Abstract

The ancient Tibetan sheep breed has been shaped by long-term natural selection and artificial breeding in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau region. Although their green organic mutton is highly favored by consumers, the low production efficiency of Tibetan sheep has resulted in a persistent supply shortage. Whole-genome sequencing analysis can identify genetic markers and candidate genes associated with important economic traits, which can be used in genomic-assisted breeding to accelerate genetic improvement and increase production efficiency. Here, we report whole-genome sequencing data from 220 Tibetan sheep across 11 populations inhabiting different altitudes, with an average coverage of 6.20X. Over 98.34% of clean reads were successfully mapped to the Tibetan sheep reference genome, identifying approximately 21.10 million high-quality single-nucleotide polymorphisms. This dataset provides a valuable resource for studying the genetic diversity and adaptability of Tibetan sheep, and may accelerate improvements in genetic traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

As one of the three major primitive sheep breeds in China, Tibetan sheep (Ovis aries) have lived on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau for thousands of years, uniquely adapted to its high-altitude, cold, and strong ultraviolet conditions. Their excellent survival traits also include coarse feed tolerance, strong disease resistance, and robust foraging ability. The Tibetan sheep breed, shaped by long-term natural selection and artificial breeding, serves as a vital livelihood resource for local farmers and herders, and contributes to the sustainable growth and high-quality development of the pastoral economy.

Sheep, which are among the earliest domesticated animals, have maintained a close relationship with humans, especially nomadic people. Research indicates that Tibetan sheep originated from ancient northern Chinese sheep around 3,100 years ago1, diverging approximately 2,000‒2,600 years ago2. A small group of Tibetan sheep continued to expand southwestward, reaching central Tibet about 1,300 years ago1, while the remaining populations settled across various regions of Qinghai, gradually adapting to local geographical conditions and evolving into distinct breeds. Statistics show that China’s Tibetan sheep population stands at 32.5 million head, accounting for 11% of the total sheep population3,4. However, because of environmental constraints, the Tibetan breed has long been trapped in a cycle of low-level development and low-efficiency production. Despite the publication of the Tibetan sheep genome sequence5,6, most research remains focused on high-altitude adaptability, mutton quality, and nutrient metabolism7,8,9. Omics technologies have revealed that significant convergent evolution of the EPAS1 and EGLN1 genes has contributed to the breed’s adaptability to high-altitude environments, along with the identification of additional novel adaptive genes10,11,12. Plateau adaptability is a complex, polygenic trait13,14,15, with distinct local adaptation mechanisms observed among different Tibetan sheep populations and subtypes inhabiting varying altitudes. Furthermore, the lack of phenotypic and genomic data has hindered efforts to improve key economic traits in Tibetan sheep through genetic improvement. To bridge productivity gaps and accelerate breeding progress, it is imperative that we elucidate the genetic mechanisms underlying the formation of important economic traits in these sheep.

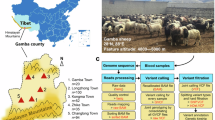

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has become a standard tool in livestock genetic breeding research, enabling the detection of genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions and deletions (InDels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variations (SVs). This approach enables the identification of causal variations related to growth, reproduction, adaptability, and disease resistance. Here, we provide WGS data from 220 Tibetan sheep across 11 populations spanning an altitudinal gradient of 2,887 m to 4,643 m, marking the most comprehensive collection of whole-genome sequences from this breed to date. After aligning the sequencing data with the Tibetan sheep reference genome, a total of 21,099,381 high-quality SNPs were identified. We anticipate that this dataset will play an important role in assessing genetic diversity, gene flow, and regions of positive selection, as well as identifying candidate genes associated with economic traits in the Tibetan sheep population.

Methods

Sample collection

All animal experiments were performed under the guidance of ethical regulations from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Lanzhou Institute of Husbandry and Pharmaceutical Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Approval No. NKMYD201805; Approval Date: 18 October 2018). For this WGS analysis, we selected 11 Tibetan sheep populations that are grazed year-round in different agroclimatic zones, representing the diverse environments of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (Table 1). Twenty unrelated adult samples were collected from each population, with 5 mL of blood drawn from the jugular vein before morning grazing and stored in EDTA tubes at −20 °C.

DNA extraction and quality control

The blood samples were thawed at room temperature for 30 min, and genomic DNA was extracted using a blood genomic DNA extraction kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Agarose gel (1%) electrophoresis was used to detect DNA degradation and contamination in the samples. DNA purity was assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and DNA concentrations were determined using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Qualifying DNA samples were sent to Guangzhou GeneDenovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) for WGS.

Library preparation and sequencing

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, sequencing libraries for all samples were generated using the library construction kit from Illumina (CA, USA). Appropriate amounts of DNA were enzymatically fragmented into short segments, end-repaired, and dA-tailed prior to ligation of sequencing adapters. The DNA fragments were purified using AMPure XP beads (Merck, Shanghai, China), and fragments in the range of 300–400 bp were selected for PCR amplification. The size and concentration of the libraries were measured using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, CA, USA). The effective concentration of each library was accurately quantified using the Bio-RAD CFX 96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Libraries that passed quality control were sequenced on the Hiseq X10 PE150 platform (Illumina, CA, USA).

Sequence data pre-processing and mapping

Raw image data obtained from sequencing were converted into raw sequencing reads through base calling, and the results were stored in FASTQ file format. The fastp software (v0.23.4) was used for quality control of the sequencing data, including filtering low-quality reads, trimming low-quality bases from the 3’ end, and removing adapter sequences. Additionally, statistics on quality score distribution, GC content, error rate distribution, and N content were generated.

High-quality filtered reads were aligned to the Tibetan sheep reference genome (GCA_017524585.1) using the BWA-MEM algorithm (v0.7.17-r1188). The resulting Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files were sorted using Samtools (v1.17), and PCR duplicate reads were marked using the MarkDuplicates module in the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v4.5.0.0).

Variant calling, filtering and annotation

As shown in Fig. 1, variant calling and filtering were performed using GATK (v4.5.0.0). For SNP calling, Genomic Variant Call Format (GVCF) files were generated using the HaplotypeCaller module with the “-ERC GVCF” option. To improve scalability and accelerate joint genotyping, GVCF files were consolidated into a GenomicsDB datastore. Next, the GenotypeGVCFs module was applied to joint calling to produce population-based Variant Call Format (VCF) files. Biallelic SNPs were obtained using the SelectVariants module with the “-select-type SNP” and “–restrict-alleles-to BIALLELIC” parameters. To reduce false-positive SNPs, we applied the VariantFiltration module with the following quality control parameters:–filter-name “QD_filter” -filter “QD < 2.0”;–filter-name “FS_filter” -filter “FS > 60.0”;–filter-name “MQ_filter” -filter “MQ < 40.0”;–filter-name “SOR_filter” -filter “SOR > 3.0”;–filter-name “MQRankSum_filter” -filter; “MQRankSum < −12.5”;–filter-name “ReadPosRankSum_filter” -filter “ReadPosRankSum < −8.0”; and–cluster-size 3–missing-values-evaluate-as-failing. Additional SNP filtering was performed using PLINK (v1.9) with the following three criteria: SNP call rate < 0.1; minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01; and only SNPs on autosomes were retained. Remaining SNPs were annotated based on genomic position using ANNOVAR.

SNP validation

To assess the accuracy of identified SNPs, variants were compared against public datasets from the Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP; https://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/snp/organisms/archive/sheep_9940/VCF/) and the iSheep database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/isheep/download). To convert physical coordinates from these public datasets were to the reference genome used in this study, we employed the LiftOver tool from the University of California Santa Cruz16. The overlap between the variants identified in this study and public datasets was then calculated to determine the proportion of newly discovered SNPs.

Data Records

Whole-genome sequence data (FASTQ format) from 220 Tibetan Sheep samples representing 11 populations analyzed herein have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and have been assigned BioProject accession number PRJNA1138910 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRP527227)17. The final VCF files have been deposited in the European Variation Archive (EVA) under accession number PRJEB10094218.

Technical Validation

Quality control of sequencing data

Quality control of raw WGS data is the foundation for ensuring accuracy and reliability in downstream analysis19. For each individual, we obtained 13.78–24.29 Gb of sequenced bases (average: 16.75 Gb), with 85.32%–94.27% (average: 91.86%) of the bases having a Phred scaled quality score of 30 (Fig. 2, Table 2). The genome coverage ranged from 5.10X to 9.00X (average: 6.20X). To comprehensively identify genetic variations, increasing the sequencing depth can be used to improve genome coverage and variant detection rates. High-depth resequencing (30X) is considered the “gold standard”20. However, if funding is limited, sequencing fewer samples at high depth may not provide adequate detection of all genetic variations19,21. Indeed, a WGS study of pigs found that sequencing depths below 4X resulted in more false-positive variants, indicating that 4X is the lower limit for sequencing quality22. In this study, the average sequencing depth was 6.20X, which is above the 4X threshold. Additionally, with low-depth sequencing, a larger sample size reduces the false-positive rate in variant detection23; thus, our sample size of 220 individuals was considered sufficient to accurately identify genetic variations in the Tibetan sheep genome. Although high-depth sequencing can yield more information, recent studies suggest that low-depth sequencing is a more effective approach for large sheep populations24,25,26.

Fastp enables rapid data preprocessing and quality control of high-throughput sequencing data27. As shown in Fig. 3, MultiQC was used to integrate fastp results and generate quality reports. The duplicate read rate serves as an indicator of the quality of sequencing data, with lower rates indicating better data quality. In this study, the average duplicate read rate was 22.84% and the average unique read rate was 77.16% (Fig. 3A). However, distinct peaks were observed in certain regions of some individual samples, possibly attributable to PCR over-amplification during sequencing28. Figure 3B shows the average quality score for each base position, which was maintained at ~35, indicating very high sequencing quality. Similarly, the per-sequence quality score was consistently ~35, further demonstrating the high quality of the sequencing data (Fig. 3C). The GC content across all samples showed a stable distribution (average: 44.60%, Fig. 3D), suggesting no exogenous genome contamination during sequencing29.

Quality control of SNP data

Using the HaplotypeCaller function in GATK30, a total of 235,803,940 raw SNPs were identified in the 11 Tibetan sheep populations. To exclude low-quality SNPs, we used the VariantFiltration function in GATK, resulting in 213,867,729 SNPs. Finally, SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.05 and a missing rate > 10% were removed, totalling 21,099,381 SNPs for subsequent analyses. As shown in Fig. 4, we identified ~4.58 million SNPs (21.704%) that have not been reported previously in the dbSNP (https://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/snp/organisms/archive/sheep_9940/VCF/) and the iSheep Data (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/isheep/download), which could be due to prior underrepresentation of the sheep breeds studied here. Analysis of SNPs counts by mutation types across populations showed the G:C → A:T mutation to be the most prevalent (Fig. 5).

Variant detection accuracy can be assessed by the ratio of transitions (Ti) to transversions (Tv)31,32. In the absence of selection pressure, Ti/Tv is expected to be 0.5; however, this is rarely observed. A typical Ti/Tv ratio for whole-genome analysis is ~2.0–2.1, while novel variants generally show a ratio of ~1.5. In this study, the observed Ti/Tv ratio was 2.56, suggesting high SNP calling accuracy; ratios exceeding 4 may indicate artifacts33.

In the quality control of genomic data, the heterozygous-to-homozygous (Het/Hom) ratio is used to assess the genetic diversity of samples. Under the assumption of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, the expected Het/Hom ratio in human genomic data is 2.029. In this study, the Het/Hom ratio was 0.92, possibly reflecting inbreeding in Tibetan sheep, which can increase the likelihood of homozygosity. Additionally, a genomic evaluation of inbreeding coefficients in the 11 populations revealed severe inbreeding in some34, further demonstrating the high sequence quality in this study.

The SNP density can reflect both the genetic diversity of samples and the distribution of variations in the genome. In this study, there was an average of one SNP every 125.62 bp, with the highest densities observed on the sex chromosomes and more uniform distribution on the autosomes (Table 3). To understand the functions of these SNPs, annotation was performed using the ANNOVAR software35. Most SNPs were found to be distributed in intronic and intergenic regions (Table 4).

Polymorphism information content (PIC) is an indicator used to measure the polymorphism of genetic markers, reflecting the diversity of alleles at a locus. Our analysis showed the highest PIC value in the Tao sheep (TS) group and the lowest in the Zashijia sheep (ZSJ) group. (Fig. 5). Nucleotide diversity (π) is an indicator used to measure the degree of nucleotide variation, reflecting the average number of nucleotide substitutions in a population. In our analysis, the Tianjun white Tibetan sheep (WT) group had the highest π value, while the Zashijia sheep (ZSJ) group had the lowest (Fig. 6).

Data availability

Sequencing data was uploaded to SRA under accession number SRP527227 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRP527227). The identified variants data were deposited in the EVA under accession number PRJEB100942.

Code availability

The list of the software and parameters used in this study is available through GitHub (https://github.com/luzengkui/sheep_NGS_01).

References

Hu, X. J. et al. The genome landscape of Tibetan sheep reveals adaptive introgression from argali and the history of early human settlements on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Mol Biol Evol. 36, 283–303 (2019).

Zhao, Y. X. et al. Genomic reconstruction of the history of native sheep reveals the peopling patterns of nomads and the expansion of early pastoralism in East Asia. Mol Biol Evol. 34, 2380–2395 (2017).

China National Commission of Animal Genetic Resources. Animal genetic resources in China (sheep and goats). (China Agriculture Press, 2011).

Li, X. et al. Whole-genome resequencing to investigate the genetic diversity and mechanisms of plateau adaptation in Tibetan sheep. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 15, 164 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_017524585.1 (2021).

Lu, Z. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Guide Black-Fur sheep (Ovis aries). Sci Data. 11, 711 (2024).

Han, B. et al. Multiomics analyses provide new insight into genetic variation of reproductive adaptability in Tibetan sheep. Mol Biol Evol. 41, msae058 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Insight into the differences in meat quality among three breeds of sheep on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau from the perspective of metabolomics and rumen microbiota. Food Chem X. 23, 101731 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Effects of different feeding regimes on muscle metabolism and its association with meat quality of Tibetan sheep. Food Chem. 374, 131611 (2022).

Wu, D. et al. Convergent genomic signatures of high-altitude adaptation among domestic mammals. Natl Sci Rev. 7, 952–963 (2020).

Jin, M. et al. Whole-genome resequencing of Chinese indigenous sheep provides insight into the genetic basis underlying climate adaptation. Genet Sel Evol. 56, 26 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Multi-omic analyses shed light on the genetic control of high-altitude adaptation in sheep. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 22, qzae030 (2024).

Wen, J. et al. Ancestral origins and post-admixture adaptive evolution of highland Tajiks. Natl Sci Rev. 11, nwae284 (2024).

Ping, J. et al. A highland-adaptation variant near MCUR1 reduces its transcription and attenuates erythrogenesis in Tibetans. Cell Genom. 5, 100782 (2025).

Ferraretti, G. et al. Convergent evolution of complex adaptive traits modulates angiogenesis in high-altitude Andean and Himalayan human populations. Commun Biol. 8, 377 (2025).

Kuhn, R. M. et al. The UCSC genome browser database: update 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D668–673 (2007).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP527227 (2024).

ENA European Variation Archive https://identifiers.org/ena.embl:ERP182370 (2025).

Pfeifer, S. P. From next-generation resequencing reads to a high-quality variant data set. Heredity 118, 111–124 (2017).

Sims, D. et al. Sequencing depth and coverage: key considerations in genomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 121–132 (2014).

Ayalew, W. et al. Whole genome sequences of 70 indigenous Ethiopian cattle. Sci Data. 11, 584 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Optimal sequencing depth design for whole genome re-sequencing in pigs. BMC Bioinformatics 20, 556 (2019).

Le, S. Q. & Durbin, R. SNP detection and genotyping from low-coverage sequencing data on multiple diploid samples. Genome Res. 21, 952–960 (2011).

Zhao, L. et al. Whole-genome resequencing of Hu sheep identifies candidate genes associated with agronomic traits. J Genet Genomics. 51, 866–876 (2024).

Zhao, F. et al. Analysis of 206 whole-genome resequencing reveals selection signatures associated with breed-specific traits in Hu sheep. Evol Appl. 17, e13697 (2024).

Jin, M. et al. Genomic insights into the population history of fat-tailed sheep and identification of two mutations that contribute to fat tail adipogenesis. J Adv Res. S2090-1232, 00304–2 (2025).

Chen, S. et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Belay, S. et al. Whole-genome resource sequences of 57 indigenous Ethiopian goats. Sci Data. 11, 139 (2024).

Guo, Y. et al. Three-stage quality control strategies for DNA re-sequencing data. Brief Bioinform. 15, 879–889 (2014).

DePristo, M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

Gheyas, A. et al. Whole genome sequences of 234 indigenous African chickens from Ethiopia. Sci Data. 9, 53 (2022).

Rabbani, M. A. G. et al. Whole genome sequencing of three native chicken varieties (Common Deshi, Hilly and Naked Neck) of Bangladesh. Sci Data. 11, 1432 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Genome measures used for quality control are dependent on gene function and ancestry. Bioinformatics. 31, 318–323 (2015).

Sun, L. et al. The accumulation of harmful genes within the ROH hotspot regions of the Tibetan sheep genome does not lead to genetic load. BMC Genomics. 26, 60 (2025).

Wang, K. et al. Annovar: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Plan (25JRRA453), the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (1610322024012), the Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (25-LZIHPS-07), the Key R&D Program in Gansu Province (24YFNA022), and the Modern China Wool Cashmere Technology Research System (CARS-39-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. and J.L. conceived this study. Z.L. and C.Y. collected the samples and performed the experiments; Z.L., C.Y., T.G., F.W. and B.C. performed the research and analyzed the data. Z.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Z., Yuan, C., Guo, T. et al. Whole-genome variant of 220 Tibetan sheep from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci Data 13, 61 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06360-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06360-3