Abstract

Understanding cortical processing in cochlear implant (CI) users is crucial for improving speech outcomes. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) provides a non-invasive, implant-compatible method for assessing cortical activity during speech comprehension. However, existing studies suffer from methodological heterogeneity and a lack of standardized datasets, limiting cross-study comparisons and generalizability. To address this gap, we present a multimodal fNIRS dataset comprising 46 CI users and 26 normal hearing controls. Participants completed a clinically relevant speech comprehension task using the German Matrix Sentence Test (OLSA) under speech-in-quiet, speech-in-noise, audiovisual and visual speech (i.e., lipreading) conditions. fNIRS recordings covered key cortical regions involved in speech processing, including the prefrontal, temporal, and visual cortices. Additionally, we provide detailed metadata, including patient history, hearing tests, behavioral measures, and spatially registered probe positions. This data descriptor aims to provide a comprehensive resource for investigating multimodal speech understanding in CI users. It enables researchers to explore cortical adaptations in prosthetic hearing, contributing to the refinement of CI rehabilitation strategies and advancing the understanding of auditory neuroplasticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Disabling hearing loss is a leading cause of moderate to severe disability worldwide, affecting over 430 million individuals1. Cochlear implants (CIs) bypass the inner ear and directly stimulate the auditory nerve via electrical potentials, offering a solution to individuals who do not benefit from conventional hearing aids2,3. In terms of speech understanding, despite their proven efficacy, CI outcomes vary significantly due to factors that remain poorly understood4,5,6,7.

Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of brain activation patterns (i.e., cortical factors) in CI outcomes. Investigating these factors under clinically relevant conditions is essential for understanding individual variability, predicting outcomes, and optimizing therapeutic interventions4,5,8,9.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is an ideal neuroimaging tool for investigating cortical activation patterns in CI patients. By measuring changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations (HbO and HbR), fNIRS provides a non-invasive method for assessing cortical hemodynamic activity. It is silent, non-invasive, radiation-free, and compatible with ferromagnetic implants, making it suitable for clinical populations, including patients with CIs. The measuring optical probes, affixed to the head via a cap, enable long-term recordings in diverse environments and are compatible with other imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalography (EEG). fNIRS has been applied across numerous clinical domains, including: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)10, stroke rehabiliation11, depression diagnostics12, neurodegeneration and cognitive decline13,14, hearing loss and speech outcome prediction15,16,17,18, neurorehabiliation19 and tinnitus assessment20,21.

Although fNIRS holds great potential, research on cortical factors in CI patients is complex, and existing studies suffer from methodological heterogeneity and a lack of standardized datasets22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The brain networks supporting speech understanding in CI listeners remain poorly understood, partly due to the challenges of obtaining functional neuroimaging data in this population31.

As a result, the number of available fNIRS datasets in adult CI populations is limited22,23,32. Shader et al. shared a dataset involving 12 newly implanted CI participants, measuring cortical responses above auditory and visual brain areas33,34. Sherafati et al. collected fNIRS data on 20 unilaterally implanted CI patients and normal hearing (NH) controls, focusing on brain regions supporting spoken word understanding31. Steinmetzger et al. shared an fNIRS-EEG dataset of 20 CI patients with single-sided deafness, focusing on voice pitch processing in temporal regions35. Anderson et al. shared a dataset including 17 CI patients and NH controls measured preoperatively in auditory related brain regions30.

These datasets represent important contributions to field30,31,33,34,35. However, they focus on specific aspects of speech processing, thereby do not comprehensively address multimodal speech understanding. In particular, they do not cover all relevant cortical areas involved in audiovisual speech perception31,33. Moreover, these studies lack behavioral assessments during fNIRS acquisition and do not include spatial registration of probe positions30,31,33,34,35.

In our approach, we emphasize the importance of conducting research under clinically relevant conditions. We adapted a clinical speech audiometric test (German Matrix Sentence Test, OLSA), to assess cortical processing under different speech understanding scenarios, including speech-in-quiet, speech-in-noise, audiovisual speech and visual speech (i.e., lipreading) conditions. This approach ensures comparability with clinical assessments and allows for a more comprehensive investigation of multimodal speech understanding. Our dataset covers key brain regions involved in audiovisual speech perception, including the prefrontal, temporal, and visual cortices. We incorporated objective (e.g., hearing tests) and behavioral parameters to improve the accuracy of data interpretation. Further, we conducted spatial registration of the optical probe positions to correct for anatomical differences across participants, improving the reliability of group-level analyses.

The dataset presented in this data descriptor includes 46 CI patients and 26 NH controls. It is valuable for researchers in the field of hearing research, seeking to explore the neural basis of prosthetic hearing rehabilitation with CIs.

Potential applications of this dataset include, but are not limited to (i) exploration of neural mechanisms underlying speech perception in CI users across different listening modalities, (ii) comparative studies between CI and NH individuals to better understand cortical adaptations and neuroplasticity in prosthetic hearing, (iii) correlational analyses linking brain responses with objective or behavioral parameters (e.g., listening effort, speech-in-noise performance), (iv) development and validation of new signal processing pipelines for fNIRS data, especially in clinical populations, (v) training of machine learning models to predict individual rehabilitation outcomes or listening effort from neural signals.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the local ethics committee (KEK-Bern, BASED-ID 2020-02978). All participants provided written informed consent before their participation.

Participants

The dataset comprises 72 participants, including 46 CI users with varying levels of speech understanding and 26 NH controls. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological or psychiatric conditions, nor any brain injury.

As inclusion criteria, CI users met the criterion of pure-tone average (PTA) hearing thresholds exceeding 80 decibel hearing level (dB HL) in both ears, averaged across 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz, confirmed via pure-tone audiometry. During the study, CI users wore the audio processor on their better-hearing side, as determined by audiometric assessment or personal preference.

Study procedure

Each participant took part in a single study appointment, which lasted approximately 2 to 2.5 hours. The study was conducted in a sound-treated acoustic chamber. Participants completed questionnaires, hearing assessments, and performed a multimodal speech comprehension task while brain activity was measured by fNIRS (summarized in Table 1). The score range and interpretation of the collected metadata are summarized in Table 2.

The study procedure involved:

-

Step 1: Initial questionnaires to assess handedness, lipreading experience, and subjective hearing perception.

-

Step 2: Pure-tone and speech audiometry to assess hearing.

-

Step 3 and 5: fNIRS measurements involving multimodal speech comprehension task.

-

Step 4 and 6: Behavioral assessments of listening effort, fatigue, and task engagement.

-

Step 7: Spatial registration of probe positions.

Questionnaires

Before the neuroimaging experiment, participants completed questionnaires on their handedness (Edinburgh Handedness Inventory36), subjective hearing experience (SSQ-1237), and lipreading skills38.

Hearing tests and etiology

All participants underwent speech audiometric testing. Speech recognition in quiet was assessed using the Freiburg monosyllabic word test at 65 dB sound pressure level (SPL), with word recognition scores (WRS) reported as percentages39. Speech recognition in noise was evaluated using the adaptive OLSA40,41,42,43,44, from which the speech reception threshold (SRT) was determined in dB sound-to-noise ratio (SNR). The maximum SNR was limited to 30 dB to avoid loudspeaker distortion.

For CI users, patient history included information on age at onset of deafness, duration of deafness, age at implantation, implant experience and cause of hearing loss. These variables are shared in an aggregated format in order to comply with the legal and ethical guidelines on human subject data.

fNIRS system and data acquisition

We used a continuous-wave fNIRS system (FOIRE-3000, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with 16 light sources and 16 detectors. The system emits laser light at wavelengths of 780 nm, 805 nm, and 830 nm, and a multi-alkali photomultiplier detector captures changes in the light’s intensity.

To account for CI participants, the measurement probes were arranged to allow the attachment of the external CI transmitter behind the ear. The cap design included measurement channels above temporal, visual, and prefrontal brain regions. Three channels were short source-detector separation (SDS) channels to capture extracerebral signals45,46,47. The sampling rate was 14 Hz.

During the fNIRS measurement, participants were seated in a chair behind a desk with a monitor and a loudspeaker. The loudspeaker was calibrated to 65 dB SPL for all stimuli. Following task instructions and familiarization, the fNIRS cap was fitted to the participant’s head. For CI users, any probes interfering with the external transmitter were removed.

fNIRS task design

In fNIRS tasks participants listened to sentences from the clinically established OLSA test48. Each 13-second long stimulus49 consisted of a sentence repeated three times in one of four modalities: (1) speech-in-quiet (fixation cross only), (2) speech-in-noise (fixation cross only), (3) audiovisual speech (without noise), or (4) visual speech (i.e., lipreading). Each block included four stimuli (one per modality) and a comprehension questions about the content. Breaks of 20–25 seconds followed each stimulus, shortened to 10 seconds before comprehension questions, with no time limit for answering (see the block design on Fig. 1).

Overall, participants completed ten counterbalanced blocks, resulting in ten repetitions and two questions per modality. After the fifth block, participants had an extended break to report on behavioral parameters.

Behavioral assessments

We collected behavioral data throughout the experiment to assess task-related parameters, including listening effort according to the Adaptive Categorical Listening Effort Scaling (ACALES)50, fatigue measured using the Rating-of-Fatigue Scale51 and task related attention or mind-wandering52,53.

Spatial registration

Following the fNIRS task, we performed the spatial registration of the optical probe positions on the head using a Structure Sensor Pro 3D scanner (Occipital Inc., Boulder, United States) mounted to an iPad Pro 2020 (Apple Inc., Los Altos, California, United States, iOS 14.3)54.

Data Records

The data are available at Dryad55. The dataset is organized according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure v1.10.0 (BIDS)56 with the extension for NIRS data57.

The main data files are stored in the Shared Near Infrared Spectroscopy Format (SNIRF)58, a widely accepted standard for storing fNIRS data. The SNIRF files contain raw absorbance data from each channel at wavelengths of 780 nm, 805 nm, and 830 nm. They also include probe positions, and associated metadata from questionnaires, hearing tests, behavioral assessments, and patient history.

The temporal structure of each recording is consistent across participants and is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows a representative example from a single participant. The fNIRS task begins with a start trigger, followed by ten counterbalanced blocks, with a break period at halftime.

Example timeline of the complete fNIRS measurement stored in the SNIRF files. The fNIRS task began with a start trigger, followed by ten counterbalanced blocks. These blocks consisted of four different listening conditions and two comprehension questions per condition. The questions had three possible outcomes: Right Answer, Wrong Answer, or Not Sure. After the fifth block, participants had a break, marked with a stop trigger.

Each participant has an individual SNIRF file, and also fields from the BIDS specification. The BIDS fields are replicated from the SNIRF file, which allows relevant behavioral, events or channel related data to be parsed without using an SNIRF reader. The latest specifications of the BIDS-NIRS format can be accessed online59.

Participant-level information is stored in the root directory of the dataset in a “participants.tsv” file, along with an accompanying “participants.json” sidecar that provides descriptions of each column, following BIDS formatting conventions60. These are top level files summarizing relevant demographic and audiometric variables, enabling researchers to filter participant groups efficiently. To complement this, a more detailed Excel file (participants info.xlsx) include all metadata, with accompanying code provided in ”supplementary code” folder in MATLAB61.

For Python, we provide a demonstration pipeline that includes loading, preprocessing, and visualization, implemented in a Jupyter Notebook (ds_main.ipynb) and a supporting script (ds_helpers.py). To run the demonstration, all dependencies listed in the “environment.yml” file needs to be installed.

Technical Validation

The data descriptor includes three main groups of data: (1) metadata, (2) raw fNIRS data, and (3) spatial registration data.

We report the (1) metadata without processing. We share the (2) raw fNIRS data in a BIDS-compliant format, and additionally we provide scripts for processing and visualization. We processed and visualized the (3) spatial registration data according to Bálint et al.54.

fNIRS data processing

We used the MNE-NIRS toolbox for fNIRS data processing62,63. In the first step, we conducted short-separation regression on the raw absorbance data using the nearest short SDS channel46,64,65. The signal was then bandpass filtered in the range of 0.01-0.1 Hz66.

Following, we converted to changes in HbO and HbR concentrations according to the specifications of the fNIRS machine (resulting unit µMolar*cm67):

Motion artifacts were removed using temporal derivative distribution repair (TDDR)68.

Individual epochs from 0 to 24 seconds following the onset of stimulation were extracted and baseline corrected (−5 to 0 seconds). Epochs in which participants reported interference (e.g., movement during stimulus presentation, incorrectly selected answers) were removed, which affected 0.29% of all epochs. In addition, due to physical constraints from the CI coil, and cap setup, a subset of channels (4.5% of all channels) were marked as NaNs, meaning they were not used in the analysis.

Spatial registration processing

On the 3D scans, we manually labeled the probe positions and anatomical landmarks (nasion, left and right preauricular points) using MeshLab (version 2022.02)69. These labeled probe positions were then aligned with the MNE-Python 10-05 template62,63 through rigid registration, using the anatomical landmarks as control points54. The resulting 3D positions are provided in the coordinate system of the MNE 10-05 template. In 14 NH and 9 CI cases out of 72 participants the spatial registration was insufficient, and data from a comparable participant with a matching head circumference was used. On average, a matching head size could be found within an error of 0.39 cm (standard deviation = 0.30 cm, range = 0-1.25 cm). These participants are marked in the dataset with the variable “HeadSizeMatch”.

Metadata results

Figure 3 shows two examples from the metadata. The top row shows the distribution of participants based on their SRT. For NH participants, the values are consistent with normative data70. Some CI participants had an SRT comparable to those of the NH group, while others performed above this level (which means worse speech understanding in noise).

Example variables from the audiological and behavioral assessments between normal hearing (controls, NH) and cochlear implant (CI) participants: The top row is the participant distribution by speech reception threshold (SRT), and the bottom row is the reported listening effort based on the Adaptive Categorical Listening Effort Scaling (ACALES). The box plot shows the median, quartiles, data range, and any outliers.

The bottom row shows listening effort ratings across different conditions during the fNIRS speech comprehension task. As expected due to their lower speech understanding, CI participants reported higher listening effort in speech-in-quiet, speech-in-noise, and audiovisual conditions compared to NH participants (top row). In the visual speech (i.e., lipreading) condition, CI participants showed effort across a wide range, with a trend towards reporting lower effort compared to NH participants.

fNIRS data results

The neurophysiological basis of fNIRS lies in the detection of local hemodynamic responses which reflects neural activity. In an activated brain region the blood flow increases more than oxygen metabolism, leading to changes in hemoglobin concentration71. Typically, an increase in HbO and a corresponding decrease in HbR concentration indicate a canonical hemodynamic response. The fNIRS signal is inherently slow, peaking multiple seconds after stimulation72.

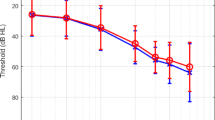

Figure 4 shows grand average evoked hemodynamic responses for three selected regions of interest (ROIs) across conditions in the NH group. Distinct activation patterns were observed: speech-in-quiet and speech-in-noise activated bilateral temporal ROIs, visual speech stimuli engaged mainly the occipital ROI, and audiovisual stimuli activated all ROIs. Channel positions contributing to each ROI are shown in the top right corner .

Grand average evoked responses in three selected regions of interest (ROIs) for each condition. The red signal represents the concentration change in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and the blue signal in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR). Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The signals are measured in the normal hearing (NH) participants, who are serving as controls. In the top right corner, we show the channel positions which were included in the corresponding ROI, indicating the brain regions contributing to the grand average patterns. An increase in HbO and a decrease in HbR concentration indicate typical hemodynamic responses.

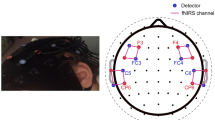

Spatial registration results

We have visualized the registered probe positions on Fig. 5, showing lateral, caudal and medial views. The yellow dots represent all of the registered positions. The red dots represent the light sources, while the blue dots represent the light detectors for a single participant. The cap design ensured coverage of key audiovisual speech regions, including the occipital cortex, left and right temporal cortices, and prefrontal areas.

Code availability

The code is available at Dryad55.

References

Organization, W. H. et al. World report on hearing. World Health Organization (2021).

Bond, M. et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cochlear implants for severe to profound deafness in children and adults: a systematic review and economic model. Health technology assessment 13(44), 1–196 (2009).

Carlson, M. L. Cochlear implantation in adults. New England Journal of Medicine 382(16), 1531–1542 (2020).

Lazard, D. S. et al. Pre-, per-and postoperative factors affecting performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: a new conceptual model over time. PloS one 7(11), 48739 (2012).

Blamey, P. et al. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients. Audiology and Neurotology 18(1), 36–47 (2012).

Kral, A., Aplin, F. & Maier, H. Prostheses for the Brain: Introduction to Neuroprosthetics. Academic Press (2021).

Bálint, A., Wimmer, W., Caversaccio, M., Rummel, C. & Weder, S. Linking brain activation to clinical outcomes: An fnirs study in cochlear implant users and normal hearing individuals. (Neurophotonics) (2025).

McKay, C. M. Brain plasticity and rehabilitation with a cochlear implant. Advances in Hearing Rehabilitation 81, 57–65 (2018).

Lawrence, R. J., Wiggins, I. M., Anderson, C. A., Davies-Thompson, J. & Hartley, D. E. Cortical correlates of speech intelligibility measured using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fnirs). Hearing research 370, 53–64 (2018).

Poliakova, E., Conrad, A. L., Schieltz, K. M. & O’Brien, M. J. Using fnirs to evaluate adhd medication effects on neuronal activity: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in neuroimaging 2, 1083036 (2023).

Huo, C. et al. A review on functional near-infrared spectroscopy and application in stroke rehabilitation. Medicine in Novel Technology and Devices 11, 100064 (2021).

Ho, C. S. et al. Diagnostic and predictive applications of functional near-infrared spectroscopy for major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Frontiers in psychiatry 11, 378 (2020).

Yang, D., Hong, K.-S., Yoo, S.-H. & Kim, C.-S. Evaluation of neural degeneration biomarkers in the prefrontal cortex for early identification of patients with mild cognitive impairment: an fnirs study. Frontiers in human neuroscience 13, 317 (2019).

Pinti, P. et al. The present and future use of functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fnirs) for cognitive neuroscience. Annals of the new York Academy of Sciences 1464(1), 5–29 (2020).

Bálint, A., Wimmer, W., Rummel, C., Caversaccio, M. & Weder, S.: Neural correlates of speech comprehension in normal hearing individuals and cochlear implant users-an fnirs study in quiet and noisy environments. In: 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), pp. 1–5 IEEE (2024).

Weder, S., Zhou, X., Shoushtarian, M., Innes-Brown, H. & McKay, C. Cortical processing related to intensity of a modulated noise stimulus—a functional near-infrared study. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 19(3), 273–286 (2018).

Weder, S. et al. Cortical fnirs responses can be better explained by loudness percept than sound intensity. Ear and hearing 41(5), 1187–1195 (2020).

Bálint, A. et al. Neural activity during audiovisual speech processing: Protocol for a functional neuroimaging study. JMIR research protocols 11(6), 38407 (2022).

Mihara, M. & Miyai, I. Review of functional near-infrared spectroscopy in neurorehabilitation. Neurophotonics 3(3), 031414 (2016).

Shoushtarian, M. et al. Objective measurement of tinnitus using functional near-infrared spectroscopy and machine learning. PLoS One 15(11), 0241695 (2020).

Shoushtarian, M., Esmaelpoor, J., Bravo, M. M. & Fallon, J. B. Cochlear implant induced changes in cortical networks associated with tinnitus severity. Journal of Neural Engineering 21(5), 056009 (2024).

Harrison, S. C., Lawrence, R., Hoare, D. J., Wiggins, I. M. & Hartley, D. E. Use of functional near-infrared spectroscopy to predict and measure cochlear implant outcomes: A scoping review. Brain Sciences 11(11), 1439 (2021).

Farrar, R., Ashjaei, S. & Arjmandi, M. K. Speech-evoked cortical activities and speech recognition in adult cochlear implant listeners: a review of functional near-infrared spectroscopy studies. Experimental Brain Research 242(11), 2509–2530 (2024).

Chen, L.-C., Stropahl, M., Schönwiesner, M. & Debener, S. Enhanced visual adaptation in cochlear implant users revealed by concurrent eeg-fnirs. Neuroimage 146, 600–608 (2017).

Chen, L.-C., Sandmann, P., Thorne, J. D., Herrmann, C. S. & Debener, S. Association of concurrent fnirs and eeg signatures in response to auditory and visual stimuli. Brain Topography 28, 710–725 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Cortical speech processing in postlingually deaf adult cochlear implant users, as revealed by functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Trends in hearing 22, 2331216518786850 (2018).

Olds, C. et al. Cortical activation patterns correlate with speech understanding after cochlear implantation. Ear and hearing 37(3), 160–172 (2016).

Fullerton, A. M. et al. Cross-modal functional connectivity supports speech understanding in cochlear implant users. Cerebral Cortex (2022).

Anderson, C. A., Lazard, D. S. & Hartley, D. E. Plasticity in bilateral superior temporal cortex: Effects of deafness and cochlear implantation on auditory and visual speech processing. Hearing research 343, 138–149 (2017).

Anderson, C. A., Wiggins, I. M., Kitterick, P. T. & Hartley, D. E. Pre-operative brain imaging using functional near-infrared spectroscopy helps predict cochlear implant outcome in deaf adults. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 20(5), 511–528 (2019).

Sherafati, A. et al. Prefrontal cortex supports speech perception in listeners with cochlear implants. elife 11, 75323 (2022).

Gomes, L. F., Vasconcelos, I. C. D., Taveira, K. V. M., Balen, S. A. & Brazorotto, J. S. Functional near-infrared spectrometry for auditory speech stimuli in cochlear implant users: a systematic literature review. Cochlear Implants International 25(6), 445–458 (2024).

Shader, M. J., Luke, R. & McKay, C. M.: Contralateral dominance to speech in the adult auditory cortex immediately after cochlear implantation. Iscience 25(8) (2022).

Shader, M. J. & Luke, R.: Auditory- and visual-evoked activity in newly implanted adult CI recipients. Mendeley Data https://doi.org/10.17632/377b4ff8p6. 1 (2022).

Steinmetzger, K., Meinhardt, B., Praetorius, M., Andermann, M. & Rupp, A. A direct comparison of voice pitch processing in acoustic and electric hearing. NeuroImage: Clinical 36, 103188 (2022).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9(1), 97–113 (1971).

Noble, W., Jensen, N. S., Naylor, G., Bhullar, N. & Akeroyd, M. A. A short form of the speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale suitable for clinical use: The ssq12. International journal of audiology 52(6), 409–412 (2013).

Bálint, A., Wimmer, W., Caversaccio, M., Rummel, C. & Weder, S. Brain activation patterns in normal hearing adults: An fnirs study using an adapted clinical speech comprehension task. Hearing Research 455, 109155 (2025).

Hahlbrock, K.-H. Sprachaudiometrie: Grundlagen und Praktische Anwendung Einer Sprachaudiometrie Für Das Deutsche Sprachgebiet; 157 Abbildungen in 305 Einzeldarstellungen 9 Tabellen. Thieme,??? (1970).

Wagener, K., Brand, T. & Kollmeier, B. Development and evaluation of a german sentence test part iii: Evaluation of the oldenburg sentence test. Zeitschrift Fur Audiologie 38, 86–95 (1999).

Wagener, K., Hochmuth, S., Ahrlich, M., Zokoll, M. & Kollmeier, B.: Der weibliche oldenburger satztest. In: 17th Annual Conference of the DGA, Oldenburg, CDRom (2014).

Wimmer, W., Kompis, M., Stieger, C., Caversaccio, M. & Weder, S. Directional microphone contralateral routing of signals in cochlear implant users: A within-subjects comparison. Ear and hearing 38(3), 368–373 (2017).

Gawliczek, T. et al. Unilateral and bilateral audiological benefit with an adhesively attached, noninvasive bone conduction hearing system. Otology & neurotology 39(8), 1025–1030 (2018).

Wardenga, N. et al. Do you hear the noise? the german matrix sentence test with a fixed noise level in subjects with normal hearing and hearing impairment. International journal of audiology 54(sup2), 71–79 (2015).

Scholkmann, F., Tachtsidis, I., Wolf, M. & Wolf, U. Systemic physiology augmented functional near-infrared spectroscopy: a powerful approach to study the embodied human brain. Neurophotonics 9(3), 030801–030801 (2022).

Wyser, D. et al. Short-channel regression in functional near-infrared spectroscopy is more effective when considering heterogeneous scalp hemodynamics. Neurophotonics 7(3), 035011 (2020).

Wyser, D. G. et al. Characterizing reproducibility of cerebral hemodynamic responses when applying short-channel regression in functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Neurophotonics 9(1), 015004 (2022).

Llorach, G. et al. Development and evaluation of video recordings for the olsa matrix sentence test. International Journal of Audiology 61(4), 311–321 (2022).

Zhang, Y. F., Lasfargues-Delannoy, A. & Berry, I. Adaptation of stimulation duration to enhance auditory response in fnirs block design. Hearing Research 424, 108593 (2022).

Krueger, M. et al. Relation between listening effort and speech intelligibility in noise. American Journal of Audiology 26(3S), 378–392 (2017).

Micklewright, D., St Clair Gibson, A., Gladwell, V. & Al Salman, A. Development and validity of the rating-of-fatigue scale. Sports Medicine 47(11), 2375–2393 (2017).

Unsworth, N. & McMillan, B. D. Similarities and differences between mind-wandering and external distraction: A latent variable analysis of lapses of attention and their relation to cognitive abilities. Acta psychologica 150, 14–25 (2014).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maj, M., Linden, M. & D’Argembeau, A. Mind-wandering: Phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta psychologica 136(3), 370–381 (2011).

Bálint, A., Rummel, C., Caversaccio, M. & Weder, S. Three-dimensional infrared scanning: an enhanced approach for spatial registration of probes for neuroimaging. Neurophotonics 11(2), 024309 (2024).

Bálint, A., Wimmer, W., Rummel, C., Caversaccio, M., Weder, S. An fNIRS Dataset for Multimodal Speech Comprehension in Normal Hearing Individuals and Cochlear Implant Users, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.crjdfn3g9.

Gorgolewski, K. J. et al. The brain imaging data structure, a format for organizing and describing outputs of neuroimaging experiments. Scientific data 3(1), 1–9 (2016).

Luke, R. et al. Nirs-bids: Brain imaging data structure extended to near-infrared spectroscopy. Scientific Data 12(1), 159 (2025).

Tucker, S. et al. Introduction to the shared near infrared spectroscopy format. Neurophotonics 10(1), 013507 (2023).

Brain Imaging Data Structure Specifications for NIRS. https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/en/stable/modality-specific-files/near-infrared-spectroscopy.html. Accessed: 2025-01-31.

Brain Imaging Data Structure Specifications for Modality agnostic files. https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/en/stable/modality-agnostic-files.html. Accessed: 2025-06-18.

Santosa, H., Zhai, X., Fishburn, F. & Huppert, T. The nirs brain analyzir toolbox. Algorithms 11(5), 73 (2018).

Gramfort, A. et al. Mne software for processing meg and eeg data. Neuroimage 86, 446–460 (2014).

Luke, R. et al. Analysis methods for measuring passive auditory fnirs responses generated by a block-design paradigm. Neurophotonics 8(2), 025008–025008 (2021).

Scholkmann, F. et al. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. Neuroimage 85, 6–27 (2014).

Saager, R. B. & Berger, A. J. Direct characterization and removal of interfering absorption trends in two-layer turbid media. JOSA A 22(9), 1874–1882 (2005).

Cai, Z. et al. Evaluation of a personalized functional near infrared optical tomography workflow using maximum entropy on the mean. Human Brain Mapping 42(15), 4823–4843 (2021).

Baker, W. B. et al. Modified beer-lambert law for blood flow. Biomedical optics express 5(11), 4053–4075 (2014).

Fishburn, F. A., Ludlum, R. S., Vaidya, C. J. & Medvedev, A. V. Temporal derivative distribution repair (tddr): a motion correction method for fnirs. Neuroimage 184, 171–179 (2019).

Cignoni, P. et al. Meshlab: an open-source mesh processing tool. In: Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference, vol. 2008, pp. 129–136 (2008). Salerno, Italy

Schmid, C., Wimmer, W. & Kompis, M. Bpace: A bayesian, patient-centered procedure for matrix speech tests in noise. Trends in hearing 27, 23312165231191382 (2023).

Handwerker, D. A., Ollinger, J. M. & D’Esposito, M. Variation of bold hemodynamic responses across subjects and brain regions and their effects on statistical analyses. Neuroimage 21(4), 1639–1651 (2004).

Polimeni, J. R. & Lewis, L. D. Imaging faster neural dynamics with fast fmri: A need for updated models of the hemodynamic response. Progress in neurobiology 207, 102174 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Wonderland Foundation, the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation, and the UniBern Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft. W.W.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis. C.R.: methodology, formal analysis. M.C.: supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. S.W.: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition, writing-original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bálint, A., Wimmer, W., Rummel, C. et al. An fNIRS dataset for Multimodal Speech Comprehension in Normal Hearing Individuals and Cochlear Implant Users. Sci Data 12, 1305 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05654-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05654-w