Abstract

We solve the quasi-bound state-energy spectra and wavefunctions of an NPN-type graphene quantum dot under a perpendicular magnetic field. The evolution of the quasi-bound state spectra under the magnetic field is investigated using a Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin approximation. In numerical calculations, we also show that the twofold energy degeneracy of the opposite angular momenta breaks under a weak magnetic field. As the magnetic field strengthens, this phenomenon produces an observable splitting of the energy spectrum. Our results demonstrate the relation between the quasi-bound state-energy spectrum in graphene quantum dots and magnetic field strength, which is relevant to recent measurements in scanning tunneling microscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene has promising prospects in condensed matter physics owing to its extraordinary properties, such as Klein tunneling, Zitterbewegung motion, and minimum quantum conductance1,2,3,4. These properties allow the investigation and realization of exotic relativistic quantum phenomena3. Although Klein tunneling precludes the capture of relativistic quasi-particles in graphene, the energy barrier in graphene nano-structures such as PN junctions can induce quasi-bound states with finite lifetimes5. Quasi-bound states in graphene quantum dots and other graphene constrained systems have been prominently studied in theoretical works5,6,7,8,9, and experiments10,11,12,13,14. For example, the found quasi-bound states are related to the atomic collapse states that have been found for the Coulomb problem15,16,17.

The quantum Hall effect in graphene systems under a magnetic field has been widely studied recently. Meanwhile, in graphene quantum dots under a magnetic field, the quasi-bound states coexist with the magnetic field, resulting in interesting physical phenomena. Thus far, graphene quantum dots under magnetic fields have been studied in previous works18,19,20,21,22, however qualitative semi-classical and numerical analyses can help us to interpret the energy spectra and physical properties of graphene quantum dots under magnetic fields more completely.

In this paper, we study the wavefunction, local density of states (LDOS) and energy spectrum of an NPN-type circular graphene quantum dot under a magnetic field. The numerical results are based on the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) approximation. Comparing the zero-field results of the WKB approximation with rigorous analytical results, we find energy degeneracy in the opposite angular momenta. Next, the energy spectra under different magnetic fields are obtained by the WKB approximation. Increasing the magnetic field breaks the energy degeneracy of the opposite angular momenta, leading to increasingly obvious splitting in the spectrum. This LDOS splitting is also observable in experiments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we model a graphene quantum dot under a magnetic field by the Dirac equation and numerically solve the wavefunction and quasi-bound states spectrum by the WKB approximation. The analytical solution without a magnetic field is also presented. After evolving the energy spectrum under a magnetic field, we conclude the study and highlight its relevance to recent experiments.

Modeling and radial function

We consider an NPN-type graphene quantum dot in a perpendicularly upward homogeneous magnetic field. The Dirac equation of this system is given by23,24,25:

where the Fermi velocity is set to \(v_{F} = 1\), and \(\sigma _{\mu }\) is the Pauli matrices. Fig. 15,6,8,11 shows the centrally symmetric step potential V(r) generated in the NPN-type circular graphene quantum dot:

where R is the radius of the graphene quantum dot, \(P_{\mu }\) is the generalized momentum, and \(A_{\mu }\) is the vector potential generated by the perpendicular magnetic field B along the z-axis, calculated as \(A_{x}=-\frac{By}{2},A_{y}=\frac{Bx}{2}\).

The wavefunction is assumed as \( \psi (r,\varphi ,t)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }}e^{-iEt/\hbar }\psi _{l}(r,\varphi ), \) where \(E=E_{F}-E_{D}\) is the difference between the Fermi energy \(E_{F}\) and the Dirac-point energy \(E_{D}\). The eigenfunction of the total angular momentum l takes the form:

where l is the angular momentum quantum number. Further, using \( P_{x}\pm iP_{y}=-ie^{\pm i\varphi }[\hbar \partial _{r}\pm (\frac{i\hbar }{r}\partial _{\varphi }-\frac{eBr}{2})], \) the equation can be recast as

In the next section, we solve the coupled differential equations in Eqs. (4) and (5) using the WKB approximation.

WKB solutions in the presence and absence of a magnetic field

WKB approximation

In the absence of a magnetic field, the energy spectra of a disc can be accurately described by the Bessel function11; however, finding the rigorous solution of a graphene quantum dot under a magnetic field is considerably difficult. Thus, we apply the WKB approximation26 to a quantum dot under a magnetic field. To obtain the WKB form, we substitute \((l+\frac{1}{2})\hbar \) in Eqs. (4) and (5) by \(m\equiv l+\frac{1}{2} =\pm \frac{1}{2},\pm \frac{3}{2},\pm \frac{5}{2}\cdots \) and retain the \(\hbar \) in front of the differential sign as the expansion parameter27. In matrix form, this becomes

where

We then suppose

in which \(\beta (r)\) is the difference factor between the upper- and lower-component wavefunctions, and y(r) is the local phase28. Writing y(r) as a Taylor expansion

the solution reads

in which

The detailed derivation from Eqs. (4) and (5) to Eq. (13) is given in Part 1 of the supplementary material. Finally, the phase function is obtained by integration, retaining the terms up to order \(\hbar \):

The radial wave function can then be written as

where \({\mathcal {C}}\) is the normalization factor.

Effective potential and quasi-bound states

In the following, we set \(\hbar =1\) for convenience. To consider the effective momentum, we state \(q^2=-U_{\mathrm {eff}}+E_{\mathrm {eff}}\) and \(\tilde{q}^2=U_{\mathrm {eff}}-E_{\mathrm {eff}}\), where \(E_{\mathrm {eff}}=E^2\) is the effective energy and \(U_{\mathrm {eff}}(r,E)=2EV(r)-V^2(r)+(\frac{m}{r}+\frac{eBr}{2})^2\) is the effective potential. Figure 2a shows that the side view of a graphene quantum dot can be divided into four regions along the r axis: I (inside), II (inside), III (outside), and IV (outside). Based on the relation between \(U_{\mathrm {eff}}\) and \(E_{\mathrm {eff}}\), we can also distinguish four situations as shown in Table 1.

(a) Effective energy \(E_{eff}\)(blue curve) and effective potential \(U_{eff}\)(red curve) of a graphene quantum dot with radius R. The plot can be divided into four regions along the r axis (I, II, III, and IV), in which the quasi-bound states exist in region II. Panels (b–d) plot the \(r_{-}\) versus B relations for \(m=\pm 1/2, \pm 3/2, and \pm 5/2, respectively (R = 4 \mathrm {nm}\)). These plots are related to the width of the energy spectrum. The corresponding quasi-bound states become bound states when B exceeds the critical magnetic field strength \(B_{c}\) (\(B_{c}\mid _{m=1/2}\approx 1.1 \mathrm {T}\) for m=1/2; in the higher angular momentum channels, we obtain \(B_{c}\mid _{m=3/2}\approx 28 \mathrm {T} and B_{c}\mid _{m=5/2}\approx 66 \mathrm {T}\)).

This paper focuses only on situation (2), which accommodates quasi-bound states. In situation (2), the turning points \(r_{+}\) and \(r_{-}\) at which \(U_{\mathrm {eff}}=E_{\mathrm {eff}} \) are correspondingly given by

Panels (b), (c), and (d) of Fig. 2 plot the dependences of \(r_{-}\) on B for \(m=\pm 1/2, \pm 3/2, and \pm 5/2\), respectively, with \(R=4 \mathrm {nm}\).

The wavefunction in the classical allowed region II then follows from Eqs. (15) and (16):

where N is the normalization factor, and the phase factor \(\frac{i\pi }{4}\) is obtained by the Airy function.

In the classical forbidden regions I and III in Fig. 2a, the wavefunction damps exponentially. The radial wavefunction inside the quantum dot can be written as

The functions \(F_{I}(r)\) and \(G_{I}(r)\) in Eq. (21) are given in Part 2 of the Supplementary Material. The radially-averaged LDOS is \(|\psi _{m}^{in}|^2\).

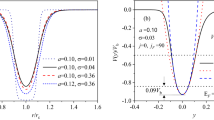

LDOS and energy spectra of quasi-bound states calculated by the WKB approximation. The quasi-bound energy levels of the \(m=\pm 1/2,\pm 3/2, and \pm 5/2 \ldots \) states of the graphene quantum dot with \(R=4 nm,\,V_0=0.42 eV,\,E_{D}=-0.09 eV\) depend on the magnetic field strength B. Panels (a)–(f) show the WKB-approximated LDOS inside the graphene quantum dot under different B fields: (a) \(m=\pm 1/2,B=0\), (b) \(m=\pm 1/2,B=1 \mathrm {T}\), (c) \(m=\pm 3/2,B=0\), (d) \(m=\pm 3/2,B=10 \mathrm {T}\), (e) \(m=\pm 5/2,B=0\), and (f) \(m=\pm 5/2,B=15 \mathrm {T}\). Panel (g) plots the peak values in the energy spectra as B changes from 0 to \(30 \mathrm {T},m=\pm 1/2,\pm 3/2, and \pm 5/2\).

At this time, the relation between the angular momentum number m and the peak energies of the quasi-bound states can be determined by the quantization rule, explicitly given by

where \(q_{0m,n}(r)\) and \(q_{1m,n}(r)\) are the functions of the quasi-bound states energy \(E_{n,m}\). They are defined by Eqs. (10) and (12), respectively. By applying the quantization rule to Eq. (21), we obtain the relation between \(E_{n,m}\) and the quantum number n, which can be interpreted as the radial quantum number. \(\theta \in (0,\pi )\) is determined by n, m, and R (actually, it largely depends on the shape of \(U_{eff}\), which is also related to m, n, and R)29.

The width \(\Gamma _{m,n}\) of the energy spectrum in the quasi-stationary state is obtained as27

where \(r_{+m,n}\) and \(r_{-m,n}\) are determined by Eqs. (17) and (18), respectively, \(E=E_{n,m}\), \(\tilde{q}_{0m,n}(r)\), and \(\tilde{q}_{1m,n}(r)\) are momenta in the classical forbidden region, as defined by Eq. (S.9) of the supplementary material. The broadening effect mainly originate from the Klein tunneling of Dirac particle. Thus, in our system, the quasi-bound states in the central region have finite life time due to the Klein tunneling, in other words, such quasi-bound state can be called a resonance state.

The above analysis refers to situation (2). When \(E^2\le 2eBm\), B reaches the critical magnetic field strength \(B_{c}=\frac{E^2}{2em}\) (obtained by rearranging Eq. (18)). The situation then transitions from situation (2) to situation (3), in which the quasi-bound states become bound states. Notably, \(B_{c}\) and m have the same sign; thus, when the magnetic field points upward along the z-direction, \(B_{c}\) exists only when \(m>0\).

Evolution of LDOS for different angular momenta. Increasing the magnetic field breaks the energy-level degeneracy of the NPN-type graphene quantum dot. Rows (A)–(D) show the three-dimensional LDOS maps of the graphene quantum dot with \(R=4 nm,\,V_0=0.42 eV, and \,E_{D}=-0.09 eV\) under different magnetic field strengths: (A) \(m=1/2,\, B=0,0.5,1 \mathrm {T}\, (B_{c}|_{m=1/2}\approx 1.1 \mathrm {T})\) , (B) \(m=-1/2,\, B=0,1,5 \mathrm {T}\,(\)no \( B_{c}|_{m=-1/2}\)), (C) \(m=3/2,\, B=0,15,28 \mathrm {T} \, (B_{c}|_{m=3/2}\approx 28.2 \mathrm {T})\), and (D) \(m=-3/2,\, B=0,15,28 \mathrm {T}\,(\)no \( B_{c}|_{m=-3/2}) .\) When \(m>0\), the energy level shifts in the negative direction and becomes narrower; when \(m>0\), it moves in the positive direction and widens.

In the following section, we analyze the relation between the energy \(E_{0,m}\) of the quasi-bound states and the angular momentum m for the case \(n=0\).

Numerical results and discussion

In the absence of a magnetic field, the analytical wavefunction of a quasi-bound state with angular momentum m is given by11:

The transmissivity is

where \(q=(E-V_{0})/\hbar ,\;k=E/\hbar \;(v_{F}=1)\), \(J_{m\pm \frac{1}{2}}\) is the Bessel function of the first kind, and \(H^{(1)}_{m\pm \frac{1}{2}}\) is the Hankel’s function of the first kind. The LDOS inside the graphene quantum dot with no magnetic field is then obtained by noting that \(|\psi _{m}^{in}{\varvec{|}}_{B=0,rigorous}|^{2}\varpropto \mathrm {LDOS}(r,E)\).

Notably, for graphene quantum dots without a magnetic field, the spectra of the step-potential and smooth-potential systems share the same features30. A comparison of WKB solution and the exact solution when \(B=0\) is presented in the Part 3 of the supplementary material. Furthermore, we consider the LDOS and energy spectrum for \(B\ne 0\). The solution can be obtained by Eqs. (21) and (22), and the phase shift \(\theta \) is determined by comparing the WKB-approximated energy level at \(B=0\) with the analytical solution at \(B=0\). Panels (a)–(f) of Fig. 3 show the quasi-bound energy levels of \(m=\pm 1/2, m=\pm 3/2, and m=\pm 5/2\) as the magnetic field B changes from 0 to \(30 \mathrm {T}\) upward along the z-axis. The other parameters are \(R=4 nm,\,V_0=0.42 eV,\, E_{F}=E+E_{D},\, and E_{D}=-0.09 eV\). Increasing B along the z-axis relieved the degeneracy of \(\pm m\): for \(m>0\), the energy levels \(E_{n,m}\) reduced and the bandwidths become increasingly acute until B exceeded \(B_{c}\); for \(m<0\), the energy levels \(E_{n,m}\) enlarged and the bandwidths broadened. Fig. 3(g) provides the evolutionary processes of the energy levels as the magnetic field B varied. For a given magnetic field strength, increasing the \(\mid m\mid \) yielded a more remarkable change in \(E_{n,m}\).

Using the results of Fig. 3, Eqs. (21), and (22), we can obtain the transmittance of the graphene quantum dot under a magnetic field. Considering the transmittance as the initial value of the evolution at \(r=R\), and applying Eqs. (4) and (5) as the radial evolution equations, we obtained the three-dimensional radial-energy-transmittance LDOS map of the graphene quantum dot under a magnetic field. The results are shown in Fig. 4, which directly reveals the main energy-evolution features in the quasi-bound state of the NPN-type graphene quantum dot under a perpendicular magnetic field: As shown in Fig. 4A and B, the energy degeneracy at \(\pm m\) and \(B=0\) was relieved at larger B. When \(m=3/2\), the quasi-bound state energy moved in the negative direction and exhibited sharp resonances at magnetic field strengths above \(B_{c}\mid _{m=3/2}\approx 28.2 \mathrm {T}\). Meanwhile, when \(m=-3/2\), the energy shift in the quasi-bound state was positive and the energy levels broadened. The evolution of the quasi-bound energy level \(E_{m,n}\) depends on the quantization rule given by Eq. (21), and \(r_{-}\) is responsible for the energy width \(\Gamma _{m,n}\) as shown in Eq. (22). Both of these restriction conditions depend on the magnetic strength B. The LDOS at \(m=\pm 1/2\) and \(m=\pm 3/2\) exhibited similar features, and \(B_{c}\mid _{m=1/2} \approx 1.1 \mathrm {T}\) (see Fig. 4 (C), (D)). Moreover, enlarging the |m| broadened the energy spectrum by bringing the effective energy closer to the top of the effective potential barrier, thereby increasing the critical magnetic field.

Conclusion

This paper discussed the evolution of the quasi-bound energy spectrum of an NPN-type graphene quantum dot under a perpendicular magnetic field. The wavefunction was approximately solved using the WKB method. The magnetic field broke the twofold degeneracy of \(\pm m\), thereby splitting the energy spectrum and inducing sharp resonances at higher magnetic strengths. The numerical results are relevant to recent experimental results14,31. Our method can effectively reveal the evolution of the quasi-bound states in graphene quantum dots placed in magnetic fields.

References

Katsnelson, M. I., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. Chiral tunnelling and the klein paradox in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2(9), 620 (2006).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6(3), 183 (2007).

Katsnelson, M. I. Graphene: Carbon in Two Dimensions. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012).

Xiao, Di., Yao, Wang & Niu, Qian. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99(23), 236809 (2007).

Matulis, A. & Peeters, F. M. Quasibound states of quantum dots in single and bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 77(11), 115423 (2008).

Bardarson, J. H., Titov, M., & Brouwer P. W. Electrostatic confinement of electrons in an integrable graphene quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett., 102(22):226803, (2009).

Downing, C. A., Stone, D. A. & Portnoi, M. E. Zero-energy states in graphene quantum dots and rings. Phys. Rev. B 84(15), 155437 (2011).

Wu, J.-S. et al. Scattering of two-dimensional massless dirac electrons by a circular potential barrier. Phys. Rev. B, 90(23):235402 (2014).

Bacon, M., Bradley, S. J. & Nann, T. Graphene quantum dots. Particle Particle Syst. Charact. 31(4), 415–428 (2014).

Zhao, Y., Wyrick, J., Natterer, F. D., Rodriguez-Nieva, J. F., Lewandowski, C., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., Levitov, L. S., Zhitenev, N. B., & Stroscio, J. A. Creating and probing electron whispering-gallery modes in graphene. Science, 348(6235):672–675 (2015).

Gutiérrez, C., Brown, L., Kim, C.-J., Park, J., & Pasupathy, A. N. Klein tunnelling and electron trapping in nanometre-scale graphene quantum dots. Nat. Phys., 12(11):1069, (2016).

Lee, J., Wong, D., Velasco Jr, J., Rodriguez-Nieva, J. F., Kahn, S., Tsai, H.-Z., Taniguchi, T., Watanabe, K., Zettl, A., Wang, F. et al. Imaging electrostatically confined dirac fermions in graphene quantum dots. Nat. Phys., 12(11):1032 (2016).

Yin, L.-J., Jiang, H., Qiao, J.-B. & He, L. Direct imaging of topological edge states at a bilayer graphene domain wall. Nat. Commun. 7, 11760 (2016).

Bai, Ke.-Ke., Qiao, Jia-Bin., Jiang, Hua, Liu, Haiwen & He, Lin. Massless dirac fermions trapping in a quasi-one-dimensional npn junction of a continuous graphene monolayer. Phys. Rev. B 95(20), 201406 (2017).

Mao, J., Jiang, Y., Moldovan, D., Li, G., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., Masir, M. R., Peeters, F. M., & Andrei, E. Y. Realization of a tunable artificial atom at a supercritically charged vacancy in graphene. Nat. Phys., 12(6):545, (2016).

Jiang, Y., Mao, J., Moldovan, D., Masir Massoud Ramezani, L., Guohong, W., Kenji, T., Takashi, P., Francois M., & Andrei, E. Y. Tuning a circular p–n junction in graphene from quantum confinement to optical guiding. Nat. Nanotechnol., 12(11):1045, (2017).

Moldovan, Dean, Masir, M Ramezani, & Peeters, Francois M. Magnetic field dependence of the atomic collapse state in graphene. 2D Mater., 5(1):015017, (2017).

De Martino, A. & Egger, R. On the spectrum of a magnetic quantum dot in graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25(3), 034006 (2010).

Kuru, Ş, Negro, J. & Sourrouille, L. Confinement of dirac electrons in graphene magnetic quantum dots. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30(36), 365502 (2018).

Recher, Patrik, Nilsson, Johan, Burkard, Guido & Trauzettel, Björn. Bound states and magnetic field induced valley splitting in gate-tunable graphene quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 79(8), 085407 (2009).

Da Costa D.R., Zarenia, M., Chaves, Andrey, Farias, G.A., & Peeters, F.M. Magnetic field dependence of energy levels in biased bilayer graphene quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B, 93(8):085401, (2016).

Wang, Dali & Jin, Guojun. Bound states of dirac electrons in a graphene-based magnetic quantum dot. Phys. Lett. A 373(44), 4082–4085 (2009).

Landau, L.D., & Lifshitz, E.M. Course of Theoretical Physics, vol. 3: Quantum Mechanics: Non-relativistic Theory, Fizmatlit, Moscow, 2001 (Pergamon, New York, 1977).

Sakurai, J. J., Commins, J. & Eugene D. Modern Quantum Mechanics, Revised Edition (1995).

Ho, Choon-Lin. & Khalilov, V. R. Planar dirac electron in coulomb and magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. A 61(3), 032104 (2000).

Marinov, M. S. & Popov, V. S. Variant of the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin Method and Calculation of the Critical Nuclear Charge (Inst. of Theoretical and Experimental Physics, Moscow, Technical report, 1974).

Rubish, V. V., Yu Lazur, V., Reity, O. K., Chalupka, S. & Salak, M. The wkb method for the dirac equation with the vector and scalar potentials. Czech. J. Phys. 54(9), 897–919 (2004).

Van Orden, J.W., Jeschonnek, S., & Tjon, J. Scaling of dirac fermions and the wkb approximation. Phys. Rev. D, 72(5):054020, (2005).

Mur, V. D. & Popov, V. S. The wkb method for resonances. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz 104, 2293–2313 (1993).

Zhou, JiaoJiao, Cheng, ShuGuang, You, WenLong & Jiang, Hua. Numerical study of klein quantum dots in graphene systems. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 62(6), 67811 (2019).

Fu, Zhong-Qiu, Pan, Yue-Ting, Zhou, Jiao-Jiao, Ma, Dong-Lin, Zhang, Yu, Qiao, Jia-Bin, Haiwen Liu, Jiang, Hua, & He, Lin, Relativistic artificial molecules realized by two coupled graphene quantum dots. arXiv:1908.06580, (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Lin He and Hua Jiang for helpful discussions and Lin He and Zhongqiu Fu for showing their unpublished experimental data. This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grants No. 2017YFA0303301 and No. 2017YFA0303304) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11674028, No. 11534001, and No. 11675016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P. performed the analytic calculations and numerical simulations and also wrote the manuscript, with the assistance of H.J.; H.L. supervised the calculation and writing of the article; X.-Q.L. provided comments and suggestions in the whole process of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Y., Ji, H., Li, XQ. et al. Quasi-bound states in an NPN-type nanometer-scale graphene quantum dot under a magnetic field. Sci Rep 10, 20426 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77357-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77357-8

This article is cited by

-

Effects of Aharonov–Bohm flux and gap on graphene quantum dots in magnetic field

Applied Physics A (2024)

-

Recent progresses of quantum confinement in graphene quantum dots

Frontiers of Physics (2022)