Abstract

Trajectory prediction is crucial for autonomous driving, necessitating robust models supported by comprehensive datasets. Most existing vehicle trajectory datasets often lack long-duration trajectories or high vehicle density, limiting their use in complex scenarios. In this paper, we construct a High-Density Semantic Vehicle Trajectory Dataset (HDSVT), collected via Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) over the Guangzhou Bridge. Our dataset is characterized by higher vehicle density, extended trajectory lengths, and semantic enhancements, which facilitate in-depth vehicle trajectory analysis. We have provided its original UAV videos. After processing these videos, our dataset consists of: (i) pixel coordinates of vehicle trajectory and lane lines in each video, (ii) corresponding geographic coordinates and (iii) semantic promotion for trajectories and motions. In this high-density, long-range trajectory context, the dataset captures diverse driving behaviors and complex multi-vehicle interaction. With its rich data on diverse driving behaviors and complex multi-vehicle interactions, this dataset is not only suitable for trajectory and motion prediction but also serves broader applications in driving decision-making, traffic management and long-term tracking of small objects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Vehicle trajectory prediction is gaining increasing importance in both academia and industry1, especially for autonomous robots and vehicles2. It plays a crucial role in the development of autonomous driving3. Predicting vehicle trajectories helps drivers4 make better decisions5 and avoid collisions, thereby contributing to traffic flow control6, reducing congestion, and improving road safety.

Recently, a large amount of methods have been developed for trajectory prediction1,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Typically, trajectory predictions are compared with ground truth trajectories sourced from various datasets. These datasets, often collected using sensors such as radar and cameras, are either manually annotated or automatically generated to capture sequences of vehicle movements. However, they often suffer from limitations such as limited trajectory lengths and counts, single scene types, and a lack of semantic enhancement. Detailed comparisons of our dataset with others are summarized in Table 1, where “density” refers to the average number of vehicles passing per second in each scene. Despite these efforts, a gap remains in the availability of datasets that fully encapsulate the complexity of real-world driving environments and present it in diverse formats. To tackle this issue, our dataset offers the following advantages:

-

Collection Ranges. We use Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to capture our videos, which enables the coverage of larger areas with minimal ground interference (e.g., pedestrians, non-motorized vehicles) and allows for more flexible changes in location.

-

Special Scene. Previous vehicle trajectory datasets were collected in settings like highways and crossroads. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to collect vehicle trajectories on a bridge, capturing unique motions that do not occur in other settings, such as entering or exiting a bridge, and dealing with special structures like “Y”-shaped intersections.

-

High Density and Long Time Record. We record vehicle trajectories ranging from 2 seconds to 130 seconds with high traffic density. This approach reveals long-term patterns and changes in driving behavior, such as speed variations and parking habits, and captures complex interactive behaviors necessary for managing sudden events like traffic congestion.

-

Semantic Promotion. While existing datasets typically provide trajectories in time series format only, we extract semantic features based on corresponding coordinates, expressing them in natural language format for vehicles’ trajectories and motions. Semantic trajectories offer richer data than mere location or speed, annotating specific behaviors like turning, lane changes and parking.

-

Separate Classification of Buses. Our dataset labels vehicles as cars and buses. Considering the distinct operational behaviors of buses compared to cars, classifying them separately based on “bus priority”21,22can enhance public transport efficiency. This approach supports the development of vehicle-infrastructure cooperative systems23, improves route adherence, and optimizes the use of bus lanes.

This dataset is collected on Guangzhou Bridge in Guangdong Province, China, during rush hours (8:00 AM to 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM to 6:00 PM) using Eulerian observations24. Seven cameras, mounted on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and depicted in Fig. 1, capture diverse states of traffic: UAV No.2 and 4 record vehicles on a flat road surface, while UAV No.1, 3, 5, and 6 capture vehicles entering and exiting the bridge. Notably, UAV No.1 is positioned near a gas station, UAV No.3 overlooks a “Y”-shaped intersection and UAVs No.5 and No.6 cover curved road segments associated with bridge entry and exit, while UAVs No.4 and No.7 capture scenes along straight road sections. These varied perspectives enhance the dataset by including both simple and complex road geometries as well as diverse interaction environments.

Our dataset significantly enhances trajectory prediction for autonomous vehicles, optimizing driving routes to improve safety at an individual level and enabling superior traffic management to mitigate accidents on a broader scale. This dataset supports diverse applications: it utilizes time-sequence data for basic modeling and facilitates short-term trajectory predictions suitable for dynamic driving scenes, and it extends to multi-time series forecasting for thorough traffic flow analysis. It integrates vehicle motion data in natural language format, suitable for Large Language Models (LLMs).

Collected via UAVs and refined through advanced computer vision techniques, our methodology ensures high accuracy in detecting and tracking small, long-duration objects across varied environments. This approach not only provides more refined motion analysis25, but also enhances algorithm robustness26 and cross-scene generalization capabilities27. For downstream tasks, it improves the precision of autonomous driving28, intelligent video surveillance29, and the interaction or navigation of robots30 in complex environments. This capability is crucial for developing robust systems that rely on minimal pre-training, such as few-shot and zero-shot learning, making the dataset invaluable for both immediate practical applications and extended research developments in multimodal technologies.

Methods

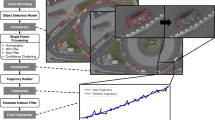

In this section, we detail the methods used to acquire three types of data formats via UAVs, encompassing both pixel and geographical coordinates, as well as their conversion into a motion natural language format. Specifically, these coordinates cover vehicle trajectories and lane lines within the same scene. The data are presented in two formats: Multivariate Time Series (MTS) for basic models and Natural Language (NL) for large language models. Based on these coordinates, we establish rules for vehicle motion classification. Additionally, we provide statistics on the number of trajectories and motions, enabling a comprehensive analysis of our dataset. The complete processing flow of this dataset is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Data Collection

The data is collected on the Guangzhou Bridge (Fig. 3), located in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China. The Guangzhou Bridge spans the Pearl River, connecting the Yuexiu, Haizhu, and Tianhe Districts of Guangzhou. Construction begins in April 1983, and the bridge opens to traffic in May 1985. An expansion and renovation project is completed on September 21, 2017. The bridge extends from Dongshan Street in Yuexiu District in the north to Chigang Street in Haizhu District in the south, with a total length of approximately 1,000 meters, a width of 24 meters and a height of about 6 meters. It is a bidirectional ten-lane trunk road designed for a speed of 60 km/h.

To obtain vehicle trajectories on the Guangzhou Bridge, we employ seven UAVs (model: DJI Phantom 4 RTK31) flying at a height of 120 meters. The UAV photography process for each aircraft position is depicted in Fig. 4. We select the area near Yujing Building, which experiences higher traffic density compared to the other side. Seven UAVs are positioned from north to south for filming. The total number of videos is 87, with a combined duration of 10 hours, 30 minutes, and 20 seconds, totaling 1,134,600 frames. On average, each video is 7.2 minutes long, covering 200 meters. The videos are recorded on November 27, 2017, and January 2, 2018, during rush hours (8:00 am to 10:00 am, 4:00 pm to 6:00 pm).

Extraction of Vehicle Trajectories from Original Videos

In this section, we outline the process of obtaining original vehicle trajectories from 87 UAV videos. This involves a two-stage approach: First, detecting vehicles within the videos. Second, tracking them to capture the trajectory coordinates for each vehicle. The detection phase incorporates both automatic and semi-automatic processes.

Detection

To obtain more accurate vehicle trajectory coordinates, we employ a two-step detection process: utilizing publicly available datasets and conducting manual annotation. We use the YOLO V832 algorithm to achieve vehicle detection. The algorithm follows these steps: Task Aligned Assigner. Before beginning sample identification, it is necessary to decode the network prediction values (Box and Cls) and the label’s Box and Cls to perform preliminary screening, fine screening, and elimination of excess. In the fine screening stage, we use Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU) to calculate the classification score, which determines whether the object is a car or a bus.

The loss function of YOLO V8 is define as:

The further information on the algorithm and its formulas discussed above, please consult the blog33.

-

Training with Open Datasets (Automated)

For the process of training vehicles detection, we initially employ two open datasets: VisDrone34,35 and UAVDT36,37, both of which can be used as UAV vehicles detection dataset. The VisDrone dataset comprises 56,878 UAV acquired images acquired by UAVs, with an equal division between RGB and infrared images. The UAVDT dataset, based on vehicle traffic content ingested by drones, contains approximately 8,000 image frames annotated with 14 attributes such as weather conditions, flight altitude, and vehicle category.

We summarize these labels into two categories for cars and buses to facilitate the task. After training with the aforementioned datasets, the partial validation results are as follows: As illustrated in Fig. 5, the majority of vehicles in the videos are detected. However, several issues remain, such as missed detections due to vehicle colors blending with lanes or the ground, obstructions (trees, camera crossbars), overlapping bounding boxes, and erroneous detections involving other objects like buildings, lane markings, or boats.

-

Manual Data Annotation (Semi-Automated)

To tackle this issue, we employed the labelImg38 to re-annotate the images from 87 videos. Furthermore, we randomly extracted thousands of images from seven UAV positions over two years (2017 and 2018) and imported them to labelImg (Fig. 6). In Fig. 7, the primary task involves verifying for missed detections (due to environmental factors or color similarities with the road) or incorrect labels (such as other objects misidentified as vehicles, highlighted in red squares) and supplementing overlooked bounding boxes.

Subsequently, these images are divided in an 8:1:1 ratio (train: validation: test) for the YOLO V8 model, based on parameters derived from the two public datasets (VisDrone34,35 and UAVDT36,37). To more effectively demonstrate the improvements from manual labeling, we use scenes of greater complexity and higher density. The partial final detection results are presented in Fig. 8.

Tracking

Following the methods describes in the previous section, we detect all vehicles in the videos. The subsequent step involves tracking these vehicles to obtain their trajectories.

Before tracking, selective masking is applied to each UAV’s capture area to enhance trajectory extraction accuracy and clarity. This process isolates roads with unidirectional, high-density traffic and typical movement patterns by masking specific lanes directed towards the ZhongGuan building and extraneous features such as buildings, rivers, and vegetation. Segmentation of targeted lane sections and the surrounding environment is performed using the “create polyline” tool, as depicted in Fig. 9. The final tracking regions are shown in Fig. 10.

The selected regions for tracking after masking. The UAV position is indicated in the lower right corner of each subfigure (No.*). Here, lanes with higher traffic density are chosen for tracing. The method of masking in figures No.5 and No.6 aims to capture more specific movements, such as entering or exiting the bridge.

Subsequently, we employ BoT-SORT algorithm39 for tracking purposes, which presents a robust tracking solution. It combines the advantages of motion and appearance information, incorporates camera-motion compensation, and utilizes an enhanced Kalman filter state vector for improved accuracy, and fuses Intersection over Union (IoU) with Re-Identification (Re-ID) features. This approach employs the minimum value of each element in the matrices as the final value for the cost matrix C:

where Ci,j denotes the element in the ith row and jth column of cost matrix C. The fusion pipeline of IoU and Re-ID can be formulated as:

Here \({d}_{i,j}^{* }\) represents the distance between the predicted and detected bounding boxes under different metrics (with the symbol * representing either IoU or cosine distance), and θ* denotes the threshold for the corresponding metric. The visualization of this tracking process appears in Fig. 11, where trajectory lines are displayed behind each vehicle, indicating cars (yellow boxes) and buses (red boxes). The coordinates obtained through BoT-SORT constitute our preliminary vehicle trajectories. For a more comprehensive and accurate representation, these aspects are elaborated upon in the following section.

Post-Processing of Vehicle Trajectories: Pixel Coordinates

After acquiring the vehicle trajectories from 87 videos, we obtain them in the form of original pixel coordinates (x, y). However, these original data present some issues. So this section delineates the post-processing undertaken for these trajectory data and the acquisition of lane line coordinates in each video. The trajectory post-processing comprises three steps: data completion, label unification and trajectory smoothing. Lane line coordinates are meticulously obtained through manual annotation.

Completion of Missing Data

Due to factors like tree occlusion and drone instability, some vehicle trajectory data may be missing position coordinates. In the context of autonomous driving, the completeness of data is crucial for operational safety. Completing missing data allows the system to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the environment and make more accurate predictions, particularly in scenarios involving overtaking, emergency braking, or obstacle avoidance. This helps maintain the continuity and accuracy of the models, thereby enhancing their ability to predict and adapt to the behaviors of other road users.

Vehicle trajectory data are regarded as multivariate time series, where each coordinate point (x, y) corresponds to a specific timestamp t. In this scene, the purpose of interpolation is to ensure temporal continuity, rather than addressing independent changes in both spatial x and y coordinates. Consequently, we typically perform linear interpolation40 on the x and y coordinates separately, but in relation to time t. This process essentially creates a straight line between the two points in question as illustrate in Fig. 12. Specifically, let \(({x}_{t}^{k},{y}_{t}^{k})\) represent the position coordinates of the k-th vehicle at time t To determine its position, we use linear interpolation based on the coordinates at times (t − 1) and (t + 1) in both the x and y dimensions. For example, we apply this method to the x coordinate, and similarly to the y dimension.

For k-th vehicle at a time t within the interval (t − 1, t + 1), the x value along the straight line is derived using the slope equation41:

Here, we apply the case of linear (first-degree polynomial) interpolation. Solving this equation for x, the unknown value at time t, yields

The error of this interpolation denoted as RT, is defined as \(\,{R}_{T}=f\left(x\right)-p\left(x\right)\), where p(x)is the polynomial as defined in Equation (1), replacing \({x}_{t}^{k}\) with f(t). Rolle’s theorem42 can be used to prove that if f possesses a continuous second derivative, the error is bounded by

From another perspective, Equation (2) suggests that for vehicle trajectories approximating straight lines rather than curves, simple linear interpolation provides an almost optimal approximation.

Unification of Labels

In this part, we need to standardize their labels to achieve the following advantages: enhance label stability and reduce fluctuations in trajectory prediction. Minimize noise and errors due to complex conditions, such as vehicle merging, where UAVs might erroneously assign different IDs to the same vehicle at different times. Inconsistent labeling of the same vehicle can impair the predictive model’s performance. Furthermore, it can enhance the reliability of autonomous driving decision-making. To achieve these objectives, we apply the “80% principle”, where the final label is determined by the most frequent label, which accounts for at least 80% of the labeling for a given vehicle.

Smoothing of Trajectory Data

Thus far, we obtain complete vehicle trajectories, each assigned a unique label. To enhance downstream tasks such as trajectory prediction, we smooth each trajectory. Accurate trajectory prediction is crucial for autonomous driving systems to effectively plan paths and make informed driving decisions. Smoothing the trajectory removes random noise from the data, thereby enhancing the accuracy of future position predictions and the overall reliability of the system. Additionally, it can reduce trajectory inaccuracies caused by UAV errors, occlusions, and similar factors. This process not only improves data quality but also enhances the efficiency and robustness of the associated models.

Based on the features of vehicle trajectories, we apply mean filtering43 to smooth the completed trajectories. From a mathematical standpoint, it ensures that the trajectories, once smoothed by mean filtering, adhere to the central limit theorem44. That is, as the number of trajectories increases, the mean position of the trajectory coordinates will tend toward a Gaussian distribution. This is advantageous for statistical analysis and subsequent predictive processing. From an engineering perspective, mean filtering can effectively preserve the overarching trend and shape of the trajectories, as it averages the positions within a specified time window to smooth the data. This highlights the general direction and shape of the motion, undisturbed by short-term fluctuations or noise, and allows for control over the smoothness by adjusting the window size. Here, we select a window size that is equal to the frame rate (frames per second).

For the specific vehicle trajectory data, each point subjected to mean filtering is calculated using the average length of each half-window preceding and following it. Taking the x coordinate as an example, and applying the same method to the y coordinate,

we denote the pixel position of the k-th vehicle at the t-th timestep as \({x}_{t}^{k}\). The smoothed point is represented by the symbol \(\widetilde{{x}_{t}^{k}}\). The smoothed value \(\widetilde{{x}_{t}^{k}}\) is calculated using the following formula: “3” is number of the equation, not superscript.

where Nw denotes the window size for mean filtering. In this instance, we set it to 30 for each frame of the videos. For points that are less than the window size Nw, such as the start and end points, we use an adaptive window defined as:

where \({x}_{\widehat{t}}^{k}\) represents the position of the k-th vehicle at the \(\widehat{t}\) timestep. Figure 13 illustrates this process for a standard case Fig. 13(a) and the treatment of very sharp corners Fig. 13(b).

After post-processing the data using the aforementioned methods for data completion, unified labeling, and smoothing, we select seven images from the respective positions of each UAV to illustrate the final pixel trajectory coordinates, as shown in Fig. 14.

Manual Lane Line Annotation

Extracting lane lines is crucial for autonomous systems because they are part of the input to trajectory prediction and path planning. Overall, Lane lines delineate potential vehicular travel paths, serving as fundamental constraints in determining vehicle trajectories. Existing models, such as ALAN45, LaneGCN46, Gohome47, Lapred48, LAformer49 etc. incorporate lane lines as features. Information on the number, direction (including one-way traffic), curvature, and categorization of lane lines is crucial in predicting future vehicle positions. Moreover, lane lines constitute basic traffic rules that govern vehicle behavior, with dashed and solid lines indicating the permissibility of lane changes. In multi-agent (vehicle) scenes, lane lines offer a framework to assess relative positioning and potential interactions.

Existing public datasets for lane line detection, including CULane50, VPGNet51, 3D Lane Synthetic52, Lane Instance Segmentation53, DET54, and Curve Lanes55, feature vehicular radar-based perspectives (Fig. 15), distinct from our UAV’s aerial viewpoint. Consequently, accurate delineation of lane lines can be problematic. To address this, we utilize the annotation tool LabelMe56 for its adaptability, marking each lane line across the complete video sequence. Given the unique shape characteristics of lane lines, we adopt a linear annotation approach for labeling, as illustrated in Fig. 16. This method ensures the precise capture of each lane line’s coordinate positions.

Latitude and Longitude Coordinates

By converting pixel coordinates into geographical coordinates of latitude and longitude for each vehicle’s trajectory, we unlock significant advantages. Geographical coordinates provide an accurate real-world mapping, which is crucial for practical navigation and positioning. They also allow for the seamless fusion of image data with other geospatial information, like GIS and weather data, enhancing trajectory predictions with a more comprehensive environmental context. Additionally, these coordinates are fully compatible with the Global Positioning System (GPS), supporting real-time tracking and predictive systems for autonomous vehicles. Finally, the conversion facilitates the broader application of this data in various sectors, including UAV surveillance, traffic management, and emergency services.

To obtain longitude and latitude coordinates (hereinafter “geographic coordinates”), we demonstrate a promotion illustrated in Fig. 17. For the coordinates transfer, we use the first four lines, reserving the remainder for a subsequent subsection on vehicle motions. The visual results of this promotion are depicted in Fig. 18. The coordinates transfer process involves calculating meters per pixel, converting pixel coordinates to world coordinates, and subsequently transforming these into geographical coordinates. We apply this process to vehicle trajectory transfer, similarly to lane lines.

This template facilitates the conversion from pixel coordinates to geographic coordinates and vehicles’ motions. The “6” specified in the first line indicates the measurement unit in meters, adhering to the JTG B01-2014 standard57. The coordinates \({x}_{1}^{* },{y}_{1}^{* }\) mentioned in lines 2 and 5, identify the upper left corners of designated areas for lanes and stations, respectively. Conversely, the subscript “2” denotes the lower right corners. The reference point coordinates are denoted by x*, y* in lines 3 and 4. The unit of measure for longitude and latitude is expressed in degrees. Lines 6 and 7 represent the boundaries for exiting and entering the bridge, respectively. If a position lacks either boundary, the missing value should be filled with “0”.

The process of obtaining pixel coordinates and corresponding vehicle motions. These specific coordinates are achieved using LabelMe56. The “Reference Line” and “Lane Line” are used for converting pixel coordinates to geographic coordinates, while other elements are used for analyzing vehicle motion.

To calculate the actual distance represented by each pixel, we utilize the standard length of a dashed lane line, which is 6 meters according to JTG B01-201457. We denote this length as Ld. The calculation is expressed as follows:

where \({x}_{* }^{{\rm{Lane}}}\) and \({y}_{* }^{{\rm{Lane}}}\) represent the pixel coordinates of the lane lines in each video. We employ different annotated pixel coordinates because the UAV shooting angle and the distance to the ground vary across videos. MPP stands for Meters Per Pixel.

Pixel coordinates are two-dimensional, measured in pixels, and are utilized for tasks such as image analysis and object recognition. World coordinates, on the other hand, are three-dimensional and represent the actual size, position, and relationship between objects, playing a crucial role in computer graphics, robotics, and geographic information systems. To ascertain the distance between vehicles, we rely on the MPP value as defined in Equation (4), which indicates the number of meters each pixel represents. By applying this value, we can convert a vehicle’s position in the image to its actual distance. The process is as follows:

Here xk carries the same meaning as in Equation (3); we omit the subscript t to represent all time steps. The notations \(\widehat{{x}^{k}}\) and \(\widehat{{y}^{k}}\) denote the world coordinates. Unlike world coordinates, geographic coordinates (such as WGS 8458) are employed to represent the longitude and latitude of a location on a global scale. They are crucial for cartography, location services, navigation, and other applications that necessitate accounting for Earth’s curvature. To ensure trajectory data is accurately positioned on a global scale, we aggregate diverse origin data (such as satellite images and meteorological data), providing additional features for trajectory prediction, traffic monitoring, and driving guidance. We convert world coordinates into geographic coordinates using the following transformation, as shown on the left side of Equation (5):

Here, MPD stands for Meters Per Degree, while Lat and Lon refer to latitude and longitude, respectively, as abbreviated in line 4 of Fig. 17. The values of MPDLat and MPDLon in Equation (6) are calculated as follows:

In the given context, Re represents the Earth’s equatorial radius, and e2 denotes the square of the Earth’s eccentricity. The term “rad” refers to the function that converts angles from degrees to radians. Here, Re equals 6,378,137 meters and e2 is 0.00669437999014; these values are predicated on the assumption that the Earth conforms to the WGS-84 ellipsoidal model58. We refrain from using an average value because the location of the video is known. MPDLon, which is defined as follows:

In this context, MPDLat and MPDLon depend solely on the reference point latitude yLat, because meridians converge at the poles and the separation between meridians changes with latitude, regardless of longitude. Additionally, the cosine of the latitude affects the distance calculation. Correspondingly, the distance between lines of latitude is contingent upon latitude since these lines are parallel circles to the equator, and their circumference is a function of latitude alone.

In Equation (6), geographic coordinates are typically projected onto a two-dimensional plane, with longitude assigned to the x-axis and latitude to the y-axis. This convention aligns with common map projection methods, including the Web Mercator projection within a Cartesian coordinate system, exemplified by Google Maps59. The sequence of writing latitude before longitude in documentation does not affect their corresponding axes. The procedure to determine geographic coordinates for a reference point (yLat and xLon) utilizes Google Earth59, as depicted in Fig. 19.

The process of obtaining geographic coordinates for reference points. Each point, captured in different videos, is determined using Google Earth59.

Vehicle Trajectory Data Analysis

We compile statistics on the length of each vehicle’s trajectory coordinates as captured by seven different UAVs over two years. This analysis helps us to comprehend the utilization of the road network over a specified time frame and provides insights for infrastructure enhancements, such as the necessity for additional roads, improved intersection layouts, or expanded public transportation options. Furthermore, examining the duration of vehicle tracks aids autonomous driving systems in better understanding and anticipating traffic trends and behaviors, thereby enhancing the precision of decision-making and route planning. The findings are presented in Fig. 20.

Length statistics of vehicle trajectories captured by seven UAVs in 2017 (left) and 2018 (right). The horizontal axis represents trajectory duration, with each tick indicating the median value of the interval. The vertical axis displays values transformed by 20\(\log (x)\) for clearer numerical representation. Each block indicates the number of trajectories.

To present the data distribution with clarity, a logarithmic scale is used for the vertical axis, and the number of vehicle trajectories is indicated on each block corresponding to an UAV position. Our statistical analysis shows that the dataset covers a wider temporal range of vehicle trajectories, from 2 to 130 seconds, which surpasses the duration found in other open vehicle trajectory datasets. Notably, the year 2018 witnessed an increase in the number of trajectories across most time intervals, indicative of either higher activity levels or enhanced data collection techniques. Moreover, a comparison between 2017 and 2018 data reveals a significant uptick in longer-duration trajectories, hinting at increased operational complexity or specific activity types. These trends imply that the expansion of Guangzhou Bridge progressively alleviates traffic congestion issues over time.

Motion Semantic Promotion for Large Language Models

From the pixel and geographic (longitude and latitude) coordinates of each vehicle and lane line, we derive time series data, suitable for multivariate time series or trajectory prediction methods. In this section, we introduce an alternative data format suitable for Large Language Models (LLMs), which transforms the coordinates into a natural language format. This format comprises two parts: the vehicle’s pixel coordinates described in natural language, and the motion information derived from them.

Translating time series data into natural language offers several advantages.

-

(1)

Enhanced Data Understanding: Natural language formats help non-technical stakeholders like transportation planners understand vehicle movement data easily, without the complexity of temporal coordinates. This facilitates more effective decision-making60,61.

-

(2)

Simplified Data Analysis: Using intuitive labels such as “straight”, “turn left” or “enter/exit the station” simplifies traffic flow analysis and pattern recognition, accelerating classification and clustering processes62.

-

(3)

Enhanced Multimodal Data Fusion: Natural language can be integrated with visual or audio data for advanced multimodal analysis63,64, enhancing applications like Augmented Reality65 (AR) navigation systems.

-

(4)

Application of Language Models: It enables the use of language models like BERT66 and GPT67 for effective forecasting and analysis68 including autonomous driving69 and vehicle voice navigation68,70. For example the LMTraj model61 showcases how language-based approaches can accurately predict trajectories, highlighting the capability of language models in handling complex data sequences.

Pixel Coordinate Promote

First, we introduce the process of transferring vehicle trajectories and lane line pixel coordinates into natural language format. As in previous sections, we use vehicle trajectories as examples and apply the same method to lane lines. We choose pixel coordinates over geographic coordinates because pixel coordinates are shorter, which enhances the processing speed for LLMs. We draw on the experience of PromptCast68 in this part. After extracting the coordinate values using regular expressions, the transfer result involves averaging the coordinates to represent a point per second (notated as “Sec” index), as follows:

where Nw has the same value and implication as in Equation (3). The whole vehicle trajectory output includes the ID, label, and pixel coordinates for each vehicle, recorded every second. In contrast, the lane lines provide their pixel coordinates in natural language.

Vehicle Motion

Next, we classify vehicle motions based on pixel coordinates, presenting them in natural language, which is more intuitive and easier to explain than mere numerical data or unlabeled classifications. This approach is particularly useful in elucidating model decisions. By performing detailed text classification of motions, the model learns to recognize complex patterns of driving behavior and environmental interactions, thereby enabling the autonomous driving system to respond more accurately in complex traffic scenarios.

According to the motion classification standards of the Waymo dataset71 and features of our data, we define a 2-second interval as a motion unit. If a vehicle travels less than 1 meter within this interval, it is classified as “Stationary”. For other motions, classifications are illustrated in Fig. 18 for judge whether enter the bridge (car and bus) or enter the station (only) for bus, while Fig. 21 is the overall classification criteria. We use the angular relationship of approximately 30∘ to make preliminary motion classifications (subtle or broad). A complete explanation of the abbreviations is provided in Table 2.

Standard for vehicle motion classification. Here, α represents the orientation angle of each vehicle. For subtle motion (α < 30°), Dl denotes the lateral displacement of each dashed lane line as specified in JTG B01-201457. For broad motion (α > 30°), if the k-th motion differs from the (k + 2)-th, the (k + 1)-th motion changes as indicated by the corresponding arrow. The abbreviations in the diagram are defined in Table 2. “No.*” refers to the UAVs’ position numbers. “Station” and “Bridge” denote movement boundaries, as illustrated in Fig. 17.

For subtle motion, the distance between two dashed lines is 3.75m, as specified by JTG B01-201457. For broad motion, classification involves three situations. The “Station” indicated by the first arrow relates to the bus station presence, determined through line 6 of Fig. 17. If a bus station is present, the direction of vehicle travel near the station dictates the action: turning left to exit the station, and the opposite for entering. The “Bridge” marked by the third arrow, utilizes lines 6 and 7 in Fig. 17 to ascertain whether vehicles exit or enter the bridge upon crossing the specified lines at these positions. The second arrow addresses situations outside these two cases: if the (k + 2)-th motion differs from the preceding continuous k motions (indicative of turning left or right), then the (k + 1)-th motion is adjusted to execute the turn.

Motion Analysis

We analyze the motions record in 2017 and 2018 for vehicles labeled as cars and buses, as depicted in Fig. 22. The analysis encompasses the following aspects:

-

1.

Main Motion Differences:

-

Car: Predominantly straight driving (87.0%), consistent with typical urban and high-speed traffic patterns.

-

Bus: A significant proportion of time in a static state (81.5%), reflecting frequent stops at stations and potential delays due to traffic congestion or yielding to other vehicles.

-

-

2.

Importance of Secondary Motions:

-

Bus: Entry and exit behaviors account for 32.3% of actions, highlighting their impact on route planning and station design. Lane changes and turns are infrequent, suggesting a relatively fixed route with limited lateral movements.

-

Car: Lane changes constitute 21.1% of actions, indicating frequent adjustments in complex traffic flows. Though turns, such as those required for entering and exiting bridges, are less common, they remain critical for navigating specific road conditions and making strategic driving decisions.

-

Motion statistics for cars (above) and buses (below) across 2017 and 2018. The left pie chart illustrates the primary motions associated with each label, while the smaller pie chart on the right depicts secondary motions. Legends for each pie chart are positioned to the right, enclosed within a gray frame.

Data Records

Due to the large size of the full dataset, we provide a mini demonstration set comprising videos from seven UAV positions for experimental and educational purposes, available72 at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27191856. Each video is named according to the UAV’s position (e.g., 1.mp4 represents the first UAV), offering a clear overview of the dataset’s spatial coverage. The complete dataset, covering all UAV positions over two years (totaling 238 GB), is available via Baidu Netdisk at: https://pan.baidu.com/s/1c8LsYJZFcbhUfdNfezzf0w?pwd=v6r8.

All the trajectory data, including: (i) pixel coordinates of vehicle trajectory and lane lines in each video, (ii) corresponding geographic coordinates and (iii) semantic promotion for trajectories and motions, are deposited at Figshare72 and Openl https://git.openi.org.cn/WendyTwo/HDSVT/datasets.

Data Acquisition

To evaluate the impact of the Guangzhou Bridge widening project on traffic conditions, FUNDWAY TECHNOLOGY Guangdong Province conducted mission flights over the Tianhe and Haizhu districts of Guangzhou City for traffic data collection.

In this operation, at least eight DJI Phantom RTK 4 models are utilized. The designated shooting area includes the following coordinates: E\(11{3}^{\circ }1{9}^{{\prime} }14.6{2}^{{\prime\prime} }\) N\(2{3}^{\circ }{7}^{{\prime} }29.4{4}^{{\prime\prime} }\), E\(11{3}^{\circ }1{9}^{{\prime} }24.0{6}^{{\prime\prime} }\) N\(2{3}^{\circ }{7}^{{\prime} }49.4{4}^{{\prime\prime} }\), E\(11{3}^{\circ }1{9}^{{\prime} }24.0{6}^{{\prime\prime} }\) N\(2{3}^{\circ }{5}^{{\prime} }55.7{6}^{{\prime\prime} }\), E\(11{3}^{\circ }1{9}^{{\prime} }14.6{2}^{{\prime\prime} }\) N\(2{3}^{\circ }{5}^{{\prime} }55.7{6}^{{\prime\prime} }\), forming a quadrilateral. The UAVs operated below an altitude of 120 meters. Take-offs and landings were conducted from two sites: the main site west of Jinsui Road in Tianhe District (E\(11{3}^{\circ }1{9}^{{\prime} }18.2{7}^{{\prime\prime} }\) N\(2{3}^{\circ }{7}^{{\prime} }48.4{2}^{{\prime\prime} }\)); and an alternate site east of Guangzhou Avenue South Road in Haizhu District (E\(11{3}^{\circ }1{9}^{{\prime} }19.8{8}^{{\prime\prime} }\) N\(2{3}^{\circ }{5}^{{\prime} }57.0{3}^{{\prime\prime} }\)). Videos occur on November 27, 2017, and January 2, 2018, during rush hours (8:00 am to 10:00 am and 4:00 pm to 6:00 pm), resulting in 87 videos totaling 10 hours, 30 minutes, and 20 seconds across 1,134,600 frames.

Throughout the flight operations, the UAVs abide by safety protocols by declaring flight plans as required, notifying control of flight dynamics, submitting to the oversight of the aviation control department, and signing flight safeguard agreements with the relevant authorities to ensure safety during the event.

Data Format

Our Guangzhou Bridge Semantic Trajectory Dataset comprises three major components and six subparts. The major components include pixel and geographic coordinates, along with promotions for Large Language Models (LLMs). The subparts consist of vehicle trajectories and lane lines represented in two coordinate systems for time series format, as well as vehicle trajectories and motions formatted in natural language. These elements are organized into six folders, totaling 5.46 GB, as depicted in Fig. 23.

Data structure of the Guangzhou Bridge Semantic Trajectory Dataset. The dataset comprises three major components: pixel and geographic coordinates for each vehicle and lane line; promotions for Large Language Models (LLMs) are provided by vehicle motions and trajectories derived from pixel coordinates. The context provided in brackets denotes the corresponding folder name.

Files within the dataset are named according to the following naming convention: type_year_No._timeL/S.file. Here “type” specifies the content (further details provided later). “time” is recorded using a 24-hour clock. Durations under 5 minutes are tagged as ‘S’ (short), and durations exceeding this threshold are tagged as ‘L’ (long). Files are formatted in either CSV csv (for time-sequenced data) or TXT (for natural language data). txt

Pixel & Latitude and Longitude Coordinates

Pixel and latitude and longitude (geographic) coordinates are structured into two components: vehicle trajectories and lane lines, labeled as “Traj” and “Line” respectively in CSV file formats. To avoid confusion, these are stored in separate folders named Pixel Coordinates and Geographic Coordinates. For example, the file structure is represented as Pixel Coordinates/Traj_2017_1_1645L.csv and Geographic Coordinates/Line_2017_1_1645L.csv.

-

Trajectory. The first two rows of each CSV file record the total number of frames (length) and the vehicle label (car or bus). The third row lists the vehicle number as Vehicle_ID, and the fourth row details the position coordinates in each frame. To visually distinguish between the two types of coordinates, we use purple for pixel (above the points) and orange for geographic coordinates (below the points), as shown in Fig. 24.

Fig. 24 The pixel and geographic coordinates for each vehicle are illustrated using selected continuous points. Pink points indicate specific coordinates, while a dashed blue line depicts the trajectory. To distinguish between coordinate types, purple is used above each point for pixel coordinates and orange below for geographic coordinates.

-

Line. Each lane line CSV file starts with the first column indicating the total labeled points of each lane line, as depicted in Fig. 16. The term “line4Y” in the last row denotes the Y-shaped lane line found at UAV position No.1.

Promotion for Large Language Models

To adapt our dataset for use with Large Language Models (LLMs), we provide natural language descriptions based on the pixel coordinates of each vehicle, detailing vehicles’ motion and trajectory. These are typed prefixes such as “Mon” (stored in the Motion folder) and “Pro” (stored in the Pix folder), both formatted as text files. For example: Mon_2017_1_1645L.txt and Pro_2017_1_1645L.txt.

For the motion classification of each vehicle, we align with the standards of the Waymo dataset71, with specific motions detailed in Fig. 21. We utilize text templates featuring function slots73 as follows:

The Vehicle_<ID> Type is <car/bus> with a total of <No.> motions, which are: …

In this template, <ID> is the unique identifier for each vehicle, <car/bus> specifies the type of vehicle, and <No.> represents the total number of recorded motions. The ellipsis is used to indicate a list of detailed motions such as Stationary, Straight, Turn Direction, and others, with abbreviations and their meanings detailed in Table 2. Visual representation of this content is shown in Fig. 26.

For the natural language descriptions of each vehicle trajectory, we employ the PromptCast methodology68 to transform time sequences into textual format, akin to the vehicle motion documentation depicted in Fig. 25. We record the average position at each current timestep, measured in seconds, to ensure a precise and succinct expression. In our dataset, the video captures 30 frames per second.

Technical Validation

This section evaluates the quality of our dataset. The processing of our video dataset includes detection, tracking, and post-processing stages. In the initial stages, we obtain the original vehicle trajectory data, for which we apply standard vision metrics. Subsequently, we compare the post-processed results with the original data to evaluate enhancements and accuracy.

Detection Metrics

The detection indicators primarily assess the performance of vehicle detection algorithms in identifying the locations and types of vehicles. The metric used is the detection accuracy index, which compares the “ground Truth” (GT) with the detected labels. The GT is acquired similarly to the semi-manual data annotation during the detection process, utilizing the labelImg38 tool, as depicted in Fig. 6.

We present the values of quantitative indicators in Table 4. The definitions of these metrics are detailed as follows74, with standard abbreviations such as TP, TN, FP, and FN illustrated in Fig. 27. The corresponding confusion matrix for the testing data is presented in Table 3.

-

Accuracy: Accuracy is the most straightforward metric for evaluating performance, representing the proportion of correct predictions out of all predictions as:

$$Acc=\frac{{\rm{TP}}+{\rm{TN}}}{{\rm{TP}}+{\rm{TN}}+{\rm{FP}}+{\rm{FN}}}.$$In classification tasks, accuracy is determined by the number of correctly predicted samples (car or bus) relative to the total sample count. With an accuracy rate of 99.950%, our result demonstrates exceptionally high precision in its predictions, with minimal errors.

-

Precision: Determining the proportion of positively predicted data that is correctly positive. “Pre-car” and “Pre-bus” represent the precision values for each classification. It is defined as:

$$Pre=\frac{{\rm{TP}}}{{\rm{TP}}+{\rm{FP}}}.$$(7)For example, the proportion of cars accurately identified as cars rather than buses. With a high precision of 99.777%, our result demonstrates that almost all vehicle predictions are accurate, with very few false positives. Precision by Class:

-

1.

Value results: Pre_car – 99.961%; Pre_bus – 99.728%.

-

2.

Index Illustrate: These figures respectively quantify the model’s precision in identifying cars and buses. Both values are close to 100%, signifying near-perfect accuracy for car detection, which ensures reliability in classifying specific vehicle types.

-

1.

-

Recall: Recall, also known as sensitivity, measures the proportion of actual positive classes that are correctly identified by the model as positive:

$$Rec=\frac{{\rm{TP}}}{{\rm{TP}}+{\rm{FN}}}.$$(8)This metric indicates the model’s ability to identify all potential positive classes. Specifically, a recall rate of 99.456% demonstrates that the model can successfully identify the vast majority of positive samples: either cars or buses, with minimal missed detections.

-

Mean Average Precision (mAP): mAP is a widely utilized metric in object detection that calculates the average precision across various IoU (Intersection over Union) thresholds. The IoU is a measure that quantifies the overlap between predicted and actual bounding boxes.

Two-category confusion matrix. Definitions: TP: The sample is positive, and the model correctly predicts positive. FP: The sample is negative, but the model incorrectly predicts positive. TN: The sample is negative, and the model correctly predicts negative. FN: The sample is positive, but the model incorrectly predicts negative.

-

1.

mAP50: This indicates the mAP at an IoU threshold of at least 0.5, providing a relatively lenient criterion for match accuracy.

-

2.

mAP50-95: This represents the mean mAP calculated at all IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.96, typically in increments of 0.05. It offers a more stringent and comprehensive assessment of model performance.

A high mAP50 score of 99.491% demonstrates the model’s robust performance at lower IoU thresholds. Although the mAP50-95 score has slightly decreased to 92.359%, it remains impressively high, ensuring precise classification of vehicles such as cars and buses without confusion.

-

F1-score: This statistical metric measures the accuracy of classification models and is defined as the harmonic mean of precision in Equation (7) and recall in Equation (8):

$${F}_{1} \mbox{-} score=2\times \frac{Pre\times Rec}{Pre+Rec}.$$The F1-score is particularly effective in scenarios with imbalanced categories as it balances the influence of false positives and false negatives. Our F1-score of 0.99616 indicates high precision and recall, signifying minimal false positives and false negatives.

The visualizations in Fig. 28 demonstrate the high quality of our dataset in the context of vehicle classification. In the F1-Confidence curve (Fig. 28(a)), our dataset achieves an F1 score near 0.99 at a 0.5 confidence threshold, reflecting a balance of precision and recall indicative of accurate data. The Precision-Confidence curve (Fig. 28(c)) illustrates increasing precision at higher confidence levels, showcasing minimal misclassifications—a testament to the dataset’s reliability. Meanwhile, the Recall-Confidence curve (Fig. 28(d)) shows high initial recall, decreasing with higher thresholds, confirming the sensitivity of the dataset. The Precision-Recall curve (Fig. 28(b)) further validates the consistent precision throughout varying recall levels, underscoring the robustness of our dataset for vehicle detection tasks.

Tracking Metrics

Tracking metrics evaluate detection accuracy and identity maintenance. Just as in achieving detection metrics, we generate annotated Ground Truth (GT) using the DarkLabel75 tool, depicted in Fig. 29. We assess our tracking results using TrackEval76.

We present the values of these key metrics77,78,79 in Table 5. The specific definitions of these metrics are detailed below. For clarity, we visualize some terms used in these metrics77 (such as TP, TPA, etc.) in Fig. 30.

-

HOTA (Higher Order Tracking Accuracy): It measures the balance between detection and association accuracy, which is crucial for effective tracking performance. The formula is given by:

$${{\rm{HOTA}}}_{\alpha }=\sqrt{\frac{{\sum }_{c\in \left\{{\rm{TP}}\right\}}{\mathscr{A}}\left(c\right)}{\left|{\rm{TP}}\right|+\left|{\rm{FN}}\right|+\left|{\rm{FP}}\right|}}\,,\,{\rm{where}}\,{\mathscr{A}}\,\left(c\right){\rm{is}}\,{\rm{defined}}\,{\rm{as}}\,{\mathscr{A}}\,\left(c\right)=\frac{\left|{\rm{TP}}A\left(c\right)\right|}{\left|{\rm{TP}}A\left(c\right)\right|+\left|{\rm{FN}}A\left(c\right)\right|+\left|{\rm{FP}}A\left(c\right)\right|}.$$(9)In this context, TP, FN and FP follow the conventional definitions used in detection metrics, as shown in Fig. 27. The alignment measure \({\mathscr{A}}\) assesses the consistency between the ground truth trajectory (gtTraj) and the predicted trajectory (prTraj) at the TP c. The parameter α serves as a threshold, influencing the sensitivity of the metric to detection and association errors. The average HOTA across all evaluated scenes is 97.238%, indicating an exceptional balance in both detection and association capabilities across varied tracking scenes.

-

LocA (Localization Accuracy): Localization accuracy is assessed independently from other tracking aspects:

$${\rm{LocA}}={\int }_{0}^{1}\frac{1}{\left|{{\rm{TP}}}_{\alpha }\right|}\sum _{c\in \left\{{\rm{TP}}\right\}}{\mathscr{S}}\left(c\right)\,d\alpha ,$$where \({\mathscr{S}}(c)\) represents the spatial similarity score between the predicted detection (prDet) and the ground truth detection (gtDet) that constitute TP c. A score of 82.562% indicates competent localization accuracy, yet highlights the potential for refinement in precise spatial tracking.

-

DetA (Detection Accuracy): This metric evaluates the accuracy with which objects are detected:

$${\rm{DetA}}=\frac{\left|{\rm{TP}}\right|}{\left|{\rm{TP}}\right|+\left|{\rm{FN}}\right|+\left|{\rm{FP}}\right|}.$$Our detection accuracy of 76.030% indicates high performance, capable of delivering reliable results even in complex environments where accurate vehicle detection is essential.

-

AssA (Association Accuracy): This metric measures how accurately object identities are maintained over time such as cars or buses:

$${\rm{AssA}}=\frac{1}{\left|{\rm{TP}}\right|}\sum _{c\in \left\{{\rm{TP}}\right\}}{\mathscr{A}}\left(c\right),$$where \({\mathscr{A}}(c)\) follows the same definition as in Equation (9). With an association accuracy of 81.874%, this metric shows effective identity maintenance, similar to DetA.

-

IDF1 (ID F1 Score): This metric combines ID Precision and ID Recall to evaluate the accuracy of identity assignments across frames. It provides a unified scale to rank all trackers based on a balance between identification precision and recall, calculated through their harmonic mean:

$${{\rm{IDF}}}_{1}=\frac{2\,\,{\rm{IDTP}}}{2\,\,{\rm{IDTP}}+{\rm{IDFP}}+{\rm{IDFN}}},$$where IDTP, IDFP and IDFN carry the similar definitions as in Fig. 27. Our impressive result of 97.404% indicates excellent identity maintenance across various UAV scenes, underscoring the effectiveness of our tracking system.

-

MOTA (Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy): Quantifies overall tracking accuracy by accounting for misses, false positives (e.g., misidentifying a car as a bus), and identity switches, normalized against the total number of ground truth objects:

$${\rm{MOTA}}=1-\frac{\sum \left({\rm{FN}}+{\rm{FP}}+{\rm{IDSW}}\right)}{\sum {\rm{GT}}},$$where GT refers to “gtTraj” as used in HOTA, and IDSW (Identity Switches) denotes the number of times an identity is incorrectly assigned within the tracking sequence. Achieving a MOTA score of 95.474% indicates a high level of overall tracking accuracy.

-

MOTP (Multiple Object Tracking Precision): This metric averages the localization errors of matched detections relative to their respective ground truths:

$${\rm{MOTP}}=\frac{{\sum }_{i\in {\rm{TP}}}{d}_{i}}{\left|{\rm{TP}}\right|},$$where di quantifies the distance between the actual position of the target in frame t and its predicted position. Achieving a MOTP score of 79.846% signifies robust precision in localization accuracy.

-

IDEucl (ID Euclidean Score): This metric assesses a tracker’s efficiency in maintaining consistent identities throughout the length of the gtTraj within the vehicle coordinate space. It calculates the proportion of the trajectory distance over which the correct identity is maintained. Our score of 98.780% indicates that the identities assigned by our tracker align nearly perfectly with the ground truth features.

A visual example explaining the concept of tracking metrics like TP, TPA etc.,this figure is from HOTA77 paper.

Figure 31 illustrates the performance of a UAV vehicle trajectory tracking system across various α thresholds. The graph reveals a noticeable decline in the performance of most metrics as the α value increases, with a sharp drop observed as α approaches 1. This pattern suggests that the system is particularly sensitive to subtle detection or association errors, especially under high threshold conditions. Nonetheless, correlation accuracy metrics, such as AssPr and AssRe, demonstrate high stability even at elevated thresholds, signifying that the tracking system (BotSort) effectively maintains the continuity of vehicle identities.

Performance evaluation of BotSort39 in UAV vehicle trajectory tracking, highlighting the effectiveness of different tracking indicators.

Post-Tracking Data Quality

After evaluating detection and tracking metrics, this section focuses on the quality of post-tracking data. In autonomous driving, ensuring high-quality post-tracking data is crucial, as it directly influences the accuracy of subsequent analyses and the reliability of the system. We specifically focus on two critical issues: the rate of missing data and the inconsistency of labels. Initially, the pixel coordinates obtained from detection and tracking provide the position coordinates of the k-th vehicle at time t as follows:

where label denotes the type of vehicle, either car or bus.

Percentage of Missing Coordinates Post-Tracking

During the tracking process, targets may temporarily or permanently disappear due to occlusion (e.g., trees, surveillance video poles), tracking algorithm failures (e.g., vehicle color similar to the road), or other external factors. Tracking these missing coordinates helps quantify the robustness of tracking algorithms in complex environments. We calculate the data missing rate at seven UAV positions by determining the rate of missed \({P}_{t}^{k}\) for each vehicle as described in Equation (10):

where Lk represents the number of position coordinates obtained by detection and tracking, and Tfin denotes the final timestep value for the k-th vehicle. Results from the seven UAVs over two years are presented in Table 6.

Overall, the average rate over two years is less than 1%, demonstrating our data’s excellent quality and the superiority of algorithms we choose. The lowest rates are recorded by UAV No.6 in 2017 at 0.045% and UAV No.7 in 2018 at 0.068%, both under 0.1%. Conversely, higher rates are observed for UAV No.3 in 2017 (1.211%) and UAV No.1 in 2018 (4.317%), significantly exceeding the average. As illustrated in Fig. 32, challenges in detection and tracking at these sites often stem from suboptimal UAV positioning. For instance, in Fig. 32(a), the UAV captures footage at an oblique angle at a Y-shaped intersection, complicating the detection and tracking process; a similar situation occurs in Fig. 32(b).

Inconsistency in Labels Percentage

In our dataset, maintaining consistent target labels is a vital requirement. Label inconsistencies may stem from identity switching, classification errors, or variations in annotation quality. This section focuses on the “label” dimension as defined in Equation (10), where the label is either car or bus. After completing the missing trajectories using linear interpolation, as described in Equation (1), we calculate the inconsistency rate of labels for the k-th vehicle using the third dimension outlined in Equation (10):

where n* represents the count of each label, such as car or bus. The results across all UAV positions over two years are presented in Table 7.

From 0.143% in 2017 to 0.142% in 2018, the average label inconsistency rate over the two years has not changed significantly. Position 1 (No.1) consistently exhibited a higher rate of label inconsistency than other positions in both years. The UAV images of the 7 positions (Fig. 1) reveal that the tree density at No.1 is significantly higher than at the other positions, which contributes to label confusion.

Usage Notes

Vehicle trajectory prediction is crucial in addressing potential dangers, enhancing planning control, and improving perception capabilities. Current methodologies encompass physics, machine learning, deep learning, and reinforcement learning. Existing datasets often lack extended duration and high-density trajectories; our dataset provides vehicle trajectories up to 130 seconds long. Links to the original videos (number 87) and details on the extracted trajectory information (divided into three parts) are available in the Data Records section.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the pioneers in collecting vehicle trajectory data on a bridge, capturing scenarios such as vehicle entry and exit from the bridge for cars and buses, and station entry and exit for buses.

Our code and dataset comprise the following components:

-

1.

Data Processing: This section of the code explains how to extract vehicle trajectories from UAV-captured videos. It involves two main steps: detection and tracking.

-

Detection: After downloading the YOLO V8 project32, add the detection script located at code/process/1.detect/. To initiate detection, execute the project command using the configuration file:

#!/bin/bash yolo cfg=BridgeCar.yaml # begin detection

The data: field on line 9 of BridgeCar.yaml specifies the path to the images to be detected.

-

Tracking: Include the tracking script code/process/2.BotTrack.py in the YOLO V8 project directory at ultralytics/ultralytics/. Here, the line:

model = YOLO('weights/FinalBest.pt')

refers to the detection parameters trained in the detection step. The source on line 266 specifies the video file to be processed for tracking.

-

2.

Pixel Coordinates: After processing the videos, we extract the original pixel coordinates of vehicle trajectories. The post-processing script code/process/3.post-processed.py addresses missing coordinates, standardizes vehicle labels, and smooths the trajectories. The script inputs are specified by traj_csv_path, which points to the initial vehicle trajectory data obtained from detection and tracking, and track_path, which outputs the final pixel coordinates. The pixel coordinates data comprise two parts: vehicle trajectories and their corresponding lane lines within the same video.

-

3.

Latitude and Longitude Coordinates: The script located at code/PixToL.py converts pixel coordinates to geographic coordinates. The input file path for pixel coordinates is specified by csv_path, and the output path for geographic coordinates is denoted by lon_lat_path. Additionally, cal_path refers to the calibration data used in the conversion process, as detailed in Fig. 17. This process applies to both vehicle trajectories and lane lines, translating them into real-world geographic coordinates.

-

4.

Semantic Promotion: Natural language promotion is achieved using vehicle pixel coordinates, comprising pixel coordinate promotion and vehicle motion classification. Pixel coordinate promotion involves averaging the coordinates from 30 frames per second, performed by the script located at /code/Semantic/Promote.py. This script inputs data from csv_path and outputs results to output_path. Vehicle motion classification is handled by /code/Semantic/Motion.py, demonstrated in Figs. 16 and 18. This script uses the same csv_path and cal_path for inputs, with classifications outputted to output_path.

Code availability

Detection and tracking are performed using YOLOv8 and BoT-SORT, with code publicly available as referenced in the Methods section. Post-processing is conducted in Python, utilizing linear interpolation and mean filtering. Additional tool scripts include:

1. FigTraj.py: Visualizes vehicle trajectories from a CSV file and generates trajectory plots using Matplotlib. The output is saved as No*.png, where * represents the UAV position.

2. PixToL.py: Converts pixel coordinates from vehicle trajectory CSV files into geographic coordinates (latitude/longitude) and saves the results.

3. BridgeCar.yaml: Configuration file for YOLOv8 model training, specifying parameters such as training settings (e.g., epochs, patience, batch size, optimizer) and data augmentation (e.g., scaling, horizontal flipping, translation).

4. root.yaml: Specifies the data root directory and defines vehicle classification indices and names for YOLOv8.

5. Motion.py: Classifies vehicle motion patterns (e.g., lane changes, entering/exiting stations) based on trajectory data and logs the results in a text file.

6. Promote.py: It summarizes vehicle trajectory data by averaging the coordinates every 30 points and logs actions for further analysis.

References

Huang, Y. et al. A survey on trajectory-prediction methods for autonomous driving, IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 652–674, IEEE, (2022).

Kim, B. et al. Lapred: Lane-aware prediction of multi-modal future trajectories of dynamic agents, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 14636–14645, (2021).

Liao, X. et al. Online prediction of lane change with a hierarchical learning-based approach, in 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 948–954, IEEE, (2022).

Mozaffari, S., Al-Jarrah, O. Y., Dianati, M., Jennings, P. & Mouzakitis, A. Deep learning-based vehicle behavior prediction for autonomous driving applications: A review, IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 33–47, IEEE, (2020).

Mo, X., Huang, Z., Xing, Y. & Lv, C. Multi-agent trajectory prediction with heterogeneous edge-enhanced graph attention network, IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 9554–9567, IEEE, (2022).

Liang, M. et al. Fine-Grained Vessel Traffic Flow Prediction with a Spatio-Temporal Multigraph Convolutional Network, IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 23694–23707, IEEE, (2022).

Lin, C.-F., Ulsoy, A. G. & LeBlanc, D. J. Vehicle dynamics and external disturbance estimation for vehicle path prediction, IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 508–518, IEEE, (2000).

Broadhurst, A., Baker, S., Kanade, T. Monte Carlo road safety reasoning, in IEEE Proceedings. Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, pp. 319–324 (2005).

Schulz, J., Hubmann, C., Löchner, J. & Burschka, D. Multiple model unscented kalman filtering in dynamic bayesian networks for intention estimation and trajectory prediction. 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 1467–1474, IEEE, (2018).

Kim, K., Lee, D. & Essa, I. Gaussian process regression flow for analysis of motion trajectories. 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, 1164–1171, IEEE, (2011).

Jiang, Y., Zhu, B., Yang, S., Zhao, J. & Deng, W. Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Considering Driver Uncertainty and Vehicle Dynamics Based on Dynamic Bayesian Network. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, IEEE, (2022)

Ayhan, S. & Samet, H. Aircraft trajectory prediction made easy with predictive analytics. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 21–30 (2016).

Qiu, Z., Ruan, J., Huang, D., Pu, Z. & Shu, S. A prediction method for breakdown voltage of typical air gaps based on electric field features and support vector machine. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation, vol. 22, no. 4, 2125–2135, IEEE, (2015).

Wang, C., Cai, S. & Tan, G. Graphtcn: Spatio-temporal interaction modeling for human trajectory prediction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 3450–3459 (2021).

Ivanovic, B., Leung, K., Schmerling, E. & Pavone, M. Multimodal deep generative models for trajectory prediction: A conditional variational autoencoder approach. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 6, no. 2, 295–302, IEEE, (2022).

Sheng, Z., Xu, Y., Xue, S. & Li, D. Graph-based spatial-temporal convolutional network for vehicle trajectory prediction in autonomous driving. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 23, no. 10, 17654–17665, IEEE, (2022).

Xu, Y., Chakhachiro, T., Kathuria, T. & Ghaffari, M. SoLo T-DIRL: Socially-Aware Dynamic Local Planner based on Trajectory-Ranked Deep Inverse Reinforcement Learning. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 12045–12051, IEEE, (2023).

Alsaleh, R. & Sayed, T. Modeling pedestrian-cyclist interactions in shared space using inverse reinforcement learning. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, vol. 70, 37–57, Elsevier, (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Trajgen: Generating realistic and diverse trajectories with reactive and feasible agent behaviors for autonomous driving. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 23, no. 12, 24474–24487, IEEE, (2022).

Wen, D. et al. Density-Adaptive Model Based on Motif Matrix for Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 14822–14832 (2024).

Li, J., Liu, Y., Zheng, N., Tang, L., Yi, H. Regional coordinated bus priority signal control considering pedestrian and vehicle delays at urban intersections. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 16690–16700, IEEE, (2021).

Gitelman V. & Doveh, E. A comparative evaluation of the safety performance of bus priority route configurations. European Transport Research Review, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 16, Springer, (2023).

Lv, W., Lv, Y., Guo, J., Ma, J. A Lane-Changing Decision-Making Model of Bus Entering considering Bus Priority Based on GRU Neural Network. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. 2022, no. 1, p. 4558946 (2022).

Shelekhov, A. P. et al. Spectra of turbulent fluctuations of Euler angles of unmanned aerial vehicles in the altitude holding mode. 26th International Symposium on Atmospheric and Ocean Optics, Atmospheric Physics, 11560, 1198–1205, SPIE, (2020).

Leal-Taixé, L. et al. Tracking the trackers: an analysis of the state of the art in multiple object tracking. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.02781 (2017).

Voigtlaender, P. et al. Mots: Multi-object tracking and segmentation. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 7942–7951 (2019).

Dendorfer, P. et al. Mot20: A benchmark for multi object tracking in crowded scenes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.09003 (2020).

Li, S., Zhao, S., Cheng, B., Zhao, E. & Chen, J. Robust visual tracking via hierarchical particle filter and ensemble deep features. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 179–191, IEEE, (2018).

Lukežič, A., Zajc, L. Č., Vojíř, T., Matas, J. & Kristan, M. Performance evaluation methodology for long-term single-object tracking. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, vol. 51, no. 12, pp. 6305–6318, IEEE, (2020).

Li, S., Zhao, S., Cheng, B. & Chen, J. Noise-aware framework for robust visual tracking. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 1179–1192, IEEE, (2020).

SOUTH, PHANTOM 4 RTK. available online at http://www.gzsouth.com/prodSerHotProduct/JMAQM9AVYD00BDC5D2KFCRPRB0.

glenn-jocher, ultralytics. GitHub repository https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics, GitHub, (2023).

Jocher, G., Chaurasia, A. & Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8, version 8.0.0. Project https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics, AGPL-3.0, (2023).

Zhu, P. et al. Visdrone-vid2019: The vision meets drone object detection in video challenge results. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, 0–0 (2019).

VisDrone, VisDrone-Dataset. GitHub repository https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset, GitHub, (2018).

Du, D. et al. The unmanned aerial vehicle benchmark: Object detection and tracking. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 370–386 (2018).

Du, D. UAVDT BENCHMARK. Dawei Du’s Homepage https://sites.google.com/view/daweidu/projects/uavdt (2018).

Isell, HumanSignal labelImg. GitHub repository https://github.com/HumanSignal/labelImg, GitHub, (2022).

Aharon, N., Orfaig, R. and Bobrovsky, B.-Z. BoT-SORT: Robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. Project https://arxiv.org/pdf/2206.14651 (2022).

Sun, L., Yang, J. & Mahmassani, H. Travel time estimation based on piecewise truncated quadratic speed trajectory. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 42(1) 173–186, Elsevier, (2008).

Meijering, E. A chronology of interpolation: from ancient astronomy to modern signal and image processing. Proceedings of the IEEE, 90(3), 319–342, IEEE, (2002).

Craven T. & Csordas, G. Multiplier sequences for fields. Illinois Journal of Mathematics, 21(4), 801–817, Duke University Press, (1977).

Wang X. & Liu, S. Vehicle trajectory optimization based on limiting average algorithm. IEEE Access, 9, 9595–9599, IEEE, (2020).

Dinov, I. D., Christou, N. & Sanchez, J. Central limit theorem: New SOCR applet and demonstration activity. Journal of Statistics Education, 16(2), 14, Taylor & Francis, (2008).

Narayanan, S., Moslemi, R., Pittaluga, F., Liu, B. & Chandraker, M. Divide-and-conquer for lane-aware diverse trajectory prediction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 15799–15808 (2021).

Liang, M. et al. Urtasun, Learning lane graph representations for motion forecasting. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 16, 541–556, Springer, (2020).

Gilles, T., Sabatini, S., Tsishkou, D., Stanciulescu, B. & Moutarde, F. Gohome: Graph-oriented heatmap output for future motion estimation. 2022 international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), 9107–9114, IEEE, (2022).

Kim, B. et al. Lapred: Lane-aware prediction of multi-modal future trajectories of dynamic agents. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 14636–14645 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Laformer: Trajectory prediction for autonomous driving with lane-aware scene constraints. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2039–2049 (2024).

Pan, X., Shi, J., Luo, P., Wang, X. & Tang, X. Spatial as deep: Spatial cnn for traffic scene understanding. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 32(1) (2018).

Lee, S. et al. VPGNet: Vanishing Point Guided Network for Lane and Road Marking Detection and Recognition. The IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October (2017).

Guo, Y. et al. Gen-lanenet: A generalized and scalable approach for 3d lane detection. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXI 16, 666–681, Springer, (2020).

Roberts, B. et al. A dataset for lane instance segmentation in urban environments. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 533–549 (2018).

Cheng*, W. et al. DET: A High-resolution DVS Dataset for Lane Extraction. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recog. Workshops (2019).

Xu, H. et al. Curvelane-nas: Unifying lane-sensitive architecture search and adaptive point blending. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XV 16, 689–704, Springer, (2020).

wkentaro, labelme. GitHub repository. Project https://github.com/labelmeai/labelme (2024).

The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, Technical Standards for Highway Engineering Implemented Starting from 2015. Online https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2014-11/20/content_2781017.htm (2014).

Kumar, M. World geodetic system 1984: A modern and accurate global reference frame. Marine Geodesy, 12(2), 117–126, Taylor & Francis, (1988).

Google Earth. Online https://www.google.cn/intl/zh-en/earth/.

Meng, Y., Huang, J., Zhang, Y. & Han, J. Generating training data with language models: Towards zero-shot language understanding. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 462–477 (2022).

Bae, I., Lee, J. & Jeon, H.-G. Can Language Beat Numerical Regression? Language-Based Multimodal Trajectory Prediction. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 753–766 (2024).

Putri, T. D. et al. Intelligent transportation systems (ITS): A systematic review using a Natural Language Processing (NLP) approach. Heliyon, vol. 7, no. 12, Elsevier, (2021).

Prakash, A., Chitta, K. & Geiger, A. Multi-modal fusion transformer for end-to-end autonomous driving, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 7077–7087 (2021).

Bai, S. et al. Connecting language and vision for natural language-based vehicle retrieval, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 4034–4043 (2021).

Kettle, L. & Lee, Y.-C. Augmented reality for vehicle-driver communication: a systematic review. Safety, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 84, MDPI, (2022).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, vol. 1(long and short papers) 4171–4186 (2019).

OpenAI, chatgpt. Online https://chatgpt.com/ (2024).

Xue, H. & Salim, F. D. Promptcast: A new prompt-based learning paradigm for time series forecasting. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, IEEE, (2023).

Cui C. et al. A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, pp. 958–979 (2024).

Su, J. et al. Large language models for forecasting and anomaly detection: A systematic literature review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10350 (2024).

Waymo, Waymo Open Dataset: An autonomous driving dataset. Online: https://www.waymo.com/open (2019).

Wen, D. et al. HDSVT: High-Density Semantic Vehicle Trajectory Dataset Based on a Cosmopolitan City Bridge. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27191856.

Bi, C., Wang, S., Xue, Z., Chen, S. & Huang, Q. Inferential visual question generation. in Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, pp. 4164–4174 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 16965–16974 (2024).

darkpgmr. GitHub repository. Project https://github.com/JonathonLuiten/TrackEval (2021).

davidslater. GitHub repository. Project https://github.com/darkpgmr/DarkLabel (2020).