Abstract

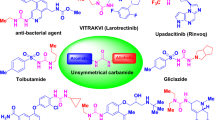

Three new compounds (1–3) with unusual skeletons were isolated from the n-hexane extract of the air-dried aerial parts of Hypericum scabrum. Compound 1 represents the first example of an esterified polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol that features a unique tricyclo-[4.3.1.11,4]-undecane skeleton. Compound 2 is a fairly simple MPAP, but with an unexpected cycloheptane ring decorated with prenyl substituents, and compound 3 has an unusual 5,5-spiroketal lactone core. Their structures were determined by extensive spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques (1D and 2D NMR, HRESI-TOFMS). Absolute configurations were established by ECD calculations, and the absolute structure of 2 was confirmed by a single crystal determination. Plausible biogenetic pathways of compounds 1–3 were also proposed. The in vitro antiprotozoal activity of the compounds against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and Plasmodium falciparum and cytotoxicity against rat myoblast (L6) cells were determined. Compound 1 showed a moderate activity against T. brucei and P. falciparum, with IC50 values of 3.07 and 2.25 μM, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypericum perforatum has gained great attention in the scientific community due to its high economic value, and prompted detailed phytochemical investigation into other Hypericum species1,2. The Hypericum genus belonging to the Hypericaceae family with a wide distribution in temperate regions has been utilized in folk medicine of different parts of the globe1,3,4. These plants are known to include several types of compounds such as prenylated acylphloroglucinols, terpenoids, flavonoids, xanthones, naphtodianthrones5,6, and some spiro compounds including spiroterpenoids7, spirolactones8, polyprenylated spirocyclic acylphloroglucinols9, and spiroketals10. These metabolites are also reported to display a wide range of pharmacological properties including antimicrobial, antitumor, antioxidant, anti-HIV, and antidepressant activities11,12,13.

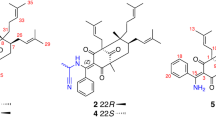

Hypericum scabrum has been used in Iranian folk medicine as an antiseptic, analgesic, sedative, and for treating headaches14. Prior phytochemical and pharmacological investigations into this species have demonstrated that the plant is rich in secondary metabolites, especially polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols (PPAPs)15,16,17,18. PPAPs are a class of synthetically challenging and structurally attractive natural compounds having an acylphloroglucinol-derived core modified with prenyl substituents, which display diverse pharmacological activities19. In course of a systematic exploration for new bioactive secondary metabolites with novel structure20,21,22, three unprecedented structures (1–3, Fig. 1) were isolated from the aerial parts of H. scabrum. Although there are many examples of homo-adamantane PPAPs with a tricyclo[4.3.1.15,7]-undecane skeleton12,23,24, compound 1 illustrates the first example of an esterified PPAP that features an unrivaled tricyclo-[4.3.1.11,4]-undecane skeleton. Compound 2 is a reasonably simple monocyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol (MPAP) with a unique cycloheptane ring decorated with prenyl substituents, and compound 3 has an unusual 5,5-spiroketal lactone core.

We here report on the structure elucidation of these compounds, including their absolute configuration, proposed biosynthetic pathways, and on the evaluation of their biological activity.

Results and discussion

Compound 1 was obtained as yellow gum {[α] 25D + 17.2 (c = 1.0, CH3OH)}. Its molecular formula was deduced as C33H42O6 by HR-ESIMS at m/z 535.3067 [M + H]+ (calcd 535.3054), indicating 13 degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 (Table 1) revealed signals of eight methyl singlets (δH 1.00, 1.05, 1.37, 1.46, 1.50 , 1.54, 1.58, 1.65), two olefinic protons (δH 5.26, 1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz; 4.91, 1H, m), and a phenyl group (δH 7.87, 2H, dd, J = 8.4, 1.2 Hz; 7.51, 1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz; 7.36, 2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz). Analysis of the 13C NMR (Table 1) and HSQC spectra of 1 exhibited 33 carbon signals comprising three carbonyl groups [δC 203.3, 201.4, 200.9], a benzoate group [δC 165.6, 134.0, 129.9 × 2, 128.7 × 2, 127.9], eight methyls, four methylenes, four methines, and six quaternary carbons. The aforementioned data indicated some structural aspects of 7-epi-clusianone (4, Fig. 5), a BPAP with a normal bicyclo[3.3.1]-nonane core25, that was also isolated in this study26. The main spectral differences between 1 and 4 were due to the significant variations in the NMR data of the perenyl group at C-1, replacement of a benzylic ketone at δC 197.7 with a benzylic ester at δC 165.6, and replacement of an enolic carbon at δC 196.5 with a ketonic one at δC 200.9. Detailed analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra indicated that a [CHC(CH3)2OH] group in 1 replaced the isobutenyl moiety at C10 in 4. This deduction was corroborated by the key HMBC correlations from H3-13 (δH 1.37) and H3-14 (δH 1.46) to C-12 (δC 75.0) and C-11 (δC 45.4), coupled with the 1H-1H COSY correlation between H-11 (δH 2.11) and H2-10 (δH 1.92 and 1.98), as shown in Fig. 2. Additionally, HMBC correlations from H-11 to C-3 (δC 89.5), C-4 (δC 200.9), C-2 (δC 201.4), and from H2-10 to C-3 and C-8 (δC 46.3), demonstrated the foundation of a five-membered ring by the connection of C-11 to C-3. In the HMBC spectrum, correlations from aromatic protons (δH 7.87) to the resonance of a carbonyl group at (δC 165.6), supported by the upfield shift of C-3 resonance (δC 89.5) compared to it at 4 (δC 115.9), suggested the displacement of a benzoate ester at C-3 instead of the phenyl ketone. Moreover, HMBC correlations from H2-22 and H2-6 to the carbonyl resonances at δC 200.9 and δC 203.3 confirmed the position of the two other ketone groups at C-4 and C-9. The remaining parts of the molecule were similar to those of 4. Thus, the gross structure of 1 was established as depicted in Fig. 1.

The NOESY spectrum (Fig. 3) demonstrated correlations from H-7 to H-6β and H3-33, and from H3-33 to H-10β and certified their cofacial orientation. Also, diagnostic cross-peaks from H-27a to H3-32 and H-6α, from H3-32 to H-10α, and from H-10α to H-11, revealed their equal orientation. The absolute stereochemistry was specified by comparing the calculated ECD spectra with the experimental one. The experimental data showed two positive Cotton effects (CE) at 280 and 205 nm, along with negative CE at 220 nm (Fig. 4). The calculated ECD spectrum for 1R, 3S, 5S, 7R, 11R showed a good compatibility with the experimental data.

The hypothetical biogenetic pathway of 1 is proposed in Fig. 5. 7-epi-clusianone (4), an endo-bicyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol (endo-BPAP) is assumed to be a precursor. The structural novelty of 1 involves ring closure of the enone moiety upon the epoxy function of the prenyl chain at C-1, to form a rigid caged tetracyclo-[4.3.1.11,4]-undecane skeleton. Furthermore, a Baeyer–Villiger oxidation is required to create 1 as the first esterified PPAP in nature.

Compound 2 was obtained as a white powder {[α] 25D + 30.5 (c = 1.0, CHCl3)}. Its molecular formula was distinguished as C24H28O6 by HR-ESIMS at m/z 413.1941 [M + H]+ (calcd 413.1959), proposing 11 degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 (Table 1) displayed signals of a mono-substituted phenyl group (δH 7.77, 2H, dd, J = 8.3, 1.2 Hz; 7.46, 1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz; 7.35, 2H, t, J = 7.7 Hz), five methyl singlets (δH 1.05, 1.12, 1.20, 1.39, 1.77), two diastereotopic methylenes [(δH 1.83, 1H, m; 2.13, 1H, ddd, J = 13.7, 6.9, 1.7 Hz); and (δH 1.90, 1H, ddd, J = 12.9, 11.0, 9.2 Hz; 2.52, 1H, ddd, J = 12.9, 9.0, 1.2 Hz)], and three methines including one oxygenated (δH 2.43, 1H, dd, J = 12.1, 6.9 Hz; 3.61, 1H, m; 4.25, 1H, dd, J = 9.2, 1.2 Hz). The 13C spectrum of 2 (Table 1) showed 24 carbon signals including five methyls, two methylenes, eight methines (five aromatics) and nine quaternary carbons (one aromatic). Accordingly, 27 protons could be numerated, while the unaccounted one could be due to the presence of an OH substituent in the structure. Deshielded 13C NMR resonances at δC 193.7 (C-2), 113.5 (C-3), and 179.0 (C-4) proposed the attendance of an α,β-unsaturated ketone moiety comprising a tetrasubstituted olefinic group and an oxygen substituent at the β-position. The resonances at δC 174.1 (C-8) and 193.5 (C-18) were indicative of two other carbonyl groups. Three carbon signals at δC 72.6 (C-15), 83.6 (C-9), and 90.1 (C-14) indicated the entity of oxygenbearing sp3 carbons. Considering the number of sp2 or sp carbon resonances and 11 degrees of hydrogen deficiency, a tricyclic core structure for compound 2 was clearly deduced that possesses a seven-membered carbocyclic ring, a cyclic ether and a lactone moiety. By interpreting COSY correlations (Fig. 2), it was thinkable to create a long proton connection from H-7 to H-14 through H2-6, H-5, and H2-13. The HMBC spectrum showed correlations from H-5 to C-3, C-4, C-6, and C-7, and from H-7 to C-1 and C-2, proving the seven-member carbocyclic ring as the core of the structure. HMBC correlations from H-14 to C-4, C-15, C-16, and C-17 resulted in the construction of the ether ring with a substituted 2-propanol moiety. HMBC cross-peaks from H3-10 and H3-11 to C-9 and C-7, and from H-7 to C-9, corroborated the nature of the lactone moiety. The fifth methyl group was placed at C-1 pursuant to the HMBC cross-peaks of H3-12 with C-1, C-2, C-7, and C-8. In the HMBC spectrum, correlations from aromatic protons (δH 7.77) to the resonance of a carbonyl group at (δC 193.5) supported the presence of the benzoyl moiety at C-3. However, no direct HMBC correlations to C-3 were observed.

The relative stereochemistry of 2 was resolved by inspecting the NOESY spectrum (Fig. 3). In the NOESY spectrum, H3-12 showed NOE correlations with H-7 and H-5, indicating their α-orientations. The fact that no NOE correlation peaks were found between H-5 and H-14, and instead, a cross-peak was detected between H-5 and H3-16, indicated the β orientation of H-14. Conclusive evidence for the postulated structure of 2 was obtained from a single-crystal X-ray structure analysis, which precisely confirmed the absolute configuration as (1S, 5S, 7S, 14R) (Fig. 6).

Many bi- and tricyclic PPAPs have been reported to occur in nature, however compound 2 is the first monocyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol (MPAP) with a cycloheptane ring decorated with prenyl substituents.

Biosynthetically, compound 2 is presumably derived from a common phloroglucinol core (Fig. 7) via methylation at C-1 and diprenylation at C-5, followed by the C-alkylation of the epoxide intermediate to form the C1–C7 bond. This intermediate contains a bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2,4,8-trione core that was found in a smaller group of PPAPs27. A Baeyer–Villiger oxidation, followed by a ring opening through the nucleophilic attachment of NADPH, would then form the cycloheptane key ring. Finally, successive formation of the hydrofuran and lactone rings via etherification and lactonization of the side chains would lead to compound 2.

Compound 3, colorless oil {[α] 25D + 9.1 (c = 1.0, CH3OH)}, showed an accurate HR-ESIMS ion at m/z 293.1366 [M + Na]+ (calcd 293.1365), revealing the molecular formula as C14H22O5 and four indices of hydrogen deficiency. 14 carbon resonances can be observed from the 13C NMRspectrum of 3 (Table 2), corresponding to five methyls, two methylenes, two methines and five quaternary carbons. Accordingly, twenty-one of the hydrogens were carbon-bonded, so the remaining one could belong to a hydroxyl group. The 13C NMR spectrum displayed signals suggestive of a carbonyl carbon (δC 172.7) and four oxygenbearing carbons [δC 76.5 (CH), 83.6 (C), 84.7 (C) and 85.8 (C)]. The lack of any other olefinic carbon signals indicated that 3 contains three heterocycle rings, to fulfill its degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR(Table 2) spectrum of 3 recorded in C5D5N revealed the distinguished resonances of five methyl singlets (δH 1.22, 1.35, 1.40, 1.55, 1.83), two diastereotopic methylenes [(δH 2.30, 1H, m; 2.38, 1H, dd, J = 9.5, 2.1 Hz); and (δH 2.48, 1H, dd, J = 14.2, 3.9 Hz; 2.54, 1H, dd, J = 14.2, 5.8 Hz)], and two methines including one oxygenated (δH 4.37, dd, J = 5.7, 3.9 Hz) and one nonoxygenated (δH 2.32, m). The partial structure of 3 was established from a combination of HSQC, 1H–1H COSY, and HMBC experiments in C5D5N and CDCl3. HMBC correlations from H3-11 and H3-12 to C-7 and C-6, and from H3-10 to C-6, C-8, and C-9, corroborated the constitution of the lactone ring. HMBC cross-peaks of H-6 and H2-5 with C-4 confirmed the attendance of a five-membered heterocyclic ring B. HMBC data (correlations from H3-13 and H3-14 to C-1 and C-2, and from H-2 to C-3 and C-4) revealed the connectivity between C1–C2–C3–C4 as ring A (Fig. 8). Finally, correlations of H2-3 with C-5, and of H2-5 with C-3, implied that the C-4 tertiary carbon was a bridgehead between C-3 and C-5 as a spiroketal.

The NOESY spectrum (Fig. 8) represented correlations between H-6, H3-10 and H3-11, as well as between H3-12 and H-5β, which emphasized the connection of rings B and C. Similarly, cross-peaks between H3-10 and H-3α, between H-5α and H-3β, between H-3α and H-2, as well as between H-3β and H3-13, were noticed and confirmed the linkage of rings A and B. The ECD spectrum of compound 3 showed a negative Cotton effect (CE) at 275 nm and a positive CE at 250 nm. Comparing the experimental ECD curve of 3 with calculated one resulted in deciphering the absolute stereochemistry of 3 as 2S, 4S, 6S, 8S (Fig. 9).

Isolation of 3 with intriguing 5,5-spiroketal lactone structure represents the first discovery from nature. From a biogenetic viewpoint, acetate and mevalonate pathways might be involved in the biosynthesis of this new scaffold. Although two isoprene C5 units appear to be involved in this process, it does not seem to fit the regular alkylation mechanism (Fig. 10).

Compounds 1–3 were examined for their in vitro antiprotozoal activity against the protozoan parasites Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and Plasmodium falciparum. Cytotoxicity was investigated in rat skeletal myoblast L6 cells and the selectivity indices (SI) for these compounds were calculated (Table 3).

Four known polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols hyperibone A-C15a and 7-epi-clusianone25, and two aromadendrane sesquiterpenoids lochmolin F28 and aromadendrane-4β,10β-diol29 were also isolated and identified in this study. Hyperibone A-C have been previously reported from the aerial parts of the plant, but the remainings were isolated for the first time from this species.

Methods

General experimental procedures

Optical rotation, UV and ECD spectra, and HR-ESIMS data were recorded as reported previously by us30. NMR experiments were measured on Bruker Avance III 500 and Bruker Avance II 600 spectrometers, using standard Bruker pulse sequences. HPLC separations were performed on a Knauer HPLC system according to our previous report30. Column chromatography (CC) was carried out on silica gel (70–230 mesh, Merck). TLC pre-coated silica gel F254 plates (Merck)) were used to detect and merge fractions; visualizing under UV light or by heating the plates after spraying with anisaldehyde-sulfuric acid reagent.

Plant material

The aerial parts of H. Scabrum were gathered in the north of Iran in Yush village from Baladeh District, in June 2015. A voucher specimen was authenticated by Dr. Ali Sonboli and was deposited in the Herbarium of the Medicinal Plants and Drugs Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University (MPH-2510).

Extraction and isolation

After drying and powdering, the-aerial parts of H. scabrum (5.0 kg) were extracted (3 × 20 L, 24 h) with n-hexane, and the mixed extracts were condensed under vaccum to give a gummy residue (150 g). The dried extract was fractionated by open column chromatography on silica gel (1.0 kg, 5 × 100 cm, 70–230 mesh) eluted with a gradient of n-hexane–EtOAc (100:0 to 0:100), and then increasing amounts of MeOH (up to 50%). On the bases of TLC analysis, eight combined fractions (Fr.1-Fr.8) were obtained. From Fr.1 [eluted with n-hexane–EtOAc (95:5)] a yellow crude solid was obtained, which was triturated with MeOH to give 7-epi-clusianone (4) as white powder (100 mg). Fr.2 (1.0 g) was further purified on silica gel column chromatography (200 g, 2 × 60 cm) and eluted with n-hexane-CH2Cl2-(CH3)2CO (58:40:2) to get four subfractions (Fr.2.1-Fr.2.4). Fr.2.2 (70 mg) was subjected to silica gel column (70 g, 1 × 50 cm) eluted with n-hexane-(CH3)2CO (90:10) to afford compound 1 (7.0 mg). Fr.2.3 (150 mg) was submitted to a silica gel column (140 g, 1.5 × 70 cm), eluted with n-hexane-(CH3)2CO (80:20) to obtain two subfractions (Fr.2.3a-Fr.2.3b). Repeated purification of Fr.2.3a (80 mg) by silica gel CC [100 g, 1 × 70 cm, eluted with CH2Cl2-(CH3)2CO (97:3)], afforded hyperibone A (2.5 mg), hyperibone B (1.5 mg) and hyperibone C (14 mg). Fr.4 (1.9 g) was further separated via silica gel column chromatography (300 g, 4 × 60 cm) using CH2Cl2-(CH3)2CO (95:5) as eluent to produce five subfractions (Fr.4.1-Fr.4.5). Fr.4.1 (170 mg) was further chromatographed on silica gel (150 g, 1.5 × 80 cm) using CH2Cl2-1-propanol-MeOH (95:4:1) as mobile phase to yield lochmolin F (5.7 mg) and aromadendrane-4β,10β-diol (2 mg). Fr.4.3 (100 mg) was also separated on silica gel (120 g, 1.5 × 50 cm) and eluted with n-hexane-(CH3)2CO (75:25) to obtain compound 3 (3.9 mg). Fr 7 (2.1 g) was subsequently chromatographed on a silica gel CC (300 g, 4 × 60 cm) eluted with n-hexane-(CH3)2CO (65:35) and followed by increasing concentrations of 1-propanol (2%) to give four subfractions (Fr.7.1–Fr.7.4). Fr.7.3 (400 mg) was applied to a silica gel column (100 g, 2.0 × 80 cm) and eluted with n-hexane-CHCl3-MeOH (47:47:6) to give six subfractions (Fr.7.3.1–Fr.7.3.6). Fr.7.3.6 (40 mg) was separated by preparative reversed-phase HPLC using the mobile phase of MeCN-H2O (55:45, v/v) to yield compound 2 (1.6 mg).

-

Compound 1 Yellow gum, [α] 25D + 17.2 (c = 1.0, CH3OH); HR-ESIMS [M + H]+ m/z 535.3067 (calcd for C33H43O6, 535.3054); 1H and 13C NMR data in Table 1.

-

Compound 2 White powder, [α] 25D + 30.5 (c = 1.0, CHCl3); HR-ESIMS [M + H]+ m/z 413.1941 (calcd for C24H29O6, 413.1959); 1H and 13C NMR data in Table 1.

-

Compound 3 Colorless oil, [α] 25D + 9.1 (c = 1.0, CH3OH); HR-ESIMS [M + Na]+ m/z 293.1366 (calcd for C14H22O5Na, 293.1365); 1H and 13C NMR data in Table 2.

X-ray crystallographic analysis of 2

C24H28O6, colorless prism, 0.20 × 0.08 × 0.05 mm, space group P212121, orthogonal, a = 6.8847(4) Å, b = 15.1910(16) Å, c = 20.6691(14) Å, V = 2161.7(3) Å3, Z = 4, ρcalcd = 1.267 g·cm‒3, T = 173 K, Cu radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å), θ range 3.6°‒62.1°, 5988 reflections collected, 3323 independent, Rint = 0.0708, 308 parameters, wR2 = 0.1110 (all data), R1 = 0.0512 [I > 2σ(I)], absolute structure parameter 0.0(2). The crystal data of compound 2 was placed in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC 1992711).

ECD calculations of 1 and 3

Conformational analysis of compounds 1 and 3 was carried out on MacroModel 9.1 software by applying OPLS-2005 force field in H2O (Schrödinger LLC) with the Gaussian 09 program package31, and ECD curves were obtained using SpecDis version1.6432.

In vitro antiprotozoal assay

The in vitro inhibitory activities of compounds 1–3 were evaluated against the protozoan parasites T. b. rhodesiense (STIB900) trypomastigotes and P. falciparum (NF54) LEF stage and cytotoxicity in L6 cells (rat skeletal myoblasts) by adopting the same procedures as the reported previously33,34.

References

Tanaka, N. et al. Biyouyanagin A, an anti-HIV agent from Hypericum chinense L. var. salicifolium. Org. Lett. 7, 2997–2999 (2005).

Henry, G. E. et al. Acylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum prolificum. J. Nat. Prod. 69, 1645–1648 (2006).

Nürk, N. M. & Blattner, F. R. Cladistic analysis of morphological characters in Hypericum (Hypericaceae). Taxon 59, 1495–1507 (2010).

Zhang, J.-J. et al. Hypercohones D-G, new polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol type natrural products from Hypericum cohaerens. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 4, 73–79 (2014).

Tanaka, N., Abe, Sh., Hasegawa, K., Shiro, M. & Kobayashi, J. Biyoulactones A-C, new pentacyclic meroterpenoids from Hypericum chinense. Org. Lett. 13, 5488–5491 (2011).

Fobofou, S. A. T., Franke, K., Porzel, A., Brandt, W. & Wessjohann, L. A. Tricyclicacylphloroglucinols from Hypericum lanceolatumandregioselective synthesis of selancins A and B. J. Nat. Prod. 79, 743–753 (2016).

Cardona, L., Pedro, J. R., Serrano, A., Munoz, M. C. & Solans, X. Spiroterpenoids from Hypericum reflexum. Phytochemistry 33, 1185–1187 (1993).

Tanaka, N. et al. Acylphloroglucinol, biyouyanagiol, biyouyanagin B, and related spiro lactones from Hypericum chinense. J. Nat. Prod. 72, 1447–1452 (2009).

Zhu, H. et al. Hyperascyrones A-H, polyprenylated spirocyclic acylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum ascyron Linn. Phytochemistry 115, 222–230 (2015).

Hu, L. et al. (±)-Japonones A and B, two pairs of new enantiomers with anti-KSHV activities from Hypericum japonicum. Sci. Rep. 6, 27588 (2016).

Schiavone, B. I. et al. Biological evaluation of hyperforin and hydrogenated analogue on bacterial growth and biofilm production. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 1819–1823 (2013).

Li, D. et al. Two new adamantyl-like polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols from Hypericum attenuatum choisy. Tetrahedron Lett. 56, 1953–1955 (2015).

Tanaka, N. et al. Xanthones from Hypericum chinense and their cytotoxicity evaluation. Phytochemistry 70, 1456–1461 (2009).

Ghasemi Pirbalouti, A., Jahanbazi, P., Enteshari, S. H., Malekpoor, F. & Hamedi, B. Belgrade. Arch. Biol. Sci. 62, 633–642 (2010).

Matsuhisa, M. et al. Benzoylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum scabrum. J. Nat. Prod. 65, 290–294 (2002).

Matsuhisa, M. et al. Prenylated benzophenones and xanthones from Hypericum scabrum. J. Nat. Prod. 65, 290–294 (2004).

Gao, W. et al. Polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols congeners from Hypericum scabrum. J. Nat. Prod. 79, 1538–1547 (2016).

Gao, W. et al. Polyisoprenylated benzoylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum scabrum. Fitoterapia 115, 128–134 (2016).

Ciochina, R. & Grossman, R. B. Polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols. Chem. Rev. 106, 3963–3986 (2006).

Moridi Farimani, M. et al. Hydrangenone, a new isoprenoid with an unprecedented skeleton from Salvia hydrangea. Org. Lett. 14, 166–169 (2012).

Moridi Farimani, M. et al. Phytochemical study of Salvia lerrifoliaroots: rearranged abietane diterpenoids with antiprotozoal activity. J. Nat. Prod. 81, 1384–1390 (2018).

Tabefam, M. et al. Antiprotozoal isoprenoids from Salvia hydrangea. J. Nat. Prod. 81, 2682–2691 (2018).

Tian, W.-J. et al. Dioxasampsones A and B, two polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols with unusual epoxy-ring-fusedskeleton from Hypericum sampsonii. Org. Lett. 16, 6346–6349 (2014).

Yang, X.-W. et al. Polyprenylated acylphloroglucinolscongeners possessing diverse structures from Hypericum henryi. J. Nat. Prod. 78, 885–895 (2015).

Piccinelli, A. L. et al. Structural revision of clusianone and 7-epi-clusianone and anti-HIV activity of polyisoprenylated benzophenones. Tetrahedron 61, 8206–8211 (2005).

Taylor, W. F. et al. 7-epi-Clusianone, a multi-targeting natural product with potential chemotherapeutic, immune-modulating, and anti-angiogenic properties. Molecules 24, 4415 (2019).

George, J., Hesse, M. D., Baldwin, J. E. & Adlington, R. M. Biomimetic syntheses of polycylic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol natural products isolated from Hypericum papuanum. Org. Lett. 15, 3532–3535 (2010).

Tseng, Y.-J. et al. Lochmolins A-G, new sesquiterpenoids from the soft coral Sinularia lochmodes. Mar. Drugs 10, 1572–1581 (2012).

Huong, N.-T. et al. Eudesmane and aromadendrane sesquiterpenoids from the Vietnamese soft coral Sinularia erecta. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 1798–1802 (2018).

Tabatabaei, S. M. et al. Antiprotozoal germacranolide sesquiterpene lactones from Tanacetum sonbolii. Planta Med. 85, 424–430 (2019).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D. 01 (Gaussian. Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2009).

Bruhn, T., Schaumlöffel, A., Hemberger, Y. & Bringmann, G. SpecDis: Quantifying the comparison of calculated and experimental electronic circular dichroism spectra. Chirality 25, 243–249 (2013).

Orhan, I., Şener, B., Kaiser, M., Brun, R. & Tasdemir, D. Inhibitory activity of marine sponge-derived natural products against parasitic protozoa. Mar. Drugs 8, 47–58 (2010).

Zimmermann, S., Kaiser, M., Brun, R., Hamburger, M. & Adams, M. The first plant natural product with in vivo activity against Trypanosoma brucei. Planta Med. 78, 553–556 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Financial supports by the Golestan and Shahid Beheshti Universities Research Councils are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.F. designed and coordinated the project. S.S. performed the extraction, isolation and structural identification of the compounds. M.A., M.T. and O.D. helped with the experimental procedures. T.G. conducted the X-ray crystal structure analysis. S.N.E. calculated the ECD data. M.K. carried out the biological assays. M.H. and H.S. provided the instrumental facilities and edited and polished the manuscript. S.S., M.A. and M.M.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soroury, S., Alilou, M., Gelbrich, T. et al. Unusual derivatives from Hypericum scabrum. Sci Rep 10, 22181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79305-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79305-y