Abstract

The recent pandemic caused by COVID-19 is considered an unparalleled disaster in history. Developing a vaccine distribution network can provide valuable support to supply chain managers. Prioritizing the assigned available vaccines is crucial due to the limited supply at the final stage of the vaccine supply chain. In addition, parameter uncertainty is a common occurrence in a real supply chain, and it is essential to address this uncertainty in planning models. On the other hand, blockchain technology, being at the forefront of technological advancements, has the potential to enhance transparency within supply chains. Hence, in this study, we develop a new mathematical model for designing a COVID-19 vaccine supply chain network. In this regard, a multi-channel network model is designed to minimize total cost and maximize transparency with blockchain technology consideration. This addresses the uncertainty in supply, and a scenario-based multi-stage stochastic programming method is presented to handle the inherent uncertainty in multi-period planning horizons. In addition, fuzzy programming is used to face the uncertain price and quality of vaccines. Vaccine assignment is based on two main policies including age and population-based priority. The proposed model and method are validated and tested using a real-world case study of Iran. The optimum design of the COVID-19 vaccine supply chain is determined, and some comprehensive sensitivity analyses are conducted on the proposed model. Generally, results demonstrate that the multi-stage stochastic programming model meaningfully reduces the objective function value compared to the competitor model. Also, the results show that one of the efficient factors in increasing satisfied demand and decreasing shortage is the price of each type of vaccine and its agreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent epidemic caused by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is considered one of the historically unprecedented disasters. The first patients were observed in Wuhan, China, and after a few months, it spread over the world. Governments tried to control the epidemic through different ways such as necessities supply, quarantining, and culture building, but based on the World Health Organization (WHO) report, most countries were unsuccessful in epidemic control. As of November 21, 2023, there have been more than 6.94 million deaths have been reported to WHO, showing the countries’ inability to control the epidemic. Vaccination seems to be the only way to control the disease. Specialists and pharmacists began trying vaccine production as soon as the epidemic outbreak, and some of them have succeeded recently. However, one of the key problems for governments is identifying high-quality and low-risk suppliers. Overseas suppliers prefer to supply their country’s requirements first, and then other countries. Limited vaccine production is not enough for the more than 7.8 billion world population, therefore the effective supply, distribution, and delivery of the COVID-19 vaccine to the populace are as necessary as its development and mass production 1.

The severe pandemic caused by COVID-19 has created an urgent need to improve and strengthen the coordination of Vaccine Supply Chains (VSCs). Designing a practical and effective vaccine distribution network can be a valuable help to managers of such supply chains 2. On the other hand, the global economy has been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to substantial disturbances in supply chains and logistics processes. The modern emergency logistics system has faced significant challenges in maintaining circulation and managing supply chain interruptions, with outdated infrastructure and equipment further exacerbating the issue. A multi-channel network model is designed to optimize different factors according to their importance. The network total cost and the price of vaccines are the main factors in the vaccine distribution network design 3.

Demand points may have different urgency degrees in VSC network design. Hence, it is important to prioritize available vaccines given the limited supply in each period in the last echelon of the supply chain 4. Some of the studies have proposed models to optimize distribution network design considering priority. Researchers have shown that choosing the appropriate prioritization policy can prevent infection transmission and mortality 5. The aim is to define the optimal distribution schedule to the populace. Distribution networks based on social equity designed for the COVID-19 vaccine are also being investigated. The VSC models can consider demand priorities which may be a function of pandemic characteristics or the demand source itself.

The modern emergency logistics system involves strengthening cooperation and coordination between the government and the public, establishing specialized emergency agencies for unified command, and utilizing digital technologies to enhance process visibility and automation for quicker response and increased resilience. Vaccination is the most effective strategy to face COVID-19, but transportation, warehousing, lead time, and distributing vaccines in modern emergency logistics is a major challenge. Ensuring that vaccines are available to recipients adds to this challenge 6. Uncertainty in supply is a common occurrence in a real supply chain, and it is essential to address this uncertainty in planning models. Uncertainty is inherent in all predictions, and the extent of uncertainty is directly related to the timeframe of the prediction. To minimize the effect of uncertainty on supply chain performance, more comprehensive models can be used. These models can consider extreme uncertainties that may lead to serious disruptions in the supply chain 7. The goal is to demonstrate how modeling can address uncertainties in the number of vaccines supplied by each supplier. In addition to supply, sometimes because of insufficient information on some parameters like the price and quality of vaccines, we can use the opinion of an expert (experts) to predict them based on the situation.

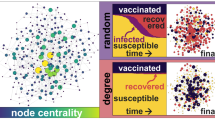

In addition, blockchain technology can improve information availability and transparency in VSC networks. This technology can enhance transparency by providing real-time visibility into the supply chain processes. This can be achieved by IoT tools in centers and vehicles, which convert the physical flow into a digital flow, generating blocks that can be linked to create a chain of blocks. Also, blockchain technology ensures the security of the supply chain by providing an immutable and tamper-proof ledger. This ensures that all transactions and data are secure and trustworthy, reducing the risk of errors, fraud, and counterfeiting. To facilitate integration, centers and vehicles are equipped with IoT tools that enable the conversion of the physical flow into a digital flow, generating blocks. This ensures that at least one member from the preceding level and one member from the next level are linked to the equipped member, creating a chain of blocks. Transparency serves as the key objective function in the mathematical modeling of the supply chain. Blockchain technology can be used to optimize the supply chain processes by ensuring that all data is accurate, up-to-date, and accessible to all stakeholders. On top of that, smart contracts can be used to automate routine tasks and ensure compliance throughout the supply chain processes. These contracts can be programmed to trigger specific actions based on predefined conditions, such as delivery confirmation or quality inspection. Finally, by implementing blockchain technology in the VSC network, it is possible to significantly improve transparency, security, and efficiency across the vaccine supply and distribution network 8.

The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the urgent need for a more efficient emergency logistics system while accelerating the adoption of digital technologies like blockchain in the logistics sector, and strengthening relationships with upstream suppliers. To address the mentioned issues, this work develops a novel mathematical model for designing a network of COVID-19 vaccine supply chains. On this subject, a multi-channel network model is created to optimize total cost. Furthermore, we integrated blockchain technology into the VSC to create a blockchain-enabled multi-tier VSC network, with the aim of enhancing transparency as our secondary objective. In addition, this paper aims to address the uncertainty in the number of vaccines supplied by each supplier to enable network decisions in the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A scenario-based Multi-Stage Stochastic Programming (MSSP) approach is presented to handle the inherent uncertainty in multi-period planning horizons. The approach specifies locations of Cross-Dock Centers (CDCs) at the beginning of the planning horizon, and other decision variables are made based on the realization of uncertainty after each period. This approach is used to model the dynamic uncertainty in VSC network design. Vaccine assignment is based on two main policies including age and population-based prioritization. Moreover, the model is validated and tested using a real-world case study. However, the study is not limited to this instance, and the proposed approaches and key findings can be generalized to use many other real-life cases.

The goal of this research is to answer the following questions:

-

How to model a multi-channel COVID-19 VSC network to minimize total cost?

-

Which candidate locations of CDCs should be activated to maximize the efficiency of the proposed network?

-

What are the impacts of priority for vaccine assignment on the proposed model?

-

How to cope with the stochastic vaccine supply of suppliers to solve the proposed mathematical model?

-

How to deal with the fuzzy price and quality of vaccines in the VCS network design?

-

How to increase the transparency, security, and efficiency in the proposed VSC network?

Therefore, this study proposes a blockchain-based multi-channel VSC network to address COVID-19 under hybrid uncertainties. The research introduces a novel scenario generation method and the MSSP approach to manage uncertain supply, fuzzy programming for fuzzy price and quality of vaccines, and age and population-based prioritization in the VSC network design. Unlike the existing research, which has primarily focused on blockchain adoption in networks and supply chains, this study is grounded in optimization models formulated using operations research methodologies. This distinctive approach sets it apart from the existing body of literature on the subject. The paper's significance lies in its practical application of these methodologies in a real case based on Iran data, providing valuable insights into the VSC management during the COVID-19 epidemic. Therefore, the major contributions of this paper are presented as follows:

-

A multi-channel multi-period VSC network design is proposed to minimize the total cost of the network as well as maximize transparency based on the blockchain technology.

-

A novel method of scenario generation and creating an efficient scenario tree is used.

-

The MSSP approach is provided to deal with the uncertain supply.

-

Fuzzy programming is applied to face the fuzzy price and quality of vaccines.

-

Vaccine assignment is considered based on age and population-based prioritization in the VSC network design.

-

A real case study is applied using Iran data to test the developed methodologies’ efficacy and validity in real life.

The study will proceed as outlined below: In Section "Literature review", the literature of the related field is extensively reviewed. Section "Problem description and mathematical modeling" gives the problem description and model formulation. Section "Solution methodology" is assigned to the MSSP formulation for dealing with the uncertain supply, the fuzzy method for facing uncertain prices and quality of vaccines, and a blockchain platform for the COVID-19 VSC network is suggested. In Section "Implementation and Results", the real case study is defined extensively. The next section reports the results and sensitive analysis of the generated instances and the case study. After that, Section "Conclusion and future research" highlights the management implications of the problem. Ultimately, the conclusion and future studies are dedicated in Sect. 8.

Literature review

In this section, the most related studies in the field of COVID-19 VSC network design are reviewed. The following review papers examine the main topics covered in this paper from different perspectives. In the scope of VSC, Duijzer et al. 9 provided a classification for the supply chain literature, including production, product, distribution, and allocation, to structure it and recognize future research avenues. In another study, Chowdhury et al. 10 reviewed papers on the COVID-19 epidemics in supply chain disciplines up to October 2020. In the following, we review previous studies in several main categories, the multi-channel supply chain network, the COVID-19 VSC design, these networks design under uncertainty, and the role of blockchain technology in supply chain network design. Moreover, a summary of different existing VSC network designs in COVID-19 literature is provided in Table 1.

Multi-channel supply chain network

Nowadays, the utilization of a multi-channel distribution system is on the rise, and choosing the right distribution channel according to the product type and the necessary number of transportation vehicles is a critical consideration. In the first research in this field, Chopra 11 presented a structure for distribution network design in a supply chain by introducing several distribution channels. Then, to identify the best option among the introduced channels, he proposed several cost and service criteria and examined the strengths and weaknesses of the introduced channels. In another paper, Cintron et al. 12 extended a multi-criteria Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model to create the supply chain distribution network for a consumer goods corporation. In their work, they optimized the best possible network configuration for each member of the supply chain. In their developed model, they proposed four channels for the flow of products from the factories to the customers and optimized the problem according to several different criteria. Liu et al. 13 suggested a location model for a multi-channel supply chain network that allocates online orders to the regional capacities. Additionally, Zhang et al. 14 presented a new multi-channel model for distribution network design. Their proposed model has many advantages for customers by providing services directly from the distribution network centers. To solve the developed optimization model, they used a modified artificial bee colony method and used numerical experiments to evaluate its efficiency. Also, Vafaei et al. 15 proposed a multi-channel multi-product supply chain distribution network model for sustainable distribution network design, considering multi-transportation modes. They used Digikala company to assess the practicality of the proposed optimization model. Khorshidvand et al. 16 designed a multi-level multi-channel supply chain to maximize the total profit considering the profitability of entities. Moreover, a novel model for a multi-channel closed-loop supply chain network was provided by Niranjan et al. 17. The aim of the authors was to minimize the total cost of pollution emissions from all transportation. Recently, Niranjan et al. 18 extended the mathematical model for the sustainable multi-channel closed-loop supply chain and solved the model by a modified particle swarm optimization algorithm. While there is a gap in research on multi-channel VSCs in general, the specific supply chain for the COVID-19 vaccine, which is the focus of this paper, has not yet been designed.

COVID-19 vaccine supply chain design

The COVID-19 epidemic has created a critical challenge to designing effective VSC networks. To address this issue, Abbasi et al. 19 proposed a Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP) problem to provide a green VSC network to show trade-offs between green supply chain aspects. Alizadeh et al. 20 suggested a new COVID-19 VSC with three main goals including cost minimization, maximizing prioritization, and minimizing maximum lost customer demand. The other objective leads to creating justice considering minimizing the maximum lost demand. Habibi et al. 21 developed a COVID-19 VSC network using a two-phase optimization approach. At first, the population was divided into groups based on priority for vaccination. Then, the Distribution Centers (DCs) were located, inventory policies were established, and routing decision variables were made to minimize the total cost. From another viewpoint, Rahman et al. 22 investigated a COVID-19 vaccine distribution problem and proposed a bi-objective mathematical model that considers both long-term and short-term decisions. Recently, Valizadeh et al. 23 extended an optimization model for the COVID-19 VSC in which mortality risk was considered. The authors utilized a robust model to cope with demand uncertainty, and several meta-heuristic algorithms were proposed to solve their model. More recently, Kamran et al. 24 designed a VSC network under COVID-19 conditions using system dynamics and solved it with artificial intelligence algorithms. Furthermore, a responsive-green-cold VSC network using Internet-of-Things (IoT) was developed by Goodarzian et al. 25 to improve the accuracy and justice of vaccine injection with existing priorities. In another study, Goentzel et al. 26 extended an MIP mathematical model to maximize the coverage of immunization within limited budgets and allocate resources based on real-world data and internal demand. However, this study is unique as it focuses on designing a multi-channel VSC for the COVID-19 vaccine, incorporating blockchain technology. It goes beyond previous works that focused on cost minimization and prioritization by considering age and population-based vaccine assignment.

COVID-19 vaccine supply chain under uncertainty

During the recent COVID-19 outbreak, Sazvar et al. 27 suggested a mixed resilient-sustainable model to design a VSC network to make decisions. To address the inherent uncertainty of parameters, the researchers tailored a novel robust fuzzy optimization technique and applied multi-choice goal programming to manage the multiple objectives. One notable study by Mohammadi et al. 28 proposed a multi-objective optimization model for COVID-19 vaccine distribution under uncertainty. The authors applied a scenario-based approach to account for the variability in demand and supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic. Besides, Bani et al. 29 designed a multi-objective model for the COVID-19 vaccine waste network under uncertainty considering economic and environmental objectives. They applied a robust optimization method to cope with uncertainty vaccination tendency rate and used a Lagrangian relaxation approach for large-size problems. Shiri and Ahmadizar 30 designed a VSC network to achieve an equitable system in the COVID-19 era, and they applied scenario-based uncertain data for demand parameters. Recently, Moadab et al. 31 suggested a model to optimize the COVID-19 pandemic supply chain for polymerase chain reaction diagnostic tests using stochastic programming. Under supply uncertainty, Wang et al. 32 extended a two-stage robust model to optimize vaccination facility location and scheduling. On this subject, Kochakkashani et al. 33 supported Decision-Makers (DMs) during epidemics by proposing a new mathematical model using various pharmaceuticals and their features using K-means clustering. They applied unsupervised learning for a multi-commodity supply chain. Gilani et al. 34 extended a COVID-19 VSC using domestic/foreign supply networks and addressed robust models’ high conservatism using a data-driven model. Recently, Tirkolaee et al. 35 proposed a new two-stage decision support structure for configuring multi-echelon supply chain networks under an uncertain environment. Moreover, Lotfi et al. 36 suggested a new model using a robust stochastic programming method and considered limiting CO2 emissions, considering flexible capacity and reliability of facilities. More recently, Taghipour et al. 37 provided a multi-objective optimization model for the robust VSC network to minimize cost and maximize reliability. The proposed study goes beyond previous research by incorporating blockchain technology, considering real-world data, and employing an MSSP approach to handle supply uncertainties.

Application of blockchain for supply chain network

The integration of blockchain technology and SCM has been explored in several studies. Here are some key findings and insights from these studies:

Blockchain and supply chain management integration

Queiroz et al. 38 presented a blockchain technology that has the potential to disrupt traditional SCM models by providing transparency, security, and efficiency. The electric power industry showed a relatively mature understanding of blockchain-SCM integration, particularly through the use of smart contracts.

Case study: sustainable fishing

Haughton et al. 39 used a hybrid blockchain to track the seafood lifecycle from "bait to plate" in a case study of sustainable fishing. The system included transaction entry, block validation, and data immutability to ensure transparency and security throughout the supply chain.

Enablers of blockchain adoption

Agi and Jha 40 proposed a comprehensive framework for blockchain adoption in SCM that identified several enablers, including management commitment, cooperation between supply chain partners, and regulatory support. Also, Majdalawieh et al. 41 constructed a system using blockchain and IoT to supervise the operations of the processed poultry food supply chain network. The authors recommended the implementation of Ethereum smart contracts to broaden a transparent structure.

Real-world applications

Maersk used an IBM blockchain solution to track containers globally, while Catina Volpone Vineyard and Ernst and Young's EZ Lab developed a blockchain-based solution for wine supply chain transparency 40. In addition, blockchain technology can improve supply chain coordination, process efficiency, and sustainability by providing traceability and making product information digitally available 40.

Optimization models

Waller et al. 42 proposed fuzzy optimization models for supply chain network design, considering open innovation and blockchain technology as a safe platform for collecting and approving ideas. They integrated bi-objective optimization models with blockchain technology to optimize supply chain design and achieve efficient solutions. Also, Rahmanzadeh et al. 43 extended a fuzzy optimization model considering open innovation for supply chain network design. In addition, they proposed blockchain technology as a safe platform for collecting, refining, and approving ideas. They used a real case to test the practicality of the proposed mathematical model. Integration and transparency play an important role in the VSC during an epidemic situation. More recently, Babaei et al. 8 proposed a bi-objective optimization model and integrated the three-level supply chain design based on blockchain technology. They utilized the B&E algorithm and fuzzy goal programming to solve their mathematical model, resulting in both optimal and efficient solutions. Antal et al. 44 suggested a blockchain platform for the VSC to ensure efficient vaccination during the COVID-19 outbreak. In a similar effort, Rani et al. 45 designed a supply chain network guaranteed with blockchain to achieve the optimum route of a product. A genetic algorithm-based method was applied to solve the model.

These studies highlight the potential of blockchain technology to transform SCM by enhancing transparency, security, and efficiency. They also emphasize the importance of management commitment, cooperation, and regulatory support for successful blockchain adoption in SCM.

Table 1 shows that special regard has been paid to the design of the COVID-19 VSC network so far, confirming the need for additional research in this area. To address the literature gaps, this study creates a conceptual framework of a multi-channel COVID-19 VSC network based on multi-period modeling, which is then applied to a real-life situation. Uncertainty in data is a common occurrence in a real supply chain, and it is essential to address this uncertainty in modeling. This paper, for the first time, addresses a mixed approach to dealing with the uncertain environment for a COVID-19 VSC network. A scenario-based MSSP approach is presented for supply. In addition, fuzzy programming is applied to address the fuzzy price and quality of vaccines. Prioritizing the available vaccines is crucial due to the limited supply, which has been less considered. Also, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study has so far proposed a blockchain-enabled VSC network for managing COVID-19. Hence, an effective design for the COVID-19 VSC network is crucial to maximize transparency. Therefore, this study presented a mathematical model for an integrated blockchain-enabled multi-channel VSC network for the COVID-19 pandemic, in which data uncertainty is addressed with a scenario-based MSSP approach.

Problem description and mathematical modeling

In this section, a multi-echelon multi-channel VSC management system is investigated. In this respect, we describe the problem and mathematical formulation in Subsections "Problem description" and "Mathematical model", respectively, as follows:

Problem description

We proposed a new mathematical model of how to supply and allocate limited COVID-19 vaccines over demand points. A planning horizon divided into multiple periods is investigated. In this network, suppliers are classified into two main categories in terms of delivery time; Some suppliers can only supply for the next period (Agreement A); Other suppliers, moreover to having the first group option, can provide for the current period but at a higher price (Agreement B). On the other side, according to WHO rules, the development of a new vaccine is done in several phases to have the best possible performance. Besides, vaccine manufacturers have to carefully control the quality of vaccines produced. However, once vaccines start being administered, monitoring is necessary to ensure the quality of vaccines. Due to the high importance of vaccine delivery time to the Health Centers (HCs), we have developed the proposed network as a multi-channel where the vaccines can be sent from the Ministry of Health (MoH) to the HC directly, the DCs, or the CDCs. As can be seen in Fig. 1, all of the channel’s vaccine flow starts from the MoH and finishes at HCs. Vaccine assessment is based on two main policies:

-

i.

Prioritizing high-risk individuals over low-risk groups based on their age.

-

ii.

Population-based prioritization gives more priority to areas with higher populations.

According to the mentioned descriptions, the proposed VSC network consists of five main parts including several vaccine suppliers, MoH, CDCs, DCs, and HCs based on Fig. 1. We have considered the problem under the following assumptions:

-

A multi-period multi-channel COVID-19 VSC network is proposed;

-

Five echelons form the VSC network: Suppliers, MoH, CDCs, DCs, and HCs;

-

The number of supplied vaccines by each supplier is considered uncertain information;

-

The candidate locations are assumed for establishing CDCs;

-

The vaccine productions are limited by suppliers;

-

Two types of agreement are considered for supplying vaccines from suppliers, Agreements A and B;

-

Some suppliers can supply vaccines for the current period by Agreement B;

-

Each supplier offers a price for the vaccine unit, while the price of each vaccine unit for immediate supply is more expensive;

-

Vaccine assignment is based on two main policies, age and population-based prioritization.

We develop an MSSP model supposing an uncertain and multi-period decision-making environment (Section "Solution methodology"), to optimize the tactical and strategic decisions of the network. In the developed MSSP, decisions on supplier selection, the location of CDCs, the allocation and flow between different facilities, the optimum channel, and transportation decisions must be made. The strategic decision in the introduced network is related to the location and construction of CDCs, which must be realized in the first stage and before the realization of stochastic parameters. This means that these decisions are made at the outset and will not change in the future. The following subsection presents a developed mathematical model for the proposed COVID-19 VSC.

Mathematical model

The proposed mathematical model is formulated to obtain the optimal network decisions. Notations, objective function, and all constraints are presented in the following subsections:

Notations

The notations utilized to create the proposed model are listed below:

- \(\text{m}\epsilon \text{ M}\):

-

The HCs

- \(\text{j}\epsilon \text{J}\):

-

The DCs

- \(\text{i}\epsilon \text{I}\):

-

The candidate locations of CDCs

- \(\text{k}\epsilon \text{K}\):

-

Suppliers under Agreement A

- \(\text{l}\epsilon \text{L}\):

-

Suppliers under Agreement B

- \(\text{r}\epsilon \text{R}\):

-

The priority groups

- t\(\epsilon \text{T}\):

-

Periods

- \(\text{s}\epsilon \text{S}\):

-

Scenarios

- \({\text{fc}}_{\text{k}}\):

-

Fixed cost for agreement with supplier \(k\)

- \({\text{fc}{\prime}}_{\text{l}}\):

-

Fixed cost for agreement with supplier \(l\)

- \({\text{fc}"}_{\text{i}}\):

-

Fixed cost for establishing CDC \(i\)

- \({\text{tc}}_{\text{j}}\):

-

Transportation cost for delivering each vaccine from the MoH to the DC \(j\)

- \({\text{tc}{\prime}}_{\text{i}}\):

-

Transportation cost for delivering each vaccine from the MoH to the CDC \(i\)

- \({\text{tc}"}_{\text{m}}\):

-

Transportation cost for delivering each vaccine from the MoH to the HC \(m\)

- \({\text{tc}{\prime}{\prime}{\prime}}_{\text{ij}}\):

-

Transportation cost for delivering each vaccine from the CDC \(i\) to the DC \(j\)

- \({\text{tc}""}_{\text{im}}\):

-

Transportation cost for delivering each vaccine from the DC \(i\) to the HC \(m\)

- \({\widetilde{\text{pr}}}_{\text{k}}\):

-

Price of each vaccine vial supplied by supplier \(k\) as a trapezoidal fuzzy number (\({\widetilde{pr}}_{k}={pr}_{k}^{1},{pr}_{k}^{2},{pr}_{k}^{3}, {pr}_{k}^{4}\))

- \({\widetilde{\text{pr}}}_{\text{l}}{\prime}\):

-

Price of each vaccine vial supplied by supplier \(l\) as a trapezoidal fuzzy number (\({\widetilde{pr}}_{l}{\prime}={pr}_{l}^{{\prime}1},{pr}_{l}^{{\prime}2},{pr}_{l}^{{\prime}3}, {pr}_{l}^{{\prime}4}\))

- \({\widetilde{\text{pr}}}_{\text{l}}^{"}\):

-

Price of each vaccine vial supplied by supplier \(l\) for the current period as a trapezoidal fuzzy number (\({\widetilde{pr}}_{l}^{"}={pr}_{l}^{"1},{pr}_{l}^{"2},{pr}_{l}^{"3}, {pr}_{l}^{"4}\))

- \(\widetilde{{\text{q}}_{\text{kt}}}\):

-

Quality level of supplier \(k\) in period \(t\) as a trapezoidal fuzzy number (\({\widetilde{q}}_{kt}={q}_{kt}^{1},{q}_{kt}^{2},{q}_{kt}^{3}, {q}_{kt}^{4}\))

- \(\widetilde{{\text{q}{\prime}}_{\text{lt}}}\):

-

Quality level of supplier \(l\) in period \(t\) as a trapezoidal fuzzy number (\({\widetilde{q}}_{lt}{\prime}={q}_{lt}^{{\prime}1},{q}_{lt}^{{\prime}2},{q}_{lt}^{{\prime}3}, {q}_{lt}^{{\prime}4}\))

- \({\text{n}}_{\text{kts}}\):

-

Number of vaccines supplied by supplier \(k\) in period \(t\) under scenario \(\text{s}\)

- \({\text{n}{\prime}}_{\text{lts}}\):

-

Number of vaccines supplied by supplier \(l\) in period \(t\) under scenario \(\text{s}\)

- \({\text{d}}_{\text{mr}}\):

-

Vaccine demand for priority group \(r\) in the HC \(m\)

- \({\upomega }_{\text{r}}\):

-

Weight associated with each unmet demand in priority group \(r\)

- \({\upomega {\prime}}_{\text{m}}\):

-

Weight of population density around the HC \(m\)

- \({\text{sc}}_{\text{r}}\):

-

Social cost of each unmet demand in priority group \(r\)

- \({\text{dc}}_{\text{m}}\):

-

Penalty cost of the unvaccinated population around the HC \(m\)

- \({\text{cap}}_{\text{m}}\):

-

Capacity of the HC \(m\)

- \({\text{dis}}_{\text{j}}\):

-

Distance between the MoH and the DC \(j\)

- \({\text{dis}^{\prime}}_{\text{i}}\):

-

Distance between the MoH and CDC \(i\)

- \({\text{dis}"}_{\text{m}}\):

-

Distance between the MoH and the HC \(m\)

- \({\text{dis}^{\prime\prime\prime}}_{\text{ij}}\):

-

Distance between the CDC \(i\) and the DC \(j\)

- \({\text{dis}""}_{\text{jm}}\):

-

Distance between the DC \(j\) and the HC \(m\)

- \({\text{n}}^{\text{min}}\):

-

A minimum number of vaccines can be supplied by supplier \(k\)

- \({\text{n}}^{{^{\prime}}\text{min}}\):

-

A minimum number of vaccines can be supplied by supplier \(l\)

- \({\text{q}}^{\text{min}}\):

-

Minimum acceptable quality level of vaccines

- \({\text{p}}_{\text{s}}\):

-

Probability of occurring scenario \(s\)

- \(\text{B}\):

-

A large positive value

- \({\text{y}}_{\text{kts}}\):

-

Number of supplied vaccines by supplier \(k\) for the next period of \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{y}^{\prime}}_{\text{lts}}\):

-

Number of supplied vaccines by supplier \(l\) for the next period of \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{y}"}_{\text{lts}}\):

-

Number of supplied vaccines by supplier \(l\) for the current period \(t\) under scenario s

- \({\text{x}}_{\text{jts}}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the MoH to the DC \(j\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{x}^{\prime}}_{\text{its}}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the MoH to the CDC \(i\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{x}"}_{\text{mrts}}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the MoH to the HC \(m\) for priority group \(r\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{x}^{\prime\prime\prime}}_{\text{ijts}}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the CDC \(i\) to the DC \(j\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{x}""}_{\text{jmrts}}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the DC \(j\) to the HC \(m\) for priority group \(r\) in period \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{u}}_{\text{mrts}}\):

-

Number of unmet demands from the priority group \(r\) around the HC \(m\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\)

- \({\text{Z}}_{\text{i}}\):

-

1, If the CDC \(i\) is activated; 0, otherwise

- \({\text{O}}_{\text{kts}}\):

-

1, If supplier \(k\) is selected in period \(t\) under scenario \(s\); 0, otherwise

- \({\text{O}^{\prime}}_{\text{lts}}\):

-

1, If supplier \(l\) is selected in period \(t\) under scenario \(\text{s}\); 0, otherwise

- \({\text{A}}_{\text{jts}}\):

-

1, If the MoH is allocated to the DC \(j\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\); 0, otherwise

- \({\text{A}^{\prime}}_{\text{its}}\):

-

1, If the MoH is allocated to the CDC \(i\) in period \(t\) under scenario \(s\); 0, otherwise

- \({\text{A}"}_{\text{mts}}\):

-

1, If the MoH is allocated to the HC \(m\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s\); 0, otherwise

- \({\text{A}^{\prime\prime\prime}}_{\text{ijts}}\):

-

1, If the CDC \(i\) is allocated to the DC \(j\) in period \(t\) under scenario \(s\), 0 otherwise

- \({\text{A}""}_{\text{jmts}}\):

-

1, If the DC \(j\) is allocated to the HC \(m\) in period \(t\) under scenario \(s\), 0 otherwise

Objective function

We use the standard procedure of optimization modeling to develop the optimization model using the provided notations, as follows:

Equation (1) presents the objective function consisting of four main terms minimizing the total cost of the network. The first term is the first-stage costs according to MSSP minimizes the establishment cost of CDCs, and the other terms compute the next stages. The second term is the vaccine purchase costs including the suppliers’ agreement cost and vaccine’s purchasing costs. The third term presents the transportation cost between different centers at all channels (i.e., from MoH to CDCs, MoH to DCs, MoH to HCs, CDCs to DCs, and DCs to HCs, respectively). The last component is the residual risk of complications from the epidemic situations which is the social cost of unvaccinated people. In order to prioritize vaccine allocation, two issues are considered the most at-risk communities and crowded areas that would be the best candidates for sooner vaccination. The proposed model includes the following constraints:

Limitations in the vaccine orders

The range of vaccine quantities that each supplier is capable of producing and delivering is considered as follows:

Constraints (2) and (3) specify the minimum and maximum quantities of vaccines that can be manufactured and supplied by each supplier during each period.

Limitations in the quality of vaccines

The supplier must satisfy the requirements outlined in the constraints to be considered for selection.

Constraints (4) and (5) imply that a supplier can only be selected if it meets the minimum qualifications specified.

Equations of flow balance

Flow balance is a critical aspect of the supply chain, as it ensures that resources are allocated efficiently and that there are no bottlenecks or imbalances in the system.

Equations (6) to (8) are indicative of flow balance within different channels. Equation (6) ensures that the inflows and outflows to the MoH are equal, while subsequent constraints guarantee the same for each CDC and each DC. This means that the optimization model is designed to maintain flow balance throughout the network, ensuring that the number of vaccines entering and leaving each location is equal.

Equations of Unmet demand

Equations (9) and (10) are utilized to compute the number of unvaccinated individuals in each period.

Limitations in HCs’ capacity

Constraint (11) indicates that the capacity of each HC is limited.

Limitation in selected channel

Equation (12) guarantees the selection of a single channel for vaccine allocation per HC, ensuring that each assigned HC has only one supply point. Besides, Constraint (13) ensures that each DC is allocated to a single channel, and if the economic channel is chosen, it is assigned to only one CDC.

Constraints of location and allocation

The following constraints play a critical role in governing the movement of vaccines within the supply chain, ensuring that vaccines are appropriately distributed between different levels of the VSC network and that the flow of vaccines aligns with the operational status of the facilities involved.

The purpose of Constraint (14) in the VSC is to demonstrate that vaccine flow occurs between the MoH and a CDC when that CDC is opened. On the other hand, Constraints (15) to (19) indicate that vaccine flow happens between two echelons when a facility is allocated to another of them. Finally, the type of variables is illustrated as follows:

Constraints (20) and (21) specify the different types of decision variables.

Solution methodology

In this section, solution methodologies including the multi-stage approach to dealing with stochastic supply and fuzzy programming to face fuzzy price and quality of vaccines are presented.

Multi-stage stochastic programming

The stochastic programming technique is widely used in various scopes such as finance, transportation, and energy optimization because of the prevalence of uncertainty in real-world decisions. It involves making optimal decisions based on available data at the time the decisions are made, without depending on future observations. The Two-Stage Stochastic Programming (TSSP) is a common approach, where the first-stage decisions are made at the beginning of the period, followed by the resolution of uncertainty, and the second-stage decisions are taken as corrective action at the end of the period. Stochastic programming is particularly useful for problems with a hierarchical framework, such as scheduling. The approach involves a combination of proactive and reactive decision-making to address uncertainty, where the second-stage variables respond reactively to the observed realization of uncertainty. The classical two-stage stochastic linear program with fixed recourse is a commonly used formulation for such problems. In summary, stochastic programming models, particularly MSSP, provide a powerful framework for decision-making under uncertainty, with applications in a wide range of industries and domains.

A stochastic programming model is a method used to optimize under uncertain conditions. It aims to find a solution that takes into account the uncertainty of problem parameters and optimizes goals selected by DMs. In general, an MSSP model with \(K\)-stages consists of several stochastic parameters named \({\upgamma }_{1}, {\upgamma }_{2} ,\dots , {\upgamma }_{\aleph -1}\), with each of them having realizations as scenarios. A scenario tree is used to integrate these separate scenarios, and the scenario probabilities are denoted as \({p}_{1}, {p}_{2} ,\dots , {p}_{s}\). A realization of stochastic parameters for scenario \(s\epsilon S\) is demonstrated by \(({\upgamma }_{1}^{s}, {\upgamma }_{2}^{s}, \dots , {\upgamma }_{\aleph -1}^{s}\)). In Fig. 2, a stochastic program with four stages \(\aleph =4\) and three periods \(t=3\) is typically represented as a sample of a scenario tree.

In an MSSP model, strategic decisions such as facility location and construction are made at the beginning and remain fixed in subsequent stages. Tactical decisions such as selection and allocation decisions must also be made before the realization of stochastic parameters, but they can be changed in each period. Operational decisions such as the flow between facilities are made when the stochastic parameters are realized at each stage. In summary, MSSP models involve making proactive–reactive decisions to address uncertainty, with the first-stage decisions being made based on available data, and the second-stage decisions being reactive to the observed realization of uncertainty.

In an MSSP model, the decision-making process should not be influenced by how stochastic parameters will be realized in the future. This means that the policy should not be anticipative, and non-anticaptivity constraints are imposed to formulate an MSSP model. By applying non-anticaptivity constraints, a public formulation for an MSSP including \(\aleph\)-stage can be introduced. To ensure that decisions are not influenced by future information, non-anticaptivity constraints must be incorporated into the optimization model of MSSP. These constraints guarantee that decision variables across different scenarios are equal, thereby preventing the anticipation of uncertain parameter values that are yet to be realized.

The decision vector for stages \(\aleph \epsilon \{\text{1,2},\dots ,\aleph \}\) and scenarios \(s\epsilon S\) is represented by \({x}^{\aleph s}\), with stochastic parameters being realized only after decisions are made at each stage. In the first stage of the scenario tree, the equation \({x}^{\aleph s}={x}^{\aleph {s}^{{{\prime}}}}\) applies to every pair of scenarios; \(s,{s}^{{{\prime}}}\epsilon S\). Additionally, for every stage \(\aleph >1\) and scenario \(s,{s}^{{{\prime}}}\epsilon S\) such that \(\left({\upgamma }_{1}^{s}, {\upgamma }_{2}^{s}, \dots , {\upgamma }_{\aleph -1}^{s}\right)=\left({\upgamma }_{1}^{{s}^{{{\prime}}}}, {\upgamma }_{2}^{{s}^{{{\prime}}}}, \dots , {\upgamma }_{\aleph -1}^{{s}^{{{\prime}}}}\right)\), we have \({x}^{\aleph s}={x}^{\aleph {s}^{{\prime}}}\). The feasible range of DMs at stage \(\aleph\) and scenario \(s\) in the MSSP is determined by \({X}^{\aleph s}\) as follows:

Developing a stochastic program based on scenarios presents a significant challenge in creating an efficient scenario tree after reducing the scenarios to represent stochastic parameters separately. Initially, the Monte Carlo simulation algorithm is utilized to generate a set of discrete scenarios for building a scenario tree. However, the large number of scenarios can render the problem unsolvable. This heuristic approach involves two methods for reducing backward and forward scenarios. In the backward algorithm, scenarios are eliminated one by one, while in the forward approach, scenarios are optimally selected one by one. Subsequently, the approach proposed by Heitsch and Romisch 54 is used to convert the scenario fan to a scenario tree, employing forward and backward algorithms for scenario reduction. Notably, a forward algorithm is used in each period to reduce the scenario and convert the scenario fan into a scenario tree. This process is essential for effectively managing the complexity of the scenario tree and ensuring that it accurately represents the stochastic parameters in the multistage stochastic program.

The non-anticipative constraints for the proposed model are as follows:

The supplier selection (\(O , O{^{\prime}}\)) and allocation (\(A\), \(A{\prime}\), \(A"\), \(A{\prime}{\prime}{\prime}\), \(A""\)) decisions should be determined before the realization of uncertain inputs at each stage of the MSSP. Therefore, Constraints (26)–(39) illustrate the non-anticaptivity constraints of the MSSP.

In this study, the representation of uncertain parameters in period \(t\) under scenario \(s\) is denoted by \({\upgamma }_{\text{t}}^{s}\). The decision variables \({y}_{kts}, {y}_{lts}{\prime}, {y"}_{lts},{x}_{jts},{x{\prime}}_{its},{x"}_{mrts},{x{\prime}{\prime}{\prime}}_{ijts},{x""}_{jmrts}, and {u}_{mrts}\) are utilized. Equations (40) to (48) ensure that these variables adhere to non-anticipative constraints, preventing them from being influenced by future information.

Fuzzy mathematical programming

Fuzzy programming is a useful approach for addressing uncertainty in parameters and providing necessity in model mechanisms. Two main modules of fuzzy mathematical programming, possibility and necessity are proposed by Inuiguchi and Ramk 55 and Mula et al. 56, respectively. The possibility is utilized when an input parameter is uncertain or insufficient because of a lack of required data, involving the establishment of a distribution for each uncertain parameter according to the subjective opinions of DMs and objective data. Conversely, necessity can accommodate resistance to constraints, equations, and the adaptability of functions.

Possibility chance-constrained programming is a useful method in possibility programming that deals with probabilistic data in uncertain situations. This method allows the DM to set an optimum confidence level (\(\partial\)) to satisfy each possibility chance constraint, using possibility (\(POS\)) and necessity (\(NEC\)) as fuzzy measure standards to give confidence in models 57. The standards mentioned represent the most pessimistic and optimistic levels of the possibility of input occurrence. Equations (50)–(53) for \(\partial\) ≥0.5 are the crisp counterparts of the standards for a trapezoidal fuzzy variable. Additionally, Eq. (49) illustrates the corresponding membership function, where \(\widetilde{\mathcal{E}}=({\varepsilon }_{1},{\varepsilon }_{2}, {\varepsilon }_{3},{\varepsilon }_{4})\) with \({\varepsilon }_{1}<{\varepsilon }_{2}<{\varepsilon }_{3}<{\varepsilon }_{4}\). It is noteworthy that when \({\varepsilon }_{2}={\varepsilon }_{3}\), a triangular fuzzy variable is made from some changes in the trapezoidal one. Furthermore, based on Liu and Liu 58, Eqs. (54) and (55) show the expected value of the variable.

In real-world conditions, DMs often exhibit fluctuating behavior between pessimistic and optimistic conditions. Equation (56) introduces a self-dual credibility (\(CRE\)) measure developed 58, which inspires a compromising attitude of DMs over both pessimistic and optimistic conditions. Furthermore, Eqs. (57)–(59) determine credibility criteria for confidence levels \(\partial\)≥0.5. Additionally, the expected value of the trapezoidal fuzzy variable for \({\varepsilon }_{1}\ge\) 0 is presented by Eq. (59).

The previous approach of using a midpoint to avoid extreme decisions may not be flexible enough for DMs. Xu and Zhou 59 proposed an alternative approach called the \(Me\) measure, which is a fuzzy number that is both flexible and avoids extreme decision-making. The approach described allows DMs to select a point from a spectrum of feasible alternatives based on real-life conditions using parameter settings in Eq. (60). In this method, \(\tau (0\le \tau \le 1)\) serves as a flexible criterion that enables DMs to make decisions reflecting real-life situations. For \(\tau\)=1, the maximum chance that the possibility (i.e., the most optimistic attitude) occurs, resulting in \(Me=POS\). Similarly, for \(\tau\)=0, the minimum chance that the possibility occurs, leading to \(Me=NEC\). For \(\tau\)=0.5, the \(\text{Me}=\text{CRE}\) C, which represents a compromising attitude of DMs. Equations (61), (62) demonstrate the \(Me\) measure, while Eq. (63) denotes the expected value of the trapezoidal fuzzy variable for \({\varepsilon }_{1}\ge 0\) based on the \(Me\) measure 59.

The \(Me\) measure, unlike previous mechanisms, does not equate \(Me\) \(\left\{\widetilde{\mathcal{E}}\le \mathcal{x}\right\}\)≥ \(\partial\) and \(Me\) \(\left\{\widetilde{\mathcal{E}}\le \mathcal{x}\right\}\)≥\(\partial\) for different confidence levels. Instead, it involves piecewise functions. DMs often use this approach in problems with high sensitivity to uncertain parameters to achieve possibility chance constraints while upholding an extremely reasonable chance. In sensitive scenarios such as health supply chain design, DMs often adopt a pessimistic approach. This implies that in these situations, they consider the pessimistic-optimistic parameter value to be less than 0.5. Representing the pessimistic method, the functions are akin to those depicted in Eqs. (64), (65).

Blockchain technology consideration

In 2008, Nakamoto 60 introduced blockchain technology as a way to support transactions in the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Blockchain is a decentralized, transparent, and secure platform where transactions between connected parties are recorded and stored on all participating computers, ensuring the data remains unchanged. While blockchain originated in the cryptocurrency field, it has since been explored and implemented across various industries. One notable example is the Smart Dubai 2021 project, which saw the integration of blockchain technology into government operations 61. SCM is one of the fields that has shown particular interest in blockchain technology. Researchers predict that blockchain will revolutionize supply chains by increasing the reliance on this innovative technology 62. Recent studies have explored the application of blockchain in diverse supply chain scenarios, such as the drug, food, healthcare, and research and development industries.

Platforms based on blockchains involve multiple components that work together. By combining them, blockchain renders contracted items to connected people (Fig. 3).

Following the widespread COVID-19 outbreak and the success of various companies in vaccine production, the primary challenge for countries is to supply high-quality vaccines and plan for a seamless vaccination process. Some of the key challenges faced by countries in this context include:

-

I.

The limited supply and urgent global demand for vaccines in the COVID-19 epidemic have increased the likelihood of theft and fraud in the supply chain.

-

II.

Ensuring the quality of vaccines is a critical issue, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic when the global demand for vaccines is high and the supply is limited. Quality control of purchased vaccines is an effective way to select suppliers and ensure that vaccines consistently meet appropriate levels of purity, potency, safety, and efficacy.

-

III.

In an epidemic situation, it is crucial to avoid congestion to ensure efficient and safe vaccine distribution. To achieve this, careful planning and prioritization of vaccinations are essential. Additionally, transparency and traceability of orders can help in careful planning and resource allocation.

-

IV.

Vaccines are perishable products that must be transported and saved under specific temperature conditions within the cold chain. The cold chain is a temperature-controlled system that includes all vaccine-related equipment and methods, ensuring that vaccines maintain their potency and effectiveness.

When evaluating the integration of blockchain technology across all components of the VSC network, as illustrated in Fig. 4, it is necessary to strike a tradeoff between cost and transparency. While blockchain offers enhanced security and transparency benefits, implementing it extensively can lead to a rise in installation costs. Therefore, a strategic approach is necessary to weigh the advantages of blockchain against the associated costs, ensuring a judicious trade-off between cost-effectiveness and the benefits of enhanced security and transparency. In the next subsection, we design a blockchain-enabled COVID-19 VSC network under epidemic conditions to consider the mentioned risks and transparency.

This research proposes a supply chain network for COVID-19 vaccines that uses blockchain and IoT. IoT is utilized for monitoring the storage conditions of vaccines, including factors such as temperature and humidity, to ensure their integrity during transportation and storage. By deploying IoT sensors on vaccine shipments and leveraging blockchain smart contracts, organizations can gain visibility into the COVID-19 VSC, confirm product arrival, and monitor the quality of vaccines during transportation and storage. These technologies can significantly enhance the efficiency, security, and transparency of the VSC network design.

The aim is to merge the blockchain concept with the VSC to establish a blockchain-enabled multi-level VSC network. This supply chain configuration comprises five echelons: suppliers, MoH, CDCs, DCs, and HCs. Transparency serves as the key objective function in this setup. To facilitate this integration, CDCs and vehicles are equipped with IoT devices, enabling the conversion of the physical flow within the supply chain into a digital flow, thereby generating blocks. To create a blockchain, at least one member from the preceding level and one member from the next level must be linked to the equipped member. The blockchain concept is inherently decentralized, and the more blocks generated by the equipped CDCs, the greater the transparency achieved. The transparency criterion is based on the probability that an attacker will not succeed in manipulating the blockchain, as proposed by previous studies 63. The CDCs incur costs associated with being equipped with IoT tools to create the blockchain infrastructure and provide services to other levels. This cost is considered a proportion of the installation costs for that particular member. Members who join the blockchain will benefit from advantages such as transparency, tracking, better planning, and security. These benefits can lead to cost savings, and a portion of these savings can be factored in as revenue in the supply chain. Given that the members of the blockchain must negotiate the benefits, and these benefits are interactive between the members, they are treated as a factor of the cost of interactions between levels, such as transportation costs. The related notations and the integrated VSC and blockchain are as follows:

- \(\mathcal{b}\in \mathcal{B}\):

-

Index of generated blocks in the VSC network

- \({\mathcal{c}\mathcal{f}}_{i\mathcal{b}}^{p}\):

-

The assessment of the attacker’s advancement in terms of their lack of success, determined by the block type \(\mathcal{b}\) produced in CDC \(i\)

- \({\mathcal{T}}_{i}^{A}\):

-

Blockchain technology adoption parameter in CDC \(i\) to create transparency in the VSC

- \({\mathcal{t}}^{min},{\mathcal{t}}^{max}\):

-

Minimum and maximum values of transparency

- \({\mathcal{c}\mathcal{r}}^{min}\):

-

Minimum number of CDCs participating in the blockchain

- \(\partial\):

-

The ratio of the variable installation cost to the expense associated with utilizing blockchain technology

- \({\ell}\):

-

The ratio of the variable transportation cost to the expense associated with utilizing blockchain technology

- \({\mathcal{n}}_{i\mathcal{b}}\):

-

Equal to 1 If block type \(\mathcal{b}\) is installed in CDC \(i\), equal to 0

- \({\mathcal{C}}_{i}\):

-

Equal to 1 If CDC \(i\) is equipped with an IoT tool, equal to 0

- \({\mathcal{C}\mathcal{M}}_{i}^{1\to 2}\):

-

Equal to 1 if CDC \(i\) and the MoH participate to form the blockchain, equal to 0

- \({\mathcal{C}\mathcal{D}}_{ij}^{2\to 3}\):

-

Equal to 1 if CDC \(i\) and the DC \(j\) participate to form the blockchain, equal to 0

- \({x}_{its}^{{\prime}1\to 2}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the MoH to the CDC \(i\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s;\)

- \({x}_{ijts}^{{\prime}{\prime}{\prime}2\to 3}\):

-

Number of transported vaccines from the CDC \(i\) to the DC \(j\) at period \(t\) under scenario \(s;\)

The primary goal of the initial Objective Function (66) is to maximize the overall number of extracted blocks in the equipped CDCs, fostering decentralization within the network. Conversely, in scenarios where an attacker seeks to tamper with blockchain data, their advancement in terms of failure, represented by the parameter \({\mathcal{c}\mathcal{f}}_{i\mathcal{b}}^{p}\) during attacks, is derived by aggregating the negative binomial distribution at each attack stage. As the quantity of blocks (\(\mathcal{b}\)) increases, the failure progression escalates due to the cumulative effect of additional distributions linked to the block count. Consequently, the attacker’s likelihood of success diminishes significantly with higher values of \(\mathcal{b}\) in the equipped CDCs. The second Objective Function (67) focuses on optimizing the financial aspects of the supply chain by minimizing operational costs.

Constraint (68) stipulates that block production is contingent upon the installation of CDC. Constraints (69) and (70) ensure that for CDC \(i\) to be part of the blockchain, there must be representation from both levels of the VSC. Constraints (71) and (72) elucidate that blockchain formation necessitates physical flow between different supply chain levels. Constraints (73) and (74) signify that equipping CDC \(i\) with an IoT tool is essential for block production within the blockchain. Constraint (75) sets the transparency thresholds expected from the supply chain manager. To promote decentralization, Constraint (76) guarantees a minimum number of independent CDCs within the blockchain. Constraints (77) and (78) define the total count of independent blocks generated in the CDCs. Constraint (79) outlines the binary decision variables.

Case study

Iran experienced a rapid spread of COVID-19 shortly after it was first recognized in China in December 2019. The MoH and Medical Education of Iran officially reported the first cases of COVID-19 in Qom province on February 19, 2020. Since the outbreak began, Iran has introduced the highest number of COVID-19 cases in the Middle East. In addition, according to the report of the MoH Iran on April 10, 2021, most cities of this country are classified as high-risk areas as shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, Fig. 6 shows that government measures to combat this infectious disease have not been successful in Iran. The reports indicate that by November 21, 2023, 7.623 million cases have been infected with COVID-19, and some 146,633 patients have died.

Density of COVID-19 outbreak cases in Iran (www.tasnimnews.com).

The success of pharmacists in producing the COVID-19 vaccine has highlighted vaccination as the most effective method to eradicate the novel coronavirus. In Iran, the vast area and population size have posed significant challenges to vaccine supply and distribution. Therefore, it is crucial to design an efficient distribution network for the country. Several works have highlighted the importance of vaccination and the need for an optimized VSC during the COVID-19 epidemic, particularly in countries with large populations like Iran. The Iranian government considers the selection of vaccine suppliers to be crucial. While foreign manufacturers have produced a limited number of high-quality vaccines, the political situation in Iran has complicated this issue. Concurrently, several domestic pharmaceutical institutes in Iran have initiated vaccine development efforts since the identification of COVID-19. Although three domestic producers have successfully developed vaccines, their production capacity is constrained. Some domestic suppliers and certain foreign companies can offer immediate supply, while others need to consider lead time. Table A.1 in Appendix A presents an overview of the features of the suppliers intended to fulfill the order.

As previously mentioned, a significant challenge for countries is ensuring equitable vaccine distribution to address the urgent needs of society. To address this, clustering algorithms can be utilized to prioritize areas and age groups for vaccination. In Iran, the heterogeneous population density has influenced the prioritization policy for vaccine allocation as shown in Fig. 7. The country has been divided into four priority groups based on population density, aiming to vaccinate densely populated areas first. Additionally, the population has been classified into four categories to prioritize age groups, with recent research highlighting the heightened risk among the elderly age group. This approach aims to ensure a fair and efficient distribution of vaccines in Iran.

Population density in Iran (https://popdensitymap.ucoz.ru).

In the analyzed network, four main types of facilities have been identified. The distribution network begins at Iran’s MoH warehouses. Additionally, the network includes 4 CDCs and 10 DCs. Given the numerous HCs in Iran, a clustering algorithm was employed to group similar cases in each region, resulting in the identification of 52 HCs. A map displaying the geographical distribution of proposed network facilities is presented in Fig. 8, while Tables A.2 to A.5 in Appendix A demonstrate the characteristics of these facilities. To calculate the distance traveled between the two centers, the following great circle formula is used using their geographical coordinates. It is important to note that the geographic coordinates in the formula should be in radians.

Geographic dispersion of facilities and suppliers in the case study of Iran (our data based on Iran map in http://browse.ir).

Implementation and results

In this part, we apply the real case study presented in Section "Implementation and Results" to validate and analyze the proposed model and methodology. The software used in the study is GAMS version 23.5.2, and the URL for the documentation related to this version can be found at https://www.gams.com/latest/docs/RN_235.html. We use this software by CPLEX solver on a personal computer with Intel Core i5, CPU 2.4GHz, and 8GB of RAM for all implementations. In the first phase, optimal vaccine supplier selection is specified. Then, in the next phase, the vaccine distribution model is employed for designing the vaccine allocation network under uncertainties.

As we mentioned in Section "Solution methodology", the number of vaccines supplied by each supplier is a stochastic parameter. To determine the vaccine supplied by each supplier in each period, 2520 scenarios are generated, and the scenarios are reduced to the scenario fan becomes a scenario tree (Fig. 9). The obtained scenario tree contains 11 scenarios, 39 nodes, and 6 stages which is shown in Fig. 10. According to WHO, vaccine production by introduced suppliers will increase during the next months. On the other hand, the number of vaccines provided by each supplier is uncertain, which is determined according to the scenario tree generated for different periods and scenarios.

As aforementioned, a scenario fan of the supply is transformed into a scenario tree. Hence, a fan covering 2520 scenarios is generated by the Monte Carlo simulation approach. Then, we decrease the number of scenarios to 11 and nodes to 39 by the scenario reduction approach and transform them into the scenario tree. The probabilities of 39 nodes are presented in Table 2. Eventually, 11 scenarios remain in the scenario tree, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The fixed costs are utilized for the establishment of CDCs to compute them along with other costs. Consequently, the values of \({Z}_{i}\) are identical, amounting to 2000 dollars for each CDC. The varying popularity of each vaccine type among individuals and the risk of shortage lead to distinct shortage costs for each type and group of people.

Table 3 demonstrates the number of vaccines produced by suppliers in different periods and scenarios. The simulation results show that all CDCs are open, which means the number of vaccines can be transported quickly. It can be understood from Table 3 that Moderna (3) and Shionogi (4) suppliers have supplied the COVID-19 vaccines in different periods and scenarios according to Agreement A. In addition, no vaccine was provided in the first periods one and two in this agreement type for Moderna (3). It can be inferred from these results that optimal vaccine supplier selection is specified as COVIran Barekat (1) and Razi (2) suppliers of COVID-19 vaccines in all periods and scenarios according to Agreement B.

Figure 11 shows that the summation of the vaccines supplied by Agreement A which can only supply for the next period is lesser than Agreement B which can provide for the current period but at a higher price. The most and least number of vaccines are provided by COVIran Barekat (1) and Moderna (3) suppliers, respectively.

In another point of analysis, Fig. 12 demonstrates the number of vaccines supplied by different suppliers in each period and different scenarios. As you can see, the last period has the most values of vaccine supplied. Also, over time, suppliers have become more capable of responding to the demands of vaccines which means suppliers have adapted to the demands of vaccine production. These adaptations have been crucial in meeting the unprecedented demand for COVID-19 vaccines and ensuring their equitable distribution.

To show the results more clearly, we consider only the first period and the first scenario and depict the optimal decision variables in Fig. 13. In this regard, all of the optimal results for different allocations and corresponding values are shown in this figure. In part (A) allocations of suppliers to MoH, MoH to CDCs, and MoH to DCs, in part (B) allocations of MoH to HCs, and in part (C) allocation of CDCs to DCs are reported. In addition, decision variables related to the assignment of DCs to HCs are given in Table 4 in detail. Note that the model can prioritize people, in which the priority group first receives vaccines from the HCs. After that, the rest of the COVID-19 vaccines are assigned to the next priority group, the third group, and finally, the fourth group.

The comparison of vaccine units delivered to different groups of people in HCs is examined in Table 5 under two modes including considering priority and without priority setting.

The table demonstrates that the allocated vaccines to the high-risk group increase when the priority approach is applied. Hence, the assigned vaccines to the low-risk group (groups 3 and 4) equals zero. For instance, in scenario 1, considering the priority, the assigned vaccines to the first and second groups are 7.62205E + 7 and 1.76744E + 8, respectively, while the third and fourth groups receive zero. In contrast, without considering priority, 1.17138E + 7, 6.02863E + 7, 4.38275E + 7, and 1.64997E + 7 are assigned to the first to fourth groups, respectively. These findings are demonstrated in Fig. 14. Because the vaccines for groups 3 and 4 are given zero considering priority and the analysis is clear, only the schematic comparison of the first two groups is sufficient. Generally, these results indicate that when prioritization is implemented, the groups with higher priority are addressed first, leading to a deficiency in responding to the two groups with lower priority. This deficiency arises when priority is not assigned to all four groups due to other limitations of the vaccine specialization model.

Here, we analyze the effects of fuzzy parameters on the value of the objective function, average shortage in each scenario, and CPU time. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis of \(\partial\) and \(\tau\) values is presented in Table 6. As mentioned earlier, the DM can use an optimum confidence level (\(\partial\)) to satisfy each possibility chance constraint. Additionally, \(\tau (0\le \tau \le 1)\) is a flexible index that DMs can make decisions according to real-life conditions.

To conduct a simpler sensitivity analysis, Fig. 15 shows the grid of scatterplots that enables us to explore bivariate relationships.

As you can see in Fig. 15, the relationships between \(\tau\) and objective function, and \(\tau\) and average of shortage are decreasing. Besides, \(\partial\) has a direct relationship with the objective function and average of shortage. Next, sensitivity analysis is conducted to check the quality parameters in the presented model. In this respect, Table 7 reports these results in detail. For convenience, Fig. 16 visualizes the achieved values with a fit to a smooth nonparametric bivariate surface using a set of contours in 5% intervals. These intervals partly help cover more problem instances. From Table 7 and Fig. 16, it can be understood that with the increase of the parameter \({qu"}_{min}\), objective function and average shortage in each scenario also increase.

Afterward, sensitivity analysis is conducted to check the price of vaccine parameters in the proposed model similarly. In this regard, Table 8 gives the average vaccines for each agreement in terms of fuzzy values of vaccine price. As expected, as the cost of each type of vaccine decreases, the average total number of supplied vaccines increases; conversely, with an increase in costs, the number decreases. Generally, price changes can affect supplier selection in various ways, such as supplier profitability, competitive advantage, supplier evaluation, and total cost. Understanding these impacts can help both government and suppliers make informed decisions when selecting and working with suppliers.

Here, the outcomes of the model are presented using the MSSP and compared with TSSP. A metric, known as the Relative Value (RV) of MSSP, to assess the significance of MSSP and TSSP models introduced by Huang and Ahmed 64. RV in a stochastic optimization problem is according to Eq. (81):

In which \({F}^{MSSP}\) and \({F}^{TSSP}\) are the functions for the MSSP and TSSP models, respectively. Here, the non-anticaptivity constraints are given in Section "Multi-stage stochastic programming". Note that, the decisions related to the location of CDCs, allocation of MoH to DCs, MoH to CDCs, MoH to HCs, DCs to HCs, and CDCs to DCs for each period should be made at the start of the planning horizon in the TSSP approach. This means these decisions are independent of uncertain data. The optimal objective function values of the MSSP and TSSP models are given in Table 9. The RV value, which is obtained using Eq. (81) and equals 1.032, indicates that the MSSP model significantly reduces the objective function value compared to the TSSP model. Therefore, it can be inferred that handling the MSSP model leads to a significant improvement, as shown in Table 9.

This part provides some problem instances and a detailed discussion of sensitivity analyses on several important parameters. The model runs in reasonable times (138 s) with Gap %0, and the sensitivity analysis is done not much than 146 min. The use of algorithms to solve the proposed model for VSC networks and data is not necessary, and the model is suitable for large-scale problems. In this respect, five problem numerical examples with different sizes and settings are generated to survey the limit of the presented model. The sets of these instances, including the suppliers with Agreements A and B, DCs, potential CDCs, HCs, and priority, are illustrated in Table 10. The maximum allowable time limit for solving the model is set at 15 h, beyond which no solution is found, such for instance 5, within this timeframe. The findings indicate that while the computational time increases with larger problem instances, the proposed model successfully solves small and medium-sized problems.

The findings are significant for supply chain managers, as increasing transparency is a key objective to address the growing sophistication of attackers. To generate blocks, CDCs must be equipped with IoT devices that can convert physical flow into digital blocks. In the study, a fee proportional to the installation cost is considered for this equipment. Other members of the supply chain benefit from being connected to the blockchain network, such as improved tracking, transparency, security, and planning. Consequently, these members are willing to share a portion of these benefits with the equipped CDC.

Table 11 indicates that altering the conversion factors for installation and transportation in the proposed network has specific effects. Increasing the factor for equipping CDCs with IoT technology leads to a rise in costs while reducing the transportation factor also results in increased costs.

Figure 17 illustrates the interplay between the importance of different objective functions. By increasing the weight given to the transparency function compared to the supply chain costs objective function, transparency levels rise. This is achieved by growing the number of blocks in more transparent CDCs, which are more expensive. However, this increased transparency comes at the cost of higher supply chain costs, which can potentially increase by up to 31.112%.

Table 12 compares the impact of full and partial participation of CDCs in blockchain technology in terms of transparency and cost. Allowing partial participation can significantly reduce costs, although this comes at the expense of decreased transparency. However, the reduction in transparency is less substantial than the cost savings achieved. Hence, for cost-sensitive managers, considering partial participation may be a suitable option. CDCs participating in the blockchain must validate block creation through a consensus mechanism. While expanding the network and increasing the number of nodes can enhance transparency, it also escalates resource and time consumption, posing scalability challenges for blockchain technology. This growth can lead to operational congestion and potential damage to the blockchain system.

The study distinguishes itself from previous research by concentrating on optimization models derived from operations research, diverging from the common exploration of blockchain adoption in networks and supply chains in the existing literature. These models enable the simultaneous design of the supply chain and incorporation of blockchain technology, establishing a mutual influence where the supply chain network impacts blockchain configuration and vice versa. This methodology empowers managers to understand the usefulness and advantages of the proposed models, especially recommended for embedding transparency during the design and planning phases. Unlike prior works that primarily focus on operations, this research delves into decision-making at both strategic and tactical levels, merging supply chain design with blockchain adoption. Therefore, when contemplating the integration of blockchain technology in the supply chain, managers must meticulously assess the unique characteristics of their supply chain and determine the appropriate decision-making level they are comfortable with.

Management implications

Management implications can help translate research findings into practical recommendations and strategies for improving VSC management. In this respect, the following management implications and suggestions can be made for this study:

-

Supply Chain Management: The COVID-19 epidemic has highlighted the importance of supply chain management in ensuring the availability of vaccines to the public. The study should emphasize the need for a resilient supply chain that can quickly resume operations and continue to provide vaccines to the public after disruptions.

-

Digital Technology Applications: The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital technologies in supply chain management. The study should consider the potential benefits of digital technologies, such as blockchain, IoT, and machine learning, in improving the transparency, security, and efficiency of the VSC.

-

Risk Management: The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the need for effective risk management in supply chain management. The study should consider the risks associated with the VSC, such as the uncertainty of vaccine supply and demand, and propose strategies for managing these risks.

-