Abstract

Repeated pregnancy leaves young mothers nutritionally deprived which may in turn lead to poor infant growth. We measure the occurrence and persistence of stunting among offspring of young mothers who experienced repeated pregnancies using data from the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey. We selected mothers aged 14–24 years (n = 1,033) with singleton birth. We determined the length-for-age z scores (LAZ) at 12 and 24 months of the index child using the World Health Organisation 2007 growth standard. We fitted LAZ, stunting occurrence (i.e. LAZ < − 2) and persistence from 12 to 24 months into regression models and tested for the mediating effect of low birthweight and feeding practices. In these models, repeated pregnancy was analysed in an ordinal approach using number of past pregnancies of young mothers at birth of the index child. Compared to infants born to young mothers aged 14–24 years who had no previous pregnancies, those born to young mothers with repeated pregnancies have at least 0.15 (95% CI − 0.23, − 0.08) LAZ lower and are at higher chance of stunting by at least 40% (95% CI 1.19, 1.67) at 12 and 24 months. Similar cohorts of infants showed an elevated risk of persistent stunting from 12 through 24 months with a relative risk ratio of 1.51 (95% CI 1.21, 1.88). Optimal feeding practices substantially mediated stunting outcomes by further reducing the effects of repeated pregnancy to stunting occurrence and persistence by 19.95% and 18.09% respectively. Mediation tests also showed low birthweight in the causal pathway between repeated pregnancy and stunting. Repeated pregnancy in young mothers is a predictor of stunting among children under 2 years. Secondary pregnancy prevention measures and addressing suboptimal feeding practices are beneficial to mitigate the negative impact of repeated adolescent pregnancy on children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, stunting affects more than 100 million children under five1, and is associated with poor cognition, reduced school performance, immunodeficiency, and child mortality2. In addition to adverse health outcomes, stunted children tend to have poorer economic productivity and lower wages in adulthood3. These negative impacts make stunting, especially in ‘the first 1,000 days’4, a profound indicator of poor health, social inequality, and disadvantage.

The pathogenesis of stunting originates in the first 1,000 days, extending from early foetal development to 24 months after birth. Inadequate maternal nutrition and poor antenatal care can directly and indirectly result in an unhealthy intrauterine environment and poor foetal growth5. Immediately following birth, suboptimal infant feeding practices slow offspring’s growth rate5. For example, sub-optimal (i.e. late, inadequate and inappropriate) complementary feeding negatively affects infant nutrition due to the rapid increase in nutritional needs after 6 months of age. Diarrheal infections and hygiene practices related to poor socio-economic status (SES) can also lead to stunting due to nutrient malabsorption and high intestinal permeability6.

Early pregnancies play an important role in stunting, due the competing demands for young mothers’ pubertal development and the growth of the foetus7, 8. This leads to greater nutrition partitioning, which compromises the development of both mothers and foetus7, 8. A repeated pregnancy in adolescence aggravates this mechanism through further depletion of nutritional stores. This may result in preterm births, maternal complications, and low birthweight, which are in turn strong risk factors for offspring stunting1, 9.

Although current research indicates the impact of repeated pregnancy among young mothers on child stunting, there is a lack of rigorous evidence in support of this relationship. An analysis of prospective cohorts in developing countries showed lower length-for-age z scores (LAZ) at 24 months among offspring of 14- to 19-year-old mothers compared to older age groups10. In another study, an unadjusted correlation was observed in this study between LAZ and a parity of 2 or more10. On the other hand, a cross-sectional study revealed null associations between infant stunting and parity despite diminishing LAZ in an increasing parity score based on crude data11. These inconsistent findings call for the need to explore the impact of parity on stunting trajectories between 12 and 24 months. Trajectories indicating either persistence or recovery, especially during the peak age for stunting, may provide important information about long-term offspring outcomes.

We sought to explore the growth trajectories of the subsequent offspring of young mothers in the Philippines. As a developing country, the Philippines is an ideal site to explore this research question for two main reasons. Firstly, the Philippines has a high rate of fertility in young women compared to other low- and middle-income countries12. Secondly, one third of pregnant Filipino adolescents are undernourished13, which predisposes a high number of their children to poor nutrition.

In this study, we aim to measure the magnitude of the association between repeated pregnancy in young mothers and offspring stunting at 12 and 24 months, and its persistence from 12 up to 24 months. Our study also explores the potential mediating effect of low birthweight, as proxy to evaluate foetal growth and nutrition, and feeding practices at significant timepoints to further investigate the modifiability of stunting risks introduced by having repeated pregnancies (see S1). We define the women of interest in this study—those aged 14–19 and 20–24 years old—as ‘young mothers’ as per the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) definition14.

Methods

Cohort selection

We used the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey (CLHNS) conducted in Cebu City, Philippines15. It is a three-generation community-based cohort, comprised of households from four urban and seven surrounding rural areas. Using the Philippine’s 1980 census as the sampling frame, a single-stage cluster sampling technique was employed to randomly select barangays (basic geographical, administrative units in the Philippines). This survey recruited 3,327 pregnant women, which is representative of women of reproductive age in Cebu City. From this, 3,080 women aged 14–47 years old with singleton livebirths were included in the final sample for follow-up. Details about CLHNS sampling technique were discussed in a separate paper15.

In this study, we used the 1983–1986 CLHNS data which consist of the baseline and bimonthly follow-up information of women surveyed. While this dataset describes young mothers 35 years ago, results from this study are still relevant in the Philippines and other developing countries due to consistent trends of adolescent fertility and repeated adolescent pregnancy as well as patterns of poor infant feeding habit among young mothers across years12, 16, 17. Baseline data, which include pregnancy history, household demographics, and socio-economic status were collected during the second to third trimester of pregnancy, followed by an immediate postpartum interview using a validated questionnaire15. Afterwards, bimonthly data collection for 24 months was conducted to follow the health and nutritional status of the mother and the index child.

In the case of this study, we only used the data collected at 12 and 24 months. Maternal height and infant length were measured using calibrated meter sticks and infantometers15, 18. Data collectors were trained and assessed for proficiency using the Habicht procedure19. We used data from 1,284 mothers aged 14–24 years and their index children who had complete data at the 12- and 24-month data collection points. The retention rate was 88% at the 24-month follow-up.

Outcome measure

We used the WHO’s 2007 growth standard to derive the length-for-age z-score (LAZ) of the index child20. LAZ was calculated by dividing the difference between the observed value and the mean value of the reference population by the standard deviation of the reference population. Calculation was automated in Stata using the zanthro macro21.

Using this score, we defined stunting as LAZ < − 2 at 12 and 24 months. We created a measure of persistence of stunting from 12 to 24 months based on classifications developed by previous studies22. Index children who were stunted at both 12 and 24 months were classified as “persistent”; those stunted at 12 months but not at 24 months were classified as “recovered”; those stunted only at 24 months were classified as “late incident”; and those who did not experience stunting were classified as “normal”.

Exposure

We used the number of past pregnancies in reference to the index child to measure repeated pregnancies. This means that children from a repeated pregnancy are born to young mothers who have at least one past pregnancy. In our analyses, we considered repeated pregnancy as a count variable to enable comparison in an ordinal approach.

We adjusted our analyses for child’s sex, maternal height, occurrence of pregnancy complications, frequency of antenatal visits (i.e. did or did not have ≥ 4 antenatal visits starting 1st trimester), and occurrence of infant diarrhea within seven days before the survey. We also measured and adjusted our analyses for socio-economic factors: maternal and paternal education and employment (i.e. employed or unemployed), and income class, at baseline and during 12-month follow-up. Instead of using all levels of education, we categorised maternal and partner’s education into completion and non-completion of secondary education. We used the monthly household income from all sources and created three income classes using Cebu’s average household income23, 24.

Statistical analyses

Univariate linear and logistic regression analyses were used to assess associations between repeated pregnancy and stunting outcomes: LAZ and stunting occurrence at 12 and 24 months, and stunting persistence. Multivariable models were used to adjust for confounders mentioned above. To measure the relationship between repeated pregnancy and stunting persistence, we used multinomial logistic regression since persistence has four possible discrete outcomes (i.e. persistent, recovered, late incident, and normal). Regression coefficients in this analysis were expressed as relative risk ratio. We compared the risk of stunting persistence among children of women who had more repeated pregnancies with children of women who had no or fewer repeated pregnancies.

Mediation tests were conducted via low birthweight and poor feeding practices since low birthweight (i.e. < 2,500 g) is on the causal pathway between parity and stunting, and feeding practice variables are likely to reduce the risk of child stunting (S1). We used four binary (yes or no) predictors to represent feeding practices at birth, birth to 6 months, 6 to 8 months, 12 months: initiation of breastfeeding within 24 h after delivery, consistent breastfeeding for 6 months after birth, complementary between 6 and 8 months, and breastfeeding at 12 months. Our operational definition is adapted from the indicators set by the WHO to assess infant feeding practices25.

Among feeding practice predictors, only breastfeeding at 12 months and complementary feeding were simultaneously analysed as mediators in the models. Initiation of breastfeeding and consistent breastfeeding have null effects to stunting and weak associations with repeated pregnancy which disqualify these variables for mediation testing26. We used the binary_mediation macro to perform mediation analysis with regression coefficients bootstrapped in 10,000 simulations to obtain robust confidence intervals at 0.05 level of error. This macro adapted the standard Baron and Kenny set of equations to handle binary mediators in our study for continuous and discrete outcomes27. Mediated effects of birthweight and feeding practices will be estimated as a proportion by dividing the total indirect effects by the total effect28.

All analyses were performed using Stata 14.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from study participants. This study was conducted in accordance with the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines, the guiding principles for ethical research of the US National Institutes of Health, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

This study was approved by The University of Queensland School of Public Health Ethics Committee on April 11, 2016. The conduct of the CLHNS surveys were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 1,033 mother–offspring dyads had complete LAZ data at both 12- and 24-month follow-ups. This consists of 299 14–19 year old and 734 20–24-year-old eligible women, most were unemployed (n = 629, 60.8%), did not completed high school (n = 826, 80.0%), and were from middle income class (n = 646, 62.6%) (refer to Table 1). Approximately 40% of the 14–19 year olds and 70% of 20–24-year olds had ≥ 1 pregnancy prior to the index child. More than half of young mothers had consistently breastfed until 6 months (n = 576, 55.8%) while almost all had provided complimentary feeding between 6 and 8 months to the index child (n = 996, 96.5%).

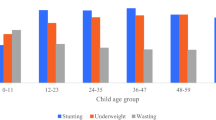

Compared to offspring of 20–24-year-old women, offspring of 14–19 year olds showed lower average LAZ and higher stunting prevalence both at 12 and 24 months. Children of 14–19 year olds demonstrated an average LAZ of − 1.79 [Standard Deviation (SD) = 1.1] at 12 months and − 2.43 (SD = 1.1) at 24 months; and stunting prevalence of 39.1% and 63.3% at 12 and 24 months respectively. More than a third of the offspring sample showed persistent stunting from 12 through to 24 months of age. These estimates were elevated in reference to the overall values.

Prevalence of stunting

Offspring of young mothers with repeated pregnancies (i.e. with at least one past pregnancy) showed a higher prevalence of stunting and lower mean LAZ compared with offspring of mothers with no past pregnancies (Fig. 1). There was a large difference in mean LAZ: from − 1.53 (95% CI − 1.64, − 1.41) among offspring of mothers with no past pregnancies to − 2.09 (95% CI − 2.30, − 1.89) among offspring of mothers with ≥ 3 pregnancies at 12 months and; from − 2.10 (95% CI − 2.18, − 1.97) among offspring of mothers with no past pregnancies to − 2.77 (95% CI − 2.98, − 2.59) among offspring of those with ≥ 3 pregnancies at 24 months. We also found that LAZ is slightly lower and stunting prevalence is slightly higher in the 14–19 age group than in the 20–24 age group, particularly at 24 months (S2).

Occurrence and persistence of stunting among young mothers with repeated pregnancies

Young mothers (14–24 years old) who experienced repeated pregnancies were more likely to have stunted offspring at 12 and 24 months (Table 2). Offspring from a repeated pregnancy showed 40% (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.19, 1.67) increased odds at 12 months and 25% (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.04, 1.50) increased odds to be stunted at 24 months. The LAZ at 12 and 24 months in offspring of mothers who had experienced repeated pregnancies was at least 0.15 LAZ units lower compared to those of mothers who had had no previous pregnancies. We also observed a high risk of stunting persistence from 12 to 24 months. Subsequent offspring showed 1.51 times the risk of persistent stunted growth (Relative Risk Ratio 1.51, 95% CI 1.21, 1.88) compared with offspring born to first time mothers.

We found null interactions by maternal age, which suggests no substantive difference between the risk of offspring stunting in women aged 14–19 and 20–24 years (S3). This was also confirmed by similar effect estimates and prevalence differences across number of past pregnancies for each age group.

Low birthweight, introduction of semi-/solid foods between 6 and 8 months (or complimentary feeding) and breastfeeding at 12 months have consistently demonstrated strong association with LAZ and stunting occurrence at 12 and 24 months (see Table 2). These associations were also observed among those who had persistent offspring stunting at both time points.

Repeated pregnancy and stunting via low birthweight and feeding practice

After confirming a direct effect of repeated pregnancy among young mothers on offspring stunting, we conducted a series of regression analyses to test for mediation via low birthweight and feeding practice predictors. Mediator feeding practices included breastfeeding at 1 year and complementary feeding due to their consistent associations with stunting outcomes. Mediating effects showed that repeated pregnancy via low birthweight decreased LAZ by 0.16 units (95% CI − 0.24, − 0.08) at 12 months and 0.15 units (95% CI − 0.22, − 0.07) at 24 months (Table 3). Analysis using binary stunting outcomes showed that mediation via optimal feeding practices reduced the effects of repeated pregnancy. This is equivalent to 13.66% and 19.95% mediation via feeding practices for stunting occurrence at 12 and 24 months. We only analysed mediation for ‘persistent’ stunting outcome due to the null effects of repeated pregnancy, low birthweight and feeding practices to ‘late incident’ and ‘recovered’ stunting as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

Our study produced robust estimates to show that repeated pregnancy is a predictor for stunting. Our finding contributes to strengthening the limited evidence on the impact of repeated pregnancy as a predictor of child health, with a particular focus on evidence from low- and middle-income countries29. We found that children of young mothers with repeated pregnancy are at increased stunting occurrence before the age of two compared to first-time young mothers.

In addition to stunting occurrence at two separate time points, subsequent children also showed higher risk of persistent stunting from 12 to 24 months. This is of particular concern if one considers that children commonly have their best chance of recovering from stunting within the first 2 years of life18. Our findings on persistence of stunting during the first 2 years of life is supported by a cross-sectional analysis of 18 countries conducted by United Nations Children’s Fund which showed an increased prevalence and reduced LAZ at 0–11 and 12–23 months among offspring of 15–19 year old mothers30. Another multi-country analysis of five cohort studies in developing countries found similar results in its preliminary analysis; a decline in offspring’s LAZ at 2 years by parity10. A multi-level meta-analysis also found repeated pregnancies influence delayed infant growth31.

The impact of repeated pregnancy on stunting can be explained by the ‘dual-developmental crisis’ experienced by young mothers during their repeated conceptions32, 33. The ongoing nutritional requirement of young mothers due to puberty may deplete foetal nutrition causing low birthweight34 which we also found to be strongly associated with stunting in our study. Occurrence of another pregnancy may also disrupt young women’s psychosocial adaptation, which may in turn result in poor health-seeking behaviour on pregnancy nutrition35, poor infant feeding practices, and food insecurity within the household36. Because repeated pregnancies are often unintended37, young women may also be at risk of multiple psychosocial disadvantage including educational disruption, inadequate socio-economic resources, and poor human capital36. It has also been suggested that maternal inexperience, absence of autonomy, and poor hygiene may lead to suboptimum feeding, a precursor to stunting in offspring10.

As mediators, low birthweight and poor feeding practices further increased the harmful effect of repeated pregnancy on infants’ growth. Prevention and mitigation programs, especially in the first 1,000 days, are essential to revert these health and social burdens. Addressing low birthweight and suboptimal feeding practices, which are empirically identified in this study as mediators, may show promise for interventions and ultimately improve offspring’s growth trajectories. Improving young women’s access to modern contraception may also contribute to reduced stunting among their first and subsequent children38.

Our study adds to the existing literature through a rigorous method which allowed us to investigate this problem by accounting for the effects of important confounders and by exploring mediators with practical implications. Our study also has some limitations. Our models could not account for potential mediator-outcome confounders such as maternal nutritional intake from diet and supplements, as well as other psychosocial factors. Adjusting for these confounders would further reduce the residual errors and improve the certainty of regression coefficients. We were also unable to dissect feeding practice in terms of timing, amount, frequency, and diversity of solid food introduced which would allow this mediator to better inform promotion strategies. Further, we were not able to account for residual biological confounders which can be addressed through a comparative cluster analysis between the first and second child from a young mother.

Repeated pregnancy in young mothers is a predictor of child stunting. Children of young mothers with repeated pregnancies showed persistent stunting from 1 to 2 years of age which was substantially worsened by low birthweight and suboptimal feeding practices. Further research is needed to investigate and establish causal pathways and trajectories, which may clarify the unique pathogenesis of child stunting among young mothers.

Data availability

The data can be freely accessed through this link: https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/cebu/datasets.

References

Borghi, E., Casanovas, C. & Onyango, A. WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Stunting Policy Brief (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2017).

Black, R. E. et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 382, 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X (2013).

de Onis, M. & Branca, F. Childhood stunting: a global perspective. Matern. Child Nutr. 12(1), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12231 (2016).

Georgiadis, A. & Penny, M. E. Child undernutrition: opportunities beyond the first 1000 days. Lancet Public Health 2, e399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30154-8 (2017).

Prendergast, A. J. & Humphrey, J. H. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 34, 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1179/2046905514Y.0000000158 (2014).

Keusch, G. T. et al. Implications of acquired environmental enteric dysfunction for growth and stunting in infants and children living in low- and middle-income countries. Food Nutr. Bull. 34, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651303400308 (2013).

Nguyen, P. H. et al. The nutrition and health risks faced by pregnant adolescents: insights from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 12, e0178878. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178878 (2017).

Das, J. et al. Nutrition in adolescents: physiology, metabolism, and nutritional needs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1393, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13330 (2017).

King, J. C. The risk of maternal nutritional depletion and poor outcomes increases in early or closely spaced pregnancies. J. Nutr. 133, 1732S-1736S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.5.1732S (2003).

Fall, C. H. D. et al. Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: a prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (COHORTS collaboration). Lancet Glob. Health 3, e366–e377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00038-8 (2015).

Qu, P. et al. Association between the Infant and Child Feeding Index (ICFI) and nutritional status of 6- to 35-month-old children in rural western China. PLoS ONE 12, e0171984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171984 (2017).

Philippine Statistics Authority & and ICF International. Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2013 2014 (Philippine Statistics Authority, and ICF International, Manila, 2013).

Capanzana, M. V., Aguila, D. V., Javier, C. A., Mendoza, T. S. & Santos-Abalos, V. M. Adolescent pregnancy and the first 1000 days (the Philippine Situation). Asia Pac J. Clin. Nutr. 24, 759–766. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.4.07 (2015).

World Health Organisation. Adolescence: A Period Needing Special Attention (World Health Organisation, Geneva, 2014).

Adair, L. S. et al. Cohort profile: the Cebu longitudinal health and nutrition survey. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq085 (2011).

Maravilla, J. C., Betts, K. S. & Alati, R. Trends in repeated pregnancy among adolescents in the Philippines from 1993 to 2013. Reprod. Health 15, 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0630-4 (2018).

Ogbo, F. A., Ogeleka, P. & Awosemo, A. O. Trends and determinants of complementary feeding practices in Tanzania, 2004–2016. Trop. Med. Health 46, 40–40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-018-0121-x (2018).

Adair, L. S. & Guilkey, D. K. Age-specific determinants of stunting in Filipino children. J. Nutr. 127, 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/127.2.314 (1997).

Habicht, J.-P., Butz, W. P., Pradilla, A., Fajardo, L. F. & Acciarri, G. In Evaluating the Impact of Nutrition and Health Programs (eds Klein, R. E. et al.) 133–182 (Springer, Berlin, 1979).

World Health Organisation. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2006).

Vidmar, S. I., Cole, T. J. & Pan, H. Standardizing anthropometric measures in children and adolescents with functions for egen: Update. Stata J. 13, 366–378 (2013).

Mendez, M. A. & Adair, L. S. Severity and timing of stunting in the first two years of life affect performance on cognitive tests in late childhood. J. Nutr. 129, 1555–1562 (1999).

Solon, O. & Floro, M. The Philippines in the 1980s: A Review of National and Urban Level Economic Reforms (World Bank, Washington, DC, 1993).

Albert, J. R. G., Gaspar, R. E. & Raymundo, M. J. M. Why We Should Pay Attention to the Middle Class? (Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Philippines, 2015).

World Health Organisation. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Conclusions of a Consensus Meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA (World Health Organisaiton, Geneva, 2007).

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J. & Fritz, M. S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58, 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 (2007).

Wiles N, T. L., Abel A, et al. in Health Technology Assessment Vol. 18.31 Ch. Chapter 9, Mediated effect of cognitive behavioural therapy on depression outcomes (NIHR Journals Library, 2014).

How can i perform mediation with binary variables? https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stata/faq/how-can-i-perform-mediation-with-binary-variables/. Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Fenske, N., Burns, J., Hothorn, T. & Rehfuess, E. A. Understanding child stunting in India: a comprehensive analysis of socio-economic, nutritional and environmental determinants using additive quantile regression. PLoS ONE 8, e78692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078692 (2013).

Yu, S. H., Mason, J., Crum, J., Cappa, C. & Hotchkiss, D. R. Differential effects of young maternal age on child growth. Glob. Health Act. 9, 31171. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.31171 (2016).

Danaei, G. et al. Risk factors for childhood stunting in 137 developing countries: a comparative risk assessment analysis at global, regional, and country levels. PLoS Med. 13, e1002164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002164 (2016).

Sadler, L. S. & Catrone, C. The adolescent parent: a dual developmental crisis. J. Adolesc. Health Care 4, 100–105 (1983).

Wu, G., Bazer, F. W., Cudd, T. A., Meininger, C. J. & Spencer, T. E. Maternal nutrition and fetal development. J. Nutr. 134, 2169–2172. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/134.9.2169 (2004).

Borja, J. B. & Adair, L. S. Assessing the net effect of young maternal age on birthweight. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 15, 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.10220 (2003).

Stephenson, T. & Symonds, M. E. Maternal nutrition as a determinant of birth weight. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 86, F4. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.86.1.F4 (2002).

United Nations Children’s Fund. Improving Child Nutrition: The Achievable Imperative for Global Progress (United Nations Children’s Fund, New York, 2013).

Aslam, R. H. W. et al. Intervention now to eliminate repeat unintended pregnancy in teenagers (INTERUPT): a systematic review of intervention effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and qualitative and realist synthesis of implementation factors and user engagement. BMC Med. 15, 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0904-7 (2017).

Finlay, J. E. The association of contraceptive use, nonuse, and failure with child health. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 1, 113–134 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr Sean Mitchell and Dr Jennifer Juckel for language editing. This paper was presented in the 17th National Health Research for Action Forum, Philippines, October 2018. An initial version of this manuscript was published as part of JCM’s thesis which can accessed using this link: https://doi.org/10.14264/uql.2019.468.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.M. conceptualized the study design; conducted data extraction, analysis and interpretation; drafted the initial manuscript, coordinated revision of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission. K.B. contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission. L.A. collected the data, contributed to the study design and reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission. R.A. significantly contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maravilla, J.C., Betts, K., Adair, L. et al. Stunting of children under two from repeated pregnancy among young mothers. Sci Rep 10, 14265 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71106-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71106-7