Abstract

Accurate and continuous monitoring of soil moisture (SM) is crucial for a wide range of applications in agriculture, hydrology, and climate modelling. In this study, we present a novel machine learning (ML) based framework for generating a continuously updated, multilayer global SM dataset: SMRFR (Soil Moisture via Random Forest Regression). Leveraging publicly available reanalysis and remote sensing data, SMRFR provides daily SM estimates at five soil layers (0–5, 5–10, 10–30, 30–50 and 50–100 cm) with a spatial resolution of 9 km, covering the period from 2000 to 2023. Evaluation results demonstrate that SMRFR effectively captures both spatial and temporal SM variability. It also exhibits strong generalization capacity, successfully transferring knowledge across continents and accurately capturing transient and seasonal SM dynamics following rainfall events. SMRFR achieved an unbiased root mean square error of 0.0339 m3/m3 on the validation set. Our novel SM dataset offers a basis and valuable reference for agricultural, hydrological, and ecological research, enabling improved analysis and modelling of SM dynamics at regional to global scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Soil moisture (SM) is a critical component of the global hydrological cycle and a key climate variable influencing water, carbon, and energy fluxes at the land-atmosphere interface1,2,3,4,5. It influences hydrological processes such as runoff, infiltration, and evapotranspiration, with broad applications in weather forecasting4,6, drought monitoring7,8,9,10, flood prediction, and agricultural management11. SM is typically divided into surface soil moisture (SSM) and root zone soil moisture (RZSM), while RZSM being particularly critical as it regulates plant transpiration, nutrient uptake12, and drought resilience, and plays a vital role in climate feedbacks, groundwater recharge13, and ecosystem stability14. Accurate and continuous SM estimation, especially at across soil depths, is essential for understanding terrestrial water dynamics and mitigating climate-related risks.

Despite its significance, obtaining high-quality SM data with adequate spatial and temporal resolution remains a challenge15,16. In-situ networks17,18,19,20 offering high accuracy SM observations and vertical profile insights but are limited by sparse spatial coverage due to logistical and financial constraints. Satellite-based missions (e.g. SMOS21, SMAP22) enable global coverage but are restricted to the top ~5 cm of soil23 and often perform poorly in densely vegetated24,25, topographically complex26, frozen27, or snow-covered28,29 environments, resulting in data gaps. Alternatively, physics-based models such as Land Surface Models (LSMs) and Earth System Models (ESMs)30,31,32 provide multilayer SM estimates, but rely on parameterizations that introduce uncertainties due to incomplete physical representations and meteorological forcing errors2,33,34, especially for RZSM35.

Machine learning (ML) approaches have recently emerged as powerful alternatives, enabling data-driven SM estimation by leveraging large-scale environmental data. Several studies have pioneered the application of ML to estimate SM, especially for RZSM, and introduced a number of datasets36,37,38,39,40,41, NNsm37 provides SSM with 36-km resolution at a global scale (daily, 2002–2019) using Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), SoMo.ml38 offers global SM at three soil layers (0–10, 10–30 and 30–50 cm) with 0.25° spatial resolution (daily, 2000–2019) based on Long Short-Term Memory neural network (LSTM), SoMo.ml-EU40 with 0.1° resolution over Europe as an advancement of Somo.ml, and SMCI41 delivers multilayer SM (0–100 cm) at 1-km resolution over China using Random Forest42 (RF). However, these ML-based datasets are often restricted by coarse spatial resolution, lack of multi-depth information, or limited validation across climatic regimes.

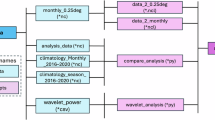

To address these limitations, we introduce SMRFR (Soil Moisture via Random Forest Regression), a long-term, global, daily, multilayer SM dataset generated using a novel ML-based framework (Fig. 1). Our approach combines quality-controlled in-situ SM data from International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN20) and multi-source predictors from ERA5-Land reanalysis32 and remote sensing products (e.g., MODIS vegetation indices, soil properties, and topographic features). To ensure robust learning and generalizability, we employed optimized RF models and applied Extended Triple Collocation43 (ETC) method to select high quality stations for training.

SMRFR provides globally consistent daily SM estimates at five depth layers (0–5, 5–10, 10–30, 30–50, and 50–100 cm), from 2000 to 2023, with a spatial resolution of 9 km (see Table 1). Compared to existing satellite-based or model-derived products, SMRFR overcomes key limitations by: (i) offering multilayer SM profiles beyond surface-only estimates, (ii) improving spatial resolution than typical ML datasets, (iii) utilizing strict data quality control and harmonized multi-source inputs, and (iv) enabling potential transferability to finer resolutions (e.g., 1 km) and regional applications. SMRFR bridges gaps between existing methods and datasets, providing a scientific foundation for improved SM modelling, climate impact research, and water resource management.

Methods

In-situ SM observations

In-situ SM data measured by ISMN stations was obtained as target SM data, all the SM time series were resampled to a daily temporal resolution to synchronize differences across sensors. Following established quality control guidelines44, measurements flagged as unreliable were removed. In addition, sensors with insufficiently documented data (e.g., fewer than 200 days of records) were excluded to accommodate interannual SM variability while ensuring enough effective stations.

Another in-situ SM dataset45 was obtained from the National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (CEMADEM) of Brazil for evaluating the capability of SMRFR in transferring knowledge of SM dynamic across regions (e.g., across-continents)46, whose spatial representativity has been proved47. Outliers were removed and data completeness was checked to ensure dataset integrity for evaluation purposes.

Predictors for SM modelling

The predictors employed in RF models (see Table 2) were carefully selected based on their strong relevance to SM dynamics. The dynamic data component was primarily obtained from the ERA5-Land32, the application of ERA5-Land effectively circumvents the challenges associated with spatial scale48 and time coverage38 inconsistencies of multiple remote sensing observations. Furthermore, the timely updates of ERA5-Land facilitate the continuous generation of SMRFR, its fine spatial (9-km) and temporal (hourly) resolutions make it particularly suitable for capturing short- and long-term soil water dynamics. Recognizing that SM dynamics are intricately intertwined with meteorological factors, yet ultimately manifest in SM itself, we incorporated SM as a predictive variable. This approach encapsulates the information typically reflected by a multitude of meteorological predictors, thereby reducing the reliance on auxiliary data through a form of data assimilation. MODIS vegetation indices (e.g., Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, NDVI, Enhanced Vegetation Index, EVI) were included to capture vegetation’s role in SM retention and evapotranspiration. Vegetation mediates the exchange of water between the land and atmosphere, thus playing an essential role in both retaining and depleting soil water.

Variations in topography, altitude, and vegetation cover affect solar radiation and hydrological processes like runoff. Additionally, soil heterogeneity, including differences in structure, composition38, and water retention capacity, influences the horizontal distribution and vertical movement of SM49,50,51,52,53,54. Thus, static predictors (e.g. topography, soil texture, bulk density, and field capacity) were incorporated to account for the effects of terrain and soil hydraulic properties on water infiltration and retention.

To ensure consistency across diverse input sources, all predictors were pre-processed to match the SMRFR grid (9 km, daily). ERA5-Land variables were averaged to daily means, and Vegetation indices were linearly interpolated to daily frequency. Soil properties data (e.g., sand, clay, bulk density) were aggregated from 250 m to 9 km using spatial means. All predictors were then mapped to target soil depths, projected, and clipped to a unified global land mask.

Model training and application

ML performance improves with the accuracy of input data55,56, while ETC approach57,58 has been validated as an effective tool for enhancing estimation accuracy by controlling the quality of the training data59,60,61. It is based on assumptions of (i) orthogonality of product errors, (ii) independence among the errors of the three datasets, and iii) errors in the products that are linearly related to the reference dataset. In this study, we applied the ETC method to evaluate the consistency among three independent sources: in-situ observations, land surface model outputs, and remote sensing products (see Table S1 in Supplementary Information document) and the assumed “truth”. Based on the coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.762), we selected high-quality stations for training. A total of 433 stations were retained as the final representative subset (Fig. 2). This selective strategy ensures that both model training and validation are grounded in the most reliable and representative SM data available.

We initially evaluated multiple ML algorithms, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN). Among them, the RF algorithm showed the best overall performance in terms of root mean square error (RMSE) and correlation coefficient (see Table S2), particularly in geographically heterogeneous regions. The quality and representativeness of the training data are critical to model performance63. Therefore, we restricted the training set to a subset of carefully selected stations. Furthermore, estimated SM derived from the overlying layers were incorporated as input variables to enhance the predictive capabilities for deeper soil layers, a strategy previously validated38. A five-fold cross-validation grid search was conducted to optimize RF hyperparameters, identifying the configuration that maximized model accuracy. For each soil layer, the model was trained and validated on the corresponding curated dataset to ensure robustness and representativeness. The final major hyperparameter settings used were n_estimator = 1100, max_depth = 560.

Importance of predictors

The contributions of predictors in SM modelling were assessed using the Mean Decrease in Accuracy (MDA) metric, which quantifies the decline in model performance when a predictor’s values are randomly permuted. To facilitate a systematic evaluation, we categorized predictors into groups based on their type: static attributes (e.g., topography, soil properties), vegetation indices (VI) (e.g., NDVI & EVI).

As depicted in Fig. 3, the dominant role of SM from upper layers in predicting deeper-layer SM highlights the importance of vertical water transfer and moisture memory effects, especially in lower layers where atmospheric influence is reduced. This vertical dependency enables the model to capture the lagged infiltration processes and persistent storage effects that are key to RZSM dynamics.

Among non-SM predictors, soil properties (e.g., clay and sand content, field capacity) exert more influence on spatial variability than on temporal fluctuations64. These features govern the infiltration rate, water retention capacity, and hydraulic conductivity of soils65,66, especially under contrasting soil types (e.g., sandy vs. clayey regions). In regions with limited vegetation or low rainfall variability, these soil properties can dominate SM behavior. VI also play a crucial role in surface and near-surface layers, as they influence SM through both direct mechanisms (e.g., interception, transpiration, root water uptake) and indirect effects (e.g., seasonal phenology, surface energy balance regulation), all of which strongly short-term SM dynamics67,68. Their contribution to model accuracy decreases with depth, which is consistent with the diminishing role of vegetation processes below the rooting zone. In contrast, soil temperature exhibited marginal contribution, likely because their influence is already implicitly captured through other variables like SM and VI.

Data Records

The SMRFR dataset can be accessed at figshare69. The compressed files (.zip) contain data in zarr format for the five respective layers. An example file name is “SMRFR_ < YYYY > _v1.0.zarr”, with YYYY standing for year.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the suitability and potential of ML-based models for estimating SM data, concentrating on three key aspects. First, we examined the modelling performance during the training phase. Second, we evaluated the temporal dynamics and spatial patterns of SMRFR. Finally, we assessed the capability of SMRFR in knowledge transfer scenarios. The ability of these models to transfer knowledge across regions is vital for producing enhanced quality data in domains where observations are scarce.

Evaluation on SMRFR and its modelling

Validation of SM Modelling

As shown in Fig. 4a, SM estimates exhibit a strong correlation with in-situ measurements. Model performance improves with increasing soil depth, as indicated by higher correlation coefficients (ranging from 0.947 to 0.982) and lower unbiased RMSE (ubRMSE, decreasing from 0.035 to 0.022 m³/m³). This trend likely reflects the greater temporal stability of deeper soil layers, which are less affected by short-term meteorological variations and surface interactions, leading to more predictable moisture patterns and reduced model uncertainty. The frequency distributions in Fig. 4b further demonstrate this consistency, showing close alignment between estimated and observed SM values. A slight overestimation is observed around medium SM levels (0.2–0.4 m³/m³), which may be influenced by regional variations in soil hydraulic properties and vegetation cover. Figure 4c highlights the model’s robustness under diverse climatic conditions, with estimated SM values closely matching in-situ data across both arid and humid regions.

To further assess model robustness under diverse climate regimes, we evaluated SMRFR performance across five Köppen-Geiger climate70 zones using validation stations withheld from model training (see Fig. 5 and Fig. S1). The results show that the model performs best in temperate and continental climates, with the highest correlations and lowest errors. Tropical and polar regions performed slightly worse in comparison, with higher variability and errors, which may be due to complex vegetation dynamics, snow-related processes and fewer ground truth data.

Evaluation of SMRFR SSM (0–5 cm) performance across five Köppen-Geiger climate types using validation stations excluded from model training. (a) Correlation coefficient, (b) Bias, (c) ubRMSE, and (d) MAE are shown as violin plots overlaid with boxplots. Sample size is indicated above the plots in (a).

These climate-based differences highlight both the generalizability and limits of SMRFR and emphasize the importance of region-specific evaluation in global-scale modelling. Benefiting from extensive data collection and rigorous quality control, our training data can encompass a wide spectrum of various climatic conditions, enabling strong generalization even in complex hydrological environments. In summary, the ML models effectively capture SM dynamics and can accurately estimate SM at unseen locations.

Temporal dynamics of SMRFR

We compared in-situ SM, estimated SM, and local precipitation to investigate the temporal dynamics of SMRFR at stations (see Fig. 6 and Figs. S2–4). The dynamics of SMRFR aligned closely with in-situ SM, particularly in upper soil layers, with well-aligned scatters patterns. During the dry season with minimal precipitation, both SMRFR and in-situ SM showed low, stable moisture levels, suggesting that the model effectively captures seasonal depletion and is sensitive to rainfall dynamics.

A wet bias was observed in SMRFR compared to in-situ SM, intensifying with soil depth and dry season progression. This may stem from the high hydraulic conductivity71 of local soil (e.g., sandy clay loam at station Yosemite-Village-12-W), characterized by large pore spaces, having high infiltration rates but low water retention capacity, leading to fast dry-down in the dry season. This highlights a shortcoming of ML models, which has limited ability to learn soil-specific hydraulic properties.

Following a prolonged dry period, a moderate rainfall in early September triggered rapid wetting in shallow layers, while deeper layers (>30 cm) remained unaffected. This reflects increased water absorption capacity in desiccated soils. In contrast, during the wet season, elevated SM levels allowed infiltration to reach deeper layers (e.g., 50–100 cm, as seen in April). These examples highlight the model’s ability to empirically capture physically plausible moisture dynamics through data-driven learning.

However, SMRFR showed a muted response to intense rainfall compared to in-situ SM, likely due to the inherent averaging effect of RF outputs, which reflect the arithmetic mean of numerous decision trees, leading to a consensus result devoid of extreme values. While this reduces variance and noise, it limits model’s capability to replicate sharp infiltration and runoff responses. A hybrid ML-Physical modelling approach (e.g., integrate with hydrological models) might enhance the physical realism of SM dynamics, especially for infiltration and runoff processes during extreme rainfall events.

Spatial patterns of SMRFR

We further assessed the spatial patterns of SMRFR and its response to extreme events. For illustration, we analysed the localized multi-layer SM maps before and after an extreme rainfall event (details in Fig. 7a). SMRFR provides a comprehensive depiction of SM characteristics within this region, featuring high SM levels in coastal monsoon regions (e.g., the Indian Peninsula and southern China) and drier conditions in interior arid zones. Wet-up patterns correspond to precipitation levels and align with the extreme rainfall event72. During this event, the localized total precipitation exceeding 700 mm in the Indian Peninsula, south-central China, and the Himalayan region, leading to significant SM increases. SMRFR effectively captures both the spatial continuity and localized variability of SM changes.

Within the Central and Southern Peninsula, SM profiles vary notably with depth, where northern regions exhibiting lower SM levels in deeper layers. This likely reflects vertical heterogeneity in soil texture and land cover, influenced by elevation gradients. For example, plains dominated by crops may have shallower rooting depths compared to northern forested areas, affecting vertical SM redistribution73.

Difference maps (Fig. 7n-r) highlight significant wet-up in surface layers following the event, while deeper horizons show more limited responses. This attenuation may result from combined effects of rainfall interception, inherent evaporation, and lateral movement of SM. Notably, along the Himalayas region, despite intense rainfall, minimal SM increase were observed. This suggests that little to no rainfall infiltrated into the soil to wet it further, it could be influenced by near-saturated or saturated soil, which promote runoff, or frozen/snow-covered soils, which inhibit infiltration.

To further evaluate the spatial representativeness of SMRFR, we conducted an in-depth regional analysis across three geographically and climatically distinct areas: the Loess Plateau (China, temperate semi-arid), the Cerrado (Brazil, tropical savanna), and the Central Great Plains (USA, temperate continental), as illustrated in Fig. 8. These regions encompass a wide range of terrain complexity, land cover types, and soil properties, offering a representative testbed for evaluating the SMRFR’s ability to capture localized SM variability.

Evaluation of SMRFR and environmental conditions in three regions: (a) Loess Plateau (China), (b) Cerrado (Brazil), and (c) Central Great Plains (USA). Columns include: (1) SMRFR annual mean SM (2020), (2) CCI annual mean SM (2020), (3) correlation with CCI, (4) RMSE, (5) elevation (DEM), (6) annual mean NDVI (2020), (7) Clay fraction, and (8) Köppen-Geiger climate classification.

In the Central Great Plains, SMRFR closely follows terrain-induced SM gradients, with higher moisture observed in lowland areas and declining levels toward elevated zones. These spatial variations are consistent with local patterns in clay content and vegetation density, reinforcing SMRFR’s sensitivity to surface and subsurface hydrological controls. In contrast, SMRFR performance deteriorates in more topographically heterogeneous environments, such as the southern Loess Plateau and the southern Cerrado Plateau, where rapid changes in elevation and sparse vegetation cover introduce higher uncertainty. This is reflected in both reduced correlation and elevated RMSE. These examples collectively demonstrate SMRFR’s strengths in relatively homogeneous landscapes and highlight areas where further refinement or targeted calibration could improve accuracy in complex terrains.

Comparison with global SM datasets

In this section, we examined the spatial patterns of SMRFR and existing datasets at global scale. The long term global SSM and RZSM states over the entire period (2000–2023) are presented in Fig. 9 and Fig. S5. Overall, SMRFR exhibits spatial distributions consistent with reference datasets, capturing expected SM gradients driven by topography and climate, characterized by (i) wetter conditions in tropical and monsoon regions, and (ii) drier conditions in inland and highland regions.

Comparison of SMRFR with long term SSM means from ERA5 land, GLEAM, and ESA-CCI. Along the diagonal are individual dataset maps, above the diagonal are difference maps (row minus column) and below the diagonal are frequency distributions comparisons. Only grid cells where all datasets are available are used.

Notably, SMRFR unveils distinctive regional traits, especially in RZSM maps, where higher SM levels are observed in some arid regions (e.g., the Sahara Desert and the Middle East) compared to other datasets. These disparities may originate from multiple factors, including differences in input data, processing methodologies and fundamental distinctions in the operational mechanisms between ML and LSMs in simulating SM dynamics. This highlights the necessity for intensive evaluation and inter-comparison studies to better comprehend the underlying causes of these variations. The differences between frequency distributions may reflect the ML algorithm’s heightened sensitivity to distinct features embedded within the training data. Continued efforts are needed to enhance the accuracy and robustness of SM estimations.

Capability of ML models to transfer knowledge across continents

In regions with limited or no in-situ observations, SM data are generated by learning SM mechanisms from other locations. Therefore, it’s essential to validate capability of SMRFR to transfer knowledge across regions (e.g., across continents).

To this end, the independent SM dataset45 was employed as a reference, along with other SM products. Notably, none of stations from this dataset was involved in SM modelling. Additionally, none of representative stations were distributed in eastern Brazil (see Fig. 2), where the stations of this dataset located in. Thus, SMRFR estimates in this region rely purely on knowledge learned from external training data. We focus on: (i) the responsiveness of SMRFR to local SM dynamics and rainfall events and (ii) consistency and differences between SMRFR and other datasets.

As depicted in Fig. 10, all the time series exhibit strong consistency in temporal SM dynamics, with SM peaks occurring along with heavy rainfall in rainy season while lower SM levels in dry periods. The nearly consistent dynamic fluctuation of SMRFR in tandem with in-situ SM showcases the heightened sensitivity of SMRFR to minute SM variations, highlighting its capability to simulate both seasonal and interannual SM variability. Despite this, varying degrees of wet bias are observed across all four products compared to in-situ SM, suggesting the overestimations in such semi-arid regions. Notably, SMRFR performs best in this transfer-learning scenario, with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.0331 m³/m³, outperforming ERA5-Land (0.1286), ESA CCI (0.1091), and GLEAM (0.1681).

Station-level evaluation (Fig. 11) further confirms SMRFR’s superior accuracy, showing the lowest bias, ubRMSE and MAE of 0.0273 m³/m³, 0.0339 m³/m³, 0.0439 m³/m³ and acceptable correlation coefficient of 0.65. The distributions of MAE and correlation coefficients reveal that while the relative temporal dynamics of SM are well-captured in these datasets, accurate estimation of SM values remains a challenge, particularly for LSM-based datasets74,75.

In summary, SMRFR demonstrates three key advantages: (i) strong ability to capture temporal SM dynamics and seasonal patterns, (ii) responsiveness to both short- and long-term rainfall variations and (iii) reliable estimation of absolute SM levels. These strengths reflect ML model’s robust learning capacity and its potential to support knowledge transfer across diverse regions.

However, it is worth noting that the current validation is grounded on semi-arid regions. Whether the ML-model can maintain its superior performance under disparate climatic conditions (e.g., extreme drought, high humidity, or more complex scenarios) remains uncertain. Future investigations should extend evaluation to broader environmental contexts to further enhance model robustness and generalizability.

Usage Notes

Despite the significant enhancement in accessibility of global SM datasets, there persist limitations, for instance, coarse spatial resolutions (25–50 km)22,38,76,77, simplified vertical structures (e.g., single root zone layer)78 and uneven continental coverage36,39,40. These limit the consideration of land surface heterogeneity and large-scale analysis of climate-SM interactions. To satisfy the increasing requirement for high resolution SM data16,79, this study introduces an innovative framework that harnesses the prowess of ML to systematically generate comprehensive, global-scale, multilayer SM datasets, using multi-source data. As a pilot step, we generated SMRFR, a novel SM dataset which provides global daily SM estimates at five soil layers (0–100 cm) at 9-km resolution from 2000 to 2023, with planned enhancement to 1-km resolution.

During training and validation, the ML framework demonstrated remarkable proficiency in deciphering intricate, nonlinear relationships and dynamic interactions between SM and environmental drivers. Consistent with earlier findings38, SM itself emerged as the dominant factor in determining the model inputs, suggesting that the framework can be streamlined to reduce data dependency. SMRFR also can exhibits strong transferability, particularly in semi-arid regions, where it effectively captures seasonal and event-scale SM fluctuations in the absence of local training data.

As earth observation data expand, ML continues to gain traction in earth system modelling, including SM, solar radiation80 and precipitation81. However, representing global SM dynamics with a single model per soil layer remains challenging, given the diversity in soil properties, topography, surface roughness, vegetation cover, and freeze-thaw dynamics. These complexities can lead to region-specific performance variations56. Future improvements may benefit from regional model specialization or clustering approaches39. In addition, while SMRFR is suitable for large-scale and regional studies, current resolution may be insufficient for field-scale applications. Finer-resolution SM datasets (e.g. hundred-meter scale or small) are needed to support precision agriculture and irrigation planning16,82.

SMRFR supports a range of applications across agriculture, hydrology, and ecology. It can enhance hydrological models (e.g., SWAT, VIC) by providing high-resolution, multilayer SM inputs that improve simulations of runoff, infiltration, and evapotranspiration processes. For instance, surface layers (e.g., 0–30 cm) support plant-available water estimation in SWAT, while the deeper profiles (up to 100 cm) enhance root-zone moisture representation in VIC. SMRFR can also complements satellite-based SM products for gap-filling and bias correction, and may be integrated with climate datasets (e.g., CMIP6) to assess long-term SM trends and their climate impacts. Regional biases can be further corrected using in-situ networks (e.g., COSMOS, FLUXNET. By facilitating seamless integration, calibration, and validation, SMRFR can enable large-scale SM analysis and provide new opportunities for drought monitoring, water resource management83, and ecosystem research.

Code availability

The RF models of this study and figure scripts are available from https://github.com/trust44/SciData2024_SMRFR_v1.

References

Gruber, A. et al. Estimating error cross-correlations in soil moisture data sets using extended collocation analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 121, 1208–1219 (2016).

Kumar, S. V., Reichle, R. H., Koster, R. D., Crow, W. T. & Peters-Lidard, C. D. Role of Subsurface Physics in the Assimilation of Surface Soil Moisture Observations. J. Hydrometeorol. 10, 1534–1547 (2009).

Humphrey, V. et al. Soil moisture–atmosphere feedback dominates land carbon uptake variability. Nature 592, 65–69 (2021).

Entekhabi, D., Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. & Castelli, F. Mutual interaction of soil moisture state and atmospheric processes. J. Hydrol. 184, 3–17 (1996).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 99, 125–161 (2010).

Dirmeyer, P. A. & Halder, S. Sensitivity of Numerical Weather Forecasts to Initial Soil Moisture Variations in CFSv2. WEATHER Forecast. 31 (2016).

Velpuri, N. M., Senay, G. B. & Morisette, J. T. Evaluating New SMAP Soil Moisture for Drought Monitoring in the Rangelands of the US High Plains. Rangelands 38, 183–190 (2016).

Mishra, A., Vu, T., Veettil, A. V. & Entekhabi, D. Drought monitoring with soil moisture active passive (SMAP) measurements. J. Hydrol. 552, 620–632 (2017).

Chawla, I., Karthikeyan, L. & Mishra, A. K. A review of remote sensing applications for water security: Quantity, quality, and extremes. J. Hydrol. 585, 124826 (2020).

Tijdeman, E. & Menzel, L. The development and persistence of soil moisture stress during drought across southwestern Germany. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 2009–2025 (2021).

Ma, Y. A root zone model for estimating soil water balance and crop yield responses to deficit irrigation in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. (2013).

Wang, J., Niu, W., Zhang, M. & Li, Y. Effect of alternate partial root-zone drip irrigation on soil bacterial communities and tomato yield. Appl. Soil Ecol. 119, 250–259 (2017).

Dash, Ch. J., Sarangi, A., Singh, D. K. & Adhikary, P. P. Numerical simulation to assess potential groundwater recharge and net groundwater use in a semi-arid region. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 371 (2019).

Li, M., Sun, H. & Zhao, R. A Review of Root Zone Soil Moisture Estimation Methods Based on Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 15, 5361 (2023).

Meng, X., Wang, H., Chen, J., Yang, M. & Pan, Z. High-resolution simulation and validation of soil moisture in the arid region of Northwest China. Sci. Rep. 9, 17227 (2019).

Peng, J. et al. A roadmap for high-resolution satellite soil moisture applications – confronting product characteristics with user requirements. Remote Sens. Environ. 252, 112162 (2021).

Zreda, M. et al. COSMOS: the COsmic-ray Soil Moisture Observing System. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 4079–4099 (2012).

Bell, J. E. et al. U.S. Climate Reference Network Soil Moisture and Temperature Observations. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 977–988 (2013).

Osenga, E. C., Arnott, J. C., Endsley, K. A. & Katzenberger, J. W. Bioclimatic and Soil Moisture Monitoring Across Elevation in a Mountain Watershed: Opportunities for Research and Resource Management. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2493–2503 (2019).

Dorigo, W. et al. The International Soil Moisture Network: serving Earth system science for over a decade. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 5749–5804 (2021).

Kerr, Y. H. et al. The SMOS Soil Moisture Retrieval Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 50, 1384–1403 (2012).

Entekhabi, D. et al. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) Mission. Proc. IEEE 98, 704–716 (2010).

Bartalis, Z. et al. Initial soil moisture retrievals from the METOP-A Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT). Geophys. Res. Lett. 34 (2007).

Njoku, E. G., Jackson, T. J., Lakshmi, V., Chan, T. K. & Nghiem, S. V. Soil moisture retrieval from AMSR-E. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 41, 215–229 (2003).

Vittucci, C. et al. SMOS retrieval over forests: Exploitation of optical depth and tests of soil moisture estimates. Remote Sens. Environ. 180, 115–127 (2016).

De, R. A. M. Retrieval of Land Surface Parameters using Passive Microwave Remote Sensing. Doctor (2003).

De Jeu Corresponding author, Ra. M. & Owe, M. Further validation of a new methodology for surface moisture and vegetation optical depth retrieval. Int. J. Remote Sens. 24, 4559–4578 (2003).

Pulliainen, J. & Hallikainen, M. Retrieval of Regional Snow Water Equivalent from Space-Borne Passive Microwave Observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 75, 76–85 (2001).

Santi, E. et al. An algorithm for generating soil moisture and snow depth maps from microwave spaceborne radiometers: HydroAlgo. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 3659–3676 (2012).

Rodell, M. et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 85, 381–394 (2004).

Naz, B. S., Kollet, S., Franssen, H.-J. H., Montzka, C. & Kurtz, W. A 3 km spatially and temporally consistent European daily soil moisture reanalysis from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Data 7, 111 (2020).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Sheffield, J., Goteti, G., Wen, F. & Wood, E. F. A simulated soil moisture based drought analysis for the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 109 (2004).

Dirmeyer, P. A. et al. GSWP-2: Multimodel Analysis and Implications for Our Perception of the Land Surface. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87, 1381–1398 (2006).

Ojha, N. et al. Assessment of SMOS Root Zone Soil Moisture: A Comparative Study Using SMAP, ERA5, and GLDAS. IEEE Access 12, 76121–76132 (2024).

Zeng, L. et al. Multilayer Soil Moisture Mapping at a Regional Scale from Multisource Data via a Machine Learning Method. Remote Sens. 11, 284 (2019).

Yao, P. et al. A long term global daily soil moisture dataset derived from AMSR-E and AMSR2 (2002–2019). Sci. Data 8, 143 (2021).

O, S. & Orth, R. Global soil moisture data derived through machine learning trained with in-situ measurements. Sci. Data 8, 170 (2021).

Karthikeyan, L. & Mishra, A. K. Multi-layer high-resolution soil moisture estimation using machine learning over the United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 266, 112706 (2021).

O, S., Orth, R., Weber, U. & Park, S. K. High-resolution European daily soil moisture derived with machine learning (2003–2020). Sci. Data 9, 701 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. A 1 km daily soil moisture dataset over China using in situ measurement and machine learning. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 5267–5286 (2022).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

McColl, K. A. et al. Extended triple collocation: Estimating errors and correlation coefficients with respect to an unknown target. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6229–6236 (2014).

Dorigo, W. A. et al. Global Automated Quality Control of In Situ Soil Moisture Data from the International Soil Moisture Network. Vadose Zone J. 12, vzj2012.0097 (2013).

Zeri, M. et al. Tools for Communicating Agricultural Drought over the Brazilian Semiarid Using the Soil Moisture Index. Water 10, 1421 (2018).

Beck, H. E. et al. Global-scale regionalization of hydrologic model parameters. Water Resour. Res. 52, 3599–3622 (2016).

Jucá, M. V. Q. & Ribeiro Neto, A. Remote sensing and global databases for soil moisture estimation at different depths in the Pernambuco state, Northeast Brazil. RBRH 27, e15 (2022).

Crow, W. T. et al. Upscaling sparse ground‐based soil moisture observations for the validation of coarse‐resolution satellite soil moisture products. Rev. Geophys. 50, 2011RG000372 (2012).

Moore, D. & J. Burch, I. G. & H. Mackenzie, D. Topographic Effects on the Distribution of Surface Soil Water and the Location of Ephemeral Gullies. Trans. ASAE 31, 1098–1107 (1988).

Zuo, X. et al. Spatial heterogeneity of soil properties and vegetation–soil relationships following vegetation restoration of mobile dunes in Horqin Sandy Land, Northern China. Plant Soil 318, 153–167 (2009).

Joshi, C. & Mohanty, B. P. Physical controls of near‐surface soil moisture across varying spatial scales in an agricultural landscape during SMEX02. Water Resour. Res. 46 (2010).

Zhang, J., Zhou, Z., Yao, F., Yang, L. & Hao, C. Validating the Modified Perpendicular Drought Index in the North China Region Using In Situ Soil Moisture Measurement. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 12, 542–546 (2015).

Guo, X. et al. Spatial Variability of Soil Moisture in Relation to Land Use Types and Topographic Features on Hillslopes in the Black Soil (Mollisols) Area of Northeast China. Sustainability 12 (2020).

Rasheed, M. W. et al. Soil Moisture Measuring Techniques and Factors Affecting the Moisture Dynamics: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 14 (2022).

O, S., Dutra, E. & Orth, R. Robustness of Process-Based versus Data-Driven Modeling in Changing Climatic Conditions. J. Hydrometeorol. 21, 1929–1944 (2020).

Meyer, H. & Pebesma, E. Predicting into unknown space? Estimating the area of applicability of spatial prediction models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1620–1633 (2021).

Scipal, K., Holmes, T., de Jeu, R., Naeimi, V. & Wagner, W. A possible solution for the problem of estimating the error structure of global soil moisture data sets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (2008).

Su, C.-H., Ryu, D., Crow, W. T. & Western, A. W. Beyond triple collocation: Applications to soil moisture monitoring. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 119, 6419–6439 (2014).

Xie, Q., Jia, L., Menenti, M. & Hu, G. Global soil moisture data fusion by Triple Collocation Analysis from 2011 to 2018. Sci. Data 9, 687 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. In-situ and triple-collocation based evaluations of eight global root zone soil moisture products. Remote Sens. Environ. 254, 112248 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Generation of global 1 km daily soil moisture product from 2000 to 2020 using ensemble learning. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 2055–2079 (2023).

Yuan, Q., Xu, H., Li, T., Shen, H. & Zhang, L. Estimating surface soil moisture from satellite observations using a generalized regression neural network trained on sparse ground-based measurements in the continental U.S. J. Hydrol. 580, 124351 (2020).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. A survey on deep learning tools dealing with data scarcity: definitions, challenges, solutions, tips, and applications. J. Big Data 10, 46 (2023).

Mittelbach, H. & Seneviratne, S. I. A new perspective on the spatio-temporal variability of soil moisture: temporal dynamics versus time-invariant contributions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 2169–2179 (2012).

Shi, Y. et al. Statistical analyses and controls of root-zone soil moisture in a large gully of the Loess Plateau. Environ. Earth Sci. 71, 4801–4809 (2014).

Pan, X., Kornelsen, K. C. & Coulibaly, P. Estimating Root Zone Soil Moisture at Continental Scale Using Neural Networks. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 53, 220–237 (2017).

Wang, X., Xie, H., Guan, H. & Zhou, X. Different responses of MODIS-derived NDVI to root-zone soil moisture in semi-arid and humid regions. J. Hydrol. 340, 12–24 (2007).

Schnur, M. T., Xie, H. & Wang, X. Estimating root zone soil moisture at distant sites using MODIS NDVI and EVI in a semi-arid region of southwestern USA. Ecol. Inform. 5, 400–409 (2010).

Liu, Y., Zha, Y., Ran, G., Zhang, Y. & Shi, L. SMRFR: A global multilayer soil moisture dataset generated using Random Forest from multi-source data. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27601035.v4 (2025).

Köppen, W. The thermal zones of the Earth according to the duration of hot, moderate and cold periods and to the impact of heat on the organic world. Meteorol. Z. 20, 351–360 (2011).

Jarvis, N. J. A review of non-equilibrium water flow and solute transport in soil macropores: principles, controlling factors and consequences for water quality. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 71, 279–302 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Analysis of the atmospheric direct dynamic source for the westerly extended WPSH and record-breaking Plum Rain in 2020. Clim. Dyn. 59, 1233–1251 (2022).

Fan, Y., Miguez-Macho, G., Jobbágy, E. G., Jackson, R. B. & Otero-Casal, C. Hydrologic regulation of plant rooting depth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 10572–10577 (2017).

Beck, H. E. et al. Evaluation of 18 satellite- and model-based soil moisture products using in situ measurements from 826 sensors. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 17–40 (2021).

Zheng, Y. et al. Evaluation of reanalysis soil moisture products using cosmic ray neutron sensor observations across the globe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 1999–2022 (2024).

Kerr, Y. H. et al. Soil moisture retrieval from space: the Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) mission. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 39, 1729–1735 (2001).

Hollmann, R. et al. The ESA Climate Change Initiative: Satellite Data Records for Essential Climate Variables. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1541–1552 (2013).

Martens, B. et al. GLEAM v3: satellite-based land evaporation and root-zone soil moisture. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1903–1925 (2017).

Vergopolan, N. et al. Field-scale soil moisture bridges the spatial-scale gap between drought monitoring and agricultural yields. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 1827–1847 (2021).

Qi, Q. et al. Mapping of 10-km daily diffuse solar radiation across China from reanalysis data and a Machine-Learning method. Sci. Data 11, 756 (2024).

Sachindra, D. A., Ahmed, K., Rashid, M. M., Shahid, S. & Perera, B. J. C. Statistical downscaling of precipitation using machine learning techniques. Atmospheric Res. 212, 240–258 (2018).

El Hajj, M., Baghdadi, N., Zribi, M. & Bazzi, H. Synergic Use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Images for Operational Soil Moisture Mapping at High Spatial Resolution over Agricultural Areas. Remote Sens. 9, 1292 (2017).

Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651–659 (2018).

Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. SOIL 7, 217–240 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52479045, 52279042), the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation Youth A-Class Project (2025AFA091), and the Key Research and Development Program in Guangxi (AB23026021). We appreciate the ISMN (https://ismn.earth/en/) and Zeri (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/xrk5rfcpvg/2) for their in-situ soil moisture data. We would also like to thank all the organisations for their public data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and G.R. designed the study. Y.L. wrote the paper. G.R. contributed to the analysis. Y.Z. discussed the results, reviewed and edited the paper. Y.Z. and L.S. edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Zha, Y., Ran, G. et al. SMRFR: A global multilayer soil moisture dataset generated using Random Forest from multi-source data. Sci Data 12, 1170 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05511-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05511-w