Abstract

Observational studies suggest dyslipidemia as an atopic dermatitis (AD) risk factor and posit that lipid-lowering drugs may influence AD risk, but the causal link remains elusive. Mendelian randomization was applied to elucidate the causal role of serum lipids in AD and assess the therapeutic potential of lipid-lowering drug targets. Genetic variants related to serum lipid traits and lipid-lowering drug targets were sourced from the Global Lipid Genetics Consortium GWAS data. Comprehensive AD data were collated from the UK Biobank, FinnGen, and Biobank Japan. Colocalization, Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR), and mediation analyses were utilized to validate the results and pinpoint potential mediators. Among assessed targets, only Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) was significantly linked to a reduced AD risk, corroborated across three separate AD cohorts. No association between serum lipid concentrations or other lipid-lowering drug targets and diminished AD risk was observed. Mediation analysis revealed that beta nerve growth factor (b-NGF) might mediate approximately 12.8% of PCSK9's influence on AD susceptibility. Our findings refute dyslipidemia's role in AD pathogenesis. Among explored lipid-lowering drug targets, PCSK9 stands out as a promising therapeutic agent for AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AD is a chronic and recurrent inflammatory skin disease characterized by a solid genetic predisposition1. The pathogenesis of AD is closely intertwined with lipid metabolism disorders and metabolic syndrome. Several observational studies have proposed a significant association between circulating blood lipid levels, such as total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and AD2,3,4. However, it is essential to note that cross-sectional observational epidemiological studies have inherent methodological limitations and are susceptible to confounding factors. Consequently, the causal relationship between serum lipids and AD remains elusive.

Lipid-lowering drugs have a crucial role in the management of metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, several studies have reported the potential effectiveness of statins in treating various dermatological conditions, including psoriasis, AD, alopecia areata, and vitiligo5,6,7. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties of statins provide a rationale for their potential therapeutic use in diseases where inflammation and immune responses play critical roles in the pathogenesis8,9,10. However, it is essential to acknowledge that current studies investigating the use of lipid-lowering drugs in the treatment of AD are primarily observational. These observational studies are susceptible to limitations such as reverse causation (i.e., AD causing dyslipidemia) and confounding factors (i.e., unmeasured variables that may influence the effect of lipid-lowering drugs and the risk of AD). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard for determining the efficacy of drugs. However, ethical and practical challenges often limit the feasibility of conducting large-scale RCTs in this context. Consequently, in the absence of robust evidence from large RCTs, it remains unclear whether lipid-lowering drugs would be genuinely effective in treating AD.

With the increasing popularity of GWAS, Mendelian randomization (MR) has emerged as a potentially effective method to address the aforementioned challenges11. MR utilizes genetic variants (alleles) as instrumental variables, mimicking RCTs’ design, where individuals are randomly assigned to different groups based on their alleles. This enables MR to examine whether individuals with specific risk factor alleles have a higher or lower risk of developing a particular disease than those without such alleles12. Moreover, MR can infer causal relationships between drug targets (in "drug target MR") or risk factors (in "biomarker MR") and their associated outcomes13. In the context of "drug target MR," genetic variation in the gene encoding the target protein can modulate the gene's expression or function, resembling the drug's mechanism of action. Consequently, MR analysis can provide insights into the potential outcomes of RCTs14,15. MR analysis has now been widely adopted to anticipate the potential impacts of drug targets on neurological diseases, dermatological conditions, and cardiovascular diseases16,17,18.

Hence, we conducted MR analysis to assess the impact of serum lipid and lipid-lowering drug targets on AD and to investigate the possible mechanism of how lipid-lowering drug targets influence AD.

Materials and methods

The current investigation followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Mendelian Randomisation (STROBE-MR) guidelines (eTable 1 in supplement 1)19. All utilized GWAS and protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) data were sourced from public databases that have received appropriate ethical clearance. Specifically, data from the UK Biobank (UKB) secured ethical consent from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, with all involved participants granting informed consent. Comprehensive details about the datasets are provided in eTable 2 (supplement 1). Figure 1 illustrates the study's analytical flow.

Detailed flow chart of the study. Assumption 1: genetic variation should be strongly associated with the exposure of interest; Assumption 2: the genetic variants used as instruments should be independent of confounding factors that may influence the relationship between the exposure and the outcome; Assumption 3: the genetic variants should only affect the outcome through their impact on the exposure of interest. Abbreviations: PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; GWAS, genome-wide association study; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1; GLGC, Global Lipids Genetics Consortium; TC, total cholesterol; APOB, Apolipoprotein B-100; TG, triglyceride; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BBJ, Biobank of Japan; AD, atopic dermatitis; HMGCR, HMG-CoA reductase; ANGPTL3, angiopoietin-like 3; PPARA, Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Alpha; LDLR, LDL Receptor; APOC3, Apolipoprotein C-III. pQTL: Protein quantitative trait loci.

Genetic Association for AD

For the detection of genetic variants related to AD, a GWAS was performed using data from the UKB, encompassing 7,433 AD cases and 256,177 controls. The genotyping and quality control protocols for the UKB have been delineated elsewhere20. Detailed information regarding the current GWAS can be found in the eMethods section of Supplement 1. AD diagnosis was based on the International Classification of Diseases Coding System (ICD-10: L20) combined with Read-linked primary care data. To enhance diagnostic precision, cases flagged with psoriasis (ICD-10: L40) were disregarded. Genetic association magnitudes were ascertained through linkage disequilibrium score regression, revealing high congruence (rg = 0.982; P = 7.65 × 10−8) with a preceding GWAS by Paternoster et al. focused solely on physician-confirmed AD diagnoses21. In total, 19 SNPs exhibited significant associations with AD (p-value < 5 × 10–8) within the UKB GWAS.

To corroborate our findings and widen applicability to East Asian cohorts, GWAS data for AD was fetched from both the FinnGen database and the Biobank Japan (BBJ). The FinnGen set (release 9) contained 13,473 AD cases and 336,589 controls, while the BBJ dataset featured 4,296 AD patients alongside 163,807 controls. Case demarcations for both datasets drew from the ICD-10 code L20. To gauge genetic alignment with the results from Paternoster et al., genetic correlation coefficients were computed, resulting in rg = 0.974 (P = 6.56 × 10−18) for FinnGen and rg = 0.845 (P = 7.02 × 10−5) for BBJ. For the initial analysis phase, we prioritized the genetic association data from the UKB, attributing higher confidence to its case definitions relative to the FinnGen and BBJ, both of which employed automated case identification. The study of Budu-Aggrey et al. 22, which included 40 AD cohorts comprising 60,653 cases and 804,329 controls of European ancestry, served as a validation dataset. Due to sample overlap, this dataset was not utilized in the primary analysis. Its main application was to confirm the associations between lipid levels and AD. Lastly, a meta-analysis consolidating MR outcomes from both UKB and FinnGen was conducted using the R software's meta package (version 6.1-0)23.

Genetic Proxies for Serum Lipid and Lipid-Lowering Drugs

We sourced genetic association outcomes for LDL, TG, and TC (P < 5 × 10–8, R2 < 0.001, clumping window size = 10,000 kb) from the comprehensive meta-analysis of GWAS spearheaded by the GLGC24. This inclusive meta-analysis encompassed approximately 1.32 million individuals of European descent and a subset of 146,500 individuals of East Asian descent. To counteract potential biases arising from sample overlaps, we incorporated GWAS data from GLGC participants, deliberately excluding those from FinnGen (n = 1,177,987) or UKB (n = 842,660) when scrutinizing results from the FinnGen or UKB GWAS correspondingly. Within the GLGC dataset, we exclusively incorporated lipid data from individuals with East Asian ancestry, aiming to curb biases induced by population variations when juxtaposing the outcome with the BBJ GWAS.

When pinpointing lipid-lowering medications and emerging therapeutic agents, such as alirocumab (PCSK9 inhibitors), statins (HMGCR inhibitors), and fenofibrate (PPARA inhibitors), we consulted the most recent dyslipidemia management guidelines and pertinent literature reviews25,26,27,28 (eTable 3 in supplement 1). Our approach in selecting genetic variants mirrored methodologies implemented in earlier research endeavors16,29. In essence, we opted for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) situated within the pertinent genes (± 100 kb of the gene locale with a linkage disequilibrium threshold of r2 < 0.3)30. Additionally, the association magnitude between SNP and lipid required to exceed the locus-wide significance benchmark (P < 5 × 10–8).

For the authentication of drug targets earmarked as salient in the MR examination, we accessed the public pQTL dataset from a plasma proteomic investigation helmed by deCODE, comprising 35,559 European participants31. The term pQTL alludes to genetic variants that correlate with protein expression magnitudes. In terms of SNP selection criteria, we adopted a P-value benchmark of less than 5 × 10–8 and clumped LD r2 threshold of 0.001.

Statistical analysis

Utilizing the inverse variance-weighted (IVW) approach (both fixed and random effects), we determined the overall causal relationship between genetically-inferred circulating lipid attributes and lipid-lowering therapies on AD. All findings were standardized based on the impact of individual SNPs on lipid concentrations, denoting alterations in units of 1 mmol/L (e.g., TC at 41.8 mg/dL; TG at 88.9 mg/dL; LDL-C at 38.7 mg/dL).

A valid instrumental variable is predicated on three foundational assumptions, as depicted in Fig. 132 and emethods in supplement 1. Additionally, we corroborated our primary findings through the use of colocalization analysis and Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) analysis. The details of colocalization and SMR analysis are presented in eMethods section of Supplement 1.

We orchestrated a two-step mediation MR analysis to discern if genetically inferred lipid-lowering medications influenced AD via circulating cytokines and growth factors33,34,35, employing eQTL data procured from a GWAS study encompassing 8,293 Finnish participants36. An exhaustive design of this mediation MR analysis is visualized in Fig. 1. The “Product of coefficients” strategy33 was adopted to gauge the indirect effects of genetically inferred lipid-lowering therapies on AD susceptibility via each potential mediator. Indirect effects' standard errors were computed via the delta method37.

Significant outliers were identified and rectified using MR-Egger regression alongside the Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO)38 tests. The global test scrutinized the prevalence of horizontal pleiotropy across all instruments38. Furthermore, heterogeneity across all SNPs was evaluated using Cochran’s Q-test statistics. Sensitivity analysis adjusted for the LD structure due to a less robust LD (r2 < 0.3) chosen for drug target proxies. For prominent drug target MR associations, more stringent LD thresholds (r2 < 0.1, r2 < 0.01, and r2 < 0.001, respectively) were employed to verify our findings' robustness.

Multiple test corrections for P-values were executed through the Bonferroni method. For instance, P-values below 0.016 (0.05/3), 0.005 (0.05/9), and 0.001 (0.05/41) were deemed significant for the three lipid traits, nine lipid-lowering drug traits, or 41 circulating cytokines and growth factors, respectively. P-values less than 0.05 were treated as statistically significant for all other standalone analyses. All computational tasks in this research were executed using R software (version 4.2.2), python (version 3.9.15), and Linux (CentOS) system. Employed packages incorporated ‘TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.6)’, ‘PLINK (version 2.0)’, ‘smr (version 1.3.1)’, ‘LDSC’, ‘meta (version 6.1-0)’, ‘coloc (version 5.1.0.1)’, ‘phenoscanner (version 1.2.2)’, ‘MRPRESSO (version 1.0)’, ‘Rmediation (version 1.0)’, and ‘CMplot (version 4.3.1)’.

Ethics approval

All the genome-wide association study (GWAS) and protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) data used in this research were sourced from public databases that have secured the necessary ethical approvals. Specifically, data from the UK Biobank (UKB) study, which was a significant contributor to our dataset, had been ethically sanctioned by the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee. It's paramount to highlight that all participants in the UKB study had given informed consent prior to their inclusion. This ensures that our research is rooted in data that is both ethically obtained and respects the rights and wishes of all contributing individuals.

Results

Circulating lipid traits and risk of AD

In the UKB training dataset, after excluding SNPs significantly associated with confounders (sTable 1 in supplement 2), we identified a total of 263 independent SNPs significantly associated with LDL, 292 SNPs significantly associated with TC, and 289 SNPs significantly associated with TG as instrumental variables for lipids (sTable 2 in supplement 2). MR results suggest that none of the three genetically proxied lipid reductions are associated with AD in the UKB training, FinnGen validation, BBJ development, and Budu-Aggrey A et al. validation cohorts (Table 1 and eFig. 2). The results of the reverse Mendelian Randomization (MR) analysis, using the cohort data from Budu-Aggrey A et al. as the exposure, suggest that AD does not have a reverse causal relationship with serum lipids such as LDL cholesterol, TG, and TC (eFig. 3 in Supplement 1).

Lipid-lowering drug targets and risk of AD

In the training cohort, after excluding some variants selected to instrument HMGCR and APOC3 that were associated with confounders (sTable 1 in supplement 2), we identified 42, 26, 10, 49, and 32 SNPs that represent LDL reduction by inhibiting PCSK9, HMGCR, NPC1L1, LDLR, and APOB, respectively (sTable 2 in supplement 2). In addition, we identified 20, 53, 5, and 36 SNPs that represent the reduction of TC by inhibiting ANGPTL3, LPL, PPARA, and APOC3, respectively (sTable 1 in supplement 2). In the training and validation cohort, besides ANGPTL3 (P = 0.013), the other eight genetically proxied drug targets showed significant associations (P < 0.005) with lower CAD risk in the positive control analysis (eFig. 4 in supplement 1), confirming the validity of genetic instrumentation, which agreed with previous studies39. The F values of all instruments in the analysis are greater than 10, excluding the possibility of weak instruments (sTable 1 in supplement 2).

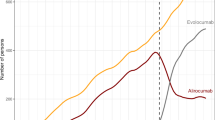

MR estimates from the UK Biobank (UKB) training cohort {OR and 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.68 (0.53–0.88), p-value = 0.0030} and the FinnGen validation cohort {OR and 95% CI = 0.88 (0.83–0.94), p-value = 0.0001} both indicated that genetically proxied inhibition of PCSK9, equivalent to a 1-mmol/L (38.7 mg/dL) reduction in LDL cholesterol, was associated with a respective 32% and 12% reduction in the risk of AD (Fig. 2). Additionally, there was no significant statistical heterogeneity between the two estimates (P = 0.06).The BBJ development cohort {OR and 95% CI = 0.72 (0.53–0.98); p-value = 0.0395 > 0.05/7} showed similar results, but did not reach statistical significance (eFig. 5 in supplement 1). Although genetically proxied inhibition of ANGPTL3 was found to be associated with an increased risk of AD in the UKB training cohort (Fig. 2), the protective effect of ANGPTL3 inhibition on CAD was not statistically significant (P = 0.013, eFig. 4 in supplement 1). No causal relationship was observed between other drug targets (HMGCR, LDLR, NPC1L1, APOB, APOC3, LPL, and PPARA) and AD.

Association of genetically-proxied drug targets with risk of AD in UKB and FinnGen cohorts. FINN, FinnGen; AD, atopic dermatitis; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphisms; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein; TC, Total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; LDLR, LDL Receptor; HMGCR, HMG-CoA reductase; ANGPTL3, angiopoietin-like 3; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1; APOC3, Apolipoprotein C-III; PPARA, Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Alpha; APOB, Apolipoprotein B-100; LPL, lipoprotein lipase.

Alternative MR methods yielded similar results (eTable 4 in supplement 1). Etable 5 (supplement 1) displays the statistical power of MR analysis and the intensity of genetic instruments for each drug target. Based on Cochran’s IVW Q test, these IVs showed no significant heterogeneity in the primary analysis (eTable 6 in supplement 1). No signs of pleiotropy were detected for MR-Egger intercepts and MR-PRESSO in the primary analysis, strengthening causal inference (eTable 7 and eTable 8 in supplement 1). Using UKB data, the posterior probability of LDL and AD colocalization in the PCSK9 gene region is 94.6% (eTable 9 in supplement 1). Further analyses of LD thresholds with stricter thresholds in training and validation cohorts did not significantly alter the confidence interval width (eTabless 10 and 11 in supplement 1).

Protein expression and the risk of AD

Genetically proxied circulating PCSK9 levels were significantly associated with reduced risk of AD in the UKB training cohort {OR and 95% CI = 0.89 (0.81–0.98); p-value = 0.0147} and FinnGen validation cohort {OR and 95% CI = 0.93 (0.89–0.98); p-value = 0.0072, Fig. 3}. In addition, since the previous analysis suggested that ANGPTL3 was not significant in the positive control analysis, we investigated whether changes in circulating ANGPTL3 expression were associated with the risk of AD. The results suggest that there is no statistical significance in the UKB training cohort (Fig. 3). The reverse MR analysis conducted on UKB and FinnGen cohorts indicates that there is no reverse causal relationship between AD and the plasma protein expression levels of PCSK9 (eFig. 3 in Supplement 1). Additionally, the results from the colocalization analysis suggest that the PP.H4 between PCSK9 and AD is 0.605 (eTable 9 in supplement 1). Although this value falls below the commonly referenced threshold of 0.8, it still points to a significant association between these traits. In contrast, ANGPTL3's association with AD demonstrates a PP.H4 of 0.018 and a PP.H1 of 0.936. This indicates that while there is a genetic association within the region specific to ANGPTL3, it likely operates independently of AD, suggesting that the ANGPTL3 pQTL does not share a causal variant with AD. The results from the SMR analysis suggest that inhibiting PCSK9 protein expression in the blood may reduce the risk of AD (eTable 12 in supplement 1).

Mediation Mendelian randomisation analysis

Since the initial results suggest that there is no significant causal relationship between the genetically proxied LDL reduction and AD, the genetically proxied PCSK9 inhibition does not affect AD by reducing LDL. We applied two-step mediation MR analysis to explore whether the genetically proxied PCSK9 inhibition affects AD through circulating cytokines and growth factors. In the first step, genetic instrumentation mimicking PCSK9 inhibitors was used to estimate the causal effects of exposure on the underlying mediators. Out of 41 potential mediators, we identified only significant causal relationships between mimic PCSK9 inhibitors and b-NGF, IL-1B, MIF, and SCGFb (eTable 13 in supplement 1). Moreover, inhibition of PCSK9 was associated with a decrease in b-NGF and IL-1B and an increase in MIF and SCGFb (eTable 13 in supplement 1). In the second step, we assessed the causal effect of mediators on AD risk using genetic instrumentation for the four cytokines described above. The results suggest that only b-NGF and AD have a significant causal relationship and the risk of AD increases by 22.5% for every 1SD increase in b-NGF. (eTable 14 in supplement 1). In the two-step, MR analysis, the exposed and mediated instrumental variables did not overlap and were independently related SNPs. Multivariate MR analysis, adjusting for b-NGF, demonstrated that the direct effect of mimetic PCSK9 inhibitors on AD (β) was lower compared to the univariate IVW estimates (multivariate IVW β = -0.331; OR = 0.718; 95% CI 0.552 to 0.934; P = 0.003), which suggest that the reduction of AD risk by mimetic PCSK9 inhibitors is mediated in part by the reduction of b-NGF expression. The indirect effect of mimic PCSK9 inhibitors on AD via b-NGF was 0.953 (95% CI 0.888 to 0.998; p = 0.033), with a mediated proportion of 12.8% (Fig. 4). No evidence of heterogeneity and pleiotropy was found in the primary analysis (eTables 15 and 16 in supplement 1).

Mediation analysis of PCSK9’s effect on atopic dermatitis through beta nerve growth factor using two-step Mendelian randomisation. ‘Direct effect’ means PCSK9’s effect on AD risk with mediator adjustment. ‘Indirect effect’ means PCSK9’s effect on AD risk via the mediator. GWAS, Genome-wide association study; PCSK9, Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; GLGC, Global Lipids Genetics Consortium; β-NGF, Beta nerve growth factor.

Discussion

In this extensive study involving 25,202 individuals with AD and 756,573 controls, our findings indicate that genetically proxied inhibition of PCSK9 significantly reducing the risk of developing AD. The expression level of PCSK9 protein in blood has a significant causal relationship with AD.Conversely, we found no substantial evidence supporting the involvement of the other eight lipid-lowering drug targets and serum lipid traits in reducing the risk of AD. This suggests that the impact of PCSK9 on AD risk operates independently of its lipid-lowering effects. Additionally, our mediation analysis indicates that the reduction in AD risk associated with PCSK9 may be partially attributed to its influence on lowering b-NGF expression levels.

PCSK9, a member of the proprotein convertase family, plays a significant role in elevating plasma LDL levels by facilitating the degradation of LDL receptors40. Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that PCSK9 is involved in inflammatory pathways41,42. In a rat model of alcoholic liver disease, inhibiting PCSK9 has been shown to reduce the levels of circulating inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (such as IL-22, TNFa, IL-33, IL-1β, IL-2, and IL-17α) and local neutrophil infiltration43. In vitro studies using human recombinant PCSK9 have demonstrated that it activates macrophages, leading to increased expression of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6. Conversely, inhibition of PCSK9 has been shown to mitigate inflammation in stimulated macrophages by blocking nuclear factor-κB44. The upregulation of inflammatory factors like IL-17α, IL-33, and NF-κB, as well as the accumulation of neutrophils and macrophages, contribute to the exacerbation of epidermal inflammation, impairment of the skin barrier, and the initiation and progression of AD.45,46,47.

b-NGF is an essential substance in the skin that regulates the maintenance and repair of nerves. Circulating b-NGF expression levels in AD patients were significantly higher than in control groups. And there was a strong correlation between plasma b-NGF and symptom severity48,49. In NC/Nga mice, an animal model of AD, repeated application of b-NGF inhibitors reduced skin damage, scratching behavior, and epidermal innervation, improving the AD phenotype50. Currently, no basic research has explored the relationship between PCSK9 and b-NGF, and no basic or clinical research has explored whether inhibition of PCSK9 is effective in treating AD. Our research suggests that inhibition of PCSK9 reduces the risk of AD, which is likely to be partly mediated by b-NGF.

One of the main strengths of this study is the simultaneous use of datasets from both European and East Asian populations, ensuring the reproducibility and generalizability of the results to different populations. Cohort studies examining the association between lipid-lowering drugs and AD risk and prognosis may be limited by indication bias and reverse causation. In contrast, MR can estimate causal associations between exposure and outcome with less bias from unmeasured confounders when instrumental variable assumptions are met.

However, this MR study has several limitations. Firstly, genetic variants may reflect the lifelong impact of lipid changes on AD risk, which may differ from the short-term effects of lipid-lowering drugs. Additionally, genetic variants in systemic PCSK9 may not perfectly represent the intervention of the target tissue51. Secondly, as with all MR studies, it is not possible to empirically test the instrumental variable assumption. While sensitivity analyses exploring potential sources of deviation provide reassurance, there is a possibility of pleiotropy or confounding factors influencing the estimates. Lastly, it is essential to note that the study only predicts on-target effects for specific drug targets and does not account for potential off-target effects.

In summary, this study does not support a causal link between lipid traits (TC, LDL-C, and TG) and AD. Moreover, PCSK9 inhibition, a promising drug target for AD, is causally associated with a lower risk of AD, possibly partly by regulating b-NGF. The underlying mechanisms should be clarified in further studies.

Data availability

The research presented in this article employed the UKB Resource under Application Number 93810, encompassing an extended scope. The UKB operates as an open-access platform. Interested researchers aiming to utilize the UKB dataset can initiate the process by registering and submitting their application through the UK Biobank's official portal at http://ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/. For any additional information or queries pertaining to our data sources or research methodology, the corresponding author stands ready to assist and can be reached upon request.

Abbreviations

- MR:

-

Mendelian randomization

- APOC3:

-

Apolipoprotein C-III

- SNP:

-

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- LDLR:

-

LDL Receptor

- HMGCR:

-

HMG-CoA reductase

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- PPARA:

-

Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Alpha

- ANGPTL3:

-

Angiopoietin-like 3

- IVW:

-

Inverse variance weighted

- NPC1L1:

-

Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- PCSK9:

-

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- MR-PRESSO:

-

MR Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier

- APOB:

-

Apolipoprotein B-100

- LPL:

-

Lipoprotein lipase

References

Tanaka, N. et al. Eight novel susceptibility loci and putative causal variants in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.04.019 (2021).

Shalom, G. et al. Atopic dermatitis and the metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional study of 116 816 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 33, 1762–1767 (2019).

Huang, A. H. et al. Real-world comorbidities of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric ambulatory population in the United States. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 85, 893–900 (2021).

Kimata, H. Fatty liver in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 56, 460 (2001).

Egesi, A., Sun, G., Khachemoune, A. & Rashid, R. M. Statins in skin: research and rediscovery, from psoriasis to sclerosis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 9, 921–927 (2010).

Jowkar, F. & Namazi, M. R. Statins in dermatology. Int. J. Dermatol. 49, 1235–1243 (2010).

Luan, C. et al. Potentiation of Psoriasis-Like Inflammation by PCSK9. J. Invest. Dermatol. 139, 859–867 (2019).

Gurevich, V. S., Shovman, O., Slutzky, L., Meroni, P. L. & Shoenfeld, Y. Statins and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 4, 123–129 (2005).

Qi, X.-F. et al. Fluvastatin inhibits expression of the chemokine MDC/CCL22 induced by interferon-gamma in HaCaT cells, a human keratinocyte cell line. Br. J. Pharmacol. 157, 1441–1450 (2009).

Namazi, M. R. Statins: Novel additions to the dermatologic arsenal?. Exp. Dermatol. 13, 337–339 (2004).

Walker, V. M., Davey Smith, G., Davies, N. M. & Martin, R. M. Mendelian randomization: A novel approach for the prediction of adverse drug events and drug repurposing opportunities. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 2078–2089 (2017).

Arsenault, B. J. From the garden to the clinic: How Mendelian randomization is shaping up atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention strategies. Eur. Heart J. 43, 4447–4449 (2022).

Schmidt, A. F. et al. Genetic drug target validation using Mendelian randomisation. Nat. Commun. 11, 3255 (2020).

Gill, D. et al. Use of genetic variants related to antihypertensive drugs to inform on efficacy and side effects. Circulation 140, 270–279 (2019).

Reay, W. R. & Cairns, M. J. Advancing the use of genome-wide association studies for drug repurposing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 658–671 (2021).

Zhao, S. S., Yiu, Z. Z. N., Barton, A. & Bowes, J. Association of lipid-lowering drugs with risk of psoriasis: A mendelian randomization study. JAMA Dermatol. 159, 275–280 (2023).

Williams, D. M., Finan, C., Schmidt, A. F., Burgess, S. & Hingorani, A. D. Lipid lowering and Alzheimer disease risk: A mendelian randomization study. Ann. Neurol. 87, 30–39 (2020).

Harrison, S. C. et al. Genetic association of lipids and lipid drug targets with abdominal aortic aneurysm: A meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 26–33 (2018).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: The STROBE-MR statement. JAMA 326, 1614–1621 (2021).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Paternoster, L. et al. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of 21,000 cases and 95,000 controls identifies new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 47, 1449–1456 (2015).

Budu-Aggrey, A. et al. European and multi-ancestry genome-wide association meta-analysis of atopic dermatitis highlights importance of systemic immune regulation. Nat. Commun. 14, 6172 (2023).

Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R. & Rücker, G. Meta-analysis with R (Springer, Cham, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21416-0.

Graham, S. E. et al. The power of genetic diversity in genome-wide association studies of lipids. Nature 600, 675–679 (2021).

Borén, J., Taskinen, M.-R., Björnson, E. & Packard, C. J. Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in health and dyslipidaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 577–592 (2022).

Ridker, P. M. LDL cholesterol: Controversies and future therapeutic directions. Lancet 384, 607–617 (2014).

Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 111–188 (2020).

Grundy, S. M. et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 139, e1082–e1143 (2019).

Yarmolinsky, J. et al. Association between genetically proxied inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase and epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA 323, 646–655 (2020).

Huang, W., Xiao, J., Ji, J. & Chen, L. Association of lipid-lowering drugs with COVID-19 outcomes from a Mendelian randomization study. eLife 10, e73873 (2021).

Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1712–1721 (2021).

Emdin, C. A., Khera, A. V. & Kathiresan, S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA 318, 1925–1926 (2017).

Burgess, S., Daniel, R. M., Butterworth, A. S. & Thompson, S. G. & EPIC-InterAct Consortium. Network Mendelian randomization: Using genetic variants as instrumental variables to investigate mediation in causal pathways. Int J Epidemiol 44, 484–495 (2015).

Carter, A. R. et al. Mendelian randomisation for mediation analysis: Current methods and challenges for implementation. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36, 465–478 (2021).

Relton, C. L. & Davey Smith, G. Two-step epigenetic Mendelian randomization: a strategy for establishing the causal role of epigenetic processes in pathways to disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 161–176 (2012).

Ahola-Olli, A. V. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci influencing concentrations of circulating cytokines and growth factors. Am J Hum Genet 100, 40–50 (2017).

Sanderson, E. Multivariable mendelian randomization and mediation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Med. 11, a038984 (2021).

Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 693–698 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Metabolic profiling of angiopoietin-like protein 3 and 4 inhibition: A drug-target Mendelian randomization analysis. Eur. Heart J. 42, 1160–1169 (2021).

Della Badia, L. A., Elshourbagy, N. A. & Mousa, S. A. Targeting PCSK9 as a promising new mechanism for lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Pharmacol. Ther. 164, 183–194 (2016).

Kim, Y. U., Kee, P., Danila, D. & Teng, B.-B. A critical role of PCSK9 in mediating IL-17-producing T cell responses in hyperlipidemia. Immune Netw 19, e41 (2019).

Barcena, M. L. et al. The impact of the PCSK-9/VLDL-receptor axis on inflammatory cell polarization. Cytokine 161, 156077 (2023).

Lee, J. S. et al. PCSK9 inhibition as a novel therapeutic target for alcoholic liver disease. Sci Rep 9, 17167 (2019).

Ruscica, M. et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS-3) induces proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) expression in hepatic HepG2 cell line. J Biol Chem 291, 3508–3519 (2016).

Lee, Y. S. et al. IL-32γ suppressed atopic dermatitis through inhibition of miR-205 expression via inactivation of nuclear factor-kappa B. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 146, 156–168 (2020).

Danso, M. O. et al. TNF-α and Th2 cytokines induce atopic dermatitis-like features on epidermal differentiation proteins and stratum corneum lipids in human skin equivalents. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 1941–1950 (2014).

Salimi, M. et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2939–2950 (2013).

Raap, U. et al. Circulating levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlate with disease severity in the intrinsic type of atopic dermatitis. Allergy 61, 1416–1418 (2006).

Toyoda, M. et al. Nerve growth factor and substance P are useful plasma markers of disease activity in atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 147, 71–79 (2002).

Takano, N., Sakurai, T., Ohashi, Y. & Kurachi, M. Effects of high-affinity nerve growth factor receptor inhibitors on symptoms in the NC/Nga mouse atopic dermatitis model. Br. J. Dermatol. 156, 241–246 (2007).

Holmes, M. V., Richardson, T. G., Ference, B. A., Davies, N. M. & Davey Smith, G. Integrating genomics with biomarkers and therapeutic targets to invigorate cardiovascular drug development. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 435–453 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We extend our profound gratitude to the researchers who generously shared their Genome-Wide Association Study data, making this investigation possible. We are especially thankful to the participants and dedicated teams behind the UK Biobank, FinnGen consortium, Biobank Japan, and the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Their commitment to advancing science and contributing invaluable resources has been instrumental in driving this research forward.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qinwang Niu: Writing an original draft, Software, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, and Conceptualization. Tongtong Zhang: Software, Data Source, and Methodology. Nana Zhao: Writing an original draft, Supervision, and Conceptualization. Rui Mao: Writing an original draft, Software, Methodology, and Visualization. Sui Deng: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – rivised draft, Funding acquisition, Software, and Visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, Q., Zhang, T., Mao, R. et al. Genetic association of lipid and lipid-lowering drug target genes with atopic dermatitis: a drug target Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 14, 18097 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69180-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69180-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Real-world data and Mendelian randomization analysis in assessing adverse reactions of rilonacept

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2025)