Abstract

Binding affinity is an important factor in drug design to improve drug-target selectivity and specificity. In this study, in silico techniques based on molecular docking followed by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were utilized to identify the key residue(s) for CSF1R binding affinity among 14 pan-tyrosine kinase inhibitors and 15 CSF1R-specific inhibitors. We found tryptophan at position 550 (W550) on the CSF1R binding site interacted with the inhibitors' aromatic ring in a π–π way that made the ligands better at binding. Upon W550-Alanine substitution (W550A), the binding affinity of trans-(−)-kusunokinin and imatinib to CSF1R was significantly decreased. However, in terms of structural features, W550 did not significantly affect overall CSF1R structure, but provided destabilizing effect upon mutation. The W550A also did not either cause ligand to change its binding site or conformational changes due to ligand binding. As a result of our findings, the π–π interaction with W550's aromatic ring could be still the choice for increasing binding affinity to CSF1R. Nevertheless, our study showed that the increasing binding to W550 of the design ligand may not ensure CSF1R specificity and inhibition since W550-ligand bound state did not induce significantly conformational change into inactive state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tyrosine kinases (TKs) regulate the signal transductions which control a wide range of fundamental cellular functions, including cell growth and proliferation, differentiation, migration, metabolism, and mortality1,2. At least 90 unique TK genes have been identified. In these numbers, 58 of them encode receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs)3. Dysregulation of RTK signaling impacts various diseases, especially cancer4, as they promote tumorigenesis5, migration6, as well as tumor angiogenesis7. Therefore, RTKs have emerged as therapeutic targets and clinical prognostic factors for cancer8,9,10.

Among 20 RTK subfamilies, RTK class III (PDGFR family) which includes PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, C-KIT, CSF1R, and FLT3, is highly expressed in various types of epithelial cancers9 and associated with poor prognosis11,12 via promoting tumor angiogenesis and metastasis1,6,12. The Colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R or FMS) is RTK class III that regulates immune responses13,14 and reproductive functions, including mammary gland development15 and regulation of ovulation rates16. The expression of CSF1R and its native ligand CSF-1 strongly correlates with oncogenesis and poor prognosis of breast carcinomas among other epithelial tumors17,18,19. Activation of CSF1R by CSF-1 triggers phosphorylation cascades such as PI3K-AKT, MAPK and STAT pathway20,21 which promote breast cancer cell proliferation22, metastasis23, and angiogenesis19, leading to the enhanced invasiveness of breast cancer17,18,19,24.

CSF1R-derived PI3K-AKT pathway induces c-myc gene expression, leads to upregulation of cyclinB, cyclinD, cyclinA and CDKs which drives cell cycle resulting in cancer cell proliferation and survival25. The MAPK pathway activates RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK, consequently phosphorylates transcription factors including RUNX which regulates expression of csf1r gene26. The expression of csf1r gene, which produces CSF1R and CSF1, is strongly associated with poor outcome in breast cancer and results in tumor cell invasiveness and pro-metastatic behavior both in patient and in vitro24,27,28,29,30,31,32. CSF1R activation also triggers the STAT1/3/5 pathways, which regulates several target oncogenes and affects cancer progression, proliferation, anti-apoptosis, metastasis, as well as chemoresistance and survival activities21,33,34.

Activation of CSF1R also enhances recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to the tumor site, hence the poor prognosis was observed23,35,36. The high expression levels of CSF1R and its ligand, CSF-1, have been found to correlate with poor prognosis in many cancer types such as breast carcinoma17,18,19,24,37, ovarian carcinoma38, lung adenocarcinoma39, gastric adenocarcinoma40, prostate adenocarcinoma41 and leukemia42. With PLX3397 (pexidartinib) been approved by the FDA for the treatment of tenosynovial giant cell tumor in 201943, pharmacological inhibition of CSF1R has emerged as a promising antitumor strategy. Therefore, targeting CSF1R with specific inhibitors has become an attractive therapeutic option and several CSF1R inhibitors are currently developed10,44,45.

The first pan-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib was approved by the FDA in 200146. It is commonly used as an RTK class III pan-inhibitor47. However, prolonged imatinib treatment may cause drug resistance via mutation in cancer cells48 as well as adverse effects due to its ability to also target other kinases49,50. Henceforth several single or dual-specific RTK class III inhibitors were developed, such as pexidartinib which was approved as CSF1R specific inhibitor by the FDA in 201943. However, one of the biggest challenges of designing a specific drug for RTKs is that the RTKs share similar protein structures1,3,8,51,52. Therefore, searching for new, lower toxic and higher target-specificity, TKIs is still of interest.

According to in silico molecular docking studies53,54 and in vitro si-RNA studies53, trans-(−)-kusunokinin, a lignan compound found in Piper nigrum35, targeted CSF1R, inhibiting the receptor and AKT signaling cascade, thus suppressing cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. Trans-(−)-kusunokinin inhibits cancer cell growth, proliferation and metastasis in a variety of cancer cell lines, including breast, colon and lung cancer cell lines55. The compound also reduces the size of breast tumors in mouse models without affecting body weight, internal organs, or bone marrow56. The synthetic racemic mixture trans-(±)-kusunokinin also showed anticancer activities against breast, colon, cholangiocarcinoma57 and ovarian cancer cell lines58 with low toxicity against normal cells59. The trans-(−)-kusunokinin was hypothesized to be the main active component in the racemic mixture, targeting proteins in proliferation and metastasis pathway, while trans-(+)-kusunokinin may additionally inhibit other related molecules. The differences in binding modes between the kusunokinin isoforms to CSF1R were noticed and the stereoselectivity of CSF1R for trans-(−)-kusunokinin over trans-(+)-kusunokinin was previously proposed54.

Since the ligand-induced conformational effect on the CSF1R could be the key understanding how the inhibitor triggered the CSF1R inhibition, however, the information about how inhibitor affected the CSF1R structurally remain unknown. In this study, we utilized in silico methods to visualize the significance of CSF1R-inhibitor interacting residues by performing molecular docking to compare the interacted residues and CSF1R specificity of pan-TKIs and CSF1R-specific inhibitors. In silico Alanine-mutagenesis and Molecular Dynamics simulation (MD) were also performed to elucidate the impact of interacted residue(s) on the ligand-receptor structural-activity relationships.

Results

Molecular docking in comparison of pan-TKIs and CSF1R-specific inhibitors

Fourteen pan-TKIs and fifteen single- or dual-CSF1R specific inhibitors (CID were provided in Table S1) were docked to CSF1R kinase domain 4R7H (www.rcsb.org/structure/4R7H) which originally bound to pexidartinib, the first FDA-approved CSF1R-specific inhibitor, to compare the binding affinity of the ligands. Prior to this docking procedure, all tested ligands were docked to CSF1R kinase domain in different states (as listed in Table S1) to verify if they were type-II TKIs which preferably bound the protein in inactive state (DFG-out) to active state (DFG-in), to reduce the possible error due to the CSF1R 4R7H conformation is in inactive state. All docked ligands showed better or similar binding energies to CSF1R inactive state than CSF1R active state (Table S2) and were proceeded to docked to the CSF1R 4R7H.

The docking score from the best binding pose, shown in Table 1, represented the binding energy of the ligand in CSF1R binding pocket and was used to interpret the binding affinity. The lower binding energy indicated the higher possibility of good binding affinity of the ligand to the protein.

Both pan-TKIs and CSF1R-specific inhibitors, showed good docking scores when docked to CSF1R 4R7H, indicated that they all possibly bound CSF1R. No significant differences in binding affinity were found between the two groups. Therefore, docking score alone was not enough to determine CSF1R-specificity. However, the differences in docking scores between each docked ligand were noticed.

Chiauranib, the pan-TKI targeted various angiogenesis-related kinases including CSF1R60, showed the best binding energies (docking scores = − 12.96 kcal/mol), followed by pan-TKI pazopanib61 and CSF1R specific inhibitor BPR1R02462 (docking scores = − 11.95 and − 11.67 kcal/mol, respectively). Interestingly, BPR1R024 and several pan-TKIs showed better binding energy than pexidartinib which had docking score = − 11.07 kcal/mol. Our compound of interest: trans-(−)-kusunokinin also showed better binding energy than pexidartinib while trans-(+)-kusunokinin showed lesser binding affinity (docking scores = − 11.47 and − 9.87 kcal/mol, respectively).

Surprisingly, pan-TKIs bound CSF1R with overall binding affinity better than CSF1R-specific inhibitors. The average docking score within pan-TKIs group was − 10.4479 kcal/mol whereas the average docking score within CSF1R-specificinhibitors group was − 9.6433 kcal/mol. The average docking score between all groups was − 10.0871 kcal/mol.

Using the average docking score between all groups as a cut-off, 8 out of 14 pan-TKIs shower high binding affinity to CSF1R kinase. On the other hand, only 4 out of 15 specific CSF1R inhibitors pass the cut-off. Trans-(−)-kusunokinin showed higher binding affinity than the cut-off whereas trans-(+)-kusunokinin binding affinity, in contrast, was below the cut-off. Interaction analysis was performed to identify the binding residue(s) that influenced the ligand binding affinity.

Interacted residue frequency revealed key residue for good binding affinity

Binding pose of each docked ligand with the lowest binding energy and the same binding site to pexidartinib were consequently subjected to interaction analysis. Interacted residues were listed in Table S3. Most of the docked ligands were found to form H-bond with Cysteine position 666th which is the ATP-binding residue63 (20 out of 31 ligands), followed by Glutamic acid position 664th and Asparagine position 796th of the DFG motif44 (11 out of 31 each). Some other frequently found interacted residues were Glutamic acid position 633rd (formed H-bound with 8 out of 31 docked ligands), Arginine position 549th, Leucine position 588th and Asparagine position 670th (each residue formed H-bound with 5 out of 31 docked ligands).

Six docked ligands formed either π–π or π–T shape with Tyrosine position 665th (Y665). However, among these 6 ligands, only imatinib which formed π–π interaction with Y665 in addition to π–π stacking with W550 and π–T shape with F797 had binding affinity above the cut-off (Table S3).

It was found that Phenylalanine position 797th (F797) of the conserved DFG-motif44 formed either π–π or π–T shape with 16 out of 31 ligands (Table 2) but with no notable correlation with the ligand binding energy (6 ligands were above the cut-off, 10 ligands were below the cut-off). So, it was though that although F797 was a mandatory interacted residue for ligand binding in CSF1R pocket, it had no impact on CSF1R binding affinity.

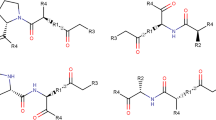

On the contrary, Tryptophan position 550th (W550) of the CSF1R juxtamembrane domain44,63 was noticed to form π–π stacking with 11 out of 31 docked ligands (Table 2). In these numbers, 10 of them were above the cut-off. It was even more obvious in CSF1R specific inhibitors group which all the 4 specific CSF1R inhibitors that pass the cut-off formed π–π stacking with W550 while none of the 11 ligands below the cut-off interacted with W550. Trans-(−)-kusunokinin which showed better binding energy than trans-(+)-kusunokinin also bound CSF1R at W550 while trans-(+)-kusunokinin bound CSF1R at F797. Figure 1 depicted the π–π stacking from the bound ligand with W550. Therefore, W550 was chosen to perform Alanine mutagenesis to validate the impact of this residue.

π–π stacking from the bound ligand with W550 in CSF1RWT. (A) Trans-(−)-kusunokinin (black), (B) Trans-(+)-kusunokinin (red), (C) Pexidartinib (blue), and (D) Imatinib (green) were depicted and the dash line indicated π–π interaction between the amino acid and the ligand. The protein and ligand structures were generated using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software version 1.9.3

Alanine mutagenesis

To investigate the significance of interaction at CSF1R W550, W550 was replaced with Alanine (CSF1RW550A), which omits the aromatic side chain while retaining the main-chain conformation and charges. Following the introduction of mutations, the side chain and protein folding were optimized. Structural changes upon mutation were examined and found that the mutation led to destabilizing effects64 on the protein (ΔΔG = + 2.23696 kcal/mol).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations analysis

Although molecular docking is a useful tool to investigate ligand–protein binding characters65,66, it cannot predict protein conformational changes upon ligand binding or kinetics due to docking procedures performed on a rigid protein model. Therefore, MD simulations were performed to evaluate the binding interaction that would occur in nature67,68,69,70,71,72. Widely used pan-TKIs: imatinib45,46 was chosen as a representation of pan-TKIs group while pexidartinib represented specific CSF1R inhibitor43, compared to our compounds of investigation: trans-(−)-kusunokinin and trans-(+)-kusunokinin. MD trajectories were obtained and proceeded to post-MD analysis.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)

First, RMSD was used to ensure that the complexes remained stable throughout the simulations. The RMSD analysis, illustrated in Fig. 2, revealed that every tested ligand remained in the pocket consistently throughout the simulations.

Root-mean square distance (RMSD) plot of the protein backbone. (A) Trans-(−)-kusunokinin in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (B) Trans-(+)-kusunokinin in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (C) Pexidartinib in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (D) Imatinib in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (E) Ligand-free CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). The values were calculated from three independent simulation systems and represented as mean values.

It was found from Fig. 2A and C that mutation W550A leaded to instability of the trans-(−)-kusunokinin-CSF1RW550A complex after 50 ns of simulations and imatinib-CSF1RW550A complex over the last 25 ns of simulation time, compared to CSF1RWT (Fig. 2E). Trans-(+)-kusunokinin also showed subtler climb-up fluctuations in the backbone RMSD after 50 ns of simulations in both models (Fig. 2B). However, the values are still within an acceptable range to be deemed stable enough to determine conformational changes upon ligand binding (RMSD larger than 3.0 Å)65. Pexidartinib, on the other hand, dissipated stable binding complexes throughout the simulation both in wild-type and mutant models (Fig. 2D).

Apart from the binding stability via the view of RMSD and ligand distance, fluctuations of protein residues upon ligand binding were evaluated with the RMSF of the α-carbon in each amino acid residue to determine the stability of the system as well as indicate the interacting residues that ligands are bound to. The original and re-arranged residue numbers were paired as shown in Table S4.

The RMSF patterns of CSF1RWT and CSF1RW550A were similar for all tested ligands (Fig. 3). This implied that the ligand binding could contribute no significant effect on the CSF1R structure flexibility, in all WT, mutant and ligand-free forms.

Root-mean square fluctuation (RMSF) plot of the α-carbon position in the protein backbone. (A) Trans-(−)-kusunokinin in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (B) Trans-(+)-kusunokinin in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (C) Pexidartinib in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (D) Imatinib in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (E) Ligand-free CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). The values were calculated from three independent simulation systems and represented as mean values. Residue numbers were re-arranged according to AMBER procedure.

CSF1R conformational change upon alanine mutagenesis

Although the mutation W550A led to destabilizing effects on the protein (ΔΔG = + 2.23696 kcal/mol), calculated with FoldX command, it did not change the protein conformation. The conformation alignment of ligand-free CSF1RWT and CSF1RW550A MD simulations in Fig. 4 showed to be resemble. The average distance pattern from protein center to the backbone of each residue also indicate no significant conformational changes (Fig. 5).

Alignment of ligand-free CSF1R kinase structure. Yellow structure represented CSF1RWT and grey structure represented CSF1RW550A. Blue sticks represented the native residue W550 of CSF1RWT and red sticks represented the mutated residue A550 of CSF1RW550A. Circle highlighted the substituted site. The protein structures were generated using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software version 1.9.3

Distances between center of ligand and center of protein during simulations

The distance between the ligand center of mass and the protein center of mass was plotted along the simulation to visualize the ligand's binding characteristics towards the protein. This could be investigated to see if the W550A mutation could repel the ligand or change its position in the CSF1R inhibitor binding pocket (Fig. 6).

Distances between center of ligand and center of protein during simulations. (A) Ligand-CSF1RWT models and (B) Ligand-CSF1RW550A models. Distances between trans-(−)-kusunokinin to protein models were represented in black, trans-(+)-kusunokinin in red, imatinib in green and pexidartinib in blue. The values were calculated from three independent simulation systems and represented as mean values.

The constant distance of trans-(−)-kusunokinin into the protein center, as well as imatinib and pexidartinib in both WT (Fig. 6A) and mutant CSF1R forms (Fig. 6B), suggested that all these compounds could remain in the CSF1R pocket. As a result, the W550A mutation may not have as strong an effect on the remnant drug characteristic binding in the CSF1R pocket as previously thought34. In other words, the W550A mutation had no effect on ligand locking in CSF1R. The greater distance of trans-(+)-kusunokinin to the protein center in both WT and mutant compared to other ligands, on the other hand, supported a previous study54 that the trans-(+)-kusunokinin may not preferentially bind the CSF1R-inhibitor site.

CSF1R conformational change upon ligand binding

Distance patterns were analyzed to see conformational changes in terms of movement of residue α-carbon from their original binding-free position to ligand-bound position. Difference in distance pattern between WT and W550A was plotted compared to original binding-free position (Fig. 7). Differences in distance pattern between WT and W550A more than 1.5 Å were counted as a slight conformational change upon ligand-binding due to W550A mutagenesis and more than 2.0 Å were counted as significant conformation changes (Table S5). These cut-offs were based on the distance which amino acid possibly form or loss their original interaction (interacted residue distance range from H-bond at 2 Å to hydrophobic interaction at 4 Å)73.

Difference in distance patterns upon ligand-binding between ligand-bound CSF1RWT and ligand-bound CSF1RW550A, calculated from the ligand-free models. (A) Trans-(−)-kusunokinin in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (B) Trans-(+)-kusunokinin in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (C) Pexidartinib in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). (D) Imatinib in complex with CSF1RW550A (red) or CSF1RWT (black). The light blue highlighted the activation loop (AL) region. The zero line represented the position of each residue from ligand-free CSF1R models. Minus values indicated that residues moved closer to the protein center while plus values indicated that residues moved further from the protein center. Similar distance patterns suggested no conformational changes between the two models. Differences of distance pattern more than 2.0 Å were counted as significant conformation changes due to mutation W550A.

Interestingly, trans-(−)-kusunokinin showed only slight W550A mutagenesis impacted on residue number 70–78 (Fig. 7A). These residues were move closer to the center of protein mass, however, none of these residues were significantly affected by the mutation W550A. On the other hand, W550A significantly impacted amino acid position 603rd–609th (residue 55–61), especially Lysine position 606th (residue 58) in binding to trans-(+)-kusunokinin (Fig. 7B). Imatinib and pexidartinib also showed close to none W550A mutagenesis impacted on CSF1R conformational change upon ligand-binding.

DFG-in and DFG-out conformation analysis

X-ray crystal structures reveal remarkable conformational heterogeneity, with active (on state) and inactive (off state) conformations. When the protein is active, the aspartate of the DFG motif engages the ATP-binding site and coordinates two Mg2+ ions. The activation loop has an open and extended shape63,74. An active state conformation is also distinguished by the orientation of the C helix, which is located on the N-terminal domain44. In an active conformation, it rotates inward toward the active site, followed by a characteristic ion-pair interaction between the conserved Glu of the C helix and the Lys of the N lobe's strand74,75,76. Imatinib binds to the new allosteric pocket in this DFG-out conformation, sparking a great deal of interest in developing inhibitors that specifically target the inactive DFG-out conformation77,78.

Inhibition of CSF1R was indicated by the position of DFG-motif which move Asparagine position 796th (D796) away from ATP-binding site, lead to DFG-out state or inactive state due to catalytic incomplete thus open an allosteric pocket adjacent to the ATP-binding pocket, which usually is the binding pocket of type II TKIs63. The α-carbon distance between Asparagine position 783rd (D783) following the HRDxxxN motif and Phenylalanine position 797th (F797) of the DFG motif were represented as d1. The α-carbon distance between the conserved Glutamic acid position 633rd (E633) on the αC-helix and F797 of the DFG motif were represented as d2.

These distances were used to interpret CSF1R state which considered DFG-out or inactive state when d1 < d2 and considered DFG-in or active state when d1 > d2. The classical DFG-out conformation cut-off at d1 < 7.2 Å and d2 > 9 Å61,63. The average distance d1 and d2 of each ligand–protein systems were averaged from the last 800 snapshots from the triplicated MD simulations and summarized in Table 3. The d1 and d2 of each MD simulations, as well as the difference in d1 and d2 upon mutation W500A, were provided in Table S6.

All tested ligand showed binding and preserving CSF1R in inactive DFG-out conformation without significant mutagenesis impact. The two reference ligands: imatinib and pexidartinib bound CSF1R in the classical DFG-out state while trans-(−)-kusunokinin and trans-(+)-kusunokinin showed slightly greater d1than the cut-off, indicated that these two compounds bound CSF1R in alternative (nonclassical) DFG-out inactive conformations. Moreover, trans-(+)-kusunokinin showed distance of d2 > 10.5 Å, therefore the binding conformation should be considered as αC-out conformation62, emphasized that trans-(+)-kusunokinin had different binding mode than trans-(−)-kusunokinin.

Relative binding free energies

Even though the structure parameter informed the binding characteristics of all studied ligands, the affinity had to be evaluated as the different binding site cannot assume the less binding affinity. The Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA)79,80 was thus used to calculate the ligand–protein complex's relative binding free energy. The free binding energies indicate how likely the ligand is to fit into the protein's binding pocket. Each system's MM/GBSA energies were calculated using three independent simulations and represented as mean standard error of mean (SEM). The statistical significance of binding free energy changes upon mutation was determined using the student's t-test (p-value < 0.05). All energies were reported in Table 4.

The substitution of W550 for Alanine did, in fact, have a significant effect on ligand binding to CSF1R. The mutation W550A reduced trans-(−)-kusunokinin and pexidartinib binding affinity to the CSF1R pocket while increasing trans-(+)-kusunokinin and imatinib binding. However, in both systems, the higher binding ability of trans-(+)-kusunokinin after mutation did not exceed trans-(−)-kusunokinin binding to the protein.

Off-target effects of trans-kusunokinin

Both trans-(−)-kusunokinin and trans-(+)-kusunokinin were analyzed for off-target predictions using Protox 3.0 for cytotoxicity (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/), SwissADME for drug-likeness (http://www.swissadme.ch/), and SwissTargetPrediction for drug-target prediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/). The off-target effects of these compounds are summarized in Figs. S1, S2, S3 and S4, respectively. In conclusion, both compounds exhibited the expected low toxicity and acceptable drug-likeness. The findings indicated that both trans-(−)-kusunokinin and trans-(+)-kusunokinin could be promising for the next stage of development.

Discussion

CSF1R-inhibitor interactions and modes of action

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are crucial in regulating normal cellular function1,2. Numerous evidence linked malfunction of RTKs to various diseases, especially cancer4. The Colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R or FMS) is RTK class III which strongly correlates with oncogenesis and poor prognosis of many types of cancer, including breast carcinomas17,18,19. Upon binding of its ligands: CSF-1 or IL-34, dimerization and activation of CSF1R consequently catalyzes the transfer of ATP phosphate to its tyrosine residue44,63, thus triggers breast cancer cell proliferation22,25, metastasis23,31, and angiogenesis19 pathways.

Since the first pan-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib was approved by the FDA in 200146. TKIs with increased specificity and selectivity toward either single RTK target or multiple RTK targets have become a major area of anticancer drug discovery in the past 20 years8,10. CSF1R inhibitors are also rapidly developed10,44,45. Among numerous lead compounds, pexidartinib is the first small-molecule inhibitor targeting CSF1R specifically that is approved by the FDA in 201943.

In this study, 14 pan-TKIs and 15 single or dual CSF1R-specific inhibitors were sampling to perform Molecular docking with CSF1R kinase domain crystalized structure to see if there are any correlation between the binding energy, which interpreted from the docking score, and the specificity of the ligand. As expected, although Molecular docking is a useful tool in drug discovery process, one of its limitations is that the calculated docking score from the rigid ligand and rigid protein docking is not necessarily relevant to the specificity or selectivity of the ligand tested in living organisms66. Therefore, it is not surprising to see that some of the pan-TKIs had better docking scores than CSF1R-specific inhibitors tested in this study.

We found that CSF1R’s Tryptophan position 550th is conserved across most species82 and various CSF1R inhibitors were designed based on the π–π interaction with the receptor, with W550 being the common interacting residue54,83,84,85,86,87. Based on this information, we have tried to elucidate and investigate the effect of the W550 and mutated ones on the drug-CSF1R interaction, as well as the effect on the structure of CSF1R. Due to this lack of these information, our study could provide more insight for the drug design guide based on W550, not only the binding enhancement but also the structural information of ligand bound CSF1R. However, the binding pose and interaction analysis gave us information on how to improve ligand binding affinity via structural-based drug development practices. It was revealed that π–π interaction between aromatic ring of the ligands and W550 significantly enhanced the binding affinity of the ligand to CSF1R kinase domain. Since several TKIs were developed based on a pyrimidine core due to its electron-rich aromatic heterocycle structure is obliged to many human RTKs87, the π–π stack interaction between the aromatic ring of W550 and aromatic structure of the inhibitor should be considered in CSF1R-structure based design drug process.

Aromatic-aromatic interactions greatly contribute to protein stability, protein–ligand interactions, catalysis, among other protein activities in cells, as they play a major role in chemical and biological recognition88,89,90,91. A typical π–π interaction has an energy between − 0.5 to − 2.0 kcal/mol92. The π–π interactions, together with hydrogen bonds, are commonly involved in anchoring drugs in many proteins and importantly contribute to the ligand binding affinity91,92,93,94. In an auto-inhibit state, the CSF1R residue W550 interacts with the carbonyl group of D796 thus stabilizing the DFG-out conformation of the activation loop, maintaining CSF1R in a catalytically inactive state which opens an allosteric pocket adjacent to the ATP-binding pocket. The allosteric pocket located in the kinase domain of the receptor. This allosteric pocket, together with the inward ATP binding site, is the classical binding pocket of the type II TKIs. One of the important interacted residues commonly found in CSF1R-inhibitor complex is W550 in the JM region of the kinase. Functionally, the residue is crucial for maintaining the autoinhibitory state of CSF1R by preventing the activation loop switch to an active conformation. Many CSF1R inhibitors were also designed based on the pyrimidine-core87,95,96,97 which contain an aromatic ring that favorably form π–π interactions with the aromatic side chain in CSF1R binding pocket, for example, with W55054,83,84,85,86,87.

Kusunokinin and W550 binding possibility

Trans-(−)-kusunokinin, isolated naturally from Piper nigrum55, has structure resemble to those pyrimidine ring-core inhibitors. It inhibits cancer cell growth, proliferation, and metastasis in a variety of cancer cell lines, including breast, colon and lung cancer cell lines55. The compound also reduces the size of breast tumours in mouse models without affecting body weight, internal organs, or bone marrow56. According to in silico molecular docking studies and in vitro si-RNA studies, trans-(−)-kusunokinin targeted CSF1R, inhibiting the receptor and AKT signalling cascade, and thus suppressing cancer cell proliferation and metastasis53,54.

A racemic mixture of trans-(−)-kusunokinin and trans-(+)-kusunokinin was obtained from the synthesis process, however, trans-(+)-kusunokinin, in contrast with its trans-(−)-isomer, showed no inhibitory effects against cancer cells98. Nonetheless, the racemic mixture trans-(±)-kusunokinin retained anticancer activities against breast, colon, cholangiocarcinoma57 and ovarian cancer cell lines58 with low toxicity against normal cells59. Therefore, trans-(−)-kusunokinin was hypothesised to be the main active component in the racemic mixture, targeting protein in proliferation and metastasis pathway, while trans-(+)-kusunokinin may additionally inhibited other related molecules54, given that the mechanism of action between trans-(−)-kusunokinin, trans-(±)-kusunokinin, and CSF1R inhibitor pexidartinib were different53.

Previously, the stereoselectivity of CSF1R for trans-(−)-kusunokinin over trans-(+)-kusunokinin was proposed due to (1) the CSF1R narrow binding pocket requiring planar arrangement of the binding ligand and (2) the π–π interaction between the W550 and the aromatic ring of the ligand being critical to form a stable ligand-CSF1R complex54. In both previous study54 and this current study, Molecular docking and MD simulations demonstrated that trans-(+)-kusunokinin could not fit into the binding pocket of CSF1R and thus could not form an interaction with W550, its binding affinity was much lower than that of trans-(−)-kusunokinin.

Taken together, we therefore continue our studies by utilizing in silico methods to further explore the significance of CSF1R W550 to the ligand binding affinity and the impact of this residue on CSF1R conformational change upon ligand binding, given that W550 regulates CSF1R activation structurally by interacting with the carbonyl group of the Aspartic acid position 796th (D796) of the DFG-motif, which stabilises the DFG-out conformation of the activation loop and thus keeps CSF1R inactive63,74,99. Trans-(−)-kusunokinin, as well as other inhibitors may stabilise the ligand-CSF1R complex and lock CSF1R in an inactive state via binding W550, among other residues. A shorter MD simulation time than in our previous study54 was used to ensure that the ligand remained within the binding site throughout the simulations, as we wanted to look at the interactions and conformational changes that occur when binding.

The possible stereoselectivity of CSF1R which prefers trans-(−)-kusunokinin to trans-(+)-kusunokinin was reported in54. In short, it was previously found that trans-( ±)-kusunokinin racemic mixture exhibited anticancer activities on breast cancer cell lines via partially bound and inhibited CSF1R53. The in silico simulations showed that the trans-(–) isomer bound CSF1R with stronger binding energy than the trans-(+) isomer and the complex of trans-(−)-kusunokinin-CSF1R was also more stable than trans-(+)-kusunokinin-CSF1R complex due to trans-(−)-kusunokinin forming π–π interaction with CSF1R W550's aromatic ring while trans-(+)-kusunokinin did not54. The work concluded that (1) W550 is the selective residue determine the kusunokinin enantiomer residence time within the CSF1R binding pocket and (2) the trans-(–) isomer was the main active component within the trans-(±)-kusunokinin racemic mixture which exhibited anticancer activities via binding and inhibition of CSF1R, while trans-(+) isomer possibly targeted additional molecules in breast cancer progression pathways. In this study, we aim to elucidate the impact of interacted residue(s) on the ligand-receptor binding features including binding affinity, target specificity, as well as the ligand-receptor structural-activity relationships.

Wild type and W550A structural effect due to ligand binding

Nevertheless, the Alanine mutagenesis and the Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations results demonstrated that W550 might not played important roles in CSF1R conformational change upon ligand binding, not in term of ligand binding features nor crucial for locking CSF1R into an inactive state. Substituting W550 with Alanine which omits of its aromatic side chain did not affect the movement of DFG-motif which indicate active or inactive state of CSF1R. Although minor conformational changes upon mutation were detected, they were not enough to cause ligand unbound from its original binding pocket. All tested compounds still bound CSF1R in inactive state without significantly structural differed from the WT.

There is currently no report on W550 mutation in CSF1R. The residue is conserved among type-III RTKs, except for FLT-3 which has Leucine instead of Tryptophan82. W550 is a critical residue for maintaining the autoinhibitory state of CSF1R by interacting with the carbonyl group of D796 thus preventing the activation loop switching to an active conformation. The stabilized DFG-out conformation of the activation loop consequently maintains CSF1R in a catalytically inactive state which opens an allosteric pocket adjacent to the ATP-binding pocket63,86,100. Therefore, by removing W550 side chain, CSF1R may be unable to maintain its auto-inactive state hence hyperactivity. However, from the predicted protein stability calculated from FoldX, the mutation W550A could lead to destabilizing effects on the protein, but not enough to cause protein miss-folding or conformation changes in ligand-free state, the CSF1RW550A was still in an auto-inhibit state as the template model CSF1RWT, as the alignment results showed in Figs. 4 and 5.

However, MM/GBSA results showed that W550A indeed affected the binding energies of trans-(−)-kusunokinin, trans-(+)-kusunokinin and imatinib significantly while not affected the binding energy of pexidartinib. The binding energy of trans-(−)-kusunokinin was significantly worsen upon mutation, indicated that trans-(−)-kusunokinin binding character was abundantly rely on the π–π stack interaction between its benzene ring and W550. In contrast, binding energies of trans-(+)-kusunokinin and imatinib were improved upon mutation. Since W550 is a conserved residue in TKR type III63, it is not surprising that the disappearance of W550 could affect imatinib binding affinity, despite that imatinib is a pan-inhibitor.

On the other hand, pexidartinib originally bound CSF1RWT with π–π stack interactions both at W550 and F797, arranged its binding pose from the allosteric pocket to ATP-binding site. In addition, the fluorine group at the ligand’s tail also formed halogen bonds with Valine position 548th hence increased binding affinity and secure the ligand in binding pocket without need for W550 π–π stack interaction. With these factors, it is not surprising that mutation W550A showed no significant impact on pexidartinib.

According to MM/GBSA results and interaction analysis in both CSF1RWT and CSF1RW550A with respect to the trans-(−)-kusunokinin or drugs, W550, among other factors, is crucial for ligand binding CSF1R. However, in order to improve CSF1R binding affinity, as well as specificity and selectivity, length extension of the ligand with polar groups, mimic to the structure of pexidartinib and imatinib, should be examined. Further study on CSF1R-inhibitor structure–activity relationships (SAR) as well as ADME profile of the modified trans-(−)-kusunokinin based CSF1R-specific targeted drugs should be performed according to the proposed guideline noted here.

Conclusion

W550 plays an important role in regulating CSF1R inhibitory state via the interaction with conserved D796 of the DFG-motif. However, replacing W550 with Alanine had no effect on the binding position of trans-(−)-kusunokinin or the CSF1R inhibitors. CSF1R conformational change upon ligand-binding which indicates the inhibitory effect of the binding ligand also unaffected by lack of W550’s aromatic sidechain. Instead, the presence of W550 is important in increasing binding affinity by forming π–π stack interaction with the aromatic structure of the inhibitor. Trans-(−)-kusunokinin bound the CSF1R inhibitor site with significantly decreased binding affinity in CSF1RW550A, compared to CSF1RWT, while the trans-(+)-kusunokinin bound differently. Apart from the binding and specificity, the study of off-target effects of the (–)-kusunokinin such as cytotoxicity and drug-likeness gave the acceptable drug-candidate possibility. As a result, to create CSF1R-specific small-molecule inhibitors based on the trans-(−)-kusunokinin structure, the benzine ring at one arm should be preserved while the length extension of the ligand with polar groups for increased CSF1R specificity and binding affinity should be considered.

Methods

Protein structure preparation

CSF1R kinase 3D X-ray crystal structures in autoinhibited state (PDB ID 2OGV and 8CGC), DFG-in conformation (PBB ID 3LCD), DFG-out conformation (PDB ID 3LCO), and complex with FDA-approved inhibitor pexidartinib (PDB ID 4R7H) were obtained as PDB files from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). The co-crystallised ligand and solvent molecules were removed using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software version 1.9.3101. All polar hydrogens were added to the CSF1R structures corresponding to the protonation state at pH 7 using AutoDock Auxillary Tool (ADT) version 1.5.6102.

Ligand preparation

The co-crystallised ligands from CSF1R kinase crystal structures were retrieved from the original PDB files to be docked as reference binding sites to compare with the tested ligand. The 3D conformers of trans-(−)-kusunokinin and trans-(+)-kusunokinin, as well as 14 pan-RTK class III inhibitors and 15 specific/dual CSF1R antagonists (name and CID listed in Table S1) were obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). SDF files were converted to PDB using the Online SMILE Translator and Structure File Generator (https://cactus.nci.nih.gov/translate/index.html). Missing polar hydrogens were added to the ligand structures and saved as PDBQT file format using AutoDock Auxillary Tool (ADT) version 1.5.6 prior to molecular docking.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed on AutoDock version 4.2.6102. All docking parameters were set based on previous studies54,103 using python shell command from MGLTools version 1.5.4104. The grid box was set on the center of the macromolecule with x–y–z grid point numbers of 126–126–126, which was the maximum grid box size to ensure the grid box covered the whole protein structure. The grid spacing was set at 0.375 Å as a default value (Fig. S5). A genetic algorithm (GA) with 50 runs and a population size of 200 was performed with default parameters. A Lamarckian genetic algorithm (4.2) was applied to predict binding conformations. The docking procedure was run 5 times for each system. Only the binding poses of the docked ligand within the same binding pocket as the reference co-crystallised CSF1R inhibitors were accepted for further investigation as described in previous study54. The lowest docking score in kcal/mol was considered the best binding pose. The Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer version 19.1105 and VMD were used to see the ligand–protein interactions and docking poses.

Alanine mutagenesis

The structure of CSF1R kinase in complex with pexidartinib (PDB ID 4R7H) was used as a CSF1R wild-type (CSF1RWT) template to generate mutated CSF1RW550A model with the FoldX106 BuildModel command. The mutated models were then optimized and folding-free energy changes upon mutation in kcal/mol were calculated using the Stability command to evaluate the protein stability upon point mutation64. All models were superimposed, and conformational changes were examined prior to the docking procedure.

After generated the mutated model, it was optimized using the Optimize command in FoldX version 5.0106 to repair any missing side chain atoms and eliminate the Vander Waals clashes upon the introduced residue substitution. The folding-free energy changes upon mutation (ΔΔG) in kcal/mol were calculated using the Stability command to evaluate the protein stability upon point mutation. The ΔΔG between − 0.75 and − 5 kcal/mol was considered to have stabilizing effects and ΔΔG of > + 1 kcal/mol was considered to have destabilizing effects on the mutated model64,107. The mutated model was superimposed to the wild-type 4R7H template using VMD to examine the conformational changes upon mutation prior to the docking procedure. The mutated model without significant conformational changes which threaten to docking failures was accepted to perform Molecular docking and MD simulations.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

The docked ligand–protein complexes served as the starting points for subsequent MD runs with the AMBER16 package108. The system preparation and minimization steps were carried out at 298 K and 1.013 Bar in an isotonic 0.15 M NaCl solution, as previously studied54. The simulation was run for 100 ns in triplicate, which equivalate to a total of 300 ns sampling time per model. We decided to perform independent 100-ns MD simulations in triplicate109,110,111 to reduce the bias from the initial structure and to ensure the ligand stays within the binding pocket, as an increasing instability of trans-(+)-kusunokinin-CSF1R complex was observed after 100 ns from the total 300 ns simulation study54.

Using the root mean square deviation (RMSD) parameter, the MD trajectory of 2000 snapshots was examined for ligand–protein stability. The last 800 snapshots were used to evaluate conformational changes caused by ligand binding using the root-mean square fluctuation (RMSF) based on the fluctuation of the amino acid α-carbon position. The amino number in this paper was referred to the amino sequence number of human CSF1R (ID 4R7H), concluded in the Table S4. To ensure the simulated system reaches the equilibrium state, the NVT ensemble temperature fluctuating, the RMSD and the radius of gyration (Rg) were computed and the deviation of the 100-ns simulation temperature, the RMSD and the Rg between the triplicated runs were calculated.

The average relative binding free energies (ΔG) in kcal/mol, as well as the total contribution energies of interacted residues, were also calculated from the triplicated last 800 snapshots using molecular mechanics/generalized Born-surface area (MM/GBSA)79. The energetics terms were briefly summarised in the previous studies54,80,81. All the MD results in triplicate, in the total of 300 ns sampling, from each system in three independent simulations were calculated with LibreOffice Calc version 5.1.6.2 and represented as mean ± SD. Ubuntu Xmgrace version 5.1.25 was used to visualise the graph. All software was operated in Ubuntu version 16.04.

Distance analysis

To determine the ligand's binding profiles to the protein, distance between the ligand center of mass and the protein center of mass was averaged by the triplicated MD system and plotted along the simulation to investigate the effect of the W550A mutation on ligand binding pocket.

The distances from the protein center to each amino acid residue were also retrieved from the last 800 snapshots and were averaged by the triplicated MD system. The conformational changes upon ligand binding and the mutation impact on this aspect were measured by comparing the differences in the average distance patterns (Δd) between ligand-free CSF1RWT and ligand-free CSF1RW550A. The Δd between the ligand-free CSF1RWT and the ligand-bound CSF1RWT (Δd1) or the Δd between the ligand-free CSF1RW550A and the ligand-bound CSF1RW500A (Δd2) were also measured to indicate the conformational changes upon ligand-binding. The Δd1 and the Δd2 were plotted together to visualize the impact of alanine mutagenesis in term of ligand-binding to protein and the differences in the Δd1 and the Δd2 (ΔΔd) were calculated to determine the effected residue. The absolute ΔΔd greater than 1.5 Å were considered effected, Fig. 8.

Concept for Distance Analysis. In the wild-type simulation, the distances from the center of structure to amino residues 1 and 2 are denoted by d1n1 and d1n2, whereas in the W550A simulation, the distances are denoted by d2n1 and d2n2. The varying distances indicated the position of the same amino acid in both wild-type and mutant structures. If d1n1 is longer than d2n1, it indicates that amino residue 1 is further from the center, vice versa. In this concept, a significant difference in distance may indicate that the amino residue is in a different position as well as conformational similarity. The protein structures were generated using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software version 1.9.3.

To indicate the inhibitory effect of tested ligand, the α-carbon distance between CSF1R Asparagine position 783rd (D783) which is the first Asparagine follows the HRDxxxN motif and Phenylalanine position 797th (F797) in the DFG motif (d1) was compared to the α-carbon distance between the conserved Glutamic acid position 633rd (E633) on the αC-helix and Phenylalanine position 797th (F797) (d2). The CSF1R state was considered DFG-out or inactive state when d1 < d2 and considered DFG-in or active state when d1 > d2. The classical DFG-out conformation cut-off at d1 < 7.2 Å and d2 > 9 Å43.

Off-target predictions

The off-target predictions were performed using Protox 3.0 (https://comptox.charite.de/protox3) for cytotoxicity profile, SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) for drug-likeness parameters, and SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) for drug-target prediction. The input for all predictions stated earlier was the compound isomeric SMILE from Pubchem database. The pubchem CIDs were summarized in the Table S1.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article or its supplementary data files. The supporting information as the zip files, include 6 tables, and 5 figures as followed: Table S1. Docked ligand name and PubChem CID. Table S2. Docking scores of all tested ligands to all tested CSF1R states. Table S3. Interacted residues of docked ligands. Table S4. Reference- and MD rearranged-residue number of the CSF1R kinase domain PDB ID 4R7H. Table S5. Different in distance from protein center to each amino acid residue (average from the last 800 snapshots from the tripicate MD systems). Table S6. Distance between ASN783 to PHE797 (d1) and GLU633 to PHE797 (d2). Figure S1. Off-target profiles of imatinib. Figure S2. Off-target profiles of pexidartinib. Figure S3. Off-target profiles of trans-(–)-kusunokinin. Figure S4. Off-target profiles of trans-(+)-kusunokinin. Figure S5. Molecular docking parameters. The off-target profile figures were generated using Protox 3.0 (comptox.charite.de/protox3) for cytotoxicity profile, SwissADME (www.swissadme.ch) for drug-likeness parameters, and SwissTargetPrediction (www.swisstargetprediction.ch) for drug-target prediction.

Abbreviations

- CSF1R:

-

Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- MD:

-

Molecular dynamics

- RTK:

-

Receptor tyrosine kinase

- TK:

-

Tyrosine kinase

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

References

Lemmon, M. A. & Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 141(7), 1117–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011 (2010).

Wang, Z. & Cole, P. A. Catalytic mechanisms and regulation of protein kinases. Methods Enzymol. 548, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397918-6.00001-X (2014).

Robinson, D. R., Wu, Y. M. & Lin, S. F. The protein tyrosine kinase family of the human genome. Oncogene. 19(49), 5548–5557. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1203957 (2000).

Drake, J. M., Lee, J. K. & Witte, O. N. Clinical targeting of mutated and wild-type protein tyrosine kinases in cancer. Mol. Cell Biol. 34(10), 1722–1732. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01592-13 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Mechanistic insights into the activation of oncogenic forms of EGF receptor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18(12), 1388–1393. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2168 (2011).

Jechlinger, M. et al. Autocrine PDGFR signaling promotes mammary cancer metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 116(6), 1561–1570. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI24652 (2006).

Weigand, M., Hantel, P., Kreienberg, R. & Waltenberger, J. Autocrine vascular endothelial growth factor signalling in breast cancer: Evidence from cell lines and primary breast cancer cultures in vitro. Angiogenesis. 8(3), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-005-9010-0 (2005).

Winkler, G. C., Barle, E. L., Galati, G. & Kluwe, W. M. Functional differentiation of cytotoxic cancer drugs and targeted cancer therapeutics. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 70(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.06.012 (2014).

Blume-Jensen, P. & Hunter, T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 411(6835), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1038/35077225 (2001).

Huang, L., Jiang, S. & Shi, Y. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors in the past 20 years (2001–2020). J. Hematol. Oncol. 13(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00977-0 (2020).

Templeton, A. J. et al. Prognostic relevance of receptor tyrosine kinase expression in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 40(9), 1048–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.08.003 (2014).

Rosnet, O. & Birnbaum, D. Hematopoietic receptors of class III receptor-type tyrosine kinases. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 4(6), 595–613 (1993).

Sherr, C. J. The colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor: Pleiotropy of signal-response coupling. Lymphokine Res. 9(4), 543–548 (1990).

Pixley, F. J. & Stanley, E. R. CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol. 14(11), 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.016 (2004).

Sapi, E. The role of CSF-1 in normal physiology of mammary gland and breast cancer: An update. Exp. Biol. Med. 229(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/153537020422900101 (2004).

Cohen, P. E., Zhu, L. & Pollard, J. W. Absence of colony stimulating factor-1 in osteopetrotic (csfmop/csfmop) mice disrupts estrous cycles and ovulation. Biol. Reprod. 56(1), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod56.1.110 (1997).

Kacinski, B. M. et al. FMS (CSF-1 receptor) and CSF-1 transcripts and protein are expressed by human breast carcinomas in vivo and in vitro. Oncogene. 6(6), 941–952 (1991).

Kluger, H. M. et al. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor expression is associated with poor outcome in breast cancer by large cohort tissue microarray analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 10(1 Pt 1), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0699-3 (2004).

Tamimi, R. M. et al. Circulating colony stimulating factor-1 and breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 68(1), 18–21. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3234 (2008).

Stanley, E. R. & Chitu, V. CSF-1 receptor signaling in myeloid cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6(6), a021857. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021857 (2014).

Novak, U. et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1-induced STAT1 and STAT3 activation is accompanied by phosphorylation of Tyk2 in macrophages and Tyk2 and JAK1 in fibroblasts. Blood. 86(8), 2948–2956 (1995).

Morandi, A., Barbetti, V., Riverso, M., Dello Sbarba, P. & Rovida, E. The colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) receptor sustains ERK1/2 activation and proliferation in breast cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 6(11), e27450. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027450 (2011).

Lin, E. Y., Nguyen, A. V., Russell, R. G. & Pollard, J. W. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J. Exp. Med. 193(6), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.193.6.727 (2001).

Aharinejad, S. et al. Elevated CSF1 serum concentration predicts poor overall survival in women with early breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 20(6), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-13-0198 (2013).

Barbetti, V. et al. Chromatin-associated CSF-1R binds to the promoter of proliferation-related genes in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 33(34), 4359–4364. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.542 (2014).

Giricz, O. et al. The RUNX1/IL-34/CSF-1R axis is an autocrinally regulated modulator of resistance to BRAF-V600E inhibition in melanoma. JCI Insight. 3(14), e120422. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.120422 (2018).

Kacinski, B. M. CSF-1 and its receptor in ovarian, endometrial and breast cancer. Ann. Med. 27(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853899509031941 (1995).

Kacinski, B. M. CSF-1 and its receptor in breast carcinomas and neoplasms of the female reproductive tract. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 46(1), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1%3c71::AID-MRD11%3e3.0.CO;2-6 (1997).

Patsialou, A. et al. Autocrine CSF1R signaling mediates switching between invasion and proliferation downstream of TGFβ in claudin-low breast tumor cells. Oncogene. 34(21), 2721–2731. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2014.226 (2015).

Patsialou, A. et al. Invasion of human breast cancer cells in vivo requires both paracrine and autocrine loops involving the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor. Cancer Res. 69(24), 9498–9506. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1868 (2009).

Koedoot, E. et al. Uncovering the signaling landscape controlling breast cancer cell migration identifies novel metastasis driver genes. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 2983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11020-3 (2019).

Scholl, S. M. et al. Circulating levels of the macrophage colony stimulating factor CSF-1 in primary and metastatic breast cancer patients: A pilot study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 39(3), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01806155 (1996).

Ma, J. H., Qin, L. & Li, X. Role of STAT3 signaling pathway in breast cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 18(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-020-0527-z (2020).

Qin, J. J., Yan, L., Zhang, J. & Zhang, W. D. STAT3 as a potential therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer: A systematic review. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1206-z (2019).

Bingle, L., Brown, N. J. & Lewis, C. E. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: Implications for new anticancer therapies. J. Pathol. 196(3), 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1027 (2002).

Mo, H. et al. Overexpression of macrophage-colony stimulating factor-1 receptor as a prognostic factor for survival in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 100(12), e25218. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000025218 (2021).

Richardsen, E., Uglehus, R. D., Johnsen, S. H. & Busund, L. T. Macrophage-colony stimulating factor (CSF1) predicts breast cancer progression and mortality. Anticancer Res. 35(2), 865–874 (2015).

Woo, H. H., László, C. F., Greco, S. & Chambers, S. K. Regulation of colony stimulating factor-1 expression and ovarian cancer cell behavior in vitro by miR-128 and miR-152. Mol. Cancer. 11, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-11-58 (2012).

Baghdadi, M. et al. High co-expression of IL-34 and M-CSF correlates with tumor progression and poor survival in lung cancers. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 418. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18796-8 (2018).

Okugawa, Y. et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1 and colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor co-expression is associated with disease progression in gastric cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 53(2), 737–749. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2018.4406 (2018).

Ide, H. et al. Expression of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor during prostate development and prostate cancer progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99(22), 14404–14409. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.222537099 (2002).

Edwards, D. K. et al. CSF1R inhibitors exhibit antitumor activity in acute myeloid leukemia by blocking paracrine signals from support cells. Blood. 133(6), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-03-838946 (2019).

Monestime, S. & Lazaridis, D. Pexidartinib (TURALIO™): The first FDA-indicated systemic treatment for tenosynovial giant cell tumor. Drugs R D. 20(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-020-00314-3 (2020).

Cannarile, M. A. et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors in cancer therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 5(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-017-0257-y (2017).

Wen, J., Wang, S., Guo, R. & Liu, D. CSF1R inhibitors are emerging immunotherapeutic drugs for cancer treatment. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 245(1), 114884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114884 (2023).

Cohen, M. H. et al. Approval summary for imatinib mesylate capsules in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 8(5), 935–942 (2002).

Wilson, E. A., Russu, W. A. & Shallal, H. M. Preliminary in vitro and in vivo investigation of a potent platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) family kinase inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 28(10), 1781–1784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.030 (2018).

Nishida, T. et al. Secondary mutations in the kinase domain of the KIT gene are predominant in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Sci. 99(4), 799–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00727.x (2008).

Mughal, T. I. & Schrieber, A. Principal long-term adverse effects of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. Biologics. 4, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S5775 (2010).

Bellora, F. et al. Imatinib and nilotinib off-target effects on human NK cells, monocytes, and M2 macrophages. J. Immunol. 199(4), 1516–1525. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1601695 (2017).

Hubbard, S. R. Structural analysis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 71(3–4), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00047-9 (1999).

Shyam Sunder, S., Sharma, U. C. & Pokharel, S. Adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: Pathophysiology, mechanisms and clinical management. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 8(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01469-6 (2023).

Rattanaburee, T., Tipmanee, V., Tedasen, A., Thongpanchang, T. & Graidist, P. Inhibition of CSF1R and AKT by (±)-kusunokinin hinders breast cancer cell proliferation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 129, 110361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110361 (2020).

Chompunud Na Ayudhya, C., Graidist, P. & Tipmanee, V. Potential stereoselective binding of trans-(±)-kusunokinin and cis-(±)-kusunokinin isomers to CSF1R. Molecules. 27(13), 4194. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134194 (2022).

Sriwiriyajan, S., Sukpondma, Y., Srisawat, T., Madla, S. & Graidist, P. (–)-Kusunokinin and piperloguminine from Piper nigrum: An alternative option to treat breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 92, 732–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.130 (2017).

Tedasen, A. et al. (–)-Kusunokinin inhibits breast cancer in N-nitrosomethylurea-induced mammary tumor rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 882, 173311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173311 (2020).

Rattanaburee, T. et al. Anticancer activity of synthetic (±)-kusunokinin and its derivative (±)-bursehernin on human cancer cell lines. Biomed. Pharmacother. 117, 109115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109115 (2019).

Mad-Adam, N., Rattanaburee, T., Tanawattanasuntorn, T. & Graidist, P. Effects of trans-(±)-kusunokinin on chemosensitive and chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 23(2), 59. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2021.13177 (2022).

Rattanaburee, T., Tanawattanasuntorn, T., Thongpanchang, T., Tipmanee, V. & Graidist, P. Trans-(−)-kusunokinin: A potential anticancer lignan compound against HER2 in breast cancer cell lines?. Molecules. 26(15), 4537. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26154537 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Phase I dose-escalation study of chiauranib, a novel angiogenic, mitotic, and chronic inflammation inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-018-0695-0 (2019).

Kitagawa, D. et al. Activity-based kinase profiling of approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Genes Cells. 18(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/gtc.12022 (2013).

Lee, K. H. et al. Discovery of BPR1R024, an orally active and selective CSF1R inhibitor that exhibits antitumor and immunomodulatory activity in a murine colon tumor model. J. Med. Chem. 64(19), 14477–14497. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01006 (2021).

Vijayan, R. S. et al. Conformational analysis of the DFG-out kinase motif and biochemical profiling of structurally validated type II inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 58(1), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm501603h (2015).

Khan, S. & Vihinen, M. Performance of protein stability predictors. Hum. Mutat. 31(6), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.21242 (2010).

Ramírez, D. & Caballero, J. Is it reliable to take the molecular docking top scoring position as the best solution without considering available structural data?. Molecules. 23(5), 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051038 (2018).

Cosconati, S. et al. Virtual screening with autodock: Theory and practice. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 5(6), 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1517/17460441.2010.484460 (2010).

Sharma, J., Bhardwaj, V. K., Das, P. & Purohit, R. Identification of naturally originated molecules as γ-aminobutyric acid receptor antagonist. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39(3), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2020.1720818 (2021).

Kumar, S., Sinha, K., Sharma, R., Purohit, R. & Padwad, Y. Phloretin and phloridzin improve insulin sensitivity and enhance glucose uptake by subverting PPARγ/Cdk5 interaction in differentiated adipocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 383(1), 111480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.06.025 (2019).

Kumar, A., Rajendran, V., Sethumadhavan, R. & Purohit, R. Molecular dynamic simulation reveals damaging impact of RAC1 F28L mutation in the switch I region. PLoS ONE. 8(10), e77453. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077453 (2013).

Singh, R., Bhardwaj, V. K., Sharma, J., Das, P. & Purohit, R. Identification of selective cyclin-dependent kinase 2 inhibitor from the library of pyrrolone-fused benzosuberene compounds: An in silico exploration. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 40(17), 7693–7701. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2021.1900918 (2022).

Kumar, A., Rajendran, V., Sethumadhavan, R. & Purohit, R. Evidence of colorectal cancer-associated mutation in MCAK: A computational report. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 67(3), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-013-9572-1 (2013).

Kumar, A. et al. Computational SNP analysis: Current approaches and future prospects. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 68(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-013-9705-6 (2014).

Merski, M., Skrzeczkowski, J., Roth, J. K. & Górna, M. W. A geometric definition of short to medium range hydrogen-mediated interactions in proteins. Molecules. 25(22), 5326. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25225326 (2020).

Bossemeyer, D., Engh, R. A., Kinzel, V., Ponstingl, H. & Huber, R. Phosphotransferase and substrate binding mechanism of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit from porcine heart as deduced from the 2.0 A structure of the complex with Mn2+ adenylyl imidodiphosphate and inhibitor peptide PKI(5–24). EMBO J. 12(3), 849–859. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05725.x (1993).

Knighton, D. R. et al. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science. 253(5018), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1862342 (1991).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.235 (2000).

Schindler, T. et al. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 289(5486), 1938–1942. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5486.1938 (2000).

Nagar, B. et al. Crystal structures of the kinase domain of c-Abl in complex with the small molecule inhibitors PD173955 and imatinib (STI-571). Cancer Res. 62(15), 4236–4243 (2002).

Genheden, S. & Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 10(5), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936 (2015).

Chen, J. et al. Revealing origin of decrease in potency of darunavir and amprenavir against HIV-2 relative to HIV-1 protease by molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 4, 6872. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06872 (2014).

Chen, J., Zeng, Q., Wang, W., Sun, H. & Hu, G. Decoding the identification mechanism of an SAM-III riboswitch on ligands through multiple independent gaussian-accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62(23), 6118–6132. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c00961 (2022).

Da Silva Figueiredo, P. et al. Differential effects of CSF-1R D802V and KIT D816V homologous mutations on receptor tertiary structure and allosteric communication. PLoS ONE. 9(5), e97519. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097519 (2014).

Tap, W. D. et al. Structure-guided blockade of CSF1R kinase in tenosynovial giant-cell tumor. N. Engl. J. Med. 373(5), 428–437. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411366 (2015).

Caldwell, T. M. et al. Discovery of vimseltinib (DCC-3014), a highly selective CSF1R switch-control kinase inhibitor, in clinical development for the treatment of tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT). Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 74, 128928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2022.128928 (2022).

El-Gamal, M. I. et al. Recent advances of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) kinase and its inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 61(13), 5450–5466. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00873 (2018).

Azhar, Z., Grose, R. P., Raza, A. & Raza, Z. In silico targeting of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor: Delineating immunotherapy in cancer. Explor. Target Antitumor. Ther. 4(4), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.37349/etat.2023.00164 (2023).

Drewry, D. H. et al. Identification of pyrimidine-based lead compounds for understudied kinases implicated in driving neurodegeneration. J. Med. Chem. 65(2), 1313–1328. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00440 (2022).

Burley, S. K. & Petsko, G. A. Aromatic-aromatic interaction: A mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science. 229(4708), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3892686 (1985).

Meyer, E. A., Castellano, R. K. & Diederich, F. Interactions with aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42(11), 1210–1250. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200390319 (2003) (Erratum in: Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003 Sep 15;42(35):4120).

Daeffler, K. N., Lester, H. A. & Dougherty, D. A. Functionally important aromatic-aromatic and sulfur-π interactions in the D2 dopamine receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134(36), 14890–14896. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja304560x (2012).

Shao, J. et al. The role of tryptophan in π interactions in proteins: An experimental approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144(30), 13815–13822. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c04986 (2022).

Dimitrijević, B. P., Borozanb, S. Z. & Stojanović, S. D. π–π and cation–π interactions in protein–porphyrin complex crystal structures. RSC Adv. 2(33), 12963–12972. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2RA21937A (2012).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S. et al. A structure-based computational workflow to predict liability and binding modes of small molecules to hERG. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72889-5 (2020).

Tanawattanasuntorn, T. et al. (-)-kusunokinin as a potential aldose reductase inhibitor: Equivalency observed via AKR1B1 dynamics simulation. ACS Omega. 6(1), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c05102 (2020).

Aarhus, T. I. et al. A highly selective purine-based inhibitor of CSF1R potently inhibits osteoclast differentiation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 255, 115344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115344 (2023).

Liang, X. et al. Discovery of Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives as potent and selective colony stimulating factor 1 receptor kinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 243, 114782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114782 (2022).

Aarhus, T. I. et al. Synthesis and development of highly selective pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine CSF1R inhibitors targeting the autoinhibited form. J. Med. Chem. 66(10), 6959–6980. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00428 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Anti-estrogenic activity of lignans from Acanthopanax chiisanensis root. Arch. Pharm. Res. 28(2), 186–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02977713 (2005).

Möbitz, H. The ABC of protein kinase conformations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1854(10), 1555–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.03.009 (2015).

Schubert, C. et al. Crystal structure of the tyrosine kinase domain of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (cFMS) in complex with two inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 282(6), 4094–4101. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M608183200 (2007).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 (1996).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30(16), 2785–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21256 (2009).

Rattanaburee, T., Chompunud Na Ayudhya, C., Thongpanchang, T., Tipmanee, V. & Graidist, P. Trans-(±)-TTPG-B attenuates cell cycle progression and inhibits cell proliferation on cholangiocarcinoma cells. Molecules. 28(21), 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28217342 (2023).

Sanner, M. F. Python: A programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph Model. 17(1), 57–61 (1999).

BIOVIA. Discovery Studio Modeling Environment, Release 2017 (Dassault Systèmes, 2016).

Schymkowitz, J. et al. The FoldX web server: An online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W382–W388. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki387 (2005).

Broom, A., Jacobi, Z., Trainor, K. & Meiering, E. M. Computational tools help improve protein stability but with a solubility tradeoff. J. Biol. Chem. 292(35), 14349–14361. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M117.784165 (2017).

Case, D. A. et al. AMBER 2020 (University of California, 2020).

Condic-Jurkic, K., Subramanian, N., Mark, A. E. & O’Mara, M. L. The reliability of molecular dynamics simulations of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein in a membrane environment. PLoS ONE. 13(1), e0191882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191882 (2018).

Salimi, A., Lim, J. H., Jang, J. H. & Lee, J. Y. The use of machine learning modeling, virtual screening, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations to identify potential VEGFR2 kinase inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 18825. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22992-6 (2022).

Saetang, J. et al. Computational discovery of binding mode of anti-TRBC1 antibody and predicted key amino acids of TRBC1. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1760. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05742-6 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Graduate Scholarship from Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University (Grant No. 63-006), and Fundamental Fund 2566 (FF66) from Thailand Science Research and Innovation, Thailand (Grant No. MED6601223S). The financial support was also acknowledged by Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand (Grant No. MR-PSU: 66-38-23-115). The research was reviewed by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University under a reference of REC.65-024-4-2 as an exemption category.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G. and V.T. for conceptualization. V.T. provided crucial software. C.C. and V.T. for data curation and formal analysis. P.G. for funding acquisition. P.G. and V.T. for project administration. P.G. and V.T. provided resources. P.G. and V.T. for supervision. C.C. and V.T. for validation and visualization. C.C. and V.T. writing–original draft preparation. C.C., P.G. and V.T. writing–review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chompunud Na Ayudhya, C., Graidist, P. & Tipmanee, V. Role of CSF1R 550th-tryptophan in kusunokinin and CSF1R inhibitor binding and ligand-induced structural effect. Sci Rep 14, 12531 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63505-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63505-x