Abstract

Cold seeps are unique and important deep-sea ecosystems characterized by chemosynthesis. The deep-sea limpet Bathyacmaea lactea is an endemic and ecologically important species inhabiting these extreme environments, representing an ideal model for studying adaptation and evolution in cold seeps. To provide a high-quality genomic resource for this purpose, we therefore report a high-quality chromosome-level genome for B. lactea, combining PacBio, Illumina, and high-resolution chromosome conformation capture techniques. The assembly spans 769.80 Mb, with contig and scaffold N50 values of 1.27 Mb and 82.05 Mb, respectively, and ultimately yielded 10 chromosome sequences. BUSCO assessment revealed a completeness score of 96.90%, indicating a high-quality genome assembly. Gene annotations showed a high level of accuracy and completeness, with 21,122 predicted protein-coding genes. As the first chromosome-level genome of the deep-sea limpet, it complements a previously reported contig-level assembly. By anchoring the genome to the chromosome level, this assembly offers a more complete and structured genomic resource, facilitating future studies on the evolution and adaptation of cold-seep animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The deep sea, an integral but underexplored part of the marine ecosystem characterized by darkness, high pressure, hypoxia, low temperatures, and limited food, was once considered barren1,2. However, recent technological advances in deep-sea exploration have revealed an unexpected abundance and rich diversity of animals inhabiting this extreme environment, with over 600 invertebrate species reported in hydrothermal vents and cold seeps alone, dominated by molluscs (e.g., mussels, limpets, snails) and crustaceans (e.g., shrimps)3,4,5. These very extremes make the deep sea an unparalleled natural laboratory for probing the limits of life, origins, and genomic adaptations. Despite these discoveries, how animals evolved and adapted to these harsh conditions remains a major and poorly understood question. Genomic analysis provides the foundation for understanding these key questions. Chromosome-level assemblies are therefore indispensable, as they enable the identification of large-scale rearrangements, conserved synteny and the organization of regulatory elements that shape genome structure and evolution, which cannot be resolved from contig-level data6. The advent of high-throughput sequencing has now ushered deep-sea biology into the genomics era7,8,9,10, with chromosome-level assemblies enabling the dissection of adaptive mechanisms across multiple genomic levels11,12,13.

Molluscs, the second largest and evolutionarily successful animal group surviving multiple mass extinctions since the Cambrian, exhibit superb adaptations across diverse environments. While genomic and transcriptomic analyses have enhanced our understanding of their molecular adaptations, most studies focus on shallow-water species14,15,16,17,18. Recent genomic studies of deep-sea molluscs have begun to reveal critical mechanisms of adaptation, providing deeper insights into the genetic basis behind survival in extreme deep-sea environments7,11,19,20. Limpets (Patellogastropoda), belonging to one of the most primitive gastropod lineages and serving as emerging evolutionary models, are particularly valuable for such studies21,22,23. The existing contig-level genome assembly of the deep-sea limpet B. lactea reveals adaptive signatures through expanded gene families and rapidly evolving genes associated with heterocyclic compound metabolism, membrane-bounded organelle, metal ion binding, and nitrogen and phosphorus metabolism, illuminating molecular adaptations to cold seeps24. However, the current lack of chromosome-level genomic resources for deep-sea limpets impedes essential analyses such as synteny-based phylogenomics, adaptive structural variant detection, and chromatin topology mapping, which are critical for fully deciphering the genetic basis of extreme environment colonization.

In this study, we constructed a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly for B. lactea using PacBio long reads and Hi-C sequencing data. The genome assembly spans 769.80 Mb, achieving a scaffold N50 length of 82.05 Mb, which represents a significant improvement over the previously reported contig-level genome assembly with a contig N50 of 1.57 Mb24. Of the total assembly, 95.22% was anchored to 10 chromosomes. With a BUSCO completeness score of 96.90%, the new assembly demonstrates a significant improvement. In summary, this high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly will serve as a valuable resource for future studies on the adaptation and evolution of animals in cold seeps.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

B. lactea specimens were collected in the South China Sea (22.10°N, 119.28°E, 1,168 m depth) by the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) of Kexue. Tissues were frozen with liquid nitrogen and then kept at −80 °C until further use.

We applied the k-mer-based method to estimate genome size of B. lactea25. Firstly, a paired-end sequencing library with an insert size of 350 bp was constructed and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform. A total of 36.95 Gb short-read sequencing data were generated (Table 1). Secondly, we selected the PacBio platform to generate long genomic reads for the construction of B. lactea reference genome. A total of 105.13 Gb data were generated with a mean length of 9.00 kb. Thirdly, we applied Hi-C sequencing technologies to generate a chromosome-level genome. For the Hi-C library, formaldehyde was used to crosslink cells, and DpnII restriction enzyme was employed to digest the DNA. The DNA was then labeled and processed through terminal repair. The Hi-C library was constructed using the Dovetail Omni-C Kit (Cantata Bio, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quality control of the library was performed using Qubit 2.0, the Agilent 2100 system, and qPCR methods. Hi-C sequencing was carried out on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, USA). The resulting sequencing data were incorporated into the genome assembly process and are summarized in Table 1.

Genome assembly and Hi-C scaffolding

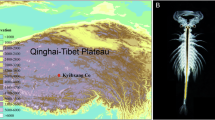

The genome was assembled using Canu version 2.226 with optimized parameters for eukaryotic genomes (genomeSize = 792.9 m) with PacBio long-read data. The assembly was further polished using Pilon v1.2327 (--fix snps,indels) with Illumina short-read data. Duplicate sequences were removed using Purge_dups v1.2.528 with cutoff parameters automatically estimated from the read depth histogram. For Hi-C scaffolding, Juicer v1.629 (-s DpnII -y /path/to/DpnII.txt) was initially used to process the Hi-C sequencing data. Next, 3D-DNA v20100830 was employed to scaffold the contigs using default settings. Juicebox v1.11.0829 was then used to visualize the chromosome assembly, select the best result from the 3D-DNA output, and refine the chromosome boundaries based on the interaction heatmap. Finally, we reran 3D-DNA with the corrected assembly and exported the final chromosome-level genome. After Hi-C scaffolding, 95.22% of the assembled sequences were successfully anchored to 10 chromosomes. The 10 chromosomes were clearly displayed in the interaction heatmap (Fig. 1b). All bioinformatic tools used in this section were applied with default parameters.

Chromosome-level genome assembly of B. lactea. (a) Genome overview of the 10 chromosomes. Tracks from inner to outer represent assembled chromosomes, GC skew (heatmap with significance bars showing GC preference), GC content, and gene density, respectively, with densities calculated within a 100-kb window. (b) Hi-C interaction heatmap of the B. lactea genome. Color blocks indicate interaction intensity from yellow (low) to red (high).

Repeat annotation

We used RepeatModeler2 v2.0.131 with default parameters to build a de novo repeat library. LTR_FINDER v1.0732 (-D 15000 -d 1000 -L 7000 -l 100 -p 20) and LTR_retriever v2.9.033 were used to identify long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences in the genome by using default parameters. Repeats in the B. lactea genome were identified using RepeatMasker v4.134 (-e rmblast -xsmall -s -a), incorporating RepBase database, the LTR library and a species-specific de novo library. The proportion of transposon elements (TEs) in the B. lactea genome is 43.68%. Among them, retroelement accounts for 25.68%, DNA transposon accounts for 16.74% (Table 2).

Gene prediction and annotation

Protein-coding genes were predicted using three approaches: ab initio prediction, homology-based prediction, and transcript-based prediction. Ab initio prediction was carried out with Braker2 v2.1.635 (--round 2). For homology-based prediction, protein sequences from 8 species—Homo sapiens (GCF_000001405.40)36, Nematostella vectensis (GCF_932526225.1)37, Drosophila melanogaster (GCF_000001215.4)38, P. yessoensis (GCF_002113885.1)17, Haliotis discus (GCA_044707095.1)39, Elysia chlorotica (GCA_003991915.1)40, P. canaliculata (GCF_003073045.1)41, and Lottia gigantea (GCF_000327385.1)42 were retrieved from the NCBI database and used in TblastN v2.13.043 with an e-value ≤ 1e-5. For transcript-based annotation, clean RNA-seq reads were aligned to the B. lactea genome assembly using HISAT2 v2.2.144, and the gene set was predicted using PASA v2.5.245 (-C -R --ALIGNERS blat,gmap). The results from these three methods were integrated with EvidenceModeler v1.1.146 (--segmentSize 100000 --overlapSize 10000) to generate a final, non-redundant gene set. A total of 21,122 protein-coding genes were annotated for the B. lactea genome.

Functional annotation of the predicted protein-coding genes was conducted using six public databases: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), NCBI-NR (non-redundant protein database), Swiss-Prot, SMART, and InterProScan. BLASTP v2.2.2347 was used with an e-value cutoff of 1e-5. The results indicated that 20,387 (96.50%) of the predicted genes were successfully annotated by at least one of the public databases (Table 3).

Noncoding RNAs were annotated using tRNAscan‐SE48 and the Rfam database49 based on Infernal50. The non-coding RNA statistics are summarized in Table 4.

Data Records

The raw sequencing data of B. lactea have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA1237989 with accession number SRP57168351. The final genome assembly is available in the ENA under accession number GCA_977020065.152. In addition, the genome assembly data and annotations have also been deposited in Figshare53.

Technical Validation

Evaluation of the genome assembly

The genome size of B. lactea was estimated to be approximately 792.90 Mb based on 19-mer frequency distribution analysis. This estimate aligns with the final genome assembly size of 769.80 Mb (Table 1). The assembly produced 10 chromosomes, which is consistent with previous karyotyping studies of shallow limpets, including species from the Patelloidea superfamily54,55.

To evaluate the accuracy of the B. lactea genome assembly, we assessed its completeness using the “metazoan_odb10” database from BUSCO v556. The BUSCO completeness of the genome was 96.9% (C: 96.9%, S: 95.5%, D: 1.4%, F: 1.5%, M: 1.6%, n: 954) (Table 5). Additionally, Illumina short reads used for the genome survey were aligned to the B. lactea assembly using Bowtie2 v2.4.557, with 98.20% of the reads successfully mapped to the genome. These results collectively confirm the high quality of the genome assembly.

Gene annotation validation

To assess the completeness of the annotated gene set, we conducted BUSCO analysis using the “metazoan_odb10” database. The analysis showed that 87.60% of the conserved single-copy orthologs were complete (86.70% single-copy genes and 0.90% duplicated genes), 4.70% were fragmented, and 7.70% were missing (Table 5). Additionally, functional annotation indicated that 96.50% of the predicted genes were annotated by at least one public database (Table 3).

Data availability

In this study, sequencing data for B. lactea, including PacBio, Illumina, Hi-C, and transcriptome sequencing, have been deposited in the ENA under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1237989. The raw sequencing reads are available under the accession number SRP57168351, and the final genome assembly under GCA_977020065.152. In addition, the genome assembly data and annotations have also been deposited at Figshare53.

Code availability

No specific code was used in this study. All commands and pipelines used in the data processing were performed according to manuals and protocols of corresponding bioinformatics software, with parameters described in the Methods section. If no detailed parameters were mentioned for a software, default parameters were used.

References

Danovaro, R., Snelgrove, P. V. & Tyler, P. Challenging the paradigms of deep-sea ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 465–475, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.06.002 (2014).

Xiao, X., Wang, J. & Ding, K. MEER: Extraordinary flourishing ecosystem in the deepest ocean. Cell 188, 1175–1177, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.12.037 (2014).

Van Dover, C. L., German, C. R., Speer, K. G., Parson, L. M. & Vrijenhoek, R. C. Evolution and biogeography of deep-sea vent and seep invertebrates. Science 295, 1253–1257, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067361 (2002).

Levin, L. A. Ecology of cold seep sediments: interactions of fauna with flow, chemistry and microbes. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420037449-3 (CRC Press, 2005).

Gage, J. & Tyler, P. Deep-sea biology: a natural history of organisms at the deep-sea floor. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400070156 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1999).

Rhie, A. et al. Towards complete and error-free genome assemblies of all vertebrate species. Nature 592, 737–746, https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.22.110833 (2021).

Sun, J. et al. Adaptation to deep-sea chemosynthetic environments as revealed by mussel genomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0121, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0121 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Genomic adaptations to chemosymbiosis in the deep-sea seep-dwelling tubeworm Lamellibrachia luymesi. BMC Biol. 17, 91, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-019-0713-x (2019).

Steffen, K. et al. Whole genome sequence of the deep-sea sponge Geodia barretti (Metazoa, Porifera, Demospongiae). G3-GENES GENOM GENET 13, jkad192, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkad192 (2023).

Mu, Y. et al. Whole genome sequencing of a snailfish from the Yap Trench (~7,000 m) clarifies the molecular mechanisms underlying adaptation to the deep sea. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009530, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1009530 (2021).

Lan, Y. et al. Hologenome analysis reveals dual symbiosis in the deep-sea hydrothermal vent snail Gigantopelta aegis. Nat. Commun 12, 1165, https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-021-21450-7 (2021).

He, X. et al. Genomic analysis of a scale worm provides insights into its adaptation to deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Genome Biol. Evol. 15, evad125, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evad125 (2023).

Xu, W. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of hadal snailfish reveals mechanisms of deep-sea adaptation in vertebrates. eLife 12, RP87198, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.87198 (2023).

Zheng, P. et al. Insights into deep‐sea adaptations and host-symbiont interactions: A comparative transcriptome study on Bathymodiolus mussels and their coastal relatives. Mol. Ecol. 26, 5133–5148, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14160 (2017).

Takeuchi, T. et al. Bivalve-specific gene expansion in the pearl oyster genome: implications of adaptation to a sessile lifestyle. ZOOL LETT 2, 3, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-016-0039-2 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Scallop genome reveals molecular adaptations to semi-sessile life and neurotoxins. Nat. Commun 8, 1721, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01927-0 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Scallop genome provides insights into evolution of bilaterian karyotype and development. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0120, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0120 (2017).

Simakov, O. et al. Insights into bilaterian evolution from three spiralian genomes. Nature 493, 526–531, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11696 (2013).

Sun, J. et al. The Scaly-foot snail genome and implications for the origins of biomineralised armour. Nat. Commun 11, 1657, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15522-3 (2020).

Ip, J. C.-H. et al. Host–endosymbiont genome integration in a deep-sea chemosymbiotic clam. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 502–518, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa241 (2020).

Colgan, D. J., Ponder, W. F. & Eggler, P. E. Gastropod evolutionary rates and phylogenetic relationships assessed using partial 28S rDNA and histone H3 sequences. Zool. Scr. 29, 29–63, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1463-6409.2000.00021.x (2000).

Nakano, T. & Ozawa, T. Worldwide phylogeography of limpets of the order Patellogastropoda: molecular, morphological and palaeontological evidence. J. Molluscan Stud. 73, 79–99, https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eym001 (2007).

Pagel, M. Limpets break Dollo’ s Law. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 278–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.020 (2004).

Liu, R. et al. De Novo genome assembly of limpet Bathyacmaea lactea (Gastropoda: Pectinodontidae): the first reference genome of a deep-sea gastropod endemic to cold seeps. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, 905–910, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evaa100 (2020).

Sun, H., Ding, J., Piednoël, M. & Schneeberger, K. findGSE: estimating genome size variation within human and Arabidopsis using k-mer frequencies. Bioinformatics 34, 550–557, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx637 (2020).

Koren, S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.215087.116 (2017).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9, e112963, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3327 (2016).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. PNAS 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2018).

Chen, N. Using Repeat Masker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc 5, 4–10, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2004).

Bruna, T., Hoff, K., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M. & Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR GENOM BIOINFORM 3(1), 1108, https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaa108 (2021).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_000001405.29 (2022).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_932526225.1 (2022).

Hoskins, R. A. et al. The Release 6 reference sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 25, 445–458, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.185579.114 (2015).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_044707095.1 (2024).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_003991915.1 (2019).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_003073045.1 (2018).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_000327385.1 (2012).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (1990).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Kent, W. J. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.229202 (2002).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab688 (2002).

Ontiveros-Palacios, N. et al. Rfam 15: RNA families database in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D258–D267, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1023 (2025).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/insdc.sra:SRP571683 (2025).

European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/insdc.gca:GCA_977020065.1 (2025).

Chen, D. Deep-sea limpet (Bathyacmaea lactea) genome. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28928334 (2025).

Hawkins, S. J. et al. The genome sequence of the common limpet, Patella vulgata (Linnaeus, 1758). Wellcome Open Res. 8, 418, https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.20008.1 (2023).

Lawniczak, M. K. et al. The genome sequence of the blue-rayed limpet, Patella pellucida Linnaeus, 1758. Wellcome Open Res. 7, 126, https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17825.1 (2022).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Langdon, W. B. Performance of genetic programming optimised Bowtie2 on genome comparison and analytic testing (GCAT) benchmarks. BioData Min. 8, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13040-014-0034-0 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was commissioned by the Ocean + Consortium for discipline breakthrough and supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [32222085], Science & Technology Innovation Project of Laoshan Laboratory [LSKJ202202804], National Key R&D Program of China [2024YFC2816000], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [842341005]. We acknowledge the support of the High-Performance Biological Supercomputing Center at the Ocean University of China for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Yuli Li. Project coordination and supervision: Yuli Li, Shi Wang. Genome assembly and bioinformatics analysis: Dongsheng Chen, Yuanting Ma. DNA extraction and sample preparation: Yaran Liu. Manuscript revision and critical feedback: Yuli Li, Shi Wang, Minxiao Wang, Jing Wang. Manuscript drafting and editing: Dongsheng Chen, Yuanting Ma.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Ma, Y., Liu, Y. et al. An improved chromosome-level genome assembly of a deep-sea limpet (Bathyacmaea lactea). Sci Data 12, 2039 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06329-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06329-2