Abstract

Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) is a critical variable in assessing drought conditions and evaluating plant water stress. Gridded products of global and regional VPD are not freely available from satellite remote sensing, model reanalysis, or ground observation datasets. We present two versions of the first gridded VPD product for the Continental US and parts of Northern Mexico and Southern Canada (CONUS+) at a 1 km spatial resolution and daily time step. We derived VPD from Daymet maximum daily temperature and average daily vapor pressure and scale the estimates based on (1) climate determined by the Köppen-Geiger classifications and (2) land cover determined by the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme. Ground-based VPD data from 253 AmeriFlux sites representing different climate and land cover classifications were used to improve the Daymet-derived VPD estimates for every pixel in the CONUS+ grid to produce the final datasets. We evaluated the Daymet-derived VPD against independent observations and reanalysis data. The CONUS+ VPD datasets will aid in investigating disturbances including drought and wildfire, and informing land management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Continental scale droughts are expected to become more frequent as climate change induced increases in surface temperatures lead to atmospheric drying1. Higher surface temperatures and less frequent precipitation during drought drive competition for water between the land surface and the atmosphere2. Reduced precipitation and increased atmospheric demand for water lead to soil moisture anomalies, limiting water available for plant use3. During droughts, water stress can reduce vegetation growth4 and productivity5, minimizing the role of vegetation as a carbon sink6 and diminishing crop yields7. High atmospheric aridity, measured as vapor pressure deficit (VPD), has been shown to be as important as low soil moisture at driving plant water stress8. High VPD has also been associated with drying out vegetation, which then serves as potential fuel for wildfires9. With drought conditions expected to worsen through the 21st century, further attention should be paid to expanding the study of complex biological and ecohydrological responses to increased atmospheric aridity10. To do so, high spatial and temporal resolution datasets of VPD must be available for the scientific community. Here we present the first daily gridded VPD product for the continental United States, including parts of Northern Mexico and Southern Canada (CONUS+).

VPD has been identified as a major factor in driving water fluxes between the land surface and the atmosphere6,11,12, impacting photosynthesis6 and plant growth4. Vegetation growth responds differently to rising VPD depending on plant type and climate13,14. Thus, there is a need to better understand how plants modulate or adapt to changes in atmospheric aridity across gradients of climates and vegetation types. Some plants close their pores, known as stomata, during periods of elevated VPD in order to conserve water and prevent desiccation15 and hydraulic failure16. Under hydraulic failure, plants can no longer exchange water and carbon with the atmosphere, leading to reduced carbon uptake and increased likelihood of plant mortality14,17. Elevated values of atmospheric aridity have been shown to decrease plant growth4 and shutdown stomatal conductance and photosynthesis rates18, indicating carbon assimilation is highly sensitive to changes in VPD.

Elevated VPD is associated with decreases in crop yields10 which can cause billions of dollars in financial losses for the agricultural sector7. In arid regions of Northern China, reductions in wheat, maize, and soybean yields were shown to be more sensitive to changes in VPD than precipitation or temperature19. Similar sensitivities to rising VPD have been shown in crops yields in the Midwestern US5, central Europe20, and northeast Australia21. Lobell et al.5 found that maize and soybean yields in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana have become increasingly sensitive to high VPD, though farmers are combating yield loss with agronomic advances. In Hungary, positive VPD anomalies, which are associated with increasing temperatures, were shown to negatively impact crop yield for winter wheat20. As climate trends point to higher surface temperatures, the detrimental effects of VPD on crop yields are expected to increase22. On the other hand, there is evidence to suggest high VPD may indeed have a positive effect on certain crop yields in fields with sufficient soil moisture due to plant adaptations that increase water-use efficiency23. Moreover, under simulated climate change conditions with projected increases in temperature and carbon dioxide, elevated carbon dioxide levels may offset the detrimental impacts of high VPD on sorghum grain yield by increasing radiation and transpiration efficiency21. Given the uncertainty in crop responses to rising VPD9 in a changing climate, further analyses incorporating daily-scale VPD are needed10.

High VPD has also been associated with the drying of surface fuels24, increasing the risk of wildfire intensity25 and burned area26. Future climate projections indicate much of the global land area is subject to increases in temperature, resulting in changes to precipitation regimes and wildfire risk27. Increases in VPD as a result of the feedback between rising temperature and lack of precipitation are linked to increases in recent wildfire activity in the western US28,29. Even in humid regions like the Pacific Northwest or Southeast, variability in precipitation resulting from climate change increases the likelihood of drought-induced wildfires30,31. Furthermore, high VPD increases wildfire risk in forest biomes around the globe and jeopardizes their roles as carbon sinks32.

According to the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship33, the amount of water the atmosphere can hold is temperature dependent. As temperatures increase, the capacity for the atmosphere to hold water increases as well34. VPD represents the difference between the actual amount of water vapor in the atmosphere and the amount of water vapor the atmosphere can hold at saturation. It is a measure of atmospheric demand for, or capacity to hold, water35,36,37. To better understand how projected increases in VPD will impact water fluxes during drought and increase the risk of fire at local, regional, and continental scales, there is a need for a high-resolution VPD dataset that considers climate and land cover across ecoregions. Currently, research and operations that require VPD for their analyses often have to compute VPD from ground-based38,39 or satellite remote sensing40,41 measurements of temperature and relative humidity because most datasets do not contain VPD measurements. Ecosystem-to-continental scale modeling and observational studies analysing plant responses to increased VPD would benefit from a fine scale, gridded VPD data product, like the one presented here.

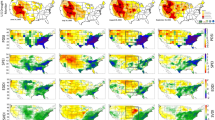

Current available datasets that contain VPD for CONUS are point-scale measurements. The observational network AmeriFlux42 provides sub-daily measurements of temperature and relative humidity from eddy covariance flux towers and, for select sites, provides VPD for users. AmeriFlux has ∼500 sites spread across North and South America, with many sites concentrated near agricultural areas, specific research stations, and universities. As a result, there are large areas missing ground observations, including parts of the Rocky Mountains and the Great Basin Desert43 (Fig. 1). Despite the sparse distribution of AmeriFlux sites across the United States, the diversity of land cover types and climate regions are well-represented44.

Map of Köppen-Geiger climate classification on the 1 km by 1 km CONUS+ grid. The color scheme was adopted from Peel et al.67. The 253 AmeriFlux sites are indicated with markers representing the IGBP Vegetation Land Cover.

At present, there is no single gridded dataset of VPD for all of CONUS that is freely available. Moreover, to our knowledge, no dataset has derived VPD while accounting for specific land cover and climate types. There are, however, existing methods to produce gridded, continental-scale VPD data from reanalysis or satellite-remote sensing. One limitation related to using these approaches is the coarse spatial or temporal resolution of freely-available datasets. The North American Land Data Assimilation system (NLDAS-2) is a reanalysis dataset that provides hourly temperature, pressure, and specific humidity at an 1/8th degree (∼12.5 km) spatial resolution that can be used to derive estimates of VPD8. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) also produces an hourly global reanalysis dataset of meteorological variables, ERA545, with a horizontal spatial resolution of 31 km, which can be used to compute VPD46. Though the hourly resolution of the reanalysis data is useful for when accounting for diurnal fluctuations in VPD, the large spatial resolution extends beyond the fetch of an eddy covariance tower47. Zhang et al.40 demonstrated how to compute daily VPD over China using satellite imagery from the Moderate Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) at a 1 km spatial resolution. The method, which uses MODIS to estimate temperature and humidity, derives an empirical relationship from ground observations. The method is only valid in sites with weather stations and is prone to cloud contamination of surface reflectance40. Moreover, the 8-day observations likely do not capture day-to-day fluctuations in land surface and atmospheric water statuses that impact VPD. To overcome the limitations of the previously mentioned approaches to estimating VPD, we integrated climate and land cover classifications with ground-based observations from AmeriFlux, along with a validated high-resolution temperature and atmospheric vapor pressure product available at a 1 km spatial resolution and daily timestep. This approach informs estimates of VPD, culminating in a gridded VPD product for all of CONUS+. The CONUS+VPD datasets generated in this study have wide ranging applications: VPD can be used to study ecosystem functioning9,14,38,48,49, drought monitoring and prediction8,50,51, or assessing fire risk24,25,26,52,53.

Methods

Overview

In this study, we used meteorological variables of average daily atmospheric vapor pressure (e) and maximum daily temperature (Tmax) from Daymet54, alongside ground based VPD from AmeriFlux eddy covariance towers with a variety of land cover and climate types (Fig. 1), to produce a high-resolution (1 km, daily) gridded VPD data product for CONUS+. Deriving estimates of VPD for CONUS+ consisted of two phases (Fig. 2): (1) Develop land cover and climate dependent correction factors using AmeriFlux observations, (2) Apply correction factors to all pixels in the CONUS+ grid. In Phase 1, we first computed 24-hour average VPD from 253 AmeriFlux sites with varying climate and land cover classifications. We then calculated VPD using Daymet e and Tmax. We chose to use Tmax instead of another daily temperature averaging scheme (e.g.37,55,56,57) because using Tmax better recreates day-to-day variability in VPD. However, it also overestimates daily VPD (Fig. 3). In order to correct the overestimation, we computed the median ratio of AmeriFlux to Daymet-derived VPD for each land cover type and climate classification. In Phase 2, we estimated VPD for the entire CONUS+ grid. We adjusted the Daymet-derived VPD for each grid cell based on its climate or land cover type by applying the corresponding correction factor (i.e., median ratio) developed in Phase 1. This generated two 24-hour average VPD datasets: one informed by land cover and one informed by climate. The resulting Daymet-derived VPD datasets for CONUS+ are evaluated against daily average VPD computed from hourly AmeriFlux VPD data not previously used in the analysis, NLDAS-2 derived VPD, and VPD computed using a weighted temperature averaging scheme.

Two-phase summary of workflow. In Phase 1, we use AmeriFlux VPD to correct estimates of VPD derived from Daymet variables maximum daily temperature, Tmax and average daily vapor pressure e. In Phase 2, we apply correction factors to every grid cell in CONUS+ by matching each grid cell with the corresponding International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) and the Köppen-Geiger (KG) climate classification.

Datasets

Daymet

Daymet is a freely available collection of daily, 1 km, gridded meteorological data products derived from weather stations throughout North America58. Weather station data is used to inform daily estimates of Daymet’s primary output variables: minimum and maximum temperature (Tmin and Tmax, respectively) and total precipitation. Daymet also produces secondary variables of average daytime shortwave radiation, average atmospheric water vapor pressure (e), and accumulated snow water equivalent, which are derived from the primary variables59,60. Day length is also provided as an estimate based on geographic location58. For this study, we used Daymet Tmin, Tmax, and e from 1995 to 2023, corresponding with available data records from ground based AmeriFlux eddy covariance towers. Tmin and Tmax were used to estimate saturated vapor pressure, esat, from which we subtract e to estimate VPD.

For this study, daily minimum and maximum temperature and average vapor pressure were acquired from the Daymet Version V4R154 (Fig. 4). Daymet data were directly downloaded from https://daac.ornl.gov/. Daymet V4R1 updated V4 by correcting a daily data feed error and imputing missing readings for 2020 and 202158. Daymet V4 uses weather inputs from the National Centers for Environment Information Global Historical Climate Network Daily database. Daymet V4 updated previous Daymet algorithms to account for observation reporting time and high elevation biases which can affect daily maximum temperature and precipitation accumulations. For each 1 km by 1 km Daymet grid cell, a normalized weighted interpolation is used to estimate both Tmin and Tmax from three-dimensional temperature gradients using data from weather stations within a predefined search radius58. Daily average vapor pressure, e is computed using Tmin as a proxy for dew point temperature and implementing aridity adjustments61 which require potential evapotranspiration derived from shortwave radiation60.

AmeriFlux

AmeriFlux is a network of eddy covariance flux towers, distributed across North, Central, and South America, collecting semi-continuous measurements of carbon, water, and energy fluxes42,44,62. The AmeriFlux data was used for rescaling Daymet-derived VPD at the tower sites and validating the CONUS+ gridded VPD product. We downloaded all AmeriFlux data used in this study from https://ameriflux.lbl.gov/, using the “Site Search” tool to select 253 sites from the nearly 500 AmeriFlux sites by considering sites in CONUS+ which had half-hourly VPD, record lengths of at least one year, and which share their data under the AmeriFlux CC-BY-4.0 License. Time series of VPD observations are provided at half-hourly increments, with records spanning 1995 to 2023; however, most sites do not have records spanning the entire time interval. The 253 sites used in this study met the criteria of having at least one complete year of VPD observations, totaling over 1400 site years of data across all sites (Tables 1 and 2). We computed daily estimates of AmeriFlux VPD (VPDAMF) by averaging over all 48 half-hour measurements within a single day. AmeriFlux reports VPD in hectopascals (hPa), except for some older sites which reported VPD in kilopascals (kPa). All VPD data from AmeriFlux were converted to units of kPa. AmeriFlux provides ancillary information about the geographic location (latitude and longitude coordinates), land cover (International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, IBGP), and climate (Köppen-Geiger, KG) for each site. We used the IGBP and KG classifications as provided from AmeriFlux to develop relationships between AmeriFlux and Daymet daily average VPD. From the 253 sites, there were 14 unique IGBP land cover and 16 unique KG climate classifications (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). To provide independent validation, we computed daily average VPD from five AmeriFlux sites that provided hourly VPD and were not included in estimating the correction factors from Phase 1 for the final gridded CONUS+ VPD product.

A summary of the 253 AmeriFlux IGBP and KG classifications, the proportions of sites they represent, and the respective total number of site years can be found in Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 5. KG classification Cfa (temperate, no dry season, hot summer) was the most represented classification in this analysis with 68 sites (26.9%) throughout the Southeastern US (Fig. 5). The next most common KG climate classifications was Dfb (cold, no dry season, warm summer) with 52 sites (20.6%), followed by Dfa (cold, no dry season, hot summer) with 32 sites (12.6%). Of the 253 sites in this study, croplands (CRO), evergreen needle leaf forests (ENF), and grasslands (GRA) were the most-represented IGBP land cover classifications, representing 23.3%, 22.1%, and 15.8% of the total sites, respectively. The proportion of sites a classification represents does not necessarily translate to the amount of data used in this study because some sites may have longer temporal records of VPD. For example, there are 16 more sites with KG classifications Cfa than with Dfb, but Dfb had 331 site years of data compared to Cfa which had 328 sites years of data. With 413.8 site years, ENF was the land cover classification with the most data, nearly twice as many site years as CRO despite having only three fewer tower sites. Overall, climate and land cover from AmeriFlux towers represented well the actual coverage of CONUS+ with a few exceptions. With 9.1% of sites and 158.9 site years of data, the KG classification Csa (temperate with dry, hot summer), a Mediterranean climate found in California, were over represented by the site data since only approximately 1% of the CONUS+ grid is classified as Csa. Alternatively, woody savannas (WSA) were underrepresented as they make up 2% of AmeriFlux sites but 12.6% of the CONUS+ gird.

IBGP land cover

IGBP land cover was used to classify AmeriFlux sites and for estimating VPD at the continental scale. Land cover classifications for pixels in the CONUS+ grid were generated from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Land Cover Type Product (MCD12Q1) Land Cover Type 1, which provides annual land cover from 2001–2023 at a 500 m spatial resolution using IGBP classes63. MODIS MCD12Q1 Land Cover Type 1, the Annual IGBP classification, was selected to align with the AmeriFlux provided IGBP land cover. The freely available MODIS land cover data were downloaded from AρρEEARS64 (https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov) using the “Extract Area Sample” download tool with geographic coordinate projection. The 500 m MODIS was upscaled to the Daymet 1 km grid using a nearest neighbor interpolating algorithm. The AmeriFlux sites represented 14 of the 17 MODIS IGBP classes (Table 1). The three unrepresented IBGP land cover classes include deciduous needleleaf forests (DNF), which comprises approximately 0.005% of CONUS+ pixels, evergreen broadleaf forests (EBF) and permanent snow/ice (SNO), which together make up approximately 0.8% of pixels.

Köppen geiger climate

The gridded updated Köppen Geiger (KG) climate classifications were obtained from Beck et al.65,66. The KG classifications were also used to classify AmeriFlux sites and estimate VPD for CONUS+. The KG classifications are available at 1 km by 1 km spatial resolution, which we realigned to match the 1 km CONUS+ grid using a nearest neighbor approach. There are five main categories of classification, each broken down into subcategories, yielding a total of 30 unique classifications globally67. For CONUS+ grid, there were only 25 unique KG values. The AmeriFlux sites represent 16 KG classifications. In order to determine correction factors for the remaining nine KG classifications, we reclassified them following Table 3.

North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS)

Reanalysis data from North American Land Data Assimilation System phase 2 (NLDAS-2) Forcing File A68 was used to estimate an independent VPD product for evaluation of the CONUS+ VPD dataset. NLDAS integrates a multitude of guage-, radar-, and model-based observations using the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Eta Data Assimilation System (EDAS) to generate forcing data for all of CONUS at an hourly timestep and at a 0.125° by 0.125° spatial scale69. The freely available NLDAS-2 variables of 2-m above ground temperature temperature (TMP), 2-m specific humidity (SPFH), and surface pressure (PRES) were downloaded using the NASA GES DISC (https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/) dataset subset tool70. VPD was calculated following the method described in Lowman et al.8. Daily average temperature from NLDAS-2 was used to estimate esat from Teten’s equation and vapor pressure, e, was estimated using average daily specific humidity and air pressure.

Estimating VPD for CONUS+

In order to generate a daily gridded VPD dataset for CONUS+, we used the meteorological variables from Daymet, VPD from AmeriFlux, land cover classifications from MODIS, and climate classifications from KG. The temporal coverage of MODIS land cover was the limiting factor for the start and end dates of the data records produced in this study. At the time of development, the MODIS land cover record was 2001 to 2023, so this twenty-three-year period defined the date range for land cover correction. We assumed a single KG classification for each pixel of CONUS+ for the entire study period (i.e., no pixels changed climate classification).

Calculating VPD from Daymet - Phase 1

Calculating VPD for each AmeriFlux site required first identifying the Daymet 1 km by 1 km grid cell whose center was nearest the site’s geographic coordinate and extracting the Daymet variables (Fig. 2). Daily average VPD, in kPa, was calculated as the difference between saturated, esat, and unsaturated, e, vapor pressure

where e is provided by the Daymet daily average vapor pressure data and esat is calculated using Teten’s equation33,71:

The variable T* (°C) is a representative temperature computed using the Daymet maximum and minimum daily temperatures (Tmax and Tmin, respectively). The parameters A and B are empirically determined with \(A=17.27\) and \(B=237.15\) when \(T\ge {0}^{^\circ }C\), and \(A=21.87\) and \(B=265.5\) when \(T < {0}^{^\circ }C\)33,72. It is a known issue that calculating saturation vapor pressure using the above freezing coefficients in Eq. 2 to below freezing temperatures results in large errors72. In our calculations we used \({T}^{\ast }={T}_{max}\). Prior studies used a weighted average of Tmax and Tmin, \({T}^{\ast }={T}_{W}=0.606{T}_{max}+0.394{T}_{min}\), which puts more emphasis on Tmax57,73. The TW method is presented in the earliest Daymet derivations of meteorological variables as a way to estimate average daily temperature57. In this method, Tmin and Tmax are used to fit a sine curved to simulate diurnal changes in temperature, with the average value of the sine curve representing the average value of daytime temperature73. Unsaturated vapor pressure provided by Daymet uses Tmin as a representative of dew point temperature57. We compared how estimating esat using Tmax or TW as T* influences estimates of VPD computations.

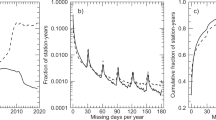

Computing Correction Factors - Phase 1

We found that using TW did not capture day-to-day variability in observed VPD from the AmeriFlux towers while preliminary analysis showed calculations of \(VPD({T}^{\ast }={T}_{max})\) matched day-to-day fluctuations while overestimating daily AmeriFlux VPD (VPDAMF) (Fig. 3). To reduce the difference between \(VPD({T}_{max})\) and VPDAMF, we developed a method to scale \(VPD({T}_{max})\) using ratios based on AmeriFlux climate and land cover classification. In Phase 1, we computed daily \(VPD({T}_{max})\) for each AmeriFlux site from 1995 to 2023 and grouped all computations by KG and IGBP classifications. We computed ratios, R, of AmeriFlux to Daymet VPD at every time-step for all sites and all years with data within a given classification according to

where ti is the daily timestep. We binned the ratios by IGBP (KG) and found the mean and median across all sites with the same land cover (climate) classification. Thus, a site with more years of data was weighted more when computing the correction factors across all sites. Because the mean values could be skewed by large outlier ratios, we used the median ratio as the correction factor for the jth land cover type (climate classification) across all sites and time with land cover (climate) j,

There were five sites with climate listed as unknown (Unk), which were excluded from the correction factor development. We then computed new scaled VPD values at each time step, ti by multiplying \(VP{D}_{{T}_{max}}({t}_{i})\) by the appropriate land cover (climate) correction factor, Rj,

Median ratios, along with their means and standard deviations, are provided for all land cover and climate classifications in Tables 4 and 5.

Generating CONUS+ VPD - Phase 2

To generate daily maps of VPD for all of the CONUS+ grid, we computed daily \(VPD({T}_{max})\) for every pixel and multiplied the daily value by the appropriate correction factor using Eq. 5. However, the AmeriFlux towers used to generate the correction factors only provide a sample of IGBP and KG classifications, and in some instances, the interpolated land cover and climate classification for pixels containing AmeriFlux towers may differ from the classifications provided by AmeriFlux. For the missing 3 IGBP classes mentioned above (DNF, EBF, and SNO), no correction factor was applied to the CONUS+ \(VPD({T}_{max})\). There were 25 out of 30 KG classes represented in the CONUS+ grid, with 16 unique KG values represented by the AmeriFlux sites, requiring the need to determine the correction factors for 9 different KG values. We used ratios from the most similar climate classifications as the correction factors for unrepresented KG values, as summarized in Table 3. The differences in KG classifications and their replacements are in the third letter of the short-name classifications, which indicates summer temperatures67. The nine unrepresented KG classes are (Af, Am, Aw, Csc, Cwb, Cfc, Dsc, Dwa, EF). KG classifications with leading “A” are all tropical, and we had no tropical climates represented in the AmeriFlux site data, however, extreme biases exist if no correction factors were applied to these pixels (i.e., \({R}_{j}=1\)), which comprise <0.3% of pixels in the humid south of Florida. So, we replaced Af, Am, and Aw, with climate Cfa which covers most of the Southeastern US, including Northern Florida.

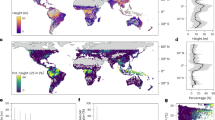

Data Records

The dataset, along with supporting data generation and evaluation codes, are available as a resource in the HydroShare repository74. Two different CONUS+ VPD datasets were created: one for \(VPD({T}_{max})\) scaled by the Köppen-Geiger (KG) climate classification, and one scaled by MODIS Land Cover Type 1 (IGBP) classification. We provide 23 years of daily, gridded VPD data spanning the period 2001–2023. The gridded data products are available as netCDF files covering CONUS+, with bounding box 25 to 50°N latitude and 67 to 125°W longitude (Fig. 6). Each netCDF files contains one year of data, with data arrays having dimensions 5731 by 3122 by 365. The first two dimensions correspond with the dimensions of the CONUS+ grid, and the third dimension represents each day of the year. Daymet provides 365 days of temperature and vapor pressure for each day of the year. In leap years, day 365 corresponds with December 30 and no data is provided for December 31. We follow the same convention. The VPD data are stored as 16-bit unsigned integers in Pascals. Therefore, a correction factor of 10−3 must be applied to convert the values into units of kPa. In the repository, we also provide netCDF files of the CONUS+ grids of KG and yearly IBGP values, along with.csv files containing tables of the corresponding correction factors. NaNs (indicating not-a-number) are used to fill values where the VPD data is unavailable, which usually occurs over oceans and larger bodies of water. There are two additional scripts provided in the HydroShare repository to assist users in: (1) Plotting CONUS+ maps of VPD for any day of year and (2) Extracting VPD time series data for any location (i.e., pixel) or set of locations in the CONUS+ grid.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the performance of CONUS+ scaled VPD products (VPDS), \(VPD({T}_{W})\), and VPDNLDAS by comparing each to AmeriFlux VPD (VPDAMF) using a variety of error metrics. We found that both land cover and climate informed VPD datasets compare more favorably against AmeriFlux than daily VPD estimated by average daily temperature or NLDAS-derived VPD (Table 6). We further evaluated how the method performs across specific IGBP land cover and KG climate classifications, summarized in Tables 4 and 5. Lastly, we performed independent evaluations of VPDS at five sites that provided only hourly VPD and were not included in the correction factor development: US-Cop, US-Cwt, US-MMS, US-PFa, and US-UMB (Table 7, Fig. 7).

Time series of scaled Daymet VPD compared with AmeriFlux, and NLDAS for US-MMS and US-PFa, and a map of the independent sites not included in the correction factor development whose error metrics are in Table 7. Pop outs show days 100–150 and 175–225 for US-MMS and days 125–175 and 200–250 for US-PFa.

Error metrics

The error metrics presented are mean bias error (MBE), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE), unbiased RMSE (uRMSE), and the Pearson correlation coefficient (rp) for each classification j at time ti, \(i\in 1,...,N=365\), and were computed as

and

The error metric MBE can be any positive or negative value while MAE and RMSE are non-negative. Positive (negative) values of MBE indicate VPDS is greater (less) than VPDAMF, on average. Here, positive MBE indicates VPDS overestimates VPDAMF. Large errors with opposite signs can negate one another in calculations of MBE, resulting in small bias errors. By taking the absolute value of each daily error, MAE provides a measure of the overall magnitude of the differences between VPDAMF and VPDS. Like MAE, squaring the difference between VPDAMF and VPDS in RMSE makes the error positive, but it also provides more weight to large error and less weight to small errors. To remove the effects of systematic bias in the bulk error estimates of RMSE for independent study sites, we computed uRMSE75. The Pearson correlation coefficient (rp), which ranges between -1 and 1, is a metric of the linear relation between VPDAMF and VPDS. The closer the magnitude of rp is to one, the more linear the relationship between the two, with the sign of rp indicating whether or not the relationship is positive or negative. Overall, MBE, MAE, RMSE, and uRMSE closer to zero, and rp closer to one, indicate the Daymet-derived VPD aligns well with observations from AmeriFlux.

Overall performance of correction factors

While the Pearson correlation coefficients were similar in the VPDs, \(VPD({T}_{W})\) and VPDNLDAS methods, there were differences in the other error metrics (Table 6). The negative MBE indicates that the correction factors tended to underestimate daily averages of AmeriFlux VPD. However, for Daymet VPD scaled by IGBP or KG, those overestimates were ∼0.02 kPa versus the overestimate of 0.18 kPa using a weighted temperature approximation. The MAE from scaling VPDs was 29% smaller than \(VPD({T}_{W})\) across all sites. The RMSE for \(VPD({T}_{W})\) compared to VPDAMF was 0.14 kPa higher than the RMSE using the VPDs methods. Even after removing bias, the uRMSE is stil 0.1 kPa higher than VPDs. While VPDNLDAS has better error metrics than \(VPD({T}_{W})\), the uRMSE value of 0.340 kPa is 0.06 kPa larger than either the land cover or climate corrected VPD. The results indicate that on average, and in extreme cases, across all sites, using land cover and climate to inform the scaling of \(VP{D}^{j}({T}_{max})\) outperformed estimates of \(VPD({T}_{W})\) and VPDNLDAS.

Within the scaling methods, scaling VPD by land cover or by climate tended to have similar values across error metrics (Table 6), but performance varied within classifications (Tables 4 and 5). While most of the correction factors had standard deviations less than 0.4, some standard deviations were orders of magnitude larger. For example, the standard deviation for the IGBP land cover grassland (GRA) was over 5. This was due to a few large ratios (over 10) with the largest being 1067. Large ratios can happen when the denominator, in this case \(VP{D}^{j}({T}_{max})\), is near zero. Nearly all of the large ratios occurred in winter months with temperature below freezing. The coefficients for below freezing temperatures used in Eq. 2 to compute saturated vapor pressure allowed for saturated vapor pressure to be nearly the same as actual vapor pressure, resulting in VPD near zero (i.e. on the order of 10−4 kPa). In total, this happened for the IGBP land cover class GRA on 52 days, and since there were over 1400 site years of data, we did not remove these values. Data from sites US-NR3 and US-NR4 were the leading contributors to the large standard deviations for GRA, being responsible for 38 of the 52 ratios greater than 10 and all six ratios great than 100. In those instances where the ratios were greater than 100, \(VP{D}^{j}({T}_{max})\) (the denominator) was between 0.0002 and .0005 kPa while \(VP{D}_{AMF}^{j}\) (the numerator) fell between 0.1 and 0.2 kPa. Similarly, there was a very high standard deviation of 19.2 for the KG climate classification ET. There were only two sites that have KG classification ET, US-NR3 and US-NR4, explaining why these two classifications had higher standard deviations for the mean of the correction factors. Despite high standard deviations, the average errors associated with the application of correction factors to scale \(VPD({T}_{max})\) were unaffected by the few extreme values due to the total number of records used in the analysis and the fact that we adopted the median values as the correction factors when applying them to CONUS+. The magnitude of the error metrics MBE, MAE, and RMSE were smaller for the two ET sites than for the KG corrected methods across all sites (Tables 4 and 5). This suggests that the high standard deviation of the correction factors did not negatively affect the ability of the correction factors to accurately scale \(VP{D}^{j}({T}_{max})\).

The rp values correlating the VPDs and VPDAMF were strong (i.e., \({r}_{P} > 0.5\)) for most classifications, with most \({r}_{P} > 0.8\), the highest of which came from the open shrubland (OSH) IGBP classification, with \({r}_{P}=0.945\) and KG climate Dsb (cold, dry, warm summer), with \({r}_{P}=0.951\). The KG classifications Cwa (temperate, dry winter, warm summer) had the least linear relationship, \({r}_{P}=0.327\). This classification was only represented by 4 sites (Fig. 5) and 15.6 site years (Tables 1 and 2). And while there was not as strong of a linear relationship for Cwa when compared to VPDAMF, the overall accuracy indicated by other metrics validates the performance of the correction factor.

Considering, the method of scaling by IGBP land cover, the algorithm had the smallest error metrics for cropland/vegetation mosaics (CVM, Table 4) with MBE of -0.004 kPa, MAE of 0.158 kPa and RMSE of 0.201 kPa. However, there was only one site with 5.6 years of data, so CVM was not the most well represented land cover. With 56 sites and over 400 site years of data, evergreen needleleaf forests (ENF) were the most represented land cover. The correction factor median for ENF was 0.416, with a mean and standard deviation of 0.455 and 0.699, respectively. Despite the standard deviation being larger than the correction factor, there was a strong linear relationship (\({r}_{P}=0.840\)) between VPDs and \(VPD({T}_{max})\). The error metrics MAE, MBE, and RMSE for ENF were comparable to the same metrics across all IGBP classifications. Climate classifications Cfb (Temperature, no dry season, warm summer) and ET (Polar tundra) had some of the lowest error metrics but were only represented by one and two sites, respectively. Classification Cfa (Temperate, no dry season, hot summer), which covers most of the Southeast US and was represented by almost 27% of the study sites with 328 site years of data, had errors only slightly worse than the average across all climates.

VPD Uncertainty Analysis

Evaluating VPD for Independent AmeriFlux Sites

For the correction factor development presented above, we used AmeriFlux VPD for sites that reported half-hourly data. For time series analysis, we identified five sites inside of CONUS+ that provided hourly data and were not included in the correction factor development: US-Cop (GRA, no climate reported but interpolated as Bsk), US-Cwt (DBF, Dfb), US-MMS (DBF, Cfa), US-PFa (MF, Dfb), and US-UMB (DBF, Dfb). We scaled \(VP{D}^{j}({T}_{max})\) for these for sites using correction factors corresponding with the AmeriFlux provided vegetation land cover and climate. Error metrics for those sites are found in Table 7 and example time series for two sites for select years are shown in Fig. 7.

Error metrics indicate strong performance of VPDs relative to AmeriFlux VPD at US-Cwt, US-MMS, US-PFa, and US-UMB. For each of the four sites, uRMSE is smaller than the respective error for the same land cover and climate classifications (Tables 4 and 5). Performance of VPDs is weakest at US-Cop, a grassland in a cold, arid environment. AmeriFlux tends to have higher VPD than VPDs and VPDNLDAS at this site as seen in the negative MBE values (Table 7). Error metrics for the land cover and climate corrected VPD were lower than VPDNLDAS at US-MMS, US-PFa, and US-UMB, the three sites with the longest temporal records. VPDs and VPDNLDAS differed in uRMSE at US-Cwt by 0.005 kPa, indicating that our scaled VPD generally outperforms NLDAS across the five test sites. Even for NLDAS, error metrics are highest at US-Cop. The high RMSE values of 0.752 and 0.566 for land cover and climate corrected VPD, respectively, indicate the largest errors occurred during periods of elevated VPD. The lower uRMSE values for VPDs indicate that our methods capture the variability in daily VPD better than alternative methods. For example, during green up at US-MMS (days 100 to 150) and the middle part of the growing season (days 175 to 225) of 2012, the land cover and climate corrected VPD compared more favorably against AmeriFlux VPD than NLDAS, which underestimated AmeriFlux during green up and overestimated AmeriFlux in days 180 to 210 of 2012 (Fig. 7), a time period of an extreme drought in the Midwest76.

Uncertainty in Land Cover and Climate Classifications

We generated land cover and climate dependent correction factors using VPD from 253 AmeriFlux eddy covariance flux towers, however several land cover and climate classifications had less than five representative sites. For IGBP land cover, there was only one site classified as cropland/natural vegetation mosaics (CVM), two sites classified as barren sparse vegetation (BSV), and three sites classified as closed shrubland (CSH). For KG climate, one site represented classification Cfb (temperature, no dry season, warm summer), while classifications Bwh (arid, desert, hot), Dsa (cold, dry and hot summer), ET (polar tundra) each had 2 sites. Classifications Bsh (arid, steppe, hot) and Dwb (cold, dry winter, warm summer) had three sites each, and there were four sites with classification Cwa (temperature, dry winter, hot summer). No tropical sites were represented by the AmeriFlux sites. In contrast, several land cover and climate sites represented significant portions of the 253 sites. There were 59 sites classified as croplands (CRO), 56 as evergreen needleleaf forests (ENF), and 40 as grasslands (GRA). There were and 68 sites with KG climate classification Cfa (temperate, no dry season, hot summer), and 52 classified as Dfb (cold, no dry season, warm summer). It is possible that having a larger sample of underrepresented classifications, in more regions across CONUS+, could have improved performance. Additionally, most AmeriFlux sites are located in heterogeneous landscapes, and the heterogeneity has been shown to influence the variability of VPD in the local microclimate9. This consideration is important for researchers investigating the variability in ecosystem responses to variations in VPD.

Usage Notes

Research to Operational Applications

This dataset offers users a chance to perform fine spatial and temporal scale investigations in a variety of climate and land covers across CONUS+ which is particularly beneficial for studying areas with limited or no available ground data records of VPD. To conduct a point or other small-scale study, a user would need to identify a latitude/longitude coordinate pair (or set of coordinate pairs for multiple sites or for a small region) and the corresponding grid location(s) from the dataset. A time series of VPD could be useful for many reasons. For example, one could follow the methods described by Yuan et al.4 or Li et al.77 to analyze the VPD dependence of carbon assimilation on plant growth. Since the influence of VPD on vegetation growth can vary by region19, users could separate the data by land cover or climate to explore how VPD affects carbon assimilation and plant growth vary by climate and land cover.

Because VPD is linked to drought50, with high VPD corresponding to dry conditions, this dataset could be useful in tracking VPD anomalies that may be associated with drought identification and intensification for all of CONUS+, supporting a suite of indices and anomalies already implemented as drought markers78. One such index, the evaporative stress index (ESI) or ratio (ESR) considers more than precipitation anomalies by computing the ratio of actual evaporation to potential evaporation78, which depends on VPD79, and has been shown to effectively track rapid changes in drought conditions80. Generating standardized VPD anomalies in similar ways could be additionally effective ways to study the direct influence of VPD on drought development. Additionally, when analyzed with covariates such as precipitation and soil moisture8, this dataset could be useful in identifying VPD-induced drought thresholds across land cover and climate classifications, similar to Lowman et al.8.

VPD is a variable of interest to a broad range of the environmental and geophysical science communities, spanning climatology, ecology, ecophysiology, and beyond. Daymet has a meteorological record that dates back to 1980 for most of North America58. With over forty years of temperature and vapor pressure data, those interested in longer-term climatological studies could use this data and adapt our methods to extrapolate VPD back to 1980 and into the future to investigative how VPD is changing at climatological time scales, especially with changing land cover and climate classifications. For those interested in purely atmospheric studies, this dataset could also be useful for research investigating how vapor pressure changes within the vertical atmospheric column by providing surface or near surface VPD. Because of the wide range of altitudes spanning CONUS+, these datasets could be used with elevations maps to investigate how plant function, such as photosynthesis, varies with VPD across altitudinal gradients81. Fire and other disturbances, such as tropical cyclones, can impact the local VPD by altering the local climate and landscape82. Studies of how surface VPD anomalies impact wildfire risk24 across land cover and climate regions in CONUS+ will benefit from using this dataset in conjunction with other fire related data products.

We anticipate land managers, using research to inform operations, to access this dataset to assess when and how crop yields begin to be impacted during VPD-induced drought, and to evaluate the resiliency of various croplands to high VPD in different climates. This type of scientific inquiry can guide agricultural strategies to mitigate the effects of changing atmospheric demand for water. Similarly, studies using these datasets to investigate the impacts of high VPD on wildfire risk could be translated into protocols for forest management decisions to determine wildfire risk status.

Alternative Ways to Use the VPD Products

We encourage users to consider the land cover and climate classifications of their study sites when using this data product. Outputs between the two VPD products are similar, but subtle differences exists (Fig. 6). In areas like the Southeastern US, where land cover can be heterogeneous but climate is homogeneous over are large region, \(VP{D}_{S}^{KG}\) tends to be smoother than \(VP{D}_{S}^{IGBP}\). In some applications users may prefer to use daily maximum VPD (i.e., VPD (Tmax)) as a proxy for maximum daily water stress50. VPD (Tmax) can be obtained for any pixel by dividing by the correction factor. Additionally, users may want to account for both climate and land cover. To do so, they would divide by the correction factor before applying a correction factor from a different classification, or some combination of correction factors. For example, if a user is working with a site and they want to combine the effects of land cover and climate classification, they could scale VPD (Tmax) using the average of the IGBP and KG correction factors for that site. Or users could attempt to incorporate vegetation heterogeneity by combining correction factors for one or more vegetation types.

We assumed land cover changes occurred annually according to MODIS IGBP. One could update this VPD product using the newest available MODIS IGBP records in the future. Additionally, users may want to extend records further back (prior to 2001) in which case they could assume prior land cover, with caution, and use the land cover map of correction factors to apply to earlier Daymet records. With MODIS going offline in the near future, it may also be possible to follow this procedure with different land cover classification schemes. Similarly, any updated climate classification schemes could be applied to any future Daymet data records or those prior to 2001 in order to expand the available date record of VPD (Tmax). The methods presented here could also be adapted for regions across the world, especially in areas with similar climates and or land cover to CONUS+. Studies investigating VPD in arctic and tropical regions could follow the methods presented here but would benefit from a dataset developed using additional ground observations from those regions.

Transferability Outside of CONUS+

The methods presented in this manuscript can be adapted to other study regions as long as investigators account for the resolution of the temperature, vapor pressure, land cover, and climate inputs. Here, the MODIS land cover data is 500 m and the Koppen-Geiger climate 1 km, which were each resampled to align with the Daymet CONUS+ grid at 1 km. This method could be directly applied to the entire Daymet spatial coverage (Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Mexico and Canada) because there are AmeriFlux and/or FluxNet towers to provide ground observations of VPD. Outside of those regions, Daymet is not available. Thus, some alternative meteorological data set would need to be used (e.g., Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series83). The land cover and climate data are each available globally so applying the methods presented requires subsetting land cover and climate and aligning it to match the resolution of the temperature and atmospheric vapor pressure data of the new study region. FLUXNET data could be applied to a wider range of regions (e.g., South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe42). Otherwise, the key limitation to applying this approach is the availability of ground observations needed to build correction factors for the daily estimates of VPD.

Working with NetCDF Files

The datasets are available in netCDF file format. NetCDF files are commonly used formats for storing array data. They are easily readable by most software applications (e.g., Python, R, Matlab, Fortran, etc.). For more information and resources about netCDF files, visit https://www.unidata.ucar.edu/software/netcdf/. Additionally, users can subset, visualize, or analyze the netCDF files in the HydroShare resource using the THREDDS (Thematic Real-time Environmental Distributed Data Services) data server. For help with using THREDDS, visit https://help.hydroshare.org/apps/thredds-opendap/.

Code availability

All codes used to generate, visualize, and subset the data are freely available as part of the same resource as the VPD datasets in CUAHSI HydroShare74.

References

Dai, A., Zhao, T. & Chen, J. Climate change and drought: a precipitation and evaporation perspective. Current Climate Change Reports 4, 301–312, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0101-6 (2018).

Miralles, D. G., Gentine, P., Seneviratne, S. I. & Teuling, A. J. Land–atmospheric feedbacks during droughts and heatwaves: state of the science and current challenges. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1436, 19–35, https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13912 (2019).

Novick, K. A. et al. The increasing importance of atmospheric demand for ecosystem water and carbon fluxes. Nature climate change 6, 1023–1027, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3114 (2016).

Yuan, W. et al. Increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Science advances 5, eaax1396, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax1396 (2019).

Lobell, D. B. et al. Greater sensitivity to drought accompanies maize yield increase in the us midwest. Science 344, 516–519, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251423 (2014).

Zhao, M. & Running, S. W. Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009. science 329, 940–943, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192666 (2010).

Otkin, J. A. et al. Assessing the evolution of soil moisture and vegetation conditions during the 2012 united states flash drought. Agricultural and forest meteorology 218, 230–242, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.12.065 (2016).

Lowman, L. E., Christian, J. I. & Hunt, E. D. How land surface characteristics influence the development of flash drought through the drivers of soil moisture and vapor pressure deficit. Journal of Hydrometeorology 24, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-22-0158.1 (2023).

Novick, K. A. et al. The impacts of rising vapour pressure deficit in natural and managed ecosystems. Plant, Cell & Environment https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.14846 (2024).

López, J., Way, D. A. & Sadok, W. Systemic effects of rising atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on plant physiology and productivity. Global Change Biology 27, 1704–1720, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15548 (2021).

Qin, Z. et al. Identification of important factors for water vapor flux and co2 exchange in a cropland. Ecological modelling 221, 575–581, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.11.007 (2010).

Monteith, J. L. Evaporation and environment. In Symposia of the society for experimental biology, vol. 19, 205–234 (Cambridge University Press (CUP) Cambridge, 1965).

Liu, M. et al. Overridingly increasing vegetation sensitivity to vapor pressure deficit over the recent two decades in china. Ecological Indicators 111977, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111977 (2024).

Grossiord, C. et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytologist 226, 1550–1566, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16485 (2020).

Merilo, E. et al. Stomatal vpd response: there is more to the story than aba. Plant physiology 176, 851–864, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00912 (2018).

Schönbeck, L. C. et al. Increasing temperature and vapour pressure deficit lead to hydraulic damages in the absence of soil drought. Plant, Cell & Environment 45, 3275–3289, https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.14425 (2022).

Anderegg, W. R., Kane, J. M. & Anderegg, L. D. Consequences of widespread tree mortality triggered by drought and temperature stress. Nature climate change 3, 30–36, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1635 (2013).

Corak, N. K., Otkin, J. A., Ford, T. W. & Lowman, L. E. Unraveling phenological and stomatal responses to flash drought and implications for water and carbon budgets. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 28, 1827–1851, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-1827-2024 (2024).

Zhang, S., Tao, F. & Zhang, Z. Spatial and temporal changes in vapor pressure deficit and their impacts on crop yields in china during 1980–2008. Journal of Meteorological Research 31, 800–808, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13351-017-6137-z (2017).

Kern, A. et al. Statistical modelling of crop yield in central europe using climate data and remote sensing vegetation indices. Agricultural and forest meteorology 260, 300–320, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.06.009 (2018).

Lobell, D. B. et al. The shifting influence of drought and heat stress for crops in northeast australia. Global change biology 21, 4115–4127, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13022 (2015).

Hsiao, J., Swann, A. L. & Kim, S.-H. Maize yield under a changing climate: The hidden role of vapor pressure deficit. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 279, 107692, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.107692 (2019).

Rashid, M. A., Andersen, M. N., Wollenweber, B., Zhang, X. & Olesen, J. E. Acclimation to higher vpd and temperature minimized negative effects on assimilation and grain yield of wheat. Agricultural and forest meteorology 248, 119–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.09.018 (2018).

Seager, R. et al. Climatology, variability, and trends in the us vapor pressure deficit, an important fire-related meteorological quantity. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 54, 1121–1141, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-14-0321.1 (2015).

Chiodi, A. M., Potter, B. E. & Larkin, N. K. Multi-decadal change in western us nighttime vapor pressure deficit. Geophysical Research Letters 48, e2021GL092830, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL092830 (2021).

Williams, A. P. et al. Observed impacts of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire in california. Earth’s Future 7, 892–910, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001210 (2019).

Gonzalez, P., Neilson, R. P., Lenihan, J. M. & Drapek, R. J. Global patterns in the vulnerability of ecosystems to vegetation shifts due to climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography 19, 755–768, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00558.x (2010).

Williams, A. P. et al. Causes and implications of extreme atmospheric moisture demand during the record-breaking 2011 wildfire season in the southwestern united states. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 53, 2671–2684, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-14-0053.1 (2014).

Holden, Z. A. et al. Decreasing fire season precipitation increased recent western us forest wildfire activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, E8349–E8357, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1802316115 (2018).

Littell, J. S., Peterson, D. L., Riley, K. L., Liu, Y. & Luce, C. H. A review of the relationships between drought and forest fire in the united states. Global change biology 22, 2353–2369, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13275 (2016).

Mitchell, R. J. et al. Future climate and fire interactions in the southeastern region of the united states. Forest Ecology and Management 327, 316–326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.12.003 (2014).

Clarke, H. et al. Forest fire threatens global carbon sinks and population centres under rising atmospheric water demand. Nature communications 13, 7161, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34966-3 (2022).

Dingman, S. L. Physical hydrology (Waveland press, 2015).

Abtew, W. & Melesse, A. Vapor Pressure Calculation Methods, 53–62 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2013).

Anderson, D. B. Relative humidity or vapor pressure deficit. Ecology 17, 277–282, https://doi.org/10.2307/1931468 (1936).

Jensen, M. E. Consumptive use of water and irrigation water requirements. American Society of Civil Engineers (1974).

Castellvi, F., Perez, P., Villar, J. & Rosell, J. Analysis of methods for estimating vapor pressure deficits and relative humidity. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 82, 29–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1923(96)02343-X (1996).

Zhang, Q. et al. Response of ecosystem intrinsic water use efficiency and gross primary productivity to rising vapor pressure deficit. Environmental Research Letters 14, 074023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab2603 (2019).

Howell, T. A. & Dusek, D. A. Comparison of vapor-pressure-deficit calculation methods—southern high plains. Journal of irrigation and drainage engineering 121, 191–198, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(1995)121:2(191) (1995).

Zhang, H., Wu, B., Yan, N., Zhu, W. & Feng, X. An improved satellite-based approach for estimating vapor pressure deficit from modis data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 119, 12–256, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD022118 (2014).

Barkhordarian, A., Saatchi, S. S., Behrangi, A., Loikith, P. C. & Mechoso, C. R. A recent systematic increase in vapor pressure deficit over tropical south america. Scientific reports 9, 15331, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51857-8 (2019).

Baldocchi, D. et al. Fluxnet: A new tool to study the temporal and spatial variability of ecosystem-scale carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy flux densities. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 82, 2415–2434, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(2001)082 (2001).

Yang, F. et al. Assessing the representativeness of the ameriflux network using modis and goes data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JG000627 (2008).

Novick, K. A. et al. The ameriflux network: A coalition of the willing. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 249, 444–456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.10.009 (2018).

Hersbach, H. et al. The era5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Fang, Z., Zhang, W., Brandt, M., Abdi, A. M. & Fensholt, R. Globally increasing atmospheric aridity over the 21st century. Earth’s future 10, e2022EF003019, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF003019 (2022).

Chu, H. et al. Representativeness of eddy-covariance flux footprints for areas surrounding ameriflux sites. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 301-302, 108350, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2021.108350 (2021).

Ficklin, D. L. & Novick, K. A. Historic and projected changes in vapor pressure deficit suggest a continental-scale drying of the united states atmosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 122, 2061–2079, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025855 (2017).

Sulman, B. N. et al. High atmospheric demand for water can limit forest carbon uptake and transpiration as severely as dry soil. Geophysical Research Letters 43, 9686–9695, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069416 (2016).

Gamelin, B. L. et al. Projected us drought extremes through the twenty-first century with vapor pressure deficit. Scientific Reports 12, 8615, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12516-7 (2022).

Chang, Q. et al. Earlier ecological drought detection by involving the interaction of phenology and eco-physiological function. Earth’s Future 11, e2022EF002667, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002667 (2023).

McDonald, J. M., Srock, A. F. & Charney, J. J. Development and application of a hot-dry-windy index (hdw) climatology. Atmosphere 9, 285, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos9070285 (2018).

Hiraga, Y. & Kavvas, M. L. Hydrological and meteorological controls on large wildfire ignition and burned area in northern california during 2017–2020. Fire 4, 90, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire4040090 (2021).

Thornton, M. et al. Daymet: Daily surface weather data on a 1-km grid for north america, version 4 r1. ORNL DAAC, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/2129 (2022).

Sadler, E. J. & Evans, D. E. Vapor pressure deficit calculations and their effect on the combination equation. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 49, 55–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1923(89)90062-2 (1989).

Ghanem, M. E., Kehel, Z., Marrou, H. & Sinclair, T. R. Seasonal and climatic variation of weighted vpd for transpiration estimation. European Journal of Agronomy 113, 125966, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2019.125966 (2020).

Thornton, P. E., Running, S. W. & White, M. A. Generating surfaces of daily meteorological variables over large regions of complex terrain. Journal of hydrology 190, 214–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(96)03128-9 (1997).

Thornton, P. E. et al. Gridded daily weather data for north america with comprehensive uncertainty quantification. Scientific Data 8, 190, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00973-0 (2021).

Thornton, P. E. & Running, S. W. An improved algorithm for estimating incident daily solar radiation from measurements of temperature, humidity, and precipitation. Agricultural and forest meteorology 93, 211–228, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(98)00126-9 (1999).

Thornton, P. E., Hasenauer, H. & White, M. A. Simultaneous estimation of daily solar radiation and humidity from observed temperature and precipitation: an application over complex terrain in austria. Agricultural and forest meteorology 104, 255–271, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(00)00170-2 (2000).

Kimball, J. S., Running, S. W. & Nemani, R. An improved method for estimating surface humidity from daily minimum temperature. Agricultural and forest meteorology 85, 87–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(96)02366-0 (1997).

Baldocchi, D., Valentini, R., Running, S., Oechel, W. & Dahlman, R. Strategies for measuring and modelling carbon dioxide and water vapour fluxes over terrestrial ecosystems. Global change biology 2, 159–168, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.1996.tb00069.x (1996).

Friedl, M. & Sulla-Menashe, D. Modis/terra + aqua land cover type yearly l3 global 500 m sin grid v061 [data set], https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12Q1.061 Accessed 2023-06-01 (2022).

AppEEARS Team. Application for extracting and exploring analysis ready samples (appeears) https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Accessed September 9, 2024. (2024).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future köppen-geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Scientific data 5, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.214 (2018).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future köppen-geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6396959 Dataset (2018).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the köppen-geiger climate classification. Hydrology and earth system sciences 11, 1633–1644, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007 (2007).

Xia, Y. et al. Continental-scale water and energy flux analysis and validation for the north american land data assimilation system project phase 2 (nldas-2): 1. intercomparison and application of model products. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016048 (2012).

Cosgrove, B. A. et al. Real-time and retrospective forcing in the north american land data assimilation system (nldas) project. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD003118 (2003).

Xia, Y. et al. NLDAS Primary Forcing Data L4 Hourly 0.125 × 0.125 degree V002, https://doi.org/10.5067/6J5LHHOHZHN4 Accessed: September 18, 2024 (2009).

Monteith, J. & Unsworth, M. Principles of environmental physics: plants, animals, and the atmosphere (Academic Press, 2013).

Junzeng, X., Qi, W., Shizhang, P. & Yanmei, Y. Error of saturation vapor pressure calculated by different formulas and its effect on calculation of reference evapotranspiration in high latitude cold region. Procedia Engineering 28, 43–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.01.680 (2012).

Running, S. W., Nemani, R. R. & Hungerford, R. D. Extrapolation of synoptic meteorological data in mountainous terrain and its use for simulating forest evapotranspiration and photosynthesis. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 17, 472–483, https://doi.org/10.1139/x87-081 (1987).

Corak, N. K. & Lowman, L. E. L. Land cover and climate informed vapor pressure deficit datasets derived from daymet https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.de74b0a457c74deca09f9a41afa03c8f (2025).

Entekhabi, D., Reichle, R. H., Koster, R. D. & Crow, W. T. Performance metrics for soil moisture retrievals and application requirements. Journal of Hydrometeorology 11, 832–840, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JHM1223.1 (2010).

Otkin, J. A. et al. Flash droughts: A review and assessment of the challenges imposed by rapid-onset droughts in the united states. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 99, 911–919, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0149.1 (2018).

Li, C. et al. Influence of vapor pressure deficit on vegetation growth in china. Journal of Arid Land 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-024-0077-0 (2024).

Anderson, M. C. et al. Evaluation of drought indices based on thermal remote sensing of evapotranspiration over the continental united states. Journal of Climate 24, 2025–2044, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3812.1 (2011).

Mahrt, L. & Ek, M. The influence of atmospheric stability on potential evaporation. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 23, 222–234, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1984)023 (1984).

Basara, J. B. et al. The evolution, propagation, and spread of flash drought in the central united states during 2012. Environmental Research Letters 14, 084025, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab2cc0 (2019).

Sanginés de Cárcer, P. et al. Vapor–pressure deficit and extreme climatic variables limit tree growth. Global Change Biology 24, 1108–1122, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13973 (2018).

Ibanez, T. et al. Altered cyclone–fire interactions are changing ecosystems. Trends in Plant Science 27, 1218–1230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2022.08.005 (2022).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the cru ts monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Scientific data 7, 109 (2020).

Information Systems and Wake Forest University. WFU High Performance Computing Facility, https://doi.org/10.57682/G13Z-2362 (2021).

Black, T. A. Ameriflux base ca-ca3 british columbia - pole sapling douglas-fir stand, ver. 6-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1480302 (2023).

Knox, S. Ameriflux base ca-dsm delta salt marsh, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1964085 (2023).

Wagner-Riddle, C. Ameriflux base ca-er1 elora research station, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1579541 (2021).

McCaughey, J., Pejam, M., Arain, M. & Cameron, D. Carbon dioxide and energy fluxes from a boreal mixedwood forest ecosystem in ontario, canada, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGRFORMET.2006.08.010 (2006).

Bergeron, O. et al. Comparison of carbon dioxide fluxes over three boreal black spruce forests in canada, https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2486.2006.01281.X (2006).

Peichl, M., Brodeur, J. J., Khomik, M. & Arain, M. A. Biometric and eddy-covariance based estimates of carbon fluxes in an age-sequence of temperate pine forests, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGRFORMET.2010.03.002 (2010).

Arain, M. A. Ameriflux base ca-tp2 ontario - turkey point 1989 plantation white pine, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246010 (2018).

Arain, M. A. & Restrepo-Coupe, N. Net ecosystem production in a temperate pine plantation in southeastern canada, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGRFORMET.2004.10.003 (2005).

Arain, M. A. Ameriflux base ca-tpd ontario - turkey point mature deciduous, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246152 (2018).

Yepez, E. A. Ameriflux base mx-aog alamos old-growth tropical dry forest, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1756414 (2020).

Yepez, E. A. & Garatuza, J. Ameriflux base mx-tes tesopaco, secondary tropical dry forest, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1767832 (2021).

Waldo, S. Ameriflux base us-act acton lake flux tower site, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1846660 (2022).

Moreo, M. Ameriflux base us-adr amargosa desert research site (adrs), ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1418680 (2018).

Leclerc, M. Ameriflux base us-akn savannah river site, ver. 6-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246141 (2023).

Olson, B. Ameriflux base us-alq allequash creek site, ver. 18-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1480323 (2024).

Billesbach, D., Bradford, J. & Torn, M. Ameriflux base us-ar1 arm usda unl osu woodward switchgrass 1, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246137 (2019).

Billesbach, D., Bradford, J. & Torn, M. Ameriflux base us-ar2 arm usda unl osu woodward switchgrass 2, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246138 (2019).

Torn, M. Ameriflux base us-arb arm southern great plains burn site- lamont, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246025 (2019).

Torn, M. Ameriflux base us-arc arm southern great plains control site- lamont, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246026 (2019).

Anderson, R. G. Ameriflux base us-ash ussl san joaquin valley almond high salinity, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1634880 (2020).

Anderson, R. G. Ameriflux base us-asl ussl san joaquin valley almond low salinity, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1617706 (2020).

Anderson, R. G. Ameriflux base us-asm ussl san joaquin valley almond medium salinity, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1617709 (2020).

Ouimette, A. P. et al. Carbon fluxes and interannual drivers in a temperate forest ecosystem assessed through comparison of top-down and bottom-up approaches, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGRFORMET.2018.03.017 (2018).

Hemes, K. S. et al. Assessing the carbon and climate benefit of restoring degraded agricultural peat soils to managed wetlands, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGRFORMET.2019.01.017 (2019).

Rey-Sanchez, C. et al. Ameriflux base us-bi2 bouldin island corn, ver. 17-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1419513 (2024).

Goldstein, A. Ameriflux base us-blo blodgett forest, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246032 (2019).

Meyers, T. Ameriflux base us-bo1 bondville, ver. 2-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246036 (2016).

Bernacchi, C. Ameriflux base us-bo2 bondville (companion site), ver. 2-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246037 (2016).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-bwa influx - nist turfgrass site, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2229153 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-bwb influx - montgomery county pasture site, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2229154 (2023).

Stoy, P. & Brevert, S. Ameriflux base us-cc1 coloma corn 1, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1865475 (2022).

Bowling, D., Kannenberg, S. & Anderegg, W. Ameriflux base us-cdm cedar mesa, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1865477 (2024).

Clark, K. Ameriflux base us-ced cedar bridge, ver. 7-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246043 (2016).

Phillips, C. L. & Huggins, D. Ameriflux base us-cf1 caf-ltar cook east, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1543382 (2022).

Huggins, D. Ameriflux base us-cf2 caf-ltar cook west, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1543383 (2021).

Huggins, D. Ameriflux base us-cf3 caf-ltar boyd north, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1543385 (2022).

Huggins, D. Ameriflux base us-cf4 caf-ltar boyd south, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1543384 (2022).

Bowling, D. Ameriflux base us-cop corral pocket, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246129 (2019).

Ewers, B., Bretfeld, M. & Pendall, E. Ameriflux base us-cpk chimney park, ver. 2-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246150 (2016).

Noormets, A. Ameriflux base us-crk davy crockett national forest, ver. 5-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2204055 (2024).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs1 central sands irrigated agricultural field, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1617710 (2023).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs2 tri county school pine forest, ver. 5-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1617711 (2023).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs3 central sands irrigated agricultural field, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1617713 (2023).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs4 central sands irrigated agricultural field, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1756417 (2023).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs5 central sands irrigated agricultural field, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1846663 (2022).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs6 central sands irrigated agricultural field, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001297 (2023).

Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-cs8 central sands irrigated agricultural field, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001298 (2023).

Novick, K. Ameriflux base us-cst crossett experimental forest, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1902275 (2022).

Oishi, A. C. Ameriflux base us-cwt coweeta, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1671890 (2020).

Duff, A. & Desai, A. Ameriflux base us-dfc us dairy forage research center, prairie du sac, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1660340 (2023).

Duff, A., Desai, A. & Risso, V. P. Ameriflux base us-dfk dairy forage research center - kernza, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1825937 (2021).

DuBois, S. et al. Using imaging spectroscopy to detect variation in terrestrial ecosystem productivity across a water-stressed landscape, https://doi.org/10.1002/EAP.1733 (2018).

Clark, K. Ameriflux base us-dix fort dix, ver. 2-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246045 (2016).

Oishi, C., Novick, K. & Stoy, P. Ameriflux base us-dk1 duke forest-open field, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246046 (2018).

Oishi, C., Novick, K. & Stoy, P. Ameriflux base us-dk2 duke forest-hardwoods, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246047 (2018).

Oishi, C., Novick, K. & Stoy, P. Ameriflux base us-dk3 duke forest - loblolly pine, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246048 (2018).

Arias-Ortiz, A. & Baldocchi, D. Ameriflux base us-dmg dutch slough marsh gilbert tract, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1964086 (2024).

Hinkle, C. R. & Bracho, R. Ameriflux base us-dpw disney wilderness preserve wetland, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1562387 (2019).

McKinney, T. Ameriflux base us-ea4 eaa field research park woodland, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2315767 (2024).

McKinney, T. Ameriflux base us-ea5 uvalde ranch mesquite woodland, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2204056 (2024).

McKinney, T. Ameriflux base us-ea6 camp wood shield ranch oak savannah, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2315768 (2024).

Oikawa, P. Ameriflux base us-edn eden landing ecological reserve, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1543381 (2020).

Starr, G. & Oberbauer, S. Ameriflux base us-elm everglades (long hydroperiod marsh), ver. 4-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246118 (2016).

Starr, G. & Oberbauer, S. Ameriflux base us-esm everglades (short hydroperiod marsh), ver. 5-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246119 (2016).

Starr, G. & Oberbuer, S. F. Ameriflux base us-evm everglades saltwater intrusion marsh, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2229155 (2024).

Dore, S. & Kolb, T. Ameriflux base us-fmf flagstaff - managed forest, ver. 6-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246050 (2019).

Dore, S. & Kolb, T. Ameriflux base us-fuf flagstaff - unmanaged forest, ver. 6-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246051 (2019).

Dore, S. & Kolb, T. Ameriflux base us-fwf flagstaff - wildfire, ver. 8-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246052 (2019).

Massman, B. Ameriflux base us-gbt glees brooklyn tower, ver. 1-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1375200 (2016).

Spence, C. Ameriflux base us-gl1 stannard rock, ver. 3-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2204057 (2024).

Frank, J. M., Massman, W. J., Ewers, B. E., Huckaby, L. S. & Negrón, J. F. Ecosystem CO2/H2O fluxes are explained by hydraulically limited gas exchange during tree mortality from spruce bark beetles, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JG002597 (2014).

Hadley, J. & Munger, J. W. Ameriflux base us-ha2 harvard forest hemlock site, ver. 12-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246060 (2024).

Forsythe, J. D., O’Halloran, T. L. & Kline, M. A. An eddy covariance mesonet for measuring greenhouse gas fluxes in coastal south carolina, https://doi.org/10.3390/DATA5040097 (2020).

O’Halloran, T. Ameriflux base us-hb4 minim creek brackish impoundment, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001299 (2023).

Kelsey, E. & Green, M. Ameriflux base us-hbk hubbard brook experimental forest, ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1634881 (2023).

Hollinger, D. Ameriflux base us-ho1 howland forest (main tower), ver. 9-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246061 (2024).

Hollinger, D. Ameriflux base us-ho2 howland forest (west tower), ver. 6-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246062 (2024).

Hollinger, D. Ameriflux base us-ho3 howland forest (harvest site), ver. 2-1, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1246063 (2016).

Arias-Ortiz, A., Szutu, D., Verfaillie, J. & Baldocchi, D. Ameriflux base us-hsm hill slough marsh, ver. 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1890483 (2024).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-ina influx - cemetery turfgrass tower, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001300 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-inb influx - golf course, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001301 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-inc influx - downtown indianapolis (site-3), ver. 2-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/1987603 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-ind influx - agricultural site east near pittsboro, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001302 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-ine influx - agricultural site west near pittsboro, ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001303 (2023).

Forsythe, B. R., Horne, J. & Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-ing influx - wayne twp comm (site-7), ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001305 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-ini influx - agricultural site east of indianapolis (site-9a), ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001306 (2023).

Davis, K. Ameriflux base us-inj influx - agricultural site east of indianapolis (site-9b), ver. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.17190/AMF/2001307 (2023).