Abstract

Miniaturized integrated optical devices with low power consumption have long been considered hot candidates for plasmonic applications. While 2D materials such as graphene have been proposed for this purpose, they suffer from large propagation loss and low controllability at room temperature. Here, a silicene-based optical MOSFET with excellent performance is designed to achieve integrated circuit optical technology. The designed device is comprised of a silicene optical waveguide whose switching operation is performed by a gate and has a structure similar to an enhancement MOSFET with a formed channel. Unlike graphene, the surface conductivity of silicene can be controlled by both chemical potential and an electric field perpendicular to its surface. This unique feature of silicene is used to design and simulate an optical-MOSFET with transverse electric polarization at 300 K. The salient characteristics of the optical device include its nanoscale dimensions, ultra-low insertion loss of 0.13 dB, infinite extinction ratio, and quality factor of 688, proposing it as a promising tool for optical integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical telecommunications employing semiconductor lasers as the light sources, and optical fibers as the transmission media are the only current solution for managing and massive growth of telecommunication and data traffic. A fiber optic can provide a bandwidth of 25 THz, and a cable comprising ~ 1,000 optical fibers is capable of carrying 6 billion video calls simultaneously. New services such as high-definition television and network computing have been introduced, increasing the demand for high bandwidth networks. The potential bandwidth of these optical fibers can be fully realized by developing other components of the optical network system, (e.g., detectors, multiplexers, buffers, and switches), thereby allowing for a match of the transmission rate and bandwidth. In general, optical switches are related to the routing of message information in response to regulatory control signals. The message information can be in large blocks of multiple traffic in the optical core network or be in a large number of lower-bit channels for delivery to users in the optical network. However, the use of an optical switch may not only be limited to communication networks but may also include the communication cores of a large multiprocessor computer with a data rate exceeding 100 Gbps. By experimenting with new designs that use quantum phenomena for secure communication and computing, new architectures would be needed for switches without interrupting the basic information of quantum packets1.

Based on their structure and operation, optical switches have different types, the most important of which are electro-optical2, thermal-optical3, magnetic-optical4, MEMS-based5, SOA-based6, and photonic crystals –based7 switches. In addition to the aforementioned technologies, it is possible to realize a new type of optical switch in optoelectronics8 when it comes to the advent of 2D materials such as graphene with the capability of controlling the density of highly mobile electrons on the surface.

The discovery of graphene has greatly motivated the research on graphene-like 2D materials, including hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)9, silicene10, germanene (i.e., hexagonal networks of silicon and germanium)11, stanene12, phosphorene13, and chemical constituents of transition metals with the typical formula of MX214. Among these materials, silicene has received more attention due to its compatibility with current technology, as well as its interesting electrical and optical properties. However, silicene does not have a layered bulky counterpart such as graphite, so the synthesis of this 2D material requires a bottom-up method (e.g., epitaxial growth on a substrate)15.

The theoretical study of silicene goes back to an article by Takeda and Shiraishi on the hexagonal rings of silicon and germanium, referred to as their carbon counterpart16. One of the most important 2D structures is silicene, in which the presence of massless Dirac fermions has been predicted. Moreover, silicene has shown a spin-quantum effect17. Nevertheless, the major challenge facing silicene is that it cannot remain stable in air, and reacts easily with oxygen atoms, thereby producing Si–O18,19,20. So far, some approaches such as silicene hydrogenation and encapsulation have been proposed to solve this problem21. In the silicene hydrogenation approach, nitrogen atoms are bonded to silicon atoms, thus preventing silicene from reacting with oxygen.

On the other hand, silicene can be encapsulated between Al2O319,20 and22, h-BN23 and24, and graphene25. The authors in20 have developed a method that preserves silicene during the fabrication and transfer processes of the device. In this case, using Al2O3 during the fabrication process, silicene was encapsulated to prevent its reaction with air. This method can also be applied to other materials (germanium, phosphorus, etc.).

Generally, in addition to Al2O3, h-BN is also used between silicene and oxide layers to maintain the structure, high carrier mobility26, and optical properties of silicene27. The h-BN layer as a buffer is important in the fabrication of devices based on intrinsic silicene24. The presence of an h-BN layer on silicene prevents the formation of covalent bonds. In addition, both silicene and h-BN have been observed to retain their structure and remain intact when they are in contact with each other. This stands true when these layers are exposed to a vertical electric field. By inserting an h-BN layer into the silicene-based device, one can maintain structural symmetry. Since the interactions between silicene and h-BN are of the van der Waals type, it is possible to use materials such as silicon carbide (SiC) and graphene to act as h-BN in silicene-based devices28–30.

Apart from the studies performed on silicene encapsulation, other investigations into the optical and electrical properties of silicene nanoribbons and silicene nanotubes have been reported in the literature31,32. Research on the types of silicene buckling (i.e., low and high buckling) and its properties has also been performed33. Due to the challenges mentioned above, silicene has been proposed as a preferred material in recent decades, providing integration with silicon-based technology. This integration is one of primary advantages of silicene as a material for future electronic devices with the availability of a bulk infrastructure for the silicon technology. Silicene has been utilized to design several electronic and optical devices, ranging from metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) to optical detectors for use in molecular sensors.

Various configurations of silicene-based FETs have been reported, the most important of which are dual-gated silicene FET, silicene-based FET with alkaline absorbers, silicene nanoribbon-based FET, Z-shaped silicene nanoribbon FET, silicene nanotube-based FET, and Li-Cl co-decorated silicene FET.

Ni et al. investigated a silicene FET with a dual-gate configuration in which the silicene layer sandwiched between h-BN buffer and SiO2 dielectric layers24, allowing for the control of both the doping level and the electric field perpendicular to the silicene surface. The ON/OFF ratio of the resulting device current was obtained to be about 4.3 at room temperature, which is a very low value due to the direct effect of the short channel of the device. In Ref.26, the authors designed a FET consisting of a central region and two electrodes made of silicene using the adsorption of Na atoms on the silicene surface. The dielectric layer was made of SiO2, and an h-BN layer was used in the structure to prevent the interaction between silicene and SiO2. In this case, the ON/OFF ratio reached about 4 × 108. Alternatively, Selimian et al. designed a FET using silicene nanorods34, outperforming FETs fabricated based on graphene nanorods. Li et al. also reported a FET based on Z-shaped silicene nanoribbons, having an ON/OFF ratio of about 10635.

In another investigation, silicene nanotubes were employed to fabricate a FET with an ON/OFF ratio of about 107, which is higher than that of graphene counterpart36. In Ref.23, researchers have proposed a new method for designing a high-performance FET channel by decorating silicene with Li and Cl. The electrodes and channel of the device were made of silicene and Li-Cl co-decorated silicene, respectively, giving rise to an ON/OFF ratio of 4.66 × 104.

By using an ion-sensitive field-effect transistor (ISFET) structure with silicene layers and electrolyte, Sazzadur Rahman et al. have designed a sensor with the capability of label-free detection of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) for disease-related gene expression37. Also, Kharadi et al. reported an optical detector using silicene-MoS2 heterojunction with high efficiency38. This was the first time that the silicene-MoS2 heterojunction had been investigated as a high-performance device for optical detector applications. Elsewhere, two optical switches have recently been proposed based on silicene. The first one was a plasmonic electro-optical switch based on a silicene waveguide encapsulated between layers of Al2O339, providing a better performance compared to its graphene counterpart. The second switch was designed based on metamaterials, utilizing graphene-silicene-graphene (G-S-G) structure to control the switching of the transmitted light40.

Silicene has unique properties compared to graphene41, the most important advantage of which is the tunability of the band gap with an external field perpendicular to the surface. However, no attention has been paid to the design of a silicene-based optical MOSFET (OMOSFET), according to the best of our knowledge. In this essay, a plasmonic switch is designed and employed as an OMOSFET using silicene that emits surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) in transverse electric (TE) mode. Electromagnetic waves propagating along the surface between a metal (or semiconductor) and a dielectric are generally in the infrared range42. Metals such as gold and silver are commonly used to emit surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs)43. In recent years, graphene has been used to emit SPPs44, outperforming gold and silver in terms of adjustability and confinement limit with fewer losses.

While conventional MOSFETs use a gate to control and transmit the electrical charge, our proposed OMOSFET uses a gate to control (turn on or off) an optical signal with TE polarization. Therefore, the proposed device can be a suitable candidate for designing optical processors that use optical signals instead of electrical signals for data processing, thereby avoiding overheating problems and having the capability to work at THz speeds. The structure of the article is outlined as follows: In section "Physical structure of the proposed device", we describe the physical structure and performance of the proposed device. In sections "Device modeling"‒“Switching performance”, we discuss the mathematical relations of the problem and present the results of the numerical simulation. In section "Fabrication process", we analyze the evaluation of the switching performance of the proposed device, and finally, in the last section we have presented the method of fabrication the proposed device.

Physical structure of the proposed device

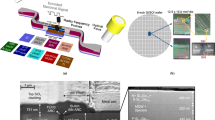

Figure 1 shows the design of the proposed OMOSFET. A 3D view of the optical switch is depicted in Fig. 1(a). In this switch, a silicene waveguide is encapsulated between two h-BN layers. The bottom h-BN layer has a thickness of 100 nm, acting as both the silicene substrate and buffer to prevent the silicon atoms from reacting with SiO2. The 5 nm-thick top BN layer is employed as both the protective layer for the silicene monolayer (thus preventing silicon atoms from reacting with air) and the dielectric gate. Figure 1(b) shows a cross-section of the proposed switch. In this figure, the operation of the optical switch is presented. The structure of this switch is similar to an enhancement-MOSFET. By applying a suitable voltage to the gate, a constant electric field perpendicular to the silicene surface is created, providing the necessary conditions for the transmission of TE waves. When the gate voltage is cut off, the TE wave can no longer be transmitted due to the zero electric field.

Device modeling

The proposed OMOSFET operates in the TE mode. The electric vector (E) in the TE mode is always perpendicular to the propagation direction. In general, the TE mode types are defined as TEm,n, where m and n are the numbers of half-wave patterns across the width and height of the waveguide, respectively. The numbers m and n can always have integer values from zero to infinity, indicating the wave modes inside a waveguide45. The electric field and magnetic field components of TE waves are defined as follows46:

and

where γi is the decay constant and given by: \(\gamma_{i} = q_{ \circ } \sqrt {q^{2} - \varepsilon_{i} \mu_{i} }\), in which q is the propagation constant and q0 is the wave vector in the free space (\(q_{ \circ } = \omega /c\)). Since the silicene waveguide in the proposed device is surrounded by the h-BN layer, one can obtain Eq. (3) by applying boundary conditions (\(\vec{E}_{y1} = \vec{E}_{y2} ,{ }\vec{H}_{x1} - \vec{H}_{x2} = \sigma_{s} \vec{E}_{y} ,{ }\vec{B}_{1} = \vec{B}_{2}\)) and solving Maxwell's equations as follows:

The dispersion relation for the TE wave is expressed below:

Since \(\mu_{hBN}^{1} = \mu_{hBN}^{2} = 1\) and \(\gamma_{hBN}^{1} = \gamma_{hBN}^{2} = \gamma\), Eq. (4) is simplified as follows:

where \(\sigma_{s}\) is the surface conductivity of silicene and ω is the angular frequency. The above equation is satisfied when the imaginary part of \(\sigma_{s}\) becomes negative, thereby initially requiring the calculation of \(\sigma_{s} = \sigma_{{{\text{intra}}}} + \sigma_{{{\text{inter}}}}\). The intra-band and inter-band conductivity contributions are obtained from the following relations47:

where \(\varsigma = + 1( - 1)\) and \(\eta = + 1( - 1)\) are the electron spin up (spin down) index, and k(k') valley electrons index. \(E_{ \bot }\) is the electric field perpendicular to the silicene surface, and \({\upmu }_{C}\) is the chemical potential (Fermi energy) of silicene. Furthermore, e, k, T, \(\epsilon\) and ћ denote the electron charge, Boltzmann's constant, temperature, electrical energy, and Planck's constant, respectively. \(\Gamma = 10^{ - 5} eV\) is the phenomenological dispersion rate and \(\theta [\omega ,\xi ,\eta ]\) is the Heaviside function. \(\Delta [\varsigma ,\eta ,\,E_{ \bot } ]\) represents the band gap amplitude of silicene, being dependent on \(\varsigma\), \(\eta\), and \(E_{ \bot }\). d = 0.46 Å is the vertical distance between silicene sublattices, and \(\lambda_{SO} = 3.9\,\,meV\) represents the spin–orbit coupling strength of silicene.

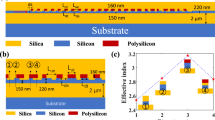

As can be inferred from the above relationships, the surface conductivity of silicene, unlike graphene, can be controlled by \(E_{ \bot }\), in addition to being controllable the chemical potential. In Ref.48, the comparison between emission regimes of TE waves of silicene and graphene has been investigated. Ukhtary et al. showed that by applying \(E_{ \bot }\), TE waves can be propagated in a larger frequency range for silicene. While the TE wave propagation range for graphene is only possible in a narrow frequency range of \(1.667E_{F} < \hbar \omega < 2E_{F}\)49, it can be increased for silicene by increasing \(E_{ \bot }\). Hence, an OMOSFET was designed in the present study using this feature of silicene. According to.the structure shown in Fig. 1, \(E_{ \bot } = E_{z}\) is created by the gate terminal to control \(\sigma_{s}\) and fulfill Eq. (5). As a result, \(E_{z}\) is considered to be the main variable. Figure 2 shows the changes in the real and imaginary parts of \(\sigma_{s}\) for \(E_{z} = 60 - 210mV/\)Å. These values were investigated for different frequencies in the range from 10 to 20 THz at the temperature of 300 K.

According to \(1/\gamma = 2/i\omega \sigma_{s} \mu_{0}\) for TE waves49, where \(1/\gamma\) is the optical confinement length and \(\mu_{0}\) is the vacuum permeability, better propagation of surface waves occurs at smaller values of \(1/\gamma\). As a result, larger values of the imaginary part of conductivity (\({\text{Im}} \,\sigma_{s}\)) provide smaller values of the confinement length. In addition, TE surface waves are not damped when \({\text{Re}} \,\sigma_{s} = 0\)46. Based on these key points, the best performance in the transmission of TE waves occurs when \({\text{Re}} \,\sigma_{s} = 0\), and \({\text{Im}} \,\sigma_{s}\) is a large negative number (> − 60 µS). Thus, the ranges marked by dotted lines in Fig. 2 are taken into account.

h-BN is a uniaxial hyperbolic material with a tensor dielectric function. The performance of h-BN is characterized by the two following dielectric functions: one along the symmetry axis of the crystal (\(\varepsilon_{z} (\omega )\)), and the other in the base plane (\(\varepsilon_{ \bot } (\omega )\)). These dielectric functions can be written in one formula as follows50:

where \(\omega_{To}\) and \(\omega_{Lo}\) are the transverse and longitudinal frequencies of optical phonons, respectively, and \(\Gamma_{m}\) is the phonon damping constant. Moreover, m = z and m = \(\bot\) refer to out-of-plane and in-plane modes, respectively. The values of mentioned parameters are depicted in Table 1. Herein, the dielectric constant of SiO2 was set to \(\varepsilon_{{SiO_{2} }} = 2.3\).

Numerical results

The numerical finite element method (FEM) was used to simulate the proposed device. In this case, silicene was modeled under a surface current density boundary condition of \(J_{s} = \sigma_{s} \vec{E}(x,y)\), where \(J_{s}\) is the surface current density and \(\vec{E}(x,y)\) represents the electric field components in x and y directions. Moreover, perfect-matched layer PML boundary conditions were used for the input and output ports, according to Fig. 3.

Here, we investigate TE01 (m = 0 and n = 1) and TE02 (m = 0 and n = 2) emissions of the proposed device, where one-half wave and two half waves are propagated at the width of the waveguide, respectively. Figure 4 shows the profile of the electric field (\({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m)) in the TE01 mode at the frequency of 10 THz for WS = 150 nm. In this regard, Fig. 4 (a) shows \({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m) in 3D space obtained using Ez = 96.3 mV/Å at 300 K. Figure 4(b and c) shows \({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m) at the output port and the fluctuations of the transmission wave along the longitudinal axis x–z, respectively. As well, Fig. 5 shows \({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m) in the TE02 mode using Ez = 96.3 mV/Å and WS = 300 nm at 300 K and frequency of 10 THz.

(a) 3D view of the electric field (\({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m)) in the TE01 mode at the frequency of 10 THz for WS = 150 nm. (b) Distribution of the electric field (\({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m)) in the output port (y–z plane). (c) Electric field fluctuations along the length of the device (z-x plane).

(a) 3D view of the electric field (\({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m)) in the TE02 mode at the frequency of 10 THz for WS = 300 nm. (b) Distribution of the electric field (\({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m)) in the output port (y–z plane). (c) Electric field fluctuations along the length of the device (z-x plane).

The transmission spectra calculated for frequencies between 10 and 20 THz using different values of Im(σs) and Re(σs) = 0 is depicted in Fig. 6. As can be seen, the performance of the proposed OMOSFET remains the same for different frequencies. Each transmission spectrum has two resonances, among which the larger amplitude resonance was selected for the performance of the proposed OMOSFET. The amplitude of the selected resonance in the different frequencies is about 0.97, which is a significant value.

Figure 7 shows \({\vec{\text{E}}}\)(x) (V/m) at input frequencies of 10 to 20 THz. As observed, the performance of the device remains the same for different frequencies in terms of Im σs proportional to the frequency. To achieve the maximum transmission, the negative values of Im σs must also increase in proportion to the increase in the frequency. In this way, the effective value of Im σs is obtained to be 66.4 µS at the frequency of 10 THz. By doubling the frequency to 20 THz, the Im σs value is also doubled (Im σs = 132.8 µS).

Table 2 summarizes Im σs, Ez, and VG values for the maximum TE wave transmission. The values of Ez and Im σs were extracted from the numerical results of Figs. 2 and 6. The VG values were obtained from the relationship between the electrostatic field and the voltage VG = Ez.d, in which d is the gate dielectric thickness (d = 5 nm).

Switching performance

In this section, the switching performance of the proposed device is examined. The insertion loss (IL), extinction rate (ER), and quality factor (Q) are among the most important switching parameters. IL represents the amount of power loss in the optical signal when transmitted to the output port, which is given by51:

where Po is the output power and PI is the input power. ER is defined as the ratio of output power in the ON state to the OFF state. Ideally, no signal should be transmitted when the switch is off. The ER value is calculated from Eq. (11) 51

where Plow is the low output power in ON mode, and Phigh is the high output power in OFF mode. On the other hand, Q is defined as follows52:

Herein, Fr is the resonance frequency and FWHM is the full width at half maximum. Figure 8 (a) and (b) shows ON mode with VG = 4.82 V and OFF mode with VG = 0 V at 10 THz. The larger transmission amplitude represents the ON state, whereas VG = 0 V is considered the OFF state (Fig. 8 c). As can be seen, the transmission amplitude of the input wave in the ON and OFF modes is about 0.97 and 0, respectively. According to the numerical results, the values of IL, ER, and Q for the proposed device are found to be 0.13 dB, \(\infty\), and 688, respectively.

Table 3 shows a comparison between ON/OFF ratios of conventional silicene-based MOSFETs and the proposed OMOSFET. As can be seen, the proposed OMOSFET ON/OFF ratio is considerably higher due to the zero output of the OFF mode.

Also, in Table 4, we compare the performance of the proposed OMOSFET as an optical switch with several examples of switches based on silicene and graphene. As can be seen from the results, the proposed device has very low losses and a high Q-factor due to the zero output of the OFF mode and its sharp response.

Fabrication process

The challenges existing in the manufacture and synthesis of stable silicene have hindered the experimental development of silicene-based devices. As mentioned in the introduction section, researchers in Ref.20 were able to propose a method based on silicene encapsulation with Al2O3, maintaining the stability of silicene in the manufacturing and transfer processes. In addition, the authors in Ref.55 investigated the following three methods of silicene synthesis: i) thermal evaporation of silicene on a suitable substrate; ii) surface detachment of silicene from a substrate; and iii) intercalation through a silicide network.

According to the method described in Ref.20 and the compatibility of silicene with h-BN encapsulation27, we present the method shown in Fig. 9 in order to fabricate the proposed OMOSFET. Initially, an Ag (111) layer is deposited on a mica substrate, followed by depositing a monolayer of silicene and h-BN to encapsulate the silicene. In the next step, the mica layer is detached and the remaining layers are flipped, and then they are attached to the substrate of the device. Afterwards, the Ag layer is etched using a potassium-based iodine solution without damaging the underlying silicene layer20, and then the top h-BN layer is deposited. In the last step, the gate electrode is deposited on the device using gold.

The proposed OMOSFET fabrication steps based on the method presented in Ref. 20.

Conclusion

A silicene-based OMOSFET with excellent switching characteristics has been introduced and simulated using the finite element method. The TE-polarized input light of this OMOSFET was controlled by the gate terminal embedded at the top of the structure. The switching characteristics of the proposed device are nanometer dimensions, ultra-low insertion losses of 0.13 dB, infinite extinction ratio, and a quality factor of 688. Due to these excellent characteristics, this device can be an excellent candidate for optical integration soon.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, Baojun, and Soo-Jin Chua, eds. Optical switches: Materials and design. Woodhead Publishing, (2010).

Cai, Ming et al. Graphene electro-optical switch modulator by adjusting propagation length based on hybrid plasmonic waveguide in infrared band. Sensors 20(10), 2864 (2020).

Tian, Shuang et al. Multi-band thermal optical switch based on nematic liquid crystal filled photonic crystal fiber.. J. Lightwave Technol. 39(10), 3297 (2021).

Huang, Zhilin, and Jun Shen. Fabrication and characterization of a latching magnetic optical switch. Passiv. Compon. Fiber-based Dev. Vol. 5623. SPIE, (2005).

Kumar, R. A review on RF micro-electro-mechanical-systems (MEMS) switch for radio frequency applications. Microsyst. Technol. 27(7), 2525–2542 (2021).

Saha, Subhendu, Subhendu Biswas, and Sourangshu Mukhopadhyay. (2021) An alternative approach for binary to decimal conversion of frequency encoded optical data using MZI-SOA switch. J. Opt.1–14.

Takiguchi, Masato et al. All-optical InAsP/InP nanowire switches integrated in a Si photonic crystal. ACS Photon. 7(4), 1016 (2020).

Zhong, C., Li, J. & Lin, H. Graphene-based all-optical modulators. Front. Optoelectr. 13(2), 114–128 (2020).

Yankowitz, Matthew et al. van der waals heterostructures combining graphene and hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1(2), 112 (2019).

Kara, Abdelkader et al. A review on silicene—new candidate for electronics. Surf. Sci. Rep. 67(1), 1 (2012).

Acun, Adil et al. Germanene: The germanium analogue of graphene. J. Phys. Cond. Matter 27(44), 443002 (2015).

Zhao, C.-X. & Jia, J.-F. Stanene: A good platform for topological insulator and topological superconductor. Front. Phys. 15(5), 1–15 (2020).

Carvalho, Alexandra et al. Phosphorene: From theory to applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1(11), 1 (2016).

Ataca, C., Sahin, H. & Ciraci, S. Stable, single-layer MX2 transition-metal oxides and dichalcogenides in a honeycomb-like structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 116(16), 8983–8999 (2012).

Fu, Huixia et al. Multilayered silicene: the bottom-up approach for a weakly relaxed Si (111) with Dirac surface states. Nanoscale 7, 3815880 (2015).

Takeda, K. & Shiraishi, K. Theoretical possibility of stage corrugation in Si and Ge analogs of graphite. Phys. Rev. B 50(20), 14916 (1994).

Zhao, Jijun et al. Rise of silicene: A competitive 2D material. Prog. Mater. Sci. 83, 24 (2016).

Liu, G. et al. Is silicene stable in O2?—First-principles study of O2 dissociation and O2-dissociation–induced oxygen atoms adsorption on free-standing silicene. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 106(4), 47001 (2014).

Molle, Alessandro et al. Hindering the oxidation of silicene with non-reactive encapsulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23(35), 4340 (2013).

Tao, Li. et al. Silicene field-effect transistors operating at room temperature. Nat. nanotechnol. 10(3), 227 (2015).

Liu, G. et al. Comparison of the stability of free-standing silicene and hydrogenated silicene in oxygen: A first principles investigation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26(35), 355007 (2014).

Houssa, M. The rise of silicene. NPG Asia Mater. 7(6), e191–e191 (2015).

Kharadi, Mubashir A. et al. Sub-10-nm silicene nanoribbon field effect transistor. IEEE Trans. Electr. Dev. 66(11), 4976 (2019).

Ni, Zeyuan et al. Tunable bandgap in silicene and germanene. Nano let. 12(1), 113 (2012).

Li, Geng et al. Stable silicene in graphene/silicene Van der waals heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 30(49), 1804650 (2018).

Quhe, Ruge et al. Tunable and sizable band gap in silicene by surface adsorption. Sci. Rep. 2(1), 853 (2012).

Genser, Jakob et al. Optical signatures of dirac electrodynamics for hBN-passivated silicene on Au (111). Nano Lett. 21(12), 5301 (2021).

Gao, N., Li, J. C. & Jiang, Q. Bandgap opening in silicene: Effect of substrates. Chem. Phys. Lett. 592, 222–226 (2014).

Li, Linyang et al. Moiré superstructures of silicene on hexagonal boron nitride: a first-principles study. Phys. Lett. A 377(38), 2628 (2013).

Liu, H., Gao, J. & Zhao, J. Silicene on substrates: A way to preserve or tune its electronic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 117(20), 10353–10359 (2013).

Ferri, Matteo et al. Ab initio study of the structural, electronic, magnetic, and optical properties of silicene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 99(8), 085414 (2019).

Heidari, M., Ahmadi, V. & Darbari, S. Electronic and optical properties of single-walled silicon nanotubes: the sp3 tight-binding model. Modares J. Electr. Eng. 15(3), 27–31 (2015).

Chowdhury, S. & Jana, D. A theoretical review on electronic, magnetic and optical properties of silicene. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79(12), 126501 (2016).

Salimian, F. & Dideban, D. Comparative study of nanoribbon field effect transistors based on silicene and graphene. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 93, 92–98 (2019).

Li, Hong et al. High performance silicene nanoribbon field effect transistors with current saturation. Europ Phys. J. B. 85, 1–6 (2012).

Salimian, F. & Dideban, D. A silicene nanotube field effect transistor (sintfet) with an electrically induced gap and high value of Ion/Ioff. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 7, 1 (2018).

Sazzadur, Rahman Md. et al. Silicene quantum capacitance dependent frequency readout to a label-free detection of DNA hybridization—a simulation analysis. Biosensors 11(6), 178 (2021).

Kharadi, Mubashir A. et al. Silicene/MoS 2 heterojunction for high-performance photodetector. IEEE Trans. Electron. Dev. 68(1), 138 (2020).

Emami-Nejad, Hamed et al. A silicene-based plasmonic electro-optical switch in THz range. Phys. Scripta 98(1), 015803 (2022).

Emami-Nejad, H. et al. Proposal of an infrared electro-optic switch based on grapheme–silicone–graphene metamaterial with electrically dynamic tunability. Opt. Rev. 29(6), 476–486 (2022).

Wirth-Lima, A. J., Silva, M. G. & Sombra, A. S. B. Comparisons of electrical and optical properties between graphene and silicene—A review. Chin. Phys. B 27(2), 023201 (2018).

Pitarke, J. M. et al. Theory of surface plasmons and surface-plasmon polaritons. Rep. Prog. Phys. 70(1), 1 (2006).

Franzen, S. Surface plasmon polaritons and screened plasma absorption in indium tin oxide compared to silver and gold. J. Phys. Chem. C 112(15), 6027–6032 (2008).

Bludov, Yu. V. et al. A primer on surface plasmon-polaritons in graphene. Int. J. Modern Phys. B 27(10), 1341001 (2013).

Jensen, Erk. Cavity basics. arXiv preprint arXiv:1201.3202 (2012).

Mikhailov, S. A. & Ziegler, K. New electromagnetic mode in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99(1), 016803 (2007).

Emami-Nejad, Hamed, et al. Outstanding tunable electrical and optical characteristics in monolayer silicene at high terahertz frequencies. J. Comput. Electr. (2022): 1–9.

Menabde, Sergey G. et al. Direct optical probing of transverse electric mode in graphene. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 1 (2016).

Ukhtary, M. Shoufie. et al. Broadband transverse electric surface wave in silicene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109(6), 063103 (2016).

Kumar, Anshuman et al. Tunable light–matter interaction and the role of hyperbolicity in graphene–hBN system. Nano Lett 15(5), 3172 (2015).

Rajasekar, R., Parameshwari, K. & Robinson, S. Nano-optical switch based on photonic crystal ring resonator. Plasmonics 14(6), 1687–1697 (2019).

Tanaka, Yoshinori et al. Dynamic control of the Q factor in a photonic crystal nanocavity. Nat. Mater. 6(11), 862 (2007).

Guo, Zhongyi et al. Actively tunable terahertz switches based on subwavelength graphene waveguide. Nanomaterials 8(9), 665 (2018).

Dmitriev, V., Melo, G. & Castro, W. Tunable THz switch-filter based on magneto-plasmonic graphene nanodisk. IEEE Trans. Magn. 57(5), 1–9 (2021).

Molle, Alessandro et al. Silicene, silicene derivatives, and their device applications. Chemical Society Reviews 47(16), 6370 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. E-N. and Z.L. prepared figures and wrote the main manuscript text. A.M., A.F. and R.T. corrected and improved the details of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Emami-Nejad, H., mir, A., Lorestaniweiss, Z. et al. First designing of a silicene-based optical MOSFET with outstanding performance. Sci Rep 13, 6563 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33620-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33620-2