Abstract

Along with the increasing demand for the TiO2 pigment, the ilmenite smelting process has also become significant because it can utilize both rock- and sand-type ilmenite. However, due to the high liquidus temperature of the TiO2 slag system, the smelting process is highly energy consuming. In the present study, the viscosity of molten ilmenite slag was estimated using molecular dynamic simulations at a high temperature to achieve an appropriate and efficient slag design. To verify the validity of the simulation technique, experimental measurements were performed in parallel and their results were compared. The effects of FeO and Na2O addition on viscosity of TiO2 slag were also investigated. The addition of Na2O as a flux enhanced the ilmenite smelting process by not only lowering the liquidus temperature but also slowing the drastic viscosity increase. Statistical information obtained from the molecular dynamic simulations revealed a three-dimensional TiO6 octahedral network structure. The relationship between viscosity and structural change with varying FeO and Na2O concentrations was explored considering the coordination number of Ti and various bonding types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Both titanium and titanium dioxide (TiO2) are widely used worldwide in the production of white pigments, biomaterials, aircraft materials, and construction materials owing to their advantageous properties such as high refractive index, non-toxic characteristics, bio-affinity, high specific strength, and high corrosion resistance. Over 7 million tons of titanium mineral concentrate is produced globally per annum in the mineral form of rutile TiO2 and sand- or rock-type ilmenite (FeTiO3)1. Of these 7 million tons, approximately 94% is utilized for pigments, and the rest is used for titanium metal (3%) and welding rod applications (2%)2. According to the U.S. Geological Survey3, global consumption of TiO2 for the production of white pigments is estimated to increase by 4% annually for the next 10 years. The global titanium metal market is also expected to increase by approximately 7% annually owing to steady growth in its industrial demand for power generation in China and the aerospace industry in the US and EU4.

Naturally occurring rutile mineral, which has high TiO2 purity of above 95%, is ideal feedstock for TiO2 pigment and titanium metal production. However, its limited supply and high price mean that ilmenite ore is extensively used as an alternative5. Because ilmenite ore comprises only 30–65% TiO2, concentration and beneficiation processes are necessary prior to its use in the production of TiO2 pigments and titanium metal. Several processes have been proposed for improving ilmenite ores by separating Fe from TiO2. Three methods are generally adopted depending on the type of ilmenite feedstock: the Becher process, the Benelite process, and the ilmenite smelting process. Compared to Becher and Benelite processes, the ilmenite smelting process has an advantage in that most types of ilmenite ore can be applied as feedstock, and Fe is largely collected as a form of pig iron. As a result, the ilmenite smelting process is employed worldwide; its total annual production capacity of TiO2 slag is approximately three times that of synthetic rutile produced by the Becher and Benelite processes6.

Although the ilmenite smelting process is environmentally friendly and offers process flexibility, it has two major drawbacks: it requires high energy consumption and “upgraded slag process” for achieving high-grade TiO2 feed is optionally needed. The ilmenite smelting process is based on carbothermic reduction. During the process, FeO in ilmenite ore is reduced by anthracite and forms molten iron and TiO2-concentrated slag. Due to the high liquidus temperature of TiO2-concentrated slag, the operating temperature is approximately 1923–1973 K. However, when the amount of FeO in the slag reduces below 9 wt%, there is a drastic increase in the slag liquidus temperature, which causes a sharp increase in electricity consumption. For this reason, 9 wt% FeO is considered the economically critical composition for TiO2 slag7. As a result, the maximum concentration of TiO2 in ilmenite smelting slag is approximately 80–85 wt%.

To achieve a higher concentration of TiO2 in the final slag, the addition of a flux has been considered to decrease the liquidus temperature and further reduce the FeO content in the ilmenite slag. Highly reduced slag systems with below 5 wt% FeO have been demonstrated via the addition of a sodium oxide flux at a relatively low bath temperature of approximately 1873 K8,9. It should be noted that these studies were performed on pilot scales using carbon crucibles, and the method was not adopted in practice owing to high refractory erosion from alkali attack. However, in 1995, the introduction of a freeze-lining technique to the ferro-alloy smelting process led to innovations in refractory erosion protection10. Owing to this technology, various oxides such as K2O and B2O3 have recently been considered as practical flux options for the ilmenite smelting process11,12. The addition of a flux into the ilmenite smelting process could innovatively improve the process conditions and energy efficiency by drastically lowering the operating temperature.

The addition of flux into ilmenite slag affects not only the liquidus temperature but also the thermophysical properties of the slag. Viscosity is one of the most crucial properties because it is closely related to the slag foaming characteristic, the kinetics of the reduction reaction, and the effective separation of the slag and metal13,14. However, in spite of its practical importance, only a few experimental studies have investigated the viscosity of ilmenite smelting slag systems, and only with limited slag composition ranges15,16,17,18. Due to the extremely high melting temperature of high-TiO2 slag systems, experimental measurements are challenging. Thus, to properly design an ilmenite slag system considering the effects of flux additions, a prediction method for the viscosity of the TiO2–FeO-based system should be established.

In the present study, the viscosities of the FeO–TiO2 binary system and the FeO–TiO2–Na2O ternary system were measured experimentally, and the structures and viscosities were estimated using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Thus, the calculated viscosities were compared with the experimental results. After confirming the validity of the potential function used in the MD simulations, the effect of a high concentration of Na2O on the viscosity of the TiO2–FeO system was estimated. The simulations suggest that a large addition of Na2O can achieve an energy-efficient ilmenite smelting process at relatively low temperature. Finally, the effect of the TiO6 octahedral network structure on viscosity was investigated by using statistical structure information obtained from the MD simulations.

Results and Discussion

Effect of temperature and composition on viscosity

Figure 1 shows the temperature dependence of viscosity on the varying FeO/TiO2 ratio. (The measured viscosity values of present study are listed in Supplementary Table S1) Compared to other iron and steel making slag systems with viscosities of approximately 2 dPa∙s at 1823 K, the present FeO–TiO2-based slag systems had extremely low viscosities. In addition, compared to the conventional silicate-based steelmaking slag system, the effect of temperature on viscosity was relatively small in the FeO–TiO2 system above its liquidus temperature. Because the Arrhenius-type plot of inverse absolute temperature and logarithm of viscosity indicates the activation energy, the present finding implies a minute structural change in the TiO2-based network system as temperature varies. However, drastic viscosity increases were observed below the liquidus temperature. Since slag foaming is directly related to the slag viscosity19, the abrupt increase in viscosity; that is the lack of slag fluidity, caused sudden and massive slag foaming during the ilmenite smelting process. Because such uncontrollable massive froth formation forces a furnace shutdown15, the operation should be carried out and precisely controlled at a temperature sufficiently higher than the liquidus temperature. The effect of Na2O addition on the temperature dependence of viscosity in the 2FeO–3TiO2 system is shown in Fig. 2. A greater addition of Na2O resulted in a lower liquidus temperature. Even a small addition of Na2O (3 mol%) drastically decreased the liquidus temperature by approximately 150 K. With more than 6 mol% Na2O, a relatively moderate increase in viscosity near the liquidus temperature was observed, which would prevent massive surges of slag foaming during actual operation. According to thermodynamic calculations by using FactSage 7.0 (Thermfact and GTT-Technologies, Motreal, Canada), drastic decreasing of liquidus temperature can be observed as Na2O addition in the FeO-TiO2 system. In addition, the relative fraction of pseudobrookite phase; that is the primary solidification phase, decreases as increasing of Na2O at below its liquidus temperature. According to Wang et al.20 who found the relationship between thermodynamics and kinetics of Bain transition in pure iron, the decrease of driving force (│ΔG│) for phase transformation is correlated with the increase of energy barrier (Q). It could be inferred that the decreasing of driving force (│ΔG│); that is thermodynamic parameter, results in the slowing kinetics by increasing energy barrier (Q). In the present study, the thermodynamic calculations revealed that the addition of Na2O restrains the formation of pseudobrookite phase by decreasing of its Gibbs free energy change (│ΔG│). As a result, it would be inferred that the energy barrier (Q) of phase transformation increases with higher concentration of Na2O in the FeO-TiO2 slag system. Therefore, the lowering liquidus temperature by decreasing of Gibbs free energy change (│ΔG│) of the formation of psedobrookite phase results in the slowing the drastic increasing of viscosity by increasing of energy barrier (Q) of phase transformation as higher concentration of Na2O.

Therefore, it can be expected that the addition of Na2O as a flux into the ilmenite smelting process could enhance the operation conditions and energy efficiency. Considering the lowering liquidus temperature and reducing of the drastic increasing of viscosity, approximately 6 mol% of Na2O addition would be suitable for the better operation in the ilmenite smelting process. Since the addition of Na2O decreases the liquidus temperature of slag system, a further reduction of FeO can be expected under the same operation conditions. According to previous studies8,9, highly reduced TiO2 slag with below 5 wt% FeO can be obtained by adding Na2O as flux in the ilmenite smelting process. Since the ilmenite smelting slag contains approximately 10 wt% FeO, a further 5 wt% reduction of FeO would result in an approximately 5% increase in pig iron production.

Figure 3 shows the effect of FeO concentration on the viscosity of the FeO–TiO2 system. A higher concentration of FeO resulted in a decreased viscosity. A similar dependency of viscosity on FeO concentration was demonstrated in a previous work21. In that study, the ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+) ratio was approximately 10, which is similar to in the present system. Nevertheless, in spite of the similar oxygen potential conditions, the previous work21 was carried out at 1773 and 1673 K, which is lower than the liquidus temperature of FeO–TiO222. It seems that the decreased liquidus temperature may have resulted from the presence of uncontrolled impurities during their measurements. As shown in Fig. 4, the Na2O addition also decreased the viscosity of the 2FeO–3TiO2 system. However, compared to the drastic effect on liquidus temperature, the effect on viscosity is relatively minor.

Even in an equilibrium state, atoms and molecules are constantly moving. This collective motion of particles is called Brownian motion, which can be described by the self-diffusion coefficient (D). Each atom has its own D value. During the MD simulation, D can be obtained from the mean square displacement (MSD), that is, the average displacement of a target atom during a certain time t, as given by Eq. (1) 23.

where ri(t) is the position of atom i at time t, and N is the number of atoms. The angular brackets indicate the average over atomic positions23.

Following Einstein’s relations for diffusivity, the value of D for each species can be calculated based on the obtained MSD as expressed in Eq. (2) 23,24,25,26,27.

Finally, viscosity (η) can be calculated from the relationship between η and D by the Stokes–Einstein equation given in Eq. (3) 25,27:

where k is Boltzmann’s constant, T is absolute temperature (K), and λ is the jumping distance (Å) during diffusion. In the present calculation, the jumping distance was set as the diameter of oxygen (2.8 Å)27.

Figure 5 shows the obtained MSDs for the present FeO–TiO2 and 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O systems at 1823 K. Depending on atomic species, different MSD slopes were obtained as a function of time (fs). Across the studied FeO–TiO2-based systems, Ti atom diffusion was commonly the slowest because TiO2 forms a TiO6 network structure. Thus, the diffusion of Ti atoms plays a determining role in the rheological behaviour of the present system. For this reason, viscosity was calculated based on the MSD of Ti atoms. Further discussion regarding the TiO2 structure is given in the following section.

As shown in Figs 3 and 4, the calculated viscosities were in excellent accordance with the measured viscosities, indicating the validity of the employed MD calculations for the FeO–TiO2 and 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O systems. In addition, the viscosity of the FeO–TiO2 system at 1973 K with varying compositions was evaluated based on the present MD simulation, as shown in Fig. 3. Although the results of the MD calculation for viscosity should be verified at high temperature (1973 K) to ensure accurate viscosity modelling, the present results suggest the possibility of an efficient viscosity estimation, even at high temperatures where experimental measurements are challenging. This simple and reliable estimation of viscosity would be expected to aid in the design of slag systems for the ilmenite smelting process. It should be noted that Ti3+ also exists in ilmenite smelting slag (Ti3+/Ti4+ = 0.29) due to its extreme reducing conditions28. Such extremely reducing conditions cannot be achieved in our study; thus, Ti4+ is in a thermodynamically stable state herein. For this reason, only Ti4+ was considered in our MD simulation. However, for the accurate prediction of viscosity in the real ilmenite smelting process, Ti3+ should be considered in the MD simulation.

Effect of titanate structure on viscosity

Figure 6 shows the radial distribution functions (RDFs, gij(r)) of the 2FeO–3TiO2 system and 2FeO–3TiO2 with 9 mol% Na2O system at 1823 K obtained from the MD simulations. The RDF describes the average number density of particles j from a reference particle i as a function of distance r. Relatively sharp peaks were observed at distances less than 2.8 Å between Ti–O, Fe–O, O–O, and Na–O, whereas broadened peaks with gentle slopes were present in other combinations at distances greater than approximately 3.0 Å. Therefore, it can be inferred that meaningful bonding only formed between cations and oxygen or between oxygen and oxygen, which is similar to other silicate-based slag systems.

RDFs from MD simulations of the (a) 2FeO–3TiO2 system with no Na2O (Fe–Fe, green; Ti–Ti, grey; Ti–Fe, red; O–O, orange; Fe–O, purple; Ti–O, blue) and (b) the 2FeO–3TiO2 system with 9 mol% Na2O (Na–Na, pink; Fe–Fe, purple; Ti–Na, green; Fe–Na, light blue; Ti–Ti, grey, Ti–Fe, dark red; Na–O, yellow-green; O–O, blue; Fe–O, red; Ti–O, black) at 1823 K.

Via integration of the RDF from 0 to a cut-off radius, the coordination numbers (CNs, N(r)) of each atomic species bonded to oxygen were calculated using the MD simulation results. As shown in Fig. 7, the coordination numbers of Ti, Fe, O, and Na atoms were considered because they have meaningful bonds with O atoms in the present system. A flat plateau was found only for Ti–O, indicating that the coordination number of Ti was approximately 6. Thus, each Ti atom forms an octahedral structure bonded to six-oxygen atoms. On the other hand, the coordination number curves of other atoms did not show characteristic plateau regions, but instead simply increased at distances greater than 2 Å. Although Fe–O and Na–O formed meaningful bonds, they did not exhibit a regular structural unit. Hence, in the FeO–TiO2 and 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O systems, the TiO6 octahedral structure is the main structural unit, and Fe or Na would compensate for the ionic charge of the TiO6 octahedral unit.

Although the formation of a TiO6 octahedral structure in the FeO–TiO2 slag system has previously been reported13,29,30, the formation of a three-dimensional network structure by TiO6 octahedra has not yet been clearly verified. Considering that TiO2 forms a three-dimensional network structure via linking of TiO6 octahedral units in rutile TiO2 and ferrous-pseudobrookite (FeTi2O5) crystals29, the formation of a three-dimensional network structure in the molten state should be considered. To evaluate the existence of a three-dimensional network structure consisting of TiO6 octahedral units, bond angle distributions (BADs) of O–Ti–O and Ti–O–Ti were investigated. In the present study, BADs were calculated using the interactive structure analysis of amorphous and crystalline systems (ISAACS) program31.

The O–Ti–O BAD is shown in Fig. 8, displaying distinct peaks at approximately 90° and 170° that indicate the presence of a TiO6 octahedral structure in the present system. The much higher peak observed at 90° than at 170° suggests a slightly distorted octahedral structure24. The compositional change does not result in a significant bond angle change, implying a stable structure of the TiO6 octahedral unit. The O–Ti–O BAD is based on the bond angle between two O atoms on a centre Ti atom in the TiO6 octahedral unit. On the other hand, the Ti–O–Ti BAD indicates the bonding between two Ti atoms linked through one or two O atoms. Therefore, the existence of a regular Ti–O–Ti BAD confirms a three-dimensionally linked network structure of TiO6 octahedral units in the present system. As shown in Fig. 9, two distinctive broad peaks are centred at 95° and 130° in the Ti–O–Ti BAD, representing the edge-sharing and corner-sharing bond angles, respectively27,32. Following the Gaussian deconvolution of the obtained Ti–O–Ti BAD peaks, the relative fractions of edge-sharing and corner-sharing structural units were determined based on the peak area ratios. As shown in Fig. 10, the relative fraction of edge-sharing units gradually decreases as TiO2 concentration increases. Because two octahedral units are linked via one sharing O atom, corner sharing has a lower bond strength than edge sharing27. However, in spite of the decreasing relative proportion of edge sharing, increasing viscosity was observed at higher TiO2 concentrations in the present FeO–TiO2 system. In addition, although viscosity decreased at higher Na2O concentrations, the relative proportion of edge and corner sharing did not significantly change. Therefore, these results indicate that the type of connection between two octahedral units of TiO6 is not directly related to its rheological behaviour.

Figure 11 shows the change in coordination number of the Ti atom with varying FeO and Na2O concentrations. Further addition of FeO or Na2O to the FeO–TiO2 system leads to a decrease in coordination number from 5.5 to 5.1 or 5.5 to 5.35, respectively. Considering that the coordination number of Ti–O represents that average bonding of Ti atoms to O atoms, a decrease in coordination number implies the breaking of bonds between them. Since the TiO6 octahedral structure forms a network structure in the FeO–TiO2 slag system, the decrease of coordination number therefore indicates the depolymerization of TiO6 network structure via the formation of non-bridging oxygen (NBO). Thus, due to the network-modifying characteristics of FeO and Na2O33, their addition depolymerizes the TiO6 network structure. After modifying the TiO6 octahedral network structure, Fe2+ and Na+ ions act as ion compensators for NBO34. This is supported by a relatively sharp peak observed in the RDF (Fig. 6), implying a regular coupling between Fe2+/Na+ and O atoms.

In Fig. 12, the relative proportion of the three bond types (Ti–O–Ti, Fe–O–Ti, and Fe–O–Fe in the FeO–TiO2 system, and Ti–O–Ti, Na–O–Ti, and Na–O–Na in the 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O system), are described based on the MD simulation results at 1823 K. As shown in Fig. 12(a), a gradual decrease in the occurrence of Ti–O–Ti bonding is observed at higher concentrations of FeO, which indicates depolymerization of the TiO6 octahedral structure. In the FeO–TiO2 binary system, the occurrence of Fe–O–Ti bonding initially increases but decreases upon reaching 80 mol% FeO. In contrast, the occurrence of Fe–O–Fe bonding drastically increases above 90 mol% FeO. As the TiO6 octahedral structure is depolymerized by the FeO addition, the bonding between Fe, O, and Ti increases as a result of the charge compensation of NBO by Fe2+. However, above 90 mol% of FeO, the main structure is not a TiO6 octahedral unit but rather an FeO-based structure, although as shown in the coordination number curve in Fig. 7, it seems that FeO does not form a regular structural unit in the FeO–TiO2 system. Along with depolymerization of TiO6 structural units by FeO, FeO also forms Fe–O–Fe bonds based on the charge potential.

As shown in Fig. 12(b), addition of Na2O similarly results in decreased Ti–O–Ti bonding, indicating the depolymerization of the TiO6 octahedral structure. The increased relative proportion of Na–O–Ti bonds with higher concentrations of Na2O arises from the charge compensation of NBO by Na+ in the TiO6 structure. A small increase in the occurrence of Na–O–Na bonding implies that not all Na2O is consumed to depolymerize the TiO6 units, but that some Na2O naturally forms an ionic bond based on its potential in the molten 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O system.

These structural investigations allow for an explanation of the observed viscosity change with varying FeO and Na2O concentrations. As the FeO and Na2O concentrations increase, the coordination number of Ti atoms bonded to O atoms gradually decreases, indicating the depolymerization of the three-dimensional TiO6 network structure. As a result, the rheological behaviour of the molten oxide system improves and viscosity decreases. The decrease in the relative proportion of Ti–O–Ti bonds and increase in proportions of Fe–O–Ti and Fe–O–Fe or Na–O–Ti and Na–O–Na bonds confirmed the breaking of the titanate network and charge compensation of NBO.

Conclusions

To achieve an energy-saving and efficient ilmenite smelting process, this study considered a slag design with a lowered liquidus temperature via flux addition. MD simulations adopting Buckingham potentials were carried out to estimate ilmenite smelting slag viscosities at high temperatures. To verify the validity of the present simulation, calculations were performed on the relevant crystals (rutile, ilmenite, and Freudenbergite) at room temperature in advance. In addition, the viscosity of the FeO–TiO2-based slag system was experimentally measured at 1823 K for comparison with the calculated viscosities. Following the verification of the simulation potential, viscosities were estimated with varying concentrations of TiO2 at 1823 and 1973 K. In addition, the effect of Na2O as a flux on the ilmenite smelting process was studied. The viscosity measurement results indicated that the addition of Na2O enhances the operation conditions by not only lowering the liquidus temperature but also by slowing the drastic increase in viscosity. The addition of Na2O is thus expected to reduce the electrical consumption and prevent massive surges of slag foaming during the ilmenite smelting process. Furthermore, the calculated viscosities were in excellent accordance with the measured values, indicating the applicability of MD simulations for slag design in the ilmenite smelting process. By analysing the statistical information obtained from the MD simulation results, the existence of a three-dimensional network structure consisting of TiO6 octahedral units was verified. Increased FeO and Na2O concentrations were confirmed to depolymerize the titanate network structure by forming NBO, resulting in a decreased Ti coordination number and relative proportion of Ti–O–Ti bonds. In addition, Fe2+ and Na+ act as charge compensators, forming Fe–O–Ti and Na–O–Ti or Fe–O–Fe and Na–O–Na bonds.

Methods

Viscosity measurements

Reagent-grade ilmenite (FeTiO3), TiO2, FeO, and Na2CO3 were mixed to obtain target mole ratios. Measurements were carried out with up to 60 mol% TiO2 because the liquidus temperature exceeds 1873 K above 65 mol% TiO222, and such a high temperature cannot be stably maintained in our present measurement system. The mixtures were ground in an agate mortar for homogeneous mixing and put into a crucible (outer diameter φ = 41 mm, inner diameter φ = 40 mm, and height = 65 mm) and placed in a vertical furnace at 1573 K under an Ar atmosphere. After heating the sample to 1823 K and holding for 2 h, the viscosity measurement was carried out by introducing spindle at the centre of the molten oxide. In order to prevent chemical erosion of the crucible and spindle from the molten slag system, a Pt–10%Rh alloy was chosen as the material for the crucible and spindle.

The immersed spindle was rotated at 80 rpm, and the measured shear stress was recorded each second by a digital viscometer (DV2TLV; Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Middleboro, MA) calibrated with standard silicone oil at room temperature. After a 1 h measurement, the temperature was decreased by 25 K at 2.5 K/min. After 20 min of thermal equilibration time, the viscosity measurement was again carried out. This process of decreasing the temperature and measuring the viscosity was continued until the viscosity exceeded 10 Pa∙s. Once the viscosity exceeded 10 Pa∙s, the measurement was ceased, and the sample was reheated to 1823 K. After holding at 1823 K for 1 h, the fully melted sample was quenched on a water-cooled copper plate. The chemical composition of the obtained sample was analysed by using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, 5300DV, Perkin Elmer, NY, USA), and the results are listed in Table 1. The ferric (Fe3+) and ferrous (Fe2+) states of the system were analysed by using the K2Cr2O7 titration method (JIS M 8212:2005).

Molecular dynamics simulations

In the present study, the Buckingham potential was adopted to express the pair interatomic interaction between the cation and oxygen. The Buckingham potential, Eij(r), consists of two components as shown in Eq. (4), describing a short-range repulsive interaction and an attractive van der Waals force:

where r is the interaction distance, A, ρ, and C are potential parameters, and i and j indicate different atomic species35. The potential parameters for Ti, Fe, Na, and O atoms were obtained from Guillot and Sotor’s work36 because its applicability for the entire range of industrial oxide systems has been well proven23. The detailed atomic charges and Buckingham potential parameters are listed in Table 2. The cation–cation interactions were set to zero, because cation–oxygen and oxygen–oxygen interactions are the dominant factors in the oxide system at short ranges36,37.

Generally, MD simulation results of glass systems are compared with neutron structure factors obtained experimentally via neutron scattering to evaluate the validity of the applied potential and calculation procedure. However, due to the highly crystalline characteristics of the FeO–TiO2-based system, its glass neutron structure factor cannot be directly obtained. Thus, the experimental and calculated lattice parameters of related crystals were compared to evaluate the accuracy of the Buckingham potential for the FeO–TiO2 and FeO–TiO2–Na2O systems. Three crystal phases were considered: rutile (TiO2), ilmenite (FeTiO3), and Freudenbergite (Na(Ti3Fe)O8). As shown in Table 3, the deviations between measured38,39,40 and calculated lattice parameters were less than 3.6%, indicating the reliability of the presented potential and calculation conditions.

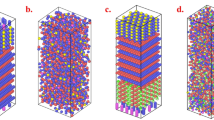

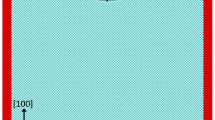

A classical MD simulation was carried out in three dimensions with approximately 8,000 atoms. To simplify the simulation, only the ferrous state of iron was considered. Because the ferrous to ferric ratio is more than 10, the effect of the ferric state on the present system would be insignificant. Randomly distributed atoms were generated by using the PACKMOL package41 in a fixed cubic box, and the LAMMPS MD code42 was applied for the MD simulations. To calculate the long-range coulombic interactions, the particle–particle particle–mesh (pppm) solver was applied with an absolute charge value of 10−5. The cut-off radius for the short-range and coulombic interactions was set to 11 Å. To remove the memory of the initial configuration, the system was maintained at 3000 K for 10 ps and 100 ps with NVT and NPT ensembles, respectively. Afterward, the system was cooled to 1973 or 1823 K at a rate of 1 K/ps with the NPT ensemble. Finally, to achieve an equilibrium state, the system was relaxed at 1973 or 1823 K for 200 ps and 200 ps with NPT and NVT ensembles, respectively.

References

Sahu, K. K., Alex, T. C., Mishra, D. & Agrawal, A. An overview on the production of pigment grade titania from titania-rich slag. Waste Manag. Res. 24, 74–79 (2006).

Blanchart, P. Extraction, Properties and Applications of Titania. In Industrial Chemistry of Oxides for Emerging Applications 255–309, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119424079 (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2018).

Bedinger, G. M. TITANIUM [ADVANCE RELEASE]. In 2015 Minerals Yearbook (U.S. Geological Survey, 2015).

van Tonder, W. SOUTH AFRICAN TITANIUM: Techno- Economic Evaluation of Alternatives to the Kroll Process. (Stellenbosch University, 2010).

Kang, J. & Okabe, T. Removal of Iron from Titanium Ore through Selective Chlorination Using Magnesium Chloride. Mater. Trans. 54, 1444–1453 (2013).

Cardarelli, F. Materials Handbook, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38925-7 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Sun, H., Wang, J., Dong, X. & Xue, Q. A literature review of titanium slag metallurgical processes. Metal. Int. 17, 49–56 (2012).

Elger, G. W., Wright, J. B., Tress, J. E., Bell, H. E. & Jordan, R. R. Producing Chlorination-Grade Feedstock From Domestic Ilmenite-Laboratory and Pilot Plant Studies (1986).

Nafziger, R. H. & Elger, G. W. Preparation of Titanium Feedstock From Minnesota Ilmenite by Smelting and Sulfation-Leaching (1987).

Duncanson, P. L. & Toth, J. D. The truths and myths of freeze lining technology for submerged arc furnaces. In INFACON X: Transformation through technology 488–499 (The South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2004).

Mehdilo, A. & Irannajad, M. Iron removing from titanium slag for synthetic rutile production. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 48, 425–439 (2012).

Fan, H. et al. Production of Synthetic Rutile from Molten Titanium Slag with the Addition of B2O3. JOM 69, 1914–1919 (2017).

Pistorius, P. C. & Coetzee, C. Physicochemical aspects of titanium slag production and solidification. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 34, 581–588 (2003).

Liu, S., Wang, L. & Chou, K. Viscosity measurement of FeO–SiO2 –V2O3 –TiO2 slags in the temperature range of 1644–1791 K and modelling by using ion-oxygen parameter. Ironmak. Steelmak. 49, 1–7 (2017).

Handfield, G. & Charette, G. G. Viscosity and structure of industrial high TiO2 slags. Can. Metall. Q. 10, 235–243 (1971).

Hu, K. et al. Viscosity of TiO2-FeO-Ti2O3-SiO2-MgO-CaO-Al2O3 for High-Titania Slag Smelting Process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B Process Metall. Mater. Process. Sci. 49, 1963–1973 (2018).

Gao, G., Yang, Y. & Yang, D. Viscosity and melting point determination of titanium slag. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 1, 51–66 (1987).

Zhao, Z., Ma, E. & Lian, Y. Behavior of Al2O3 in titanium slag. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 23, 36–38 (2002).

De Almeida, R. A. M., Vieira, D., Bielefeldt, W. V. & Vilela, A. C. F. Slag foaming fundamentals -A critical assessment. Mater. Res. 20, 474–480 (2017).

Wang, K., Shang, S. L., Wang, Y., Liu, Z. K. & Liu, F. Martensitic transition in Fe via Bain path at finite temperatures: A comprehensive first-principles study. Acta Mater. 147, 261–276 (2018).

Mills, K. C. Viscosities of molten slags. In Slag atlas (ed. Verein Deutscher Eisenhüttenleute (VDEh)) 359 (Verlag Stahleisen GmbH, 1995).

Grau, A. E. Liquidus temperatures in the TiO2-rich side of the FeO-TiO2 system. Can. Metall. Q. 18, 313–321 (1979).

Karalis, K. T., Dellis, D., Antipas, G. S. E. & Xenidis, A. Bona-fide method for the determination of short range order and transport properties in a ferro-aluminosilicate slag. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–15 (2016).

Lu, X., Deng, L. & Du, J. Effect of ZrO2 on the structure and properties of soda-lime silicate glasses from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 491, 141–150 (2018).

Lee, S. J. & Kang, E. T. A Study on the Structures of (62-x)CaO38Al2O3·xBaO Glasses by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 44, 175–181 (2007).

Ren, M., Lu, X., Deng, L., Kuo, P.-H. & Du, J. B2O3/SiO2 substitution effect on structure and properties of Na2O–CaO–SrO–P2O5 –SiO2 bioactive glasses from molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 14090–14104 (2018).

Fan, H. et al. Structural and transport properties of FeO-TiO2 system through molecular dynamics simulations. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 493, 57–64 (2018).

Guéguin, M. & Cardarelli, F. Chemistry and Mineralogy of Titania-Rich Slags. Part 1—Hemo-Ilmenite, Sulphate, and Upgraded Titania Slags. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 28, 1–58 (2007).

Bessinger, D. Cooling characteristics of high titania slags. (University of Pretoria, 2007).

Sommerville, I. D. & Bell, H. B. The Behaviour of Titania in Metallurgical Slags. Can. Metall. Q. 21, 145–155 (1982).

Le Roux, S. & Petkov, V. ISAACS-interactive structure analysis of amorphous and crystalline systems. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 181–185 (2010).

Zhang, S., Zhang, X., Bai, C., Wen, L. & Lv, X. Effect of TiO2 Content on the Structure of CaO–SiO2–TiO2 System by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. ISIJ Int. 53, 1131–1137 (2013).

Mysen, B. O. & Richet, P. Silicate Glasses and Melts. (Elsevier, 2005).

Connelly, A. J., Hyatt, N. C., Travis, K. P., Hand, R. J. & Maddrell, E. R. Predicting the preference for charge compensation in silicate glasses. Phys. Chem. Glas. - Eur. J. Glas. Sci. Technol. Part B 52, 64–67 (2011).

Xiang, Y. & Du, J. Effect of strontium substitution on the structure of 45S5 bioglasses. Chem. Mater. 23, 2703–2717 (2011).

Guillot, B. & Sator, N. A computer simulation study of natural silicate melts. Part I: Low pressure properties. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 1249–1265 (2007).

Corradini, D., Ishii, Y., Ohtori, N. & Salanne, M. DFT-based polarizable force field for TiO2 and SiO2. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 23, 074005 (2015).

Howard, C. J., Sabine, T. M. & Dickson, F. Structural and thermal parameters for rutile and anatase. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 47, 462–468 (1991).

Wechsler, B. A. & Prewitt, C. T. Crystal structure of ilmenite (FeTiO3) at high temperature and at high pressure. Am. Mineral. 69, 176–185 (1984).

Ishiguro, T. et al. Freudenbergite. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 34, 255–256 (1978).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Plimpton, S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support that was provided by the Basic Research Project (GP2017-025) of the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Kim performed molecular dynamic simulations and wrote the main part of the article. H. Park edited the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Park, H. Estimation of TiO2-FeO-Na2O slag viscosity through molecular dynamics simulations for an energy efficient ilmenite smelting process. Sci Rep 9, 17338 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53961-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53961-1

This article is cited by

-

The Effect of Ti2O3 Content on the Local Structure and Transport Properties of TiO2–Ti2O3–FeO System: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2025)

-

Unveiling the Amphoteric Behavior of TiO2 in Fused CaF2-TiO2-MgO-SiO2 Submerged Arc Welding Fluxes

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2025)

-

Effects of CaO and MgO on the Local Structure and Transport Characteristics of Titanate System: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2025)

-

Local Structure and Transport Characteristics of TiO2-FeO-Al2O3 System with Various FeO Contents Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2024)

-

Elucidating the role of preferential oxidation during ablation: Insights on the design and optimization of multicomponent ultra-high temperature ceramics

Journal of Advanced Ceramics (2022)

3,

3,  6,

6,  9.

9.

Calculated at 1823 K;

Calculated at 1823 K;  Calculated at 1973 K;

Calculated at 1973 K;  Lopatin et al.

Lopatin et al. Lopatin et al.

Lopatin et al.

Calculated.

Calculated.

) TiO6 octahedral units with various FeO and Na2O concentrations in the (a) FeO–TiO2 and (b) 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O systems at 1823 K.

) TiO6 octahedral units with various FeO and Na2O concentrations in the (a) FeO–TiO2 and (b) 2FeO–3TiO2–Na2O systems at 1823 K.

Ti–O–Ti;

Ti–O–Ti;  (Fe/Na)–O–Ti;

(Fe/Na)–O–Ti;  (Fe/Na)–O–(Fe/Na).

(Fe/Na)–O–(Fe/Na).