Abstract

Betula utilis exhibits intriguing characteristics and interactions with its environment and has specific adaptations that enable it to thrive in various water conditions. Drought has a prominent role in influencing the growth and development of vegetation, while temperature serves as a crucial determinant of species distribution in high-altitude environments. The investigation was centered on the eco-physiological dimension of B. utilis in areas near the treeline. Across different seasons, sites, and years, the most negative pre-dawn twig water potentials (ΨPD) and mid-day twig water potentials (ΨMD) were − 0.81 and − 1.24 MPa, respectively. The highest seasonal change (ΔΨ) in twig water potential (Ψtwig) was in the post-monsoon season. Osmotic potential at full turgor (Ψπ100) declined by − 0.66 MPa and osmotic potential at zero turgor (Ψπ0) declined by − 1.07 MPa. The highest leaf conductance (gw) of 380.26 mmol m−2 s−1 was measured in the afternoon. During the initiation of flowering, ΨPD of the twig was − 0.72 MPa and gradually rose to − 0.17 MPa by the end of the flowering period. This study provides key insight into the Ψ dynamics, leaf conductance, and phenology of B. utilis, highlighting its adaptation to changing environmental conditions and the need for effective management strategies to ensure the resilience and conservation of this Critically Endangered species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In mountainous regions, as elevations increase a rapid change in environmental factors such as temperature decline rapidly, and a noticeable change in vegetation is visible. Trees may take on deformed, bush-like forms. This transition zone between the contiguous subalpine forest and open alpine tundra is commonly known as treeline ecotone. The Himalaya boasts the highest and most diverse treelines globally, making it an ideal region to study climate change’s imprints1. In this ecologically significant area, the treeline zone experiences fluctuations in vegetation due to long-term climatic changes. The complex interplay of geographical factors, topography, microclimatic conditions, herbivory, and human influence shapes the structure, composition, and regeneration patterns of timberline vegetation2,3.

B. utilis D. Don (Birch), is a dominant species in the treeline zone and considered the climax forest for the Himalayas. The Betula forest has an important role in the ecosystem, making it an ecologically and reasonably keystone species4. The species functions as a transitional zone between sub-alpine and alpine regions in the Himalayan5. The species under consideration has a wide range, including both frequent and unusual occurrences. Its habitat spans elevations ranging from 2400 to 4300 m above sea level6. The aforementioned region constitutes the highest segment of the natural treeline zone, exhibiting a range of around 3300 to 3800 m. The genus Betula occupies a broad longitudinal range in the Northern Hemisphere from sub-tropics to arctic, distributed in various habitats like bogs, highlands, tundra, and forests6. Taxonomically, the genus Betula is polyploidy, hybridization, introgression, morphological convergences, and specimen misidentifications are the main reasons for the misclassification and disagreement in the taxonomy of the genus Betula6. Nevertheless, it encounters obstacles, namely attributable to the phenomenon of climate change and the concurrent increase in temperatures. According to existing research, temperature is a significant factor in influencing the geographic spread of B. utilis in the Hindukush Himalaya region. In light of the phenomenon of climate change, the studied species have been shown to exhibit a notable expansion in their geographical distribution towards elevated altitudes7. The spread of birch is influenced by precipitation and temperature, particularly soil moisture and snow cover during the growth season8.

The population of B. utilis encounters difficulties inside the treeline zone as a result of its sluggish regeneration in comparison to other species inhabiting the treeline9. The species also faces competition from a diverse range of alpine and sub-alpine environments, resulting in a decrease in its population size10, with estimates ranging from 50 to 85% in some areas of the Hindukush and the Himalayas11. The loss of the species has been exacerbated by human activities, leading to its categorization as Critically Endangered in the Indian Himalayan Region12. The management and restoration efforts of high mountain forests are further complicated by the lack of comprehensive understanding of the community features and ecology of these ecosystems13. The presence and accessibility of water, both within the soil and in the atmosphere, are significant factors that influence the distribution and growth patterns of plant species10. Ensuring sufficient hydration and turgidity is crucial for the proper functioning and growth of plants. The equilibrium is determined by the amount of water absorption relative to water loss14. In response to water stress, plants have evolved several mechanisms to enhance water absorption or minimize water transpiration15. When faced with varying moisture levels, plants of the same species exhibit considerable variation in size and other morphological and physiological characteristics16. This demonstrates their ability to adapt to different environmental conditions and optimize their growth in response to water availability. Species-specific characteristics such as rooting depth, leaf phenology, wood morphology, xylem characteristics, and growth rate, all contribute to variability in different environmental conditions.

One of the critical climatic events affecting natural ecosystems, especially treeline areas in the Himalayan region, is drought17. Trees that grow in the treeline region endure harsh environmental conditions; thus, they have developed unique adaptations to optimize their water use efficiency. With increasing water stress, below a threshold value of ΨPD close to − 1.1 MPa, B. utilis seedlings exhibit a severe reduction in stomatal conductance and an increase in leaf shedding18. To facilitate the process of leaf growth, it is crucial to regulate water loss, alter osmotic potential, maintain tissue flexibility, and ensure the continuity of xylem conductance19. Plants are capable of maintaining turgor pressure and facilitating cell growth and high-water uptake even when faced with low Ψ using diminishing osmotic potential (Ψπ). European white birch (B. pendula) often had a ΨMD near the turgor loss point, even under well-watered conditions, and that stomatal conductance to water vapour (gs), decreased in response to mild soil water deficits20, while another observation shows that its maintained fairly uniform ΨMD, slightly above their Ψ at the turgor loss point (Ψt/p), despite variation in vapour pressure deficit and ΨPD21. The regulation of water uptake is crucial for water relations, as species at the treeline exhibit lower stomatal conductance in response to limited water availability, thereby reducing water loss. Transpiration, driven by the humidity gradient between leaves and the atmosphere, can be impacted by temperature effects in the winter season, leading to increased transpiration due to overheating22. The B. utilis species with low osmotic potential at full hydration (Ψπ, sat) values were better able to maintain turgor with decreasing Ψ, and they maintained higher gs and developed lower ΨMD under mild water stress than species with high Ψπ, sat21.

The water relations of Himalayan treeline species are of considerable importance in their phenological phases, since these trees have developed adaptations in their phenological patterns to align their development and reproductive processes with the presence of water and suitable climatic conditions. Several researches work that has been carried out in the past have focused on vegetation structure and composition23,24, climate change25,26, floristic diversity27,28, ethnobotanical surveys29,30, biomass productivity and carbon storage27,31, vegetation dynamics concerning human disturbances and edaphic conditions32,33,34,35, criteria and indicator for assessing threat timberline species5 in the treeline region. In particular, the eco-physiological aspects related to western Himalayan treeline species, especially the effect of soil and tree water relations on the vegetative and reproductive phase of the plant in the treeline environment remain poorly investigated36,37. It is apparent that there still exist several gaps in our understanding of tree water relations and its effect on some keystone treeline species. Despite B. utilis being an important tree in the treeline environment, only limited research has explored its eco-physiological aspects, particularly regarding water potential, leaf conductance, and phenology in the Indian Himalayan treeline habitat. Understanding these parameters is essential for comprehending drought resistance, and phenological activities of the species. In this study, we hypothesize that B. utilis trees exhibit adaptive mechanisms in response to variations in water potential, leaf conductance, and phenology. Specifically, we expect that B. utilis demonstrates significant adjustments in these eco-physiological parameters to cope with drought conditions typical of the treeline environment. The objective of this research is to address the existing gaps in knowledge and provide novel perspectives on the water relations and stress tolerance of B. utilis in the treeline regions of the western Himalaya, India.

Material and methods

Study sites

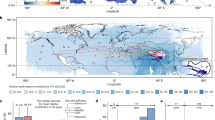

The study was conducted at three treeline locations, namely Aali, Bedni, and Tungnath, situated at coordinates 30° 11′ 02′′ N and 79° 39′ 36′′ E. These sites are located at elevations ranging from 3145 to 3467 m asl in the western Indian Himalayan region (Table 1, Fig. 1). The study locations are located in the sub-alpine and alpine zones. The soil in these regions has a characteristic brown hue and possesses a sandy loam texture, characterized by a high concentration of sand and silt particles, and exhibits acidity, as indicated by pH values ranging from 4.0 to 5.038. The climate of the research region is impacted by the monsoon, which is characterized by extended periods of harsh winters and brief periods of mild summers. The mean monthly minimum temperature varied between − 6.02 ± 0.23 and 10.36 ± 0.43 °C, the mean monthly maximum temperature varied between 3.08 ± 0.76 and 13.71 ± 1.03 °C and the total monthly precipitation was 13.0 ± 1.16 and 541.0 ± 4.37 mm during 2017–2020 at Tungnath treeline site69 (Fig. 2). The treeline in these places is mostly composed of Abies spectabilis, B. utilis, Quercus semecarpifolia, Rhododendron arboreum, and Rhododendron campanulatum, all of which were consistently detected throughout all the sites examined.

The mean monthly data of temperature and precipitation at Tungnath study site during 2017–2020. (Source: Joshi et al.69).

Measurements

In each research site, a designated area of 100 × 100 m was demarcated. Within this area, a total of twenty-five trees were randomly selected as representatives. These trees exhibited various circumferences at breast level ranging from 60 to 90 cm. All measurements were conducted only within the boundaries of this designated area36. The measurement of density was conducted by using 10 × 10 m quadrats to assess the distribution of trees (Fig. 3). Soil moisture levels (Sm) were assessed at three different depths. The twig water potential, leaf conductance, and Ψtwig components were quantified for a sample of ten marked trees. Additionally, phenological observations were recorded for a separate sample of twenty-five representative trees. A comprehensive set of 48 samples was measured at regular intervals spanning from 2017 to 2019 at the designated research locations. The study was carried out over two years spread areas four seasons (pre-monsoon, monsoon, post-monsoon, and winter) in each year. The research period included the collection of seasonal data categorized as pre-monsoon (March–May), monsoon (June–September), post-monsoon (October–November), and winter (December–February). These measurements were obtained to observe the fluctuations in the examined parameters.

Soil moisture

To estimate soil moisture, a thorough soil sampling approach was employed, focusing on three distinct depths: the upper layer (0–15 cm), the middle layer (15–30 cm), and the lower layer (30–45 cm) at seasonally. This was done at five representative locations within each site, utilizing a stainless-steel soil corer manufactured by Vienna Scientific Instruments in Vienna, Austria. In the field, a quantity of soil weighing, fifty grams was measured using a battery-operated digital weighing balance. The soil samples were subjected to a drying process at a temperature of 100 °C until a consistent weight was achieved39.

Water potential

The Ψ of B. utilis tree twigs was assessed using a Pressure chamber (PMS Instrument Co. model 1000, range 70 bars) at two specific time points: pre-dawn (ΨPD) from 5:30–6:30 h and mid-day (ΨMD) from 13:30–14:30 h. These measurements were conducted on previously marked individual trees at regular intervals throughout the seasons36,37,40. Numerous scholars have engaged in comprehensive discussions on the hypothetical and useful dimensions of this approach41,42,43. The estimation of Ψtwig was conducted by collecting samples from a vertical distance of 2–3 m. These samples were roughly 15 cm in length and had a diameter of 1–2 mm. The severed portion of the twigs was introduced through a perforated rubber stopper, with about 1.0 cm of the twigs extending beyond the stopper. Subsequently, the chamber valve was unsealed to facilitate the ingress of gas into the chamber, while concurrently modifying the pace of pressure escalation. Subsequently, the lid was affixed onto the chamber and securely fastened by twisting it. The chamber valve was activated, and further adjustments were made to the rate control and control needle valve to achieve a controlled increase in pressure inside the chamber, ranging from 0.05 to 0.25 bars per second. The N2 gas was externally pressurized until a pronounced bubbling of water was detected at the severed end of the twig. The pressure expressed in Bars/MPa is often referred to as Balance Pressure (BP), where a negative BP is interpreted as the water potential of a tree (Ψ = − BP)37,40,43.

Water potential components

To demonstrate a correlation between the constituents of Ψ and relative water content (RWC%), Pressure–Volume (PV) curves were generated by the use of a Pressure chamber. The PV curves were generated using the bench drying process. To generate PV curves, a total of 20 twigs were procured from ten distinct trees at the designated study location. These twigs were thereafter stored inside an insulated container for preservation purposes. The specimens were conveyed to the laboratory and afterwards re-sectioned at the severed extremity (4–5 cm) while submerged in water. They were then left undisturbed overnight to regain their saturation. The techniques used in this study to calculate Ψπ100, Ψπ0, and RWC% at the turgor loss point (RWCz) from the PV curves42. The investigation included the computation of osmotic adjustment, namely the decrease in Ψπ, for each of the various seasons.

Leaf conductance

B. utilis is a deciduous tree species and remains leafless between October to April. Thus, the leaf conductance rate of B. utilis was measured only for pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons. AP4 leaf porometer (“Delta-T Devices”) was used for measurements of leaf conductance rate seasonally on previously marked trees. The data on conductance were gathered during two time periods: in the forenoon (gwAM) from 10:30 to 11:30 h, and in the afternoon (gwPM) from 13:30 to 14:30 h. The measurements were taken on the sunny side of five individual leaves. The measurement of conductance rate was conducted on leaves of trees that had been permanently tagged, and from which twigs had been collected for water relation research37.

Phenological observation

A phenological study was conducted to observe five phenophases in B. utilis: leafing, flowering, fruiting, seed fall, and leaf fall. Twenty-five individual trees were randomly selected and marked at the studied treeline sites for phenological observations. During the low activity period, observations were made fortnightly, while during the peak activity period, observations were conducted weekly. Each selected tree was monitored, and the presence or absence of specific phenological phases was observed and recorded44. To consider an event as active, it had to be present and observed in at least 20% of observed tree crowns; otherwise, the events were recorded as absent45. The assessment of the crown was conducted through direct observation from a terrestrial vantage point. A phenophase was just launched if it was active and seen in 5–10% of the individuals46. Furthermore, the species was considered to stay in that phenophase as long as it was represented by at least 5–10% of the individuals. In addition, ΨPD of twigs measurements were taken during each phenological event and correlated with water status parameters of the trees38,47. This allowed for an assessment of the relationship between the ΨPD and the overall water status of the trees during different phenological stages.

Statistical analysis

The data collected were subjected to analysis using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test at significance levels of 95% and 99%. The statistical analyses in this research were performed using the software SPSS version 2016 (https://www.ibm.com/spss). The variables under investigation in the analysis of variance (ANOVA) included sites, seasons, and years, along with their respective interaction. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to evaluate the strength of the relationship between variables.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The plant sample/specimen was collected from the High-Altitude region of western Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India for research purposes and permission was obtained from the Department of Forestry and Environmental Science, Kumaun University, India. All the images in the manuscript are original and generated by the author hence no need to get permission from a third party. The research conducted from 2017-2019 strictly adhered to local and national guidelines, showcasing a commitment to ethical standards. The team diligently followed all prescribed regulations, ensuring the study’s integrity.

Results

Soil moisture

The variability of soil moisture (Sm) over different depths was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05, F = 23.96**). The Sm values exhibited variation across all study locations and seasons, ranging from 32.17 ± 0.32% to 77.22 ± 2.21% in year1 (Yr1), and from 31.56 ± 2.72% to 75.93 ± 3.19% in year2 (Yr2). The highest Sm was at a depth of 0–15 cm during the monsoon season and the minimum at a depth of 30–45 cm during the pre-monsoon season (Fig. 4). The statistical study using analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically significant differences in Sm levels across different places, seasons, and years (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Water potential

The ΨPD of B. utilis tree twigs varied between − 0.12 ± 0.07 and − 0.72 ± 0.11 MPa in Yr1 and − 0.13 ± 0.02 and − 0.81 ± 0.09 MPa in Yr2 and ΨMD was − 0.23 ± 0.04 and − 1.12 ± 0.08 MPa in Yr1 and − 0.17 ± 0.04 and − 1.24 ± 0.11 MPa in Yr2 across all the seasons and sites. Across the years the ΨPD and ΨMD of twigs were least negative during monsoon season while most negative during pre-monsoon and post-monsoon (ΨMD-Yr2) season (Fig. 5). Both pre-dawn and midday water potential of twigs showed variations across the sites, seasons and years (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Seasonal change

The average seasonal variations (ΔΨ = ΨMD − ΨPD) in the water potential of twigs were found to be 0.10 ± 0.03 and 0.50 ± 0.11 MPa in Yr1, and 0.04 ± 0.01 and 0.69 ± 0.04 MPa in Yr2, including all seasons and locations. The fluctuations in ΔΨ of twigs exhibited the least magnitude during the monsoon season, while reaching their highest levels during the post-monsoon season for both years (Fig. 6). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in the seasonal fluctuations of twigs water potential across different years, places, and seasons (Table 2).

Tree water potential components

In B. utilis tree twigs, the Ψπ100 exhibited a range of values, with − 0.94 ± 0.02 and − 1.51 ± 0.07 MPa in Yr1, and − 0.94 ± 0.01 and − 1.60 ± 0.02 MPa in Yr2. The initial Ψπ0 showed values of − 1.43 ± 0.05 and − 2.50 ± 0.10 MPa in Yr1, and − 1.45 ± 0.05 and − 2.39 ± 0.06 MPa in Yr2, across all seasons and locations. The negative values of Ψπ100 and Ψπ0 exhibited a notable decrease during the monsoon season compared to the pre-monsoon season in both years (Fig. 7). The decrease in Ψπ100 and Ψπ0 occurred throughout the monsoon (July–August) to pre-monsoon (April–May) period in both the years. The decline in Ψπ100 and Ψπ0 were − 0.57 and − 1.07 MPa in Yr1, and − 0.66 and − 0.94 MPa in Yr2 (Fig. 7). The pressure potential (Ψp) at maximum turgor of B. utilis tree twigs was measured to be 0.73 ± 0.01 and 1.86 ± 0.04 MPa in Yr1, and 0.74 ± 0.00 and 1.89 ± 0.02 MPa in Yr2, including all seasons and locations. The variable Ψ exhibited its peak value during the winter season, but its minimum value was seen during the monsoon season for both years (Fig. 7). The RWC% exhibited a range of values, specifically ranging from 78.28 ± 0.98% to 88.76 ± 0.39% in Yr1, and from 77.46 ± 1.18% to 89.37 ± 0.32% in Yr2, across all seasons and sites. The highest RWC% was observed during the winter season, followed by the monsoon season in Yr1. In Yr2, the patterns of RWC% were found to be contrary to those observed in Yr1 (Fig. 7). The analysis of variance revealed significant variation (p < 0.05) in the Ψπ100, Ψπ0, pressure potential at full turgor (Ψp100), and RWC% measurements across different seasons and sites (Table 2). Sites and seasons interaction also show significant variation (p < 0.05), while all the other interactions were not significant (Table 2).

Leaf conductance

The leaf conductance rates of B. utilis trees were measured from pre-monsoon to monsoon seasons. The gwAM ranged from 202.20 ± 5.42 to 305.76 ± 4.21 mmol m−2 s−1 in Yr1, it was minimum in monsoon season and maximum in pre-monsoon season. In Yr2 gwAM varied between 142.76 ± 2.51 to 334.60 ± 5.24 mmol m−2 s−1 it was minimum in pre-monsoon season and maximum in monsoon season. The gwPM was 100.62 ± 2.58 to 249.40 ± 1.89 mmol m−2 s−1 in Yr1 and 133.32 ± 3.14 to 380.26 ± 6.52 mmol m−2 s−1 in Yr2. The gwPM was minimum in monsoon season and maximum in pre-monsoon season across the years (Fig. 8). Statistical analysis using ANOVA indicated that the gwAM of B. utilis varied with sites and years (p < 0.05), while gwPM varied with sites, years and seasons (p < 0.05). All the interactions of forenoon and afternoon leaf conductance also varied (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Phenological observation

The leafing in B. utilis trees started in the first week of May and was completed by the second week of July. The commencement of flowering was from the third week of May and completed by the third week of July. The initiation of the catkin appearance was in the second week of August and completed by the second week of October. The seed fall was between the third week of September and the third week of November. The onset of leaf fall occurred in the fourth week of September, and the process was completed by the first week of November. The longevity of studied phenophases i.e., leafing, flowering, fruiting (catkin), seed fall and leaf fall was 70–80 days, 60–70 days, 55–65 days, 55–70 days and 40–50 days respectively (Fig. 9).

Relationship between Phenological Events and ΨPD of B. utilis

The pre-dawn water potential of tree twigs generally remained above − 0.77 ± 0.21 MPa across all the phenological activities in B. utilis. The ΨPD of twigs during the initiation of leafing in the pre-monsoon season was generally high as the leaf matured the ΨPD of twigs declined up to June and then increased in July during the monsoon season. The ΨPD of twigs was − 0.72 ± 0.13 MPa during the initiation of flowering and gradually rose − 0.17 ± 0.01 MPa at the end of the flowering season. The ΨPD of twigs was maximum during the commencement of catkin in monsoon season and as the catkin matured in post-monsoon season the ΨPD of twigs continuously declined. The ΨPD of twigs during the initiation of seed fall and leaf fall in post-monsoon and winter seasons was generally high and ranged between − 0.39 ± 0.05 and − 0.42 ± 0.10 MPa (Fig. 9).

Discussion

B. utilis are adapted to cooler climates, and prolonged heat stress can negatively impact their health. Increased temperatures can lead to physiological stress, reduced photosynthesis rates, and increased water demand, potentially leading to decreased growth and increased susceptibility to pests and diseases. The research locations are located in the peripheral regions of the Himalayas and are directly influenced by the monsoonal climate. Various elements, including terrain, soil and air temperature, soil moisture, precipitation, nutrients, snow, wind regimes, and anthropogenic pressure48, can influence tree eco-physiology. However, it is important to note that the treeline represents a climatically sensitive zone that may significantly impact tree eco-physiology owing to the presence of harsh conditions49. Soil moisture is of essential significance to numerous processes in plant life, generally, precipitation and soil moisture increase with increasing altitude, whereas air temperature decreases with increasing altitude50. In the present study, the soil moisture content varied between 31.56 and 77.22% across all the seasons throughout the study period, multiple factors, including site-specific characteristics, seasonal variations, and interannual climatic fluctuations, contribute to differences in soil moisture37. After the monsoon season, soil moisture dramatically drops from October to April during a period of very low precipitation, resulting in soil moisture deficits in the pre-monsoon season when the growing season starts51. Warming-induced higher evapotranspiration and soil moisture deficits during dry spring months adversely affect tree growth at Himalayan treelines as well as seedling/sapling density52. Moisture supply in the pre-monsoon season might become an effective control of future Himalayan treeline dynamics53,54,55.

The tree’s water relations involve a balance between water uptake through its roots and water loss through transpiration from its leaves. The root system of B. utilis is relatively shallow, allowing it to access water from the upper layers of the soil. The tree’s thin, papery bark and large leaves contribute to higher rates of transpiration, which can increase water demand during dry periods. However, it can also close its stomata (leaf pores) to reduce water loss and withstand drought conditions. In the present study, the ΨPD of twigs were − 0.12 to − 0.81 MPa and ΨMD were − 0.17 to − 1.24 MPa. The difference in pre-dawn and midday twig water potential was the least negative during the monsoon season, while the most negative during the pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons. The difference between ΨPD and ΨMD is related to how plants regulate their water status in response to soil water content. The midday water potential better reflects the maximum water stress to which plants are subjected. Previous studies on treeline species from various regions worldwide have reported critically low levels of Ψ below − 2.0 MPa, which could adversely impact normal plant functioning, during the growing season56. Nevertheless, treeline species may have challenges with water availability in the winter season when the soil is frozen, impeding the absorption of water required for the development of leaves and possibly resulting in dehydration throughout winter for young individuals22,57. These findings suggest that the monsoon season, characterized by higher precipitation, contributes to improved Ψtwigs, while the pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons, with lower rainfall and higher evaporative demands, lead to more negative Ψ values36. A significant variation was observed in twigs ΨPD and ΨMD, soil moisture, and other climatic factors that are responsible for these variations36,37,39,40 but no significant variation were observed in twigs ΨPD and ΨMD within the study sites. The complex interactions between these factors emphasize the importance of considering multiple drivers in assessing the water status of B. utilis.

To comprehensively assess the water condition of a tree, monitoring its daily fluctuations is a crucial methodology. During the investigation, distinct variations ranging from 0.40 to 0.65 MPa were identified in the seasonal fluctuation patterns of B. utilis. The values of ΔΨ ranged from 0.70 to 0.80 MPa and from 1.07 to 1.22 MPa for Himalayan treeline species, including B. utilis36. The seasonal variations in Ψtwig, occurring both diurnally and within a single day at various time points, are impacted by a confluence of environmental factors and plant physiological mechanisms37. There is a strong correlation between high ΔΨ and many key physiological processes in plants, including high transpiration rate, greater negative twig Ψ, and a high rate of photosynthesis. The highest twig ΨPD and ΔΨ were observed in the monsoon season and lowest in the pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons. The leaves of treeline species reached full expansion only during the monsoon season and achieved their maximum leaf mass, resulting in relatively low physiological activities during the pre-monsoon period36. Treeline tree species typically inhabit open habitats with intermittent exposure to sunlight during the monsoon season58. These results of ΔΨ suggest that the monsoon season, characterized by more stable and favourable water availability, contributes to smaller seasonal fluctuations in water potential.

Osmotic adjustment serves as a useful adaptation employed by trees to combat drought, as it aids in maintaining turgor pressure during dry periods and enhances their competitive ability36. Osmotic adjustment is typically quantified by measuring the decline in Ψπ throughout a drought period, which is calculated as the difference between the initial value at the start of the drought and the peak value during the drought58. The phenomenon of Ψπ reduction has been well reported in the literature as an adaptive response to the stressors of drought and salinity59. The species of trees analyzed in the study showed variability in the extent of osmotic decrease under conditions of both zero and full turgor36. In B. utilis trees a significant variation in the Ψπ, reflects changes in solute concentrations and the tree’s ability to maintain turgor pressure under different conditions. The study also shows a decline in Ψπ100 and Ψπ0 from the monsoon season to the pre-monsoon season, with a mean decline of − 0.61 and − 1.0 MPa. The present reported values were comparable to earlier reported values − 0.94 to − 1.40 MPa (Ψπ100) and − 1.43 to − 1.78 MPa (Ψπ0) for B. nigra, B. papyrifera, B. pendula, B. platyphylla and B. populifolia21 and B. utilis36,58. This decline likely reflects increased water stress and water limitation during the shift from the wetter monsoon season to the drier pre-monsoon season. The significant decline in Ψπ observed during mild drought conditions serves to ensure the availability of soil water necessary for sustaining photosynthesis60. The study demonstrates that the range of Ψp from 0.73 to 1.89 MPa. The results indicate that Ψp was highest during the winter season and lowest during the monsoon season for both years. This pattern indicates that the tree undergoes an elevation in turgor pressure and cell expansion during the winter season, when water availability is comparatively greater. Species that use deep root systems or efficient water transport mechanisms to evade dry conditions often exhibit lower levels of osmotic adjustment compared to shallow-rooted trees61. The RWCz is a method used to evaluate a plant’s capacity to maintain turgor pressure under decreasing Ψ. The RWC% of B. utilis trees shows variations between 78.28 to 89.37%. These findings indicate variations in the water-holding capacity of the tree, which could be influenced by water availability, evaporative demand, and seasonal dynamics.

In the Himalayan area, the levels of leaf conductance in various tree species might fluctuate due to fluctuations in temperature and humidity36, which are influenced by altitude and seasons. In the species B. utilis, the gwAM exhibits a range of 142.76 to 334.60 mmol m−2 s−1. These indicate variations in the gwAM rates of B. utilis, with different seasons exerting an influence on the tree’s water loss through transpiration. Similarly, the gwPM ranges from 100.62 to 380.26 mmol m−2 s−1. In the present study, gw values were comparable with earlier reported values of 102.8 to 470.19 mmol m−2 s−1 for B. papifera62, B. nigra63, and B. utilis36,58. It appears that B. utilis, during the growing season from May to October maintains high leaf conductance. These results suggest that B. utilis trees tend to have higher transpiration rates in response to increased solar radiation and evaporative demand during the pre-monsoon season, while transpiration is relatively lower during the monsoon season. The highest gw was seen during and immediately after the monsoon season. This occurrence may be attributed to the presence of abundant moisture in the soil due to the occurrence of bright and sunny days after rainfall. A reduction in gw during dry months, coincided with the period when the Ψ of trees reached its lowest point64. A considerable variation across the species was also proposed in terms of the extent of decrease in gw in response to unfavourable environmental circumstances37.

Phenological phases in plants are influenced by environmental cues, including temperature and day length, which can be altered by climate change. The life cycle of most deciduous plants consists of distinct vegetative and reproductive phases65. The seasonality of Himalayan trees, including B. utilis phenology, is primarily influenced by the length and severity of seasonal drought66. It is worth noting that even trees of the same species may encounter varying levels of drought-induced stress67. In this study, the leafing and flowering of B. utilis occurred between early May and July, which aligns with previously reported timings46,68. A substantial amount of snow, slow melting, and a colder winter appeared to be positively correlated with B. utilis growth during the following growing season65. The onset of leaf fall in B. utilis coincided with the lowering of autumnal temperatures. A longer wet period resulted in an extended growth phase, which is advantageous for extending the life of the leaves, using perennial deciduous plants.

Phenological events, such as bud burst, flowering, leaf initiation, seed fall, and leaf fall, are strongly influenced by temperature and precipitation patterns and are sensitive to changes in environmental circumstances. Temperature plays a significant role in triggering phenological events. Warmer temperatures can accelerate the onset of bud bursting and flowering, while cooler temperatures can delay these events. Precipitation, particularly rainfall, also affects phenology by providing necessary moisture for growth and development. However, it’s important to note that the relationship between temperature, precipitation, and phenological events can vary depending on the species of tree, its geographical location, and local environmental conditions. Tree Ψ has a direct relation with the temperature and precipitation and it affects the species reproductive and vegetative phases of a species. Understanding the relationship between phenology and Ψ is essential for assessing the species’ resilience and vulnerability to changing environmental conditions, such as drought or altered precipitation patterns. The twig ΨPD of B. utilis trees was monitored throughout the phenological phases and it consistently maintained a value higher than − 0.77 MPa. During the process of leaf development, the ΨPD of the twig exhibited an initial high value. Subsequently, as the leaves reached maturity, there was a steady decrease in ΨPD of twigs until the month of June. However, in July, there was an observed rise in ΨPD. This observed pattern indicates that the tree exhibits adequate water availability during the early phases of leaf formation, but encounters escalating water stress as the leaves progress in their development. During the process of blooming, the ΨPD of the twig exhibited a value of − 0.72 MPa at the onset of flowering, which then increased progressively to − 0.17 MPa after the flowering phase this indicates water availability does not impose substantial constraints on reproductive activities. The correlation between phenological phases and ΨPD of twig in B. utilis underscores the tree’s capacity to regulate its Ψ in response to the requirements of various developmental stages. Ensuring sufficient Ψ levels throughout vital phenological stages is essential for achieving effective reproduction and leaf withering.

It is apparent from the study that the water potential of the birch tree does not reach the lethal levels to curtail phenological and physiological activities. The species’ ability to maintain high-pressure potential under varying soil moisture conditions is evident by its ability to adjust osmotically, which assists in the absorption of water particularly during the growing season, and makes maximum use of the period during which it has leaves as evident from its higher leaf conductance. The phenological pattern indicates that the tree exhibits adequate water availability during the early phases of leaf formation, but encounters escalating water stress as the leaves progress in their development. The study emphasizes the birch tree’s adaptive mechanisms to sustain adequate water availability during critical growth phases, while also highlighting the ongoing challenges posed by advancing leaf development. Some of our findings are difficult to explain and might need more observation. Furthermore, an extended period of research on water relations and many other ecological parameters is required in the treeline areas to understand the impacts of climate change and simultaneously facilitate actions related to the conservation and management of this Critically Endangered species.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Sharma, R. & Uniyal, S. K. Vegetation patterns of treeline ecotone in the Pangi Valley, Western Himalaya. Proceedings of 1st Himalayan Researchers Consortium. 31–39 (2019).

Holtmeier, F. K. Mountain Timberline: Ecology, patchiness and dynamics (Advances in Global Change Research) Vol. 36 (Springer, 2009).

Cairns, D. M. & Moen, J. Herbivory influences treeline. J. Ecol. 92(6), 1019–1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2004.00945.x (2004).

Zobel, D. B. & Singh, S. P. Himalayan forests and ecological generalizations. Bioscience 47, 735–756 (1997).

Maletha, A., Maikhuri, R. K. & Bargali, S. S. Criteria and indicator for assessing threat on Himalayan birch (B. utilis) at timberline ecotone of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve: A world heritage site, Western Himalaya, India. Environ. Sustain. Indic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2020.100086 (2020).

Wani, Z. A. & Pant, S. Betula utilis D. Don: An ecologically and economically important timberline species of Himalayan Region in Jeopardy. Bot. Rev. 87, 377 (2021).

Mohapatra, J. et al. Modelling Betula utilis distribution in response to climate-warming scenarios in Hindu-Kush Himalaya using random forest. Biodivers. Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01731-w (2019).

Bobrowski, M., Gerlitz, L. & Schickhoff, U. Modelling the potential distribution of Betula utilis in the Himalaya. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 11, 69–83 (2017).

Singh, N., Tewari, A., Shah, S. & Mittal, A. Catkin maturation timing and seed germination in Betula utilis (D. Don) in the western Himalayan treeline area of Uttarakhand. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 11(2), 145–151 (2020).

Singh, N., Tewari, A., Shah, S. & Mittal, A. Treeline species: Regeneration status and seedling dynamics in Western Himalayan Region. Environ. Ecol. 38(3B), 725–732 (2020).

Shaw, K. et al. The Red List of Betulacea', BGCI Descanso House 199 Kew Road, Richmond Survey, TW9 3BW United Kingdom, 68 (2014).

Pant, S. & Pant, V. S. Status and conservation management strategies for threatened plants of Jammu and Kashmir. J. Phytol. 3(7), 50–56 (2011).

Kotru, R. et al. Transforming Mountain forestry in the Hindu Kush Himalayas: Toward a third-generation forest management paradigm. ICIMOD Working Paper 2015/9. Kathmandu: ICIMOD (2015).

Bargali, K. & Tewari, A. Growth and water relation parameters in drought-stressed Coriaria nepalensis seedlings. J. Arid Environ. 58(4), 505–512 (2004).

Arndt, S. K., Clifford, S. C., Wanek, W., Jones, H. G. & Popp, M. Physiological and morphological adaptations of the fruit tree Ziziphus rotundifolia in response to progressive drought stress. Tree Physiol. 21(11), 705–715 (2001).

Kozlowski, T. T., Kramer, P. J. & Pallardy, S. G. The physiological ecology of woody plants (Academic Press, 1991).

Singh, N., Tewari, A., Shah, S. & Mittal, A. Tree regeneration pattern and size class distribution in anthropogenically disturbed sub-alpine treeline areas of Indian Western Himalaya. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 8(8), 537–546 (2019).

Fort, C., Muller, F., Label, P., Granier, A. & Dreyer, E. Stomatal conductance, growth and root signaling in Betula pendula seedlings subjected to partial soil drying. Tree Physiol. 18, 769–776 (1998).

Poudyal, K. Plant water relations, phenology and drought adaptations strategy of Himalayan oaks; Quercus lanata in Phulchowki Hill, Nepal. Sci. Secur. J. Biotechnol. 2, 99–110 (2013).

Osonubi, O. & Davies, W. J. Solute accumulation in leaves and roots of woody plants subjected to water stress. Oecologia 32, 323–332 (1978).

Ranney, T. G., Bir, R. E. & Skroch, W. A. Comparative drought resistance among six species of birch (Betula): Influence of mild water stress on water relations and leaf gas exchange. Tree Physiol. 8, 351–360 (1991).

Peters, R. L. et al. Contrasting stomatal sensitivity to temperature and soil drought in mature alpine conifers. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 1674–1689 (2019).

Negi, V. S., Pathak, R., Rawal, R. S., Bhatt, I. D. & Sharma, S. Long-term ecological monitoring on forest ecosystems in Indian Himalayan Region: Criteria and indicator approach. Ecol. Indic. 102, 374–381 (2019).

Maletha, A., Maikhuri, R. K. & Bargali, S. S. Population structure and regeneration pattern of Himalayan birch (Betula utilis D. Don) in the timberline zone of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, Western Himalaya, India. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 7(3), 248–257 (2023).

Kanka, R., Kollar, J. & Barancok, P. Monitoring of climatic change impacts on alpine vegetation in the Tatry MTS—first approach. Ekologia (Bratislava). 24, 411–418 (2005).

Chawla, A. et al. Long-term ecological and biodiversity monitoring in the Western Himalaya using satellite remote sensing. Curr. Sci. 102, 1143–1156 (2012).

Sharma, C. M., Baduni, N. P., Gairola, S., Ghildiyal, S. K. & Suyal, S. Tree diversity and carbon stocks of some major forest types of Garhwal Himalaya, India. For. Ecol. Manag. 260, 2170–2179 (2010).

Gairola, S., Sharma, C. M., Suyal, S. & Ghildiyal, S. K. Composition and diversity of five major forest types in moist temperate climate of the western Himalayas. For. Stud. China 13, 139–153 (2011).

Kala, C. P. Local preferences of ethnobotanical species in the Indian Himalaya: Implications for environmental conservation. Curr. Sci. 93, 1828–1834 (2007).

Phondani, P. C., Maikhuri, R. K., Rawat, L. S., Farooquee, N. A. & Kala, C. P. Ethnobotanical uses of plants among the Bhotiya tribal communities of Niti valley in Central Himalaya, India. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 8, 233–244 (2010).

Gairola, S., Sharma, C. M., Suyal, S. & Ghildiyal, S. K. Species composition and diversity in mid-altitudinal moist temperate forests of the western Himalaya. J. For. Sci. 27, 1–15 (2011).

Sharma, C. M., Ghildiyal, S. K., Gairola, S. & Suyal, S. Vegetation structure, composition and diversity in relation to the soil characteristics of temperate mixed broad-leaved forest along an altitudinal gradient in Garhwal Himalaya. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2, 39–45 (2009).

Sharma, C. M., Baduni, N. P., Gairola, S., Ghildiyal, S. K. & Suyal, S. The effect of slope aspects on forest compositions, community structures and soil properties in natural temperate forests in Garhwal Himalaya. J. For. Res. 21, 331–337 (2010).

Gairola, S., Sharma, C. M., Ghildiyal, S. K. & Suyal, S. Chemical properties of soils in relation to forest composition in moist temperate valley slopes of Garhwal Himalaya, India. Environmentalist 32, 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-012-9420-7 (2012).

Rawat, D. S., Tiwari, P., Das, S. K. & Tiwari, J. K. Tree species composition and diversity in montane forests of Garhwal Himalaya in relation to environmental and soil properties. J. Mt. Sci. 17(12), 3097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-019-5761-8 (2020).

Tewari, A., Shah, S., Singh, N. & Mittal, A. Treeline species in Western Himalaya are not water stressed: A comparison with low elevation species. Trop. Ecol. 59(2), 313–325 (2018).

Singh, N., Tewari, A., Shah, S. & Mittal, A. Seasonal water relations and stress tolerance of quercus semecarpifolia (Smith) in treeline areas of Western Himalaya, India. Vegetos https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-023-00665-7 (2023).

Singh, N., Tewari, A., Shah, S. & Mittal, A. Water relations and phenological events of two treeline Rhododendron species in Indian western Himalaya. Sylwan 163(10), 64–76 (2019).

Jackson, M. L. Soil chemical analysis (Prentice Hall, 1958).

Zobel, D. B., Garkoti, S. C., Singh, S. P., Tewari, A. & Negi, C. M. S. Patterns of water potential amongst forest types of the central Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 80, 774–779 (2001).

Ritchie, G. A. & Hinckley, T. M. The pressure chamber as an instrument for ecological research. In Advances in ecological research (ed. Macfadyen, A.) 165–254 (Academic Press, 1975).

Pallardy, S. D., Pereira, J. S. & Parker, W. C. Measuring the state of water in tree systems’. In Techniques and approaches in forest tree ecophysiology (eds Lassoie, J. & Hinckley, T. M.) 27–76 (CRC Press, 1991).

Garkoti, S. C., Zobel, D. B. & Singh, S. P. Variation in drought response of sal (Shorea robusta) seedlings. Tree Physiol. 23, 1021–1030 (2003).

Singh, N., Ram, J., Tewari, A. & Yadav, R. P. Phenological events along the elevation gradient and effect of climate change of Rhododendron arboreum Sm. Kumaun Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 108(1), 106–110 (2015).

Singh, N. & Mittal, A. Response of phenological events of Aesculus indica Colebr. to climate change along an altitudinal gradient in Kumaun Himalaya. Int. J. Environ. 8(1), 1–16 (2019).

Singh, P. & Negi, G. C. S. Treeline species phenology: Shoot growth, leaf characteristics and nutrient dynamics. Trop. Ecol. 59(2), 297–311 (2018).

Moza, M. K. & Bhatnagar, A. K. Phenology and climate change. Curr. Sci. 9, 243–244 (2005).

Singh, S. P. Research on Indian Himalayan treeline ecotone: An overview. Trop. Ecol. 59(2), 163–176 (2018).

Czajka, B., Łajczak, A., Kaczka, R. J. & Nicia, P. Timberline in the Carpathians: An overview. Geogr. Pol. 88(2), 7–34 (2015).

Malik, R. A. & Sukumar, R. Response of radial growth in Abies pindrow (Royle ex D.Don) Royle to Climate at treeline ecotone in the northwestern Himalaya. In Ecology of himalayan treeline ecotone (eds Singh, S. P. et al.) 483–505 (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4476-5_20.

Müller, M., Schwab, N., Schickhoff, U., Böhner, J. & Scholten, T. Soil temperature and soil moisture patterns in a Himalayan alpine treeline ecotone. Arctic Antarct. Alp. Res. 48, 501–521 (2016).

Schickhoff, U. et al. Do Himalayan treelines respond to recent climate change? An evaluation of sensitivity indicators. Earth Syst. Dyn. 6, 245–265 (2015).

Sigdel, S. R. et al. Moisture-mediated responsiveness of treeline shifts to global warming in the Himalayas. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 5549–5559 (2018).

Lyu, L. et al. Drought limitation on tree growth at the northern hemisphere’s highest tree line. Dendrochronologia 53, 40–47 (2019).

Schwab, N. et al. Ecological relationships at a near-natural treeline, Rolwaling valley, Nepal Himalaya: Implications for the sensitivity to climate change. Erdkunde 74, 15–44 (2020).

Korner, C. Treelines will be understood, once the difference between a tree and a shrub is’. Ambio (Festschrift T. Callaghan) 41, 197 (2012).

Mayr, S. Limits in water relations’. In Trees at their upper limit Vol. 10 (eds Wieser, G. & Tausz, M.) 145–162 (Springer, 2007).

Singh, S. P. et al. Indian Himalayan timberline ecotone in response to climate change—initial findings. Curr. Sci. 120(5), 859–871 (2021).

Rieger, M. Offsetting effects of reduced hydraulic conductivity and osmotic adjustment following drought. Tree Physiol. 15, 379–385 (1995).

Ritchie, G. A. & Shula, R. G. Seasonal changes of tissue water relations in shoots and root systems of Douglas-fir seedlings. For. Sci. 30, 538–548 (1984).

Abrams, M. D. Adaptations and responses to drought in Quercus species of North America. Tree Physiol. 7, 227–238 (1990).

Daley, M. J. & Phillips, N. G. Interspecific variation in nighttime transpiration and stomatal conductance in a mixed New England deciduous forest. Tree Physiol. 26(4), 411–419 (2006).

Barnard, D. M. & Bauerle, W. L. The implications of minimum stomatal conductance on modeling water flux in forest canopies. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 118, 1322–1333 (2013).

Poudyal, K., Jha, P. K., Zobel, D. B. & Thapa, C. B. Patterns of leaf conductance and water potential of five Himalayan tree species. Tree Physiol. 24, 689–699 (2004).

Rai, I. D., Adhikari, B. S., Rawat, G. S. & Bargali, K. Community structure along timberline ecotone in relation to micro-topography and disturbances in western Himalaya. Not. Sci. Biol. 4(2), 41–52 (2012).

Mooney, H. A., Medina, E. & Bullock, S. H. Neotropical deciduous forests (Academic Press, 1995).

Singh, K. P. & Kushwaha, C. P. Emerging paradigms of tree phenology in dry tropics. Curr. Sci. 89, 964–975 (2005).

Bisht, V. K., Nautiyal, B. P., Kuniyal, C. P., Prasad, P. & Sundriyal, R. C. Litter production, decomposition, and nutrient release in subalpine forest communities of the northwest Himalaya. J. Ecosyst. 2014, 294867. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/294867 (2014).

Joshi, R., Sambhav, K. & Singh, S. P. Near surface temperature lapse rate for treeline environment in western Himalaya and possible impacts on ecotone vegetation. Trop. Ecol. 59(2), 197–209 (2018).

Funding

This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2024R339) at King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Data collection, Data analysis, Writing an original draft, Editing and Finalized, N.S.; Conceptualization, Methodology, Data collection, Visualization, Supervision, Review and Finalized, A.T. and V.J.; Conceptualization, Methodology and Data collection, S.S.; Conceptualization, Methodology and Data collection, A.M., S.M. and A.A.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, N., Mittal, A., Tewari, A. et al. Exploring water relations and phenological traits of Betula utilis (D. Don) in western Himalayan treeline ecotone. Sci Rep 14, 20853 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66682-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66682-x

This article is cited by

-

Carbon capture potential of high-altitude treeline forming forests in Western Himalaya, India

Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy (2025)

-

SSR marker-based characterization of the timberline Himalayan Birch (Betula utilis D. Don) for genetic diversity and population structure

The Nucleus (2025)