Abstract

Diabetes is a major health challenge that affects millions of people worldwide. Managing diabetes effectively requires monitoring blood glucose levels continuously, typically through invasive sensing devices such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs). Blood glucose excursions have been shown to induce changes in several physiological signals such as electrocardiography (ECG), photoplethysmography (PPG) and electrodermal activity (EDA) that can be measured non-invasively with consumer-grade wearable sensors. These physiological changes can be mapped into glucose levels using machine-learning models trained on comprehensive multimodal datasets of physiological signals. However, most existing datasets lack ground-truth measurements from CGMs and often only include aggregated physiological data (e.g. heart rate) at low sampling rates. To address these gaps, we introduce PhysioCGM, an open-source dataset that contains raw physiological recordings from multiple sensors including ECG, PPG, EDA, skin temperature, accelerometry and ground-truth CGM data collected for up to 17 days from 10 participants with Type 1 Diabetes in ambulatory settings. This dataset aims to promote the development of non-invasive methods for glucose monitoring and improve diabetes management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Diabetes affects over 38 million people in the United States and is the eighth leading cause of death, with over $400 billion (about $1,200 per person in the US) in direct medical costs incurred in 2022 alone1. Furthermore, approximately 1.2 million new cases of diabetes are diagnosed each year, which amounts to one American being diagnosed with diabetes every 30 seconds. The most common condition (~90% of all cases) is Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), a metabolic disease commonly associated with lifestyle factors (diet, physical inactivity), which can reduce the body’s ability to absorb glucose (insulin resistance). The other condition (~10% of all cases) is Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), an autoimmune disease often diagnosed in childhood or adolescence that destroys beta-cells in the pancreas, which are responsible for producing insulin. Regardless of the condition, elevated blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia) can lead to serious long-term complications, including heart disease, kidney failure, blindness, amputation, and stroke2,3. Conversely, low glucose levels (hypoglycemia) can be life-threating in the short-term, as it leads to confusion, irritability, impaired attention and coma if left untreated4.

Thus, effective management of diabetes relies heavily on carefully monitoring and maintaining blood glucose levels. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) can be used for this purpose, but they are invasive and can be costly since sensors must be replaced every 7–14 days. Non-invasive sensing alternatives, such as electrocardiography (ECG) and photoplethysmography (PPG), have been shown to correlate with glucose levels5. Specifically, changes in cardiac signals, such as a lengthened QT interval and reduced heart rate variability (HRV), have long been known to be associated with hypoglycemia6,7. Additionally, studies have shown that sensor fusion of multiple physiological signals can improve predictive accuracy8,9. Key to the development of these data-driven approaches is access to multimodal datasets to train machine-learning (ML) models.

Various datasets have been proposed to advance research in non-invasive glucose estimation, as summarized in Table 1. The MIMIC II dataset10 available on PhysioNet (https://physionet.org/) contains comprehensive clinical and waveform data from intensive care unit (ICU) patients, recorded with medical-grade devices in stationary conditions. While this dataset offers high-quality signals, it is not representative of everyday data collected from wearable devices, and glucose levels were only recorded as needed for patient care. PhysioNet hosts numerous physiological databases, such as the MIT-NIH arrhythmia dataset11, which provides ambulatory ECG data, but none include continuous glucose level time series. The UC Irvine Machine Learning Repository (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/) also contains related datasets, including the MHEALTH dataset12, containing physical activity and 2-lead ECG recordings, and the Diabetes dataset13 containing manual measurements of pre- and post-prandial glucose with limited meal information. However, these datasets either lack ground-truth glucose measurements to evaluate glucose estimation or they do not include synchronized ECG data. The Diabetic Cardiac Neuropathy Diagnostic and Modeling (DICARDIA) dataset14 offers ECG data from patients with diabetes, with one measurement of glucose and HbA1c per patient, so it cannot be used to provide continuous estimates of glucose from ECG. The OhioT1DM dataset15 includes eight weeks of continuous glucose monitoring, insulin dosing data, physiological recordings (accelerometry and skin conductance), and self-reported life events for 12 individuals with T1D. However, the dataset lacks data from other physiological sensors such as ECG or PPG. To our knowledge, the only publicly available dataset containing both ECG and CGM recordings is D1NAMO dataset16. The D1NAMO dataset includes other relevant data such as accelerometry recordings for activity recognition and annotated food images for 20 healthy and 9 participants with T1D. However, this dataset lacks PPG and EDA information and only contains data for up to four days per participant. Other studies requiring data from multiple modalities such as ECG, PPG, skin conductance and glucose data have been conducted, but such datasets are not publicly available8,17.

To address this gap, we present PhysioCGM, an open-source dataset that integrates information from three wearable physiological sensors: (1) a Zephyr Bioharness18 chest strap that records raw ECG and respiratory signals, (2) an Empatica E419 watch that records raw PPG and EDA, and (3) a Dexcom G6 CGM that records interstitial glucose. Currently, our PhysioCGM dataset contains recordings of 10 participants with T1D who wore the three sensing devices in ambulatory settings for up to 17 days. This unique dataset provides continuous, multi-modal physiological data that can be used to develop models that predict glycemic excursions and related complications. PhysioCGM aims to facilitate the development of innovative, non-invasive monitoring solutions that improve the quality of life for individuals with diabetes.

Methods

The dataset was collected at Baylor College of Medicine under IRB protocol H-49867. Participants were eligible to participate in the study if they had a clinical diagnosis of T1D with a duration greater than 1 year and were 13 years or older. All participants were verified to have ≥80% CGM use in the month before enrollment. Participants consented to having their demographic information and deidentified sensor data released. Ten subjects were enrolled between ages 29–41 years and Body Mass Index (BMI) in the range 21.8–34.1 kg/m2. Participant demographics are included in Table 2. All participants were recruited between 2021 and 2022. During the study period, participants were equipped with two non-invasive devices: a Zephyr Bioharness and an Empatica E4 watch. In addition, participants wore a Dexcom G6 CGM and an insulin pump as part of their standard diabetes management routine. The Zephyr Bioharness20 is worn just below the chest and measures ECG at 250 Hz, thoracic expansion at 25 Hz, accelerometry at 100 Hz (3-axis), heart rate (HR) at 1 Hz and HR confidence (HRC) at 1 Hz. The Empatica E419 is worn on the wrist and captures PPG at 64 Hz and EDA at 4 Hz. The Dexcom G6 CGM sensor is attached to the skin over the arm and provides subcutaneous glucose reading every 5 minutes (0.0033 Hz).

Participants were trained in-person by the clinical team on how to wear and charge the devices and were provided with a user manual and a Windows laptop. They were instructed to wear the devices continuously throughout the study, encompassing both day and night periods, except during times allocated for charging them each day, typically prior to bedtime. While the devices were being charged, participants uploaded raw sensor data from the previous 24 hours to cloud services using the laptop. Participants uploaded raw sensor data from the E4 watch to Empatica’s cloud service using an Empatica PC application (E4 Manager). Participants downloaded raw sensor data from the BioHarness to a local drive on the laptop using a Zephyr PC application (Zephyr Downloader) and then uploaded the data to a Google Drive set up by the engineering team. Whenever the engineering team identified missing data or data quality issues, participants were contacted by the clinical team to troubleshoot the process and/or adjust how the devices were worn. CGM data from each patient was downloaded to Google Drive by the clinical team. The PhysioCGM dataset includes human-readable raw sensor data without any preprocessing/curation steps, as well as pkl binary files for ease of use; please refer to Data Records. There was variability in the available data across the 24-hour window for each participant –see Table 2. This indicates that participants may have removed their devices during activities such as showering or other circumstances where device removal was necessary.

Data Records

All data records in the dataset are included in this submission and are accessible via FigShare21. Table 3 and Fig. 1 provides a detailed overview of these records and the hierarchical structure of the dataset. The dataset is organized into two cohort folders, each containing data from five participants. Each subject is identified by a de-identified code, e.g. c1s02 represents the second subject from cohort 1. Within each subject’s folder, there are three subfolders: zephyr, e4, and CGM, each storing the data from respective sensors. The zephyr folder contains session folders of recordings, with each session folder including seven CSV files that capture various data types, including ECG, acceleration, and breathing waveforms. The e4 folder stores data from the Empatica E4 watch, including PPG, EDA and accelerometry. Lastly, the CGM folder contains a file that stores glucose values. Each data record includes a time-stamp field, which allows time alignment of signals from different sensors.

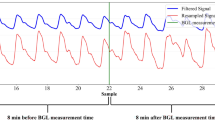

To streamline data access and training, we preprocess the raw data records from all sensors and align them based on their corresponding timestamps. They are then split at the CGM level and packed into pkl binary files for ease of use. The processed data is organized by subjects. Within each subject’s folder, there are multiple subfolders corresponding to different days, each of which contain multiple pkl files. Each pkl file contains 5-minute signal clips and metadata that are synchronized with CGM timestamps. A detailed schema outlining this structure is included as a readme file on figshare. Figure 2 shows an example of the signals contained within each pkl file.

Technical Validation

To establish the validity of the dataset, we report an analysis of CGM recordings, signal quality for each sensing modality and results on hypoglycemia predictions from individual sensors and joint models that combine predictions from multiple sensors.

CGM readings

For each patient in the dataset, we divided CGM data into five clinically relevant categories22: very low (<54 mg/dL), low (54–69 mg/dL), target range (70–180 mg/dL), high (181–250 mg/dL), and very high (>250 mg/dL); see Fig. 3. These results indicate that blood glucose for all patients meet the clinical target of maintaining blood glucose within the target range of 70–180 mg/dL for more than 70% of the time23. Additionally, Fig. 4 presents the hourly average of glucose levels from the CGM throughout the collection days for all subjects. White cells indicate time blocks with missing CGM recordings, likely due to loss of connectivity between the CGM device and the patient’s smartphone.

Average hourly blood glucose reading for each subject in the PhysioCGM dataset21.

Physiological signal quality

To validate the physiological recordings, we analyzed the signal quality for ECG, PPG and EDA. In a first step, we examined the average number of “clean” ECG beats, as defined by the HR confidence (HRC; the percentage for level of confidence the BioHarness device is able to detect heart rate during activity) and ECG noise (ECG-N) diagnostic values in the Bioharness recording, as described in the manufacturer’s Log Data Descriptions20. Specifically, we considered a beat to be “clean” if the corresponding HRC = 100 and ECG-N < 0.001. To segment heart beats from the raw ECG signal, we used the Neurokit library24 to extract the R-peak in the QRS complex. Then, we extracted an analysis window as a function of the R-R period (inverse of the instantaneous heart rate), keeping RR/3 samples prior to the R-peak and RR/2 samples after the R-peak. Figure 5 shows the number of clean ECG beats at 15-min intervals for one data collection day for participant c2s02, along with the vector magnitude unit (VMU) of the BioHarness accelerometer. The figure shows a large difference in the number of clean ECG beats between daytime (approximately 90%) and nighttime (40%). This difference is likely attributed to the effect of motion artifacts, which increase as the participant performed activities of daily living.

We also analyzed 17-day PPG recordings from one of the participants and computed the skewness of the signal. The skew is a measure of the symmetry (or lack of it) of the distribution of the data. Figure 6b shows a heatmap of the skewness, a signal quality index (SQI) commonly used25, with each column representing a 15-min period (from midnight to midnight), averaged across the 17 study days. In turn, each row in the heatmap represents the number of 30-sec analysis windows with a given skewness value. Notice that nocturnal skewness hovers in the range [−0.6, −0.8], indicative of high SQI. In contrast, the diurnal skewness is distributed over a broader range, indicating poor quality –as we would expect due to motion artifacts. Figure 6c shows the number of 30-sec analysis windows over the 24-hour period with high SQI (skewness in the range [−0.6, −0.8]). Though the number of windows with high SQI is significantly larger at night, approximately 100 analysis windows with high SQI are available during the day, thus still allowing prediction of glycemic excursions at any time in a 24-hour period26.

(a) Examples of PPG signals considered Excellent, Acceptable and Unfit for diagnosis; adapted from25 (b) Distribution of skewness over a 24-hour period for PPG signals recorded over a 17-day period. (c) Average number of analysis windows per 15-minute interval with skewness in the range [−0.6, −0.8].

Finally, to assess the quality of EDA recordings, we implemented an automated assessment methodology as originally described by27, with adjustments to accommodate differences in our dataset, mainly the sampling rate of the EDA recordings on the Empatica E4 (4 Hz). The original procedure27 used a low-pass finite impulse response (FIR) “de-spiking” filter with a cutoff of 0.35 Hz (sampling rate: 32 Hz) to remove noise while preserving low-frequency changes associated with skin conductance level (SCL) and skin conductance responses (SCRs). It applied four rules for data validity: (1) EDA range between 0.05–60 μS, (2) maximum slope of ±10 μS/sec, (3) temperature range of 30–40 °C, and (4) surrounding invalid data transitions. This approach showed excellent sensitivity (91%) and specificity (99%) when tested against expert-annotated EDA data. We adjusted the FIR filter cutoff frequency proportionally to 0.04 Hz to reflect the lower Nyquist frequency and scaled the slope threshold to ±2.5 μS/sample. Transition effects were recalibrated to 20 samples surrounding invalid data points (equivalent to 5 seconds). The EDA range check was modified to a maximum value of 100 μS, the largest value reported by the Empatica E4. We retained the remaining rules, including temperature range checks, as originally described by Kleckner et al.27.

Figure 7 shows the percentage of valid EDA data points in 5-minute intervals across a 24-hour period, averaged over 17 days for subject c2s02. During the night until early morning, the percentage of valid data points remains consistent and approaches or exceeds 95%. This trend likely reflects minimal movement and physiological changes during sleep or reduced physical activity, which reduce artifacts such as abrupt EDA fluctuations or temperature variability. In contrast, significant drops in data validity occur between 10:00 and 14:00, with values dipping below 70% in some intervals. These declines may coincide with periods of increased physical activity or transitions, such as meals, tasks, or environmental changes, which introduce noise or cause data to fall outside predefined validity thresholds like rapid slope changes or extreme values. A noticeable decline is observed again in the late evening hours, around 20:00, though validity largely remains above 80%.

Percentage of valid EDA data points across a 24-hour period, averaged in 5-minute intervals over 17 days for subject c2s02. Data validity is highest during early morning hours and late afternoon, coinciding with periods of reduced activity. Significant drops in validity are observed during midday (10:00–14:00) and late evening, likely due to increased movement or environmental transitions introducing artifacts.

Hypoglycemia detection from physiological signals

In a final analysis, we illustrate the potential use of PhysioCGM for detecting hypoglycemia non-invasively. Hypoglycemia is a critical challenge for individuals with diabetes and needs timely detection because the symptoms are hard to notice and can impact various bodily functions28. Traditional methods typically rely on CGM or ECG data alone17,29, but integrating additional physiological signals has been shown to enhance prediction accuracy8,9. We explore the use of multiple sensors—ECG, PPG, and EDA— to predict hypoglycemia individually and in combination.

We used CGM data as ground truth and classified CGM segments with glucose levels below 70 mg/dL as hypoglycemic, and glucose levels at or above 70 mg/dL as euglycemic. We used a hierarchical approach to integrate information from each modality at different levels of granularity. ECG signals were analyzed using 3-second windows centered around R-peaks, capturing morphological changes and heart rate information. PPG signals were segmented into 30-second intervals, providing a balance between capturing temporal changes and mitigating noise. Finally, EDA signals were analyzed over 5-minute windows to integrate macro-level patterns of autonomic arousal that may be indicative of hypoglycemic episodes. The data preprocessing steps, model design and results are detailed below.

Data preprocessing

ECG signals

We used a fixed 3-second window centered around the R-peak (see Physiological signal quality), as ECG signals are generally cleaner for extracting individual beats. This approach avoids relying on the RR-interval and instead ensures consistent data length while capturing both the morphology of the ECG waveform and instantaneous HR (i.e., distance between R-peaks). Typically, a 3-second window contains two to three R-peaks, depending on heart rate. To maintain quality, we only included clean ECG beats, i.e., HRC = 100 and ECG-N < 0.001, as described in Physiological signal quality.

PPG signals

We extracted 30-second intervals with a stride of 50% to ensure sufficient overlap between consecutive windows. A longer window is preferred for PPG to mitigate the impact of motion artifacts, which can compromise beat-level robustness. This window length enables the model to capture temporal trends more effectively without requiring explicit beat extraction. Additionally, we preprocess the raw PPG signal using the ‘ppg_clean’ function from NeuroKit2, which implements the method described in Elgendi et al.25 This method applies a second-order Butterworth bandpass filter (0.5–8 Hz) to remove baseline wander and high-frequency noise while preserving the physiological morphology of the PPG waveform.

EDA Signals

We process EDA signals using a 5-minute window, which matches the CGM sampling period. This macro-level analysis captures broader autonomic arousal patterns over time. For segments where the EDA data does not span the full 5-minute duration, we replace missing data with the average EDA value over that segment.

Model design and training

For this analysis, we only considered CGM segments that contained signals for the three sensors (ECG, PPG, and EDA), which amounts to an average of 81% of all CGM recordings for which the ECG signal is available. To predict hypoglycemia from multiple sensing modalities, we follow a “late-fusion” approach in which we train separate models for each modality (ECG, PPG, EDA), and then combine their predictions to obtain a final hypoglycemia prediction; see Fig. 8. Details of the architecture for each modality and the fusion model, as well as the training configuration, are described below.

Multimodal architecture for hypoglycemia detection using ECG, PPG, and EDA. Predictions from modality-specific models (InceptionTime for ECG and PPG, Conv1D-BiLSTM for EDA) are averaged and combined using logistic regression for final classification. N denotes the number of analysis windows for each sensing modality over the 5-minute period between CGM readings.

ECG and PPG

We used InceptionTime30 as the backbone architecture for ECG and PPG. InceptionTime is well-suited for time-series data due to its ability to capture features at multiple temporal scales through parallel convolutional filters of varying kernel sizes. The model comprises six InceptionBlockPlus modules. In each of them, the input tensor passes through a bottleneck layer (1 × 1 convolution) that maps input channels to 32 outputs. Subsequently, it undergoes three parallel convolutional operations with kernel sizes 40, 20, and 10, all using padding to maintain the size of the temporal dimension. Additionally, the input tensor is processed through a max pooling layer with (kernel size, stride, padding) = (3, 1, 1) followed by a 1 × 1 convolution layer. The outputs of these four paths (three convolutions and max pooling) are concatenated along the channel dimension, resulting in an output channel size of 128 (32 × 4) followed by a dropout layer with a rate of 0.1. ReLU activation is applied in layers 1, 2, 4, and 5 within each InceptionBlockPlus. There is a residual connection every three Inception modules, specifically at layers 3 and 6. After the 6 Inception blocks, the model output is passed through an AdaptiveAvgPool1d layer, which reduces the temporal dimension to 1, followed by a fully connected layer that maps the output to a single value (with dropout rate of 0.1). To ensure the model predicts probabilities, a sigmoid layer is added at last. For ECG, the InceptionTime model consumes 3-second windows, whereas for PPG a separate InceptionTime model consumes 30-second windows. For each signal, the model generates the probability of hypoglycemia for the corresponding analysis window as a single output. In a final step, we compute an average probability pECG across all ECG 3-second windows associated with a CGM reading (5 minutes), and separate average probability pPPG across all PPG 30-second windows associated with the same CGM reading.

EDA

Given the non-pulsatile nature of electrodermal activity, we developed a custom model that consumes the 5 minutes of EDA recordings prior to each CGM reading. The model consists of two 1D convolutional layers followed by a Bidirectional Long-Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM), a recurrent neural network architecture that combines forward and backward predictions to improve predictions31. We use the output of the BiLSTM at the last timestamp as an embedding and pass it through a fully connected (FC) layer to generate the probability of hypoglycemia pEDA. The first convolutional layer has 4 output channels, a kernel size of 12, a stride of 6, and padding of 3, while the second layer has 8 output channels, a kernel size of 8, a stride of 5, and padding of 2. Each convolutional layer is followed by ReLU activation and Batch Normalization32. These convolutional layers effectively down-samples an input sequence of length by a factor of 30: from 1,200 samples (5 minutes at 4 Hz) to 40 samples. The resulting feature map is reshaped and passed through a one-layer Bi-LSTM, which captures temporal dependencies in the EDA signal. We also evaluated a model that decomposed EDA signals into phasic (skin conductance responses) and tonic (skin conductance levels) channels33 and fed the two channels to the CNN-BiLSTM network. Results for both approaches were comparable, so we are reporting the simpler of the two.

Multimodal integration

Once hypoglycemia predictions are obtained from each modality (pECG, pPPG, pEDA), we feed them to a logistic regression model that is trained to produce a final estimate of the probability of hypoglycemia for each 5-minute interval; see Fig. 8.

Training protocol

Models for each individual modality and multimodal integration are trained using stratified 5-fold cross-validation to ensure that the euglycemic-to-hypoglycemic ratio is preserved across training and validation splits. For optimization, we use Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with a learning rate of 0.0005. Given the significant class imbalance in the dataset, where euglycemic samples dominate, we employ a weighted binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss, as follows:

where w represents the ratio of euglycemic to hypoglycemic CGM readings. This weighting ensures that hypoglycemic instances receive greater emphasis during training, addressing the imbalance and improving the model’s ability to detect rare hypoglycemic events.

Experimental results

We evaluate model performance using predicted accuracy at Equal Error Rate (EER) as the primary evaluation metric, as it balances false positives and false negatives, ensuring fair comparison across modalities. Results for each individual modality (ECG, PPG, EDA) and the joint model are shown in Fig. 9. ECG consistently achieves the best accuracy at EER across all subjects, outperforming both PPG and EDA. PPG shows moderate performance but with notable variability within and between subjects, as expected given that PPG has higher susceptibility to motion artifacts. The EDA signal provides accuracy close to chance level, suggesting that this modality alone is unsuitable for the task. Finally, the joint model (logistic regression) outperforms the individual models, though differences with the ECG model are only significant at α = 0.05 for 5 out of the 8 subjects.

Limitations

The main limitation of the PhysioCGM dataset is the relatively small number of participants in the study and the narrow age range (24–41 years). For this reason, we focused the validation studies on subject-dependent models. Given the large interindividual differences in physiology relative to the subtler changes in physiological variables due to hypoglycemia, we did not consider developing subject-independent models. Several strategies could be used to validate the generalization properties of our models, including leave-one-subject-out cross-validation (i.e., train on N-1 subjects, validate on the held-out subject), as we have done in previous work on CGM analytics34, or donor-receptor studies, where data from test subjects is evaluated on personalized models from training subjects matched for age (or age groups), gender and other relevant descriptors (e.g., BMI, A1c).

The study was conducted on patients with T1D because of the higher incidence of hypoglycemia, which can have life-threating consequences in the short term. Hypoglycemia is less common in patients with T2D unless they are being treated with insulin or sulfonylureas35,36. Hypoglycemia can lead to similar physiological changes (e.g., elevated heart rate, sweating) in both conditions, so our approach could in principle be used with T2D patients, though this will need further research.

Data availability

The complete dataset is available at figshare21.

Code availability

The preprocessing and validation code is available at https://github.com/PSI-TAMU/PhysioCGM. Please refer to the readme.md file included in this repository.

References

ADA. American Diabetes Association: statistics about diabetes, http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/ (2021).

Shamoon, H. et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. New England J. Med. 329, 977–986, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199309303291401 (1993).

Nathan, D. M. et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. New England J. Med. 353, 2643–2653, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa052187 (2005).

DCCT Research Group. Epidemiology of severe hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial. The DCCT Research Group. The American journal of medicine 90, 450–459 (1991).

Daskalaki, E. et al. The potential of current noninvasive wearable technology for the monitoring of physiological signals in the management of Type 1 Diabetes: literature survey. J. Med. Internet. Res. 24, e28901, https://doi.org/10.2196/28901 (2022).

Eckert, B. & Agardh, C. D. Hypoglycaemia leads to an increased QT interval in normal men. Clinical physiology (Oxford, England) 18, 570–575, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2281.1998.00138.x (1998).

Singh, J. P. et al. Association of hyperglycemia with reduced heart rate variability (The Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiology 86, 309–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00920-6 (2000).

Li, J. et al. Noninvasive blood glucose monitoring using spatiotemporal ECG and PPG feature fusion and weight-based choquet integral multimodel approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks and Learning Systems 35, 14491–14505, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3279383 (2023).

Schechter, A. et al. A prototype of a new noninvasive device to detect nocturnal hypoglycemia in adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes—a pilot study. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics 14, 683–689, https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2012.0002 (2012).

Saeed, M. et al. Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care II: a public-access intensive care unit database. Critical Care Medicine 39, 952–960 (2011).

Moody, G. B. & Mark, R. G. The impact of the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine 20, 45–50, https://doi.org/10.1109/51.932724 (2001).

Banos, O., Garcia, R. & Saez, A. MHEALTH [Dataset]. UCI Machine Learning Repository https://doi.org/10.24432/C5TW22 (2014).

Kahn, M. Diabetes [Dataset]. UCI Machine Learning Repository https://doi.org/10.24432/C5T59G (1994).

Ledezma, C. A., Severeyn, E., Perpinan, G., Altuve, M. & Wong, S. in Proc. Annual Intl. Conf. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2738–2741.

Marling, C. & Bunescu, R. in Proc. CEUR Workshop. 71.

Dubosson, F. et al. The open D1NAMO dataset: A multi-modal dataset for research on non-invasive type 1 diabetes management. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 13, 92–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2018.09.003 (2018).

Porumb, M., Stranges, S., Pescapè, A. & Pecchia, L. Precision medicine and artificial intelligence: a pilot study on deep learning for hypoglycemic events detection based on ECG. Scientific Reports 10, 170, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56927-5 (2020).

Nazari, G. et al. Psychometric properties of the Zephyr BioHarness device: a systematic review. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 10, 6, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-018-0094-4 (2018).

McCarthy, C., Pradhan, N., Redpath, C. & Adler, A. in Proc. IEEE EMBS International Student Conference 1–4 (2016).

ZephyrTechnology. BioHarness 3 Log Data Descriptions, https://www.zephyranywhere.com/media/download/bioharness-log-data-descriptions-07-apr-2016.pdf (2016).

Quamer, W. et al. PhysioCGM: A multimodal physiological dataset for non-invasive blood glucose estimation. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28136294 (2025).

Bergenstal, R. M. et al. Recommendations for standardizing glucose reporting and analysis to optimize clinical decision making in diabetes: the Ambulatory Glucose Profile. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 7, 562–578, https://doi.org/10.1177/193229681300700234 (2013).

Battelino, T. et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 42, 1593–1603, https://doi.org/10.2337/dci19-0028 (2019).

Makowski, D. et al. NeuroKit2: A Python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behavior Research Methods 53, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01516-y (2021).

Elgendi, M. Optimal signal quality index for photoplethysmogram signals. Bioengineering 3, https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering3040021 (2016).

Chen, S. et al. Multi-view cross-fusion transformer based on kinetic features for non-invasive blood glucose measurement using PPG signal. IEEE J. Biomedical and Health Informatics, https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2024.3351867 (2024).

Kleckner, I. R. et al. Simple, transparent, and flexible automated quality assessment procedures for ambulatory electrodermal activity data. IEEE Tran. Biomedical Engineering 65, 1460–1467, https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2017.2758643 (2017).

Hölzen, L., Schultes, B., Meyhöfer, S. M. & Meyhöfer, S. Hypoglycemia Unawareness-A Review on Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Biomedicines 12 (2024).

Prendin, F., Del Favero, S., Vettoretti, M., Sparacino, G. & Facchinetti, A. Forecasting of glucose levels and hypoglycemic events: head-to-head comparison of linear and nonlinear data-driven algorithms based on continuous glucose monitoring data only. Sensors 21, 1647, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21051647 (2021).

Ismail Fawaz, H. et al. Inceptiontime: Finding alexnet for time series classification. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 34, 1936–1962 (2020).

Graves, A., Fernández, S. & Schmidhuber, J. in Proc. Int. Conf. Artificial Neural Networks. 799–804 (Springer).

Bjorck, N., Gomes, C. P., Selman, B. & Weinberger, K. Q. in Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Benedek, M. & Kaernbach, C. Decomposition of skin conductance data by means of nonnegative deconvolution. Psychophysiology 47, 647–658, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00972.x (2010).

Gutierrez-Osuna, R., Kerr, D., Mortazavi, B. J. & Das, A. CGMacros: a scientific dataset for personalized nutrition and diet monitoring. PhysioNet. https://doi.org/10.13026/3z8q-x658 (2025).

Christou, M. A., Christou, P. A., Kyriakopoulos, C., Christou, G. A. & Tigas, S. Effects of Hypoglycemia on Cardiovascular Function in Patients with Diabetes. International journal of molecular sciences 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119357 (2023).

Alwafi, H. et al. Incidence and prevalence of hypoglycaemia in type 1 and type 2 diabetes individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 170, 108522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108522 (2020).

Oresti, B. et al. mHealthDroid: a novel framework for agile development of mobile health applications. Ambient Assisted Living and Daily Activities, 91–98 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NSF award 2037383.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Waris Quamer and Mu-Ruei Tseng were responsible for data analytics and curation, implementation of deep-learning models, and manuscript preparation. Kathan Vyas and Darpit Dave, PhD, were responsible for data ingestion during human subject studies. Carolina Villegas, PhD, was the study coordinator, point of contact with participants and ensured adherence to the experimental protocol and data uploads. Siripoom McKay, MD, and Daniel DeSalvo, MD, led the human subjects study design, provided medical oversight to the research team, and served as co-PIs on the NSF award. Madhav Erraguntla, PhD, was responsible for designing statistical ML models from ECG, and served as co-PI on the NSF award. Gerard Cote, PhD, was PI on the NSF award, provided leadership and research coordination across both sites, as well as biomedical signal processing expertise. Ricardo Gutierrez-Osuna, PhD, was co-PI of the NSF award and responsible for the development of deep-learning models and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Daniel J. DeSalvo has served as an independent consultant for Dexcom and Insulet separate from this work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quamer, W., Tseng, MR., Vyas, K. et al. A multimodal physiological dataset for non-invasive blood glucose estimation. Sci Data 12, 1822 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06090-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06090-6