Abstract

Corynespora cassiicola is a highly diverse fungal pathogen that commonly occurs in tropical, subtropical, and greenhouse environments worldwide. In this study, the isolates were identified as C. cassiicola, and the optimum growth and sporulation were studied. The phenotypic characteristics of C. cassiicola, concerning 950 different growth conditions, were tested using Biolog PM plates 1–10. In addition, the strain of C. cassiicola DWZ from tobacco hosts was sequenced for the using Illumina PE150 and Pacbio technologies. The host resistance of tobacco Yunyan 87 with different maturity levels was investigated. In addition, the resistance evaluation of 10 common tobacco varieties was investigated. The results showed that C. cassiicola metabolized 89.47% of the tested carbon source, 100% of the nitrogen source, 100% of the phosphorus source, and 97.14% of the sulfur source. It can adapt to a variety of different osmotic pressure and pH environments, and has good decarboxylase and deaminase activities. The optimum conditions for pathogen growth and sporulation were 25–30 °C, and the growth was better on AEA and OA medium. The total length of the genome was 45.9 Mbp, the GC content was 51.23%, and a total of 13,061 protein-coding genes, 202 non-coding RNAs and 2801 and repeat sequences were predicted. Mature leaves were more susceptible than proper mature and immature leaves, and the average diameter of diseased spots reached 17.74 mm at 12 days. None of the tested ten cultivars exhibited obvious resistance to Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco, whereby all disease spot diameters reached > 10 mm and > 30 mm when at 5 and 10 days after inoculation, respectively. The phenotypic characteristics, genomic analysis of C. cassiicola and the cultivar resistance assessment of this pathogen have increased our understanding of Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) is an economic crop widely planted in the world of which China accounts for nearly 40% of the global tobacco leaf production and 40% of the global tobacco consumption1. Tobacco is easily infected by pathogenic fungi and bacteria during every period of its growth and development2. The four primary diseases—brown spot, Corynespora leaf spot, wildfire and horn spot—often occur simultaneously during the field period, causing irreparable damage. Corynespora leaf spot caused by C. cassiicola is a worldwide disease that infects many economically important crops such as rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis)3, tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.)4, cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.)5, cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.)6, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.)7 and soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.)8. It has also been found in nematodes9, sponges10, and rare cases of human infection11. Tobacco leaves infected by this disease normally start from the middle and lower tobacco leaves, with dark green spots which are water-stain-like initially, gradually turning brown, and ultimately expanding or combining to form nearly round spots, in conjunction with irregular large spots12. Tobacco Corynespora leaf spot was first reported in Nigeria in 19737. In China, the disease has been reported in the Guizhou, Guangxi, and Jiangxi provinces. Corynespora cassiicola has a strong infectivity, a wide range of transmission routes, and mutates easily. Until now, there are still no effective control measures for Corynespora leaf spot in tobacco.

Corynespora cassiicola isolates exhibits a variety of different lifestyles, including endophyte13,14, saprophyte15,16, and necrotrophic pathogens17. It has been shown to have multiple pathogenic types without clear geographic and host boundaries18,19. In addition, C. cassiicola isolates in the same climate had great differences in fungal growth, sporulation and pathogenicity 20,21,22. Some basic biological characters of C. cassiicola from different hosts have been reported by previous studies. The optimum temperature for the growth and sporulation of C. cassiicola ranges between 28 and 30 °C. At relative humidity > 90%, the suitable temperature range for spore germination of the pathogen ranges between 15 °C and 35 °C, with optimum temperature ranging from 25 °C to 30 °C23,24,25. However, the biological characteristics related to the carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur requirements, osmotic pressure, and the pH of the pathogen are still unknown. These are essential factors affecting the growth of this species. The phenotypic microarray (PM) system (OmniLog) developed by Biolog (Hayward, CA, United States) is capable of simultaneously characterizing nearly 1,000 metabolic phenotypes26,27. PM systems have been used to analyze the phenotypes of many microorganisms, including Alternaria alternata28, Pseudomonas syringae29, Botrytis cineara30, Ralstonia solanacearum31, Phytophora parasicitica32. Moreover, comparing the metabolic profiles of these tobacco pathogens might provide insight into the mechanisms of the mix-infection of these diseases.

Genome sequencing is one of the important tools to study microorganisms. The third generation sequencing platform plays an indispensable role in genome analysis of microorganisms such as fungi33,34, bacteria35,36 and yeasts37 due to its extremely long sequencing read length and non-GC bias. The study of Chin et al., (2013) showed that the SMRT technology was used to assemble 16 microbial genomes, which were 99.99% consistent with the reference genome38. Brownl et al. 2014 also found that there was still some gap in the genome of Clostridium autoethanogenum assembled by the second-generation sequencing platform Illumina, while the third-generation sequencing platform Pacbio could solve this problem perfectly39. Similar results were reported by Schmid et al.40 in Nanopore MinION sequencer, the genome assembly of Pseudomonas koreensis P19E3 was completed for the first time40. Genome sequencing is an important tool for understanding the pathogenic mechanisms of microbial pathogens and can be used for phylogenetic analysis of the species41.

Planting resistant cultivars is an important measure for plant disease management. C. cassiicola is listed as a high-risk pathogen for disease management by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee42. Fungicide resistance to C. cassiicola has been elucidated in numerous crops, including cucumber43, papaya44, and tomato45. Currently, the breeding of varieties resistant to Corynespora Leaf Fall Disease of Hevea Rubber46,47 and Cucumber leaf spot48,49 has been focused. The reported methods for identification of cultivar resistance to Corynespora Leaf Fall Disease of Hevea Rubber primarily included cake puncture, spore fluid spot grafting, the toxin pathogenic method and the spore fluid spray method46. The reported methods for identification of resistance to cucumber target leaf spot comprised mainly of artificial inoculation at the seedling stage and an identification of toxin inoculation48,50. However in tobacco, cultivar resistance to Corynespora leaf spot is still unclear, and there is still a lack of methods to identify tobacco resistance to C. cassiicola.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were: (i) to investigate the basic biological characteristics and metabolic phenotype of C. cassiicola, (ii) to sequence the genome of C. cassiicola, (iii) to investigate the cultivar resistance of 10 tobacco cultivars to Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco. The outcome of this study will increase our understanding of this pathogen and help growers to find potential disease resistant cultivar resources for tobacco breeding.

Materials and methods

Strain materials, culture conditions and phylogenetic tree construction

The isolates of C. cassiicola DWZ, WZ-16, WZ-45 with wild-type sensitivity and pathogenicity to tobacco were selected for analysis. It was isolated and identified by the microbiology laboratory of Guizhou Academy of Tobacco Science and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C. Multigene phylogenetic analysis of these isolates were performed using ITS51 and EF1-α52 gene sequences. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method53. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor connection method53 and the optimal tree was drawn to scale. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method. The sequences referenced in this study (Table 1).

The growth and sporulation of C. cassiicola DWZ, WZ-16 and WZ-45 under different temperature and medium were measured. The experiment was conducted by using different agar media, including potato dextrose agar medium (PDA), alkyl ester agar medium (AEA), oatmeal agar medium (OA), maltose yeast extract agar medium (MA), rye agar medium (RA), czapek-Dox agar medium (Czapek), water agar Medium (WA) were cultured in a temperature range of 10 °C to 35 °C. To ensure the reliability of the results, five replicate plates were used for each temperature and medium. AEA medium (5 g/L yeast extract, 6 g/L NaNO3, 1.5 g/L KH2PO4, 0.25 g/L MgSO4, 0.5 g/L KCl, 20 mL/L glycerol, 20 g/L agar) was used for the sporulation culture of fungi. After 5 days of culture, fungal growth was assessed by measuring colony diameter. After 8 days of culture, the spore production and germination were observed by blood cell counting plate. In order to reduce experimental bias, each treatment was repeated three times and the whole experiment was repeated three times to ensure consistency and repeatability of results.

Phenotypic characterization

In accordance with the published literature26,54, the isolate was identified using the PM system (Biolog (https://www.biolog.de/) Hayward, CA, United States) to determine its phenotype. A total of 950 different growth conditions were tested using the PM system, including 190 different carbon sources, 95 different nitrogen sources, 59 different phosphorus sources, 35 different sulfur sources, 94 biosynthetic pathways, 285 nitrogen pathways, and 192 tolerances to different osmotic and pH conditions. All materials, media and reagents for the PM system were purchased from Biolog to ensure experimental consistency. A total of 10 PM plates were used in this study. Plates 1–8 were used to test for catabolic pathways for carbon (PM 1–2), nitrogen (PM 3,6–8), phosphorus (PM 4), and sulfur (PM 4), as well as for biosynthetic pathways while plates 9–10 were used for osmotic/ion (PM 9) and pH effects (PM 10).

Conidia suspension of C. cassiicola was prepared according to the following methods and suspended in an appropriate medium containing sterile FF-IF. After 10 days of incubation, spores produced in the petri dishes were collected using sterile wet cotton swabs. Then, the swabs were rinsed with FF-IF (BIOLOG catalog #72106) inoculum, the conidia suspension was filtered with a double layer of sterile gauze and were finally diluted to the final conidia concentration of 1 × 105 spores/mL55. One hundred microliters of cell dilution suspension with a light transmittance of 62% was added to each well of the PM plate. The fungi were then transferred into a sterile capped tube containing 12 mL of sterile FF-IF. The cell suspension was stirred with the swab to obtain a uniform suspension. The turbidity of the suspension was measured and fungi was continually added to achieve a density of 62% T (transmittance). FF-IF was used for PM plates 1 and 2. FF-IF plus 100 mM D-glucose, 5 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) and 2 mM sodium sulfate was used for plates 3, 5, 6, 7, and 8. FF-IF plus 100 mM D-glucose was used for plate 4. FF-IF plus yeast nitrogen base and 100 mM D-glucose was used for plates 9 and 1032. Plates were incubated in OmniLog at 28 °C for 7 days and readings were taken every 15 min. Phenotypic data were recorded by capturing digital images of microarrays and storing turbidity values. Kinetic and Parametric software (Biolog) was used to analyze the data. The phenotype was estimated according to the area of each well under the staining formation kinetics curve. The experiment was repeated twice.

Whole genome sequencing of C. cassiicola strain of DWZ

Genome sequencing and assembly

DWZ genomic DNA was extracted by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis method, and the collected DNA was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by Qubit®2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Scientific)56.

Illumina NovaSeq PE150 and Pacbio platforms were used for Library construction. The total DNA requirement per sample in Illumina platform was 1 µg, and the Library construction was generated using the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit. The DNA sample was segmented into 350 bp by sonication, then the end of the DNA fragment was polished and connected with the full-length splice, and the PCR products were purified by AMPure using Agilent2100 bioanalyzer and quantified by real-time PCR55. The PacBio Sequel platform builds libraries using single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, inserting 20 kb of templates. Evaluation of library quality on Qubit®2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and Agilent 2100 (Agilent technology) for detection of insert fragment size. The genome was initially assembled using SMRT Link v5.0.1 (https://www.pacb.com/support/software-downloads/) software to filter raw data smaller than 500 bp57,58. The automatic error correction function of SMRT portal software was used to correct errors, and variant Caller module of SMRT Link software was used to correct errors using arrow algorithm.

The sequence data supporting the results of this study has been stored in the NCBI archive with the main entry code PRJNA1056478 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA1056478).

Genome annotation, gene prediction and functional annotation

The process of genome annotation provides important insights into the genetic makeup of an organism, contributing to the understanding of its biology and evolution. Genome component prediction is divided into three main parts, including coding gene, repetitive sequence and non-coding RNA prediction. A complete annotation pipeline (PASA) was developed using the Augustus 2.7 program to retrieve protein-coding genes59. Protein homology detection and intron analysis were performed using GeneWise version 2.4.1 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/~birney/wise2/) software and uniref90 non-redundant protein database. Alignment of known ESTs, full-length cDNAs, and most recently, Trinity RNA-Seq assemblies to the genome. Align the assembly according to the PASA aligned by the overlapped transcript.EVM (EVidenceModeler) and PASA were used to annotate gene structure and update EVM consensus prediction. RepeatMasker v4.0.6 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) software was used to predict interspersed repeat sequences60,61. TRF (tandem repeats finder) v4.07b was used to analyze tandem repeats. TRNAscan-SE (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.download/) software was used to analyze transfer RNA (tRNA) genes62. rRNAmmer v1.2 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/RNAmmer/) software is used to predict ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes63. Small RNA, small nuclear RNA (snRNA), and microRNA (miRNA) were predicted using the Rfam database BLAST64,65.

Multiple nucleotide and protein databases were used to annotate Gene functions to predict their functions, including GO (Gene Ontology)66, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes)67, KOG, NR (Non-Redundant Protein Databases)68, TCDB (Transporter Classification Database)69, P45070, and Swiss-Prot71. A whole genome Blast search (E-value less than 1e-5, minimal alignment length percentage larger than 40%) was performed against above seven databases. Additionally, CAZy (Carbohydrate Active enZYmes) were predicted by carbohydrate Active enZYmes Database72. The secretory proteins were predicted by the SignalP database73. Meanwhile, we analyzed the secondary metabolism gene clusters by the antiSMASH74. We used the PHI (Pathogen Host Interactions)75 and DFVF (database of fungal virulence factors)76 to analyze the pathogenicity and drug resistance of pathogens.

Pathogenicity of Corynespora cassiicola to different level maturity tobacco leaves

Tobacco plants (cv. Yunyan 87) with no disease and insect pests were selected as experimental materials for the pathogenicity test of C. cassiicola. Ten pieces of tobacco leaves at of same maturity, both mature (Lower leaf), proper mature (Middle leaf) and immature (Upper leaf) were used for analyses, respectively. A superficial wound was made on either side of each leaf. Then, a sterile toothpick was used to take a mycelium plug (5 mm) from the edge of 7-day colony on the PDA medium and place it upside down on the wound surface. After inoculation, tobacco leaves were incubated in a climate chamber (28 °C, relative humidity > 80%, under dark conditions). The diameter of the diseased spot on the leaves was measured at 5, 8, and 12 days after inoculation, respectively, and the resistance level of tobacco leaves at different maturities to the Corynespora leaf spot was evaluated according to the diameter of diseased spot.

Tobacco cultivar resistance to Corynespora leaf spot

Tobacco varieties Yunyan 87, Yunyan 85, Yunyan 97, Guiyan 5, Guiyan 8, Honghua Da Jinyuan, Jiucaiping 2, Bina 1, GZ36 and K326 were provided by Tobacco Breeding Engineering Technology Center of Guizhou Academy of Tobacco Science. All tobacco cultivar seeds were seeded in a floating seedling tray (160 well/tray) in a conventional manner, cultured at 15–28 °C under natural light, and managed according to standard seedling procedures. When tobacco seedlings were at the 7–8 leaf stage, 5 weeks after seeding, the first 3–4 leaves (down to up direction) were selected for resistance evaluation. They were cleaned with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, disinfected with 75% alcohol for 30 s, cleaned with sterile water for 4 times, and air dried. Four wounds were punctured on both sides of the veins of each leaf, and the prepared pathogenic plates were inoculated on the wounds and regularly moisturized. After inoculation, the tobacco leaves of each cultivar were incubated at 90% relative humidity with 12 h light/12 h darkness alternation in the artificial climate chamber. Diameters of the disease spot were recorded at 3, 5, 7, and 10 days after inoculation. The experiment was conducted twice with three replications.

Data analysis

SIBM SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM Corp., New York, United States of America) was used to analyze and process the data. The difference was statistically significant when p ≤ 0.0577.

Results

Multigene identification of strain

Three representative strains were selected from isolated C. cassiicola pathogenic fungi, and these strains were identified using ITS and EF-1α primers. Meanwhile, related strains of other hosts were downloaded according to Table 1 for multi-gene combined construction (Fig. 1). The results showed that strains DWZ, WZ-16 and WZ-45 all clustered together with Corynespora cassiicola, and the isolates from tobacco hosts were closely related to the hosts of cucumber, lentil, and blueberry. The isolates were far related to the hosts of green bean, strawberry and kiwi fruit.

Growth of Corynespora cassiicola strain under different temperature and medium conditions

The optimum growth temperature range of DWZ, WZ-16 and WZ-45 strains was 15–30 °C, the fastest growth was at 30 °C, and the growth was limited above 30 °C (Fig. 2A). The optimum temperature range of the three strains for sporulation was 20–30 °C, and the best sporulation temperature was 25 °C (Fig. 2B). The spores produced by the three strains could germinate at 10–35 °C, and the optimal germination temperature was 25 °C (Fig. 2C). These isolates all grew faster on AEA, OA and RA, and slower on Czapek medium than on water medium (Fig. 2D).

Characterization of strain DWZ of C. cassiicola in terms of phenotype

The isolate of C. cassiicola tested in our study presented a typical phenotypic fingerprint. The pathogen could metabolize 89.47% of tested carbon sources, 100% of nitrogen sources, 97.14% of sulfur sources and 100% of phosphorus sources. Almost all phosphorus substrates could be efficiently utilized by pathogens. Meanwhile, the pathogens were efficient in utilizing unusual S-containing compounds. The S-containing compound that was poorly utilized by C. cassiicola was 1-Thio-β-D Glucose. The pathogen presented 94 different biosynthetic pathways (Fig. 3).

Using PM1 and PM2 (carbon source) data, the isolate of C. cassiicola could utilize 177 different carbon sources; about 80 compounds significantly supported the growth of the pathogen (Table 2). In comparison, around 13 compounds significantly inhibited the growth of the pathogen , including Tricarballylic Acid, Glucuronamide, 3-Methylglucose, b-methyl-D-Glucuronic Acid, a-methyl-D-Mannoside, b-methyl-D-Xyloside, D-Tagatose, Capric Acid, Itaconic Acid, Oxalic Acid, Oxalomalic Acid, D-Tartaric Acid, Acetamide, L-Homoserine, L-Methionine, D,L-Carnitine, sec-Butylamine, 2,3-Butanediol, 2,3-Butanone and 3-Hydroxy 2-Butanone (Table 3). Using the PM3 (nitrogen pathways) data, the isolate of C. cassiicola was tested for their ability to grow on 95 different nitrogen sources. The results showed that almost all nitrogen compounds could be efficiently utilized by the pathogen.

Using the PM6 to PM8 (nitrogen pathways) data, the isolate of C. cassiicola showed 285 different nitrogen pathways, indicating that multiple amino acid combinations support the growth of pathogens. Plates PM9 and PM10 were used to test the growth under different osmotic pressures and pH values. C. cassiicola showed active metabolism with up to 10% sodium chloride, up to 6% potassium chloride, up to 5% sodium sulfate, up to 20% ethylene glycol, up to 6% sodium formate, up to 2% urea, up to 12% sodium lactate, up to 200 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), up to 100 mM ammonium sulfate (pH 8.0), up to 100 mM sodium nitrate and up to 80 mM sodium nitrite. When combined with various osmolytes under the 6% sodium chloride treatment, C. cassiicola presented active growth in all tests. Active metabolism was also exhibited in the range of pH values between 3.5 and 10, with optimal pH of around 5.5. When combined with various amino acids at a pH of 4.5, C. cassiicola showed active growth in all tests. In comparison, when combined with various amino acids at a pH of 9.5, the pathogen presented active growth in all tests except for when combined with the amino acids of phenylethylamine. PM 10, wells B1-D12 and E1-G12, tested the decarboxylase and deaminase activities of the pathogen in the presence of amino acids at pH 4.5 and pH 9.5, respectively. C. cassiicola showed both decarboxylase and deaminase activity in the presence of most of the amino acids, except for phenylethylamine.

Whole genome sequencing and statistical analysis

In this study, Illumina PE150 platform with short read length but high quality and Pacbio platform with long read length but low quality were combined to assemble C. cassiicola genome from tobacco host for the first time. A total of 623,983 reads were obtained when the quality criteria were met, of which the N50 read length was 9912 bp and the Mean Read Length was 8265 bp. SMRT Link v5.0.1 software was used to assemble the Genome. The Genome size was 45185409 bp, and 34 contigs were assembled. The contigs N50 length was 2453548 bp. Maximum contig length is 4574915 bp, Gene total length is 20359313 bp, and G + C content is 51.23% (Table 4).

A total of 13,061 protein-coding genes, 2801 interspersed repetitive sequences, 18,246 tandem repeatsand and 202 nocoding RNAs were annotated. The genome assembly of the organism was annotated and 13,061 Protein-coding genes were identified (Table 4). The Gene total length is 20,359,313 bp and the Gene average length is 1559 bp. Protein-coding genes account for almost half of the genome length (45.06%). 2801 interspersed repetitive sequences accounted for 1.223% of the entire genome.

These included 1,174 long terminal repeats (LTR), 892 DNA repeat elements, 634 long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE), 56 short interspersed nuclear elements (SINE), 27 rolling circles (RC) and 18 Unknown sequences (Table 5). 18,246 tandem repeats accounted for 1.7812% of the entire genome. These include 6,735 minisatellite DNAs, 1,442 microsatellite DNAs, and 10,069 TR. The genome was annotated to 202 No-coding RNAs, among which the numbers of tRNA, 5S, 18S, 28S, sRNA and snRNA were 137, 29, 4, 4, 2, 26, respectively (Table 5). In addition, the genome mapping (Fig. 4) provided a visual representation of the whole genome structure of the organism, including the assembled genome sequence, predicted coding genes, and other known data patterns. Overall, the annotation and analysis of genomic assembly provides insights into the genetic makeup of organisms and reveals a variety of genomic features.

Genome Mapping. First circle: the outermost circle is the genome sequence position coordinates; Second circle: genomic GC content: the GC content is counted with a window of 200,000 bp and a step of (200,000) bp. The inward l blue part indicates that the GC content of this region is lower than the average GC content of the whole genome, the outward purple part is the opposite, and the higher the peak indicates a greater difference from the average GC content; Third circle: genomic GC skew value: window (200,000) bp, step (200,000) bp, the specific algorithm is GC/G + C, the inward green part indicates that the content of G in the region is lower than the content of C, the outward pink part is the opposite; The fourth–seventh circle: Gene density (with a window of 200,000 bp and a step length of 200000 bp to count the gene density of coding genes, rRNA, snRNA, tRNA respectively, the darker the color, the greater the density of genes within the window); Innermost circle: donors and acceptors of segmental duplications on fungus chromosomes are connected by purple lines.

Of the 13,061 protein-coding genes identified in the genome of C. cassiicola strain DWZ, the numbers aligned to NR, Swiss-Prot, KOG, TCDB, GO, PHI, DFVF, P450, Secretory Protein, CAZy and Pfam databases were 12,382, 3473, 2128, 541, 8229, 1500, 475, 323, 1202, 694, and 8229. A total of 11,244 gene sequences obtained from strain DWZ were consistent with C. cassiicola, accounting for 90.81% of protein-coding gene sequences in NR database. In addition to C. cassiicola, a high number of homologous genes were also found in Stemphylium lycopersici (130 genes), Alternaria alternata (120 genes), Clohesyomyces aquaticus (100 genes), Periconia macrospinosa (85 genes), Pyrenophora Tritii-Repentis (70 genes), Pyrenochaeta sp. (65 genes), Paraphaeosphaeria sporulosa (60 genes), Stagonospora sp. (41 genes) and Ascochyta rabiei (41 genes) (Table 6).

Among all predicted genes, approximately 63% (8229 genes) were annotated by the GO pathway, and the most annotated genes were binding (4299 genes), metabolic process (4283 genes), catalytic activity (4118 genes), and cellular process (3971 genes) (Fig. 5A). The KEGG pathway is annotated to Cellular Processes (509 genes), Environmental Information Processing (252 genes), Genetic Information Processing (779 genes), Human Diseases (746 genes), Metabolism (2938 genes) and Organismal Systems (565 genes) ([KEGG Copyright Permission] 240,634) (Fig. 5B). The KOG pathway is annotated to General function prediction only (257 genes), Posttranslational modification, protein turnover chaperones (218 genes), Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis (217 genes), Energy production and conversion (197 genes), and Amino acid transport and metabolism (192 genes) (Fig. 5C).

Among the 541 transporters, “electrochemical potential driving transporter” (229 gene) and “major active transporter” (152 gene) were the dominant groups, followed by “channel/pore”(62 gene), “incomplete characterization of transport system” (57 gene), “Accessory Factors Involved in Transport” (32 gene), “Group Translocators” (7 gene) and “Transmembrane Electron Carriers” (2 gene) (Fig. 5D). PHI Phenotype classification divides 1,500 genes into 30 categories, where reduced virulence (542 gene), unaffected pathogenicity (521 gene), loss of pathogenicity (109 gene) and NA (157 gene) are the main groups (Fig. 5E). the CAZy database showed that 694 genes were divided into 6 carbohydrate active gene enzyme families, including carbohydrate binding modules (93 genes), carbohydrate esterases (48 genes), glycoside hydrolases (338 genes), glycosyltransferases (97 genes), polysaccharide lyases (36 genes) and auxiliary activities (138 genes) (Fig. 5F). The results of DFVF showed that 475 fungal virulence factors were annotated. Among them, the Identity with Alternaria brassicicola can reach 99.1%.

Pathogenicity of Corynespora cassiicola to different level maturity tobacco leaves

In our study, Yunyan 87 tobacco leaves with varied maturity were all affected by C. cassiicola at the occurrence stage, and the diameter of leaf spot increased gradually with the increase of leaf maturity with significant differences. Mature leaves were more susceptible than proper mature and immature leaves, and the average diameter of disease spot was 12.95 mm, 10.37 mm, and 8.31 mm at 5 days, 16.38 mm, 11.92 mm, and 8.98 mm at 8 days, and 17.74 mm, 13.40 mm, and 10.48 mm at 12 days (Table 7).

Cultivar resistance to Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco

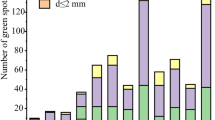

Ten tobacco varieties that were recently grown in a commercial field in the Guizhou province of China were evaluated for cultivar resistance to Corynespora leaf spot. The results showed that all 10 cultivars (lines) varied in their resistance ability to Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco (Fig. 6, Table 8). The highest resistance was found in GZ36 with a spot diameter of 16.25 mm at 7 days; followed by Yunyan 85 with a spot diameter of 24.06 mm at 7 days, K326 with a spot diameter of 28.13 mm at 7 days, Yunyan 97 with a spot diameter of 29.75 mm at 7 days, Honghuadajinyuan with a spot diameter of 31.13 mm at 7 days, Yunyan 87 with a spot diameter of 33.92 mm at 7 days, Guiyan 8 with a spot diameter of 36.75 mm at 7 days, Guiyan 5 with a spot diameter of 40.5 mm at 7 days, Jiucaiping No 2 with a spot diameter of 40.13 mm at 7 days, and the lowest resistance was noted by Bina No 1 with a spot diameter of 44.56 mm at 7 days. However, the diameter of the disease spot of GZ36 increased significantly at 10 days, and 10 varieties were all seriously infected.

Discussion

Corynespora cassiicola is a destructive fungal pathogen distributed throughout the world, existing as a pathogen, saprophyte, and endophyte that has only been observed as an anamorph17. As an important plant pathogenic fungus, the pathogen infects 530 plant species, covering 380 genera, causing irreparable damage18. Extensive genetic and molecular biological studies have been carried out on C. cassiicola78,79, but the metabolic phenotypic diversity and genome-related information of this pathogen from tobacco hosts remains poorly understood. The primary objective of the present investigation is to conduct a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of the growth conditions, metabolic phenotypes and genomics of pathogenic fungi. The results showed that the isolates showed strong metabolic capacity and protein coding ability. Simultaneously, investigations into the varied pathogenicity of C. cassiicola in accordance with different levels of tobacco leaf maturity and cultivar resistance to Corynespora leaf spot were carried out, and the results showed that mature leaves were more susceptible to the disease. No obvious resistant varieties were found among the ten main cultivars in the province of Guizhou, however the germplasm resources need to be further screened.

The Translation Elongation Factor (EF-1α) gene is a central component of eukaryotic translation and plays an important role in the initiation, extension and termination of translation, and has been used as a molecular marker for phylogenetic studies80,81. In this study, multiple genes were used to construct phylogenetic trees. The results showed that the isolates from tobacco host were closely related to cucumber and lentil. The results showed that the optimum growth temperature range of the strain was 15–30 °C and the optimum sporulation temperature range was 20–30 °C. Spores of the strain could germinate at 10–35 °C. Previous studies had reported similar results23,25.

Carbon and nitrogen source were the basic nutrients during microbial growth82. The nutrients released from plants to the surface of their leaves, including various carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids, methanol and various salts, are sufficient to support the growth and development of microorganisms83,84,85. The results showed that C. cassiicola could utilize a wide range of carbon compounds, and almost all nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus sources were also metabolized. Most of the informative utilization patterns for carbon sources included organic acids and carbohydrates, among various amino acids and peptides for nitrogen sources.

Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco often occurs simultaneously with other leaf diseases in the field. The metabolic fingerprint of C. cassiicola in this study was significantly different from that of other tobacco leaf pathogens, such as Alternaria alternata and Pseudomonas syringae. Alternaria alternata, the pathogen resulting in tobacco brown spot, has a relatively small range of available carbon compounds whereby most nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus sources are metabolized28. Pseudomonas syringae, the pathogen resulting in tobacco wildfire, has a relatively small range of available carbon compounds, and most nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus sources cannot be metabolized29. These pathogens may share certain nutrients in tobacco, such as L-arabinose, D-Galactose, D-Trehalose, D-Mannose, D-xylose, D-Mannitol, L-Rhamnose, D-Fructose, A-d-glucose, Maltose, Maltose, B-methyl-D-glucoside, Maltotriose, D-Cellobiose, Dextrin, and Arbutin (all three pathogens can metabolize these efficiently), resulting in their frequent mixing. In future studies, more work is needed to verify this hypothesis.

Additionally, the pathogens had a strong metabolic capacity over various osmotic pressures and pH conditions, which may help C. cassiicola adapt to a variety of environments, enabling it to grow and develop on a variety of hosts. It also exhibited active metabolism in the range of pH values between 3.5 and 10, with an optimal pH of around 5.5. Other related reports indicate that the optimal pH is 686. It has been reported that the pH value of flue-cured tobacco leaves is primarily concentrated between 4.9 and 5.8 in main tobacco producing areas87. This may be due to the tobacco leaves having a more acidic environment, which is more favorable for the growth of eosinophilic pathogens. It has been reported that the optimal pH for A. alternata is 6.0 and for P. Syringae the optimal pH is 5.5, which may be one of the prerequisites for the occurrence of this leaf disease combination28,29.

In our study, C. cassiicola from tobacco hosts showed high decarboxylase activity and high deaminase activity. Deaminase of the pathogen produces acids by catabolism of amino acids, which help to counteract an alkaline pH88. In contrast, a low pH can be counteracted by decarboxylases that generate alkaline amines89. These results suggest that C. cassiicola can adapt to a variety of pH values during the tissue development of a plant. Additionally, acid-loving pathogenic fungi may have strong decarboxylase activity in order to avoid over-acid conditions. This study showed that the growth of C. cassiicola was inhibited in 4% Urea, 20 mM Sodium Benzoate pH 5.2, and pH 9.5 + phenylethylamine which may provide a basis for further research on disease prevention and control. This is consistent with the reported results that a urea-rich medium can inhibit the growth of pathogenic microorganisms86. Related reports showed that A. alternata and P. syringae were also affected by 6% urea, 20 mM sodium benzoate pH 5.2, and pH 9.5 + phenylethylamine which may also provide a basis for further research on prevention and control of diseases28,29. Consequently, the phenotypic characters responsible for the utilization of those sources and the wide range adaptabilities of C. cassiicola could potentially hold a high value in pathogen-tobacco interaction studies and survival of the pathogen in the environment.

The present study involves a genomic analysis of C. cassiicola, a fungal pathogen known to cause economic crop damage, particularly in tobacco. The 45.18 Mb DWZ genome is larger than the average of 36.91 Mb reported for Ascomycota but close to that of the Dothideomycetes (44.59 Mb). In addition, the DWZ genome has 13,061 genes, more than the average 11,000 genes in ascomycetes90. The genome size of C. cassiicola from rubber host is 44.85 Mb, annotated to 17,167 genes, which may be due to the high degree of variation of C. cassiicola between different hosts17. CAZymes play an important role in carbon capture and metabolism91,92, the CAZy database showed that 694 genes were divided into 6 carbohydrate active gene enzyme families, including carbohydrate binding modules (93 genes), carbohydrate esterases (48 genes), glycoside hydrolases (338 genes), glycosyltransferases (97 genes), polysaccharide lyases (36 genes) and auxiliary activities (138 genes). Among pathogens, GHs and CBM are closely related to carbohydrate utilization. A survey conducted by Gai (2019) on the comparative genomics of 82 A. alternata strains found that A. alternata annotated an average of 290–299 GHs and 67–76 CBM genes93. This may be the reason that C. cassiicola carbon source has better metabolic capacity than A. alternata.

This study showed that tobacco leaves with different levels of maturity showed varied resistance to C. cassiicola, the resistance of ten tobacco varieties were different, and all were infected after 10 days. The difference of leaf susceptibility in different leaf positions may be due to the difference in the content of sugar, nicotine, starch and other chemical components in tobacco leaves under different levels of maturity. The content of free amino acids, nicotine, soluble sugars and reducing sugars in leaf leachate in mature leaves is higher than that in immature leaves94. These substances comprise important nutrients and may be beneficial to the growth and development of pathogenic microorganisms, thus the lower, older leaves are more seriously damaged. It was reported that there were significant differences in invertase activity, nitrate reductase activity, pigment content, total sugar content, total nitrogen content, and sugar-nitrogen ratio in leaves of different genotypes of flue-cured tobacco95.

The establishment of accurate, efficient, and rapid disease evaluation methods for tobacco varieties is an important basis for screening resistant varieties. There are many resistance methods for tobacco varieties. The twelve well plate method and petri dish seedling method cannot reflect the actual resistance of flue-cured tobacco, and the injection inoculation method has higher requirements for experimental operation96. The tobacco resistance level was identified by artificial identification of seedling inoculation. This method is simple to operate and low cost and can be used to quickly and in large quantities to screen the resistance of different varieties of cassava. However, inoculating in vitro leaves at the seedling stage has certain limitations and cannot simulate the complex and changing environment in the field. This study provided a basis for the resistance evaluation of tobacco varieties to Corynespora leaf spot, which needs further evaluation. At the same time, the resistance of C. cassiicola to different leaf positions at different maturity levels was investigated to provide seed resources for the breeding of resistant tobacco varieties.

This study also provided a basis for the development of management regimes for C. cassiicola. In our study, C. cassiicola could not grow with 4% urea, 20 mM sodium benzoate (pH 5.2), 100 mM Sodium Nitrite or pH 9.5 + phenylethylamine. Thus, changing the pH or osmolyte environment in tobacco leaves to make it unadaptable for the pathogen C. cassiicola may also reduce the damage caused by Corynespora leaf spot. However, the environmental conditions required to inhibit the growth of C. cassiicola might be challenging to achieve. Further studies should be conducted to verify this hypothesis in a future study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the growth conditions, metabolic phenotypic characteristics, genome and pathogenicity of C. cassiicola were evaluated in this study, which increased the understanding of this pathogen. Specifically, we determined the optimal culture conditions for C. cassiicola isolate, in which the optimal temperature for growth and sporulation was 25–30 °C, and the optimal medium was AEA medium. In addition, we also analyzed the metabolic Phenotype of C. cassiicola by using Biolog Phenotype MicroArray, and the results showed that C. cassiicola showed high metabolic levels for carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur sources. In addition, the DWZ genome was sequenced using Illumina HiSeq and Pacbio bioscience technology and assembled into 45.9 Mbp, with a total of 13,061 genes predicted and analyzed using various databases. Finally, the resistance evaluation of leaves with different maturity and ten varieties was carried out. The results showed that mature leaves were more susceptible to infection and no obvious disease resistance was found in the ten varieties. This study provided a theoretical basis for the comprehensive control and breeding of tobacco Corynespora leaf spot.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study can be found in onlinerepositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accessionnumber(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material. The sequence data supporting the results of this study has been stored in the NCBI archive with the main entry code PRJNA1056478 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA1056478).

References

Wang, H. C. et al. Activities of azoxystrobin and difenoconazole against Alternaria alternata and theircontrol efficacy. Crop Prot. 90, 54–58 (2016).

Chen, Q. L. et al. Fungal composition and diversity of the tobacco leaf phyllosphere during curing of leaves. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.554051 (2020).

Déon, M. et al. Characterization of a cassiicolin-encoding gene from Corynespora cassiicola, pathogen of rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Plant Sci. 185, 227–237 (2012).

MacKenzie, K. J., Sumabat, L. G., Xavier, K. V. & Vallad, G. E. A review of Corynespora cassiicola and its increasing relevance to tomato in Florida. Plant Health Progress. 19(4), 303–309 (2018).

Miyamoto, T., Ishii, H., Seko, T., Kobori, S. & Tomita, Y. Occurrence of Corynespora cassiicola isolates resistant to boscalid on cucumber in Ibaraki prefecture, Japan. Plant Pathol. 58(6), 1144–1151 (2009).

Conner, K. N., Hagan, A. K. & Zhang, L. First report of Corynespora cassiicola-incited target spot on cotton in Alabama. Plant Dis. 97(10), 1379–1379 (2013).

Fajola, A. O. & Alasoadura, S. O. Corynespora leaf spot, a new disease of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Plant Dis. 57, 375–378 (1973).

Koenning, S. R., Creswell, T. C., Dunphy, E. J., Sikora, E. J. & Mueller, J. D. Increased occurrence of target spot of soybean caused by Corynespora cassiicola in the southeastern United States. Plant Dis. 90, 974 (2006).

Carris, L. M., Glawe, D. A. & Gray, L. E. Isolation of the soybean pathogens Corynespora cassiicola and Phialophora gregata from cysts of Heterodera glycines in Illinois. Mycologia 78(3), 503–506 (1986).

Zhao, D. L., Shao, C. L., Gan, L. S., Wang, M. & Wang, C. Y. Chromone derivatives from a sponge-derived strain of the fungus Corynespora cassiicola. J. Nat. Prod. 78(2), 286–293 (2015).

Huang, H. K. et al. Subcutaneous infection caused by Corynespora cassiicola, a plant pathogen. J. Infect. 60(2), 188–190 (2010).

Zhu, H. G., Wang, J. J., Hu, R. H., Liu, Q. G. & Luo, J. J. Identification of pathogen causing Corynespora leaf spot of tobacco in Jiangxi. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 42, 62–66 (2015).

Collado, J., Platas, G., Gonzalez, I. & Pelaez, F. Geographical and seasonal influences on the distribution of fungal endophytes in Quercus ilex. New Phytol. 144, 525–532 (1999).

Déon, M. et al. First characterization of endophytic Corynespora cassiicola isolates with variant cassiicolin genes recovered from rubber trees in Brazil. Fungal Divers. 54(1), 87–99 (2012).

Lee, S., Melnik, V., Taylor, J. & Crous, P. Diversity of saprobic hyphomycetes on Proteaceae and Restionaceae from South Africa. Fungal Divers. 17, 91–114 (2004).

Cai, L., Ji, K. F. & Hyde, K. D. Variation between freshwater and terrestrial fungal communities on decaying bamboo culms. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 89(2), 293–301 (2006).

Lopez, D. et al. Genome-wide analysis of Corynespora cassiicola leaf fall disease putative effectors. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00276 (2018).

Dixon, L. J., Schlub, R. L., Pernezny, K. & Datnoff, L. E. Host specialization and phylogenetic diversity of Corynespora cassiicola. Phytopathology 99(9), 1015–1027 (2009).

Déon, M. et al. Diversity of the cassiicolin gene in Corynespora cassiicola and relation with the pathogenicity in Hevea brasiliensis. Fungal Biol. 118(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2013.10.011 (2014).

Breton, F., Sanier, C. & D’Auzac, J. Role of cassiicolin, a host-selective toxin, in pathogenicity of Corynespora cassiicola, causal agent of a leaf fall disease of Hevea. J. Rubber Res 3(2), 115–128 (2000).

Romruensukharom, P., Tragoonrung, S., Vanavichit, A. & Toojinda, T. Genetic variability of Corynespora cassiicola populations in Thailand. J. Rubber Res. 8(1), 38–49 (2005).

Qi, Y. et al. Molecular and pathogenic variation identified among isolates of corynespora cassiicola. Mol. Biotechnol. 41(2), 145–151 (2009).

Zhang, H. et al. Biological characteristics of the pathogen of defoliation of Corynespora brasiliensis. J. Trop. Crops 28, 83–87 (2007).

Tian, X. L., Liu, M. T. & Xu, R. F. Study on the factors of conidial germination of Corynespora cassiicola. J. Jilin Agric. Sci. 31, 39–41 (2006).

Xu, R. F., Wu, L. M. & Lu, N. H. Study on pathogen identification and biological characteristics of tomato brown spot. J. Henan Agric. Univ. 39, 312–316 (2005).

Bochner, B. R., Gadzinski, P. & Panomitros, E. Phenotype microarrays for high-throughput phenotypic testing and assay of gene function. Genome Res. 11(7), 1246–1255 (2001).

Bochner, B. R. New technologies to assess genotype-phenotype relationships. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4(4), 309–314 (2003).

Wang, H. C. et al. Phenotypic analysis of Alternaria alternata, the causal agent of tobacco brown spot. Plant Pathol. J. 14(2), 79–85 (2015).

Guo, Y. S., Su, X. K., Cai, L. T. & Wang, H. C. Phenotypic characterization of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci, the causal agent of tobacco wildfire. J. Plant Pathol. 99, 499–504 (2017).

Wang, H. C. et al. Metabolic phenotype characterization of Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of gray mold. Front. Microbiol. 9, 470 (2018).

Wang, H. C. et al. Phenotypic fingerprints of Ralstonia solanacearum biovar 3 strains from tobacco and tomato in China assessed by Phenotype MicroArray analysis. Plant Pathol. J. 14, 38–43 (2015).

Wang, M. S. et al. Phenotypic analysis of Phytophthora parasitica by using high throughput phenotypic microarray. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 55(10), 1356–1363 (2015).

Youssef, N. H. et al. The genome of the anaerobic fungus Orpinomyces sp. strain C1A reveals the unique evolutionary history of a remarkable plant biomass degrader. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4620–4634 (2013).

Faino, L. et al. Single-molecule real-time sequencing combined with optical mapping yields completely finished fungal genome. mBio 6, e00936-15 (2015).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Completing bacterial genome assemblies with multiplex minion sequencing. Microb. Genom. 3, e000132 (2017).

Ludden, C. et al. Sharing of carbapenemase-encoding plasmids between Enterobacteriaceae in UK sewage uncovered by MinION sequencing. Microb. Genom. 3, 1–12 (2017).

Liem, M. et al. De novo whole-genome assembly of a wild type yeast isolate using nanopore sequencing. F100Research 6, 618 (2017).

Chin, C. S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10, 563–569 (2013).

Brown, S. D. et al. Comparison of single-molecule sequencing and hybrid approaches for finishing the genome of Clostridium autoethanogenum and analysis of CRISPR systems in industrial relevant Clostridia. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 40 (2014).

Schmid, M. et al. Pushing the limits of de novo genome assembly for complex prokaryotic genomes harboring very long, near identical repeats. Nucl. Acids Res. 46(17), 8953–8965 (2018).

Ailloud, F. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Ralstonia solanacearum reveals candidate genes for host specificity. Bmc Genom. 16(1), 270 (2015).

Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC). 2014. Pathogen risk list.Online publication. http://www.frac.info/docs/default-source/publications/pathogen-risk/pathogen-risk-list.pdf?sfvrsn=8.

Miyamoto, T. et al. Distribution and molecular characterization of Corynespora cassiicola isolates resistant to boscalid. Plant Pathol. 59, 873–881 (2010).

Vawdrey, L. L., Grice, K. R. E. & Westerhuis, D. Field and laboratory evaluations of fungicides for the control of brown spot (Corynespora cassiicola) and black spot (Asperisporium caricae) of papaya in far north Queensland, Australia. Austral. Plant Pathol. 37, 552–558 (2008).

Adkison, H., Margenthaler, E., Burlacu, V., Willis, R. & Vallad, G. Occurrence of resistance to respiratory inhibitors in Corynespora cassiicola isolates from Florida tomatoes. Phytopathology 102(S4), 2 (2012).

Li, B. X., Liu, X. B., Lin, C. H., Shi, T. & Huang, G. X. Resistance evaluation of main Hevea brasiliensis germplasms to Corynespora leaf fall disease in China. Plant Prot. 40, 86–92 (2014).

Lu, X., Peng, J. H., Zhang, K. L. & Huang, G. X. Resistance identification of the main Hevea brasiliensis germplasm to Corynespora leaf fall disease. J. Trop. Crops 28, 73–77 (2008).

Wang, H. Z., Li, S. J. & Guan, W. Identification of resistance to cucumber brown spot and its cultivars. China Veg. 176, 26–27 (2008).

Gao, W., Wang, Y. & Zhang, C. X. Resistance identification of different cucumber varieties to Corynespora leaf spot. North. Hortic. 11, 110–112 (2016).

Lu, N. H. & Wu, L. M. Effect of Corynespora cassiicola toxin on resistant and susceptible cucumber varieties. J. Microbiol. 04, 101–103 (2007).

Xie, S. F. et al. First report of leaf spot caused by Corynespora cassiicola on Acanthus ilicifolius in China. Plant Dis. 105(2), 509–509 (2021).

Shimomoto, Y. et al. Pathogenic and genetic variation among isolates of Corynespora cassiicola in Japan. Plant Pathol. 60(2), 253–260 (2011).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Von Eiff, C. et al. Phenotype microarray profiling of staphylococcus aureus mend and hemb mutants with the small-colony-variant phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 188, 687–693 (2006).

Li, Z. et al. Characteristics of Epicoccum latusicollum as revealed by genomic and metabolic phenomic analysis, the causal agent of tobacco Epicoccus leaf spot. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1199956 (2023).

Lim, H. J., Lee, E. H., Yoon, Y., Chua, B. & Son, A. Portable lysis apparatus for rapid single-step DNA extraction of Bacillus subtilis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120(2), 379–387 (2016).

Ardui, S., Ameur, A., Vermeesch, J. R. & Hestand, M. S. Single molecule real-time (smrt) sequencing comes of age: Applications and utilities for medical diagnostics. Nucleic Acids Res.. 46(5), 2159–2168 (2018).

Reiner, J. et al. Cytogenomic identification and long-read single molecule real-time (smrt) sequencing of a bardet-biedl syndrome 9 (bbs9) deletion. Npj Genom. Med. 3, 3 (2018).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cdna alignments to improvede novo gene finding. Bioinformatics. 24(5), 637–644 (2008).

Sui, Y. et al. A comparative analysis of the microbiome of kiwifruit at harvest under open-field and rain-shelter cultivation systems. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.757719 (2021).

Saha, S., Bridges, S., Magbanua, Z. V. & Peterson, D. G. Empirical comparison of ab initio repeat finding programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 36(7), 2284–2294 (2008).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. Trnascan-se: A program for improved detection of transfer rna genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25(5), 955–964 (1997).

Lagesen, K. et al. Rnammer: Consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal rna genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35(9), 3100–3108 (2007).

Gardner, P. P. et al. Rfam: Updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(Database), 136–140 (2009).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 13.0: Shifting to a genome-centric resource for non-coding rna families. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 335–342 (2018).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25(1), 25–29 (2018).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000).

Henikoff, S., Henikoff, J. G. & Pietrokovski, S. Blocks+: A non-redundant database of protein alignment blocks derived from multiple compilations. Bioinformatics 15(6), 471–479 (1999).

Saier, M. H. et al. The transporter classification database (tcdb): Recent advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(1), 372–379 (2016).

Denisov, I. G., Makris, T. M., Sligar, S. G. & Schlichting, I. Structure and chemistry of cytochrome p450. Chem. Rev. 105(6), 2253–2278 (2005).

Boeckmann, B. The swiss-prot protein knowledgebase and its supplement trembl in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31(1), 365–370 (2003).

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (cazy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(1), 490–495 (2013).

Choo, K. H., Tan, T. W. & Ranganathan, S. SPdb-a signal peptide database. BMC bioinf. 6(1), 1–8 (2005).

Medema, M. H. et al. Antismash: Rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(suppl 2), 339–346 (2011).

Winnenburg, R. Phi-base: A new database for pathogen host interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 34(90001), 459–464 (2006).

Lu, T., Yao, B. & Zhang, C. Dfvf: Database of fungal virulence factors. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2012, s32 (2012).

Mao, H., Wang, K., Wang, Z., Peng, J. & Ren, N. Metabolic function, trophic mode, organics degradation ability and influence factor of bacterial and fungal communities in chicken manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 302, 122883 (2020).

Nghia, N. A. et al. Morphological and inter simple sequence repeat (issr) markers analyses of corynespora cassiicola isolates from rubber plantations in malaysia. Mycopathologia 166(4), 189–201 (2008).

Hieu, N. D., Nghia, N. A., Chi, V. T. Q. & Dung, P. Genetic diversity and pathogenicity of Corynespora cassiicola isolates from rubber trees and other hosts in Vietnam. J. Rubber Res. 17, 187–203 (2014).

Silva, W. P., Karunanayake, E. H., Wijesundera, R. L. & Priyanka, U. M. Genetic variation in corynespora cassiicola: A possible relationship between host origin and virulence. Mycol. Res. 107(5), 567–571 (2003).

Zhao, P. et al. Dna barcoding mushroom spawn using ef-1α barcodes: A case study in oyster mushrooms (pleurotus). Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.624347 (2021).

Khalil, S. & Alsanius, B. W. Utilisation of carbon sources by Pythium, Phytophthora and Fusarium species as determined by Biolog® microplate assay. Open Microbiol. J. 3, 9–14 (2009).

Mercier, J. & Lindow, S. E. Role of leaf surface sugars in colonization of plants by bacterial epiphytes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66(1), 369–374 (2000).

Fiala, V., Glad, C., Martin, M., Jolivet, E. & Derridj, S. Occurrence of soluble carbohydrates on the phylloplane of maize (Zea mays L.): Variations in relation to leaf heterogeneity and position on the plant. New Phytol. 115(4), 609–615 (1990).

Fougere, F., Le Rudulier, D. & Streeter, J. G. Effects of salt stress on amino acid, organic acid, and carbohydrate composition of roots, bacteroids, and cytosol of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plant Physiol. 96(4), 1228–1236 (1991).

Pan, Z. M. et al. Molecular identification and biological characteristics of Corynespora flue cured Tobacco leaf spot pathogen based on ITS. J. Mol. Plant Breed. 12, 7138–7145 (2021).

Zhou, H., Xu, Z. C., Bi, Q. W. & Wang, J. Distribution of pH value in flue—Cured tobacco leaves of in China and the correlation analysis of their chemical components. J. Jiangxi Agric. Univ. 31, 461–466 (2009).

Durso, L. M., Smith, D. & Hutikins, R. W. Measurements of fitness and competition in commensal Escherichia coli and E. coli O157:H7 strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 6466–6472 (2004).

Maurer, L. M., Yohannes, E., Bondurant, S. S., Radmacher, M. & Slonczewski, J. L. pH regulates genes for Flagellar Motility, catabolism, and oxidative stress in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 187, 304–319 (2005).

Mohanta, T. K. & Bae, H. The diversity of fungal genome. Biol. Proc. Online https://doi.org/10.1186/s12575-015-0020-z (2015).

Park, B. H., Karpinets, T. V., Syed, M. H., Leuze, M. R. & Uberbacher, E. C. Cazymes analysis toolkit (cat): Web service for searching and analyzing carbohydrate-active enzymes in a newly sequenced organism using cazy database. Glycobiology 20(12), 1574–1584 (2010).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (cazy): An expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(Database), D233–D238 (2009).

Gai, Y. P. Two Tales of Alternaria Alternata: Comparative Genomics and Function of bZIP Transcription Factor (Zhejiang University, 2019).

Zhang, M. H., Zhang, J. R., Jia, W. X., Zhao, Y. & Ma, R. The relationship between maturity or senescence of tobacco leaves and brown spot. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 28, 49–54 (1998).

Zhang, S. J., Huang, Y. J., Ren, Q. C. & Yang, T. Z. Differences in foliar carbon and nitrogen metabolism among genotypes of flue-cured tobacco. Acta Agric. Boreali-sin. 25, 217–220 (2010).

Lu, N. et al. ldentifying resistance of tobacco varieties against bacterial Wilt. Hubei Agric. Sci. 54, 864–867 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of the following people for providing laboratory assistance at the Guizhou Academy of Tobacco Science as part of this project: Ting-Ting Liu, and Jun Jiang. We also thank the reviewers for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Guizhou Science Technology Foundation (Qiankehe Talent Platform-CXTD[2023]021, ZK[2021]Key036), China National Tobacco Corporation (110202101048(LS-08),110202001035(LS-04)), Zunyi Branch of Guizhou Tobacco Company (2022XM09), ‘Hundred’ Level Innovative Talent Foundation of Guizhou Province (GCC[2022]028-1), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160522, 31960550), Guizhou Province Applied Technology Research and Development Funding Post-subsidy Project, and Guizhou Tobacco Company (2024XM06, 2020XM22, 2020XM03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: H.-C.W., J.-R.H., C.-H.S. and R.-C.F. Performed the experiments: M.-L.S., X.-H.Z., T.-L., J.-Y.G., and C.-Y.H. Wrote and revised the paper: H.-C.W., R.-C.F., and S.-B.Z. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, R., Wang, H., Zhang, X. et al. Characteristics of Corynespora cassiicola, the causal agent of tobacco Corynespora leaf spot, revealed by genomic and metabolic phenomic analysis. Sci Rep 14, 18326 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67510-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67510-y