Abstract

Within the scope of this investigation, we carried out experiments to investigate the potential of the Vision Transformer (ViT) in the field of medical image analysis. The diagnosis of osteoporosis through inspection of X-ray radio-images is a substantial classification problem that we were able to address with the assistance of Vision Transformer models. In order to provide a basis for comparison, we conducted a parallel analysis in which we sought to solve the same problem by employing traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which are well-known and commonly used techniques for the solution of image categorization issues. The findings of our research led us to conclude that ViT is capable of achieving superior outcomes compared to CNN. Furthermore, provided that methods have access to a sufficient quantity of training data, the probability increases that both methods arrive at more appropriate solutions to critical issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep learning is a specific branch of machine learning that use artificial neural networks (ANNs) to acquire knowledge from extensive datasets and execute intricate operations1. Artificial neural networks are computational models that draw inspiration from the structure and functionality of real neurons. They are composed of interconnected nodes organized into layers, which collectively interpret information that is transmitted to subsequent levels. The nodes inside each layer possess varying characteristics, such as similarities, architectures, operations, and parameters, which are contingent upon the specific job and dataset at hand. The parameters are typically initialized in a random manner and subsequently changed via a process known as learning or training.

While the concept of deep learning dates back to the 1980s, it has only been in recent years that it has seen widespread adoption and success thanks to advances in large data, processing power, and algorithm development. Computer vision, natural language processing (NLP), speech recognition, recommender systems, autonomous vehicles, and many more challenges have all benefited from the use of deep learning. Image production, machine translation, game playing, and natural language understanding are other areas where deep learning has demonstrated meaningful outcomes.

Deep learning is not only transforming the fields of science and technology, but also the fields of art, culture, and society. Deep learning is creating new forms of art, including style transfer2, neural style3, and deep dream4, that all blend different styles and genres. Deep learning is creating new forms of culture, such as neural rap5, neural karaoke6, neural doodle7, that together combine different languages and expressions. Deep learning is creating new forms of society, such as social bots8, chatbots9, virtual assistants10, that interact with humans and other machines. Therefore, with deep learning advancements, a prospective revolution can be expected in the future of many scientific fields and medical sciences are no exception to that.

The field of medicine stands out as one where deep learning could have a significant and positive impact. Clinical and biomedical disciplines are concerned with all aspects of health care, including the identification, evaluation, and management of illness. Data of several kinds are used in the medical sciences, including medical pictures, electronic health records (EHRs), genome sequences, and pharmacological compounds. Detection, diagnosis, prognosis, prediction, classification, segmentation, generation, synthesis, are just a sampling of the many tasks that would benefit from objectivity and automation in the medical sciences.

Deep learning can provide excellent answers for numerous issues and opportunities in medical sciences. Using the strength of artificial neural networks (ANNs), deep learning can learn from raw or unstructured data with little to no feature engineering or preprocessing. Even without substantial dimensionality reduction or regularization, deep learning can handle large-scale or high-dimensional data. Deep learning can also learn new representations or functions that are highly abstract or sophisticated without requiring a large amount of training data or explicit assumptions11.

In medicine, deep learning has several potential uses and applications such as:

-

Diagnostic imaging: Medical imaging diagnostics can be performed using deep learning, which can interpret multiple biomedical image types such as X-rays, MRI scans, and CT scans. The algorithms are able to recognize any potential risk and highlight any abnormalities in the images. In the process of cancer detection, deep learning is used extensively. Machine learning and deep learning were the driving forces behind the recent breakthroughs in computer vision12,13.

-

Electronic health records: Deep learning allows for the analysis of electronic health records (EHRs) that include both structured and unstructured data, such as clinical notes, laboratory test results, diagnoses, and prescriptions, at remarkable speeds while maintaining the highest possible level of accuracy. Additionally, mobile devices such as smartphones and wearable technology offer valuable information regarding patient behaviors and mobility. These devices have the capability of transforming data through the use of mobile applications to monitor medical risk factors for deep learning models14.

-

Genomics: The analysis of genomic sequences, which yields information about genotype/phenotype correlations and evolution of organisms, can be performed by deep learning. The identification of genes that are associated with diseases or traits can be assisted by deep learning. Recent studies show that deep learning can also aid in the design of novel genes or the editing of existing genes for therapeutic purposes.

-

Drug development: Regarding the pharmaceutical industry, deep learning can aid in both the development of new pharmacotherapies and the improvement of existing ones. Drug molecules with the appropriate properties or functionalities can be designed with the use of deep learning. Predicting drug interactions and adverse effects is another area where deep learning has proven useful15,16.

The aforementioned uses represent only a minor fraction (the proverbial ‘tip of the iceberg’) of what deep learning algorithms can accomplish and potential contribute to the broader field of medical image analysis. Deep learning has been remarkably successful in medical image analysis, and this achievement has coincided with a period of drastically expanded utilization of electronic medical records and diagnostic imaging. With deep learning, significant hierarchical linkages within the data can be discovered algorithmically, rather than through the time-consuming manual construction of features, and hierarchical linkage algorithms are very helpful in the era of biomedical big data.

Examples of important work in the field of deep learning-based medical image analysis include:

-

Image classification: Classifying medical images into appropriate groups

-

Localization: Pinpointing an object in an image

-

Detection: Identifying instances of predefined semantic objects in digital media.

-

Segmentation: Partitioning digital images into numerous segments so that they can be simplified and/or their representation can be altered to make them more meaningful and easier to evaluate

-

Registration: Aligning or generating correspondences between data. Mapping one image to another is one such example17,18.

Medical image analysis using a Deep Learning Approach (DLA) is a rapidly expanding area of study. DLA has seen extensive usage in medical imaging for illness diagnosis. This method, which relies on a convolution process, has effectively been applied in the field of medical visual pattern identification. Insightful studies of DLA and progress in artificial neural network development have yielded intriguing applications in medical imaging. One type of deep learning model referred to as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) has been successfully used in conjunction with backpropagation to carry out automatic recognition tasks19. In addition, the utilization of deep learning architectures has been observed in the context of data augmentation, specifically in the domain of medical picture augmentation. This practice involves the application of three distinct types of deep generative models, namely Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Deep Models (DMs)20.

Beyond the significant achievements and continued promise, progress in medical image processing using deep learning faces ongoing challenges, such as:

-

Data availability: The paucity of well-annotated large-scale datasets is a major obstacle to this line of study21. This is a typical problem in the field of medical imaging, where strict privacy and confidentiality regulations restrict access to patient information.

-

Adversarial attacks: Noisy medical imaging data presents a challenge for deep neural networks and designs.

-

Trustability: Users and patients may be hesitant to utilize deep learning technologies in healthcare due to concerns about validity and security.

-

Ethical and privacy issues: Ethical and privacy issues relating to medical data are also key challenges that need to be addressed22.

-

Data quality and variations: Variations in the quality of the data as well as the input present considerable issues. These differences can be the result of using different imaging methods, adjusting the scanner parameters, or moving the patient.

-

Overfitting: Deep learning models often have a propensity to overfit, which is especially problematic when there is a limited amount of training data available23.

Deep learning's transformative impact extends into the field of medical sciences, including the detection and diagnosis of osteoporosis, a condition characterized by weakened bones and an increased risk of fractures. Osteoporosis is a prevalent and debilitating condition, especially among the elderly, leading to significant morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Early diagnosis is crucial because it enables timely intervention, which can prevent fractures and their associated complications. Traditional methods of diagnosing osteoporosis, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), are effective but can be limited by accessibility and cost. X-ray imaging is more widely available and less expensive, making it a valuable tool for osteoporosis screening if enhanced by advanced diagnostic techniques.

Recent advancements have seen the integration of deep learning techniques, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of osteoporosis detection from X-ray images. These advanced models can automatically analyze X-ray images, identifying subtle patterns and variations indicative of osteoporosis with higher precision than traditional methods. By comparing ViTs and CNNs, researchers aim to determine the most effective approach for early and accurate osteoporosis diagnosis, potentially improving patient outcomes through timely and targeted treatment strategies. The early detection of osteoporosis using deep learning can facilitate preventive measures, such as lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and monitoring, thereby reducing the risk of fractures and improving the quality of life for patients. The application of deep learning in this area exemplifies its broader potential to revolutionize medical diagnostics and enhance the quality of healthcare, emphasizing the importance of innovative technologies in managing and curing osteoporosis.

CNN and ViT

In the realm of deep learning algorithms, convolutional neural networks are the most widely used tools for processing images. CNNs are artificial neural networks that are primarily used to solve difficult image-driven pattern recognition tasks. These networks represent very impressive forms of ANN architecture and a remarkable example of ANN design. CNNs consist of one or more convolutional layers, typically accompanied by pooling layers, fully connected layers, and normalization layers. A version of multilayer perceptrons is employed, which is specifically designed to require only limited preprocessing.

The architectural design of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) is specifically tailored to exploit the inherent 2D structure present in input images or other 2D inputs, such as speech signals. Translation invariant characteristics are obtained through the utilization of local connections and tied weights, followed by a pooling process. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) employ a comparatively minimal amount of pre-processing in comparison to alternative image categorization algorithms. This functionality implies that the network acquires the ability to learn and acquire filters that were previously required manual design in traditional techniques. The significant advantage of this functionality is the ability to achieve independence from pre-existing knowledge and human labor in the process of feature design. The nomenclature "convolutional neural network" reflects network utilization of distinct forms of linear operations that permit mathematical convolution. Convolutional neural networks employ convolution operations instead of conventional matrix multiplication in at least one of its layers24. Figure 1 is an illustration of CNN’s function.

An illustration of how a CNN block functions. Each CNN layer consists of several “filters”. Each filter can be represented as a n × n matrix of numbers which are learned during the training process. When the CNN layer operates on the image, at each step, which is called “stride” technically, that n × n matrix multiplied with the values of a n × n piece of the image and “summarize” that piece with a single number, as it can be seen in the figure. Then, the filter proceed one step and size of that further movement is equal to the “stride” parameter. The “parameter” makes sure that when the filter starts from the upper left corner of the image, the whole of it covers the image, namely, it simply add some pixels with the value of 0 to the borders of the image25.

CNNs have long been regarded as the predominant and uncontested algorithmic approach for image processing, until more recently. However, Vision Transformers (ViTs) are a recent advancement in computer vision that have been gaining prominence due to their potential to outperform CNNs on a number of different vision tasks. The self-attention mechanism is the essential idea that underpins the tremendous success of Vision Transformers. In contrast to CNNs, which focus largely on the nearby aspects of an image, ViTs are able to zero in on the long-distance connections that exist within the image. In comparison to CNNs, ViTs are endowed with greater versatility and capability of feature detection.

ViTs may be broken down into many transformer blocks, and within each of these blocks is both a self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward neural network. This makes up the ViT's architecture. A sequence of image patches serves as the input to a ViT, and these transformer blocks do their processing in tandem with one another26,27.

CNNs, on the other hand, have been the standard model for visual data for a considerable amount of time. They are made up of convolutional layers, which are then followed by pooling layers, and they are exceptionally good at finding local characteristics in images28. ViTs, on the other hand, excel in their ability to zero in on long-range associations within the image, but CNNs are incapable of doing so27.

ViTs and CNNs have both demonstrated outstanding outcomes in a variety of vision applications, despite the fact that they operate in quite different ways. For example, one study compared vision transformers and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in the field of digital pathology. The results showed that ViTs performed marginally better than CNNs for tumor detection in three out of four different types of tissue. ViTs, on the other hand, require a greater investment of time and effort to train than CNNs do, despite the fact that they have demonstrated results that are encouraging. In addition, in order for ViTs to outperform CNNs, the tasks that they are asked to complete may need to be made more difficult so that they may make the most of their limited inductive bias27. In Fig. 2 the function of ViT can be seen.

An overview of a ViT architecture. As it can be seen, ViT starts with “patching” the input images, i.e., dividing it to separate regions and feed them to its Attention mechanism29.

In this research, we used many ViT variants alongside several well-known CNN variants to solve a classification problem and then compared their results.

Osteoporosis and X-ray image classification

Resorption and deposition of new bone mineral balance adult bone mineral loss to maintain strength. Resorption lowers bone mineral density, making bones brittle and fracture-prone. Osteoporosis involves bone remodeling. Understanding bone remodeling regulation helps prevent and treat osteoporosis30,31. Architecture and geometry make bones light and strong. Long tubular bones have a strong cortical layer and softer trabecular bone. These strong, light, and flexible bones can handle high-impact exercises without breaking. Trabecular bone has a dense cortical layer like vertebrae. When loaded briefly, vertebrae compress and expand. Skeletons must grow, heal, and adapt. Bone remodeling matters. Daily remodeling leads the cortical layer to resorb minerals and the bone cavity to lose trabecular bone and grow as we age32. Some compensation comes from mineral layer growth outside the cortical layer. Continuous remodeling and bone microarchitecture strongly impact osteoporosis development (Fig. 3).

Young adults with wider femurs may fracture their hips later in life due to thinner cortical layers. Later resorption is more frequent in thinner layers. Monoclasts and mesenchymal osteoblasts from different cell lines affect bone resorption and deposition. Osteoclast cell membranes' very active ion channels release protons into the extracellular space to lower pH and break down bone33. This environment produces osteoclast-derived proteolytic enzymes such cathepsin K that remove bone matrix and induce mineral loss. Osteoblasts create amounts of collagen type I and negatively charged non-collagenous proteins to make hydroxyapatite, the major new bone material. Cell/cell communication between these two cell types controls bone synthesis, maintenance, and loss. Osteoclast activation begins bone resorption during remodeling. After a brief “reversal” period in the resorption “pit,” progressive waves of osteoblasts build new bone matrix. Since bone production takes longer than resorption, remodeling may cause bone loss34. To communicate, precursors, osteoclasts, and osteoblasts generate “signaling” molecules. Signaling chemicals, hormones, food, and exercise are being studied to change bone physiology cells. Multiple hormonal and endocrine factors tightly control bone growth and homeostasis. Bone growth and maintenance require estrogen, parathyroid hormone, and testosterone-converted estrogen. Bone cells are directly affected by estrogen via osteoblast and osteoclast receptors. This interaction starts a complex cell cycle that increases osteoblast activity and disrupts osteoblast-osteoclast communication. Bone resorption and formation are coordinated by osteoblasts activating osteoclasts35. Estrogen is delivered into the nucleus by the ERα cell surface receptor, activating certain genes. ERRα and ERα receptors in osteoblasts may govern bone cells. Recent evidence suggests SHBG, which lets estrogen enter cells, may also contribute. Natural estrogen reaches the bloodstream far from bone, affecting the uterus and breast. Other locally produced signaling molecules greatly affect bone physiology. In particular, PGE2 stimulates bone growth and resorption. Bone cells make PGE2 from arachidonic acid. In mechanically stressed animals, reducing prostaglandin production by COX2 enzymes slows bone development36. Exercise-induced bone growth may require PGE2. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory COX-2 drugs may increase fracture risk. Leukotrienes regulate bone remodeling. As osteoclasts and osteoblasts rebuild mouse bone, arachidonic acid-derived compounds diminish bone density37.

Outside bone cells use cell surface receptors to notify the cell nucleus to activate or deactivate activity-regulating genes. These contain BMP receptors, which boost bone growth. Osteoblast precursors have BMP receptors. As mice lacking LRP5 develop severe osteoporosis, the Wnt receptor low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-related protein 5 receptor (LRP5) may also be critical for bone formation. BMP receptors and LRP5 may stimulate osteoblasts, but how is unknown. Sclerostin binding to osteoblasts' LRP5/6 receptor suppresses Wnt signaling, reducing bone formation. PTH and mechanical stress lower osteoblast sclerostin. Sclerostin antibodies expand bone and strengthen it. The cell surface receptor RANK and its partner RANKL trigger precursor cells to become osteoclasts38,39,40. Bone-rebuilding osteoblasts and osteoclasts create various signaling molecules, including RANKL. An equilibrium between RANKL and osteoprotegerin causes osteoporosis. In animal studies, osteoprotegerin increases bone mass and loss causes osteoporosis and fractures. Human osteoporosis can be treated with RANKL inhibitors Table 1. The cell surface receptors DAP12 and FcRγ work together to assist in osteoclast development and activation. Mice lacking DAP12 and FcRγ exhibit severe osteoporosis, marked by increased bone density. Two cell surface receptors recruit ITAM adaptor proteins to increase intracellular calcium. Studies demonstrated RANK/RANKL and ITAM pathways activated osteoclasts. Both routes activate NFAT c1. To become active osteoclasts, precursor cells need NFATc1, which controls bone resorption. Environmental and genetic factors affect osteoblast and osteoclast gene expression and osteoporosis41,42,43.

Diagnosis

Seniors have increased osteoporosis risk. However, osteopenia or osteoporosis can begin earlier. Since osteoporosis has no symptoms, a complete medical history, including recent fractures, and risk factors (see risk factors and individuals at high fracture risk) should determine if a BMD test is warranted. Many healthcare systems recommend a fracture risk assessment before a BMD test. This is the most common BMD test method, but other diagnostic equipment gives more. The pathophysiological definition of osteoporosis includes diminished bone mass and other bone fragility characteristics as key risk factors for fractures. Bone mass alone predicts fracture risk in clinical practice. So, it can diagnose and track patients. Bone density/volume or area is BMD53.

Normal X-rays can only show spine fractures; hence BMD examinations require specific equipment. The most prominent BMD test is DXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry), a densitometric technique that can be measured in vivo and validated by many fracture risks studies. DXA uses hydroxyapatite (bone mineral) and soft tissue as reference materials to assess low-radiation X-ray beam attenuation through the body with two photon energies to detect tiny bone loss. Software detects bone edges. For osteoporosis risk, DXA is most commonly used to evaluate bone density in the proximal femur (including femoral neck) and lumbar spine (L1–L4). DXA is used to diagnose vertebral fractures using vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) and the trabecular bone score (TBS) using lateral spine images54,55.

WHO osteoporosis DXA scan thresholds. Z- or T-scores are SD-based. The proposed reference range uses NHANES III reference database femoral neck measures in Caucasian women aged 20–29 to calculate T-score. Osteoporosis is diagnosed when a person's femoral neck T-score for BMD is 2.5 SDs below the reference value, obtained from bone density measurements in young healthy females (see Table 2 and Fig. 4)56,57. Osteoporosis is usually diagnosed by lumbar spine T-score. Bone density data adjusted for age and sex yields the Z-score reference value. It displays how many SDs an individual's BMD must depart from the anticipated mean for his/her age and sex group. It's usually used to assess kids and teens58,59.

Comparing DXA results from the same patient scanned by different brands is risky since some manufacturers modify key parameters. These characteristics include voltages, filtering, edge detection, and soft tissue thickness. Consider scanning patients with the same equipment to compare results. Osteoporosis DXA bone density testing is quantitative, non-invasive, inexpensive, and convenient. However, osteoporosis fractures are clinically significant. BMD is a diagnostic and risk factor evaluation technique that helps doctors stratify fracture risk. DXA technology has had unexpected consequences (confusing patients and some healthcare professionals), thus BMD use for diagnosis versus risk assessment must be differentiated. Bone mineral density measurements of osteopenia or osteoporosis may not always predict fracture. Fragility fracture patients rarely have BMD T-scores below − 2.5. Most fracture patients have osteopenia, not BMD-defined osteoporosis60,61. Many non-skeletal factors affect fracture risk (see risk factors). DXA only measures BMD, therefore pathologic osteoporosis variables are excluded. Despite this limitation, DXA, vertebral or hip BMD T-scores can detect fragility fracture risk. Preventing bone fractures and their socioeconomic impact requires early osteoporosis diagnosis. Lifestyle adjustments and therapy may help osteopenic and osteoporotic patients prevent fractures. A position paper by leading practitioners advised secondary preventative assessment for all older fractures, including lifestyle, non-pharmacological, and pharmaceutical interventions to lower fracture risk. Due of DXA's limitations in assessing fragility fracture risk, the FRAX® calculator combines BMD with other, partly BMD-independent risk factors. Density testing assesses bone quantity, not quality. So, we need a low-cost tool to diagnose this condition early62,63. (Table 2).

Data

During the course of our studies, we noted a significant dearth of data that is openly available to the public and pertains to X-ray imaging of osteoporosis. The absence of sufficient data is a significant obstacle to the advancement of deep learning algorithms in addressing medical challenges, as previously noted. Upon conducting an extensive search, we have successfully identified a dataset comprising osteoporosis knee X-ray images. This dataset has been previously utilized in a published study64.

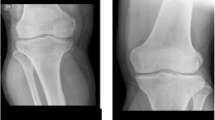

As it is clear from Table 3, the public dataset we accessed is not balanced. The class "osteopenic subjects" accounts for the vast majority of the data, whereas the other two classes barely make up a minute portion of the total. Therefore, it is to be expected that any classifier that is created around these data will contain some degree of bias. Figure 4 displays three examples of the dataset images.

Methods and experiments

In total, four tests were conducted utilizing four iterations of the Vision Transformer (ViT) algorithms. All of these models have been employed for the task of "feature extraction," wherein a pre-trained version of the method is utilized to extract a vector comprising certain picture features. This vector is subsequently employed for the purpose of classification. The problem that we tried to solve was a three-class classification problem. In Table 4, The Vision Transformer algorithms used in this study, and their features are shown. From this point forward, the results of our experiments will be presented. It is important to note that, in all instances, the parameters used to initialize functions and classes are the default settings as specified in the relevant software documentation, unless otherwise explicitly stated. The batch size used for experiments is 32. Each experiment has been conducted using epochs number of 10.

We have adopted the Adam optimizer implemented in Tensorflow with its default learning rate value 0.001 for all trainings. Also, categorical crossentropy loss function in Tensorflow have been used for the training phase of all experiments and its default parameters’ values are used. No data augmentation technique was applied on the data.

For each model the size of the feature vector it outputs and its number of parameters is mentioned in the Table 2. When analyzing the model designated as "vit_s16_fe," several noteworthy aspects may be inferred from the name that provide insights into the model. The term "s16" denotes the variable representing the "quantity of patches." To facilitate image analysis, every Vision Transformer (ViT) model partitions the images into distinct regions known as "patches". The numerical value "16" under the designation "s16" signifies that this particular model employs a division of its input images into 16 distinct patches. The model designated as "vit_b32_fe," which corresponds to model number 3, performs the same task as previously described, but with the inclusion of 32 patches. The letter "b" represents the term "base architecture". The abbreviation "fe" is used to refer to the term "feature extractor". The letter "r" in this context is the abbreviation for the term "residual," indicating the utilization of residual designs inside it. So, the models having “r” in their names, exploit residual blocks in their architectures which are a type of deep learning building blocks used usually in conjunction with CNN architectures65,66.

It is anticipated that a larger feature vector will provide a more comprehensive representation of the data instance, specifically in the context of images. Moreover, it is expected that a model with a greater number of parameters will possess an increased capacity to discern and comprehend the underlying patterns within the given data, provided that an ample amount of data is available for training the algorithm67.

We have used a pre-trained version of each of these models for feature extracting. This technique is called Transfer Learning (TL). TL is one of the most essential technologies in the era of artificial intelligence and deep learning. It aims to make the most of previously acquired expertise by applying it to other fields. Transfer learning, pre-training and fine-tuning, domain adaptation, domain generalization, and meta-learning are just a few of the subjects that have piqued the interest of the academic and application community throughout the years68. TL was created in response to the increased availability of ample labeled data. This approach leverages current data to address challenges associated with the collection of fresh annotated data. The objective of transfer learning is to enhance the performance of a target learner through the utilization of additional related source data69. In the case of this study, we the ViT models, have been trained on an image dataset called ImageNet.

ImageNet is a comprehensive dataset consisting of more than one million photos, categorized into 1000 distinct classes (https://www.image-net.org/download.php). It is commonly utilized as a standard for evaluating the efficacy of image classifying algorithms and also for pretraining and transfer the learned patterns to other classification problems70. One can read a full explanation of ImageNet in71.

Each one the models listed in Table 4 has been trained on a smaller version of the original ImageNet with the size of 1000. The models have been obtained from Tensorflow hub (https://tfhub.dev). TensorFlow Hub serves as a comprehensive collection of pre-trained machine learning models that are readily available for utilization and deployment. The experiments have been implemented using Python programming language version 3.10.12. In addition, the Tensorflow framework, specifically version 2.14.0, has been employed. Tensorflow, developed by Google, is a prevalent programming tool utilized for the implementation of deep learning algorithms. The dataset was partitioned into two distinct sets: a training set, 80 percent of the data, exclusively utilized during the training phase, and a held-out test set, which the algorithm was not exposed to during training and is employed for evaluating the dataset's performance. Additionally, it is worth noting that the optimization method Adam was utilized for the purpose of optimization, employing its default parameter settings.

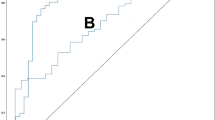

The findings presented in Table 5 indicate that an increase in the number of parameters is associated with a decline in performance. This observation suggests that the model may be overfitting due to a limited amount of available data1. Figure 5 is the visualized version of the Table 5.

To make sure that the obtained results are reliable, we repeated the experiments, this time using a standard cross validation with the number of folds 5. The results of the aforementioned experiment are presented in the Table 6. The mean accuracy improves by 0.2 points as the models get bigger, starting from the smallest ViT. Then, the performance drops significantly, considering the ViT_b32_fe. And the last one has performed better that the others, which indicates that there is a significant need for having a larger dataset of these types of images.

In Fig. 6, the Box and Whisker plots of the cross validation experiments on ViTs is manifested.

In Fig. 7, the confusion matrix for each model is shown. All models have made optimal efforts in accurately categorizing the class labeled as 1, which pertains to the category including "osteopenic subjects". The class with the highest number of examples in our dataset is observed to have a tendency for models to classify all instances as belonging to that particular category, as previously noted. The presence of bias in the models can be attributed to the uneven nature of the dataset. The performance of all models in classifying "osteoporotic subjects," which constitutes the smallest subset of cases in the dataset, has been the least successful.

In order to facilitate comparative analysis, we have also performed identical experiments with four commonly employed CNNs. In Table 7, the mentioned CNN algorithms along with their features are shown.

The VGG16 model is a convolutional neural network architecture that was introduced by K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman in their research article titled "Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition" at the University of Oxford. The VGG19 model is a modified version of the VGG model, characterized by its 19 levels. These layers consist of 16 convolutional layers, 3 fully connected layers, 5 max pooling layers, and 1 softmax layer. The model is comprised of a total of 143,667,240 parameters, often known as weights. This concept serves as the foundation for numerous scholarly investigations within this particular discipline72. ResNet50 is a modified version of the ResNet model, characterized by the inclusion of 48 Convolution layers. The ResNet model is extensively employed and serves as a fundamental framework for numerous scholarly investigations in this domain73. ResNetRS101 can be considered as a modified version of the ResNet architecture.

The experiment was conducted using pre-trained instances of each model from Tensorflow. Every model in the study has undergone pre-training using the ImageNet dataset. Furthermore, the Adam optimizer has been utilized for the purpose of optimization.

The outcome of the experiment conducted by CNN is presented in Table 8. An identical pattern is evident in the subsequent experiment as well: The efficacy degrades as the number of parameters increases due to the overfitting phenomenon.

The results in Table 8 are visualized in Fig. 8.

Just like the case with ViTs, we have conducted a separate experiment for CNNs, using cross validation technique with the number of folds 5. The result of that experiment is presented in Table 9. Cross validation results show that the accuracy improves with the increase in size of the models (with the exception of VGG19) (Fig. 9).

In Fig. 10, the Box and Whisker plots of the cross validation experiments of CNNs, is manifested.

The confusion matrices of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models are depicted in Fig. 9. Similar to the ViT experiment, the models exhibited optimal performance in the class characterized by the largest number of cases in the dataset, namely "osteopenic subjects," while demonstrating inferior performance in the class with the smallest number of instances, namely "osteoporotic subjects." Once again, the issue of imbalanced dataset has resulted in overfitting.

When the outcomes of two tests are compared, it is possible to draw the conclusion that ViT models have performed more successfully than CNNs, despite the fact that they suffer from drawbacks like as an insufficient amount of data and imbalanced data. The top performing CNN model, VGG16, is now being outperformed by the best performing ViT model, vit_s16. When there is access to a large quantity of data, it is natural to be able to do further and more comprehensive comparisons. In spite of this, it is clear from the parameters of this study that ViTs have a greater potential for diagnosis when compared to the traditional. Visual comparisons of the models belonging to the two families (ViTs and CNNs) are presented in Fig. 11. It is immediately apparent that the ViTs come out on top of the competition. In Fig. 11, ViT models and CNN models are compared in terms of their accuracies.

For the sake of ensuring the robustness of our comparison, we did a t-test between the results of models.

Table 10 clearly shows that, with the exception of row 3, the ViT consistently outperformed its CNN counterpart in all other comparisons.

We also went through the examination of the power of these two types of models, via another method. We utilised heatmap visualisations to evaluate their effectiveness in detecting illness locations in medical pictures. The main goal was to assess the precision and comprehensibility with which each model identifies problematic regions. The heatmaps obtained showed that the ViT s16 model outperformed the VGG16 model in reliably identifying the affected areas. The heatmaps generated by the ViT s16 model offer a higher level of accuracy and clarity in identifying specific regions of pathology. This highlights its potential as a more efficient tool for detecting diseases in medical imaging applications. The results indicate that the sophisticated structure of the ViT s16, which utilises self-attention processes, provides notable benefits in medical picture analysis compared to the conventional convolutional method of VGG16. Figures 12 and 13 manifest the result of the comparison for aforementioned two models.

Conclusion and discussion

In this study, we examined the ability of Vision Transformer models, a new technique in the field of deep-learning-based image analysis. We used these models to solve a difficult essential image classification problem, which is the diagnosis of osteoporotic individuals using X-ray pictures. Specifically, we addressed the considerable challenge to determine whether or not the subjects had osteoporosis, which is critical for proper clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Osteoporosis poses a substantial health concern due to its asymptomatic nature, frequently eluding detection until the manifestation of a fracture. This phenomenon exerts a significant impact on a vast number of individuals across the globe, with a notable predilection towards the female demographic aged 50 years and above. The pathological condition induces a state of diminished structural integrity and fragility within the skeletal system, thereby augmenting the susceptibility to fractures, primarily in the regions encompassing the hip, spine, and wrist. The occurrence of these fractures has the potential to result in the manifestation of persistent pain, long-term impairment, diminished self-sufficiency, and in extreme cases, mortality.

The substantial nature of the economic burden associated with osteoporosis is noteworthy. The estimated annual expenditure for the treatment of fractures associated with osteoporosis amounts to billions of dollars. Moreover, the affliction has the potential to induce a reduction in labor participation, a decline in overall efficiency, and a surge in medical expenditures. The implementation of preventive measures and the timely identification of osteoporosis are of utmost importance in effectively addressing this health concern. Modifications in one's lifestyle, encompassing the incorporation of consistent physical activity, adherence to a nutritious dietary regimen, and the abstention from both smoking and excessive alcohol intake, have been observed to exhibit potential in mitigating the onset of the aforementioned ailment. The utilization of bone density testing as a means of screening for osteoporosis can additionally facilitate the early identification of the ailment and enable timely intervention to mitigate the occurrence of fractures.

Vision Transformers may be the next important player in the field of medical image analysis using deep learning. The findings of this study demonstrated that they have triumphed over the traditional convolutional neural networks in the problem that we were attempting to tackle with this investigation. However, there are still a number of fundamental challenges that prevent the deep learning algorithm from being improved in this particular topic and, more generally speaking, in the field of medicine. The paucity of data that has been thoroughly cleaned and tagged appears to be the primary obstacle, which is a very significant issue that future studies will need to resolve. Our study revealed that there is a significant deficiency in the amount of publicly available X-ray data for osteoporosis patients. Expansion of our training set will support the development of more robust deep learning algorithms for X-rays in elderly patients.

Data availability

The dataset analysed during the current study are available in the Mendeley Data Knee Osteporosis repository, https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/fxjm8fb6mw/2.

References

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521(7553), 436–444 (2015).

Gatys, L. A., Ecker, A. S. & Bethge, M. (eds) Image style transfer using convolutional neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2016).

Johnson, J., Alahi, A. & Fei-Fei, L. (eds) Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 14 (Springer, 2016).

Mordvintsev, A., Olah, C. & Tyka, M. Inceptionism: Going deeper into neural networks (2015).

Potash, P., Romanov, A. & Rumshisky, A. (eds) Ghostwriter: Using an LSTM for automatic rap lyric generation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (2015).

Angelini, O., Moinet, A., Yanagisawa, K. & Drugman, T. Singing synthesis: With a little help from my attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.05881 (2019).

Champandard, A. J. Semantic style transfer and turning two-bit doodles into fine artworks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.01768 (2016).

Vinyals, O. & Le, Q. A neural conversational model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.05869 (2015).

Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O. & Le, Q. V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 27 (2014).

Li, J., Monroe, W., Shi, T., Jean, S., Ritter, A. & Jurafsky, D. Adversarial learning for neural dialogue generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.06547 (2017).

Hu, C. et al. Trustworthy multi-phase liver tumor segmentation via evidence-based uncertainty. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108289 (2024).

Wang, J., Zhu, H., Wang, S.-H. & Zhang, Y.-D. A review of deep learning on medical image analysis. Mob. Netw. Appl. 26, 351–380 (2021).

Zhou, L., Sun, X., Zhang, C., Cao, L. & Li, Y. LiDAR-based 3D glass detection and reconstruction in indoor environment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 3375965 (2024).

Miotto, R., Wang, F., Wang, S., Jiang, X. & Dudley, J. T. Deep learning for healthcare: Review, opportunities and challenges. Brief. Bioinform. 19(6), 1236–1246 (2017).

Chen, H., Engkvist, O., Wang, Y., Olivecrona, M. & Blaschke, T. The rise of deep learning in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 23(6), 1241–1250 (2018).

Gu, Y., Hu, Z., Zhao, Y., Liao, J. & Zhang, W. MFGTN: A multi-modal fast gated transformer for identifying single trawl marine fishing vessel. Ocean Eng. 303, 117711 (2024).

Ker, J., Rao, J. & Lim, T. Deep learning applications in medical image analysis. IEEE Access 6, 9375–9389. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2788044 (2018).

Qi, F. et al. Glass makes blurs: Learning the visual blurriness for glass surface detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 20(4), 6631–6641 (2024).

Puttagunta, M. & Ravi, S. Medical image analysis based on deep learning approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80, 24365–24398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-10707-4 (2021).

Kebaili, A., Lapuyade-Lahorgue, J. & Ruan, S. Deep learning approaches for data augmentation in medical imaging: A review. J. Imaging. 9(4), 81 (2023).

Altaf, F., Islam, S. M., Akhtar, N. & Janjua, N. K. Going deep in medical image analysis: Concepts, methods, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 7, 99540–99572 (2019).

Dhar, T., Dey, N., Borra, S. & Sherratt, R. S. Challenges of deep learning in medical image analysis—Improving explainability and trust. IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc. 4(1), 68–75 (2023).

Saraf, V. et al. (eds) Deep Learning Challenges in Medical Imaging (Springer, 2020).

O'Shea, K. & Nash, R. An introduction to convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.08458 (2015).

Wang, Z. J. et al. CNN explainer: Learning convolutional neural networks with interactive visualization. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 27(2), 1396–1406 (2020).

Islam, K. Recent advances in vision transformer: A survey and outlook of recent work. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.01536 (2022).

Deininger, L., Stimpel, B., Yuce, A., Abbasi-Sureshjani, S., Schönenberger, S., Ocampo, P. et al. A comparative study between vision transformers and CNNs in digital pathology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.00389 (2022).

Raghu, M., Unterthiner, T., Kornblith, S., Zhang, C. & Dosovitskiy, A. Do vision transformers see like convolutional neural networks?. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 12116–12128 (2021).

Khan, A., Rauf, Z., Sohail, A., Rehman, A., Asif, H., Asif, A. et al. A survey of the vision transformers and its CNN-transformer based variants. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.09880 (2023).

La Manna, F. et al. Molecular profiling of osteoprogenitor cells reveals FOS as a master regulator of bone non-union. Gene 874, 147481 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. lncRNA Xist regulates osteoblast differentiation by sponging miR-19a-3p in aging-induced osteoporosis. Aging Dis. 11(5), 1058–1068 (2020).

Johnston, C. B. & Dagar, M. Osteoporosis in older adults. Med. Clin. North Am. 104(5), 873–884 (2020).

Šromová, V., Sobola, D. & Kaspar, P. A brief review of bone cell function and importance. Cells 12(21), 2576 (2023).

Gao, Y., Patil, S. & Jia, J. The development of molecular biology of osteoporosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(15), 8182 (2021).

Gerosa, L. & Lombardi, G. Bone-to-brain: A round trip in the adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Front. Physiol. 12, 623893 (2021).

Guajardo-Correa, E. et al. Estrogen signaling as a bridge between the nucleus and mitochondria in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 968373 (2022).

Sauerschnig, M. et al. Effect of COX-2 inhibition on tendon-to-bone healing and PGE2 concentration after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Eur. J. Med. Res. 23(1), 1 (2018).

Halloran, D., Durbano, H. W. & Nohe, A. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 in development and bone homeostasis. J. Dev. Biol. 8(3), 19 (2020).

Razavi, Z.-S. et al. Advancements in tissue engineering for cardiovascular health: A biomedical engineering perspective. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1385124 (2024).

Hatami, S., Tahmasebi Ghorabi, S., Mansouri, K., Razavi, Z. & Karimi, R. A. The role of human platelet-rich plasma in burn injury patients: A single center study. Canon J. Med. 4(2), 41–45 (2023).

Xu, J., Yu, L., Liu, F., Wan, L. & Deng, Z. The effect of cytokines on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone remodeling in osteoporosis: A review. Front. Immunol. 14, 1222129 (2023).

Jiang, Z., Han, X., Zhao, C., Wang, S. & Tang, X. Recent advance in biological responsive nanomaterials for biosensing and molecular imaging application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(3), 1923 (2022).

Razavi, Z., Soltani, M., Pazoki-Toroudi, H. & Chen, P. CRISPR-microfluidics nexus: Advancing biomedical applications for understanding and detection. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 376, 115625 (2024).

Diegel, C. R. et al. Inhibiting WNT secretion reduces high bone mass caused by Sost loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations in Lrp5. Bone Res. 11(1), 47 (2023).

Molaei, A. et al. Pharmacological and medical effect of modified skin grafting method in patients with chronic and severe neck burns. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 5, 369–375 (2022).

Marcadet, L., Bouredji, Z., Argaw, A. & Frenette, J. The roles of RANK/RANKL/OPG in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscles in health and disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 903657 (2022).

Mahmoudvand, G., Karimi Rouzbahani, A., Razavi, Z. S., Mahjoor, M. & Afkhami, H. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for non-healing diabetic foot ulcer infection: New insight. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1158484 (2023).

Wang, R. N. et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis. 1(1), 87–105 (2014).

Otaghvar, H. et al. A brief report on the effect of COVID 19 pandemic on patients undergoing skin graft surgery in a burns hospital from March 2019 to March 2020. J. Case Rep. Med. Hist. https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2200138 (2022).

Wein, M. N. & Kronenberg, H. M. Regulation of bone remodeling by parathyroid hormone. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8(8), a031237 (2018).

Taheripak, G. et al. SIRT1 activation attenuates palmitate induced apoptosis in C2C12 muscle cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 51(1), 354 (2024).

Hatami, S., Tahmasebi Ghorabi, S., Ahmadi, P., Razavi, Z. & Karimi, R. A. Evaluation the effect of Lipofilling in Burn Scar: A cross-sectional study. Canon J. Med. 4(3), 78–82 (2023).

LeBoff, M. S. et al. The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 33(10), 2049–2102 (2022).

Høiberg, M. P., Rubin, K. H., Hermann, A. P., Brixen, K. & Abrahamsen, B. Diagnostic devices for osteoporosis in the general population: A systematic review. Bone 92, 58–69 (2016).

Yu, Y. et al. Targeting loop3 of sclerostin preserves its cardiovascular protective action and promotes bone formation. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 4241 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between serum soluble α-klotho and bone mineral density (BMD) in middle-aged and older adults in the United States: A population-based cross-sectional study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 35(10), 2039–2049 (2023).

Han, X. et al. Multifunctional TiO2/C nanosheets derived from 3D metal–organic frameworks for mild-temperature-photothermal-sonodynamic-chemodynamic therapy under photoacoustic image guidance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 621, 360–373 (2022).

Song, Z. H. et al. Effects of PEMFs on Osx, Ocn, TRAP, and CTSK gene expression in postmenopausal osteoporosis model mice. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 11(3), 1784–1790 (2018).

Yeap, S. S. et al. Different reference ranges affect the prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia in an urban adult Malaysian population. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 6(4), 168–172 (2020).

Yu, W. et al. Comparison of differences in bone mineral density measurement with 3 hologic dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan modes. J. Clin. Densitom. 24(4), 645–650 (2021).

Gai, Y. et al. Rational design of bioactive materials for bone hemostasis and defect repair. Cyborg Bionic Syst. (Washington, DC). 4, 0058 (2023).

Al-Hashimi, L., Klotsche, J., Ohrndorf, S., Gaber, T. & Hoff, P. Trabecular bone score significantly influences treatment decisions in secondary osteoporosis. J. Clin. Med. 12(12), 4147 (2023).

Bahadori, S., Williams, J. M., Collard, S. & Swain, I. Can a purposeful walk intervention with a distance goal using an activity monitor improve individuals’ daily activity and function post total hip replacement surgery. A randomized pilot trial. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 4, 0069 (2023).

Wani, I. M. & Arora, S. Osteoporosis diagnosis in knee X-rays by transfer learning based on convolution neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82(9), 14193–14217 (2023).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. (eds) Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2016).

Veit, A., Wilber, M. J. & Belongie, S. Residual networks behave like ensembles of relatively shallow networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 29 (2016).

Sarker, I. H. Deep learning: A comprehensive overview on techniques, taxonomy, applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2(6), 420 (2021).

Wang, J. & Chen, Y. Introduction to Transfer Learning: Algorithms and Practice (Springer Nature, 2023).

Farahani, A., Pourshojae, B., Rasheed, K. & Arabnia, H. R. (eds) A concise review of transfer learning. 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI) (IEEE, 2020).

Recht, B. et al. (eds) Do Imagenet Classifiers Generalize to Imagenet. International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2019).

Deng, J. et al. (eds) Imagenet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (IEEE, 2009).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Koonce, B. & Koonce, B. ResNet 50. Convolutional Neural Networks with Swift for Tensorflow: Image Recognition and Dataset Categorization 63–72 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S (Ali Sarmadi): Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Writing-original draft; Z.S.R (Zahra Sadat Razavi): Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Writing-original draft; A.V.W (Andre J. van Wijnen): Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; M.S (Madjid Soltani): Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarmadi, A., Razavi, Z.S., van Wijnen, A.J. et al. Comparative analysis of vision transformers and convolutional neural networks in osteoporosis detection from X-ray images. Sci Rep 14, 18007 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69119-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69119-7

This article is cited by

-

Prediction of lymph node metastasis and recurrence risk in early-stage oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma with fully automated MRI deep learning

Cancer Imaging (2026)

-

Advancing Congenital Heart Defect Treatments: Synergistic Approaches with Stem Cells and Functional Scaffolds

Stem Cell Reviews and Reports (2026)

-

Bone Osteoporosis Fractures Detection with Deep Learning: An X-ray Image Analysis Approach

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2026)

-

Precision Nanotechnology: Revolutionizing Therapeutic Strategies Against Drug-Resistant Breast Cancer

Annals of Biomedical Engineering (2026)

-

Enhanced diagnosis of osteoporosis using vision transformer with lumbar MRI

BMC Medical Imaging (2025)