Abstract

Although there is consensus among dentists that visual aids not only improve vision but also help improve posture, evidence is scarce. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of visual aids (loupe and microscope) on the muscle workload of dentists during crown preparation on dentiform first molars in each quadrant of a phantom head, considering dentists’ muscles, patients’ tooth positions and surfaces. Six right-handed dentists from a single tertiary hospital participated. Surface electromyography device recorded the muscle workload of the bilateral upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, cervical erector spinae, and anterior deltoid during crown preparation. The results showed significantly lower workload in all examined muscles when using a microscope compared to the naked eye (p < 0.05), whereas the loupe showed reduced workload in some specific muscles. The muscle with the highest workload for all visual aids was the cervical erector spinae, followed by the upper trapezius. When analyzed by tooth surface, while the loupe did not significantly reduce overall workload compared to the naked eye for each surface, the microscope significantly reduced workload for most surfaces (p < 0.05). Therefore, during crown preparation, the workload of the studied muscles can successfully be reduced with the use of a loupe or microscope.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In order to gain precise vision inside small and dark working field, the patient’s mouth, it is unavoidable for dentists to work in a forward head posture, with the neck tilted forward and shoulders drooping forward in a rounded position1. This unbalanced posture leads to a high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists2. Over 60% of dentists suffer from various musculoskeletal disorders throughout their work life, mostly in the neck, shoulder, and back3. Many studies show that this disorder is prevalent since dental pre-clinical training periods. According to a study, approximately 85% of dental students reported experiencing a musculoskeletal disorder in at least one body region, with the neck being the most commonly affected area4. Therefore, several past studies emphasize the importance of implementing preventive strategies against musculoskeletal disorders in dentists. These strategies include alternating between standing and sitting5, increasing physical activity6, engaging in stretching exercises7, taking regular rest breaks8, and utilizing visual aid9. As for the use of visual aids, there is more focus on improving the success rate of dental treatments through enhanced vision10 than its benefits regarding enhanced posture. Although visual aids have also been highly recommended during dental treatment in order to enhance working posture and thus reduce muscle workload, there is a noticeable lack of substantial evidence supporting their ergonomic effectiveness.

In order to evaluate dentists’ working posture, multiple outcome measures are applicable, such as postural assessment11, pain scales12, and muscle activity monitoring13,14. Surface electromyography (sEMG) is a non-invasive technique that quantitively acquires electrical activities from surface muscles related to muscle contraction. It is utilized for measuring muscle workload, detecting muscle fatigue, and assessing the timing of muscular contractions15. Currently, it is employed in various fields such as research, rehabilitation, sports, and ergonomic industry16. To date, several studies have examined the effect of visual aids on ergonomics in dentistry using sEMG, with a particular focus on loupes. These studies have weighted their emphasis particularly on investigating the impact of different magnification levels (2.5× , 3.0× , and 3.5×) of Galilean loupes on working posture17, and also on the impact of using an ergonomic stool with or without loupes18. So far, no previous study has investigated the effect of dental microscope on working posture during dental treatment.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of visual aids (loupe and dental microscope) on muscle workload during crown preparation. This evaluation is conducted according to various factors: muscle (bilateral upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid (SCM), cervical erector spinae, and anterior deltoid), tooth position (#16, #26, #36, and #46), and tooth surface (occlusal, buccal, lingual/palatal, and proximal).

Results

A total of 288 mean %MVIC data points were obtained from the four surfaces of four teeth (#16, #26, #36, and #46) for the three types of visual aids (naked eye, loupe, and microscope) from six participants. The mean age of the participants was 32.3 ± 9.6 years. The normality tests indicated that the majority of values conformed to normal distribution.

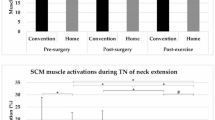

Influence of visual aid according to muscle for all four first molars

As shown in Table 1, the muscle workload of all muscles differed significantly among the three types of visual aid (p < 0.05). During crown preparation without the help of any visual aids, the order of mean %MVIC in descending order was cervical erector spinae > upper trapezius > SCM > anterior deltoid. Overall, compared to working with the naked eye, the workload of every muscle reduced when using a loupe but the difference was significant only for Lt. trapezius and bilateral SCM (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the use of a microscope resulted in reduced %MVIC with statistical differences for each of the other method for virtually every muscle (p < 0.05).

Influence of visual aid according to muscle for #16

Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 show the mean %MVIC of each muscle for each tooth position according to different visual aids. Regarding #16, as shown in Table 2, most of the muscles showed significant differences according to visual aids (p < 0.05). The order of muscle workload was Lt. erector spinae > Rt. erector spinae > Rt. upper trapezius > Lt. SCM without the use of any visual aid, where Lt. erector spinae was the significantly highest (p < 0.05). The mean %MVIC of these muscles were all reduced with the help of a microscope although the reduction was not statistically significant for Rt. erector spinae. Even with the use of a microscope, Lt. erector spinae remained to be the muscle with highest mean %MVIC followed by Rt. erector spinae but without significant difference between them. Meanwhile, working with a loupe did not have a significant impact on muscle workload of all muscles (p > 0.05).

Influence of visual aid according to muscle for #26

The mean %MVIC of each muscle during crown preparation of #26 according to different visual aids is compared in Table 3. Except for Rt. anterior deltoid, there were significant differences in mean %MVIC according to visual aid (p < 0.05), particularly between naked eye and microscope. Considering the mean %MVIC of all the muscles, statistical differences was noted between naked eye and loupe (p = 0.027), even though post hoc analysis revealed no significant difference according to a specific muscle. Similar to #16, although in slightly different order, the muscle with the highest workload during crown preparation with the naked eye was Lt. erector spinae followed by Rt. upper trapezius and Rt. erector spinae.

Influence of visual aid according to muscle for #36

Significant differences were observed between working with naked eye and microscope for Lt. upper trapezius, Rt SCM. And Rt erector spinae for #36 (p < 0.005, Table 4). Moreover, significant differences were noted between the use of a loupe and naked eye for Lt. upper trapezius and Rt. SCM (p < 0.02). Without the use of magnification, the %MVIC according to muscle in descending order was Rt. erector spinae > Lt. upper trapezius > Rt. upper trapezius ≈ Lt. erector spinae. The muscle workload of Rt. erector spinae, which was the highest, showed significant difference only with the use of a microscope (p < 0.05). The workload of Lt. upper trapezius during crown preparation without visual aid was statistically different compared to that of loupe and microscope, presenting higher mean %MVIC (p < 0.02). No significant differences according to muscle was observed between loupe and microscope (p > 0.05).

Influence of visual aid according to muscle for #46

Considering crown preparation of #46 with the naked eye, mean %MVIC was highest for Rt. erector spinae, followed by Rt. upper trapezius and Lt. erector spinae (Table 5). Significant differences were found between Rt. erector spinae and Lt. erector spinae (p < 0.05). Using a loupe, the order changed to Rt. erector spinae > Lt. erector spinae > Rt. upper trapezius, but without significant difference. Workload of bilateral upper trapezius, Rt. erector spinae, and Rt. anterior deltoid showed significant difference only with the use of a microscope (p < 0.03).

Summary of the influence of visual aid according to muscle and tooth position

As seen in Table 6, the majority of significant differences was observed between the naked eye and microscope, and this finding was dominant during crown preparation of #26 (p < 0.05). Meanwhile statistical difference between naked eye and loupe was observed in the mandibular first molars (#36 and #46) while statistical differences in muscle workload between loupe and microscope was observed in the maxillary first molars (#16 and #26). As for muscle, the muscles that were the least affected according to visual aid were bilateral anterior deltoids, and the most frequently affected was Rt. erector spinae.

Comparison of muscle workload according to tooth position

When evaluated according to tooth position (#16, #26, #36, and #46), no significant differences in mean %MVIC of each muscle were detected (Supplementary Table S1). Although not significant (p = 0.051), substantial difference was noted for Lt. upper trapezius between #16 and #36, with higher muscle workload during crown preparation of tooth #36.

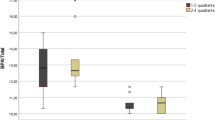

Influence of visual aid according to tooth surface

Figure 1 illustrates the mean %MVIC of the studied muscles according tooth surface of each tooth. Detailed values corresponding to Fig. 1 are shown in Supplementary Table S2. When evaluated according to tooth surface, significant differences are observed mostly between the naked eye and microscope (p < 0.05), with lower %MVIC with the use of a microscope. These findings were observed especially for maxillary first molars (#16 and #26). Furthermore, regardless of tooth position, muscle workload during crown preparation of the proximal surface was significantly reduced with the help of a microscope compared to working with the naked eye (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Previous studies that evaluate the effect of magnification have focused on the effect of loupes on muscle workload of dentists during class I cavity preparations19, periodontal probing20, and tooth drilling, filling and polishing for composite resin restorations18,21. No study that has assessed the use of microscope during crown preparation was noted. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the effect of not only loupe but also microscope on muscle workload during crown preparation.

In this study, compared to working with the naked eye, the muscle workload of most muscles was reduced with the use of a loupe (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). This finding is in accordance with a recent study that found that the use of a Galilean loupe resulted in lower muscle activity in the neck and back regions (trapezius and SCM) as well as less angular deviations of the neck and trunk during Class I cavity preparations22. The assumed ergonomic benefits of loupes can be attributed to the fixed working distance due to magnification and the declination angles20,23. These two characteristics render the operator free to move yet forced to stay relatively in a less forward-flexion neck position and thereby reduce the workload for neck and back muscles. The positive impact of declination angle on posture is stressed in previous articles. Loupes that allow a steeper declination angle allow the operator to work in a more neutral position25. However, in this study there were some exceptions where the use of a loupe instead resulted in higher muscle workload compared to working with the naked eye, although the difference was not significant. This may be because two participants of this study do not routinely use loupe in clinic, and thus were unfamiliar with its use. Since only six participants were involved in this study, it can be assumed that their outranging values had a considerable effect on the results.

Most of the significant differences in mean %MVIC were dominantly observed between naked eye and microscope according to muscle (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). Compared to loupes, microscopes allow higher magnification levels and further constrains flexion and rotation of the operator’s neck. One major difference from loupes is that it is not worn and almost every component of the microscope is adjustable in order to allow the operator to work at the most erect posture with minimal range of movement. For example, most have extendable binoculars and left/right swivel of the main body enables the operator to tilt the microscope in a vertical angulation without altering the horizontal level of the eyepieces. These characteristics allow the operator to work in a more erect position, especially of the neck.

Significant differences in muscle workload between the naked eye and loupe was only observed for mandibular first molars (Tables 5 and 6), whereas significant differences between loupe and microscope was only seen for maxillary molars (Tables 2 and 3). A possible explanation for this could be that since mandibular molars are further from the eyes, it is likely that the operator will lean more forwards for better vision during treatment without visual aid resulting in the greater enhancement of posture with the use of a loupe. On the other hand, during crown preparation of maxillary molars, dentists should tilt their heads to the right and rotate them to the left side while adopting a forward-head posture. In this situation, using a microscope may be more effective in reducing muscle workload compared to using a loupe.

Evaluating according to muscle, the results of this study showed that the mean %MVIC of cervical erector spinae, upper trapezius, and SCM differed significantly among the three types of visual aid. During crown preparation with the naked eye, the muscles with the highest workload was cervical erector spinae and upper trapezius regardless of tooth type. This is an anticipated result as dental treatments require the operator to be in a forward-head posture, forward flexion and rotation of the cervical spine, as well as slight elevation of the scapula in order to gain vision and access to the patient’s teeth which is located lower, in front of the operator.

Although statistical differences for the cervical erector spinae muscle was observed according to visual aids, it remained to be the muscle with the highest workload irrespective of visual aid and tooth type. According to a systematic review, although dental loupes enhance working posture and relieves shoulder and arm pain, their effect on neck pain is scarce26. The neck muscles observed in this study were the cervical erector spinae and SCM. The role of the erector spinae may account for its greater muscle activity. A major function of the cervical erector spinae is to support the head when it deviates forward or to the side, away from the body's center of gravity. Even though the use of visual aids can reduce the amount of neck flexion, absolute neutral position is virtually impossible, even with the help of a microscope. The approximate degree of the axis of cervical spine during crown preparation can be estimated to be 60° without the use of any visual aid, 45° when using a loupe, and 15° when using a microscope. Assuming the head is approximately 5 kg at neutral position, these positions exert forces of 27.2 kg, 22.2 kg, and 12.2 kg to the cervical spine, respectively24. Therefore, to prevent neck pain, implementing additional strategies like stretching and scheduling regular breaks may be beneficial.

When treating the maxillary first molars (#16 and #26) the muscle workload of the left erector spinae was higher than the right side (Tables 2 and 3), and vice versa when treating the mandibular first molars (#36 and #46) (Tables 4 and 5). This may be due to the fact that because right-handed dentists usually work on the right side of the patient, gaining vision to the maxillary teeth requires more rotation of the head to the left side which requires more workload for the left erector spinae, than the right. Meanwhile, during the preparation of mandibular molars, the cervical spine is required to be flexed laterally to the left while maintaining a forward-flexed posture. Consequently, to prevent the head from dropping, the right erector spinae must be activated, in order to help align the head closer to the body's center of gravity. However, this explanation cannot be generalized as the preferred position during dental treatment varies greatly among dentists and depends on whether a direct view or a mirror view is used.

As demonstrated in Table 6, the muscle that was the least influenced by visual aid was anterior deltoid. However, the fact that the anterior deltoid muscle did not show significant difference according to visual aid may be attributed to its relatively low mean %MVIC. Since the function of anterior deltoid is flexion as well as internal rotation of the arm, this muscle may not be routinely used during crown preparation. Moreover, given that the distance between the patient and dentist doesn't vary greatly, there is minimal likelihood of needing to significantly flex the shoulders throughout the procedure. This finding is consistent with results from a previous study that found significant improvements in the positions of the head and neck but not in the arms, when using loupes as compared to those working with unaided eyes23.

No significant difference in muscle workload was found according to tooth position (Supplementary Table S1). However, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution because the average of the mean %MVIC of all types of visual aids was used for analysis. Therefore, the low muscle activities during crown preparation using a microscope might have masked the differences according to tooth type.

Evaluating from tooth surface factor (Fig. 1), significant differences in overall muscle workload was noted between the naked eye and microscope during crown preparation of the proximal surface of every tooth position (p < 0.05). This implies that with the help of a microscope, muscle workload can be reduced substantially regardless of tooth type when performing crown preparation of the proximal surface. Taking into account that the proximal surface is often considered as the most strenuous surface to work on, this finding could potentially reduce the physical strain for dentists.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, since the crown preparations were conducted on a phantom, they do not accurately replicate clinical conditions, such as the presence of the patient’s tongue and cheek, which could lead to an underestimation of the results. Secondly, given the relatively small field of view offered by microscopes, frequent adjustments might be required during actual crown preparations in patients, which may potentially result in a higher muscle workload than what was observed in this study. Furthermore, as this study did not assess the quality of the crown preparations, a comparison of preparation quality based on the type of visual aid used is also required. Lastly, considering that posture during crown preparation can vary significantly among operators, studies involving a larger number of participants appear to be necessary.

As a conclusion, the muscle workload of bilateral upper trapezius, cervical erector spinae, and sternocleidomastoid differed significantly according to type of visual aid. Within the limitation of this study, although significant differences in the muscle workload of cervical erector spinae was observed, it remained to be the muscle with the highest workload. Moreover, implementing a microscope for crown preparation may be helpful in reducing muscle workload by enabling the dentist to work in a more upright posture.

Methods

Participants

Six dentists from a Department of Conservative Dentistry in a single tertiary hospital participated in this pilot study. The inclusion criterion was right-handed dentists without any self-reported musculoskeletal pain. After a thorough explanation of the purpose and the procedures of this study, written informed consent was obtained. The study protocol was approved by the relevant institutional review board (3-2022-0272) and complied with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of the World Medical Association.

Gold crown preparation procedures

Gold crown preparations were performed on artificial first molars in each quadrant, including the maxillary right first molar, maxillary left first molar, mandibular right first molar, and mandibular left first molar. A 3-min break was given between each crown preparation. All participants performed four crown preparations without any visual aids (naked eye), using a Galilean loupe of their own with 2.5× magnification (EyeMag® Smart, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany or SurgeLoup®, Crystal Optic, Incheon, South Korea), and using a dental microscope under 4.0× magnification (OPMI® pico, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

The procedures were performed on a phantom (Mannequin trunk type, Nissin, Kyoto, Japan) that was placed on a dental chair (Intego, Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) in order to simulate treatment in a clinical setting. A new 102R diamond bur (Shofu inc., Kyoto, Japan) was given to each participant. The participants were allowed to adopt their usual treatment posture and adjust the position of the phantom. All treatment was performed with direct view and the dental mirror was used for retraction when needed.

Muscle workload measurement

Surface electromyographic signals were recorded with FreeEMG 1000 8ch (BTS Bioengineering, Milano, Italy) and the wireless, Bluetooth-based electrodes were placed with an inter-electrode distance fixed at 2 cm, parallel to the muscle fibers, at the locations described in Table 7. The skin was prepped by cleansing the electrode placement area with an alcohol swab. For each tooth, the sEMG data was collected separately, according to tooth surface; occlusal, buccal, lingual/palatal, and proximal. The sEMG signal was recorded for 90 s for each tooth surface, followed by a rest time of 90 s in order to prevent fatigue. The initial and final 30 s of the obtained EMG signal was discarded and the middle 30 s was used for analysis.

Before crown preparation, in order to normalize the data obtained, each participant performed three trials of resisted maximum voluntary isometric contractions (MVICs) for 3 s with 20 s of recovery break between each trial for each measured muscle. For upper trapezius, the participants elevated their shoulders with maximum strength while manual pressure in the opposite direction strong enough to maintain isometric contraction was applied by the examiner. Lateral flexion of the neck for SCM, extension of the neck cervical erector spinae, and abduction of the arm for anterior deltoid was performed in the same way. The mean MVIC of the three trials was used for analysis. The participants rested for 10 min before commencing the experimental procedure.

Muscle workload data for each muscle obtained from the electrodes were analyzed using EMG Analyzer (BTS Bioengineering, Milano, Italy). The sampling rate was 1,000 Hz and the raw EMG data were processed using the root mean square (RMS) with 50 ms and 20–500 Hz filter. The EMG measurements converted to the percentage of MVIC (% MVIC) was used for comparison in this study, as shown in Eq. (1).

Statistical analysis

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Shapiro–Wilk test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test for the normality of data distribution. ANOVA was used to determine the differences of %MVIC among different types of visual aids (naked eye, loupe, microscope) and muscle (bilateral upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, cervical erector spinae, and anterior deltoid) according to tooth position (#16, #26, #36, and #46). Significant differences in muscle workload according to tooth position and the effect of visual aid according to tooth surface (occlusal, buccal, lingual/ palatal, and proximal) was also examined. Bonferroni correction was applied for the p-value of post-hoc analysis (p < 0.05).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Gangnam Severance Hospital (IRB No.: 3-2022-0272).

Data availability

Data for the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mansoor, S. N., Al Arabia, D. H. & Rathore, F. A. Ergonomics and musculoskeletal disorders among health care professionals: Prevention is better than cure. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 72, 1243–1245. https://doi.org/10.47391/jpma.22-76 (2022).

Cherniack, M. G., Dussetschleger, J. & Bjor, B. Musculoskeletal disease and disability in dentists. Work 35, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-2010-0978 (2010).

Pejcić, N., Jovicić, M., Miljković, N., Popović, D. B. & Petrović, V. Posture in dentists: Sitting vs. standing positions during dentistry work–An EMG study. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 144, 181–187 (2016).

Ng, A., Hayes, M. J. & Polster, A. Musculoskeletal disorders and working posture among dental and oral health students. Healthcare (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4010013 (2016).

Valachi, B. & Valachi, K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: Strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 134, 1604–1612. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106 (2003).

Thakar, S. et al. High levels of physical inactivity amongst dental professionals: A questionnaire based cross sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9, ZC43–ZC46. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2015/10459.5466 (2015).

Kumar, D. K. et al. Exercise prescriptions to prevent musculoskeletal disorders in dentists. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 8, 13–16. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2014/7549.4620 (2014).

Pope-Ford, R. & Jiang, Z. Neck and shoulder muscle activation patterns among dentists during common dental procedures. Work 51, 391–399. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-141883 (2015).

Lietz, J., Ulusoy, N. & Nienhaus, A. Prevention of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals through ergonomic interventions: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103482 (2020).

Floratos, S. & Kim, S. Modern endodontic microsurgery concepts: A clinical update. Dent. Clin. North Am. 61, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2016.08.007 (2017).

Dable, R. A. et al. Postural assessment of students evaluating the need of ergonomic seat and magnification in dentistry. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 14, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13191-014-0364-0 (2014).

Hayes, M. J., Osmotherly, P. G., Taylor, J. A., Smith, D. R. & Ho, A. The effect of loupes on neck pain and disability among dental hygienists. Work 53, 755–762. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-162253 (2016).

De Bruyne, M. A. et al. Influence of different stool types on muscle activity and lumbar posture among dentists during a simulated dental screening task. Appl. Ergon. 56, 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2016.02.014 (2016).

Haddad, O., Sanjari, M. A., Amirfazli, A., Narimani, R. & Parnianpour, M. Trapezius muscle activity in using ordinary and ergonomically designed dentistry chairs. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 3, 76–83 (2012).

Strimpakos, N., Georgios, G., Eleni, K., Vasilios, K. & Jacqueline, O. Issues in relation to the repeatability of and correlation between EMG and Borg scale assessments of neck muscle fatigue. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 15, 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.01.007 (2005).

Tapanya, W., Puntumetakul, R., Neubert, M. S., Hunsawong, T. & Boucaut, R. Ergonomic arm support prototype device for smartphone users reduces neck and shoulder musculoskeletal loading and fatigue. Appl. Ergon. 95, 103458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103458 (2021).

Pazos, J. M., Regalo, S. C. H., de Vasconcelos, P., Campos, J. & Garcia, P. Effect of magnification factor by Galilean loupes on working posture of dental students in simulated clinical procedures: Associations between direct and observational measurements. PeerJ 10, e13021. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13021 (2022).

López-Nicolás, M. et al. Effect of different ergonomic supports on muscle activity of dentists during posterior composite restoration. PeerJ 7, e8028. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8028 (2019).

Pazos, J. M., Wajngarten, D., Dovigo, L. N. & Garcia, P. Implementing magnification during pre-clinical training: Effects on procedure quality and working posture. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 24, 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12517 (2020).

Branson, B. G., Abnos, R. M., Simmer-Beck, M. L., King, G. W. & Siddicky, S. F. Using motion capture technology to measure the effects of magnification loupes on dental operator posture: A pilot study. Work 59, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-172681 (2018).

García-Vidal, J. A. et al. The combination of different ergonomic supports during dental procedures reduces the muscle activity of the neck and shoulder. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081230 (2019).

Pazos, J. M. et al. Magnification in preclinical procedures: Effect on muscle activity and angular deviations of the neck and trunk. PeerJ 12, e17188. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17188 (2024).

Carpentier, M. et al. The effect of magnification loupes on spontaneous posture change of dental students during preclinical restorative training. J. Dent. Educ. 83, 407–415. https://doi.org/10.21815/jde.019.044 (2019).

Hansraj, K. K. Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg. Technol. Int. 25, 277–279 (2014).

Voruganti, K. Practice dentistry pain-free: Evidence-based strategies to prevent pain and extend your career. Br. Dental J. 206, 181–181. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.73 (2009).

Plessas, A. & Bernardes Delgado, M. The role of ergonomic saddle seats and magnification loupes in the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders. A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 16, 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/idh.12327 (2018).

Holtermann, A. et al. Selective activation of neuromuscular compartments within the human trapezius muscle. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 19, 896–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.04.016 (2009).

Kilinc, H. E. & Ünver, B. Effects of craniocervical flexion on suprahyoid and sternocleidomastoid muscle activation in different exercises. Dysphagia 37, 1851–1857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10453-1 (2022).

Caneiro, J. P. et al. The influence of different sitting postures on head/neck posture and muscle activity. Man. Ther. 15, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2009.06.002 (2010).

Netto, K. J. & Burnett, A. F. Reliability of normalisation methods for EMG analysis of neck muscles. Work 26, 123–130 (2006).

Szeto, G. P., Straker, L. M. & O’Sullivan, P. B. A comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic office workers performing monotonous keyboard work–1: Neck and shoulder muscle recruitment patterns. Man. Ther. 10, 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2005.01.004 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the participants of this study for their important contributions and Sunung Yun for his help with the use of FreeEMG 1000 8ch (BTS Bioengineering, Milano, Italy).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: S. Hong, J.W. Park, J. Park; Acquisition and analysis of data: S. Hong, J.W. Park, J. Park; Drafting the manuscript or figures: S. Hong, J.W. Park, S.J. Shin, M.J. Jeon, J. Park, J.H. Park. S. Hong and J. Park contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, S., Park, J., Jeon, MJ. et al. Effect of loupe and microscope on dentists’ neck and shoulder muscle workload during crown preparation. Sci Rep 14, 17489 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68538-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68538-w

This article is cited by

-

The effect of dental loupes on postural ergonomics during non-surgical periodontal therapy

Scientific Reports (2025)