Abstract

Suckermouth catfishes, with their evolved powerful features, have become notorious invasive species, causing significant damage to aquatic ecosystems. However, the lack of high-quality genomes severely restricts research on this group within the field. In this study, we de novo assembled the chromosome-level genome assembly of Pterygoplichthys pardalis using multiple platforms of sequencing data, including Illumina short reads, Nanopore long reads, and Hi-C sequencing reads, resulting in a 1.51 Gb genome assembly. Multiple evaluations, including read mapping ratio (98.52%), transcript mapping ratio (99.61%), conserved BUSCO gene set (98.8%), and N50 score (49.47 Mb), indicated the high continuity and accuracy of the genome assembly we generated. Genome annotation found that 0.97 Gb of genome sequences are repetitive sequences, accounting for 64.47% of the genome assembly. Further, 23,859 protein-coding genes were successfully predicted, 92.92% of which could be annotated in functional databases. This high-quality genome assembly of P. pardalis provides a valuable resource for understanding the genetic underpinnings of P. pardalis’s invasive success and offers critical data for future fisheries research and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

With their numerous evolved powerful features, suckermouth catfishes have emerged as one of the notorious invasive groups globally, with documented invasions across tropical and subtropical regions, including Southeast Asia, the southern United States, and Central America, exerting significant impacts on the ecosystem1,2,3,4. Notably, Pterygoplichthys pardalis, native to the Amazon Basin, serves as a famous and typical representative of such an invasive group5. It has established invasive populations various countries, where it disrupts food webs, alters benthic habitats through burrowing, and damages fisheries infrastructure2,3,6,7. More importantly, these invaders not only compete with native species over food resources, but they also aggressively prey on eggs and young fish, thereby leading to a decline in native fish populations and posing a significant threat to the integrity of the local ecological chain4,6. Economic costs arise from levee erosion, reduced catch yields, and expensive eradication efforts2,3,6,7, underscoring the urgency of understanding its biology to inform management strategies.

This omnivorous fish feeds on a wide variety of food sources, including algae, organic material, small invertebrates, and sediment particles1,8, enabling exploitation of resource-poor environments. Amazingly, significant changes in their gastric system, which functions as an additional respiratory organ, enable them to thrive in environments with low levels of dissolved oxygen9,10, which is the common feature of polluted or eutrophic habitats. Additionally, they possess the abilities to survive in cold temperatures and drought conditions by burrowing underground, even when the water level dips below the entrance of their burrows1,11. Its rapid growth, high reproductive capacity, and lack of natural predators have facilitated its accidental introduction into non-native habitats, where it rapidly establishes invasive populations1,12,13,14,15,16. These traits, coupled with a lack of natural predators in non-native ranges, enable P. pardalis to monopolize niches, displace native species, and degrade ecosystems12,13. Eventually, once these invaders establish a population, eradicating them becomes challenging. Despite scientists, including ichthyologists, ecologists, and evolutionary biologists, have been studying for decades1,7,14,17, genetic mechanisms underlying P. pardalis’s adaptability remain poorly understood. Only a single mitochondrial genome (NCBI Accession: NC_058365)18 and a very fragmented nuclear draft genome (contig N50: 4.15 kb)19 are insufficient for resolving these complex traits. More importantly, this situation significantly limits insights into molecular drivers of invasiveness and constrains comparative analyses with native and invasive relatives.

To address these challenges, we present a chromosome-level genome assembly (1.51 Gb) of P. pardalis by integrating Illumina short reads, Nanopore long reads, and Hi-C data. By combining multiple annotation strategies, we ultimately determined that 0.97 Gb of the genome are repetitive sequences, which account for 64.47% of the total genome, and we successfully predicted 23,859 protein-coding genes in the P. pardalis genome. These findings not only provide a high-quality genome resource for P. pardalis, but also facilitate large-scale comparative genomic studies and enable prevention- and control-oriented applications.

Methods

Data acquisition

The catfish samples used in this study were purchased from an ornamental fish wholesale market in Xi’an, China (Fig. 1). The remaining samples of this specimen (Catfish_01) have been cryopreserved at −80 °C in the Biodiversity Repository of the Institute of Basic and Translational Medicine at Xi’an Medical University. All animal specimens were collected legally in accordance with the policy of the Animal Care and Use Ethics of the institution. Genomic DNA was extracted from the muscle tissue of one suckermouth catfish (P. pardalis) using the Blood & Cell Culture DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To obtain a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly, data from multiple sequencing platforms were acquired: 1) A short-insert paired-end library was prepared and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform; 2) A Nanopore library was prepared and sequenced across 26 flow-cells using the Nanopore PromethION 48 (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, UK); 3) A Hi-C library was constructed and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform; 4) To support genome annotation, total RNAs was extracted from muscle using a TRIzol Kit (Life Technologies) and subsequently used for library construction and sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform. All library construction and genome/transcriptome sequencing processes were conducted in biotechnology companies according to their standard workflows. In total, we got 146.15 Gb of Illumina paired-end short-read data (Table 1), 218.07 Gb of Nanopore long-read sequencing data (Table 1), and 149.24 Gb of high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) sequencing data (Table 1).

Quality control of sequencing data

To facilitate high-quality genome assembly, we performed strict quality control processes. For Illumina reads, adaptor sequences and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) duplicates were removed from all paired-end reads with Perl scripts20. Additionally, any Illumina reads containing more than 5% unknown bases or exceeding 30 low-quality bases, along with their paired-end reads, were discarded21. For Nanopore reads, only reads with a mean quality score >7 were retained and used for subsequent analysis21.

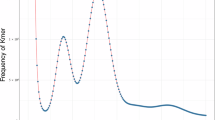

Genome size estimation

A k-mer based strategy was employed to estimate the genome size of P. pardalis. Using all the cleaned short-insert Illumina reads, a 17-mer was selected for this analysis (https://github.com/fanagislab/kmerfreq). The genome size can be calculated using the formula: G = Knum/Kdepth. G represents the estimated genome size, Knum denotes the total count of 17-mers, and Kdepth represents the peak depth of the 17-mers22. The genome of P. pardalis was estimated to be approximately 1.48 Gb, with a considerable level of heterozygosity (Fig. 2).

Genome assembly

The genome assembly was performed with the following steps: 1) Long reads from the Nanopore platform were used for the contig-level assembly using NextDenovo (v2.2; https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo). Key parameters were carefully set to ensure optimal assembly, including a read cutoff of 1k, a seed cutoff of 59754, and a blocksize of 5 g. 2) Cleaned short reads generated from the Illumina short-insert library were mapped onto the assembled contigs using BWA (v0.7.17)23. To further enhance the accuracy of the assembly at the single-base level, we performed two iterations of correction using Pilon (v1.22)24. 3) We mapped the Hi-C sequencing reads to the corrected contigs, and subsequently utilized Juicer (v1.5.7)25 and 3D de novo assembly (v180922)26 to perform chromosome-level genome assembly. Eventually, we successfully assembled the 1.51 Gb chromosome-level reference genome, with a total of 26 chromosomes and a scaffold N50 length of 49.47 Mb (Figs. 3, 4, Tables 2, 3). Notably, the assembled genome size closely aligned with the estimated size based on k-mer analysis (1.48 Gb) (Fig. 2), indicating the high-integrity of the genome assembly we acquired. To further evaluate the quality of the genome assembly, multiple strategies were employed, including the BUSCO (v5.2.2, Vertebrata_odb10)27 score (98.8%) (Table 4), the mapping ratio of short-insert reads (98.52%) (Table 5), transcripts (99.61%) (Tables 5, 6), Nanopore (99.89%) (Table 5), QV value (31.59), as well as the Hox clusters (Fig. 5). Among them, the Naopore reads were remapped with minimap2 (v2.26-r1175), and the QV scores were assessed by Merqury (v3.0.1; https://github.com/marbl/merqury). All these results indicate that the P. pardalis genome assembly exhibits both high integrity and accuracy.

Distributions of genomic elements in P. pardalis genome. Outer to inner ring are distributions of protein-coding genes, tandem repeats (TRP), long terminal repeats (LTR), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINE), long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE), DNA elements, and GC content, respectively.

Genome annotation

Tandem repetitive sequences within the genome were identified using Tandem Repeat Finder (v4.07)28. Non-interspersed repeats in the genome were annotated using RepeatMasker (v4.1.0)29. Transposable elements (TEs) in the genome were annotated at both the DNA and protein levels. A de novo repeat library at the DNA level was constructed using RepeatModeler (v1.0.4; GitHub - Dfam-consortium/RepeatModeler: De-Novo Repeat Discovery Tool) enabling the identification of potential novel repetitive sequences. The genome assembly was searched against Repbase (v23.06) using RepeatMasker (v4.1.0)29 to detect homologous repetitive sequences, providing a more comprehensive picture of the repetitive sequence content. RM-BLASTX within RepeatProteinMask (v4.1.0) was employed to query the TE protein database at the protein level. We found that 0.97 Gb of the genome length consisted of repetitive sequences, which accounts for 64.47% of the genome assembly of P. pardalis (Table 7). Among them, DNA elements (499.77 Mb; 33.15%) constitute the largest proportion of transposable elements (TEs; Table 8), which were followed by the long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs; 144.01 Mb; 9.55%), long terminal repeats (LTRs; 78.00 Mb; 5.17%), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs; 29.27 Mb; 1.94%), in the P. pardalis genome (Table 8).

Prediction and functional annotation of protein-coding genes

Protein-coding genes were predicted based on three distinct strategies. For de novo-based prediction, the transcripts of P. pardalis muscle tissue were assembled based on RNA-seq data using Bridger (r2014-12-01)30. Subsequently, the assembled transcripts were filtered and underwent primary prediction using the PASA pipeline (v2.1.0)31 and AUGUSTUS (v2.5.5)32. Protein sequences, including Bagarius yarrelli (GCA_005784505.1), Ameiurus melas (GCA_012411365.1), Ictalurus punctatus (GCF_001660625.1), Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (GCF_009078355.1), Tachysurus fulvidraco(GCF_003724035.1), Hemibagrus wyckioides (GCA_019097595.1), Silurus meridionalis (GCF_014805685.1), Clarias magur (GCA_013621035.1), Danio rerio (GCF_000002035.6), Pelteobagrus fulvidraco (http://gigadb.org/dataset/100506), and Glyptosternon maculatum (https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giy104), were downloaded for homology-based prediction. To further refine the coding gene prediction, we selected the longest transcript for each gene and removed those with premature termination sites. Using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (v2.2.26; https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/blast+/2.2.26/) with an e-value threshold of 1e-5, we then performed homology-based annotation using GeneWise (v2.4.1)33. For transcript-based prediction, RNA-seq reads were mapped to the assembled genome using BLAT (v34)34 and spliced alignments were subsequently linked using the PASA pipeline (v2.1.0)31. Finally, the predicted coding genes obtained from the three strategies were integrated using EvidenceModeler (r2012-06-25)35. We successfully predicted 23,859 protein-coding genes in the P. pardalis genome (Table 9), with the BUSCO score of 87.7% (metazoa_odb10, Table 10). To validate the quality of these predicted protein-coding genes, we conducted a comparative analysis of length distributions across many gene structures, including mRNA (Fig. 6a), coding sequences (CDS) (Fig. 6b), exons (Fig. 6c), and introns (Fig. 6d), between P. pardalis and other species. Our results indicated that the predicted protein-coding genes in P. pardalis exhibited comparable quality to those previously reported in other species (Fig. 6).

For functional annotation, all the predicted protein-coding genes were aligned to multiple databases, including InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/), Gene Ontology (GO) (https://geneontology.org/), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.kegg.jp/), UniProt/SwissProt (https://www.uniprot.org/), UniProt/TrEMBL (https://www.uniprot.org/), and the Non-Redundant Protein Sequence Database (NR; https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db). We found the majority of the predicted genes (22,169; 92.92%) had homologous genes in various public databases (Table 9).

Data Records

All the raw sequencing data, including Nanopore and Illumina reads, have been uploaded to the NCBI database (National Center for Biotechnology Information, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA116548336. The genome assembly and annotation files were uploaded to the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.bk3j9kdgh)37 and Genbank dataset (GCA_050231285.1)38.

Technical Validation

The final assembly (1.51 Gb) of P. pardalis is slightly larger than the estimated genome size (1.48 Gb), which may be cause by the genome heterozygosity (Fig. 2). Three distinct strategies were employed to predict protein-coding genes. Using Hi-C technology, we successfully assembled 26 chromosomes of P. pardalis (Fig. 3), which is consistent with the result of a karyotype experiment in a previous study39. Genome annotation further revealed that the length and proportion of repetitive sequences in P. pardalis (0.97 Gb and 64.47%) are obviously higher than those of other catfish species (I. punctatus: 0.27 Gb and 34.92%, P. hypophthalmus: 0.27 Gb and 36.90%, H. wyckioides: 0.32 Gb and 40.12%, S. meridionalis: 0.30 Gb and 40.12%, G. maculatum: 0.25 Gb and 32.76%, and P. fulvidraco: 0.28 Gb and 38.47%) (Fig. 4), indicating that the expansion of repetitive regions is the main reason for the large genome of P. pardalis.

Code availability

No specific code or script was used in this study. All data processing commands were executed according to the official manuals and standard protocols of the respective software. The Methods section includes the software versions, URLs, and parameters.

References

Hoover, J. J., Killgore, K. J. & Cofrancesco, A. F. Suckermouth catfishes: threats to aquatic ecosystems of the united states? Aquatic Nuisance Species Res Prog Bull 04–1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.04.018 (2004).

Hossain, M. Y., Vadas, R. L., Ruiz-Carus, R. & Galib, S. M. Amazon Sailfin Catfish Pterygoplichthys pardalis (Loricariidae) in Bangladesh: A Critical Review of Its Invasive Threat to Native and Endemic Aquatic Species. Fishes 3, 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes3010014 (2018).

Orfinger, A. B. & Goodding, D. D. The global invasion of the suckermouth armored catfish genus pterygoplichthys (siluriformes: loricariidae): annotated list of species, distributional summary, and assessment of impacts. Zoological Studies 57, https://doi.org/10.6620/ZS.2018.57-07 (2018).

Quintana, Y., Keppeler, F. W. & Winemiller, K. O. Does invasion by armored catfish shift trophic ecology of native fishes? Evidence from stable isotope analysis. Ecology 104, e4024, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.4024 (2023).

Schoch, C. L. et al. NCBI Taxonomy: a comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database (Oxford), baaa062, https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baaa062 (2020).

Mohammad, H., Robert, V., Ramon, R. C. & Galib, S. M. Amazon sailfin catfish pterygoplichthys pardalis (loricariidae) in bangladesh: a critical review of its invasive threat to native and endemic aquatic species. Fishes 3, 14-, https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes3010014 (2018).

Anguebes, F., Bassam, A., Abatal, M., Tzuc, O. M. & Pedro, L. S. Physical and chemical properties of biodiesel obtained from amazon sailfin catfish (pterygoplichthys pardalis) biomass oil. Journal of Chemistry 2019, 7829630, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7829630 (2019).

Delariva, R. L. & Agostinho, A. A. Relationship between morphology and diets of six neotropical loricariids. Journal of Fish Biology 58, 832–847, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2001.tb00534.x (2010).

Armbruster, J. Modification of digestive tract for holding air in Loricariidae in Scloloplacid catfishes. Copeia 3, 663–675, https://doi.org/10.2307/1447796 (1998).

Hussan, A., Choudhury, T. G., Das, A. & Gita, S. Suckermouth sailfin catfishes: A future threat to aquatic ecosystems of India. Aquaculture times 2, 20–22 (2016).

Nico, L. G. & Martin, N. T. The south american suckermouth armored catfish, pterygoplichthys anisitsi (pisces: loricaridae), in texas, with comments on foreign fish introductions in the american southwest. Southwestern Naturalist 46, 98–104, https://doi.org/10.2307/3672381 (2001).

Ebenstein, D., Calderon, C., Troncoso, O. P. & Torres, F. G. Characterization of dermal plates from armored catfish pterygoplichthys pardalis reveals sandwich-like nanocomposite structure. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 45, 175–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.02.002 (2015).

Gibbs, M. A., Kurth, B. N. & Bridges, C. D. Age and growth of the loricariid catfish Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus in Volusia Blue Spring, Florida. Aquatic Invasions 8, https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2013.8.2.08 (2013).

Krishnakumar, K. et al. When pets become pests–exotic aquarium fishes and biological invasions in Kerala, India. Current science 97, 474–476 (2009).

Nurubhasha, R. et al. Extraction and characterization of collagen from the skin of Pterygoplichthys pardalis and its potential application in food industries. Food science and biotechnology 28, 1811–1817, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-019-00601-z (2019).

Raj, S., Devi, S. S., Joy, A. & Kumar, A. B. On the reproductive biology of the invasive Armoured Sailfin Catfish Pterygoplicthys pardalis (Castelnau, 1855) (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the natural drainages in Thiruvananthapuram, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 13, 19263–19273, https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.7164.13.9.19263-19273 (2021).

Chaichana, R. & Jongphadungkiet, S. Assessment of the invasive catfish pterygoplichthys pardalis (castelnau, 1855) in thailand: ecological impacts and biological control alternatives. Tropical Zoology 25, 173–182, https://doi.org/10.1080/03946975.2012.738494 (2012).

Xia, W. X. et al. Next-generation sequencing yields the complete mitochondrial genome of Pterygoplichthys pardalis (Loricariidae; Siluriformes). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour 6, 3209–3211, https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2021.1959447 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. The channel catfish genome sequence provides insights into the evolution of scale formation in teleosts. Nature communications 7, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11757 (2016).

Chen, L. et al. Large-scale ruminant genome sequencing provides insights into their evolution and distinct traits. Science 364 (6446), https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav6202 (2019).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and fexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol 16, 259, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0831-x (2015).

Liu, B. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. Genomics, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4005(96)02015-1 (2013).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS one 9, e112963, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell systems 3, 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3327 (2017).

Simao, F. A. et al. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic acids research 27, 573–580, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999).

Bedell, J. A., Korf, I. & Gish, W. MaskerAid: a performance enhancement to RepeatMasker. Bioinformatics 16, 1040–1041, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1040 (2000).

Chang, Z. et al. Bridger: a new framework for de novo transcriptome assembly using RNA-seq data. Genome biology 16, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0596-2 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 5654–5666, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003).

Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19, 215–225, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080 (2003).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res 14, 988–95, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1865504 (2004).

Kent, W. J. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res 12, 656–64, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.229202 (2002).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EvidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome biology 9, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP539024 (2024).

Xia, W. X. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Pterygoplichthys pardalis. Dryad. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.bk3j9kdgh (2022).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_050231285.1 (2025).

Da Silva, F. A. et al. Transposable DNA Elements in Amazonian Fish: From Genome Enlargement to Genetic Adaptation to Stressful Environments. Cytogenet Genome Res 160, 148–155, https://doi.org/10.1159/000507104 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Fund of Shaanxi Provincial Education Department (21JK0888), Innovation Team Foundation of Xi’an Medical University (2021TD05), Young Talent Fund of Association for Science and Technology in Shaanxi, China (20240209). We thank Christine Watts for help in honing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X. and Y.Z. supervised the project. W.X. collected the samples. W.X. and Y.L. performed the sequencing of PacBio, Illumina, and Hi-C data. W.X., H.X., Y.L. and H.J. performed the genome assemble and annotation analysis. W.X. prepared all graphical illustrations. W.X. wrote the manuscript. L.X., H.X., Y.W., Y.Y., X.L. and W.F. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, W., Xu, H., Liu, Y. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Pterygoplichthys pardalis. Sci Data 12, 1091 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05273-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05273-5