Abstract

Dual-task performance holds significant relevance in real-world scenarios. Implicit learning is a possible approach for improving dual-task performance. Analogy learning, utilizing a single metaphor to convey essential information about motor skills, has emerged as a practical method for fostering implicit learning. However, evidence supporting the effect of implicit learning on gait-cognitive dual-task performance is insufficient. This exploratory study aimed to examine the effects of implicit and explicit learning on dual-task performance in both gait and cognitive tasks. Tandem gait was employed on a treadmill to assess motor function, whereas serial seven subtraction tasks were used to gauge cognitive performance. Thirty healthy community-dwelling older individuals were randomly assigned to implicit or explicit learning groups. Each group learned the tandem gait task according to their individual learning styles. The implicit learning group showed a significant improvement in gait performance under the dual-task condition compared with the explicit learning group. Furthermore, the implicit learning group exhibited improved dual-task interference for both tasks. Our findings suggest that implicit learning may offer greater advantages than explicit learning in acquiring autonomous motor skills. Future research is needed to uncover the mechanisms underlying implicit learning and to harness its potential for gait-cognitive dual-task performance in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Performing two different tasks simultaneously, known as a dual-task condition, can impair performance in either or both tasks. This phenomenon is referred to as “dual-task interference” or “dual-task interaction”1,2. Although several theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon1,3 the “Capacity-sharing theory” has been the most dominant for the last few decades. According to this theory, cognitive resources for processing information are limited and are divided into two tasks performed simultaneously, resulting in slower information processing and reduced performance under dual-task conditions4,5. In real-life situations, the capacity to safely perform certain tasks (such as thinking about daily activities) while walking is essential for enhancing social engagement and preventing accidental falls. Previous studies using the dual-task paradigm have demonstrated that individuals who exhibit a greater degree of dual-task interference in gait performance have a higher risk of falling6,7,8. Therefore, an approach to improve dual-task interference is necessary for gait training and rehabilitation.

Dual-task training has been proposed as a rehabilitation approach to improve dual-task performance9. It involves the simultaneous performance of a primary gait task (such as normal gait, precision step) and a secondary task, such as a cognitive task (such as serial subtraction, visual memory task) or a motor task (such as carrying a glass of water with a tray)10,11,12. Previous studies have shown that it can decrease dual-task interference in gait performance among different populations11,13,14,15. However, limited studies have investigated the effects of dual-task interference on cognitive performance. Because performance under dual-task conditions depends on how individuals prioritize their efforts on each task, or “task prioritization”16, studies utilizing dual-task training should also measure secondary cognitive task performance to ensure that dual-task performance is truly improved17.

Implicit learning is another potential strategy for improving dual-task performance18. Motor learning theory encompasses the multidisciplinary knowledge regarding how individuals learn and acquire novel motor skills, playing a vital role in rehabilitation approaches, especially for neurological populations19,20. Motor learning mechanisms can be classified into two main types: explicit and implicit learning21. Explicit learning involves individuals acquiring a novel motor skill along with an increase in verbal knowledge related to the skill, termed “knowledge of performance,” and the utilization of cognitive resources21. Conversely, implicit learning refers to a form of learning characterized by little or no increase in verbal knowledge and occurs without awareness21. It is considered applicable to individuals with impaired cognitive function18,22,23 as it involves fewer cognitive resources24. Additionally, the execution of motor skills acquired through implicit learning requires fewer cognitive resources, resulting in sparing resources for secondary tasks25,26. Analogy learning, where a single metaphor is utilized as instruction to provide essential information about motor skills, has been proposed as a practical approach to induce implicit learning18,27. For example, to facilitate step length, direct verbal advice was provided in an explicit learning manner. Conversely, the analogy “Walk as if you follow the footprints in the sand” was provided to the participants in an implicit learning manner28. Previous studies in sports science25,26,29,30 and rehabilitation medicine31,32,33 have investigated the impact of implicit learning utilizing analogy, and some of them revealed that implicit learning leads to improved and more stable motor performance under dual-task conditions18,25,26. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have only been a few studies investigating the differences between implicit and explicit learning in gait-cognitive dual-task conditions, and measuring secondary cognitive performance, even though the mentioned aspects are of great importance in daily life activities17.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the differences in the effects of implicit and explicit learning under the gait-cognitive dual-task condition on dual-task interference for both gait and cognitive tasks. This study applied tandem gait as the motor task and local dynamic stability (LDS) as its parameter. There is no precedent for a study that has employed both, making it an exploratory endeavor.

Results

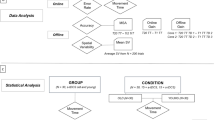

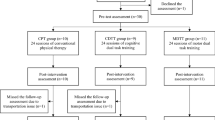

Participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. In the present study, three participants in the implicit learning (IL) group and two in the explicit learning (EL) group were allowed to move their arms with no restriction to adjust the gait-task difficulty, and none of the participants required any physical support for safety. Supplementary Table S1 shows the results of the two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc analysis of gait and cognitive parameters. The results of the statistical analyses of dual-task cost (DTC) are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Figure 1 displays scatter graphs of the individual data. As shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1, the two-way mixed ANOVA of local dynamic stability (LDS) in the dual-task (DT) condition revealed significant effects for the within-subjects factor (Pre-training vs. Post-training) (F(1, 28) = 4.95, P = 0.034, partial η2 = 0.15) and the interaction effect (F(1, 28) = 5.28, P = 0.029, partial η2 = 0.16). Post-hoc analysis showed a significant improvement in the IL group (P = 0.0068, Bonferroni corrected). With regard to the difference in training effects between the two groups, this result indicated that the improvement in LDS under DT conditions was greater in the IL group than in the EL group. The results of standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation of mediolateral (ML) distance, cognitive task performance (number of correct answers), DTC of LDS (DTCLDS) and DTC of the cognitive task performance (DTCCog) in DT condition respectively, showed that the within-subjects factor was significant; however, neither their between-subjects factor nor the interaction effect was significant. Multiple comparisons, such as post-hoc analysis of SD and coefficient of variation of ML distance, cognitive task performance, DTCLDS and DTCCog in DT condition, revealed significant differences in the IL group. In accordance with a previous study17, Fig. 2 displays a scatter plot of changes through tandem gait training in the DTC of both the LDS and cognitive task performance to characterize the change pattern of gait-cognitive dual-task interference. ΔDTC represents the difference between DTC at post- and pre-training (\(\Delta DTC = DTC at Post- DTC at Pre\)), and a positive ΔDTC indicates improvement in dual-task interference through the training17. The number of “knowledge of performance” reported by the participants in the IL and EL groups were 0.9 ± 0.6 and 2.1 ± 1.1, respectively (mean ± SD). Welch’s t-test on the number of “knowledge of performance” revealed a significant difference (t = − 3.83, df = 22, P = 0.00092, Effect size d = 1.40).

The results of gait and cognitive parameters are displayed in the scatter graphs, showing individual data points measured at pre- and post-training. Each color represents its respective group and condition: implicit learning group under single-task condition (IL-ST), implicit learning group under dual-task condition (IL-DT), explicit learning group under single-task condition (EL-ST), and explicit learning group under dual-task condition (EL-DT). Long black bars and error bars represent the means and standard errors of the parameter, respectively. DTCLDS, DTCCog, and the number of correct answers display data under DT conditions. * indicates significant differences between post- and pre-training (post-hoc analysis [Post—Pre], P < 0.05 [Bonferroni corrected]). † indicates the significance of the interaction effect derived from the result of two-way mixed ANOVA (F(1, 28) = 5.28, P = 0.029, partial η2 = 0.16). IL, implicit learning; EL, explicit learning; ST, single-task; DT, dual-task; SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; LDS, local dynamic stability; DTC, dual-task cost; DTCLDS, DTA of LDS; DTCCog, DTC of the cognitive task.

Individual data points and means of changes in DTCs of both LDS and cognitive task performance (number of correct answers) through the gait training. ΔDTC represents the difference between DTC at post- and pre-training. The error bars indicate the 95% CI of the DTCs. This figure is from the framework presented in the previous study17.

Discussion

Although this was an exploratory study, it demonstrated that IL could enhance both gait and cognitive performance under DT conditions. Regarding the disparity in training effects, the IL group exhibited greater improvement in LDS than the EL group under DT conditions. However, no significant difference was observed in the improvement of cognitive task performance between the IL and EL groups. Given that the number of “knowledge of performance” in the EL group exceed that in the IL group, the EL group was presumed to have explicitly acquired the gait task, whereas the IL group engaged in implicit learning. This suggests distinct learning processes between the IL and EL groups21.

Consistent with a previous study that conducted tandem gait training34, improvements in the SD and coefficient of variation of ML distance were observed in the IL group under DT conditions. Additionally, this study showed an improvement in the LDS in the IL group under DT conditions. The SD and coefficient of variation of the ML distance and LDS are parameters employed to measure dynamic stability and disturbance in gait-related nonlinear data series. Therefore, these results suggest that the IL group learned how to maintain balance under gait-cognitive DT conditions. In the comparison between the IL and EL groups, the IL group demonstrated greater improvement in LDS under DT conditions. This result further indicates that IL may offer advantages in learning to perform a gait task under gait-cognitive DT conditions compared with EL. This interpretation is supported by previous findings18,25,26,32,35, which suggest that motor performance acquired through IL tends to be more stable than that acquired through EL under motor-cognitive DT conditions.

As displayed in Figs. 1 and 2, the dual-task interference of the cognitive task, referred to as DTCCog, improved through training in the IL group. Previous studies have revealed that cognitive resources must be allocated to maintain postural balance during challenging gait tasks1,36. In this study, participants were instructed to prioritize the cognitive task as much as possible under DT conditions. Essentially, they needed to allocate available cognitive resources to the cognitive task, while reserving those needed for the gait task. The “capacity sharing theory”4,5 hypothesizes that it becomes easier to perform a secondary cognitive task during a primary motor task when fewer cognitive resources are required for the motor task. Therefore, our results suggest that the IL group was able to reduce the cognitive resources needed for the gait task through training, resulting in more cognitive resources to be allocated to the cognitive task. Interestingly, our results showed that LDS improved more in the IL group than in the EL group under the DT condition (Fig. 1), and that the change pattern of dual-task interference in the IL group exhibited a “mutual facilitation” pattern, indicating an improvement in both dual-task interferences of gait and cognitive tasks (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that IL can enhance autonomous motor performance independently of voluntary control and attention compared with EL. This not only leads to a reduction in the cognitive resources required for the gait task but also improves performance with less cognitive effort. As mentioned in a previous study18, mechanisms underlying IL have been proposed to involve motor skills learned with few or no explicit rules, resulting in offloading to working memory or cognitive resources.

According to the stages of the learning model, our findings suggest that IL can facilitate the acquisition of procedural knowledge independent of declarative knowledge, making it a suitable modality for associative and autonomous stages, as previously mentioned18,22,23,37,38. IL holds promise as a viable learning method in the field of gait training and rehabilitation, particularly for improving dual-task performance. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of IL and develop a rehabilitation approach leveraging IL for enhancing gait-cognitive dual-task performance in clinical populations.

Our study has a few limitations. First, gait performance in the ST condition showed no significant improvement after training. This could be attributed to a potential ceiling effect or an insufficient number of training sessions. Nevertheless, the observed improvement in parameters under the DT condition suggested some degree of learning effect on tandem gait. Our findings regarding the improvement of postural perturbation (SD and coefficient of variation of ML distance) align with those of previous research34. Second, as out study applied the LDS technique to assess tandem gait performance, further exploration of this application is warranted. However, previous studies have successfully employed LDS or Lyapunov exponent (LyE) techniques to assess walking39,40,41, running42,43 and walking with perturbations41, suggesting the suitability of LDS for tandem gait measurement. Third, the measurement duration was limited to 30 s due to device constraints. Given that LDS or LyE can be influenced by data series length40, our results may be impacted by this constraint. Fourth, the absence of a power analysis in this study raises the possibility of insufficient statistical power. Fifth, task difficulty may have varied among participants.

Conclusion

This randomized study aimed to compare the impact of IL and EL on gait and cognitive performance using a gait-cognitive dual-task paradigm. The IL group demonstrated a significant improvement in gait performance under dual-task conditions compared with the EL group. Additionally, our findings indicated that the IL group exhibited improved dual-task interference for both gait and cognitive tasks under dual-task conditions. These results suggest that IL may offer greater advantages in acquiring autonomous motor skills with reduced attentional demand compared with EL. However, given the exploratory nature of this study, further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism of IL and establish a practical approach utilizing IL in clinical populations.

Methods

Participants

Thirty healthy community-dwelling older individuals participated in the study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) ages ranging from 60 to 80 years, (2) being capable of tandem gait for 10 m on the ground, and (3) being capable of standing on each leg for 15 s. The exclusion criteria were (1) any past orthopedic or neuromuscular disease, (2) being suspected to have cognitive impairment (MMSE < 26), and (3) having severe pain with normal gait movement. The participants were randomized by matching age and sex into two groups: implicit learning (IL) and explicit learning (EL). Grip strength with the dominant hand of each participant was recorded as an index of physical function45. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethical board of the University of Tokyo (2022324NI). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Task settings and performance measurements

A gait-cognitive dual-task paradigm was used in this study. The details of the tasks and performance measurements are as follows:

Motor task: tandem gait on a treadmill

Tandem gait is a type of gait task that involves walking in a straight line, placing one foot directly in front of the other, with the heel touching the toes, and has been used to detect gait balance disabilities44. A previous study reported the improvement of tandem gait balance through training34. Therefore, we applied it as the motor learning task in this study, requiring participants to learn it with no prior experience.

The participants performed a tandem gait on a treadmill (BW-SRM16, ALL MARKET JAPAN, Gunma, Japan) with their bare feet in order to avoid influences from different shoe types. The velocity of the treadmill was set at 1.0 km/h, and the handrail was placed on the right side for safety. The center line was indicated by a white tape, and the participants were instructed to place their feet on the extension of the line (Fig. 3a). The participants were also instructed to hold their arms crossed in front of their chests. At the beginning of the study, all the participants performed the tandem gait task for a minimum time (approximately 30 s) to ensure safety. If participants could not safely perform the tandem gait on the treadmill with their arms crossed, they were allowed to move their arms without restriction to adjust the task difficulty.

Tandem gait task conditions. (a) A white tape on the treadmill indicated the center line. The participants were instructed to put their feet on the extension of the line in the gait task. (b) The markers of the motion capture system were attached to the bilateral lateral malleolus and the seventh thoracic vertebra (T7) (red square). The three-dimensional inertial sensor was attached to T7 (green square). Both sensors recorded three one-dimension data series: anterior–posterior (AP), mediolateral (ML), and vertical (VT) data series.

Motor performance measurement

A motion capture system (Locus 3D MA-300; Anima, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with eight infrared cameras was used at a sampling rate of 100 Hz. The markers were attached to the anatomical landmarks of each participant, namely the bilateral ankle at the lateral malleolus and the seventh thoracic vertebra (T7), and the three-dimensional (3D) spatial data of these markers were recorded. A 3D inertial sensor (WALKING MVP-RF8-HC, Microstone, Nagano, Japan) was also used, and the sensor was attached to the back of each participant at the T7 level using a vest (Fig. 3b). The inertial sensor recorded 3D acceleration data at a sampling rate of 200 Hz. The data analysis in this study was conducted via an in-house program running on MATLAB® R2021a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, United States). Heel contact events were determined using the spatial data series of the left lateral malleolus in the vertical direction. The heel contact events in the acceleration data series were detected using the peaks of the vertical acceleration data46. The distance in the mediolateral (ML) direction during each gait cycle was measured using 3D spatial data from T7 in the ML direction. Mean, SD, and coefficient of variation of the distance in the ML direction were calculated, and Fig. 4 describes the calculation method in this study.

Calculation method for distance in ML direction. The blue line shows an example of spatial data of T7 in the ML direction. The red dash line indicates the time points at the heel contacts of the left foot. In each gait cycle, right and left end positions were detected (A, C, E, G) and distances from one end to the next end (AB, CD, EF, GH) were calculated. Each of these distances was used to estimate the mean, SD, and coefficient of variation of the distance in the ML direction. ML, mediolateral; T7, the seventh thoracic vertebra. Rt, right; Lt, left.

LDS was calculated using the ML-direction acceleration data from T7 to assess the characteristics of the tandem gait task. LDS is estimated from the largest Lyapunov exponent (LyE), commonly using Rosenstein’s algorithm39,47,48. The LyE is an analytical technique used to assess dynamic stability or chaos in nonlinear dynamical data40 and has been applied to assess gait quality in previous studies39. As the acceleration data of the tandem gait were also nonlinear dynamic data, the LDS technique was considered applicable for this study. According to previous findings49,50,51,52, the acceleration data series were normalized, and the number of data points per stride was fixed as the number of average stride times prior to estimating the largest LyE. The estimation method used in this study is in accordance with previous studies48,53. State space reconstruction of the normalized acceleration data series were performed using standard embedding techniques.

where \(X\left(t\right)\) represents the \({d}_{E}\)-dimensional state vector, \(x\left(t\right)\) represents the normalized acceleration data at time \(t\), \(\uptau\) represents the reconstruction lag and \({d}_{E}\) represents the embedding dimension. The reconstruction lags and embedding dimensions were calculated using the average mutual information algorithm and the global false nearest neighbors algorithm54,55. From the results of these algorithms, 15 were used as the reconstruction lags, and six were used as the embedding dimension in this study. LyE represents the average exponential rate of divergence of neighboring trajectories in the state space. The largest LyE (\({\uplambda }_{1}\)) can be estimated from:

where \(d(t)\) is the mean Euclidean distance between neighboring trajectories in the state space at time \(t\) and \(D\) is the initial average separation between neighboring points. Therefore, \({\uplambda }_{1}\) is defined in the dual limit as \(t \to \infty\) and \(D \to 0\) in Eq. (2). In Rosenstein’s algorithm, the largest LyE with finite-time data series (\({\uplambda }^{*}\)) is defined following Eq. (2) taking the log of both sides,

where \({d}_{j}(i)\) is the Euclidean distance between the \(j\)th pair of nearest neighbors after \(i\) discrete time steps (ex., \(i\Delta t\) seconds). The Euclidean distances between neighboring trajectories in the state space were calculated as a function of time and averaged over all the original pairs of nearest neighbors. The \({\uplambda }^{*}\) were estimated from the slopes of linear fits to curves defined by:

where \(\langle \bullet \rangle\) denotes the average overall values of \(j\). Estimates of \({\uplambda }^{*}\) were calculated over one stride as short-term exponents (\(\uplambda\) ST) and \(\uplambda\) ST was used as the parameter to represent LDS in this study.

Cognitive task: serial seven subtraction task and cognitive performance measurement

Serial subtraction tasks assess the working memory and attention of the participants and have been commonly used in previous studies on motor-cognitive dual-task paradigms56,57. In serial seven subtraction tasks, participants were required to repeatedly subtract seven from the first given number, and the number of correct answers was measured as cognitive performance. As described in the following section, cognitive performance was measured thrice in this study. The participants in each measurement were provided with a three-digit number by voice, subtracted seven times, and vocalized each answer in the 30-s task period. The three-digit numbers changed depending on the measurement (baseline: 532; pre-training: 712; post-training: 625). The voices of the participants were recorded using a voice recorder. Because the measurement time was set at 30 s, as described in the next section, the number of correct answers was measured to assess cognitive performance.

Experimental procedure

Figure 5 illustrates the experimental procedure used in this study. The participants in both groups followed identical procedures, except for the gait training section described below. As previously mentioned, a safety check for the minimum duration of the gait task was conducted at the beginning of the experimental procedure. Subsequently, all participants performed the cognitive task while sitting to measure their baseline cognitive performance after rehearsal. Performance measurements pre-training and post-training were conducted under two conditions: single-task (ST) and dual-task (DT). In the ST condition, the participants performed only the tandem gait task, and gait performance was measured for 30 s. In the DT condition, the participants performed the tandem gait task and the cognitive task simultaneously, and gait and cognitive performances were measured for 30 s. Given that task prioritization is known to affect task performance in dual-task conditions16, the participants were instructed to concentrate on the cognitive task as much as possible under DT conditions to match the task prioritization of each participant. The measurement order of the ST and DT conditions at both pre- and post-training was randomized among the participants.

Gait training sessions were performed five times consecutively to learn the tandem gait task. Each training session lasted for 1 min, and the rest sessions lasted for 30 s between training sessions. Our preliminary study indicated that more than five training sessions were difficult for older individuals due to fatigue. In the rest sessions, the participants took a break while standing on the treadmill. During the training sessions, participants in both groups were informed that the main purpose of the training sessions was to learn how to decrease postural perturbations during the tandem gait task. The difference between the IL and EL groups was that additional instructions were provided to each group. The participants in the IL group were instructed to “Walk as if you walk on a balance beam,” whereas the participants in the EL group were instructed to “Lift your toes to avoid stumbling” and “Move your weight smoothly from your rear foot to the other.” The participants in both groups were instructed to perform the tandem gait task according to the additional instructions. At the end of the experimental procedure, the participants were asked about the “knowledge of performance” of the tandem gait task acquired through the study. The question posed was, “Please describe your techniques or methods to perform the motor task. It doesn't matter how many answers you give.” Each participant completed the experimental procedure in a single day.

Measurements of dual-task cost

Dual-task cost (DTC) metrics have been used to assess dual-task interference, which indicates the amount of performance change under dual-task conditions as compared to single-task conditions17. Deterioration under the dual-task conditions was represented by a negative DTC value. Based on previous studies17,56,58, the DTC metrics used in this study were as follows:

For parameters for which higher values indicated worse performance (Mean, SD, and coefficient of variation of ML distance of T7 and LDS), a negative sign was inserted into Eq. (5), as follows:

In the gait parameters, DTCs were calculated using each gait parameter at pre-training or post-training respectively. For example, the DTC of the LDS at pre- and post-training was calculated as follows:

where \({DTC}_{LDS}\) represents the DTC of LDS, \({LDS}_{ST/DT}\) represents LDS under ST or DT conditions, and \(at Pre/Post\) represents measurement at pre- or post-training. Therefore, the DTCs of the gait parameters indicated how each parameter was affected by simultaneously performing the cognitive task pre- or post-training.

For the cognitive parameter, the DTC of the number of correct answers was calculated using baseline cognitive performance and cognitive performance at pre- and post-training as follows:

where \({DTC}_{Cog}\) represents the DTC of cognitive performance, \({N}_{CA}\) represents the number of correct answers, and \(at baseline\) represents being measured at the beginning of the experimental procedure as baseline cognitive performance. Therefore, the DTCCog indicated how cognitive performance was affected by simultaneously performing the gait task compared to the baseline performance measured while sitting.

Statistical analysis

A two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each parameters to reveal the training effect using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, United States), where the between-subjects factor (IL group vs. EL group) and within-subjects factor (Pre-training vs. Post-training) were used. Parameters in the ST condition and those in the DT condition were analyzed separately. Post-hoc analyses for the training effect were also performed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Welch’s t-test was employed to clarify the differences between the two groups regarding to the number of “knowledge of performance” in the gait task. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. Effect sizes were calculated using the G*Power 3.1.9.759. Since all analyses were exploratory, no power analysis was performed.

Data availability

The analysis code generated and used during the current study is available in the Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/sn7y4/).

References

Bayot, M. et al. The interaction between cognition and motor control: A theoretical framework for dual-task interference effects on posture, gait initiation, gait and turning. Neurophysiol. Clin. 48, 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucli.2018.10.003 (2018).

Pashler, H. Dual-task interference in simple tasks-data and theory. Psychol. Bull. 116, 220–244.https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.2.220 (1994).

Mihara, M. The relationship between cognitive decline and motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: a focused mini-review on cognitive-locomotor dual-task interference. Neurol. Clin. Neurosci. 8, 372–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncn3.12398 (2020).

McLeod, P. Parallel processing and the psychological refractory period. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 41, 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6918(77)90016-6 (1977).

Tombu, M. & Jolicoeur, P. A central capacity sharing model of dual-task performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 29, 3–18 (2003).

Muir-Hunter, S. W. & Wittwer, J. E. Dual-task testing to predict falls in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Physiotherapy 102, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.04.011 (2016).

Lundin-Olsson, L., Nyberg, L. & Gustafson, Y. “Stops walking when talking” as a predictor of falls in elderly people. Lancet 349, 617. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)24009-2 (1997).

Wajda, D. A., Motl, R. W. & Sosnoff, J. J. Dual task cost of walking is related to fall risk in persons with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 335, 160–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.09.021 (2013).

Plummer-D’Amato, P. et al. Training dual-task walking in community-dwelling adults within 1 year of stroke: a protocol for a single-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 12, 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-129 (2012).

Khan, M. J., Kannan, P., Wong, T. W., Fong, K. N. K. & Winser, S. J. A systematic review exploring the theories underlying the improvement of balance and reduction in falls following dual-task training among older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416890 (2022).

Zhang, X., Xu, F., Shi, H., Liu, R. & Wan, X. Effects of dual-task training on gait and balance in stroke patients: a meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692155221097033 (2022).

Wong, P. L., Cheng, S. J., Yang, Y. R. & Wang, R. Y. Effects of dual task training on dual task gait performance and cognitive function in individuals with Parkinson disease: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 104, 950–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2022.11.001 (2023).

Fritz, N. E., Cheek, F. M. & Nichols-Larsen, D. S. Motor- cognitive dual-task training in persons with neurologic disorders: A systematic review. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 39, 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0000000000000090 (2015).

Gallou-Guyot, M., Mandigout, S., Combourieu-Donnezan, L., Bherer, L. & Perrochon, A. Cognitive and physical impact of cognitive-motor dual-task training in cognitively impaired older adults: An overview. Neurophysiol. Clin. 50, 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucli.2020.10.010 (2020).

Ghai, S., Ghai, I. & Effenberg, A. O. Effects of dual tasks and dual-task training on postural stability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 12, 557–577. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S125201 (2017).

Yogev-Seligmann, G., Hausdorff, J. M. & Giladi, N. Do we always prioritize balance when walking? Towards an integrated model of task prioritization. Mov. Disord. 27, 765–770. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.24963 (2012).

Plummer, P. & Eskes, G. Measuring treatment effects on dual-task performance: A framework for research and clinical practice. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00225 (2015).

Liao, C. M. & Masters, R. S. Analogy learning: a means to implicit motor learning. J. Sports Sci. 19, 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410152006081 (2001).

Levin, M. F. & Demers, M. Motor learning in neurological rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 43, 3445–3453. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1752317 (2021).

Maier, M., Ballester, B. R. & Verschure, P. Principles of neurorehabilitation after stroke based on motor learning and brain plasticity mechanisms. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 13, 74. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2019.00074 (2019).

Kleynen, M. et al. Using a Delphi technique to seek consensus regarding definitions, descriptions and classification of terms related to implicit and explicit forms of motor learning. PLoS One 9, e100227. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100227 (2014).

Reber, A. S., Walkenfeld, F. F. & Hernstadt, R. Implicit and explicit learning: individual differences and IQ. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 17, 888–896 (1991).

Maybery, M., Taylor, M. & O’Brien-Malone, A. Implicit learning: sensitive to age but not IQ. Aust. J. Psychol. 47, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539508258763 (1995).

Lam, W. K., Maxwell, J. P. & Masters, R. S. Probing the allocation of attention in implicit (motor) learning. J. Sports Sci. 28, 1543–1554. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.517543 (2010).

Kim, S. M., Qu, F. & Lam, W. K. Analogy and explicit motor learning in dynamic balance: posturography and performance analyses. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 21, 1129–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1827046 (2021).

Lam, W. K., Maxwell, J. P. & Masters, R. S. W. Analogy versus explicit learning of a modified basketball shooting task: Performance and kinematic outcomes. J. Sports Sci. 27, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802448764 (2009).

Masters, R. S. W. Knowledge, knerves and know-how: The role of explicit versus implicit knowledge in the breakdown of a complex motor skill under pressure. Br. J. Psychol. 83, 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02446.x (1992).

Kleynen, M. et al. The immediate influence of implicit motor learning strategies on spatiotemporal gait parameters in stroke patients: A randomized within-subjects design. Clin. Rehabil. 33, 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518816359 (2019).

Lee, R. W. L., Tse, A. C. Y. & Wong, T. W. L. Application of analogy in learning badminton among older adults: Implications for rehabilitation. Motor Control 23, 384–397. https://doi.org/10.1123/mc.2017-0037 (2019).

Lam, W. K., Maxwell, J. P. & Masters, R. Analogy learning and the performance of motor skills under pressure. J. Sport Exercise Psychol. 31, 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.3.337 (2009).

Orrell, A. J., Eves, F. F. & Masters, R. S. Motor learning of a dynamic balancing task after stroke: Implicit implications for stroke rehabilitation. Phys. Ther. 86, 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/86.3.369 (2006).

Steenbergen, B., Van Der Kamp, J., Verneau, M., Jongbloed-Pereboom, M. & Masters, R. S. W. Implicit and explicit learning: Applications from basic research to sports for individuals with impaired movement dynamics. Disabil. Rehabil. 32, 1509–1516. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.497035 (2010).

Jie, L. J., Kleynen, M., Meijer, K., Beurskens, A. & Braun, S. Implicit and explicit motor learning interventions have similar effects on walking speed in people after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab017 (2021).

Dozza, M., Wall, C., Peterka, R. J., Chiari, L. & Horak, F. B. Effects of practicing tandem gait with and without vibrotactile biofeedback in subjects with unilateral vestibular loss. J. Vestib. Res. Equilibrium Orient. 17, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.3233/VES-2007-17405 (2007).

Tse, A. C. Y., Fong, S. S. M., Wong, T. W. L. & Masters, R. Analogy motor learning by young children: A study of rope skipping. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 17, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2016.1214184 (2017).

Woollacott, M. & Shumway-Cook, A. Attention and the control of posture and gait: A review of an emerging area of research. Gait Posture 16, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00156-4 (2002).

Lord, S. R. & Close, J. C. T. New horizons in falls prevention. Age Ageing 47, 492–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy059 (2018).

Stack, E. L. & Roberts, H. C. Slow down and concentrate: Time for a paradigm shift in fall prevention among people with Parkinson’s disease?. Parkinsons Dis. 1–8, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/704237 (2013).

Amirpourabasi, A., Lamb, S. E., Chow, J. Y. & Williams, G. K. R. Nonlinear dynamic measures of walking in healthy older adults: A systematic scoping review. Sensors (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/s22124408 (2022).

Mehdizadeh, S. The largest Lyapunov exponent of gait in young and elderly individuals: A systematic review. Gait Posture 60, 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.12.016 (2018).

Siragy, T. & Nantel, J. Quantifying dynamic balance in young, elderly and parkinson’s individuals: A systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci. 10, 387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00387 (2018).

Ekizos, A., Santuz, A., Schroll, A. & Arampatzis, A. The Maximum Lyapunov exponent during walking and running: Reliability assessment of different marker-sets. Front. Physiol. 9, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01101 (2018).

Frank, N. S., Prentice, S. D. & Callaghan, J. P. Local dynamic stability of the lower extremity in novice and trained runners while running intraditional and minimal footwear. Gait Posture 68, 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.10.034 (2019).

Shumway-Cook, A. & Horak, F. B. Assessing the influence of sensory interaction of balance. Suggestion from the field. Phys. Ther. 66, 1548–1550. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/66.10.1548 (1986).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012 (2020).

Wada, S. et al. Analysis of characteristics required for gait evaluation of patients with knee osteoarthritis using a wireless accelerometer. Knee 32, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2021.07.002 (2021).

Rosenstein, M. T., Collins, J. J. & De Luca, C. J. A practical method for calculating largest Lyapunov exponents from small data sets. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenomena 65, 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(93)90009-p (1993).

Dingwell, J. B. & Cusumano, J. P. Nonlinear time series analysis of normal and pathological human walking. Chaos 10, 848–863. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1324008 (2000).

Bruijn, S. M., van Dieën, J. H., Meijer, O. G. & Beek, P. J. Is slow walking more stable?. J. Biomech. 42, 1506–1512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.03.047 (2009).

Bruijn, S. M., van Dieën, J. H., Meijer, O. G. & Beek, P. J. Statistical precision and sensitivity of measures of dynamic gait stability. J. Neurosci. Methods 178, 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.12.015 (2009).

Cignetti, F., Decker, L. M. & Stergiou, N. Sensitivity of the Wolf’s and Rosenstein’s algorithms to evaluate local dynamic stability from small gait data sets. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40, 1122–1130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-011-0474-3 (2012).

Raffalt, P. C., Kent, J. A., Wurdeman, S. R. & Stergiou, N. Selection procedures for the largest Lyapunov exponent in gait biomechanics. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 47, 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-019-02216-1 (2019).

Dingwell, J. B., Cusumano, J. P., Cavanagh, P. R. & Sternad, D. Local dynamic stability versus kinematic variability of continuous overground and treadmill walking. J. Biomech. Eng. 123, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1336798 (2001).

Fraser, A. M. Using Mutual Information to Estimate Metric Entropy. In Dimensions and Entropies in Chaotic Systems 82–91 (Springer, 1986).

Kennel, M. B., Brown, R. & Abarbanel, H. D. Determining embedding dimension for phase-space reconstruction using a geometrical construction. Phys. Rev. A 45, 3403–3411. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.45.3403 (1992).

Pike, A., McGuckian, T. B., Steenbergen, B., Cole, M. H. & Wilson, P. H. How reliable and valid are dual-task cost metrics? A meta-analysis of locomotor-cognitive dual-task paradigms. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 104, 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2022.07.014 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Psychometric properties of dual-task balance and walking assessments for individuals with neurological conditions: A systematic review. Gait Posture 52, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.11.007 (2017).

Baek, C. Y. et al. Effects of dual-task gait treadmill training on gait ability, dual-task interference, and fall efficacy in people with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab067 (2021).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 (2009).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: RN, TO; Methodology: RN, SF, TO; Formal analysis and investigation: RN, TO; Resources: HI, SF, TO; Visualization: RN, TO; Supervision: HI, SF, TO; Writing – original draft: RN; Writing – review & editing: RN, HI, SF, TO.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishimoto, R., Inokuchi, H., Fujiwara, S. et al. Implicit learning provides advantage over explicit learning for gait-cognitive dual-task interference. Sci Rep 14, 18336 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68284-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68284-z