Abstract

Anisarchus medius (Reinhardt, 1837) is a widely distributed Arctic fish, serving as an indicator of climate change impacts on coastal Arctic ecosystems. This study presents a chromosome-level genome assembly for A. medius using PacBio sequencing and Hi-C technology. The PacBio assembly totaled 739.07 Mb across 697 contigs, with a Contig N50 of 10.004 Mb. Hi-C mapping yielded 23 chromosomes, with a successful mapping rate of 90.53% and a Scaffold N50 of 30.20 Mb. Genome BUSCO integrity was 97.05%. Repetitive sequences accounted for 240.83 Mb (32.58%) of the genome. Non-coding RNA annotations included 4,928 rRNAs, 9,663 tRNAs, 347 snRNAs, and 21 snoRNAs. A total of 30,345 protein-coding genes were identified, encoding 46,603 proteins, with a BUSCO completeness of 94.98%. Molecular pathway related to the endocrine system, carbohydrate metabolism, folding, sorting, and degradation, signal transduction, and transport and catabolism contribute to A. medius adaptation to extreme Arctic environments. This high-quality genome provides valuable genetic resources for understanding Arctic adaptations and supporting polar ecological conservation and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Anisarchus medius, commonly known as stout eelblenny, is a ray-fin fish that belongs to the eel pricklebacks, taxonomically classified under Order Perciformes, Suborder Cottioidei, Infraorder Zoarcales, and Family Stichaeidae (NCBI: txid980385, Fig. 1). A. medius is a common seen species in the Arctic Ocean, with a practically circumpolar distribution and particular abundance in the Pacific Arctic1. Thriving in muddy substrates at depths of 30–100 m1 and favoring water temperatures below 0 °C2,3, this benthic fish primarily feeds on polychaetes and other small benthic organisms1,4, acting as a critical intermediary in transferring energy from lower benthic trophic levels to higher predators4. By maintaining ecosystem stability, A. medius plays an essential role in Arctic marine food webs1,4. Given the Arctic ecosystem is highly sensitive to climate change, with rising temperatures and shifting ice dynamics threatening its biodiversity5,6,7, A. medius has emerged as an important indicator species for assessing the climate change on population dynamics within the coastal Arctic ecosystems2. Deciphering the high-quality genome of the ecosystem indicator species like A. medius is critical for informing future conservation and management strategies in the face of a rapidly warming climate.

Despite its ecological importance, research on A. medius remains limited and predominantly focused on fundamental aspects, including morphological classification, growth and development, geographical distribution, phylogeny, nutrient composition, and ecological and climatic studies. Morphological studies address characteristics such as body size, age description1,8,9, and skeletal development during ontogenesis10. Growth and development studies have explored various life stages, including egg, larval, post-larval, and juvenile phases1,10,11. Geographical distribution surveys1,9 and phylogenetic research based on mitochondrial genomes and conserved sequences 2,12 have also been conducted. Physiological studies are scarce and mainly focus on the aspect such as fatty acid composition13,14. Key biological questions, such as the reproductive habits and life history of A. medius, remain unanswered. Ecological and climatic studies of A. medius are relatively more abundant, primarily addressing temperature-related phenomena, such as osmotic and ionic regulation at varying temperatures15 and population migrations driven by global warming16,17,18,19. Genomic resources for A. medius are currently limited to one mitochondrial genome2 and two genomic Illumina sequencing datasets20. Critical gaps in understanding the origin, evolution, and adaptive mechanisms of A. medius to the Arctic environment, as well as its conservation and management, highlight the urgent need for high-quality genome sequencing.

This study combines PacBio long-read sequencing with high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology to construct a high-quality, chromosome-level reference genome for A. medius. Comprehensive genomic annotation includes repetitive sequences, non-coding elements, and protein-coding genes. Functional annotation, including Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis, further enriches our understanding of the A. medius genome. These findings provide valuable insights into the adaptive evolution of Arctic organisms and establish a foundation for polar ecological conservation and management efforts.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal handling and experimental procedures were approved by the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University Ethics Committee (approval number: PZCASFAFU24069).

Sample collection and sequencing

During the 2014 Chinese Arctic Research Expedition, A Stout Eelblenny (A. medius) was sampled aboard by the icebreaker R/V Xuelong (Snow Dragon) in the Chukchi Sea (-169.02 °W; 67.68°N) through trawling. The arctic fish sample was rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen on the deck and then transferred to a −80 °C freezer for storage21,22,23,24,25. Upon returning to the laboratory, the dorsal muscle tissue of the fish was collected for genomic sequencing and analysis21. High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from the dorsal muscle tissue using QIAGEN Genomic-tip 100/G kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany)22. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, DE, USA), measuring the OD260/280 and OD260/230 ratios22,24. The concentration of the genomic DNA was accurately measured using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The integrity of the genomic DNA was verified through 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis21,22,24.

The SMRTbell library was prepared using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences)21,26. In brief, 15 μg of genomic DNA was subjected to an initial enzymatic reaction to remove single-stranded overhangs, followed by treatment with repair enzymes to fix any potential damage to the DNA backbone. Once the DNA damage was repaired, the ends of the double-stranded fragments were polished, and an A-overhang was added. The fragments were then ligated to T-overhang SMRTbell adapters at 20 °C for 60 min. After ligation, the SMRTbell library was purified using 1X AMPure PB beads. The library’s size distribution and concentration were evaluated using a FEMTO Pulse automated pulsed-field capillary electrophoresis instrument (Agilent Technologies, DE, USA) and a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA). Once the library characterization was complete, 3 μg of the library underwent size selection using the BluePippin system (Sage Science, MA, USA), which removed SMRTbells smaller than 15 kb. After size selection, the library was again purified with 1X AMPure PB beads. The final library size and quantity were verified using the FEMTO Pulse and the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit. Sequencing primer and Sequel II DNA Polymerase were then annealed and bound to the SMRTbell library. The library was loaded at an on-plate concentration of 120 pM using diffusion loading. SMRT sequencing was conducted on a single 8 M SMRT Cell using the Sequel II System and the Sequel II Sequencing Kit, with 1800-minute movies produced by Frasergen Bioinformatics Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China), and the resulting data was processed using SMRT LINK 5.0 software26.

Genome assembly and analysis

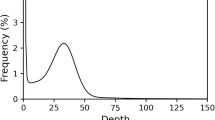

SMRTbell libraries were sequenced on a PacBio Revio system, and consensus HiFi reads were generated using the CCS software (https://github.com/pacificbiosciences/unanimity) with a minimum of three passes (‘-minPasses 3’). To further enhance and validate the assemblies, we generated 35.75 Gb of PacBio HiFi reads for this sample (Table 1), and the length distribution is shown in Fig. 2. These long (~15 kb), highly accurate (>99%) HiFi reads were assembled using Hifiasm (https://github.com/chhylp123/hifiasm)27. To correct errors in the initial assembly, Illumina-derived short reads were employed using Pilon (v1.23)28 for error correction. The final A. medius genome assembly had a total length of approximately 739.07 Mb, consisting of 697 contigs with a Contig N50 of 10.004 Mb (Table 2). The completeness of the assembled genome was assessed using BUSCO (v3.1.0) with the OrthoDB database Actinopterygii_odb929,30, where 97.05% of the BUSCO genes were successfully identified (Fig. 3), indicating a highly complete genome assembly.

To anchor the contigs, 7.39 Gb of clean read pairs were generated from the Hi-C library and mapped to the polished A. medius genome using Bowtie 2 (v2.4.1) with default parameters31. Paired reads, where mates were mapped to different contigs, were utilized for Hi-C-assisted scaffolding. Invalid reads, such as self-ligation, non-ligation, and others like Start Near Rsite, PCR amplification artifacts, random breaks, Large Small Fragments, and Extreme Fragments, were filtered out using the HICUP software32. We clustered 390 contigs into 23 groups using agglomerative hierarchical clustering within 3D-DNA, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The 3D-DNA tool was also employed to order and orient these clustered contigs33,34. A total of 285 contigs, spanning 669,270,049 base pairs, were successfully ordered and oriented. This effort resulted in the first chromosomal-level high-quality assembly, with chromosome lengths ranging from 17.25 Mb to 46.97 Mb, accounting for 90.53% of the total genome sequence (Table 2). The statistics of A. medius chromosome lengths are summarized in Table 3.

Repetitive sequence annotation and analysis

To identify the repeat elements in A. medius genome, we applied two complementary methods: homology-based and de novo prediction. For the homology-based approach, we used RepeatMasker (v4.0.9)35 with the Repbase TE library to identify known transposable elements (TEs). In parallel, we constructed a de novo repeat library for the A. medius genome using RepeatModeler (http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/)36, which automatically integrates two key de novo repeat-finding tools: RECON (v1.08) and RepeatScout (v1.0.5). These tools enabled comprehensive identification, refinement, and classification of consensus models for potential interspersed repeats37. Additionally, a de novo search for long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons was conducted using LTR_FINDER (v1.0.7), LTR harvest (v1.5.11), and LTR retriever (v2.7)38,39,40. We also identified tandem repeats using the Tandem Repeat Finder (TRF) package and simple sequence repeats (SSR) using MISA (v1.0)41. Finally, we merged the libraries generated from both approaches and used RepeatMasker35 to identify the complete repeat content in the genome. As a result, we identified 240.83 Mb of repeat sequences within A. medius genome. A summary of these repeat sequence statistics is provided in Table 4. Furthermore, The Circos program42 was used to generate a circular genome map, displaying various genomic features in concentric layers. From the outermost to the innermost ring, the map illustrates the following: gene density (using a 200 kb sliding window), transposon density (200 kb sliding window), repetitive sequence density (marked as SimpleRepeat by RepeatMasker, with a 200 kb window), and GC content (200 kb sliding window, where red indicates regions with higher GC content than the genome average, and green indicates regions with lower GC content), the innermost ring represents collinear blocks (Fig. 5).

The genomic circus plot of A. medius. The rings, from the outermost to the innermost ring, the map illustrates the following: gene density (using a 200 kb sliding window), transposon density (200 kb sliding window), repetitive sequence density (marked as SimpleRepeat by RepeatMasker, with a 200 kb window), and GC content (200 kb sliding window, where red indicates regions with higher GC content than the genome average, and green indicates regions with lower GC content), the innermost ring represents collinear blocks.

Non-coding annotation and analysis

We employed the tRNAscan-SE (v1.3.1)43 algorithm with default parameters to identify tRNA genes. tRNAs are adaptor molecules composed of RNA that play a crucial role in translating the three-letter genetic code in messenger RNA (mRNA) into the twenty-letter code of amino acids in proteins. For rRNA gene identification, we used RNAmmer (v1.2)44 with the parameters ‘-S euk -m lsu,ssu,tsu’. Additionally, snoRNAs, a class of small RNA molecules that guide the chemical modification of other RNAs (primarily ribosomal RNAs, transfer RNAs, and small nuclear RNAs), were identified using cmscan (v1.1.2)45 against the Rfam (v14.0)46 database with default parameters. In the rRNA analysis, we identified a total of 4,928 rRNA sequences, with lengths ranging from 9,028 bp to 491,254 bp (Table 5). For tRNAs, 9,663 sequences were identified, with a total length of 728,112 bp and an average length of 75 bp, accounting for 0.0011 of the genomes. Additionally, we identified 347 snRNAs and 21 snoRNAs, with total lengths of 45,796 bp and 2,661 bp, respectively.

Protein coding gene prediction and analysis

For protein-coding genes prediction in A. medius genome using three complementary methods: ab initio gene prediction, homology-based prediction, and RNA-Seq-guided prediction. Before gene prediction, the assembled A. medius genome underwent both hard and soft masking with RepeatMasker35 to eliminate repetitive elements. For ab initio gene prediction, we used Augustus (v3.3.3)47,48, which was trained with high-quality protein models generated from RNA-Seq data. For homology-based gene prediction, we employed MAKER (v2.31.10)49. In this process, protein and transcript sequences were aligned to the genome assembly, and coding genes were predicted using the default parameters in MAKER. RNA-Seq-guided gene prediction involved aligning clean RNA-Seq reads to the genome using HISAT2 (v2.0.0)50. The gene structures were then reconstructed using Trinity (v2.3.2)51 with the parameter ‘–genome_guided_bam XXX_aligned.bam’, followed by TransDecoder (v2.01) and MAKER49 to further refine the gene models. Finally, the gene prediction results from the three methods were integrated using EVidenceModeler (EVM, v1.1.1)52, resulting in a consistent set of non-overlapping sequence assemblies that defined the gene structures. In total, 30,345 protein-coding genes were predicted, with an average gene length of 8,563.51 bp. Additionally, 46,603 proteins were identified, with a total length of 23,509,360 amino acids (aa) and an average length of 504.46 aa. Figure 6A illustrates the protein length distribution for the A. medius genome. The completeness of the predicted protein-coding genes was assessed using BUSCO, with the Actinopterygii odb9 database29,30, and the protein-coding genes datasets showed a 94.98% completeness score (Fig. 6B).

The protein-coding gene and protein Busco analysis for the sample of A. medius. (A) The protein length distribution. (B) The protein-coding gene BUSCO assessment for A. medius genome. Indicator: C, indicates complete BUSCOs; S, single-copy BUSCOs; D, complete and duplicated BUSCOs; F, fragmented BUSCOs; and M, missing BUSCOs; n, total number of BUSCO groups analyzed.

Protein coding gene annotation and analysis

Gene functions were predicted by aligning sequences to several major protein databases, including the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Non-Redundant (NR), TrEMBL, InterPro53, and Swiss-Prot54, using BLASTP (ncbi-blast v2.6.0+)55 with an E-value threshold of 1E−5. Additionally, functional annotation was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database56. Protein domain identification was carried out using PfamScan57 and InterProScan (v5.35–74.0)58, with reference to the InterPro protein database53. Motifs and domains within gene models were identified through the PFAM database59. Gene Ontology (GO) terms60 were assigned to each gene using Blast2GO61. In total, approximately 45,380 (about 97.38%) of the predicted protein-coding genes in A. medius were successfully annotated with known gene functions, conserved domains, and GO terms. Table 6 provides a summary of the annotation statistics across the seven major databases.

In the GO annotation, the molecular function category showed the highest rate of annotations for binding (57.75%), followed by catalytic activity (28.28%). In the cellular component category, membrane parts had the most annotations (42.82%), followed by cell parts (21.12%). For the biological process category, metabolic processes (31.10%) and cellular processes (20.59%) were the top two with the highest annotation rates (Fig. 7). In the KEGG annotation, within the organismal systems category, the endocrine system had the highest number of annotated genes (4,368), followed by the immune system (3,291) and nervous system (3,075). Carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, and amino acid metabolism also showed a significant number of annotated genes, with 1,510, 1,300, and 980 genes, respectively. In the genetic information processing category, folding, sorting, and degradation were associated with 959 genes, while translation had 870 annotated genes. For environmental information processing, 10,047 genes were annotated under signal transduction, and 1,912 under signaling molecules and interaction. In the cellular processes category, cellular communities-eukaryotes, and transport and catabolism had 2,238 and 1,593 annotated genes, respectively. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the protein-coding gene annotations from the KEGG and KOG databases.

Data Records

All data from A. medius whole-genome project have been submitted to the NCBI SRA database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1176308 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1176308/). Specifically, the genome PacBio sequencing data was deposited at GeneBank (accession SRR31143456)62. The genome Hi-C sequencing data was deposited at GeneBank (accession SRR31715051)63. The RNA PacBio sequencing data was deposited at GeneBank (accession SRR31715464)64. And The RNA BGI sequencing data was deposited at GeneBank (accession SRR31715465)65. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at GenBank under the accession JBJXUX00000000066. Moreover, the assembly of A. medius has been deposited at GenBank under the accession GCA_046127435.1 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_046127435.1/). Concurrently, the final assembly and annotation files of this study are publicly available in FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27368472)67.

Technical Validation

To ensure the accuracy of sequencing data, we performed a series of quality control checks on the samples before proceeding with library construction. First, we assessed the purity of the genomic DNA using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, DE, USA), measuring the OD260/280 and OD260/230 ratios and ensuring that the nucleic acid absorption peaks were normal. Next, the concentration of the genomic DNA was accurately measured using a Qubit fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA), and the Qubit concentration was compared with the Nanodrop concentration to evaluate the sample’s purity. Finally, the integrity of the genomic DNA was verified through electrophoresis. Only after meeting all quality standards were the samples used for library preparation. The completeness of the assembled genome was evaluated using BUSCO (v3.1) analysis with the OrthoDB database. The results showed that 97.05% of the BUSCO genes (Actinopterygii odb9) were successfully identified, indicating a high level of completeness in the assembled genome (Fig. 2).

Code availability

No custom scripts or codes were used in the management and verification of the data sets in this study. All software and pipelines used for data processing were executed according to the manuals and protocols of the bioinformatics software cited above. The specific parameters were described if the default parameters were not applied for data analysis.

References

Mecklenburg, C. W., Lynghammar, A., Johannesen, E., Byrkjedal, I. & Wienerroither, R. M. 2018. Marine Fishes of the Arctic Region. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna. 372–373 (2018).

Liu, K., Lin, H., Wang, J. & Sun, J. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Anisarchus medius (Reinhardt, 1837). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(2), 3973–3974 (2019).

Whitehead, P., Bauchot, M., Hureau, J., Nielsen, J. & Tortonese, E. Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Vol. 3 1126–1129 (Springer, 1986).

McMeans, B. C., Rooney, N., Arts, M. T. & Fisk, A. T. Food web structure of a coastal Arctic marine ecosystem and implications for stability. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 482, 17–28 (2013).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Post, E. et al. Ecological dynamics across the Arctic associated with recent climate change. Science. 325(5946), 1355–1358 (2009).

Johannessen, O. M. & Miles, M. W. Critical vulnerabilities of marine and sea ice–based ecosystems in the high Arctic. Reg. Environ. Change. 11(Suppl 1), 239–248 (2011).

Forster, C. E., Norcross, B. L. & Spies, I. Documenting growth parameters and age in Arctic fish species in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 177 (2020).

Looby, A. et al. Global inventory of species categorized by known underwater sonifery. Sci Data 10, 892 (2023).

Voskoboinikova, O. Skeleton development in ontogenesis of the butterfish Pholis gunnellus, Anisarchus Anisarchus medius, and slender eel blenny Lumpenus fabricii (Zoarcoidei, Perciformes). J Ichthyol 45, 503–512 (2005).

Chiperzak, D., Hopky, G., Lawrence, M., Schmid, D. & Reist, J. Larval and post-larval fish data from the Canadian Beaufort Sea shelf, July to September, 1987. (Fisheries and Oceans Canada Winnipeg MB, 2003).

Turanov, S., Kartavtsev, Y. P. & Zemnukhov, V. Molecular phylogenetic study of several eelpout fishes (Perciformes, Zoarcoidei) from Far Eastern seas on the basis of the nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 1 gene (CO1). Russ. J. Genet. 48, 208–223 (2012).

Dahl, T. M. et al. Fatty acid composition of the blubber in white whales (Delphinapterus leucas). Polar Biol. 23, 401–409 (2000).

Murzina, S. A. et al. Lipid status of the two high latitude fish species, Leptoclinus maculatus and Lumpenus fabricii. Int J Mol Sci. 14, 7048–7060 (2013).

Prosser, C. L., Mackay, W. & Kato, K. Osmotic and ionic concentrations in some Alaskan fish and goldfish from different temperatures. Physiol. Zool. 43, 81–89 (1970).

Lin, L. et al. Composition and distribution of fish species collected during the fourth Chinese National Arctic Research Expedition in 2010. Arctic Research 23, 116 (2012).

Norcross, B. L., Holladay, B. A., Busby, M. S. & Mier, K. L. Demersal and larval fish assemblages in the Chukchi Sea. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 57, 57–70 (2010).

Frainer, A. et al. Climate-driven changes in functional biogeography of Arctic marine fish communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 12202–12207 (2017).

Fu, S. et al. Trophic levels and trophic niches of fish from the Bering Sea and Chukchi Sea. Biodiversity Science 31, 22521 (2023).

Ghezelayagh, A. et al. Prolonged morphological expansion of spiny-rayed fishes following the end-Cretaceous. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 1211–1220 (2022).

Mu, Y. et al. Whole genome sequencing of a snailfish from the Yap Trench (~7,000 m) clarifies the molecular mechanisms underlying adaptation to the deep sea. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009530 (2021).

Liu, R. et al. De novo genome assembly of limpet Bathyacmaea lactea (Gastropoda: Pectinodontidae), the first reference genome of a deep-sea gastropod endemic to cold seeps. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, evaa100 (2021).

Liu, R., Liu, J. & Zhang, H. Positive selection analysis reveals the deep-sea adaptation of a hadal sea cucumber (Paelopatides sp.) to the Mariana Trench. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 39, 266–281 (2021).

Feng, C. et al. The genome of a new anemone species (Actiniaria: Hormathiidae) provides insights into deep-sea adaptation. Deep-Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 170, 103492 (2021).

Ao, J. et al. Genome sequencing of the perciform fish Larimichthys crocea provides insights into molecular and genetic mechanisms of stress adaptation. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005118 (2015).

Flusberg, B. et al. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat Methods 7, 461–465 (2010).

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 540–546 (2019).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS One. 9(11), e112963 (2014).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genomic data quality and beyond. Curr. Protoc. 1(12), e323 (2021).

Kuznetsov, D. et al. OrthoDB v11: annotation of orthologs in the widest sampling of organismal diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D445–51 (2023).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with burrows–wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010).

Wingett, S. et al. HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Res. 4, 1310 (2015).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 16, 1–11 (2015).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 25(1), 4–10 (2009).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler 2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinform. 9, 18 (2008).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U. & Mascher, M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 33(16), 2583–2585 (2017).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19(9), 1639–1645 (2009).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: A Program for Improved Detection of Transfer RNA Genes in Genomic Sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Lagesen, K. et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 3100–8 (2007).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. C. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(D1), D192–200 (2021).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24(5), 637–644 (2008).

Stanke, M., Schöffmann, O., Morgenstern, B. & Waack, S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinformatics. 7, 1–11 (2006).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatic. 12, 491 (2011).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 12(4), 357–60 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protocols. 8(8), 1494–1512 (2013).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7 (2008).

Mitchell, A. et al. The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(D1), D213–21 (2015).

Boeckmann, B. et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31(1), 365–370 (2003).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25(17), 3389–3402 (1997).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(D1), D109–114 (2012).

Mistry, J., Bateman, A. & Finn, R. D. Predicting active site residue annotations in the Pfam database. BMC Bioinformatic. 8, 1–4 (2007).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 30(9), 1236–1240 (2014).

Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(D1), D222–230 (2014).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25(1), 25–29 (2000).

Conesa, A. & Götz, S. Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics. 1, 619832 (2008).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31143456 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31715051 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31715464 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31715465 (2024).

Liu, R. Y. Anisarchus medius, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBJXUX000000000 (2024).

Liu, R. Y. Genome annotations of Anisarchus medius. Figshare dataset https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27368472 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 42276247 and 32202995), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD2401001), and Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2022J01135). We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the captain, crew, and scientific expedition members of the icebreaker R/V Xuelong (Snow Dragon), especially Pengfei Cui from the Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, for their support and cooperation during the 2014 Chinese Arctic Research Expedition. We also appreciate Ke Xing and Jianan Chen for their assistance in sample preservation, genome survey and manuscript revision. Additionally, we are indebted to the Chinese Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research for providing an invaluable platform for academic discussion and exchange.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinhua Chen, Longshan Lin, and Ruoyu Liu conceived of the project; Scientific expedition members of the icebreaker R/V Xuelong (Snow Dragon), especially Pengfei Cui collected the samples; Ruoyu Liu and Yinan Mu preserved the samples. Longshan Lin and Ran Zhang collected photos of this species. Ruoyu Liu and Ziyu Meng extracted the genomic DNA; Ruoyu Liu and Ping Zheng performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript; Ruoyu Liu revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Meng, Z., Mu, Y. et al. Chromosome-level reference genome and annotation of the Arctic fish Anisarchus medius. Sci Data 12, 68 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04419-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04419-9

This article is cited by

-

Chromosome-level genome assembly of an Arctic fish species pale eelpout (Lycodes pallidus)

Scientific Data (2025)