD-TDP. We recently showed that cortical neurons with a heterozygous loss-of-function mutation in KCNQ2 associated with DEE exhibited a dyshomeostatic adaptation that caused an increased burst firing pattern39. The bursting phenotype we observed in KCNQ2∆E5 neurons is highly similar. Although seizures are not typically seen in patients with ALS, neuronal hyperexcitability is a broadly observed feature in both familial and sporadic disease16,17,18,19. As TDP-43 loss-of-function effects are both gradual and heterogeneous within the CNS, mis-splicing of KCNQ2 would not be expected to cause spontaneous epileptic seizures but could lead to focal disruptions in neuronal firing. Furthermore, TDP-43 mis-splicing of other targets involved in synaptic communication, such as UNC13A60, may also lead to synaptic deficits that prevent network-wide epileptiform activity, despite individual neurons being inherently hyperexcitable.

Our findings provide a direct mechanistic link between TDP-43 dysfunction and decreased neuronal M-currents that are probably contributing to the cortical hyperexcitability seen in patients. Intriguingly, the anticonvulsant ezogabine, which had been evaluated in clinical trials as a treatment for ALS38, augments KCNQ2-5 channel-encoded current amplitudes67,68. Given that the degree of hyperexcitability may be prognostic of ALS disease progression and survival23,24, correction of mis-spliced KCNQ2∆E5 may be an attractive therapeutic target for ALS. Pharmacological strategies aimed at restoring M-current levels may not stem the tide of Kv7.2 activation, given some of the dominant negative trafficking effects of the mis-spliced protein. smASOs like the ones we developed here constitute an alternative therapeutic strategy, as they would selectively increase functional Kv7.2 activity in the most affected neurons with TDP-43 pathology.

Importantly, several of our key findings—including the electrophysiological characterization of TDP-43-depleted neurons, the beneficial effects of the KCNQ2 smASO on excitability and the histopathological characterization of KCNQ2 in ALS postmortem tissue—were verified across two independent laboratories. These experiments—performed using different iPS cell-model systems and patient tissues, operators and reagents—serve as strong proof of the robustness and reproducibility of our observations. At the same time, our work has some limitations, primarily associated with the lack of our ability to study mis-spliced KCNQ2 over the course of disease progression in an appropriate in vivo model, as well as in neurons derived from sporadic and familial ALS iPS cells. Notably, such longitudinal assessment is also difficult in the clinical field, for which interpretation of threshold-tracking transcranial magnetic stimulation (TT-TMS) and short-interval intracortical inhibition measurements of axonal and neuronal excitability are confounded by progressive neuronal loss. Unfortunately, the lack of spontaneous pathological TDP-43 phenotypes such as nuclear depletion or cytoplasmic aggregation in iPS cell-derived neurons69, probably because of their embryonic nature70, constitutes a major bottleneck in the field. Notably, recent findings using iPS cell-derived neurons with ALS-associated TDP-43 mutations highlighted excitability alterations and structural changes in the AIS29, which is the site of the highest density of KCNQ2 channels. Although TDP-43 KD does not emulate potential gain-of-function effects driven by TDP-43 aggregation, it is able to capture key molecular defects that are seen in patients with ALS71,72.

Our observation of the cytosolic accumulation of KCNQ2∆E5 is an unexpected consequence of KCNQ2 misprocessing that underscores the prioritization of examining precise splice variants instead of genetic loss-of-function to study TDP-43 targets. It underscores a direct link between proteotoxic stress and neuronal hyperexcitability acting downstream of TDP-43 dysfunction in patients with ALS and FTD-TDP. Lastly, we note the possibility that the de novo KCNQ2∆E5 variant may trigger autoimmune deregulation, constituting another collateral effect of TDP-43 dysfunction that may be contributing to ALS pathophysiology.

Methods

Transcriptomic datasets

We obtained the following published datasets from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus or the European Nucleotide Archive: FACS-purified MNs depleted of TDP-43: Eggan lab11, GSE121569; purified TDP-43-high and TDP-43-low neuronal nuclei datasets: Lee lab41, GSE126543 (we used six out seven datasets with sufficient read coverage for KCNQ2); i3Neurons, SH-SY5Y and SK-N-DZa TDP-43 depleted datasets: Fratta lab9, PRJEB42763; and mouse TDP-43 depletion studies: Cleveland lab45, GSE27394. Raw sequencing data were mapped to the human reference genome sequence (GRCh38.p13) using HISAT2 (ref. 73). The raw reads for TDP-43 iCLIP from SH-SY5Y cells published by the Fratta lab (E-MTAB-10297) were mapped using bowtie with parameters -a -l 10 -m 1 -v 1. We obtained 1,124 RNA-seq datasets from the Target ALS/New York Genome Center ALS Consortium, consisting of de-identified postmortem brain samples from CNS tissues; we mapped fastq files to the human reference genome sequence (GRCh38.p13) using HISAT2 (ref. 73). Differential gene expression analyses were done using the DESeq2 (ref. 74) package in R.

Detection of KCNQ2, STMN2 and UNC13A mis-splicing in postmortem RNA-seq datasets

A custom script was used to count reads that indicate mis-splicing. In brief, we filtered the BAM files to only include unique, high-quality mapped reads using Samtools (v.1.18)75. We mined these files to identify split reads that mapped across junctions of interest with no mismatches and with at least 15 nucleotides mapped across each side of the junction. We used the ‘subject group’ metadata provided by the New York Genome Center to assign sample IDs to control, ALS or other neurological disease. We stratified samples into sporadic, C9orf72 or non-TDP-43 using ‘reported genomic mutations from sites’.

Splicing analysis

Splice junctions were mapped using the MAJIQ algorithm (v.2.0) under default conditions40. Splice graphs and known or novel local splice variants were defined through the use of the MAJIQ builder provided with comprehensive human gene annotations (GENCODE release 36: GRCh38.p13) and uniquely mapped BAM files as input. The MAJIQ Quantifier was used to calculate relative abundances (percent selected index) for all defined junctions from the perspective of sources and targets40. Following this step, the MAJIQ dPSI function was used to compare different conditions, and the Voila methods outputted the results into tabular formats containing local splice variants that underwent significant changes between specified conditions. Custom R scripts were written to process all significant local splice variants to obtain significantly changing splice junctions. We used probability changing > 0.8 and mean_dpsi_per_lsv_junction > 0.1. These criteria provided junctions with a strong statistical likelihood of at least a 10% change between conditions. MAJIQ also defined de novo junctions based on the provided GENCODE annotations. We adopted a more stringent definition in which de novo junctions were required to have a PSI < 0.05 in control conditions. This allowed us to distinguish de novo splicing that was caused by poor annotation of human neurons versus those that are repressed by TDP-43. Sashimi plots were generated using Integrative Genomics Viewer76.

Cell culture

Stem cells at Northwestern University were maintained on plates coated with Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning, CLS354234) in mTeSR or mTeSR Plus media (StemCell Technologies, 100-0276) and passaged with Accutase (Gibco, A11105). The homozygous KCNQ2∆E5 engineered cell line was created using the WA01 (H1) human embryonic stem cell line from WiCell. The iPS cell lines 18a77 and KOLF2.1J78 were used to differentiate spinal MNs and cortical NGN2-based neurons at Northwestern University.

Halo-TDP-43 iNeurons59 at University College London were derived from a WTC11 background with a doxycycline-inducible NGN2 construct in the AAVS1 safe-harbor locus and a CRISPRi construct in the CLYBL safe-harbor locus60. These were maintained in E8 Flex Medium (Thermo) on Geltrex (Thermo) coated plates and passaged with TrypLE (Thermo) at 80% confluency.

CHO cells expressing human KCNQ3 (CHO-Q3; Kv7.3, GenBank accession no. NM_004519) were generated using Flp-In-CHO cells54. Cells were grown in F-12 nutrient mixture medium (GIBCO/Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (ATLANTA Biologicals), Zeocin (100 μg ml−1), hygromycin B (600 μg ml−1), penicillin (50 U ml−1) and streptomycin (50 μg ml−1).

SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, CRL-2266) were grown in DMEM (Gibco, 11965092) supplemented with 15% FBS (Takara Bio, 631106), GlutaMAX (Gibco, 35050061), penicillin (50 U ml−1) and streptomycin (50 μg ml−1).

Primary glial cell cultures were derived from postnatal day 0–2 CD-1 mice (Charles River). Brain cortices were dissected free of meninges in dissection buffer Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (Thermo Fisher), then digested with trypsin (Thermo Fisher) and DNaseI (Worthington) for 10 min at 37 °C. The tissue was dissociated in glia medium: DMEM (Corning, 15–013-CV) supplemented with GlutaMAX, D-glucose, 10% normal horse serum (Life Technologies) and penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher). After centrifugation and resuspension, cells were filtered through a 0.45 µm cell strainer and plated on poly-D-lysine (PDL)-coated plates with glia media for 2 weeks. Glial cultures were tested for mycoplasma, dissociated for expansion and frozen in 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and horse serum. All animal experiments were approved and conducted in accordance with the policies and guidelines set forth by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC47).

All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All cell lines were regularly tested for the presence of mycoplasma using MycoAlert PLUS Detection Kit (Lonza).

Human stem cell-based neuronal differentiations

Northwestern University

MNs

We used previously described protocols to generate spinal MNs79. In brief, iPS cells were plated in mTESR1 supplemented with 10 μM ROCK inhibitor (DNSK International, Y-27632) at a density of 1.2 million per well of a six-well plate. From the day after plating (day 0) until day 5, the media was replaced daily with 50% DMEM:F-12/50% Neurobasal media, supplemented with non-essential amino acids, GlutaMAX, N2, B27 (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and with 10 μM SB431542 (DNSK International), 100 nM LDN193189 (DNSK International), 1 μM retinoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). From day 6–13, the media was replaced daily with 50% DMEM:F-12/50% Neurobasal media, supplemented with non-essential amino acids, GlutaMAX, N2, B27 (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and with 1 μM retinoic acid, 1 μM SAG, 5 μM DAPT (DNSK International) and 4 μM SU5402 (DNSK International). Cells were dissociated on day 14 using TrypLE (Thermo Fischer Scientific) with added DNaseI (Worthington) and plated onto plates or cover slips previously coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences). A half-media change was performed every 2–3 days with Neurobasal media supplemented with non-essential amino acids, GlutaMAX, N2, B27, 1% FBS and the neurotrophic factors BDNF, CNTF, GDNF (10 ng ml−1, R&D Systems) and ascorbic acid (0.2 μg ml−1). ASOs (5 μM) were added directly to the neuronal maturation media (gymnotic delivery) three times, starting on day 20 after differentiation until electrophysiological experiments were performed.

Excitatory neurons

We used previously described protocols to generate cortical-like excitatory neurons42,43. In brief, stem cells were infected with a cocktail of three lentiviral constructs: TetO-Ngn2-Puro, TetO-GFP and rtTA80. Media was replaced after overnight incubation in mTeSR Plus with 10 μM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632. Cells were passaged and differentiated at 70–80% confluency. On days 1–4, cells were grown in induction media consisting of the following minimal components: DMEM/F-12 (Life Technologies, 11320-033), N2 supplement (0.5% v/v; Gibco, 17502048), 1× GlutaMAX (Gibco, 35050061), 0.1 mM MEM non-essential amino acids (Gibco, 11140050) and 0.5% glucose. Media was changed daily, with the addition of the following small molecules: day 1, 10 mM SB431543 (Custom Synthesis), 200 nM LDN193189 (Custom Synthesis), doxycycline hyclate (2 mg ml−1) and 4 mM XAV939 (Stemgent, 04-00046). Days 2–4, puromycin (5 mg ml−1), 10 mM SB431543, 200 nM LDN193189, doxycycline hyclate (2 mg ml−1) and 4 mM XAV939 (Stemgent, 04-00046). Cells were dissociated on day 4 using Accutase (Gibco, A11105), resuspended in NBM media supplemented with ROCK inhibitor, then mixed 1:1 in 80% Hyclone-FBS/20% DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen until thawed on day 5 for subsequent experiments. NGN2 neurons were initially seeded in neuronally supportive medium described above with the addition of 10 ng ml−1 BDNF (R&D Systems) and supplemented with ROCK inhibitor for the first 24 h. Thereafter, half-media changes were performed every 3 days. For imaging and MEA experiments, neurons were co-cultured with mouse glial cells39.

University College London

Excitatory neurons

Doxycycline-inducible NGN2 overexpression at the AAVS1 safe-harbor locus was used to forward-program human iPS cells into cortical-like neurons. Human iPS cells were passaged using TrypLE into Geltrex-coated plates containing induction media: DMEM/F-12 with GlutaMAX (Thermo), 1× non-essential amino acids (Thermo), 2 μg ml−1 doxycycline hyclate (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 μM XAV939 (Cayman Chemical), 10 μM SB431542 (Cayman Chemical), 100 nM LDN193189 (Cayman Chemical) and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor (Tocris, Y-27632) for the first 24 h. The media was changed daily for 3 days. A total of 500,000 neurons were re-plated onto 18 mm coverslips (Deckglaser) coated with PDL (Gibco) and laminin (Thermo), containing 50,000 primary E18 rat astrocytes81 that were grown in DMEM/F-12 with GlutaMAX, 10% ES-FBS (Thermo) and 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) for 1 week prior. Neuronal and astrocyte co-cultures were subsequently grown in neuronal maturation media containing BrainPhys (StemCell Technologies), 1× non-essential amino acids, 1× GlutaMAX (Gibco), 2% ES-FBS, 1× N21-MAX (R&D Systems), 1× N-2 MAX (R&D Systems), 20 ng ml−1 BDNF (Peprotech), 20 ng ml−1 GDNF (Peprotech), 20 ng ml−1 NT3, 1 mM dibutyryl cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich), 200 nM L-ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μg ml−1 laminin. For the first 24 h, ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 μM) and 1× CultureOne (Gibco) were added to the media. Half-media changes were performed twice each week. Halo-iNeurons were cultured for 2 weeks and then treated with 30 nM HaloPROTAC-E to knock down TDP-43. ASOs (1 μM) were added directly to the neuronal maturation media (gymnotic delivery) at the same time to enable free uptake and were included in all subsequent media changes for another 2 weeks until electrophysiological experiments were performed.

Lentivirus production and transduction

TetO-Ngn2-puro (Addgene plasmid, 52047) and TetO-FUW-EGFP (Addgene plasmid, 30130) plasmids were gifts from M. Wernig80,82. FUW-M2rtTA (Addgene plasmid, 20342) was a gift from R. Jaenisch83. Lentiviruses were generated in HEK293T cells using the second-generation packaging vectors psPAX2 and pMD2.G as described previously39,84 by the Northwestern University DNA/RNA Delivery Core or ALSTEM.

CLIP and RIP