Abstract

The advancement of artificial intelligence has spurred progress across diverse scientific fields, with deep learning techniques enhancing autonomous driving and vessel detection applications. The training of deep learning models relies on the construction of datasets. We present a tri-band (visible, short-wave infrared, long-wave infrared) vehicle and vessel dataset for object detection applications and multi-band image fusion. The dataset consists of thousands of images with JPG and PNG formats, and information including acquisition dates, locations, among others. The features of the dataset are time synchronization and field-of-view consistency. About 60% of the dataset has been manually labeled with object instances to train and evaluate well-established object detection algorithms. After training with YOLOv8 and SSD object detection algorithms, all models have mAP values above 0.6 at an IoU threshold of 0.5, which indicates good recognition performance for this dataset. In addition, a preliminary validation of wavelet-based multi-band image fusion was performed. As far as we know, the dataset is the first publicly available tri-band optical image dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

In the field of computer vision, object detection is one of the fundamental tasks, forming the basis for other image understanding operations1. Object detection algorithms are widely used for various domains such as traffic monitoring2, automatic driving3, ship monitoring and tracking4. Datasets play a crucial role in training and validating algorithms for object detection. With the emergence of deep learning techniques5, there are demands for more datasets. As a result, numerous new datasets have recently been created and publicly released. Currently, there are several widely used datasets in the field of deep learning, such as LSUN6, ImageNet7, MSCOCO8, among others.

The datasets used for detection are usually categorized as9 pedestrian detection, face detection, everyday object detection, and vehicle detection. Many datasets of vehicles and ships have been introduced to help improve the detection performance of algorithms. Most datasets were built with VIS (visible light) band images. Some of the well-known VIS datasets for vehicle and ship detection include SeaShips10, MARVEL11, GLSD12, ShipYOLO13, Mcships14, MASATI15. As for special weather conditions, FoggyShipInsseg16 handles the scarcity of ocean data in foggy weather and SMART-Rain17 enriches existing datasets that lack representative data from rainy weather. Considering different application scenarios, CODA18 is the first real-world road corner case dataset, AD4CHE19 is a dataset for congested highways and UA-DETRAC20 is a dataset for multi-object tracking. Since VIS images are usually dominated by light conditions, LWIR (long-wave infrared) showing thermal information has the flexibility throughout the day. LWIR images are supplied in many datasets. The NSAVP21, RGBT23422, KAIST23, Drone Vehicle24, FLIR ADAS25, and VAIS26 datasets were introduced with VIS and LWIR images. These datasets integrate visible and thermal spectrum data that have been proven to be effective in boosting detection. As for scenes with insignificant temperature differences, SWIR (short-wave infrared) supplies more information in addition to VIS and LWIR, with a strong ability to penetrate haze and smog. So SWIR images are also supplied in some datasets. The RGB-SWIR image dataset27, SMD28, and HSI-Drive29 datasets were introduced with VIS and SWIR (short-wave infrared) images. These datasets can achieve better object detection performance under hazy conditions. So far as we know, no tri-band dataset (VIS, SWIR, LWIR) has been published yet to combine the advantages of the three bands.

For these multi-band datasets, the images in each band of the dataset should meet time synchronization and field-of-view consistency. Multi-band datasets are also widely used in image fusion to reduce uncertainties in the image processing chain, which is crucial for enhancing image fusion30. This necessitates a cross-sectional comparison of the data in each band after introducing multi-bands, with the precondition that the data in each band satisfy time synchronization and field-of-view consistency. The NSAVP dataset introduces the concept of camera time synchronization21, ensuring that the VIS images and LWIR images of corresponding targets appear at the same moment. Its highlight lies in utilizing time synchronization to eliminate some data interference caused by temporal factors.

Although many datasets have been introduced for object detection on vehicles and vessels, there are many challenges in this field:

-

Single application band and non-diversified data distribution. Several vehicle and vessel datasets only comprise VIS images, which limits their use during night-time and foggy weather. For example, SMART-Rain17 only adapts well to rainy conditions. Several vehicles and vessels datasets only comprise SWIR images, and the RGB-SWIR image dataset27 and FoggyShipInsseg16 only perform well in foggy weather. LWIR imaging may be affected in environments where temperature differences are minimal, which limits LWIR datasets in certain scenarios. For example, the IR vehicle recognition dataset31 merely performs well at night. Limiting the dataset to a single scenario or weather restricts its applicability across various scenarios, such as object detection across multiple scenes and detection of multiple object categories.

-

Time is not synchronized and field of view is inconsistent. Many multi-band datasets do not meet the time synchronization and field-of-view consistency, which leads to the reduction of the relevance of objects in different bands, and the effect of multi-band data in image fusion is not ideal. Ensuring time synchronization and field-of-view consistency among data groups during dataset construction can eliminate data interference caused by time and field-of-view factors.

We present the Tri-band (VIS, SWIR, LWIR) Vehicle and Vessel Dataset. To facilitate research on diverse issues, such as the weather and scenarios on object detection accuracy, the tri-band optical image dataset records crucial information, including the shooting date, collection location, lighting status and weather conditions. The tri-band optical image dataset, which includes various scenarios (such as urban roads, intersections, rural roads, harbors, islands, and coastal lands) and various weather conditions (such as sunny, cloudy, rainy, snowy, and foggy days), aims to increase data distribution for various tasks.

The dataset comprises thousands of images and all images are collected in public. To the best of our knowledge, the tri-band optical image dataset is the first publicly available tri-band optical image dataset for detecting vehicles and vessels. The dataset has the great potential to enable several research activities, such as (1) the application range of tri-band dataset in object detection tasks, (2) the relationship of different band and object detection precision, (3) the impact of time synchronization and field-of-view consistency for image fusion.

Methods

Acquisition equipment

Our image acquisition equipment consists of three cameras and an image capture platform.

The three cameras are shown in Fig. 1. The VIS camera is a common industrial visible light camera. The SWIR camera is a homemade Indium Gallium Arsenide uncooled infrared camera during the acquisition process developed by our team. Meanwhile, the LWIR camera is a vanadium oxide uncooled infrared camera (LT640, IRAY). These three cameras are connected to a computer during the acquisition process. The specific parameters for each camera are detailed in Table 1. At the initial stage of image acquisition, the focal length of the lenses of all three cameras was 50 mm, but the FOV (field of view) of the three cameras varies due to the different sensor sizes. In addition, due to the different aspect ratios of the sensors of the three cameras, their FOVs cannot be identical. To achieve consistent FOVs, the DFOV (diagonal field of view) is used to ensure near-identical FOVs. We obtain the sizes of the DFOVs of the three cameras according to the formula: DFOV = 2arctan(d/2f), where f is the focal length of the lens, and d is the diagonal size of the camera sensor. Then, taking the existing 50 mm and 100 mm focal length SWIR lenses as two references, we calculated two sets of required lens focal lengths to maintain the same DFOV for the three cameras. Finally, by comparing with the existing lens focal lengths in the market, we designed two sets of lens sets, SET_F and SET_N, so that the three cameras have almost the same DFOV and can adapt to targets at different distances. The specific parameters are shown in Table 2. The SET_F lens set is adapted to targets above 200 m, while the SET_N lens set is adapted to targets within 200 m.

The image capture platform utilized is a tripod equipped with three 2-axis stages, which facilitates the precise control of the azimuth and pitch angles during the capture process, as shown in Fig. 2. The 2-axis stages are capable of operating over an azimuth angle range from −180° to +180° and a pitch angle from −90° to +90°. To ensure that the three sets of images present a consistent FOV, the FOV centers (centers of the fields of view) of the three cameras must align perfectly. To achieve this, the three cameras can be aligned in the same direction by adjusting the azimuth and pitch angles of the platform before collecting data, thus ensuring that the FOV centers coincide.

To ensure that FOV centers of the three cameras mounted on the same rigid support structure are accurately aligned, we performed alignment error correction and accuracy evaluation. Since the shooting target is more than 50 meters away from the cameras, significantly larger than the 5 cm spacing between cameras, the angle between any two cameras is less than 0.001°, which has a negligible effect on the FOV alignment. We further verified the alignment accuracy by placing a high-precision calibration plate at the target location and using the three cameras to simultaneously capture images of the calibration plate. The calculation results show that the alignment error between the FOV centers of the three cameras and the center of the calibration plate is less than 0.001°, which is well below the system’s required accuracy. Repeated experiments show that the alignment error of the system is within acceptable limits and has no significant impact on subsequent data acquisition and analysis.

Dataset building process

The dataset generation pipeline comprises five stages: scene selection, video capture, frame extraction & frame synchronization, object annotation, and dataset generation.

Scene selection

The vehicle acquisition scenarios were selected as four different types of road environments, including traffic signal intersections, ordinary intersections, rural roads, and urban streets. Similarly, for the vessel acquisition scenarios, three varied types of oceanic settings were chosen, including port area, coastal area and reef area. The main targets of our captures are different types of vehicles and vessels.

Different lighting conditions are likewise one of the factors to be considered in the construction of datasets. Taking into account the lighting conditions of frontlight, backlight, and sidelight, the acquisition times were chosen to be at different times of the day32,33,34. For example, at a site facing east, collections were conducted with morning light conditions as front-lighting, midday light conditions as side-lighting, and afternoon light conditions as back-lighting. Likewise, we captured videos under varying weather scenarios, including sunny, rainy, snowy, and more.

Video capture

Irrespective of whether a lens set with a focal length of 50 mm or the two lens sets, SET_F and SET_N, are employed, the FOV centers of the three cameras must be adjusted to overlap when images are captured. Such adjustment is essential to ensure consistency in the FOV across the three sets of images. Prior to image acquisition, a point within the scene is initially designated as the FOV center. Thereafter, the pitch and azimuth angles of the acquisition platform are calibrated to align the FOV centers of the three cameras with this designated point, as depicted in Fig. 3.

During image acquisition, the acquisition modes of the three cameras are activated simultaneously when the target appears in the surveillance FOV. Conversely, the acquisition modes are deactivated when the target exits the surveillance FOV. Finally, the detailed status of each set of data, including the date of shooting, collection location, lighting conditions, and weather conditions, is recorded.

Frame extraction & frame synchronization

In a set of consecutive image sequences, changes in image features between adjacent frames are not really significant. Although many current datasets retain all frames to train the detection model, this approach does not address the limited feature distribution. So, in order to include more image features with less amount of data, we perform frame extraction and frame synchronization on consecutive frames35.

First, before extracting the frames, it must be ensured that the first frames of the three image sequences (VIS, SWIR, LWIR) are time synchronized. This necessitates a manual calibration process. The first-frame image with the latest time among the three is set as the reference. Then, two fixed points in the scene in the direction of the target’s movement are selected. The relative positions of the target in the three images are made consistent by calculating the ratio of the distances between the target and these two points in each set of images. This process ensures the temporal consistency of the three images, as shown in Fig. 4. To ensure that the first images of the three sequences are synchronized in time, the images before the reference time in each image sequence are removed. By observing the changes in image features in consecutive frames, the changes in features between adjacent frames were not significant, which contributed little to the performance improvement of the trained model. Therefore, a program was designed to process consecutive frames, aiming to extract the corresponding frames from the sequence in batches based on certain time intervals. The time interval was set to extract 1 image every 20 frames by observation and comparison. This approach not only compresses the volume of the dataset but also preserves the essential image characteristics to the greatest extent possible. By this method, a 250-frame image sequence can be compressed into 12 frames, which improves the training speed of the model. Finally, a comparative analysis and validation of the processed three image sequences were performed to ensure that the three sets of images, which should be time-synchronized theoretically, were synchronized.

Object annotation

For the labeling of the dataset, different users may have different requirements. In order to facilitate users to use our dataset more comprehensively, the dataset provides all raw data to users. To validate the usability of the dataset, a portion of the data is annotated to validate the dataset using algorithms, and at the same time, this part of the labeled data is also provided to the users.

The objects in the dataset are labeled using the standard bounding box format of the YOLO dataset. The image annotation is performed using the tools provided on the ROBOFLOW website. The standard bounding box is denoted as (n, xc, yc, w, h), where n denotes the category of the annotated object, (xc, yc) denotes the scaled value of the center point with respect to the size of the image, ranging from 0 to 1, and (w, h) denotes the scaled value of the width and height of the bounding box with respect to the size of the image. Finally, the labeled data are double-checked by the authors to ensure that all targets have been labelled.

Dataset generation

The dataset images are mainly acquired using the SET_F and SET_N lens sets, with field-of-view consistency. Earlier data acquired with the 50-mm lens set are also retained to enrich the data and to increase the robustness of the dataset, corresponding to data before August 27, 2023. All images in the dataset have their FOV centers coincide for the three spectral bands, which is a necessary condition to satisfy field-of-view consistency.

All image files are renamed to ensure consistency in the naming of the corresponding frames of the three image sequences. A dataset generation program is then designed to systematically organize the data into corresponding subdirectories according to our organizational criteria, which are described in detail below. Subsequently, these subdirectories are arranged into their respective parent folders according to the organizational criteria. Finally, the corresponding data can be found via a dataset log.

Data Records

The dataset is available on figshare36 and on the official website of the Center for Optics Research and Engineering, Shandong University37. The dataset contains 923 tri-band (visible, SWIR, LWIR) vehicle datasets (2,769 single images) and 450 tri-band ship datasets (1,350 single images), each consisting of three images taken simultaneously. Since its release, this dataset has been used for scientific research by more than 50 research institutions, such as the University of Melbourne, Tsinghua University, Zhejiang University, University of Electronic Science and Technology, and others.

Folder structure

Users have access to two different types of files in the dataset: annotation files and raw image files. Both files contain tri-band image data; image files in JPG format for the VIS and LWIR image datasets and PNG format for the SWIR image dataset. The annotation files are in TXT format and conform to the YOLO dataset specification. The top-level directory of the dataset is divided into two main subdirectories: raw_data and labeled_data.

The raw_data subdirectory contains raw, unprocessed images of vehicles and vessels, including the vehicle dataset and vessel dataset subdirectories, as well as the shooting log. The structure of these two subdirectories is shown in Fig. 5a. Each subdirectory is named according to the date of data acquisition and contains all the image data acquired at different locations on that day. The dataset shooting log details the type of data (vehicle or vessel), time and location of acquisition, lighting conditions and weather conditions.

The labeled_data subdirectory contains data that has been annotated. It similarly comprises VIS, SWIR, and LWIR subdirectories, which are organized in a uniform manner, as illustrated in Fig. 5b. Each of these subdirectories further contains two additional subfolders: image and label. The label subfolder is dedicated to storing annotation files featuring standard bounding boxes in TXT format, while the image subfolder contains the image files that correspond to these annotations.

Data statistics

The primary subjects of this dataset are vehicles in motion on terrestrial roadways and maritime vessels observed from a sea-skimming perspective.

Figure 6 shows the classification statistics for the vehicle dataset. To enhance the versatility of the dataset in different tasks, the collection locations of the dataset were chosen to be traffic signal intersections, ordinary intersections, rural roads, and urban streets, as is shown in Fig. 6a. Images show different properties in different lighting conditions, therefore, they were captured under various lighting conditions (frontlight, backlight, and sidelight), and the way to realize this step was to take them both in the morning and in the afternoon at the same location, and this information is shown in Fig. 6b. Additionally, to fortify the dataset’s generalizability and robustness, image data were collected under different weather conditions, which is shown in Fig. 6c.

Figure 7 outlines the categorical statistics for the marine vessel dataset. To enhance the dataset’s versatility in diverse tasks, the collection spanned multiple geographical locales, including port area, coastal area and reef area, as indicated in Fig. 7a. Furthermore, the dataset encompasses a variety of marine vessel types, as shown in Fig. 7b, thereby enhancing its generalizability. The targets are also categorized into nearshore and farshore targets, as shown in Fig. 7c.

Properties

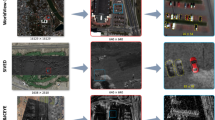

The two main features of this dataset are time synchronization and field-of-view consistency. Through the selection of lenses for the three cameras and the adjustment of the acquisition platform, the tri-band image essentially meets the requirement of field-of-view consistency, as shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, through frame extraction and frame synchronization operations on the tri-band image, the temporal synchronization of the three images within the tri-band image is ensured, as shown in Fig. 4. These two features are mainly used for multi-band image fusion. The purpose of image fusion is to create a fused image by integrating dominant information from multiple images so that the fused image contains more information. Image fusion requires image alignment. In the process of image alignment, the source image is mapped and the equivalent image is matched based on key features. In order to reduce the computational cost, some similarity should be maintained between different images. In constructing the dataset, the tri-band images should ensure both the richness of background information and a certain degree of similarity.

The images in the three bands in this dataset contain different feature information. Figure 8 shows some examples of snowy day acquisitions, VIS images can provide the most intuitive details for computer vision tasks, i.e., they can provide detailed messages about the colours, textures, etc. in the scene. Although SWIR images have less detailed information compared to visible light images, they reflect richer background information than visible light images due to their higher fog-transparency capability. The LWIR images can show the temperature information in the scene, as shown in the LWIR image in Fig. 8. Since the temperature of the front of the vehicle is slightly lower than that of the rear of the vehicle during driving, it is easy to determine the direction of vehicle driving.

Figure 9a shows some examples of images under good lighting conditions. At this point, the VIS image presents the clearest ship and contains colour and other detailed information. Infrared band image can show the outline of a ship, but due to their lack of colour information, the ship in the image has the same colour as its surroundings, making it difficult to distinguish the target from the background. Thus, the VIS image is imaged best in the scene shown in Fig. 9a. Some illustrations of acquisitions in the backlight state are shown in Fig. 9b. While in the backlight condition, the VIS image is almost impossible to observe the distant ships due to the sunlight. In contrast, the infrared band is less affected by the state of light, but at longer distances, LWIR images will only slightly show the outline of the ship, whereas SWIR images will show a clearer outline. Therefore, the SWIR image is best imaged in the scene shown in Fig. 9b.

Technical Validation

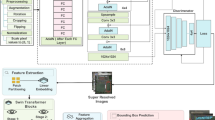

YOLOv8 algorithm validation

The YOLOv8 target detection algorithm was employed to train the labeled data. The labeled datasets for each of the three bands were trained and validated separately, with the SWIR image dataset comprising 611 training images and 261 validation images, the LWIR image dataset consisting of 990 training images and 424 validation images, and the VIS image dataset including 1326 training images and 567 validation images. Considering the varying size of the targets contained in the sample images, we normalized the sample size to 640 × 640 to make the detection process balance the requirements of real-time and accuracy. This size allows the model to be truly applicable to edge devices without destroying too much useful information in the image38. The pre-trained model for YOLOv8 was obtained from the official source “yolov8n.pt”. The configuration parameters for the training environment are detailed in Table 3, while the Hyperparametric parameters for the training process are presented in Table 4.

During the training process, the epoch number of all three models is 150, the usage of training memory is about 2 G, and the total training and validation time for each of the three models is less than 5 hours. After 150 rounds of training, the final performance metrics are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 10. mAP50 refers to the average precision of the models when the IoU threshold is 0.5, and mAP50–95 refers to the average precision of the models when the IoU threshold ranges from 0.5 to 0.95. The mAP50 of all three models exceeds 0.8, and the mAP50–95 is around 0.5, indicating that the models are capable of accurately detecting and localizing targets in most cases. Additionally, the precision and recall of all three models exceed 0.8, and the maximum value of the F1 score curve is also above 0.8, indicating that the models exhibit good performance.

To visually and easily validate our dataset, the detection performance of the model was analyzed using the confusion matrix. The rows and columns of the confusion matrix represent the true and predicted categories respectively. The values in the diagonal region of the normalized confusion matrix represent the proportion of correctly predicted categories and the values in the other regions represent the proportion of incorrectly predicted categories. Figure 11 shows the confusion matrices and the normalized confusion matrices for the above three models.

As can be seen in Fig. 11, except for the background prediction, the data in the diagonal region of the confusion matrices of the three models are the largest among the data in the corresponding rows and columns, and the data in the diagonal region of the normalized confusion matrices is the largest among the data in the corresponding columns. This suggests that our three models perform better in correctly predicting the target categories. However, the three models also exhibited certain false-negative rates (i.e., misclassifying targets as background categories) and false-positive rates. Given the above characteristics, the reasons for observing the performance of the three models are explained from an interpretable perspective. Although the single-stage detection algorithms, such as those represented by the YOLO series, are superior to many object detection methods, the two-stage detection algorithm is superior to the YOLO algorithm for images with a high proportion of background information and a high number of small objects39. Since the images in the dataset do not remove the background information and the dataset involves richer scenes, the proportion of background information in the dataset is high, so the model will have some false negatives and false positives.

The results show that the model trained on this dataset has good recognition ability as shown in Fig. 12. At the same time, thanks to its own characteristics (e.g., high percentage of background information, etc.), this dataset can validate the performance of some algorithms, which greatly broadens the generalizability of these algorithms.

SSD Algorithm validation

The SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) constitutes a feature pyramid-based multi-scale object detection framework. The model was trained on annotated datasets from three bands. The VIS image dataset consists of 1457 training images, 162 validation images, and 180 test images. The SWIR image dataset consists of 705 training images, 79 validation images, and 88 test images. The LWIR image dataset consists of 1144 training images, 128 validation images, and 142 test images. All input samples were normalized to 640 × 640 resolution. The architecture was initialized with publicly available SSD weights (ssd_weights. pth) from official repositories. The configuration parameters for the training environment are detailed in Table 6, while the hyperparametric parameters for the training process are presented in Table 7.

During the training process, all three models were trained for 100 epochs, the training memory usage was approximately 6 GB, and each model’s total training and validation time is under 10 hours. The final performance metrics are shown in Table 8. The mAP of all three models is greater than 0.7. In the quantitative evaluation with score_threhold of 0.5, the precision, recall, and F1 scores of all three models are greater than 0.6, which indicates that the models perform well.

Tri-band image fusion based on wavelet fusion

To further validate the potential application of this dataset in multi-band image fusion, we conducted fusion experiments on three-band images using a wavelet transform-based image fusion method. The wavelet transform, as a multi-scale analysis tool, extracts image details and fuses them at different scales, enabling source image complementarity. Low-frequency components are fused via weighted averaging to preserve structure, while high-frequency components are fused using local energy maximization to enhance details, followed by wavelet inversion for reconstruction40.

Tri-band image fusion can effectively complement the missing information in single-band images, especially in complex scenes. The fused image can provide more comprehensive target information. As shown in Fig. 13, in infrared images, some detailed information (e.g., traffic light countdown) cannot be clearly presented, while fusing visible light images supplements this information. As shown in Fig. 14, in the visible light and long-wave infrared images, the cargo ships on the sea surface cannot be clearly presented, and fusing short-wave infrared images supplements these details.

Although the fused image demonstrates the advantage of complementary information in visualization, it can also be observed that some high-frequency information is lost in the fused image. This phenomenon may be due to the limitations of current wavelet fusion methods. Existing multi-band image fusion algorithms require further development to improve their adaptability and accuracy. The release of this dataset will provide essential data support for these studies and advance multi-band image fusion technology.

Usage Notes

This dataset is available free of charge to any individual or organization. If this dataset helps, we would appreciate it if the users could support our work by sending information about their organization, use of the dataset, and contact information to hwgztd@sdu.edu.cn. Suggestions and co-operations are also welcome.

The dataset was collected in a variety of environments, which ensures that the dataset is generalizable and robust. With the generalization capabilities of deep learning, it is then possible to apply the trained object detection models to these scenarios as well as other environments. In addition, users can utilize this dataset for multi-band image fusion. This dataset provides raw data to users, who can perform their own cropping, labeling, and other operations on the data according to their needs to accomplish their intended tasks.

Code availability

The dataset was labeled using the data labeling tool available at https://universe.roboflow.com/. The dataset was trained using the YOLOv8 algorithm model available at https://docs.ultralytics.com/. The dataset was trained using the SSD algorithm model on https://github.com/bubbliiiing/ssd-pytorch.

References

Salari, A., Djavadifar, A., Liu, X. & Najjaran, H. Object recognition datasets and challenges: A review. Neurocomputing 495, 129–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2022.01.022 (2022).

Jain, N. K., et al. Soft Computing: Theories and Applications. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (Springer Singapore, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4032-5 (2020).

Yang, M. Research on Vehicle Automatic Driving Target Perception Technology Based on Improved MSRPN Algorithm. Journal of Computational and Cognitive Engineering 1, 147–151, https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewJCCE20514 (2022).

Sanchez-Iborra, R., G. Liaño, I., Simoes, C., Couñago, E. & Skarmeta, A. F. Tracking and Monitoring System Based on LoRa Technology for Lightweight Boats. Electronics 8, 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8010015 (2018).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 60, 84–90, https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386 (2017).

Kramberger, T. & Potočnik, B. LSUN-Stanford Car Dataset: Enhancing Large-Scale Car Image Datasets Using Deep Learning for Usage in GAN Training. Applied Sciences 10, 4913, https://doi.org/10.3390/app10144913 (2020).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 248–255 https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2009.5206848 (2009).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13, 740–755, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48 (2014).

Razakarivony, S. & Jurie, F. Vehicle detection in aerial imagery: A small target detection benchmark. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 34, 187–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2015.11.002 (2016).

Shao, Z., Wu, W., Wang, Z., Du, W. & Li, C. SeaShips: A Large-Scale Precisely Annotated Dataset for Ship Detection. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 20, 2593–2604, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmm.2018.2865686 (2018).

Gundogdu, E., Solmaz, B., Yücesoy, V. & Koc, A. Marvel: A large-scale image dataset for maritime vessels. Computer Vision–ACCV 2016: 13th Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, November 20–24, 2016, Revised Selected Papers, Part V 13, 165–180, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54193-8_11 (2016).

Shao, Z. et al. GLSD: a global large-scale ship database with baseline evaluations. Geo-Spatial Information Science, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2024.2416896 (2025).

Han, X. et al. ShipYOLO: An Enhanced Model for Ship Detection. Journal of Advanced Transportation 2021, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1060182 (2021).

Zheng, Y., & Zhang, S. Mcships: A large-scale ship dataset for detection and fine-grained categorization in the wild. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/icme46284.2020.9102907 (2020).

Gallego, A.-J., Pertusa, A. & Gil, P. Automatic Ship Classification from Optical Aerial Images with Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sensing 10, 511, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10040511 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. IRDCLNet: Instance Segmentation of Ship Images Based on Interference Reduction and Dynamic Contour Learning in Foggy Scenes. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 32, 6029–6043, https://doi.org/10.1109/tcsvt.2022.3155182 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Smart-rain: A degradation evaluation dataset for autonomous driving in rain. 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 9691–9698, https://doi.org/10.1109/iros55552.2023.10342015 (2023).

Li, K. et al. Coda: A real-world road corner case dataset for object detection in autonomous driving. European Conference on Computer Vision, 406–423 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19839-7_24 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. The AD4CHE Dataset and Its Application in Typical Congestion Scenarios of Traffic Jam Pilot Systems. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 8, 3312–3323, https://doi.org/10.1109/tiv.2023.3260902 (2023).

Wen, L. et al. UA-DETRAC: A new benchmark and protocol for multi-object detection and tracking. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 193, 102907, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cviu.2020.102907 (2020).

Carmichael, S. et al. Dataset and Benchmark: Novel Sensors for Autonomous Vehicle Perception. The International Journal of Robotics Research 44, 355–365, https://doi.org/10.1177/02783649241273554 (2025).

Li, C., Liang, X., Lu, Y., Zhao, N. & Tang, J. RGB-T object tracking: Benchmark and baseline. Pattern Recognition 96, 106977, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2019.106977 (2019).

Choi, Y. et al. KAIST Multi-Spectral Day/Night Data Set for Autonomous and Assisted Driving. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 19, 934–948, https://doi.org/10.1109/tits.2018.2791533 (2018).

Sun, Y., Cao, B., Zhu, P. & Hu, Q. Drone-Based RGB-Infrared Cross-Modality Vehicle Detection Via Uncertainty-Aware Learning. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 32, 6700–6713, https://doi.org/10.1109/tcsvt.2022.3168279 (2022).

Eltahan, M. & Elsayed, K. Enhancing Autonomous Driving By Exploiting Thermal Object Detection Through Feature Fusion. International Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems Research 22, 146–158, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13177-024-00385-5 (2024).

Zhang, M. M., Choi, J., Daniilidis, K., Wolf, M. T., & Kanan, C. VAIS: A dataset for recognizing maritime imagery in the visible and infrared spectrums. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 10–16, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvprw.2015.7301291 (2015).

Yu, B., Chen, Y., Cao, S.-Y., Shen, H.-L. & Li, J. Three-Channel Infrared Imaging for Object Detection in Haze. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 71, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1109/tim.2022.3164062 (2022).

Prasad, D. K., Rajan, D., Rachmawati, L., Rajabally, E. & Quek, C. Video Processing From Electro-Optical Sensors for Object Detection and Tracking in a Maritime Environment: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 18, 1993–2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/tits.2016.2634580 (2017).

Basterretxea, K., Martínez, V., Echanobe, J., Gutiérrez–Zaballa, J., & Del Campo, I. HSI-drive: A dataset for the research of hyperspectral image processing applied to autonomous driving systems. 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), 866–873, https://doi.org/10.1109/IV48863.2021.9575298 (2021).

Sara, D., Mandava, A. K., Kumar, A., Duela, S. & Jude, A. Hyperspectral and multispectral image fusion techniques for high resolution applications: a review. Earth Science Informatics 14, 1685–1705, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-021-00621-6 (2021).

Kang, Q., Zhao, H., Yang, D., Ahmed, H. S. & Ma, J. Lightweight convolutional neural network for vehicle recognition in thermal infrared images. Infrared Physics & Technology 104, 103120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2019.103120 (2020).

Li, Y., Wang, Y., Xu, D., Zhang, J. & Wen, J. An Improved Mask RCNN Model for Segmentation of ‘Kyoho’ (Vitis labruscana) Grape Bunch and Detection of Its Maturity Level. Agriculture 13, 914, https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13040914 (2023).

Li, J., Liu, Z. & Wang, D. A Lightweight Algorithm for Recognizing Pear Leaf Diseases in Natural Scenes Based on an Improved YOLOv5 Deep Learning Model. Agriculture 14, 273, https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020273 (2024).

Li, T. et al. PeachYOLO: A Lightweight Algorithm for Peach Detection in Complex Orchard Environments. IEEE Access 12, 96220–96230, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3411644 (2024).

Suo, J. et al. HIT-UAV: A high-altitude infrared thermal dataset for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-based object detection. Scientific Data 10, 227, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02066-6 (2023).

Zhao, G. et al. Tri-band Vehicle and Vessel Datasets. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27000481 (2025).

Tri-band Vehicle and Vessel Datasets. Center for Optics Research and Engineering, Shandong University, http://www.gxzx.sdu.edu.cn/info/1133/3181.htm (2025).

Li, Y., Fan, Q., Huang, H., Han, Z. & Gu, Q. A Modified YOLOv8 Detection Network for UAV Aerial Image Recognition. Drones 7, 304, https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7050304 (2023).

Nie, H., Pang, H., Ma, M. & Zheng, R. A Lightweight Remote Sensing Small Target Image Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8. Sensors 24, 2952, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24092952 (2024).

Pajares, G. & De La Cruz, J. M. A wavelet-based image fusion tutorial. Pattern recognition 37, 1855–1872, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2004.03.010 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by “The Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (2082019012)”, “Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022MF323, ZR2022LLZ002)”, “Key R&D Plan of Shandong Province (2020JMRH0101)”, “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2021JCG018)”, “Opening Foundation of Key Laboratory of Infrared Imaging Materials and Devices, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IIMDFJJ-21-11)”, “Shandong University Equipment Development Cultivation Project (zy202004)”, and “Shandong University Graduate Education Teaching Reform Research Project (XYJG2023129)”. The authors wish to express their appreciation to Yunxia Liu and Yakui Dong for their essential role in dataset development. In addition, Shandong University AI assistant (Qwen2.5-72B) provided language touch-ups and corrective editing during the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gangnian Zhao and Yingjian Liu designed the experiments, collected the data, organized the data, and wrote the paper; they contributed equally to this paper and should enjoy equal rights. Shuzhen Fan reviewed, edited and supervised the paper. Xian Zhao and Zhaojun Liu were responsible for the conceptualization of this work, including the construction of the framework underlying the dataset and the organization of related experiments. Yongfu Li was responsible for the methodology of this work. Four corresponding authors co- supervised the entire work. Junliang Liu, Cheng Fei, and Liqian Wang provided technical guidance on equipment, programming, and data analysis for the collection and construction of the dataset. Zhishuo Zhang was responsible for the collection and construction of a portion of the dataset. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed to its publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Zhao, G., Fan, S. et al. Tri-band vehicle and vessel dataset for artificial intelligence research. Sci Data 12, 592 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04945-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04945-6