Abstract

India has set an ambitious target of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2070. Road transport, contributing to 12% of India’s CO2 emissions, plays a significant role in exacerbating urban air pollution. Given India’s swift urbanization, CO2 emissions from this sector could potentially double by 2050, jeopardizing climate goals. We present CHETNA-Road, a comprehensive 500-meter gridded city traffic emissions dataset for 15 Indian cities derived from street-level floating car data (FCD) based on GPS position and speed of individual vehicles. We applied statistical and machine-learning techniques to improve data quality and extrapolated data to cover all city traffic instead of only the vehicles equipped with GPS using fuel consumption data. We estimated daily CO2 and ten major pollutant emissions using the COPERT model, which includes speed and vehicle-type dependent emission factors. Finally, we evaluated our dataset against global coarser resolution emission datasets, including Carbon-Monitor cities, EDGAR, and CAMS. Our dataset provides critical insights into India’s road traffic emissions and serves as a foundation for targeting congestion and pollution reduction strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

India faces significant challenges in balancing economic development with environmental sustainability as the world’s most populous nation and a rapidly growing economy1. India has committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, suggesting transformative changes to key sectors, including road transportation. Road transport is a major contributor to urban air pollution and accounts for 12% of India’s energy-related CO2 emissions1. As India is projected to attain high middle-income status by 20472, the demand for private mobility, goods transportation, and fuel consumption is expected to rise significantly. India’s rapid urbanization would also drive the expansion of road transport networks to meet mobility demands. Although road network expansion is typically seen as a catalyst for socioeconomic development, it can further exacerbate the existing problem of urban air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. If the current trends continue, the road transport CO2 emissions will likely double by 20501. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that India’s energy demand and CO2 emissions will peak in the 2040 s and decline marginally afterward. However, continued reliance on gasoline and diesel by the increased use of private cars and trucks may challenge India’s long-term climate objectives. Hence, we see an urgent need for data-driven strategies to mitigate emissions and improve urban air quality.

Daily gridded high-resolution emission data provide several advantages to quantify city traffic emissions and improve the implementation of emission reduction policies. Such granular data enables us to identify emission hotspots at a street or neighborhood level and allows for targeted interventions to optimize the traffic flow in congested areas. For instance, a high-vehicle-density city (Mumbai) may require different strategies compared to smaller cities (Guwahati), which has a relatively low vehicle density. Daily emission data also provides insights into temporal variations, including mobility differences between weekdays and weekends, seasonal trends, implementation of mobility restriction policies (COVID-19 lockdown), etc. Access to temporal mobility patterns allows us to enforce dynamic measures like congestion pricing to reduce gridlocks and also improve air quality. The traffic demand management systems, for example, congestion relief zones, charge vehicles to access the roads during peak times. Such management systems have already been implemented in Manhattan, New York City3, London4, Stockholm, and Gothenburg5, among others. However, Indian cities have yet to adopt such congestion pricing policies, but there is a growing interest in considering these possibilities6. Implementing congestion pricing can be a sensitive topic depending on the acceptability among commuters. A study7 on the Indian perspective on congestion pricing found that individuals with higher income and education had a higher likelihood of accepting congestion pricing. The growing income levels among Indian demographics as a result of the country’s economic growth could make the implementation of such policies more feasible. In addition to the emission reduction, the major perceived benefits of these policies were reduced travel times and increased public transport occupancy.

To reduce urban emissions, India has implemented several policies, particularly in the road transport sector. India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) launched the National Clean Air Programme8 (NCAP) in 2019 to improve the air quality in over 100 Indian cities. The measures include promoting public transport, cleaner fuel transition, and implementing strict vehicle emission norms. As India is the world’s fourth largest car manufacturer, the government is keen to promote the adoption of electric vehicles (EV) through the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles (FAME) scheme under the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP, 2020). This scheme provides financial incentives for purchasing hybrid and electric vehicles and to develop charging infrastructure. The main goal is to reduce dependence on fossil fuels through EV adoption and to cut down vehicular emissions. India’s National Smart Cities Mission9 (2015) aimed to develop 100 smart cities across India, which are set to be sustainable and citizen-friendly. Despite these efforts, we find a gap in the literature about the availability of high-resolution open-source road transport emission datasets specific to India. For high-income countries like the United States, there are datasets like Vulcan10 and Hestia11 that provide high spatiotemporal CO2 emission data for US cities. Global transport emissions datasets exist: EDGAR12 (Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research) and CAMS13 (Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service). These datasets provide limited insights into city-scale anthropogenic transportation emissions because they are based on downscaling national totals using simple proxies (road networks) and are available only at a monthly or annual frequency, lacking the granularity necessary for city-level analysis in India. Carbon-Monitor Cities14 offers near-real-time daily gridded emission data for 1500 cities worldwide (including several Indian cities), but the methodology is not tailored to the unique characteristics of Indian cities. They used a city-wide average congestion index for daily variations, which had no clear geographical coverage and only covered a few cities in India, with the rest extrapolated using EDGAR data. A study15 on Delhi traffic flow estimates hourly emissions for major pollutants (oxides of nitrogen, particulate matter) for 2018. The data used in that study was limited to 72 survey locations spread throughout the city and did not focus on greenhouse gas emissions. Such limitations make it challenging to develop effective city-level policies to address traffic congestion and urban air pollution.

We present the CHETNA-Road16 (City-wise High-resolution Carbon Emissions Tracking and Nationwide Analysis) dataset to address these limitations. It is a street-level daily gridded city road transport emission dataset for 15 Indian cities at a 500-meter resolution, which includes CO2 emissions and ten major pollutants, namely nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOC), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), ammonia (NH3), lead (Pb), and black carbon (BC). Using street-level mobility data and advanced machine-learning techniques, we captured the spatial and temporal patterns in vehicle mobility. Subsequently, we used the COPERT17 model to estimate the vehicular emissions. Aggregated from a native resolution of individual street segments to a 500-meter gridded spatial scale, our dataset’s granularity would enable policymakers to design targeted policies, for instance, congestion relief zones, to reduce emission hotspots and gridlocks. Our dataset bridges the critical literature gap by offering city-level insights into CO2 and other major pollutants to align with India’s long-term climate and air quality goals.

Methods

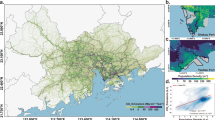

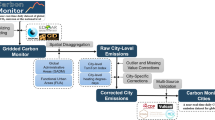

We developed a bottom-up framework (shown in Fig. 1A–D) to construct a gridded CO2 and pollutant emission inventory for 15 major Indian cities. This framework uses mobility data collected from Nexqt18 and the COPERT17 model to construct a street-level daily emission grid at a 500-meter resolution.

Mobility data

Our emission grid is based on the Nexqt18 mobility data for 2021. We collected mobility data, i.e., street-level floating car data (FCD), based on the GPS position and speed of individual vehicles. FCD refers to the data collected from vehicles equipped with geolocation technologies like GPS. It captures the timestamps, speed, count, and direction of travel. The data is anonymized for privacy protection, providing valuable information for traffic analysis and insights into near-real-time road usage. We compiled GPS mobility data from individual vehicles (aggregation of unique vehicles observed on each road segment) for 15 Indian cities: Bengaluru, Chandigarh, Chennai, Delhi, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Indore, Jaipur, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mangaluru, Mumbai, Pune, Tiruppur, and Vadodara (Fig. 2A). These cities cover the full extent of the country, giving us a good representation of urban mobility diversity in terms of geography and demographics. This set also includes major metropolises (Delhi and Mumbai) and relatively smaller urban centers (Guwahati and Mangaluru). We set the boundaries of these urban areas (subdivided into wards) as defined by their respective municipal corporations, for instance, Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC)19 for Mumbai. The floating car data reports the total vehicle count in a road segment (size ranging from 10–50 meters) and average vehicle speeds for all streets in the city. It is an hourly time series consisting of data related to two types of vehicle fleets: cars and trucks. The data covers all kinds of passenger cars. For trucks, it includes both light commercial vehicles (Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR) < = 3.5 tonnes) and heavy-duty trucks (GVWR > 3.5 tonnes). As this data accounts only for a fraction of the vehicles fitted with geolocation sensors, there is a large proportion of unaccounted vehicles (around 50–80%, depending on the city and road segment). It is to be noted that the data doesn’t account for all vehicles fitted with the geolocation sensor. These unaccounted vehicles included cars, trucks, and other vehicle fleets commonly found on Indian roads: two-wheelers (motorcycles) and three-wheelers (auto-rickshaws). In the following sections, we explain how we extrapolated our GPS data from a subset of vehicles, including gaps in the data, to all the vehicles each hour, in each road segment, and city.

Model performance in predicting vehicle count and speed in different Indian cities. (A) Map of Indian cities considered for this study (marker size corresponds to city population). (B) Average R2 scores for 15 Indian cities showing the performance of the machine learning model to gap-fill missing floating car GPS data for each road type and different periods (marker size shows city population). The number of data records in the X-axis was shown on a natural log scale. Time series showing actual and predicted (C) daily mean vehicle count and (D) daily mean vehicle speed in Chandigarh for 2021. Time series showing the percentage difference between the predicted and actual values for (E) vehicle count and (F) vehicle speed, with its interquartile ranges for 15 cities.

Data imputation

The floating car data frequently have missing values, which we categorized into small and large gaps. Small gaps refer to instances where a few hourly records are missing in a day, while large gaps are missing data over longer periods, ranging from days to weeks within a year. Figure 1A shows the data processing steps, which is the first stage of our framework. To fill the missing gaps, we used two techniques corresponding to the type of gap. We applied statistical imputation on the small gaps using a threshold of 12 hours. If a day had at least 12 hours of data present, we filled the missing 12 hours of data using the global hourly distribution unique to each road segment. This process imputed around 10% of the missing vehicle count and speed values. Then, we used a machine-learning model to predict the missing hourly records in the large gaps. The machine-learning model was trained on date-time and street-related predictors collected from the mobility dataset. The date-time predictors include hour, day, month, and quarter, as well as time of day, day of the week, and week of the year. Street-related predictors include road type, lane number, speed limit, and the annual average of vehicle count and speed. We tested various machine learning models, and the Light Gradient-Boosting Machine20 (LightGBM) performed best. Training of the machine learning model was done on 80% of data and tested on 20% of unseen data. The R2 values of LightGBM on the test set are 20–30% higher than a simple linear regression model. Considering the huge size of floating car data, ranging from tens to hundreds of gigabytes, we chose LightGBM for its high performance and low time complexity21 compared to other ensemble boosting (XGBoost) and bagging (Random Forest) machine learning models.

Imputation model performance

We obtained R2 values on the testing set by predicting the missing vehicle count and speed for 15 cities (Fig. 2B). We trained separate machine learning models (LightGBM) using the date-time and street-related predictors to predict vehicle count and speed. We averaged the R2 values (shown in Fig. 2B) to show the overall performance in predicting vehicle count and speed. For most cities, these values are greater than 0.60, and we observe from Fig. 2B that R2 increases with the increase in size of the dataset, implying that with a larger training set, the machine learning model performs better. Tiruppur city, having the lowest number of data records, shows the lowest performance. However, machine learning models require vast amounts of training data to perform optimally; their performance could be affected by many other factors, for example, unbalanced data distribution, noise, and the presence of outliers. Table 1 shows the performance metrics of the machine learning model. We showed standard regression metrics: the R2 and RRMSE (Relative Root Mean Squared Error) for 15 cities. Figure 2C,D shows the time series of actual and predicted variables in the mobility variables of interest: vehicle count and speed, respectively, for Chandigarh. The testing set is randomly selected, making up 20% of this time series in Fig. 2C,D. We observe that the model captures global trends and local fluctuations well, both in the case of predicting vehicle count and speed. We show the mean percentage difference between the actual and predicted vehicle count values in Fig. 2E and vehicle speeds in Fig. 2F for 15 cities, along with their interquartile ranges. We observe that the predicted values deviate from the actual by around 10% more or less in both cases (count and speed prediction). This shows that our model is robust enough to capture the spatiotemporal patterns of vehicle counts and speeds to make a good prediction model. Note that we used mainly the R2 to evaluate the performance of the machine learning model as it is the most informative22 metric for the regression analysis, and a value usually greater than 0.6 is acceptable in climate sciences23. We also provided other metrics (RRMSE) for comparison, but they were not used in model evaluation.

Model predictive power analysis

We used two techniques to understand our model’s prediction behavior. First, we performed an analysis to understand the influence of temporal and spatial information on the model prediction. We show the Chandigarh streets from our dataset in Fig. 3A. Here, the streets are classified into five types. The different road types are numbered from 1 to 5, where the major roads are categorized into 1–3 types (usually highways, arterials, primary roads) and the minor roads into 4–5 types (local roads). The proportion of road type 5 (in pink) is the highest in the city, which denotes the smallest streets (the lowest functional hierarchy of roads). To assess if the model’s prediction performance is influenced by the temporal or spatial information in the data: (i) we computed R2 scores for all temporal values (hourly values of the target variables: vehicle counts and speeds) in the city streets, comparing the observed and predicted temporal patterns (we subtract the mean value from the time series of each road segment to keep only the temporal patterns); (ii) we also computed R2 scores for all spatial values (annual average of the target variables: vehicle count and speed per road segment) by comparing the temporal mean over one year of observed and predicted values for each street. In Fig. 3B, the major roads (1,2, and 3 types) have the highest R2 score, with the lowest being in road type 5. The major roads with good temporal R2 scores also correspond to the roads with the highest proportion of vehicle counts. This shows that our model captures the temporal variability well for the majority of the vehicles in the city. Figure 3C shows the density plots of the R2 scores for all types of roads, and noticeably, the temporal R2 scores for the major roads lie between 0.2 and 0.6, and for road type 5, the scores are mainly below 0.3. From Fig. 3D, we found that the model’s overall predictive power comes from spatial patterns, as the spatial R2 score is greater than 0.8. The temporal patterns also show their contribution to the model performance but to a greater extent in the major roads of the city. We note that the mean vehicle speed prediction in Fig. 2D appears to be underestimated. This speed prediction mean calculation is dominated by the smaller local roads (road type 5), which experience lower speeds. However, most of the traffic flow is in road types (1–4), where we have the higher R2 scores (Fig. 3B), and thus a good prediction model.

Model predictive power analysis. (A) Road map showing the different road types in Chandigarh city. Road types classified from 1 to 3 are major roads of the city (highways, arterials, primary roads), while road types 4 and 5 are the minor roads (local roads). (B) Mean R2 between the actual and predicted temporal values (hourly values of the target variables: vehicle counts and speeds) for all roads in each road type, and mean traffic counts for all road types. (C) Density plots of R2 between the actual and predicted temporal values for each road type. (D) Mean R2 between the actual and predicted temporal values; and the actual and predicted spatial values (annual average of the target variables: vehicle count and speed) for all roads. (E) Bar plot showing the percentage of SHAP influence in making predictions by individual predictors. The mean variable is the annual mean vehicle count and speed used to predict hourly vehicle count or speed, respectively. (F) Beeswarm plot showing the influence of predictor value on the final prediction.

Second, we used the SHAP24 (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework to understand the influence of predictors in predicting vehicle count and speed values for floating car data. It can be used to rank the predictors in order of their contribution to the model output. If a predictor has a significant impact on the outcome, the magnitude of the SHAP value is high (positive or negative). The computation of SHAP values for large datasets takes significant resources and is computationally expensive, so we selected 20000 data points using random sampling25 to analyze the SHAP influence. We showed the predictor significance as an influence percentage in Fig. 3E. Here, we ranked the predictors from the most influential to least in two categories: date-time and street-related predictors. The hour and week of the year are major contributors to the final prediction (in the date-time category). The mean variable value is the mean vehicle count or speed, depending on the prediction model (as we built separate models to predict vehicle count and speed) is the most important predictor for the model. The road type is the next most influential predictor in the street-related predictors category. We understand how the magnitude of the predictor affects the model output from the beeswarm plot in Fig. 3F. A higher mean vehicle count or speed value (high and low values are in comparison to the median value of the predictor) positively impacts the model output. It also shows that the presence of low values of road type (1 to 3, i.e., major roads) adds to the model prediction power. We observe some instances in the week of the year and month predictors where lower values (values before June, considering the median) have some negative impact on the prediction, while the day of the week (from Monday to Wednesday) shows a positive impact on prediction. Overall, the street-related predictors show the highest contribution to the model prediction.

Data scaling

Our floating car data encompasses only vehicles fitted with a GPS sensor. To understand the proportion of vehicles counted in FCD, we computed the fuel consumed by vehicles present in the FCD and compared it with the total city fuel consumption. The average proportion of fuel consumed by vehicles in FCD is 35% (see below for how this percentage is derived). This percentage varies depending on the city, as shown in Table 1. Guwahati shows the highest value (88.1%). Major cities: Bengaluru, Chennai, Delhi, and Hyderabad have FCD fuel consumption in the range of 20–40%, while Mumbai only has 11%. So, a large chunk of vehicles was not present in our dataset. We performed the data scaling process to complete the missing proportion of vehicles. We used fuel consumption data to estimate the proportion of unaccounted vehicles in the data. The Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell (PPAC)26 of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, Government of India, provides annual fuel consumption data for each state in India. Since this is state-level fuel consumption data, we used the gridded population data from the Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL)27 to compute the city-level fuel consumption values (within the city boundary definitions provided by the respective city’s municipal corporation). PPAC also provides an annual report on fuel consumption in different states in India. This report includes the proportion of fuel used in different sectors, including ground transport, industry, etc. We used this information to adjust the city fuel consumption values accordingly. Our fleet structure in the data comprises only cars and trucks, so we assumed all petrol is used for cars and all diesel for trucks (after adjusting the fuel proportion values).

We do not have information on vehicles running on compressed natural gas (CNG). However, CNG consumption is relatively small compared to petrol, accounting for approximately 8.3% of petrol consumption in India. We based this estimate on a comparison between national annual fuel consumption values for petrol26 and CNG28. Our fleet composition is missing the two and three-wheelers often found in Indian streets. However, the estimated proportion of cars would act as a proxy for the missing two and three-wheelers. With the data scaling process, we estimated the total proportion of vehicles at an hourly frequency in the city streets.

To do this, we derived a correction factor (CF):

where, r is the road or street, and t is the time in hours. Count is the vehicle count from floating car data. Fuel consumption is a function that inputs vehicle speed to output the vehicle fuel consumption in grams per kilometer using the equations from the COPERT17 model. Road length is the length of the road segment considered to make the vehicle count. Cityfuel is the city’s fuel consumption computed from PPAC data. We devised two correction factors for cars and trucks separately using the petrol and diesel consumption data, respectively. We used this correction factor to estimate the missing proportion of vehicles (both cars and trucks).

As shown in Eq. 2, we updated the hourly vehicle counts by multiplying them with the correction factor computed from Eq. 1. The percentage of fuel consumed by vehicles in the floating car data shown in Table 1 (FCD%) can be derived by the following formula:

Emission modeling

After the data imputation and scaling process, we now had complete mobility data for all streets on an hourly scale in the city. Here, we estimated the CO2 and pollutant emissions using the COPERT17 model on the hourly mobility data. COPERT is the European Union’s standard tool that follows the 2006 IPCC guidelines to calculate road transport greenhouse gas emissions. Their software provides an option to apply the model to different countries, including India. We used the COPERT-5.8.1 version to estimate Indian road transport emissions at an hourly frequency and then aggregated the emissions to daily values. In Fig. 4A, we showed the gridded annual CO2 emissions for Chandigarh at a 500-meter resolution. We observe emission hotspots and the spatial emission patterns here. We showed the time series for 2021 daily CO2 emission estimates for Chandigarh in Fig. 4B. To estimate these emissions, we used the COPERT curves shown in Fig. 4C. We have two CO2 emission curves, one for the car fleet and the other for trucks. Our current methodology does not include emission factors for other vehicle species (notably, two-wheelers and three-wheelers) (as discussed in the previous section). The emission curves are mapped to the average vehicle speed values to output the corresponding emission factor for cars and trucks separately. We used the information on the Indian road fleet structure provided by the Parivahan29 portal from the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways of India, along with the temperature and humidity data collected from ERA530 gridded data, to construct these COPERT emission curves. Using the emission factors in Fig. 4C, we compute city-scale CO2 emissions with the following formula:

where, V is the average speed of vehicles in the r road segment, C is the vehicle count, and S is the distance traveled in the r road segment, t is time in hours. We obtain the emissions at an hourly scale and sum them up over the 24-hour period to produce daily totals. Then, the daily time series is transformed into a 500-meter gridded dataset. We divide the city area into uniform 500 × 500-meter grids using the city boundary polygon. To add the street-level emissions into the gridded dataset, we map the streets’ coordinates with the nearest corresponding points on the grid and sum them. This way, we computed daily gridded CO2 emissions for all 15 cities at a 500-meter resolution. Since our methodology involves the use of fuel consumption data from PPAC, we compared the estimated annual CO2 emissions for 15 cities with the city fuel consumption values. We obtained the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.94, which indicates a strong positive correlation between the annual city CO2 emissions and its fuel consumption. Hence, our emission estimates are consistent with the PPAC’s fuel consumption values.

Emission analysis in different Indian cities. (A) Map showing total annual CO2 emissions (in tonnes/year) in Chandigarh city for 2021. (B) Time series showing daily CO2 emissions (in tonnes) in Chandigarh city for 2021. (C) COPERT curves generated to compute CO2 emission factors as a function of vehicle speed. (D) Per distance annual CO2 emissions (in tonnes/km) (logged scale) in comparison with city vehicle density (logged scale). (E) Bar plot showing 10 different annual pollutant emissions (tonnes/year) in Chandigarh in 2021. (F) Heatmap showing the 2021 annual pollutant emissions (X-axis) in 15 Indian cities (Y-axis).

We showed the scatter plot of vehicle density (number of vehicles per square km) to the CO2 emissions per km in Fig. 4D. We observe a linear trend where the increase in vehicle density increases the CO2 emissions per km. Vehicle density is computed by dividing the average total vehicle counts for all roads in the city by the city area. For CO2 emissions per km, we divide annual total CO2 emissions by the total road length of the city. The city with the highest vehicle density is Mumbai on our list, and as expected, it has the highest CO2 emissions per km (for 2021). Similarly, we built COPERT emission curves for 10 major vehicular pollutants, namely nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM₁₀), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOC), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N2O), ammonia (NH₃), lead (Pb), and black carbon (BC). We computed the pollutant emissions following the same approach that we used to compute CO2 emissions (see Eq. 4). Figure 4E shows the bar plot of ten major pollutants in Chandigarh for 2021. These emissions are lower than CO2 emissions, and NOX is the second most significant pollutant. This pattern can be observed in the inter-city pollutant emission comparison made through a heatmap in Fig. 4F. Bengaluru, Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, and Mumbai showed high concentrations of NOX and CO. In Fig. 5, we showed CO2 emission maps for six major Indian cities. These cities include Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, and Delhi. Here, we used a common emission scale for all cities, and Mumbai shows the highest spatial distribution in CO2 emissions.

Data quality

We observed some issues in data quality for the mobility data. The main issue was the artificial boosting of vehicle counts towards the end of the year, as the data provider likely enhanced the number of sources. This caused an abnormal spike in vehicle counts for some time period. We used the monthly national fuel consumption data (for the year 2021) provided by the Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell (PPAC) of India to correct these spikes during the data scaling process.

Data Records

The CHETNA-Road16 products are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28330067. The traffic emission data files are stored as netCDF files with the unit tonnes for each grid. We provided gridded values for 15 Indian cities (Bengaluru, Chandigarh, Chennai, Delhi, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Indore, Jaipur, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mangaluru, Mumbai, Pune, Tiruppur, and Vadodara) with a spatial resolution of 500 meters and a temporal resolution of daily. The CO2 emissions are published separately from other pollutants in the “CO2_emissions” folder. All 10 pollutant emissions (nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM₁₀), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOC), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N2O), ammonia (NH₃), lead (Pb), and black carbon (BC)) can be found in the “other_pollutant_emissions” folder. We structured the netCDF files to have three dimensions, namely time, latitude, and longitude. The time dimension includes daily intervals from January 1 to December 31, 2021. The spatial dimensions (latitude and longitude) have a uniform grid with a resolution of 0.005 degrees (approximately 500 × 500 meters) covering the entire city’s area. The emission data (CO2 or other pollutants) is stored under the data variable index in units of tonnes for each grid cell and daily time stamp. We also provide the file attributes: the title of the dataset, units of emissions, name of the city, name of the state, year, and the author.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the CHETNA-Road dataset with other coarser resolution datasets available on ground transport CO2 emissions. These include Carbon-Monitor Cities14, Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR version 8.0, or EDGARv8)12, and Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS-GLOB-ANT version 5, or CAMSv5)13. We ensured the reliability of our dataset with this multi-source comparison. Carbon-Monitor (CM) Cities is a near-real-time daily emission dataset built for 1500 cities worldwide. It focuses on emissions in five sectors, and here, we used emissions from ground transportation to compare with our results. CM-Cities estimated city emissions using a top-down approach by disaggregating the daily national emission inventories into grids using the EDGARv5 spatial activity data. Their process employed city-average TomTom31 congestion data for temporal daily variations without a clear definition of the exact city area represented by these TomTom data. CM-Cities provides emissions for the administrative jurisdiction area of each city and for the Functional Urban Area32, which groups a main city with smaller cities that commute with each other. Here, we used the Global Human Settlement Layer dataset33, which defines the boundary of the Functional Urban Area (FUA). We adjusted the values of CM-Cities based on the population within our city boundary (as defined by the city’s municipal corporation) and the FUA boundary. This way, we had the adjusted emission estimates for CM-Cities within our city boundary definition. The CM-Cities developers noted that input data for cities from less developed nations could possess inherent errors and missing values, impacting the final emission estimates. We showed the time series comparison of daily CO2 emissions in Jaipur for 2021 between CHETNA-Road and CM-Cities data in Fig. 6A. In Jaipur, CHETNA-Road captures slightly higher emission levels than CM-Cities but has similar temporal trends. Notably, we observe the dip in emissions during mid-2021, corresponding to a reduced mobility period due to COVID-19 lockdowns34. This highlights the sensitivity of both datasets to real-world events.

Comparison of CHETNA-Road emission dataset with other standardized datasets. (A) Time series showing daily CO2 emissions (in tonnes) from CHETNA-Road and Carbon Monitor cities data in Jaipur city for 2021. (B) Time series showing monthly CO2 emissions (in tonnes) from CHETNA-Road, CM-Cities, EDGAR, and CAMS data in Jaipur city for 2021. Scatter plot of logged emission values (in tonnes) between CHETNA-Road and (C) Carbon Monitor cities data, (D) EDGAR data, and (E) CAMS data. Jaipur, Mumbai, Delhi, and Bengaluru are annotated.

EDGARv8 and CAMSv5 datasets are published on a monthly scale. EDGARv8 computes emission factors based on activity data to provide anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants on a spatial grid. They estimate CO2 emissions using data from multiple sources35: national statistical institutes (which provide country-specific information), international associations (e.g., IEA for centralized data sources), and also from emission estimation tools like COPERT (to derive the emission factors). For India, additional data sources, including vehicle stock36, were incorporated into the COPERT model to estimate the emission factors. Subsequently, these emissions are simply downscaled using road network maps. EDGARv8 thus ignores congestion patterns and assumes that all the cities of India have the same emission rate per unit of road length, which is not realistic. Although the CM-Cities dataset is exactly similar to EDGARv5 for its mean annual CO2 emissions aggregated over the jurisdiction of each city, it uses daily temporal data from TomTom daily congestion indices, assumed to be representative of the whole city jurisdiction (no hourly variation and no differences in daily variations between roads or districts within the same city). TomTom daily congestion data are only available for selected cities37 in India (including Ahmedabad, Bengaluru, Chennai, Ernakulam, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, Mumbai, New Delhi, and Pune). For cities not covered by TomTom, the congestion data was extrapolated based on the average changes observed in other cities14 within the same country. This makes CM-Cities more precise in accounting for the daily temporal patterns in transport emissions for an entire city, but CM-Cities remains identical to EDGARv5 for spatial patterns within cities. CAMSv5 global anthropogenic emissions data (CAMS-GLOB-ANT) is based on the EDGARv5 data and the emissions provided by the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS)38. CEDS is an open-source annual emission estimates dataset developed at the Joint Global Research Institute in Maryland, USA. Here, they integrated multiple datasets and applied extrapolation techniques to compile a high-resolution emission inventory from 2000 to 2023. Additionally, CAMSv5 also utilized the CAMS-GLOB-TEMPO39 dataset to add the monthly variability details. We used our city boundary polygons to clip and sum the emissions from the gridded EDGARv8 and CAMSv5 datasets. For cities that are too small to fit inside the coarser grids of EDGARv8 and CAMSv5, we used a small buffer (1–5 km extending outwards of our defined city limits).

In Fig. 6B, we compare monthly CO2 emissions in Jaipur for 2021 across CHETNA-Road, CM-Cities, EDGARv8, and CAMSv5 datasets. In the case of Jaipur, CHETNA-Road reports higher emissions (1.5 to 1.7 times higher) than other datasets while having closer temporal patterns with CM-Cities than the EDGARv8 or CAMSv5 datasets. Figure 6C–E, we show the scatter plots between CHETNA-Road’s logged emission values and those from CM-Cities (Fig. 6C), EDGARv8 (Fig. 6D), and CAMSv5 (Fig. 6E). The points around the diagonal line signify the correlation between CHETNA-Road and other datasets. Although the temporal patterns of CHETNA-Road closely align with the CM-Cities data, we see the points relatively spread out because of the difference in emission magnitudes (Fig. 6E). Our dataset shows a higher correlation in emission magnitude when compared with EDGARv8 or CAMSv5. Overall, we observe strong correlations across all comparisons.

We compared CO2 emissions for all 15 cities across the four datasets in Fig. 7A. All cities show emissions from CHETNA-Road comparable in magnitude with EDGARv8 and CAMSv5 datasets. We observe that CM-Cities estimated higher emissions for Bengaluru, Chennai, and Delhi. In Fig. 7B, we compared the mean and the interquartile ranges (shaded) for daily CO2 emissions between CHETNA-Road and CM-Cities. We see that our emission dataset captures temporal patterns similar to those of CM-Cities. This effect is more clear in the monthly comparison between the two datasets in Fig. 7C, where we observe the drop in emissions during May 2021 due to COVID-19 mobility restrictions (as discussed before). We also noticed that the estimated range of emissions in CM-Cities is larger than that of other datasets (on average, CM-Cities have emission estimates 2.7 times larger than CHETNA-Road).

(A) Bar plots showing the total annual emissions in 2021 for 15 Indian cities. Time series comparing the mean and the interquartile range of (B) daily CO2 emissions (in tonnes) between CHETNA-Road and CM-Cities data for 15 cities in 2021. (C) monthly CO2 emissions (in tonnes) between CHETNA-Road, CM-Cities, EDGAR, and CAMS data for 15 cities in 2021.

We would like to note that commercially available floating car data is increasingly being used in ground transport emission studies. For major European cities, there have been efforts to create high spatiotemporal traffic emission maps40 using commercial data. This private data was also used in validating open-source traffic data available for European cities41, which illustrated a high R2 score between the open data and the private floating car data for 75% of European cities included in the study. This shows that our workflow can be adapted to different data sources, including open-source data.

Uncertainty analysis

The main sources of uncertainty in our dataset arise from (i) the data imputation process for missing GPS data using machine learning, (ii) the disaggregation of state-level fuel consumption data into city-level using the gridded population data from GHSL, and (iii) the estimation of the missing proportion of vehicles that do not have GPS reported to our dataset using city-wide fuel consumption data in the data scaling process. The quality of the street-level mobility data: the vehicle count, speed, and fleet structure, is crucial to accurately estimate the daily CO2 and pollutant emissions. We employed a machine learning model to fill the missing gaps in the dataset, and the extent of uncertainty introduced here can be defined with the relative root mean squared error (RRMSE). The interquartile range of RRMSE (error range of the machine learning model in making predictions) is 0.47–0.52, and the mean value is 0.50 (Table 1). Also, our dataset lacked a comprehensive coverage of the vehicle fleet, mainly the count of two-wheelers and three-wheelers. We fixed this problem with the use of fuel consumption data to derive proxies for the missing vehicles. We substituted all the unaccounted vehicles in our data with either cars or trucks (depending on the fuel consumption data), so the overall estimation of CO2 emissions could be on the higher side. However, for the pollutant emissions, the effect is less clear as the two-wheelers and three-wheelers typically have higher emission factors42. So the pollutant estimates could be biased in either direction depending on the missing fleet composition. This use of fuel consumption data to estimate the missing proportion of vehicles could introduce some uncertainties, as it might not match the real-world fuel usage patterns. Moreover, there are some uncertainties associated with the estimation of city-level fuel consumption data (from state-level data) due to spatial mismatches between the population distribution and vehicle activity. In our analysis, we kept the uncertainty of emissions to a minimum by employing advanced techniques, including machine learning and COPERT models, in estimating the emissions. In the CM-Cities14, the 1-sigma uncertainty for road transport was estimated as ± 9.3%. We used this value to compute the confidence intervals of our CO2 emission estimates. To do this, we performed the Monte Carlo simulation, which is widely used in uncertainty analysis. Here, we generated 10000 random samples from a normal distribution using ± 9.3% as the 1-sigma standard deviation. We took the mean, 5th, and 95th percentiles of the simulated data for each city to capture the range of uncertainties. Figure 8 shows the mean value of simulated data from 2021 annual CO2 emissions for 15 cities, along with their confidence intervals.

Temporal uncertainty

We also performed an analysis of the temporal and spatial uncertainty of CHETNA-Road data in comparison to the CM-Cities and EDGARv8 data. Since we had the daily emission time series data from CM-Cities, we compared our daily time series to calculate the temporal correlation or deviation from the CM-Cities data. First, we subtracted the mean for both time series and then normalized the values from 0 to 1 to preserve the temporal information. Then, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient and the relative root mean squared error (RRMSE23) to understand how closely the time series are related. RRMSE is the square root of the ratio between the sum of the squared differences between the true values and predicted values, and the sum of the squared predicted values. RRMSE is easier to interpret where 1 is the highest value, and 0 is the lowest. Table 2A shows the temporal correlation and RRMSE values for 15 cities. The higher correlation values indicate the closeness of the temporal patterns. We notice a high correlation among all cities, with the highest correlation being in Chandigarh (0.74) and Delhi (0.71). The RRMSE shows the uncertainty between the two datasets. In the case of Chandigarh, we see a high correlation (0.75) and also a high RRMSE (0.98). This means the temporal patterns are similar in both datasets, but the magnitudes are different. Meanwhile, Delhi shows a high correlation (0.71) and a low RRMSE (0.16), indicating closeness in both temporal patterns and magnitude.

Spatial uncertainty

EDGARv8 transport emissions dataset is a gridded dataset. We compared the gridded annual mean values in CHETNA-Road with the EDGARv8 gridded values. The resolution of both datasets is different. CHETNA-Road data has a resolution of 500 meters, while EDGARv8 has a resolution of 0.1° (approximately 10 km × 10 km grids). So, we coarsened the CHETNA-Road data to match EDGARv8’s resolution and then flattened the grids into one-dimensional vectors to compute the Pearson correlation coefficient and the RRMSE. Table 2B shows the results from the spatial uncertainty analysis for 15 cities. We notice many cities have a very high correlation, and a few cities show a negative correlation. During the aggregation of CHETNA-Road grids, we lost spatial detail, especially for the cities with smaller surface areas. Such small cities only had a few emission points inside the city boundary, which was not enough to make a meaningful comparison (the number of grid points per city is shown in Table 2). We concatenated all cities’ spatial grids and computed the correlation coefficient and the RRMSE. We have a stronger positive correlation (0.66), but also a relatively higher RRMSE (0.68). This is helpful to understand where the CHETNA-Road dataset stands in comparison to the EDGARv8 data.

Although Delhi shows a temporal correlation of 0.71 and spatial correlation of 0.58 (Table 2) with EDGARv8 datasets, different spatial patterns can be observed (Fig. 9A–C). In the CHETNA-Road dataset (Fig. 9A), CO2 emissions are concentrated in grids with higher road length and traffic activity, whereas EDGARv8 emissions appear more homogenously distributed across the urban area. Our emission estimates are derived from high-resolution Floating Car Data and detailed road network information, which allocates the emissions based on observed traffic activity. This makes sure we actually have higher emissions in grids with congested road segments and dense traffic. Whereas EDGARv8 relies on proxy information (population density, built-up area, and generalized road networks), which results in smoother spatial patterns. This contrast suggests that our activity-based emission model may better capture intra-urban emission heterogeneity than a proxy-driven approach. Finally, these comparisons confirm that CHETNA-Road captures temporal and spatial variations in CO2 emissions in urban areas effectively and aligns well with standardized datasets. The differences observed between the datasets highlight the different methodology and scope of CHETNA-Road, which focuses specifically on road transport emissions rather than broader sectoral aggregations.

Comparison of spatial CO2 emission differences between CHETNA-Road and EDGAR data for Delhi (2021). CO2 emission grid map of (A) CHETNA-Road dataset (coarsened), (B) EDGAR dataset for Delhi. (C) Grid map showing the percentage difference between CHETNA-Road and EDGAR CO2 emissions. (D) Grid map showing the percentage of total road length in Delhi.

Pollutant comparison

We compared 9 pollutants available in EDGARv8 database (nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM₁₀), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOC), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N2O), ammonia (NH₃), and black carbon (BC)) with the pollutants estimated in the CHETNA-Road dataset in the Fig. 10. We observe a stronger correlation (R2 > 0.7) between the two datasets for all pollutants. A few pollutants namely, NOX, PM2.5, PM10, and BC are closer to the 1:1 line, which shows that the magnitudes of these pollutants are closer between the two datasets. For other pollutants, we notice that CHETNA-Road dataset underestimates when compared with EDGARv8 values. CHETNA-Road provides values for lead (PB) which is missing the EDGAR database, so this comparison could not be established.

Data availability

The CHETNA-Road16 dataset is openly available through figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28330067. The repository contains the full dataset in netCDF format, including the 500-meter daily gridded CO2 emissions and 10 pollutant emissions (nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM₁₀), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOC), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N2O), ammonia (NH₃), lead (Pb), and black carbon (BC)) for 15 Indian cities (Bengaluru, Chandigarh, Chennai, Delhi, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Indore, Jaipur, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mangaluru, Mumbai, Pune, Tiruppur, and Vadodara). The CO2 emission data is found in the “CO2_emissions” folder, and the 10 pollutant emission data is found in the “other_pollutant_emissions” folder. The netCDF files have three dimensions, namely time, latitude, and longitude. The time dimension includes daily intervals from January 1 to December 31, 2021. The file attributes include the title of the dataset, units of emissions, name of the city, name of the state, year, and author.

Code availability

The code for plotting the emission maps, time series, and bar plots shown in the paper for 15 cities is included in the GitHub repository, available at https://github.com/rohithteja/CHETNA-ROAD.

References

Transitioning India's Road Transport Sector – Analysis IEA. IEA https://www.iea.org/reports/transitioning-indias-road-transport-sector/executive-summary (2023).

The World Bank In India. World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/india/overview (2024).

Congestion Pricing Program in New York. MTA https://congestionreliefzone.mta.info (2025).

Matters, T. for L. | E. J. Congestion Charge (Official). Transport for London https://www.tfl.gov.uk/modes/driving/congestion-charge (2025).

Congestion taxes in Stockholm and Gothenburg - Transportstyrelsen. https://www.transportstyrelsen.se/en/road/vehicles/taxes-and-fees/road-tolls/congestion-taxes-in-stockholm-and-gothenburg/ (2024).

Introduction of Congestion Pricing, Press Information Bureau. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1797269®=3&lang=1 (2022).

Marazi, N. F., Majumdar, B. B., Sahu, P. K. & Potoglou, D. Congestion pricing acceptability among commuters: An Indian perspective. Res. Transp. Econ. 95, 101180 (2022).

National Clean Air Programme. https://prana.cpcb.gov.in/#/home (2019).

Smart Cities Mission, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. https://smartcities.gov.in/ (2015).

Vulcan Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions… U.S. Greenhouse Gas Center https://earth.gov/data-catalog/vulcan-ffco2-yeargrid-v4 (2025).

Hestia project. https://hestia.rc.nau.edu/.

EDGAR - The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/emissions_data_and_maps (2024).

Soulie, A. et al. Global anthropogenic emissions (CAMS-GLOB-ANT) for the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service simulations of air quality forecasts and reanalyses. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2261–2279 (2024).

Huo, D. et al. Carbon Monitor Cities near-real-time daily estimates of CO2 emissions from 1500 cities worldwide. Sci. Data 9, 533 (2022).

Biswal, A. et al. Spatially resolved hourly traffic emission over megacity Delhi using advanced traffic flow data. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 661–680 (2023).

Mittakola, R. T. et al. High-resolution gridded CO2 and pollutant emission data from road traffic in Indian cities. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28330067.v2 (2025).

COPERT | Calculations of Emissions from Road Transport. https://copert.emisia.com/ (2024).

NEXQT | city decarbonization platform. NEXQT. https://www.nexqt.com (2024).

Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) Disaster Management (MCGM). https://dm.mcgm.gov.in/ward-maps (2023).

LightGBM 4.5.0 documentation, Microsoft Corporation. https://lightgbm.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ (2025).

Ke, G. et al. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. in Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 3149–3157 (Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017).

Chicco, D., Warrens, M. J. & Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, e623 (2021).

Mittakola, R. T., Ciais, P. & Zhou, C. Short-to-medium range forecast of natural gas use in the United States residential buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 437, 140687 (2024).

Lundberg, S. shap: A game theoretic approach to explain the output of any machine learning model.

Bonnemaizon, X. et al. Scaling traffic variables from sensors sample to the entire city at high spatiotemporal resolution with machine learning: applications to the Paris megacity. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 4, 035010 (2024).

Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell | Government of India. https://ppac.gov.in/ (2024).

Global Human Settlement - GHSL Homepage - European Commission. https://human-settlement.emergency.copernicus.eu/ (2020).

Open Government Data (OGD) Platform India. https://data.gov.in (2022).

Parivahan Sewa | Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India. https://parivahan.gov.in/parivahan//en (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quart J Roy Meteor Soc 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Road Traffic Management. TomTom https://www.tomtom.com/solutions/road-traffic-management/ (2025).

Functional Urban Areas. OECD https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/oecd-definition-of-cities-and-functional-urban-areas.html (2019).

European Commission, J. R. C. GHS-FUA R2019A - GHS functional urban areas, derived from GHS-UCDB R2019A, (2015), R2019A. European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC) https://doi.org/10.2905/347F0337-F2DA-4592-87B3-E25975EC2C95 (2019).

Containment Framework, Ministry of Home Affairs. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHAOrder_29042021.pdf (2021).

Lekaki, D. et al. Road transport emissions in EDGAR (Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research). Atmos. Environ. 324, 120422 (2024).

VAHAN SEWA| Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India. https://vahan.parivahan.gov.in/vahan4dashboard/ (2021).

India traffic report | TomTom Traffic Index. India traffic report | TomTom Traffic Index https://www.tomtom.com/traffic-index/india-country-traffic/ (2025).

Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/ceds (2024).

Guevara, M. et al. Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service TEMPOral profiles (CAMS-TEMPO): global and European emission temporal profile maps for atmospheric chemistry modelling. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 367–404 (2021).

Shi, Q. et al. High spatiotemporal resolution traffic CO2 emission maps derived from Floating Car Data (FCD) for 20 European cities (2023). Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 1–24, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2025-458 (2025).

Bonnemaizon, X. et al. Harmonized Annual Averaged Traffic Data at Street Segment Level for European Cities. Sci. Data 12, 1365 (2025).

Peshin, T., Sengupta, S. & Azevedo, I. M. L. Should India Move toward Vehicle Electrification? Assessing Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas and Criteria Air Pollutant Emissions of Alternative and Conventional Fuel Vehicles in India. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9569–9582 (2022).

Acknowledgements

CHETNA-Road is part of a larger CHETNA project (City-wise High-resolution carbon Emissions Tracking and Nationwide Analysis), which leverages artificial intelligence and advanced datasets to deliver high-resolution, near real-time daily CO2 and air pollutant emissions data for over 100 Indian cities. The CHETNA project is fully funded by the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed the study: R.M., P.C., C.Z., M.B., H.P. Developed code for data processing, machine learning models: R.M. Performed the analysis: R.M., P.C., C.Z., M.B. Tested the relevancy of dataset: Q.S., X.B., N.M., C.Z., H.P. Writing—original draft: R.M. Writing— review & editing: All co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mittakola, R.T., Ciais, P., Barthelemy, M. et al. High-resolution gridded CO2 and pollutant emission data from road traffic in Indian cities. Sci Data 12, 1986 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06287-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06287-9