Abstract

Chitin is an essential component of the fungal cell wall. Chitin synthases (Chss) catalyze chitin formation and translocation across the membrane and are targets of antifungal agents, including nikkomycin Z and polyoxin D. Lack of structural insights into the action of these inhibitors on Chs has hampered their further development to the clinic. We present the cryo-EM structures of Chs2 from Candida albicans (CaChs2) in the apo, substrate-bound, nikkomycin Z-bound, and polyoxin D-bound states. CaChs2 adopts a unique domain-swapped dimer configuration where a conserved motif in the domain-swapped region controls enzyme activity. CaChs2 has a dual regulation mechanism where the chitin translocation tunnel is closed by the extracellular gate and plugged by a lipid molecule in the apo state to prevent non-specific leak. Analyses of substrate and inhibitor binding provide insights into the chemical logic of Chs inhibition, which can guide Chs-targeted antifungal development.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The coordinates are deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the PDB IDs 7STL (apo), 7STM (UDP-GlcNAc-bound), 7STN (nikkomycin Z-bound state) and 7STO (polyoxin D-bound state), respectively. The cryo-EM density maps are deposited in EMDB with the IDs EMD-25432 (apo), EMD-25433 (UDP-GlcNAc-bound), EMD-25434 (nikkomycin Z-bound state) and EMD-25435 (polyoxin D-bound state), respectively. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tharanathan, R. N. & Kittur, F. S. Chitin–the undisputed biomolecule of great potential. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 43, 61–87 (2003).

Steinfeld, L., Vafaei, A., Rosner, J. & Merzendorfer, H. Chitin prevalence and function in bacteria, fungi and protists. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1142, 19–59 (2019).

Mahmoud, Y. A., El-Naggar, M. E., Abdel-Megeed, A. & El-Newehy, M. Recent advancements in microbial polysaccharides: synthesis and applications. Polymers (Basel) 13, 4136 (2021).

Mikusova, V. & Mikus, P. Advances in chitosan-based nanoparticles for drug delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5776 (2021).

Bhatt, K. et al. High mortality co-infections of COVID-19 patients: mucormycosis and other fungal infections. Discoveries (Craiova) 9, e126 (2021).

Gangneux, J. P., Bougnoux, M. E., Dannaoui, E., Cornet, M. & Zahar, J. R. Invasive fungal diseases during COVID-19: We should be prepared. J. Mycol. Med. 30, 100971 (2020).

Marr, K. A. et al. Aspergillosis complicating severe coronavirus disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 18–25 (2021).

Fisher, M. C. et al. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature 484, 186–194 (2012).

Lima, S. L., Colombo, A. L. & de Almeida Junior, J. N. Fungal cell wall: emerging antifungals and drug resistance. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2573 (2019).

Roemer, T. & Krysan, D. J. Antifungal drug development: challenges, unmet clinical needs, and new approaches. Cold. Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, a019703 (2014).

Coutinho, P. M., Deleury, E., Davies, G. J. & Henrissat, B. An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol. 328, 307–317 (2003).

Dorfmueller, H. C., Ferenbach, A. T., Borodkin, V. S. & van Aalten, D. M. F. A structural and biochemical model of processive chitin synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 23020–23028 (2014).

Orlean, P. & Funai, D. Priming and elongation of chitin chains: Implications for chitin synthase mechanism. Cell Surf. 5, 100017 (2019).

Osada, H. Discovery and applications of nucleoside antibiotics beyond polyoxin. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 72, 855–864 (2019).

Nix, D. E., Swezey, R. R., Hector, R. & Galgiani, J. N. Pharmacokinetics of nikkomycin Z after single rising oral doses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 2517–2521 (2009).

Shubitz, L. F., Roy, M. E., Nix, D. E. & Galgiani, J. N. Efficacy of Nikkomycin Z for respiratory coccidioidomycosis in naturally infected dogs. Med. Mycol. 51, 747–754 (2013).

Draelos, M. M. & Yokoyama, K. in Comprehensive Natural Products III (eds Liu, H.-W. & Begley, T. P.) 613–641 (Elsevier, 2020).

Kim, M. K., Park, H. S., Kim, C. H., Park, H. M. & Choi, W. Inhibitory effect of nikkomycin Z on chitin synthases in Candida albicans. Yeast 19, 341–349 (2002).

Kang, M. S. et al. Isolation of chitin synthetase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification of an enzyme by entrapment in the reaction product. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 14966–14972 (1984).

Morgan, J. L., Strumillo, J. & Zimmer, J. Crystallographic snapshot of cellulose synthesis and membrane translocation. Nature 493, 181–186 (2013).

Purushotham, P., Ho, R. & Zimmer, J. Architecture of a catalytically active homotrimeric plant cellulose synthase complex. Science 369, 1089–1094 (2020).

Martinez-Rucobo, F. W., Eckhardt-Strelau, L. & Terwisscha van Scheltinga, A. C. Yeast chitin synthase 2 activity is modulated by proteolysis and phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 417, 547–554 (2009).

Uchida, Y., Shimmi, O., Sudoh, M., Arisawa, M. & Yamada-Okabe, H. Characterization of chitin synthase 2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. II: Both full size and processed enzymes are active for chitin synthesis. J. Biochem. 119, 659–666 (1996).

Nagahashi, S. et al. Characterization of chitin synthase 2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Implication of two highly conserved domains as possible catalytic sites. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13961–13967 (1995).

Morgan, J. L. et al. Observing cellulose biosynthesis and membrane translocation in crystallo. Nature 531, 329–334 (2016).

Cos, T. et al. Molecular analysis of Chs3p participation in chitin synthase III activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 256, 419–426 (1998).

Yabe, T. et al. Mutational analysis of chitin synthase 2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Identification of additional amino acid residues involved in its catalytic activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 258, 941–947 (1998).

Hori, M., Kakiki, K. & Misato, T. Further study on the relation of polyoxin structure to chitin synthetase inhibition. Agric. Biol. Chem. 38, 691–698 (1974).

Jackson, K. E., Pogula, P. K. & Patterson, S. E. Polyoxin and nikkomycin analogs: recent design and synthesis of novel peptidyl nucleosides. Heterocycl. Commun. 19, 375–386 (2013).

Decker, H., Zahner, H., Heitsch, H., Konig, W. A. & Fiedler, H. P. Structure-activity relationships of the nikkomycins. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137, 1805–1813 (1991).

Hori, M., Kakiki, K., Suzuki, S. & Misato, T. Studies on the mode of action of polyoxins: Part III. Relation of polyoxin structure to chitin synthetase inhibition. Agric. Biol. Chem. 35, 1280–1291 (1971).

Shenbagamurthi, P., Smith, H. A., Becker, J. M., Steinfeld, A. & Naider, F. Design of anticandidal agents: synthesis and biological properties of analogs of polyoxin L. J. Med. Chem. 26, 1518–1522 (1983).

Khare, R. K., Becker, J. M. & Naider, F. R. Synthesis and anticandidal properties of polyoxin L analogs containing.alpha.-amino fatty acids. J. Med. Chem. 31, 650–656 (1988).

Lenardon, M. D., Munro, C. A. & Gow, N. A. Chitin synthesis and fungal pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 416–423 (2010).

Gooday, G. W. & Schofield, D. A. Regulation of chitin synthesis during growth of fungal hyphae: the possible participation of membrane stress. Can. J. Bot. 73, 114–121 (1995).

Orlean, P. Two chitin synthases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 5732–5739 (1987).

Grabinska, K. A., Magnelli, P. & Robbins, P. W. Prenylation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Chs4p affects chitin synthase III activity and chitin chain length. Eukaryot. Cell 6, 328–336 (2007).

McManus, J. B., Yang, H., Wilson, L., Kubicki, J. D. & Tien, M. Initiation, elongation, and termination of bacterial cellulose synthesis. ACS Omega 3, 2690–2698 (2018).

Lenardon, M. D., Whitton, R. K., Munro, C. A., Marshall, D. & Gow, N. A. Individual chitin synthase enzymes synthesize microfibrils of differing structure at specific locations in the Candida albicans cell wall. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 1164–1173 (2007).

Vermeulen, C. A. & Wessels, J. G. Chitin biosynthesis by a fungal membrane preparation. Evidence for a transient non-crystalline state of chitin. Eur. J. Biochem. 158, 411–415 (1986).

Li, R. K. & Rinaldi, M. G. In vitro antifungal activity of nikkomycin Z in combination with fluconazole or itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43, 1401–1405 (1999).

Sudoh, M. et al. Identification of a novel inhibitor specific to the fungal chitin synthase. Inhibition of chitin synthase 1 arrests the cell growth, but inhibition of chitin synthase 1 and 2 is lethal in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32901–32905 (2000).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Zhang, K., Gctf & Real-time, C. T. F. determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Punjani, A., Zhang, H. & Fleet, D. J. Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat. Methods 17, 1214–1221 (2020).

Zivanov, J. et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7 (2018).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010).

Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C. & Ferrin, T. E. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. J. Struct. Biol. 157, 281–287 (2007).

Smart, O. S., Neduvelil, J. G., Wang, X., Wallace, B. A. & Sansom, M. S. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 354–60, 376 (1996).

Haig, N. A. et al. Identification of self-lipids presented by CD1c and CD1d proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37692–37701 (2011).

Joyce, L. R. et al. Identification of a novel cationic glycolipid in Streptococcus agalactiae that contributes to brain entry and meningitis. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001555 (2022).

Acknowledgments

Cryo-EM data were screened and collected at the Duke University Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (SMIF), the Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM (PNCC) in OHSU, and the UNC CryoEM core facility. We thank N. Bhattacharya at SMIF, J. Myers at PNCC, and J. Peck and J. Strauss of the UNC CryoEM Core Facility for assistance with the microscope operation. We thank A. Stelling for assistance with the FTIR measurements, M. M. Draelos for preparation of nikkomycin Z and J. Fedor for his critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant R01GM115729 (K.Y) and Duke startup funds (S.-Y.L). A portion of this research was supported by NIH grant U24GM129547 and performed at the PNCC at OHSU and accessed through EMSL (grid.436923.9), a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. Duke SMIF is affiliated with the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network, which is in part supported by the NSF (ECCS-2025064). The UNC CryoEM core facility is supported by NIH grant P30CA016086.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.R. conducted biochemical preparation, sample freezing, single-particle 3D reconstruction of the enzyme, crosslinking experiment and ITC experiments under the guidance of S.-Y.L. A.C. carried out enzymatic assays, and the FTIR measurement under the guidance of K.Y. Y.S. and Z.R. collected cryo-EM data. Z.R. and S.-Y.L. performed model building and refinement. Z.G. performed the lipid MS analysis. S.-Y.L, Z.R., K.Y. and A.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

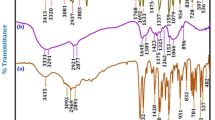

Extended Data Fig. 1 Purification and enzymatic reaction of CaChs2 and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis.

a, Representative gel-filtration profile and SDS-PAGE of purified CaChs2. The experiments have been repeated more than ten times independently with essentially the same results. b, Enzymatic reaction of CaChs2. c-e. Representative ITC data of CaChs2 WT (c), W647A (d) and Q643A (e) vs Nikkomycin. The Kd is the average of three independent repeats. The uncropped gel image for a is available as source data.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Cryo-EM analysis of CaChs2 in apo, UDP-GlcNAc bound, nikkomycin Z bound, and polyoxin D bound states.

a, General flowchart for data processing. b, Representative micrographs for each dataset. The number of total micrographs in each dataset is shown in Extended Data Fig.3. c, Representative 2D classes. d, Local resolution maps. e, Euler angle distribution of the final reconstructions. f, The gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curves for the final reconstructions. g, FSC curves of the refined models versus the corresponding full map (red) and half maps (green and blue).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Data processing flowchart.

Data processing for CaChs2 in apo (a), UDP-GlcNAc bound (b), nikkomycin Z bound (c), and polyoxin D bound (d) states.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Representative EM densities.

Representative densities for CaChs2 in apo (a), UDP-GlcNAc bound (b), nikkomycin Z bound (c), and polyoxin D bound (d) states.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparison of architectures of chitin synthase CaChs2 and cellulose synthases RsBcsA and PttCesA8.

a, Domain arrangement of CaChs2, RsBcsA and PttCesA8. b-c, Topology diagrams of RsBcsA (b) and PttCesA8 (c).

Extended Data Fig. 6 The dimer interface of CaChs2.

a, Cartoon representation of a CaChs2 dimer. The dimer interface is highlighted in the rectangle. b-c, Close-up view of the dimer interface in two orientations.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Structural comparison of polymer translocation tunnels and substrate binding sites of CaChs2, RsBcsA and PttCesA8.

a, Left: Ribbon representation of RsBcsA in the product bound state (PDB code: 5EJZ) with the tunnel highlighted in surface representation and the cellulose polymer in sticks. Trp383, which defines the intracellular entry of the tunnel is highlighted in sticks. Right: Length and radius of the tunnel calculated by the HOLE program. b. Ribbon representation of PttCesA (PDB code: 6WLB) with the tunnel highlighted in surface representation and the cellulose polymer in sticks. Trp718, which defines the intracellular entry of the tunnel is highlighted in sticks. Right: Length and radius of the tunnel calculated by the HOLE program. c-d. Overlay of the substrate binding sites of CaChs2 (green) and substrate-bound RsBcsA (orange) (PDB code: 5EIY). Conserved residues that interact with the substrates and the catalytic residues are shown as sticks. e-f. Overlay of binding sites of CaChs2 (green) and product-bound PttCesA8 (purple) (PDB code: 6WLB). Conserved residues that interact with the substrates and the catalytic residues are shown as sticks.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Conservation mapping of CaChs2 and EM density of UDP-GlcNAc and Mg2+ at the substrate binding site.

a, Cross-section surface representation of a CaChs2 monomer bound to nikkomycin Z (yellow spheres). b, Detailed interactions between CaChs2 and nikkomycin Z. In both a and b, CaChs2 is colored based on the conservation score calculated by the Consurf Server (https://consurf.tau.ac.il/) from 150 Chs homologs whose sequence identity varies from 35% to 99%. Conservation scores: 1, ~15% conserved; 5, ~60% conserved; 9, 100% conserved. c-d, Density (Threshold = 0.007) of within 6 Å of UDP-GlcNAc, Mg2+, and residues interacting with the substrate, viewed from two orientations, is shown as grey surfaces. The protein model is shown as cartoon and the substrate and residues at the binding site are shown as sticks. The map and model of residues obstructing the view are hidden for clarity.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Identification of lipids copurified with CaChs2 by LC/MS.

a, Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of normal phase LC/MS of lipids extracted from the CaChs2 protein sample. b, Representative chemical structure of ceramide and mass spectrum of the 2.88 min TIC peak in a showing the chloride adduct [M + Cl]- ions of ceramide species. c, Representative chemical structure of and mass spectrum of the 16.20 min TIC peak in a showing the [M-H]- ions of PE molecular species. This identification of ceramide and PE was supported by exact mass measurement and MS/MS. The TIC peaks at 14.09, 21.16 and 27.18 min are consistent with glycodiosgenins (GDN) containing two, three and four sugars whose [M + Cl]- ions are observed at m/z 875.5, 1037.5 and 1199.5, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Map and model of the domain-swapped region and crosslinking experiments to validate the domain-swapped assembly.

a-b, Unsharpened map of the domain-swapped region of UDP-GlcNAc bound CaChs2 shown at threshold 0.00475, viewed from two orientations. c. Representative density of the domain-swapped region. The protein model is shown as cartoon and side chains are shown as sticks. Some of the side chains are not built due to lack of signal. d. CaChs2 viewed from the intracellular side. The Cα atom of P906 and N917, which define the N and C-terminus of the loop between H10 and TM5, are shown as spheres. The distances from the Cα of P906 to that of N917 within the same monomer or in different monomers are labeled with dashed lines. It is noteworthy that the distance between P906 and N917 is closer in the domain swapped arrangement (30 Å) than the non-domain swapped arrangement (46.5 Å). Because the length of an amino acid in a linear chain is ~3.5 Å, non-domain swapped configuration is physically impossible. e. Model of CaChs2 dimer with one protomer in blue and the other in salmon. Cα atoms of residues where cysteine was introduced are shown as spheres. The crosslinking cysteine pairs are labeled with dashed lines. f. SDS-PAGE analysis of single and double cysteine mutants of CaChs2. The experiment has been repeated four times from two biological repeats with essentially the same results. Uncropped gel images for f are available as source data.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Table 1.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Uncropped gel for 1a.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Uncropped gels for 10f.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, Z., Chhetri, A., Guan, Z. et al. Structural basis for inhibition and regulation of a chitin synthase from Candida albicans. Nat Struct Mol Biol 29, 653–664 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-022-00791-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-022-00791-x

This article is cited by

-

Effective treatment of systemic candidiasis by synergistic targeting of cell wall synthesis

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Molecular landscape of the fungal plasma membrane and implications for antifungal action

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Structural insights into translocation and tailored synthesis of hyaluronan

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2025)

-

Molecular basis of neurosteroid and anticonvulsant regulation of TRPM3

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2025)

-

Exploring fungal survival mechanisms: toward next-generation antifungal therapies against Candida spp.

Archives of Microbiology (2025)