Abstract

70 kDa heat shock protein Hsp70 (also termed HSP70A1A) is the major stress-inducible member of the HSP70 chaperone family, which is present on the plasma membranes of various tumor cells, but not on the membranes of the corresponding normal cells. The exact mechanisms of Hsp70 anchoring in the membrane and its membrane-related functions are still under debate, since the protein does not contain consensus signal sequence responsible for translocation from the cytosol to the lipid bilayer. The present study was focused on the analysis of the interaction of recombinant human Hsp70 with the model phospholipid membranes. We have confirmed that Hsp70 has strong specificity toward membranes composed of negatively charged phosphatidylserine (PS), compared to neutral phosphatidylcholine membranes. Using differential scanning calorimetry, we have shown for the first time that Hsp70 affects the thermotropic behavior of saturated PS and leads to the interdigitation that controls membrane thickness and rigidity. Hsp70-PS interaction depended on the lipid phase state; the protein stabilized ordered domains enriched with high-melting PS, increasing their area, probably due to formation of quasi-interdigitated phase. Moreover, the ability of Hsp70 to form ion-permeable pores in PS membranes may also be determined by the bilayer thickness. These observations contribute to a better understanding of Hsp70-PS interaction and biological functions of membrane-bound Hsp70 in cancer cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) is a highly conserved member of the 70 kDa chaperone family HSP70 that performs many critical functions in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. The HSP70 family includes at least eight members that differ in amino acid residues in their domains and have some tissue-specific expression1. Hsp70 protein, also called HSP70A1A, consists of two domains: an N-terminal ATP-dependent nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (SBD), coupled with a flexible linker. It is a stress-inducible protein synthesized by the cell under stressful conditions (e.g., heat shock, hypoxia, ionizing radiation, oxidative stress, etc.). The functions of the Hsp70 in eukaryotic cells are quite diverse including the folding/refolding of misfolded proteins and polypeptides, protein translocation and degradation, regulation of the processes of apoptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagy2,3,4,5.

In addition to intracellular localization, Hsp70 is present on the plasma membranes of various solid and hematological malignancies, but not on the membranes of normal cells6,7,8. The exact mechanisms of Hsp70 anchoring to the lipid bilayer and protein functions are still not fully understood. The investigation of Hsp70 interaction with membrane components, its incorporation into lipid bilayer and externalization on the membrane surface is sophisticated due to the fact that protein does not contain any known transmembrane sequence. It is assumed that Hsp70 is transferred to the plasma membrane via non-classical vesicular mechanisms, since inhibitors of the classical ER-Golgi pathway do not affect membrane-bound Hsp70 (mHsp70) expression9.

Currently, several lipid components of the plasma membrane of tumor cells have been proposed as partners of Hsp70 for its anchoring on the membrane. One potential partner is the glycosphingolipid globoyltriaosylceramide (Gb3). Gb3 is a component of cholesterol-enriched lipid domains (termed lipid rafts) overexpressed in the membranes of tumor cells10,11,12. Staining of Gb3 and mHsp70 on tumor cells revealed their colocalization employing confocal microscopy13. Treatment of tumor cells with methyl-β-cyclodextrin, that preferentially affects cholesterol, led to a significant decrease in mHsp70 expression, which is consistent with previous assumptions about the presence of Hsp70 in lipid rafts14,15. Moreover, in vitro experiments with liposomes confirmed that Hsp70 predominantly binds to vesicles containing Gb313.

In addition to Gb3, Hsp70 is able to interact with negatively charged phosphatidylserine (PS) on the plasma membrane of tumor cells16,17. Under non-stress conditions, PS is located in the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer of normal cells, but under the influence of various stress factors, it moves to the outer leaflet through the activation of the Ca2+-dependent phospholipid scramblase and reduced the ATP levels, leading to a loss of PS asymmetry in the membrane18. Non-apoptotic tumor cells contain elevated level of surface PS regulated by differential flippase activity and intracellular calcium19. Hypoxia treatment of tumor cells causes colocalization of Hsp70 and PS on the cell surface, which is also observed when an exogenous protein is added to normoxic and hypoxic tumor cells17. Bilog et al.16 further proved the binding Hsp70 and PS localized in cytoplasmic leaflet of the membrane of tumor cells. This is consistent with the hypothesis that Hsp70 can be transferred through the membrane by flipping of PS from the inner to the outer leaflet20,21. This process may be followed by the rapid return of PS to the inner side of membrane by flippase, leaving the protein embedded in the bilayer22.

The specific interaction between PS and recombinant Hsp70 was also shown using liposomes of various compositions17,23,24,25,26,27,28, while interaction with neutral lipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) was weak and unspecific27,29. Hsp70, but not Hsp90, was able to selectively integrate into unilamellar palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylserine (POPS) vesicles, and this incorporation was proportionally reduced by decreasing the content of POPS25. Presumably, electrostatic Hsp70-lipid interactions are required only for the initial association with the plasma membrane, then anchoring is associated with the alignment of protein domains with acyl chains of dipalmitoylphosphatidylserine (DPPS)26,30. In support of the assumption, the association of Hsp70 with model membranes is enhanced by increasing the saturation level of PS fatty acid chains26,29. Alder et al.31 also reported that Hsp70 promotes the leakage of calcein from liposomes composed of mixture of soy phospholipids (neutral PC and phosphatidylethanolamine, and negatively charged phosphatidylinositol). This is most likely due to the ability of Hsp70 to form pores in the negatively charged lipid bilayers21,32. Another constitutive member of the HSP70 family, heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein (Hsc70) is capable of forming very stable and uniform ion conductance channels, and activity of these channels are regulated by the presence of ATP/ADP33. Moreover, Hsc70 and Hsp70 are able to aggregate POPS liposomes in a time- and concentration-dependent manner, which also depends on the content of ATP/ADP23.

In the current study we aimed to identify the lipid determinants for Hsp70 action on model membranes. The protein impacted thermotropic behavior of PS by inducing interdigitation. Hsp70 effects on domain organization of PS-enriched membranes was dependent on the PS acyl tail saturation. A dependence of the Hsp70 pore-forming ability on the PS content and the lipid bilayer thickness was demonstrated.

Results and discussion

Hsp70 induces the quasi-interdigitated phase in the membranes composed of phosphatidylserines

We studied the effect of Hsp70 on the thermotropic behavior of the neutral DMPC and negatively charged DMPS using differential scanning microcalorimetry. Figure 1a demonstrates the heating thermograms of DMPC in the absence (control, black curve) and in the presence of Hsp70 at concentrations of 80 (red curve) and 160 μg/mL (blue curve). Hsp70 did not affect the main thermotropic parameters of the DMPC at both concentrations (ΔTm, ΔT1/2, and ΔΔTh is about zero), confirming no interaction between protein and PC.

Figure 1b and Supplementary Table S1 demonstrates that Hsp70 was characterized by dramatic effects on the thermotropic behavior of DMPS, indicating a strong interaction of the protein with bilayer composed of negatively charged PS. The biphasic phase behavior of DMPS was observed in the presence of protein at various concentration: an addition of Hsp70 up to 80 μg/mL led to decrease in transition temperature (Tm), a subsequent increase in Hsp70 concentration up to 110 μg/mL caused an enhancement in Tm-value, which was practically stabilized at concentrations more than 110 μg/mL (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, Fig. 2 shows that the biphasic behavior was also reflected in the increase in the half-width of the DMPS transition peak (T1/2, b), the difference in the Tm-values between heating and cooling scans (Tm-hysteresis, ΔTh, c) and the transition enthalpy (ΔH, d) as the protein concentration increased (Supplementary Table S1). The observed biphasic effects might indicate that Hsp70 induces quasi-interdigitated phase (Fig. 3). It should be noted that Hsp70 did not practically affect the thermotropic behavior of TMCL and DPPG (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S2) that was consistent to the assumption that lipid interdigitation is due to specific interaction of the protein with the PS and it was not a result of nonspecific electrostatic interaction of Hsp70 with the anionic phospholipids.

The dependence of the parameters characterizing the thermotropic behavior of DMPS (black curves), DPPS (red curves), and equimolar mixture of DMPS/DPPS (50/50 mol.%) (blue curves) on Hsp70 concentration: (a) the melting temperature of heating scan (Tm); (b) the half-width of the main peak (T1/2), (c) the difference in the transition temperatures between heating and cooling scans (Tm-hysteresis, ΔTh), and (d) transition enthalpy (ΔH).

Interdigitation is a rearrangement of lipid molecules in bilayer, when the hydrophobic tails of the phospholipids from opposite membrane leaflets interlock and interpenetrate. This leads to a decrease in the membrane thickness, an increase in the membrane packing density, a change in surface electrostatic properties and interleaflet coupling34.

It is well known that the propensity of saturated PCs to interdigitate under chemical inducers enhances as the hydrocarbon chain length increases35. We hypothesized that DPPS having the longer acyl chains (16:0) compared to DMPS (14:0) would be easier to interdigitate upon Hsp70 addition, i.e. dependence of thermotropic characteristics on protein concentration will shift horizontally towards lower concentrations. In confirmation, the introduction of protein to a concentration of 110 μg/mL led to significant increase in Tm-value of DPPS (Fig. 2a, red curve, Supplementary Table S1) contrast to inefficiency of this concentration in the case of DMPS (Fig. 2a, black curve, Supplementary Table S1). The mixing short-tailed and long-tailed lipids should also promote interdigitation. The Hsp70-induced interdigitation in the equimolar mixture of DMPS/DPPS is clearly demonstrated by a dramatic increase in the enthalpy of transition with increasing protein concentration (Figs. 1d, 2d, Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, our assumption is consistent with the studies of Lamprecht et al.26.

Based on results, we suggest that, when inserted into the membrane, Hsp70 is able to induce interdigitation, thereby leading to a decrease in membrane thickness and an increase in the lipid packing density. Potentially, a protein could use this ability to facilitate membrane pore formation by adjusting the surrounding lipid bilayer to its own three-dimensional structure to decrease hydrophobic mismatch. Moreover, Hsp70-induced membrane interdigitation might also impact to resistance to anti-cancer therapy due to larger membrane rigidity and decreased permeability. Indeed, the accumulating evidence implicate that the HSPs stabilization of biological membranes might be linked to the cancer cells primary stress-sensing mechanisms36. In the observation by Tsuchiya et al.37 it was revealed that several agents including epigallocatechin gallate, resveratrol, genistein, apigenin and anticancer drug doxorubicin significantly rigidified the tumor cell model membranes, particularly in the hydrocarbon core than the membrane surface. This in turn influences the cancer cells sensitivity towards doxorubicin38. However, it is still an open question whether changes in the lipid composition and/or concomitant conformational changes of proteins anchored in the membrane directly lead to chemoresistance of cells. Thus, P-glycoprotein that effluxes drug molecules has been demonstrated to be highly sensitive to the changes of membrane rigidity39.

There are studies indicating the ability of some proteins to change the Tm of lipids and lead to membrane remodeling. For example, Nogo-66, which is a part of the extracellular domain of the neurite outgrowth inhibitor protein, is capable of inducing interdigitation in DMPC membranes40,41. Another protein which is believed to be involved in the rearrangement of the PS-enriched lipid bilayer is α-synuclein, is a presynaptic neuronal protein whose aggregation is related to the Parkinson’s disease42,43. High concentration of α-synuclein induces lateral expansion of lipid molecules, positive curvature in bilayer and membrane thinning via interdigitation44. Moreover, it has been shown that when bound to the membrane, α-synuclein is able to permeabilize lipid bilayer through the formation of pores or conductive ion channels45,46,47,48. Pore formation was observed both for the monomeric form of α-synuclein and for oligomers in negatively charged membranes composed of PS, phosphatidylglycerol, and phosphatidic acid, but not in neutral ones. It was found that some peptides, such as human antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin (LL-37), frog-skin antimicrobial peptide peptidyl-glycylleucine-carboxyamide, and N-terminal domain of the capsid protein cleavage product of the flock house virus, induce the formation of the interdigitated gel phase in lipid bilayers with different composition49,50,51,52.

An intriguing example of a membrane-active protein is Hsp12 from the yeast S. cerevisiae. Welker et al.53 showed that Hsp12 binds selectively to a negatively charged lipids such as phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylinositol, comparing with a positive charged or neutral one. Moreover, Hsp12 is able to alter the physicochemical characteristics of the membrane composed of phosphatidylglycerol, leading to the formation of a ripple phase structures. A possible mechanism for the effect of membrane-active proteins on the phase behavior of lipids is that proteins recognize lipid-packing defects and interacts with the membrane, which, in turn, rearranges its structure to maintain its own integrity44,54.

In cells, interdigitation can affect the processes of transduction of intracellular signals and the transport of molecules across the membrane. Mass spectrometry analyses of PC-3 prostate cancer cells and their released exosomes revealed a strong interdigitation between stearoyloleoylphosphatidylserine in the inner leaflet and the very-long-chain sphingomyelin species in the outer leaflet55. This cross-linking of lipids may contribute to PS clustering and influence on some functions of PS-binding proteins such as K-Ras, Rho GTPase Cdc42, Akt, etc.56,57,58. It has previously been reported that interdigitation occurs in membrane domains with a high lipid order and it may play a role in toxin-induced signaling59,60,61. For instance, it is assumed that bacterially produced Shiga toxin, when bound to Gb3 located in lipid rafts, can promote membrane interdigitation, leading to the interleaflet coupling between Gb3 and lipids from inner leaflet (potentially PS), which, in turn, transmit a signal to the cytoplasm. To deep insight the molecular mechanisms of Hsp70-PS interaction we examined the effects of PS-enriched ordered and disordered lipid domains.

Hsp70 potentiates ordered negatively charged domains

Confocal fluorescence microscopy was employed to detect the interaction of Hsp70 with PS in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) composed of POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) and POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%). Rh-DPPE was used as a fluorescent label, which prefers the disordered domain (Lα) and is excluded from the ordered lipid phase (So)62. Figure 4a shows typical micrographs of GUVs made from respective lipid compositions in the absence (control) and presence of Hsp70, as well as a statistical description of their domain organization. Approximately 65% of liposomes composed of POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) were homogeneously colored in the absence of Hsp70, while 35% of POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) vesicles demonstrated uncolored domains of irregular shape that were organized by a negatively charged DPPS. The addition of protein led to about 20% decrease and appropriate increase in the relative number of homogeneously colored vesicles and liposomes with uncolored So domains respectively, which might indicate the ability of Hsp70 to integrate into DPPS-containing liposomes and to stabilize the DPPS-enriched ordered domains. This observation can be easily rationalized by the above assumption of protein-associated quasi-interdigitated DPPS phase (Figs. 1c and 2, Supplementary Table S1). The probability of ordered domain appearance is related to high energetic cost of formation of So/Lα boundary due to a larger hydrophobic thickness of So domains than the surrounding Lα regions. Hsp70-induced DPPS interdigitation should lead to decrease in the hydrophobic mismatch and appropriate increase in the probability of ordered domain (Fig. 5).

Diagrams of percentage of phase separated vesicles with typical GUVs confocal micrographs (scale bar is equal to 10 µm) (a) and Ar (the ratio of the So domain area to the total GUV area) (b) in POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) and POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) samples before (control) and after Hsp70 addition. At least 10 experiments were performed for counting of percentage of phase separated vesicles, 150 ± 15 images were processed for Ar calculating. The significance is represented as nsp ≥ 0.05, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, and ****p ≤ 0.0001.

Schematic representation of the Hsp70 ability to reduce hydrophobic mismatch and facilitate formation of ordered domains via interdigitation. Hsp70 atomic structure has a PDB code 2KHO; negatively charged PS molecules in ordered lipid phase (So) are shown in red, neutral PC molecules in disordered domains (Lα) are shown in yellow.

Further we tested the ability of Hsp70 to influence phase separation in POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) mixture, where POPS is located in a disordered liquid phase, while the ordered phase is predominantly formed by neutral DPPC. Taking into account that, the protein cannot bind DPPC (Fig. 1a) and the presence of one unsaturated acyl chain should inhibit the protein-induced interdigitation of POPS-enriched Lα regions, we expected that an addition of Hsp70 into solution bathing POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) liposomes will not produce any noticeable effects. As expected, Fig. 4 shows that the addition of Hsp70 to vesicles composed of POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) did not practically affect lipid phase separation.

To further demonstrate a higher probability of formation of ordered domains in the presence of Hsp70 in POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) liposomes compared to its absence and inability of the protein to influence the lipid segregation in POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) vesicles we compared how the area of ordered domains in POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) and POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) vesicles varied after protein insertion (Fig. 4b). Using the ImageJ software, we determined the ratio of area of all So-domains to the total area of the liposome (Ar). The results revealed that Hsp70 led to 2.6-fold increase in the Ar in POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) but not in POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) vesicles, that once again indicated the ability of protein to interact with ordered DPPS-enriched phase and protein inability to influence disordered POPS-containing domains. The results may imply that in cancer cells Hsp70 is able to interact with negatively charged saturated PSs in lipid rafts. The incorporation of Hsp70 into the membrane and facilitation of PS interdigitation in ordered domains might trigger signaling cascades and affect the transduction of intracellular signals. Several studies point to a possible location of Hsp70 in lipid rafts13,14,63,64, but its biological functions and the exact anchoring mechanism are not yet fully understood. To try to clarify this issue, in future studies we are going to investigate the interaction of the protein with various raft-associated lipids such as ceramides, sphingomyelin, and gangliosides.

Hsp70 pore formation depends on the length of PS fatty acyl tails

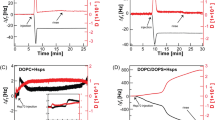

The effects of Hsp70 on the ion conductance of planar lipid bilayers composed of neutral POPC and negatively charged POPS, DOPS, and DPhPS were tested. The addition of the Hsp70 up to the concentration of 5.5 µg/mL to neutral POPC membranes did not lead to increase in the ion permeability of lipid bilayers (Fig. 6a). The subsequent enlargement in the Hsp70 concentration caused the violation in the electrical stability of lipid bilayers and their subsequent destruction occurred. Table 1 summarized the parameters referred to the effects of Hsp70 on the properties of phospholipid bilayers. Replacement of the neutral POPC for the negatively charged POPS led to formation of Hsp70 induced transmembrane pores with different amplitudes at concentration of 2.0 ± 0.5 µg/mL. Figure 6b demonstrates the typical examples of current fluctuations corresponding to openings and closures of single pores induced by Hsp70 in POPS membranes. The amplitude of observed step-like current fluctuations varied in the range from 1 to 20 pA at the transmembrane voltage of 100 mV. The further increase in the Hsp70 concentration more than 3.5 µg/mL resulted in a membrane destruction. The observed decrease in the protein threshold concentration in the POPS membranes compared to POPC bilayers and the different pattern of the lipid-protein interplays indicated a specific interaction of Hsp70 with negatively charged POPS.

Examples of records of transmembrane current fluctuations induced by Hsp70 in lipid bilayers composed of POPC (a), POPS (b), DOPS (c), and DPhPS (d) and bathed in 0.1 M KCl pH 7.4. Protein concentration was 5.0 µg/mL (a), 2.0 µg/mL (b), 4.5 µg/mL (c), and 2.0 µg/mL (d). The transmembrane voltage was equal to 100 mV. One experiment out of 3 replicates with essentially the same results is shown.

It is assumed that Hsp70 forms pores in the plasma membrane due to its ability to organize oligomers. In the absence of peptide targets and denatured proteins, Hsp70s tend to self-assemble to form low-order oligomers, regulated by ATP65,66. Apparently, after recognizing the negatively charged head groups of PSs, Hsp70 changes conformation, undergoes oligomerization, and is integrated into the lipid bilayer. It is considered that upon insertion, a fragment of the C-terminus of the SBD is exposed to the extracellular space, which was established using specific antibodies to various protein epitopes67. The N-terminus of Hsp70 is likely to remain in the cytoplasm, since the protein retains its nucleotide-binding function, and ATP/ADP regulate the opening and closing of ion channels21,33. The detected multilevel conductance of Hsp70-induced channels and different patterns of channel activity may indicate the incorporation of Hsp70 oligomers with different orders into the lipid bilayer. Clusters of β-sheets located in the SBD of Hsp70 may be responsible for oligomerization. So, β-amyloid peptides are able to form β-sheets that integrate into the membrane to form ion channels68,69.

To evaluate the effect of PS fatty acid chains on Hsp70-induced pore formation, besides POPS, characterizing by one saturated palmitoyl (16:0) tail and one unsaturated oleoyl (18:1) chain, bilayers composed of symmetrical DOPS, having two oleoyl tails, were also examined. The addition of Hsp70 to membranes composed of DOPS did not cause the appearance of step-like current fluctuations, only single detergent-like fluctuations of irregular profile were observed (Fig. 6c). The threshold concentration of protein for disintegration DOPS bilayers was about 4.4 µg/mL. These finding may point that Hsp70 could interact to DOPS but cannot form stable ion-permeable pores. This might be explained in the terms of pivotal role of membrane thickness and/or saturation of PS acyl chains in pore-forming ability of the protein. The hydrophobic regions which are thought to interact to membrane lipids were found at the C-terminus of the NBD70 and N-terminus of the SBD of Hsp7071. The possible dependence on the bilayer thickness is in a good agreement to an assumption of Hsp70-induced interdigitation (Fig. 7). Probably, the protein is able to form pores in membranes of defined thickness (with ≤ 16 hydrocarbon units), while an increase in the acyl tail length (up to 18) would inhibit this type of the protein activity. Hsp70-induced interdigitation might decrease hydrophobic mismatch and promote a formation of Hsp70 pores. Lipids with two unsaturated tails such as DOPS cannot be interdigitated by chemical inducers35, and Hsp70 cannot adjust the surrounding lipid media to hydrophobic thickness of its channels. Figure 6d demonstrates that Hsp70 also induced the step-like current fluctuations corresponding to openings and closures of single protein-induced pores in the membranes composed of DPhPS. This lipid characterized by two saturated 16:0 tails with four methyl branches (4CH3) in each other. The formation of pores in DPhPS bilayers at the same protein concentration range as in POPS bilayers does not confirm the hypothesis of specific interaction of Hsp70 with straight saturated (palmitoyl) chain, as methyl radicals should prevent the interaction. But these data do not contradict to the assumption of suitability of length of phytanoyl tails to hydrophobic length of Hsp70 channel. Moreover, the results of measuring the release of the fluorescent marker calcein from liposomes enriched with various PSs were in good agreement with the speculation that the protein is unable to form pores in membranes made from DOPC and DOPS (Supplementary Table S3).

Presumably, the ability of Hsp70 to form pores in the plasma membrane may play a role in the transport of various molecules (peptides, proteins, miRNAs) into or out of the cell by regulating the proper ionic environment. For example, Gross et al.72 proposed that penetration of the serine protease granzyme B into mHsp70-positive tumor cells is due to the formation of selective cation channels that facilitate the binding and absorption of granzyme B. In the absence of Hsp70 in the plasma membrane, these channels cannot be created and thus uptake of granzyme B is prohibited. The particular entry of granzyme B into mHsp70-positive cells mediates apoptosis in a perforin-independent manner73,74.

Conclusions

The present study confirmed the ability of Hsp70 to form ion-permeable pores in PS-enriched membranes, probably depending on the bilayer thickness. Moreover, we have shown for the first time that the chaperone individually influences the membrane domain organizations and the thermotropic characteristics of saturated PS, leading to the formation of quasi-interdigitated lipid phase. Certainly, this process might play a role in reducing the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiation and chemotherapy due to altered membrane rigidity. However, to clarify the pattern of interdigitation, small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering diffraction experiments are required. It should be noted that the described results were obtained for a recombinant human Hsp70 without taking into account Mg2+, Ca2+, K+ ions, ATP/ADP nucleotides, and co-chaperones, which make a significant contribution to the functioning of the protein under physiological conditions. Finally, detailed analysis of the possibility and the role in tumor pathogenesis of induction of interdigitated lipid domains in cell membranes by Hsp70 might reveal the mechanisms of cancer cell resistance and promote to the development of new therapeutic target agents.

Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were of reagent grade. Synthetic 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (POPS), 1,2-dioleyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS), 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DPhPS), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DMPS), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DPPS), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DPPG), 1′,3′-bis[1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-glycerol (TMCL), and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (Rh-DPPE) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Pelham, AL). Sorbitol, KCl, HEPES, KOH, calcein, Triton X-100, and Sephadex G-50 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd. (Gillingham, United Kingdom), phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was supplied by Rosmedbio (St. Petersburg, Russia). Solutions of 0.1 M KCl were buffered using 5 mM HEPES–KOH at pH 7.4.

Recombinant human Hsp70

Recombinant human Hsp70 was obtained from E. coli transformed with a pMSHSP plasmid75. Briefly, chaperone was purified with anion exchange chromatography employing DEAE-Sepharose (GE Healthcare, USA) with subsequent ATP-affinity chromatography using ATP-Agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) were depleted employing Polymyxin B-Agarose gel (Sigma) with the endotoxin content below 0.1 EU/mg Hsp70.

Differential scanning microcalorimetry

Differential scanning microcalorimetry experiments were performed by a μDSC 7EVO microcalorimeter (Setaram, Caluire-et-Cuire, France). Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) were prepared from pure DMPC, DMPS, DPPS, DPPG, TMCL and from mixture of DMPS/DPPS (50/50 mol.%) by the electroformation method using Vesicle Pre Pro@ (Nanion Technologies, Munich, Germany) (standard protocol, 3 V, 10 Hz, 1 h, 45 °C or 65 °C). The resulting liposome suspension contained 2 mM lipid and was buffered by 5 mM HEPES–KOH at pH 7.4. Hsp70 from 1 mg/mL PBS stock solution was added to aliquots at concentrations of 20, 40, 80, 110, 160, and 300 µg/mL (lipid:Hsp70 molar ratios were about 7200:1, 3600:1, 1800:1, 1350:1, 900:1, and 450:1 respectively). The liposomal suspension was heated and cooled at a constant rate of 0.2 and 0.3 °C/min, respectively. The reversibility of the thermal transitions was assessed by reheating the sample immediately after the cooling step from the previous scan. The temperature dependence of the excess heat capacity was analyzed using Calisto Processing (Setaram, Caluire-et-Cuire, France). The peaks on the thermograms were characterized by the maximum temperature of the main phase transition (Tm) of DMPC, DMPS, DPPS or DMPS/DPPS (50/50 mol.%) the half-width of the main peak (T1/2), characterizing the inverse cooperativity of the melting, the enthalpy of the main phase transition (an area of the main peak, ∆H), and the difference in the transition temperatures between heating and cooling scans (∆Th).

Confocal fluorescence microscopy of domain organization of giant unilamellar vesicles

GUVs were formed by the electroformation method on a pair of indium tin oxide slides with using a commercial Vesicle Pre Pro@ (Nanion Technologies, Munich, Germany) as previously described76. Lipid stock solutions of POPC/DPPS (80/20 mol.%) and POPC/POPS/DPPC (60/20/20 mol.%) were prepared in chloroform. Labeling was carried out by an addition of the fluorescent lipid probe, Rh-DPPE; its concentration in each sample was 1 mol.%. Rh-DPPE clearly favors liquid disordered phase (Lα) and it is excluded from ordered phase (So)62. The resulting aqueous liposome suspension containing 1 mM lipid and 0.5 M sorbitol was divided into 10 μL aliquots. Hsp70 from 1 mg/mL PBS stock solution was added to aliquots at concentration of 140 µg/mL (the lipid:Hsp70 molar ratio was about 500:1). The liposome suspension with Hsp70 was allowed to equilibrate for 30 min at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). The sample was observed as a standard microscopy preparation. 10 μL of the resulting liposome suspension without and with Hsp70 was placed on a standard microscope slide and covered by a cover slip. Vesicles were imaged through an oil immersion objective (PLAPON60XO, 60 ×/1.42 NA) using a confocal laser scanning microscope Olympus FV3000 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A helium–neon laser with a wavelength of 561 nm was used to excite Rh-DPPE. Temperature during observation was controlled by the air heating/cooling in the thermally insulated camera.

The percentage of vesicles (pi) with the respective phase separation type in each tested system was calculated as the ratio of phase-separated (coexistence of Lα and So) or homogenous (Lα only) GUVs to the total number of GUVs:

where the i-type of the phase separation scenario in GUVs indicates a homogeneously colored GUVs in the Lα-phase or liposomes with irregular uncolored So domains; Ni—number of vesicles with the i-th type of the phase separation scenario (from 0 to 150); and Nt—total number of counted vesicles in the sample (typically about 150). At least 10 independent experiments were performed with each lipid system.

To calculate the relative area of So domains in liposomes without and with Hsp70 (Ar), the obtained images (150 ± 15) were processed using ImageJ software (NIH, Washington, USA).

Registration of Hsp70 ion channels in planar lipid bilayers

Virtually solvent-free planar lipid bilayers were prepared according to a monolayer-opposition technique77 on a 50-µm-diameter aperture in a 10-µm thick Teflon film separating two (cis and trans) compartments of the Teflon chamber. The aperture was pretreated with hexadecane. The lipid bilayers were made from pure POPC, POPS, DOPS, or DPhPS. After the membrane was completely formed and stabilized, Hsp70 from a stock solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) was added to cis-compartments to obtain concentrations in the range from 0.1 to 6.0 µg/mL. All experiments were performed at room temperature (of 20 °C).

Ag/AgCl electrodes with 1.5% agarose/2 M KCl bridges were used to apply V and measure the transmembrane current (I). “Positive voltage” refers to the case in which the cis-side compartment is positive with respect to the trans-side. Transmembrane current was measured using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, LLC, Orleans Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in the voltage clamp mode. Data were digitized using a Digidata 1440A and analyzed using pClamp 10.0 (Molecular Devices, LLC, Orleans Drive, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Data were acquired at a sampling frequency of 5 kHz using low-pass filtering at 1 kHz, and the current tracks were processed through an 8-pole Bessel 100-kHz filter.

Each lipid system was characterized by the threshold concentration of Hsp70 required to appearance of the transmembrane ion-permeable pores (Csc) and the threshold concentration of Hsp70 required to reach the disintegration of the lipid bilayers (Ctr).

Calcein release from large unilamellar vesicles

Large unilamellar vesicles were prepared from pure POPC and DOPS, and a mixture of POPC/POPS (50/50 mol.%) and loaded with the fluorescent dye calcein (35 mM calcein, 10 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.4) by extrusion as previously described78. At this concentration calcein fluorescence inside the liposomes is self-quenched. Hsp70 from a stock solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) was added to calcein-loaded liposomes in concentration of 142 × 10−9 M (10 µg/mL), corresponding to the lipid:protein molar ratio of about 1300:1 (similar to the molar ratio used in the electrophysiological experiments). Time-dependence of calcein fluorescence de-quenching induced by 10 µg/mL of Hsp70 was measured over 20 min at 25 °C. The degree of calcein release was determined using a Fluorat-02-Panorama spectrofluorimeter (Lumex, Saint-Petersburg, Russia). The excitation wavelength was 490 nm and the emission wavelength was 520 nm.

The relative intensity of calcein fluorescence (RF, %) was calculated using the following formula:

where I and I0—calcein fluorescence intensity of the sample in the presence and absence of protein, respectively, and Imax—maximal fluorescence of the sample after lysis of all liposomes by Triton X-100. Factor of 0.9 was introduced in order to take into account a dilution of the sample by Triton X-100.

The characteristic parameters of calcein release from liposomes in the presence of protein were averaged from 2–3 experiments for each system (mean ± sd, p ≤ 0.05).

Statistics and reproducibility

The data were graphed and analyzed using Prism GraphPad 8 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). The values of Csc, Ctr, ΔTm, ΔT1/2, ΔΔTh, and ΔΔH were averaged from 2 to 4 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SE (p ≤ 0.05). The values of pi and Ar were averaged from at least 10 independent experiments and represent as mean ± SD (p ≤ 0.05). The data was verified for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. The statistical significance was evaluated by paired two-tailed t test. The significance was represented as nsp ≥ 0.05, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, and ****p ≤ 0.0001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author Dr. Maxim Shevtsov on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DMPC:

-

1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DMPS:

-

1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine

- DOPS:

-

1,2-Dioleyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine

- DPPC:

-

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DPPS:

-

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine

- DPhPS:

-

1,2-Diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine

- DPPG:

-

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol)

- TMCL:

-

1′,3′-Bis[1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-glycerol

- GUV:

-

Giant unilamellar vesicle

- Hsp70:

-

Heat shock protein 70 kDa

- NBD:

-

Nucleotide-binding domain

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- POPC:

-

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPS:

-

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine

- PS:

-

Phosphatidylserine

- Rh-DPPE:

-

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)

- SBD:

-

Substrate-binding domain

References

Murphy, M. E. The HSP70 family and cancer. Carcinogenesis 34(6), 1181–1188 (2013).

Kohler, V. & Andréasson, C. Hsp70-mediated quality control: Should I stay or should I go?. Biol. Chem. 401(11), 1233–1248 (2020).

Lang, B. J., Prince, T. L., Okusha, Y., Bunch, H. & Calderwood, S. K. Heat shock proteins in cell signaling and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1869(3), 119187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2021.119187 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Heat shock proteins and ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 864635. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.864635 (2022).

Morán Luengo, T., Mayer, M. P. & Rüdiger, S. G. D. The Hsp70-Hsp90 chaperone cascade in protein folding. Trends Cell Biol. 29(2), 164–177 (2019).

Shevtsov, M. et al. Membrane-associated heat shock proteins in oncology: From basic research to new theranostic targets. Cells 9(5), 1263 (2020).

Shin, B. K. et al. Global profiling of the cell surface proteome of cancer cells uncovers an abundance of proteins with chaperone function. J. Biol. Chem. 278(9), 7607–7616 (2003).

Thorsteinsdottir, J. et al. Overexpression of cytosolic, plasma membrane bound and extracellular heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) in primary glioblastomas. J. Neurooncol. 135(3), 443–452 (2017).

Hightower, L. E. & Guidon, P. T. Jr. Selective release from cultured mammalian cells of heat-shock (stress) proteins that resemble glia-axon transfer proteins. J. Cell Physiol. 138(2), 257–266 (1989).

Nutikka, A. & Lingwood, C. Generation of receptor-active, globotriaosyl ceramide/cholesterol lipid “rafts” in vitro: A new assay to define factors affecting glycosphingolipid receptor activity. Glycoconj. J. 20(1), 33–38 (2004).

Multhoff, G. et al. A stress-inducible 72-kDa heat-shock protein (HSP72) is expressed on the surface of human tumor cells, but not on normal cells. Int. J. Cancer 61(2), 272–279 (1995).

Robert, A. & Wiels, J. Shiga toxins as antitumor tools. Toxins 13(10), 690 (2021).

Gehrmann, M. et al. Tumor-specific Hsp70 plasma membrane localization is enabled by the glycosphingolipid Gb3. PLoS One 3(4), e1925. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001925 (2008).

Broquet, A. H., Thomas, G., Masliah, J., Trugnan, G. & Bachelet, M. Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J. Biol. Chem. 278(24), 21601–21606 (2003).

Triantafilou, M., Miyake, K., Golenbock, D. T. & Triantafilou, K. Mediators of innate immune recognition of bacteria concentrate in lipid rafts and facilitate lipopolysaccharide-induced cell activation. J. Cell Sci. 115, 26032611. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.115.12.2603 (2002).

Bilog, A. D. et al. Membrane localization of HspA1A, a stress inducible 70-kDa heat-shock protein, depends on its interaction with intracellular phosphatidylserine. Biomolecules 9(4), 152 (2019).

Schilling, D. et al. Binding of heat shock protein 70 to extracellular phosphatidylserine promotes killing of normoxic and hypoxic tumor cells. FASEB J. 23(8), 2467–2477 (2009).

Nagata, S., Sakuragi, T. & Segawa, K. Flippase and scramblase for phosphatidylserine exposure. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 62, 31–38 (2020).

Vallabhapurapu, S. D. et al. Variation in human cancer cell external phosphatidylserine is regulated by flippase activity and intracellular calcium. Oncotarget 6(33), 34375–34388 (2015).

De Maio, A. & Hightower, L. The interaction of heat shock proteins with cellular membranes: A historical perspective. Cell Stress Chaperones 26(5), 769–783 (2021).

Vega, V. L. et al. Hsp70 translocates into the plasma membrane after stress and is released into the extracellular environment in a membrane-associated form that activates macrophages. J. Immunol. 180(6), 4299–4307 (2008).

De Maio, A. Extracellular heat shock proteins, cellular export vesicles, and the Stress Observation System: A form of communication during injury, infection, and cell damage. It is never known how far a controversial finding will go! Dedicated to Ferruccio Ritossa. Cell Stress Chaperones 16(3), 235–249 (2011).

Arispe, N., Doh, M. & De Maio, A. Lipid interaction differentiates the constitutive and stress-induced heat shock proteins Hsc70 and Hsp70. Cell Stress Chaperones 7(4), 330–338 (2002).

Arispe, N., Doh, M., Simakova, O., Kurganov, B. & De Maio, A. Hsc70 and Hsp70 interact with phosphatidylserine on the surface of PC12 cells resulting in a decrease of viability. FASEB J. 18(14), 1636–1645 (2004).

Armijo, G. et al. Interaction of heat shock protein 70 with membranes depends on the lipid environment. Cell Stress Chaperones 19(6), 877–886 (2014).

Lamprecht, C. et al. Molecular AFM imaging of Hsp70-1A association with dipalmitoyl phosphatidylserine reveals membrane blebbing in the presence of cholesterol. Cell Stress Chaperones 23(4), 673–683 (2018).

McCallister, C., Kdeiss, B. & Nikolaidis, N. Biochemical characterization of the interaction between HspA1A and phospholipids. Cell Stress Chaperones 21(1), 41–53 (2016).

Dores-Silva, P. R., Cauvi, D. M., Kiraly, V. T. R., Borges, J. C. & De Maio, A. Human HSPA9 (mtHsp70, mortalin) interacts with lipid bilayers containing cardiolipin, a major component of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1862(11), 183436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183436 (2020).

Smulders, L. et al. Characterization of the relationship between the chaperone and lipid-binding functions of the 70-kDa heat-shock protein, HspA1A. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(17), 5995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21175995 (2020).

Mahalka, A. K., Kirkegaard, T., Jukola, L. T., Jäättelä, M. & Kinnunen, P. K. Human heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) as a peripheral membrane protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838(5), 1344–1361 (2014).

Alder, G. M., Austen, B. M., Bashford, C. L., Mehlert, A. & Pasternak, C. A. Heat shock proteins induce pores in membranes. Biosci. Rep. 10(6), 509–518 (1990).

Abkin, S. V. et al. Phloretin increases the anti-tumor efficacy of intratumorally delivered heat-shock protein 70 kDa (HSP70) in a murine model of melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 65(1), 83–92 (2016).

Arispe, N. & De Maio, A. ATP and ADP modulate a cation channel formed by Hsc70 in acidic phospholipid membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 275(40), 30839–30843 (2000).

Slater, J. L. & Huang, C. H. Interdigitated bilayer membranes. Prog. Lipid Res 27(4), 325–359 (1988).

Smith, E. A. & Dea, P. K. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Studies of Phospholipid Membranes: The Interdigitated Gel Phase. Applications of Calorimetry in a Wide Context—Differential Scanning Calorimetry, Isothermal Titration Calorimetry and Microcalorimetry (InTech, Paris, 2013).

Balogi, Z. et al. Hsp70 interactions with membrane lipids regulate cellular functions in health and disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 74, 18–30 (2019).

Tsuchiya, H. et al. Membrane-rigidifying effects of anti-cancer dietary factors. Biofactors 16(3–4), 45–56 (2002).

Alves, A. C. et al. Influence of doxorubicin on model cell membrane properties: Insights from in vitro and in silico studies. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 6343 (2017).

Eckford, P. D. & Sharom, F. J. Interaction of the P-glycoprotein multidrug efflux pump with cholesterol: Effects on ATPase activity, drug binding and transport. Biochemistry 47(51), 13686–13698 (2008).

Devanand, T., Krishnaswamy, S. & Vemparala, S. Interdigitation of lipids induced by membrane-active proteins. J. Membr. Biol. 252(4–5), 331–342 (2019).

Vasudevan, S. V., Schulz, J., Zhou, C. & Cocco, M. J. Protein folding at the membrane interface, the structure of Nogo-66 requires interactions with a phosphocholine surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107(15), 6847–6851 (2010).

Fusco, G., Sanz-Hernandez, M. & De Simone, A. Order and disorder in the physiological membrane binding of α-synuclein. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 48, 49–57 (2018).

Spillantini, M. G. et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388(6645), 839–840 (1997).

Ouberai, M. M. et al. α-Synuclein senses lipid packing defects and induces lateral expansion of lipids leading to membrane remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 288(29), 20883–20895 (2013).

Kim, H. Y. et al. Structural properties of pore-forming oligomers of alpha-synuclein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(47), 17482–17489 (2009).

Pandey, A. P., Haque, F., Rochet, J. C. & Hovis, J. S. α-Synuclein-induced tubule formation in lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 115(19), 5886–5893 (2011).

Zakharov, S. D. et al. Helical alpha-synuclein forms highly conductive ion channels. Biochemistry 46(50), 14369–14379 (2007).

Zhu, M., Li, J. & Fink, A. L. The association of alpha-synuclein with membranes affects bilayer structure, stability, and fibril formation. J. Biol. Chem. 278(41), 40186–40197 (2003).

Janshoff, A., Bong, D. T., Steinem, C., Johnson, J. E. & Ghadiri, M. R. An animal virus-derived peptide switches membrane morphology: Possible relevance to nodaviral transfection processes. Biochemistry 38(17), 5328–5336 (1999).

Pabst, G. et al. Membrane thickening by the antimicrobial peptide PGLa. Biophys. J. 95(12), 5779–5788 (2008).

Sevcsik, E., Pabst, G., Jilek, A. & Lohner, K. How lipids influence the mode of action of membrane-active peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768(10), 2586–2595 (2007).

Sevcsik, E. et al. Interaction of LL-37 with model membrane systems of different complexity: Influence of the lipid matrix. Biophys. J. 94(12), 4688–4699 (2008).

Welker, S. et al. Hsp12 is an intrinsically unstructured stress protein that folds upon membrane association and modulates membrane function. Mol. Cell 39(4), 507–520 (2010).

Varkey, J. et al. Membrane curvature induction and tubulation are common features of synucleins and apolipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 285(42), 32486–32493 (2010).

Llorente, A. et al. Molecular lipidomics of exosomes released by PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831(7), 1302–1309 (2013).

Cho, K. J. et al. Inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase depletes cellular phosphatidylserine and mislocalizes K-Ras from the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36(2), 363–374 (2015).

Fairn, G. D., Hermansson, M., Somerharju, P. & Grinstein, S. Phosphatidylserine is polarized and required for proper Cdc42 localization and for development of cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13(12), 1424–1430 (2011).

Huang, B. X., Akbar, M., Kevala, K. & Kim, H. Y. Phosphatidylserine is a critical modulator for Akt activation. J. Cell Biol. 192(6), 979–992 (2011).

Klokk, T. I., Kavaliauskiene, S. & Sandvig, K. Cross-linking of glycosphingolipids at the plasma membrane: Consequences for intracellular signaling and traffic. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73(6), 1301–1316 (2016).

Lingwood, C. A. et al. New aspects of the regulation of glycosphingolipid receptor function. Chem. Phys. Lipids 163(1), 27–35 (2010).

Russo, D., Parashuraman, S. & D’Angelo, G. Glycosphingolipid-protein interaction in signal transduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17(10), 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17101732 (2016).

Juhasz, J., Davis, J. H. & Sharom, F. J. Fluorescent probe partitioning in giant unilamellar vesicles of “lipid raft” mixtures. Biochem. J. 430(3), 415–423 (2010).

Chen, S., Bawa, D., Besshoh, S., Gurd, J. W. & Brown, I. R. Association of heat shock proteins and neuronal membrane components with lipid rafts from the rat brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 81(4), 522–529 (2005).

Zhu, Y. Z. et al. Association of heat-shock protein 70 with lipid rafts is required for Japanese encephalitis virus infection in Huh7 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 93, 61–71 (2012).

Benaroudj, N., Fouchaq, B. & Ladjimi, M. M. The COOH-terminal peptide binding domain is essential for selfassociation of the molecular chaperone Hsc70. J. Biol. Chem. 272(13), 8744–8751 (1997).

Gao, B., Eisenberg, E. & Greene, L. Effect of constitutive 70-kDa heat shock protein polymerization on its interaction with protein substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 271(28), 16792–16797 (1996).

Botzler, C., Li, G., Issels, R. D. & Multhoff, G. Definition of extracellular localized epitopes of Hsp70 involved in an NK immune response. Cell Stress Chaperones 3(1), 6–11 (1998).

Arispe, N., Rojas, E. & Pollard, H. B. Alzheimer disease amyloid beta protein forms calcium channels in bilayer membranes: Blockade by tromethamine and aluminum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90(2), 567–571 (1993).

Arispe, N., Rojas, E., Genge, B. R., Wu, L. N. & Wuthier, R. E. Similarity in calcium channel activity of annexin V and matrix vesicles in planar lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 71(4), 1764–1775 (1996).

Flaherty, K. M., DeLuca-Flaherty, C. & McKay, D. B. Three-dimensional structure of the ATPase fragment of a 70K heat-shock cognate protein. Nature 346(6285), 623–628 (1990).

Morshauser, R. C. et al. High-resolution solution structure of the 18 kDa substrate-binding domain of the mammalian chaperone protein Hsc70. J. Mol. Biol. 289(5), 1387–1403 (1999).

Gross, C., Koelch, W., DeMaio, A., Arispe, N. & Multhoff, G. Cell surface-bound heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) mediates perforin-independent apoptosis by specific binding and uptake of granzyme B. J. Biol. Chem. 278(42), 41173–41181 (2003).

Gehrmann, M. et al. Immunotherapeutic targeting of membrane Hsp70-expressing tumors using recombinant human granzyme B. PLoS One 7(7), e41341. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041341 (2012).

Shevtsov, M. et al. Granzyme B functionalized nanoparticles targeting membrane Hsp70-positive tumors for multimodal cancer theranostics. Small 15(13), e1900205. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201900205 (2019).

Shevtsov, M. A. et al. Effective immunotherapy of rat glioblastoma with prolonged intratumoral delivery of exogenous heat shock protein Hsp70. Int. J. Cancer 135(9), 2118–2128 (2014).

Ostroumova, O. S., Chulkov, E. G., Stepanenko, O. V. & Schagina, L. V. Effect of flavonoids on the phase separation in giant unilamellar vesicles formed from binary lipid mixtures. Chem. Phys. Lipids 178, 77–83 (2014).

Montal, M. & Mueller, P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69(12), 3561–3566 (1972).

Efimova, S. S. et al. Lipid-mediated regulation of pore-forming activity of syringomycin E by thyroid hormones and xanthene dyes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1860(3), 691–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.12.010 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement No. 075-15-2022-301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S., O.O., and S.E. conceived the concept of this study. A.I. and A.Z. carried out the protein purification and biochemical analyses. S.E. and R.T. performed all experiments and statistical tests. R.T. drafted the manuscript; all authors contributed to the manuscript editing. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tagaeva, R., Efimova, S., Ischenko, A. et al. A new look at Hsp70 activity in phosphatidylserine-enriched membranes: chaperone-induced quasi-interdigitated lipid phase. Sci Rep 13, 19233 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46131-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46131-x

This article is cited by

-

Fluorescence molecular imaging of high-grade gliomas and brain metastases using the RAS70 peptide targeting plasma membrane-bound Hsp70 on tumor cells

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2026)

-

Glioblastoma cell motility and invasion is regulated by membrane-associated heat shock protein Hsp70

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2025)