Abstract

Flemingia macrophylla, a perennial shrub of the family Fabaceae, possesses pharmacological properties such as anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities. However, its whole genome has remained largely unexplored. In this study, we generated a chromosome-level genome assembly of F. macrophylla by integrating high-fidelity (HiFi) long-read sequencing generated by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) scaffolding. The assembled genome spans 1.13 Gb, with 93.29% of sequences anchored to 11 pseudochromosomes (scaffold N50 = 105.36 Mb), closely matching the estimated genome size based on k-mer analysis (1.07 Gb). Repetitive sequences account for 59.58% of the genome, with long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons representing 39.25% of these elements. A total of 28,548 protein-coding genes were predicted in the assembled genome, of which 27,936 (97.86%) were functionally annotated. This high-quality genome provides a valuable foundation for elucidating medicinal compound biosynthesis, stress resistance mechanisms, and the genetic improvement of F. macrophylla, while also enriching the genomic resources available for the Fabaceae family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

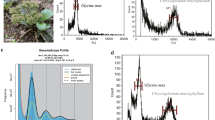

Flemingia macrophylla is a perennial shrub of the genus Flemingia in the family Fabaceae1,2. This evergreen species exhibits climbing or trailing growth habits2, trifoliate compound leaves bearing ovate to elliptical leaflets, and vibrant papilionaceous flowers with a tubular corolla base (Fig. 1a). It displays considerable ecological plasticity and is commonly found in open grasslands, shrublands, sunny forest margins, and along valley roadsides3,4. It is native to tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, including southern China (notably Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangxi provinces), Southeast Asia, and India5, and has also spread to Africa and South America6.

Photos and genomic characteristics of F. macrophylla. (a) The leaves, roots, and flowers of F. macrophylla. (b) Genomic characteristics of F. macrophylla. The tracks from outer to inner circle represent the eleven chromosomes (Chr1-Chr11), gene density, GC content, LAI score distribution, LTR content and syntenic gene blocks within the genome indicated by connecting lines. (c) K-mer depth distribution for genome size estimation of F. macrophylla. (d) The Hi-C interaction heatmap for F. macrophylla.

Flemingia macrophylla has a long history of traditional use and a growing body of scientific evidence supporting its diverse pharmacological activities. In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), it has been employed to dispel wind and eliminate dampness, promote blood circulation, and detoxify7. Its roots and stems are traditionally used to treat rheumatism and alleviate bone pain2,8. In Indian folk medicine, the leaves are commonly used in diabetes management7,9. Modern pharmacological studies further support its therapeutic potential by identifying bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, that exhibit significant in vitro antioxidant10, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activities2. In addition, the plant’s extracts are rich in legume-specific isoflavones11, which show neuroprotective potential against Alzheimer’s disease8,12 and therapeutic potential for osteoporosis13,14.

Although previous studies have assembled the chloroplast genome15 and nuclear genome16 of F. macrophylla, provided genetic insights for this medicinal plant, research at the nuclear genome level remains insufficient. In this study, we completed a chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of F. macrophylla using high-fidelity (HiFi) long-read sequencing generated by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), combined with chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) data, providing a high-quality genomic resource that complements the previously published Nanopore-based assembly by Ding et al.16. In terms of genome contiguity, the genome assembled in this study has a total size of 1.13 Gb, with a contig N50 of 68.75 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 105.36 Mb, both higher than those in the previously published version (59.43 Mb and 100.63 Mb, respectively16) (Table 1). Compared to previous studies that relied on Nanopore sequencing and multiple rounds of error correction, our approach leveraged highly accurate PacBio HiFi reads and the hifiasm assembler optimized for diploid genomes, resulting in a more contiguous and accurate assembly with fewer redundant sequences and minimal polishing steps17. Finally, 1.06 Gb (93.29%) of the assembled sequences were successfully anchored and oriented onto 11 pseudochromosomes. (Fig. 1b), thereby reducing the assembly fragmentation. By integrating transcriptome-based, homology-based, and de novo prediction approaches, this study predicted 28,548 protein-coding genes, with a BUSCO completeness of 97.8% (Table 2), representing an improvement over the previously published 97.6%16. A total of 27,936 genes (97.86%) were annotated across multiple databases (Table 3), outperforming the previously reported annotation rate of 95.01%16. The successful construction of a high-quality reference genome for F. macrophylla enriches the genomic resources of the Fabaceae, providing a solid foundation for future genomic and evolutionary studies of the genus Flemingia. This achievement ultimately contributes to the sustainable development and utilization of medicinal plant resources.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

In November 2023, young healthy roots of F. macrophylla were collected from one individual at the Guangxi Botanical Garden of Medicinal Plants, Nanning, Guangxi, China (22°51′30″ N, 108°22′39″ E). Leaves were cleaned, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, preserved on dry ice, and subsequently used for genomic DNA. The cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method was used for genomic DNA extraction18. For PacBio HiFi sequencing, two 20-kb SMRTbell libraries were prepared and sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II platform in Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) mode using two SMRT cells, generating 45.88 Gb of high-quality filtered data (Table 4). Roots were used for Hi-C library preparation (chromatin cross-linking, MboI digestion, end repair, proximity ligation, purification) and sequenced in paired-end mode (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. RNA was extracted from the roots using TRIeasy™ Total RNA Extraction Reagent (Yeasen, China). RNA-seq libraries were constructed and then sequenced in paired-end mode (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating high-quality transcriptomic data for gene prediction and functional annotation.

Genome survey

To estimate the genome size, heterozygosity and repeat content, a 21-mer frequency analysis was performed using Jellyfish v2.3.019 on high-quality filtered HiFi reads. The k-mer frequency distribution was then modeled with GenomeScope v.2.020 under a diploid assumption (-p 2). The analysis estimated a genome size of approximately 1.07 Gb, with a low heterozygosity rate of 0.001% and a repeat content of 59.7%. The unique sequence portion accounted for 41.5% of the genome, and the major k-mer peak occurred at a coverage depth of ~18.8 × . The estimated sequencing error rate was 0.156%, and the model exhibited a high goodness-of-fit (100%), indicating that the data were well suited for genome characterization (Fig. 1c).

De novo genome assembly

HiFi long reads generated by PacBio sequencing technology were de novo assembled using hifiasm v0.25.021 with default parameters optimized for diploid genomes. The ~45.88 Gb of filtered HiFi data correspond to an estimated ~43 × coverage of the ~1.07 Gb genome, providing a solid basis for the assembly. The primary assembly output was then processed with Purge Haplotigs v1.0.422 to remove residual redundancies, yielding a polished, non-redundant haploid assembly. The F. macrophylla genome assembly totaled 1.13 Gb, with a contig N50 of 68.75 Mb. (Table 3). To improve genome assembly contiguity23, draft contigs were scaffolded into a chromosome-scale assembly using the 3D-DNA pipeline24, guided by chromatin interaction data derived from uniquely mapped Hi-C reads25. The workflow was as follows:

Hi-C data preprocessing and integration: Hi-C sequencing data were processed using Juicer26 to generate a genome-wide contact frequency matrix. Leveraging the principle that physically proximal genomic regions exhibit higher interaction frequencies, contigs were preliminarily assigned to putative chromosome groups based on their interaction patterns. Chromosomal scaffolding: the 3D-DNA software was employed to construct chromosome-scale scaffolds by ordering, orienting, and estimating inter-contig gaps between contigs. Manual curation: using Juicebox27, Hi-C contact heatmaps were examined to manually adjust scaffold orientations, correct misassemblies, and validate the contig order, ensuring alignment with the physical interaction patterns captured by Hi-C.

Ultimately, a chromosome-level genome assembly was successfully constructed (Fig. 1d). Assembly statistics were computed using QUAST v5.3.028. A total of 1.06 Gb of sequences were anchored to eleven putative chromosomes (Table 5), with an anchoring rate of 93.29%. The scaffold N50 of the final chromosome-level genome reached 105.36 Mb, representing a 53% improvement over the contig N50 (68.75 Mb) from the preliminary assembly. This result clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of Hi-C technology in facilitating chromosome-scale genome assembly by capturing long-range genomic interactions.

Repetitive sequence annotation

The presence of repetitive sequence regions in genomes can compromise the accuracy of gene prediction and increase computational burden. A combination of de novo and homology-based sequence prediction approaches was employed to identify and mask repetitive sequences in the F. macrophylla genome prior to structural annotation. De novo prediction was performed using RepeatModeler v2.0.529, which integrates RepeatScout v1.0.730 and RECON31 tools to identify, refine, and classify potential repetitive elements32, thereby constructing a custom repeat library. RepeatMasker v4.1.033 was subsequently applied to annotate repetitive sequences using a combined repeat library consisting of the custom library and the Dfam 3.1 database34. In F. macrophylla, repetitive sequences accounted for approximately 59.58% of the genome, with LTR retrotransposon representing the most abundant class at 39.25% (Table 6).

Gene structure prediction

Structural prediction of the F. macrophylla genome was performed using GETA v2.4.12 (https://github.com/chenlianfu/geta), which integrates three approaches: transcriptome-based, homology-based, and de novo predictions. For transcriptome-based prediction, raw reads were quality trimmed using Trimmomatic35, aligned to the genome using HISAT236, and coding sequences were predicted with TransDecoder v5.7.1 (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). Homology-based prediction was performed using GenWise v2.4.137, with protein sequences from five closely related species (Lupinus albus, Cicer arietinum, Glycine max, Phaseolus acutifolius, and Lotus japonicus) as queries. De novo gene prediction was carried out using AUGUSTUS v3.5.038. By integrating these three approaches, GETA produced accurate gene predictions (Table 3). BUSCO assessment showed 97.8% complete BUSCOs, further indicating a high-quality annotation (Table 2).

Gene functional annotation

Protein sequences of F. macrophylla were aligned against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant (NR) and Swiss-Prot protein databases using DIAMOND BLASTP v2.1.10.16439, with an E-value cutoff of 1e-5, to retrieve sequence similarity and functional annotation information. Functional annotations were further assigned using eggNOG-mapper v2.1.1240 based on the eggNOG database, which also provided Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway information. InterPro annotations were obtained using InterProScan v5.54-87.041. Gene Ontology (GO) terms were integrated from the annotation results of both eggNOG-mapper and InterProScan (Table 3).

Non-coding RNA annotation

The transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1242 with default parameters. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and other non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) were annotated using Infernal v1.1.543 in combination with the Rfam 15.044 database. In total, 1,116 rRNA genes, 2,265 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) genes, 124 microRNA (miRNA) genes, 583 tRNA genes, and 8 small RNA (sRNA) genes were identified in the F. macrophylla genome (Table 3).

Data Records

The sequencing reads generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1308524 (Hi-C reads: SRR3519686345, PacBio HiFi reads: SRR3519686446, and RNA-Seq reads: SRR3519685847, SRR3519685948, SRR3519686049, SRR3519686150, SRR3519686251). The chromosome-level genome assembly and associated annotation files have been deposited in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29986939.v4)52.

Technical Validation

QUAST v5.3.028 was employed to evaluate the genome assembly quality, focusing on assembly size and continuity. The assembled genome size reached 1.13 Gb, with a contig N50 of 68.75 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 105.36 Mb (Table 3). Genome assembly completeness was assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v5.8.353 with the embryophyta_odb10 dataset54. A total of 93.4% of BUSCOs were identified as complete and single-copy, 3.5% as duplicated, 1.2% as fragmented, and 1.9% as missing (Table 2). The high overall completeness (96.9%) and low fragmentation rate indicate that the genome assembly of F. macrophylla is highly contiguous and reliable55. The LTR Assembly Index (LAI) was further used to evaluate the assembly quality of LTR retrotransposon regions, with higher scores reflecting greater structural integrity56. Using LTR_retriever v3.0.157, the assembled genome achieved an LAI score of 14.31, exceeding the threshold of 10 for a moderately high-quality LTR assembly and thus indicating high structural integrity in these regions56. Additionally, BUSCO assessment of the predicted gene set revealed 97.8% complete BUSCOs against the benchmark set of 2,326 conserved genes (Table 2).

Data availability

The sequencing reads generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1308524, which comprises the Hi-C data (SRR35196863), PacBio HiFi reads (SRR35196864), and RNA-Seq data (SRR35196858-SRR35196862). The corresponding chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation files are available on Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29986939.v4).

Code availability

All software tools were applied in strict accordance with the official guidelines of the respective bioinformatics programs. Version numbers and parameters are provided in the Methods section. No custom code was used.

References

Mui, N., Ledin, I., Udén, P. & Van Binh, D. Effect of replacing a rice bran–soya bean concentrate with Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) or Flemingia (Flemingia macrophylla) foliage on the performance of growing goats. Li. vest. Prod. Sci. 72, 253–262 (2001).

Tiemann, T. T. et al. Effect of the tropical tannin-rich shrub legumes Calliandra calothyrsus and Flemingia macrophylla on methane emission and nitrogen and energy balance in growing lambs. Animal 2, 790–799 (2008).

Andersson, M. S., Schultze-Kraft, R., Peters, M., Hincapié, B. & Lascano, C. E. Morphological, agronomic and forage quality diversity of the Flemingia macrophylla world collection. Field Crops Res. 96, 387–406 (2006).

Andersson, M. S. et al. Molecular characterization of a collection of the tropical multipurpose shrub legume Flemingia macrophylla. Agroforest. Syst. 68, 231–245 (2006).

Lai, W.-C. et al. Phyto-SERM constitutes from Flemingia macrophylla. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 15578–15594 (2013).

Phesatcha, B., Viennasay, B. & Wanapat, M. Potential use of Flemingia (Flemingia macrophylla) as a protein source fodder to improve nutrients digestibility, ruminal fermentation efficiency in beef cattle. Anim. Biosci. 34, 613–620 (2021).

Fatema, K. et al. Antioxidant and antidiabetic effects of Flemingia macrophylla leaf extract and fractions: in vitro, molecular docking, dynamic simulation, pharmacokinetics, and biological activity studies. BioResources 19, 4960–4983 (2024).

Shiao, Y.-J., Wang, C.-N., Wang, W.-Y. & Lin, Y.-L. Neuroprotective flavonoids from Flemingia macrophylla. Planta Med. 71, 835–840 (2005).

Syiem, D. & Khup, P. Z. Evaluation of Flemingia macrophylla L., a traditionally used plant of the north eastern region of India for hypoglycemic and anti-hyperglycemic effect on mice. Pharmacologyonline 2, 355–366 (2007).

Gahlot, K., Lal, V. K. & Jha, S. Total phenolic content, flavonoid content and in vitro antioxidant activities of Flemingia species (Flemingia chappar, Flemingia macrophylla and Flemingia strobilifera). Pharmacologyonline 6, 516–523 (2013).

Blázovics, A., Csorba, B. & Ferencz, A. The beneficial and adverse effects of phytoestrogens. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 7, 1–35 (2022).

Niu, S.-L. et al. Prenylated isoflavones from the roots of Flemingia philippinensis as potential inhibitors of β-amyloid aggregation. Fitoterapia 155, 105060 (2021).

Guo, L. et al. Effect of Flemingia macrophylla mixed powder on improving bone function in rats. J. Environ. Occup. Med. 38, 294–302 (2021).

Ho, H.-Y., Wu, J.-B. & Lin, W.-C. Flemingia macrophylla extract ameliorates experimental osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 752302 (2011).

Qin, X. et al. The complete chloroplast genome of Flemingia macrophylla (Willd.) Prain (Fabaceae) from Guangxi, China. Mitochondrial DNA B 6, 3378–3380 (2021).

Ding, Y. et al. High-quality assembly of the chromosomal genome for Flemingia macrophylla reveals genomic structural characteristics. BMC Genomics 26, 535 (2025).

Yu, W. et al. Comprehensive assessment of 11 de novo HiFi assemblers on complex eukaryotic genomes and metagenomes. Genome Res. 34, 326–340 (2024).

Porebski, S., Bailey, L. G. & Baum, B. R. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 15, 8–15 (1997).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 11, 1432 (2020).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Roach, M. J., Schmidt, S. A. & Borneman, A. R. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 460 (2018).

Shi, M. et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of the mangrove climber species Dalbergia candenatensis. Sci. Data 11, 1187 (2024).

Zhong, Y. et al. Chromosomal-level genome assembly of the orchid tree Bauhinia variegata (Leguminosae; Cercidoideae) supports the allotetraploid origin hypothesis of Bauhinia. DNA Res. 29, dsac012 (2022).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075 (2013).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358 (2005).

Bao, Z. & Eddy, S. R. Automated de novo identification of repeat sequence families in sequenced genomes. Genome Res. 12, 1269–1276 (2002).

Wang, R. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Malus niedzwetzkyana, the mother of Rosybloom crabapple. Sci. Data 12, 211 (2025).

Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 5, 4.10.1–4.10.14 (2004).

Wheeler, T. J. et al. Dfam: a database of repetitive DNA based on profile hidden Markov models. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D70–D82 (2013).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Kim, D. et al. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol 37, 907–915 (2019).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995 (2004).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2115–2122 (2017).

Blum, M. et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D344–D354 (2021).

Chan, P. P. et al. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096 (2021).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Ontiveros-Palacios, N. et al. Rfam 15: RNA families database in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D258–D267 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196863 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196864 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196858 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196859 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196860 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196861 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35196862 (2025).

Yuan, T. & Chen, L.-Y. The Chromosome-scale genome assembly of Flemingia macrophylla. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29986939.v4 (2025).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. In Gene Prediction: Methods and Protocols (ed. Kollmar, M.) 227–245 (Springer, Cham, 2019).

Simão, F. A. et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. High-quality chromosome-level de novo assembly of the Trifolium repens. BMC Genomics 24, 326 (2023).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126 (2018).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32370242). Construction of Southern Medicine Germplasm Resource Base for Guangdong Northern (2024B1212060006), and China Agriculture Research System (CARS-21).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lingyun Chen and Kunhua Wei conceived and designed the research. Ying Liang, Ying Hu, Yunfang Zhang and Baoyou Huang collected and prepared the samples. Ting Yuan analyzed the data results and wrote the manuscript. Ting Yuan and Xiangyu Wang modified the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, T., Wang, X., Liang, Y. et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of Flemingia macrophylla. Sci Data 13, 108 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06424-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06424-4