Abstract

Greenhouses located at high latitudes and in cloudy areas often experience a low quality and quantity of light, especially during autumn and winter. This low daily light integral (DLI) reduces production rate, quality, and nutritional value of many crops. This study was conducted on Sakhiya RZ F1 tomato plants to evaluate the impact of LED lights on the growth and nutritional value of tomatoes in a greenhouse with low daily light due to cloudy weather. The treatments included LED growth lights in three modes: top lighting, intra-canopy lighting, and combined top and intra-canopy lighting. The results showed that although the combined top and intra-canopy lighting reached the maximum increase in tomato yield, exposure to intra-canopy LED lighting alone outperformed in tomato fruit yield increase (28.46%) than exposure to top LED lighting alone (12.12%) when compared to no supplemental lighting during the entire production year. Intra-canopy exposure demonstrated the highest increase in tomato lycopene (31.3%), while top and intra-canopy lighting exhibited the highest increase in vitamin C content (123.4%) compared to the control. The LED light treatment also had a very positive effect on the expression of genes responsible for metabolic cycles, including Psy1, LCY-β, and VTC2 genes, which had collinearity with the increase in tomato fruit production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic and environmental factors influence growth and development of plants and in the absence of genetic restrictions, environmental factors including nutrition, cultivation date, as well as ambient light conditions determine plant characteristics1. Among these factors, light is one of the most crucial limiting ones for greenhouse production during the winter season in enhancing plant growth and biomass production2. Light changes during the day, not only in the amount of photons or intensity but also in the quality of wavelengths and colors. These changes can provide plants with crucial and ecologically valuable information3.

Changes in light quality greatly affect growth, especially through photosynthesis; however, light contains signals capable of conveying information to the plant that is used to process energy and the surrounding environment4. Light triggers certain signaling pathways and photoreceptors, leading to epigenetic changes under the interaction of light with transcription factors5. Indeed, the role of light-activated factors such as PAR1 (phytochrome rapidly regulated 1), PHYA (phytochrome A), PHYB (phytochrome B), and PIFs (phytochrome interacting factors) in the development of chromoplasts and accumulation of carotenoids in fruits like tomatoes during development and ripening remain to be determined in the future studies6. Naturally, the direct radiations from sunlight used for this purpose have a wavelength between 300 and 2500 nm, among which the spectrum of visible light is between 380 and 780 nm; however, the wavelength of active radiation (PAR) used for photosynthesis in plants is between 400 and 700 nm.

A lack of light usually leads to a decrease photosynthesis and reduction in the growth and development of plants in controlled environments such as greenhouses. At these circumstances, the productivity of greenhouse crops can be effectively increased by using supplementary (artificial) lights from new light sources. In fact, this increase in productivity will be due to the daily increase in the net absorption of photosynthesis using artificial light called daily light integral (DLI). DLI is the number of photosynthetically active photons delivered to a specific area over 24 h which may improve both yield and quality of tomato particularly when the natural light penetrated the greenhouse is not enough7,8. During the night, artificial light is the only means of signal perception and light intensity-dependent photosynthesis in the context of plant production.

LED lamps have recently been used as an alternative to sodium and halogen lamps in greenhouse crops, showing good potential for future adaptation9. Due to the unique advantages of LED lamps10,11, it is assumed that the efficiency and use of LED lamps are already double that of high-pressure sodium lamps (HPSs). Gomez et al.12, with an experimental design comparing LED supplemental light between plants (intra-lighting) and high-pressure sodium lamps above the plant in the greenhouse of tomato production, stated that the use of supplemental light in the greenhouse provided early fruit production (24–26 days earlier), higher number of harvested fruits and total fruit weight. The electrical conversion efficiency of LED lights in fruit biomass was 75% higher compared to high-pressure sodium ones. LEDs showed a high potential to achieve the goal of increasing profitability and sustainability in the greenhouse industry and as a good alternative to high-pressure sodium lamps12.

Brazaitytė et al.13 investigated the importance of the time for using supplementary LED lights on tomato growth, the number of fruits, and tomato yield. According to this study, supplementary light on tomatoes in December and January was relatively more beneficial, but for the plants cultured in March and later in spring and with the improvement of natural light conditions, supplementary light had no effect, or the effect of supplementary light decreased13.

The direction of supplementary light and the ratio of red to blue LED lamps for greenhouse tomato production have been also investigated and the results showed that the greatest production of biomass (including fruit) occurred with a light ratio of 19–1, red to blue, while the greatest number of fruits was produced in lights with a ratio of 5–1, red to blue lights14. Ouzounis et al.15 also found that exposure of tomato plants to a combination of red and blue light (88% red and 12% blue) reduces leaf morphological abnormalities and increases plant biomass. When plants were under 100% red light, all genotypes showed leaf twisting that was either upward or downward15. It seems that adding 6–24% blue light is enough for the highest increase in tomato growth and yield16.

Paponov et al.17 investigated the effects of supplementary light between plants (intra-lighting) on tomato fruit growth. They announced that using LED between plants particularly at night led to a faster fruit growth at night and a higher tomato biomass and fruit weight associated with enhancing root activity and root pressure providing water for fruit development at night. These attributes were also achieved by increasing the total assimilates available for fruit growth through stimulating photosynthetic rates in the lower-canopy leaves and preventing their premature senescence17. They showed that plants with interplant LED lighting had increased tomato fruit yield by 21% and exuded more sapwood compared to control plants. The analysis of wood sap showed that in the interplant LED light treatment, the levels of jasmonic acid increased up to three times compared to the levels in control plants, but the interplant supplemental light had no significant effect on other hormones’ concentrations. They finally stated that LED supplemental light does not only lead to an increase in photosynthesis in plants, but light is also a signal that controls physiological, morphological, and biochemical changes in the growth as well as development of tomato plants. LED lighting allows plants to adapt their responses to changes in environmental light and ultimately increases and stabilizes the quantity and quality of the tomato product17.

Most of the LED lamps currently used for top and inter-lighting in tomatoes are constructed with red (80–90%) and blue diodes (10–20%) to match the red and blue wavelengths that are most efficiently absorbed by photosynthetic pigments and for the optimum growth and yield in tomato production16,18. This will result in R: FR ratios that are higher than those of natural daylight. Recent investigations have also shown that far-red light (700–750 nm) can contribute to crop photosynthesis19. Furthermore, it seems FR radiation significantly increases the fraction of dry mass partitioned into fruits and this increase was shown to be the main explanation for yield increase under additional FR radiation in tomatoes20,21. Shifting dry mass accumulation to fruits may also influence the fruit quality of tomatoes in areas where the fruits have a poor quality of taste and flavor compared to in-season field-grown tomatoes22.

Greenhouse development programs have been aimed at increasing productivity, efficiency, and water consumption management in agriculture based on the sustainable development goals proposed by the United Nations to develop sustainable solutions to increase food production in the face of climate change without increasing land use. However, seasonal variation of light is considered a common problem in greenhouse production in northern areas with cloudy periods. In this area and on an overcast day, insufficient quality and intensity of light enter the greenhouse, and besides, a short duration of lighting per day may impose several limitations on photosynthesis23, fruit set and growth, and also may postpone fruit coloring in tomatoes, resulting in a reduction in the efficiency of greenhouse production. Therefore, supplemental lighting using light-emitting diodes during days or only at nights has been recently considered in industrial greenhouses to overcome these restrictions in natural lights.

The literature review shows that there are extensive studies on the application of LED lights on the growth and production and also on the fruit quality of different cultivars of tomato in experimental and industrial greenhouses with an almost optimum combination of red and blue lights with or without addition of far-red light. However, the data on whole-plant responses to light environments during a long period of production time are extremely limited. The effect of LED light position, i.e. exposure from the top compared to the middle of the plant (intra-canopy), has not been investigated on tomato performance during the production year. In addition to this lack of enough information, in this study, we also considered that LED light would probably affect the expression of genes responsible for the quality characteristics of ripe tomatoes, such as the content of antioxidants and medicinal metabolites, including lycopene. Therefore, considering the high nutritional and medicinal value of tomato and the economic benefits of tomato and its products on the one hand, and on the other hand, the lack of enough natural light in areas such as high latitudes of the world or cloudy conditions which prevent continuous production and tomato color development, this study was conducted. The aims were (1) to evaluate the effect of LED lighting on quality characteristics and yield performance of tomatoes simultaneously in an industrial greenhouse located in cloudy weather without enough lights during the short days of the year, (2) to compare the position of top-lighting versus intra-canopy lighting in the response of a commercial cultivar of tomato to LED lighting during the entire year of production and, (3) to explore the possible modifications in the expression of some indicative genes of tomato's metabolic and antioxidant cycles and also their relation to fruit yield and quality.

Material and methods

Plant material and greenhouse condition

Sakhiya RZ tomato seedlings (with round and large fruit type up to 250 g, with long shelf life and unlimited plant growth, prepared by Rijk Zwaan company in the Netherlands) were planted in an area of 5000 square meters in the greenhouse of Dasht-e Naz Sari Agricultural Company located in a cloudy condition in the north of Iran (36° 38′ 09″ N and 53° 11′ 37″ E, Mazandaran province, Iran) in rows with spacing 1.6 m and a distance of 30 cm on the rows. Climatic parameters within the greenhouse including temperature, humidity and DLI in each month of the year are presented in Table 1. Cloudy days were also measured in terms of how many eighths (Okta) of the sky was covered in cloud, and when it was 8 oktas, the sky was considered overcast. The total solar energy (Mega-Joule) received per square meter per month of the greenhouse was also calculated through an electrical assembly consisting of a solar cell and a galvanometer (Yokogawa Electric Works Ltd). The plants were treated with LED light panels comprised of 70% red (660 nm), 20% blue (460 nm) and 10% far-red (730 nm) (Manufactured by Golnoor Company, Iran, Fig. 1a) before flowering in October. The spectral composition of the light panels is also presented in Fig. 1. These panels were considered as the ones with the optimum level of wavelengths combination for growing tomatoes within the commercial greenhouse based on the literature recently reviewed21,24.

The plants were drip irrigated with a complete nutrient solution based on standardized recommendations containing: 17.81 mM NO3− from Ca(NO3)2, 0.71 mM NH4+ and 1.74 mM P from NH4H2PO4, 9.2 mM K from KSO4, 4.73 mM Ca from Ca(NO3)2, 2.72 mM Mg and 2.74 mM S from MgSO4. Trace elements nutritional concentrations were as follows: 15 µmol Fe from Iron (Fe) EDTA chelate, 10 µmol Mn and 5 µmol Zn from Manganese (Mn) EDTA chelate and Zinc (Zn) EDTA chelate, respectively, 30 µmol B from H3BO3, 0.75 µmol Cu from Cupper (Cu) EDTA chelate, and 0.5 µmol Mo from Na2MoO4. In the nutrient solution, there was 2.6 mS cm−1 electrical conductivity with a pH of 5.8.

Experimental design and light treatments

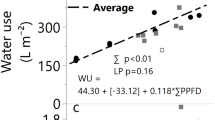

The experiment was conducted as a randomized complete block design, and the treatments included plants receiving light from LEDs and plants without receiving light through LED lights. The growth lights used in this experiment were applied as four treatments performed in four repetitions with 30 plants each. The applied treatments included (a) control (natural day light without exposure to LED growth light), (b) exposure from the top of the plants by adjusting the distance between the lamp and the plant by 40 cm, (c) lighting from among the plants (intra-canopy lighting) with close contact of the leaves and stems to the lamp, and finally (d) exposure from above and among the plants (combination of b and c), simultaneously (Fig. 1b–d). There were 10 m interspaces between the treatments within each replication and three rows (4.8 m) between treatment blocks within the cultivation area to prevent confounding of the treatments. Irradiance was emitted from both sides of the lamps with a PPFD of 120 μmol m–2 s–1 PAR on the leaf surface of the plants in different LED treatments away from the lamps. The photoperiod was set for 14 h from 06:00 am to 8:00 pm and was fixed during 9 months of the experiment from November to July. For intra-canopy lighting, light fixtures were located at the 1.7 m from the bed in close contact to the leaves and for top-lighting, they were adjusted 40 cm above plants. Positions of the LEDs were changed regularly during the growth period as the plant height increased or the plants were lowered to keep the irradiation level constant during the year.

The method of sampling for the estimation of parameters

For biometric evaluation, 10 plants among 30 established ones within each of 4 replications (in total 40 plants) were selected randomly, and the number and yield of tomatoes were measured weekly on these plants during the whole period of fruit harvest (9 months). Sampling for determining fruit dry weight, vitamin C, and lycopene content, as well as RNA expression, was performed on fruits and leaves collected randomly from the same plants for all light treatments at the end of each month. The fruits used for extraction of metabolites and RNA included ten fresh and fully red ripe tomatoes, with at least one from each harvest week during a month.

Analysis of production and quality parameters

The number and yield of tomato

The number and weight of harvested tomatoes from 10 sampled plants in each 4 replications were measured separately and weekly from November 5 to July 11 for 45 weeks. Then, the average number of fruits, single fruit weight and total fruit weight (yield) per plant and per square meter were calculated and used for analysis. This study was performed in an industrial greenhouse; therefore, we complied with our relevant institutional and national standards, as well as international guidelines including the IUCN Policy statement on research. The study was conducted without involving species at risk of extinction based on the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Vitamin C extraction and analysis by HPLC

The amount of vitamin C was measured for the end of January harvest from the fruits of selected plants. For this, ten fresh tomatoes were chosen randomly from those harvested under the treatments, and then were mixed by a blender from which two grams of the extract was taken, and two milliliters of 3% metaphosphoric acid were added. Then, it was placed in a sonicator for 30 min, after which it was centrifuged at 2604×g for 15 min. The upper phase was filtered with a 45 µM hydrophilic PTFE filter, and 10 µl were injected into a liquid chromatography device equipped with a diode array detector (Agilent 1090 HPLC Systems) and a C18 column (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) and the chromatogram set at 254 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1). For the mobile phase, 30 mM phosphoric acid (Merck, Germany) in nano water was utilized at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. To prepare the standard solution, two grams of ascorbic acid (Merck, Germany) were dissolved in one liter of 3% metaphosphoric acid (Merck, Germany). The result in terms of micrograms of vitamin C per g of tomato fresh weight was obtained from the standard curve25.

Lycopene extraction and analysis by spectroscopy

As described by Anthon and Barrett26, 12.5 ml ethanol, 12.5 ml acetone, and 25 ml hexane were added to five grams of tomato extract as explained above for vitamin C analysis. This mixture was blended in a shaker incubator at 300 rpm for 30 min. Then, 10 ml of distilled water was added to it, and the mixing continued for another 5 min. After a few minutes, the upper phase was poured into a cuvette and read with the wavelength of 503 nm in a spectrophotometer (Hitachi, U-1800, Tokyo, Japan). The spectrophotometer was blanked with hexane, and then the amount of lycopene was obtained from the standard curve in terms of micrograms of lycopene per g of tomato fresh weight26.

Total RNA extraction and quantitative real‑time PCR

RNA extraction from tomato fruits and leaves

The leaf and fruit samples were collected monthly from the first month of fruit ripening in November to the first of July from the greenhouse and stored at − 80 °C after fast-freezing with liquid nitrogen. Each month, sampling was done on 10 plants randomly selected from 30. Three fully expanded leaves from each plant exposed to LED light treatments (receiving at least 120 µmol m−2 s−1 from LED lights) were cut and 1 to 3 ripe fruits were chosen from harvested ones for further analysis. For RNA extraction, whole leaves and well-ripe red fruits described above and frozen in four replications were used.

RNA extraction from leaf and fruit material was performed using RNA extraction kit® (rnabiotech. Co., Iran). Briefly, the leaf or fruit material was ground in liquid nitrogen, CTAB buffer (2% CTAB, 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, 1.4 M NaCl, 1% sodium sulphite, 2% PVP) was added and then chloroform extraction was carried out. RNA from this extraction was precipitated with 4 M LiCl and passed through a QIAGEN RNeasy column extraction with on-column DNase treatment (QIAGEN). RNA quality and quantity were measured using the Nano Vue plus nano spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and verified using a RNA agarose gel (1%) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Since the LED treatments were constant during the production year, when the effect of light treatments reached the maximum in terms of yield potential compared to the control condition (without LED light application) at the end of January (see the results), the extracted RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. The aim was to determine whether there is collinearity between the light treatment with the highest potential effect on tomato fruit yield and the expression of indicative genes involved in the production and antioxidant characteristics of tomato fruit.

Selection and quantitative expression of candidate genes

A set of six candidate genes from the two tissue types of fruits and leaves was selected: first, four genes were chosen for their potential to significantly reflect the effect of supplemental lighting, as identified in the literature review. These genes included LCY-B27; Gene ID: 544104, (Lycopene β-cyclase, from carotenoid production cycle), Psy128; Gene ID: 543988 (Phytoene synthase, from lycopene production cycle), VTC229; Gene ID: 828792 (GDP-L-galactose-phosphorylase- 1 homolog, from vitamin C production cycle) expressed in fruits and CRY230; Gene ID: 543596 (Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 2 from antioxidant production cycle) expressed in leaves. Second, two genes including SFT1; Gene ID: 101246029 (Single Flower Truss) and GAME4; Gene ID: 101261488 (Glycoalkaloid Metabolism 4 from the production cycle of plant steroids) were chosen based on their functional predictions and phenotypic outcomes on tomato fruit production and quality31, respectively, expressed in leaves (Table 2).

For single-strand cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription (ReverTra Ace-α-® kit (AddBio Inc., Korea)). The resulting products were diluted 20-fold and then used as a template for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with gene-specific primers. Subsequently, qRT-PCR was performed using a 2X Real-time PCR smart mix (Solgent, Korea) in a Step One real-time system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The thermal cycling conditions were set to 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s and finally at 72 °C for 40 s for 40 cycles. To quantify the expression level of genes involved in the selected pathways, the actin housekeeping gene was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis of data

The yield data of tomato, as well as the data on lycopene and vitamin C, were tested for normality of the data and residuals. Subsequently, the data were analyzed according to a randomized complete block design with four replications using ANOVA in SAS. The means were compared using the LSD test in SAS software. The time series graph of fruit production and tomato yield was also plotted using Excel software. To assess multivariate collinearity among traits, especially between molecular characteristics and LED treatments, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using StatGraphics (ver. 9.3).

For the gene expression assay, each sample of plant leaves or fruits was analyzed in duplicate as technical replicates per each four biological replicates, and the expression was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method. Relative quantification was performed using QuantStudio™ Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The limit of quantitation (LoQ) for each mRNA studied was determined based on the principle of the minimum signal-to-noise ratio of 10, a typical constant used to define the minimum concentration at which an analyte can be reliably quantified. Therefore, LoQ was calculated as the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value that was 3.2 Ct units lower than the limit of blank (LoB) (Ct value detected in non-template controls, containing the primer pair and master mix, without RNA sample).

Results

The number and yield of tomato fruits

The ANOVA table (Table 3) shows a significant difference (p < 0.01) among the four light treatments in terms of the number, single fruit weight, and yield of tomatoes. At the end of the growing season, 146.6 fruits per square meter were produced by tomato plants without the use of LED lights (Table 3, Fig. 2) which was equivalent to 22.03 kg per square meter (Table 3, Fig. 3) and with 5.14% dry matter content (Table 3). In contrast, by applying the treatments of LED lights, the number of tomatoes per square meter reached 169.8, 196.9, and 206.6 in top-lighting, intra-canopy lighting, and the combination of both, respectively (Table 3). This increase in the number of fruits was equal to 24.7 kg of fruit per square meter in LED light exposure from the top with 5.41% dry matter content. In exposure from the intra-canopy lighting, it was equal to 28.3 kg per square meter, and in exposure from both intra- and top-lighting, it was equal to 28.8 kg per square meter (Table 3 and Fig. 3) with 5.98% and 5.99% dry matter content, respectively. Therefore, exposure to LED lights led to a maximum increase of 30.87% in tomato fruit yield during the whole production year, which is observed in the intra-top-lighting treatment. The lowest rate of increase in performance percentage is also seen in light exposure from the top, by 11.12% (Table 3). In contrast to the increase in the number of fruits and yield of tomato due to top- and intra-canopy lighting, the results showed that single fruit weight decreased by LED lighting compared to the control conditions (Table 3).

The cumulative tomato yield over the year shows that the separation and effect of different light treatments as the percentage of increase in yield compared to control treatment (Fig. 4) started in January and reached the peak of changes in February (more than 150% increase in yield in the treatment of LED lighting from top and intra-canopy of the plants compared to the control condition). However, there was an average increase of 30.87% in tomato yield due to LED lighting treatment (both top and intra-canopy lighting) over the whole year (Table 3). This significant effect of LED lighting can be seen from March to May, and then the effect of supplemental lighting decreased (Fig. 4).

Mean comparisons (Table 3) shows that although the number of fruits was significantly different between the two treatments of LED including lighting from both the intra-canopy and top with lighting from the intra-canopy alone; this difference in the number of tomato fruits did not lead to a significant increase in the tomato fruit yield. In other words, exposure to LED lighting from the top of the plants in addition to the exposure from the intra-canopy had possibly a positive effect on flower maintenance and increased the formation and number of tomato fruits, but this was not so effective on the yield and single fruit weight of tomato to justify adding LED lighting from the top of the plants.

Vitamin C and lycopene contents

The ANOVA table (Table 3) shows the significant difference (p < 0.01) among the four light treatments in terms of quality characteristics of vitamin C and lycopene contents of fruits. As the mean comparisons of data in Table 3 show, LED light treatments led to a significant increase in vitamin C and lycopene contents of the tomato cultivar Sakhiya. The highest amount of vitamin C in tomato extract was observed when the plants were exposed to LED lighting treatment from both the top and intra-canopy (206.4 µg g−1 FW), which shows an increase of 123.4% compared to the control treatment. Intra-canopy lighting was in the second place in this regard (91.7% increase). In contrast to vitamin C content, the highest amount of lycopene was observed when the plants were exposed to LED from the intra-canopy lighting (267.2 µg g−1 FW), which shows a 31.3% increase compared to the control treatment. Both treatments of top lighting and top and intra-canopy lighting were in the second place of increase in lycopene content (13.1 and 15.9%, respectively) with no significant difference (Table 3).

The effect of LEDs on biosynthetic genetic pathways

The expression pattern of LCY-B (from the carotenoids production cycle) in tomato fruits was dramatically higher in plants under intra-canopy lighting than those under control and top lighting conditions. According to the results of this study, the expression of the LCY-B gene increased by 2.39 and 1.902 times as a result of LED light treatments from intra-top lighting, as well as intra-canopy lighting, respectively, compared to the control conditions of the greenhouse without LED treatment. However, exposure to top LED lighting led to a decrease in LCY-B gene expression (Fig. 6).

Based on the findings of this study, the expression level of the Psy1 gene increased strongly due to LED light treatments, so that the range of expression of this gene under LED light treatments from intra-top lighting, intra-canopy lighting, and top lighting was respectively 5.59, 5.02, and 1.75 times higher than the conditions of the control greenhouse without LED treatment (Fig. 6).

VTC2 (from the vitamin C production cycle) expression was dramatically higher in plants under intra-canopy lighting than those under control light and top-lighting conditions. The expression of this gene increased strongly due to intra-top LED light treatments, as well as intra-canopy lighting (it was 5.507 and 4.706 times higher than the control conditions, respectively) (Fig. 6). This is while due to top lighting, the expression of this gene almost did not change compared to the control conditions of the greenhouse (the ratio is 0.97). These results show that only intra-canopy lighting has the potential to increase the expression of this gene and improve vitamin C content.

GAME4 and CRY2 genes were significantly over-expressed only under the treatment of both top and intra-canopy lighting (5.14 and 1.99 times higher than the condition of without LED light treatment, respectively), while by intra-canopy lighting and also top lighting alone, the gene expression decreased (Fig. 6).

Based on the results of this study, there were significant changes in the expression of the SFT gene as a result of LED light treatments, so that the expression of this gene under LED light treatments from intra- and top lighting, intra-canopy lighting, and top lighting decreased and was 0.275, 0.437 and 0.188 times, respectively, compared to the control conditions of the greenhouse without LED treatment (Fig. 6).

Multivariate data analysis

Figure 7 shows a very significant correlation between the expression of genes, including Psy1, LCY–B, and VTC2, and the number of tomato fruits and fruit yield based on the biplot analysis. Also, based on the figure, each light environment is placed in a separate quarter of the plot, and as indicated in the environments L1 and L2 in which intra-canopy lighting has been used, most of the variation among traits (PC1: 73.37%) is justified. Overall, high collinearity is observed between intra-canopy lighting and the expression of all genes except SFT1 (Fig. 7).

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that, although the combination of top-lighting and intra-canopy lighting reached the maximum increase in tomato yield and dry matter content, exposure to intra-canopy LED lighting alone led to a higher increase in tomato fruit yield through increasing the number of fruits maintained (and not through single fruit weight) throughout the entire production year (28.46%) compared to exposure to top LED lighting alone (12.12%). This clearly shows the advantages of intra-canopy lighting over top lighting. Using both top-lighting and intra-canopy lighting provides a more uniform light distribution over the leaves in the canopy, which can enhance crop photosynthesis and growth. Therefore, a combination of intra-canopy and top lighting is recommended to reduce canopy heterogeneity in absorbed light. However, intra-canopy lighting may result in 8% higher total light absorption than top lighting32, making intra-canopy lighting the preferred choice. On the other hand, it seems that since tomato is grown at high planting densities within the greenhouse, this high-wiring canopy results in a strong shading effect on the leaves beneath the upper plant canopy, leading to a dramatic decrease in photosynthesis rate in the lower plant canopy. Consequently, crop yield potential increases with intra-canopy lighting more than top lighting33,34. These results show an increase in tomato yield more than the yield increase observed in the study of Paponov et al.17 on the intra-canopy lighting of the Flavance variety of tomato, which was a maximum of 13–24%17. They used LED lamps with a ratio of 80/20, red/blue, and measured the yield in a short period of time. Apart from varietal differences, adding 10% far-red light in our study may have also improved the response to intra-canopy lighting. Jiang et al.35, also reported that when greenhouse-grown tomato plants were supplied with supplemental LED intra-lighting in a combination of red and white LEDs without using far-red, a 14% increase in fresh yield was observed in a brief period of time as compared to control conditions35.

As indicated in Fig. 5, the more overcast days there are in the growing season, the less solar energy is received in the greenhouse. Comparing the data in this figure with the changes in tomato yield due to the influence of LED treatments in Fig. 4 reveals a strong dependence between the magnitude of the increase in crop yield due to artificial lighting and the number of overcast days, but with 2 months delay in response. The delay in observing the highest response to LED lighting compared to the maximum number of cloudy days may be justified physiologically by the time needed for translocation of assimilates to the new fruits set after the stimulating process of LED lighting. Therefore, it may be concluded that the effect of LED lighting in months with a higher number of overcasting days (November, December, and January) is more pronounced than in the other months with less overcasting sky (March, April, and May). In accordance with this observation, Lanoue et al.36 reported that as the natural DLI increased, the advantage from growth under LED lighting diminished. It means carbon export/photo assimilate translocation occurs at the highest rate under exposure to artificial light (120 umol/m2/s) when lacking solar radiation. Thus, LED lighting may be most beneficial during periods of low natural lighting and lower DLI (November to March) and less valuable as solar DLI increases (after March) (Table 1). Similarly, in the study of Brazaitytė et al.13, it was reported that the percentage of changes in tomato fruit yield was higher during December and January12 which overlaps with our results in this study. However, some differences come from different cultivars used in the two studies, earlier installation of LED light, and different geographical conditions in the Brazaitytė et al. report.

Several reasons support why intra-canopy lighting may outperform top lighting in tomato production while it proved lower DLI compared to top lighting (Table 1). The spectral properties of light activate phytochrome signals in leaves at lower canopy positions37. This will suppress the senescence of the leaves and increase the efficiency of light consumption by the lower leaves, thereby increasing the overall growth of the plant and improving the absorption and storage of sugars in the fruit during fruit filling. Blue light received in deeper canopy via intra-canopy lighting is able to increase carbon export, the process responsible for transporting photo-assimilate from the leaf to growing sinks such as fruits36,38. In addition, supplemental LED lighting at lower canopy positions likely increases root pressure, which increases the water supply to fruits and subsequently increases fruit growth and weight gain when the lights are on at night17,39. Another reason for the superiority of intra-canopy lighting over top lighting in tomatoes may be the single fruit weight loss (Table 3) under the RB due to the spectral effect from higher R: FR or blue light emitted from the top. In the middle or lower canopy, the FR light generated by the natural shading from upper leaves is insufficient27. Adding 10% FR light to the RB in the lights constructed for this study used in intra-canopy lighting could improve the single fruit weight and yield, perhaps due to FR lighting in deeper tomato canopies.

According to the results of Table 3, there is a significant difference (p < 0.01) among the four light treatments in terms of quality characteristics of vitamin C and lycopene contents of fruits. It is deduced that top and intra-canopy LED lighting led to the highest increase of 123.4% in the amount of vitamin C in tomato extract compared to the control treatment, and the highest increase of 31.3% in the amount of lycopene was observed when the plants were exposed to LED from the intra-canopy lighting. It seems that a higher accumulation of ascorbate (vitamin C) in the leaves and fruits of tomatoes is highly influenced by higher light intensity respective to more DLI40 and higher blue light proportion; therefore, top and intra-canopy LED lighting simultaneously provides a good approach to improving the vitamin C content of tomatoes. In contrast, lycopene accumulation is induced by the red/far-red ratio and through a phytochrome-mediated signaling pathway41. Therefore, intra-canopy LED lighting can be used as an effective method to increase lycopene content and preserve the nutritional quality of tomatoes by LED-derived gene expression regulation. Dannehl et al.42 also showed that lycopene and lutein contents in tomatoes exposed to top LED-lighting were respectively 18% and 142% higher compared to the control condition42. However, tomatoes exposed to blue LED lights contained up to twice as much vitamin C as the tomatoes not exposed to the LEDs28.

Diets rich in vitamin C and lycopene prevent heart diseases due to the reduction of bad cholesterol43. In addition, both vitamin C and lycopene are considered anti-ageing, which reduces age-related diseases44. It has also been found that people who receive sufficient amounts of vitamin C and lycopene in their diet are less prone to cancer and infectious diseases than others45. All this scientific evidence shows that any major change in vitamin C and lycopene content of tomatoes can have a great impact on the general health of society. The per capita consumption of tomatoes in the world is about 25 kg, which is three times higher than the per capita consumption of apples and two times higher than the per capita consumption of citrus fruits. This statistic shows the importance of the world paying attention to the food quality of tomatoes. Therefore, taking into account that the use of supplementary LED lighting in the greenhouse led to a dramatic increase in vitamin C content (more than 120% increase) and a significant increase in lycopene content (more than 30%) in addition to the rise in the yield, may encourage the use of LED lights in greenhouse production of tomato.

In this study, one of our main goals was the evaluation of the plant's antioxidant properties in terms of both vitamin C and lycopene contents as potent antioxidants and genes responsible for the plant’s antioxidant pathways under LED lighting. LEDs have been shown to influence the expression of secondary metabolite biosynthesis in different plants by several studies. However, regarding genes, we tried to evaluate one key gene from several different metabolic cycles of the plant, including Psy1, LCY-B, GAME4, SFT, and VTC2 and open the way for further studies. The results of gene expression analysis showed that the LEDs greatly influenced all pathways of genes selected; however, their expression pattern differed with the position of the light panel.

The results showed that LCY-B was dramatically higher in tomato fruits in plants under intra-canopy lighting than those under control light and top lighting conditions (Fig. 6). Therefore, and probably, intra-canopy lighting has the potential to increase the expression of this gene and improve beta-carotene accumulation. Considering that in this study, the expression of the LCY-B gene increased as a result of intra-canopy LED exposure in the greenhouse, it can be concluded that supplemental LED exposure may lead to an increase and accumulation of beta-carotene in ripe tomato fruits. Lycopene β-cyclase (LCY-B) is a key enzyme involved directly in the synthesis of α-carotene and β-carotene through the cyclization of trans-lycopene46,47,48. As LCY-B catalyzes the cyclization of lycopene to produce β-carotene in the carotenoids cycle for producing β-carotene, it was a good candidate to assess its expression under LED light induction. Tuan et al.49 reported a higher level of carotenoid biosynthetic gene expression in Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn in white light compared to blue and red LEDs49.

In this study, quantitative data (Table 3) showed that LED supplemental exposure also had positive effects on the increase of lycopene; therefore, it seems that the supplemental exposure to light may lead to the expression increase of genes affecting lycopene production as well. This is reflected in Fig. 6 in which we demonstrated an increase of 5.59, 5.02, and 1.75 times from intra-top lighting, intra-canopy lighting, and top lighting respectively compared to the control condition (Fig. 6). This is consistent with the positive effect of intra-canopy lighting on increasing the expression of the PSY1 (phytoene synthase) gene in ripe fruits at a much higher extent. Probably, other genes affecting lycopene production, such as PDS (phytoene desaturase) and ZDS (zeta-carotene desaturase)46 are not exempt from this rule, which should be considered in future studies for further analysis.

Carotenoids play important role in plants for crucial processes such as photosynthesis, assembly and functioning of photosynthetic organs, photoprotection by dispersing excess light energy as heat, and removing free radicals. In addition, carotenoids add color to flower petals and ripe fruits to attract animals to pollinate and spread seeds50. Phytoene synthase (PSY) is one of the main determining enzymes in the biosynthesis pathway of carotenoids, and the increased expression of phytoene synthase was significantly induced under red LED light conditions mediated by phytochrome51. PSY catalyzes the primary and fundamental flux-controlling step of the carotenoid pathway. Three genes encoding PSY isoforms are displayed in tomato, PSY1 to PSY3. Uncolored phytoenes are converted into red lycopene by several desaturation and isomerisation steps. PSY1 was verified to be the main isoform in charge of phytoene production for carotenoid pigments in the chromoplasts of flower petals and fruit pericarp. It is one of the most highly expressed transcripts in ripe tomato fruits50,52. Furthermore, studies have shown that lycopene content in tomatoes has been strongly increased by the overexpression of phytoene synthase 1(PSY1)42. As described above, one of the major function of carotenoids in plants especially those in leaves is photoprotection against photooxidation damage due to intense light. In fact, through the nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ) process, carotenoids can scatter the excess light energy as heat. Also, Ezquerro et al. have found that when tomato seedlings grown under normal light (NL) were transferred to high light conditions, expression of genes encoding PSY1 and PSY2 and simultaneous production of carotenoids were up-regulated compared to control plants transferred for the same time to NL50. Since we saw an increase in the expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis of carotenoids such as Psy1, we can conclude that LED light as an excess light energy has triggered such a mechanism in the plant.

According to our results, we demonstrated that intra-top and intra-canopy LED lightings increased the expression level of the VTC2 gene (5.507 and 4.706 times higher than the control conditions) (Fig. 6), which corresponds to the results of vitamin C content in fruits (Table 3). The first devoted step for the synthesis of vitamin C in the d-mannose/l-galactose pathway is the conversion of GDP- l-galactose to l-galactose-1-phosphate, catalyzed by GDP-l-galactose-phosphorylase (GGP)53,54 and VTC2 encodes GDP-L-galactose phosphorylase55. The vitamin C content and the increase in light irradiation are strongly correlated with transcript levels of VTC2 and VTC554. In addition, according to Massot et al. suggestion (2010 and 2012), increasing the expression of each VTC2 gene leads to an increase in vitamin C content56,57.

In the present study, we did not measure the content and types of steroid alkaloids in tomato plants exposed to LED lighting; however, the expression of GAME4 responsible for the production of tomatidine58 increased strongly due to the simultaneous exposure to LEDs from both intra- and top lighting (5.14 times compared to the control conditions of the greenhouse). This decreased with intra-canopy lighting and exposure from the top of the plants (Fig. 6). About 100 steroid alkaloids have been found in different tissues and stages of tomato growth particularly in the leaves and immature green fruits58 encoded by a series of GAME genes. Steroidal glycoalkaloids act as phyto-anticipins and provide the plant with a defense against a wide range of pathogens59. However, some of them are also considered anti-nutritional substances in the diet60. The biological activity of glycoalkaloids is not limited to their toxicity. It is reported that they have anti-cancer, anti-cholesterol, anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, anti-fever, and overall antioxidant properties61. As tomato fruits ripen, steroid alkaloids undergo metabolic conversion to the non-toxic alkaloids like esculeoside A, which also boasts a myriad of physiological benefits, such as inhibiting tumor growth, lowering cholesterol, and reducing the occurrence of atherosclerosis62,63.

Based on our results, we observed an increase in the expression of the CRY2 gene under top and intra-canopy lighting compared to the control condition (Fig. 6). CRYs are flavin-containing photoreceptors found in bacteria and eukaryotes. Plant CRYs are photoreceptors for blue, green, and UV-A lights and regulate photomorphogenesis64. In tomatoes, two CRY1 genes: CRY1a and CRY1b; one CRY2 and one CRY3 gene have been isolated65. CRY2 controls the vegetative development, flowering time, and antioxidant content of tomato fruits, as well as the daily transcriptional profile of several genes, including PHY (phytochrome)66. Lopez et al. indicated that the expression of several tomato proteins is significantly affected by CRY2 overexpression and that light acting through CRY2 regulates the expression of several proteins. In particular, proteins involved in photosynthesis, photorespiration and plant stress accumulate differently65. As for GAME4, to induce the expression of CRY2, probably more DLI will be needed, which is not provided by intra-canopy or top lighting alone in this experiment. It seems that the effect of intra- and top LED lighting on CRY2 gene expression is associated with early flowering and also increasing the antioxidant content of the fruits67.

In contrast to the other five genes assessed, SFT (SINGLE FLOWER TRUS) expression was down-regulated to some extent under all LED treatments compared to the control condition. This had not been hypothesized before the experiment, as it is reported that the up-regulation of SFT may influence the expression of other genes responsible for flowering, tomato numbers, and yield68. This finding was achieved via the use of a mutant form of the gene (the sft gene), which was first described by Kerr69 as a single-gene mutation on the chromosome 3 leading to a reduced number of flowers per spike of tomato. The sft mutant gene plays a role in postponing the formation of flower meristem and reducing the number and formation of flower organs69.

The effect of LED light on the expression of the SFT gene had not been investigated before; however, the results of this study showing the reducing effect of LED light on the gene expression was unexpected, which may be interpreted by the cultivar dependency and complexity in SFT expression. In cultivated tomato, we know that flowering time is not influenced by photoperiod (but by integral light doses) and tomato is therefore considered a day-neutral plant. In photoperiod-insensitive cultivars of tomato (like Sakhiya in our experiment) and in the absence of expression of SELF PRUNING (SP) and SELF PRUNING 5G (SP5G), which normally play a flower-repressing role in long days, and FLOWERING LOCUS T-LIKE1 (FTL1), which plays a flower-activating role in short days in wild species70, SFT is the integrator of flowering signals cascading from endogenous and environmental conditions71. The environmental and/or endogenous signals that activate SFT synthesis are not well elucidated; however, it seems that SFT might be up-regulated in a leaf age-dependent pathway72,73. Also, although light intensity may promote early flowering in tomato, it is reported that high SFT/SP ratios can substitute for light intensity in tomato74. SFT itself has a complex and pleiotropic function for growth and termination with mediation of other genes activated in leaves in response to elevated SFT levels. Therefore, and taken together, there is a complex dynamic, temporal, and spatial expression of SFT in tomato leaves which is not simply interpreted75.

The results of gene expression analysis showed that the LEDs greatly influenced all pathways of genes selected; however, their expression pattern differed with the position of the light panel. Here we found that LED lighting especially intra-canopy lighting, has the greatest potential to trigger higher gene expression of different production cycles of tomato than top-lighting. The study of Park et al.76 also showed that the gene expression level of phenylpropanoid pathway genes is broadly variable in different exposure levels to LEDs76. It means that a wide variety of LEDs may have the ability to produce an overall change in expression.

In this study, one of our main goals was also to assess the effect of LED lighting on quality characteristics and yield performance of tomatoes simultaneously. Indeed, the highest expression of biosynthetic pathway genes under LED light may lead to the relatively highest accumulation of direct metabolites like LCY–B for beta-carotene accumulation and VTC2 for vitamin C accumulation or indirectly to a higher number of tomatoes and higher yield. This is reflected in Fig. 7, which shows a very significant correlation between the expression of genes, including Psy1, LCY–B, and VTC2, antioxidant content (indicated by vitamin C and lycopene contents), and the number of tomato fruits and fruit yield based on the biplot analysis. Also, based on the figure, a high collinearity is observed between intra-canopy lighting, lycopene content and tomato yield, and the expression of all genes except SFT. The reason for the increased expression of the genes and higher accumulation of metabolites under intra-canopy lighting might be because intra-canopy lighting is in the vicinity of the leaf surface and can better penetrate the plant’s lower canopy for better signaling when compared to top lighting alone. Overall, it is possible to increase both qualitative and quantitative characteristics of tomato fruits at the same time by applying LED lights as intra-canopy alone or by the combination of top and intra-canopy lighting.

The biplot displaying the relationship among the number (No. Fruit) and single fruit weight (SFW) of tomato, Yield, dry matter content (DMC), vitamin C (Vit. C) and Lycopene contents and the expression of genes affecting metabolic cycles (LCY-B, VTC2, GAME4, CRY2, SFT1 and PSY1). L1: Top-Intra lighting, L2: Intra-canopy lighting, L3: Top-lighting and C: control condition without LED exposure.

Conclusion

In the present study, the effects of three modes of LED lighting including intra-canopy lighting, top-lighting, and the combination of both were investigated on tomato yield performance. Also, the accumulation of lycopene and vitamin C and the expression of key genes responsible for tomato fruit formation and quality were assessed. The results showed that LED intra-canopy lighting outperformed top-lighting to accumulate significantly higher contents of lycopene and vitamin C and increase the number of tomatoes and yield. More uniform lighting within the canopy in intra-canopy lighting may increase carbon export to fruits, leading to higher yields. Moreover, simultaneous increases in the expression of LCY–B (for carotenoid accumulation), VTC2 (for vitamin C accumulation), and Psy1 (from the lycopene production cycle) contributed to the higher antioxidant properties of the fruit based on the multivariate data analysis. The results presented might provide a new strategy by using LEDs to enhance the commercial and nutritional value of tomatoes at the same time, especially in cloudy areas of the world which have not enough natural light irradiation.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this paper. The raw datasets produced in the current study are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ali, M. M., Yousef, A. F., Li, B. & Chen, F. Effect of environmental factors on growth and development of fruits. Trop. Plant Biol. 14, 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12042-021-09291-6 (2021).

Li, Q. & Kubota, C. Effects of supplemental light quality on growth and phytochemicals of baby leaf lettuce. Environ. Exp. Bot. 67, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.06.011 (2009).

Martinez-Garcia, J. F. & Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. Molecular mechanisms of shade tolerance in plants. New Phytol. 239, 1190–1202. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19047 (2023).

Hart, J. W. Light and Plant Growth Vol. 1 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Mishra, S. & Khurana, J. Emerging roles and new paradigms in signaling mechanisms of plant cryptochromes. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 36, 89–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2017.1348725 (2017).

Quian-Ulloa, R. & Stange, C. Carotenoid biosynthesis and plastid development in plants: The role of light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031184 (2021).

Matsuda, R., Yamano, T., Murakami, K. & Fujiwara, K. Effects of spectral distribution and photosynthetic photon flux density for overnight LED light irradiation on tomato seedling growth and leaf injury. Sci. Hortic. 198, 363–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.11.045 (2016).

Verheul, M. J. et al. Artificial top-light is more efficient for tomato production than inter-light. Sci. Hortic. 291, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2021.110537 (2022).

Hernández, R. & Kubota, C. Growth and morphological response of cucumber seedlings to supplemental red and blue photon flux ratios under varied solar daily light integrals. Sci. Hortic. 173, 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.04.035 (2014).

Olle, M. & Viršile, A. The effects of light-emitting diode lighting on greenhouse plant growth and quality. Agric. Food Sci. 22, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.23986/afsci.7897 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. Effects of light quality on CO2 assimilation, chlorophyll-fluorescence quenching, expression of Calvin cycle genes and carbohydrate accumulation in Cucumis sativus. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 96, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.03.010 (2009).

Gomez, C., Morrow, R. C., Bourget, C. M., Massa, G. D. & Mitchell, C. A. Comparison of intracanopy light-emitting diode towers and overhead high-pressure sodium lamps for supplemental lighting of greenhouse-grown tomatoes. HortTechnology 23, 93–98. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH.23.1.93 (2013).

Brazaitytė, A. et al. After-effect of light-emitting diodes lighting on tomato growth and yield in greenhouse. Sodinink. daržinink. 28, 115–126 (2009).

Deram, P., Lefsrud, M. G. & Orsat, V. Supplemental lighting orientation and red-to-blue ratio of light-emitting diodes for greenhouse tomato production. HortScience 49, 448–452. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.49.4.448 (2014).

Ouzounis, T. et al. Blue and red LED lighting effects on plant biomass, stomatal conductance, and metabolite content in nine tomato genotypes. In VIII International Symposium on Light in Horticulture 1134, 251–258 (2016).

Kaiser, E. et al. Adding blue to red supplemental light increases biomass and yield of greenhouse-grown tomatoes, but only to an optimum. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.02002 (2019).

Paponov, M., Kechasov, D., Lacek, J., Verheul, M. J. & Paponov, I. A. Supplemental light-emitting diode inter-lighting increases tomato fruit growth through enhanced photosynthetic light use efficiency and modulated root activity. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1656. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01656 (2020).

Davis, P. A. & Burns, C. Photobiology in protected horticulture. Food Energy Secur. 5, 23–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.97 (2016).

Zhen, S. & Bugbee, B. Substituting far-red for traditionally defined photosynthetic photons results in equal canopy quantum yield for CO2 fixation and increased photon capture during long-term studies: Implications for re-defining PAR. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 581156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.581156 (2020).

Ji, Y. et al. Far-red radiation increases dry mass partitioning to fruits but reduces Botrytis cinerea resistance in tomato. Environ. Exp. Bot. 228, 1914–1925. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16805 (2019).

Ji, Y. et al. Far-red radiation stimulates dry mass partitioning to fruits by increasing fruit sink strength in tomato. New Phytol. 228, 1914–1925. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16805 (2020).

Kim, H. J. et al. Supplemental intracanopy far-red radiation to red LED light improves fruit quality attributes of greenhouse tomatoes. Sci. Hortic. 261, 108985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108985 (2020).

Esmaeili, S. et al. Elevated light intensity compensates for nitrogen deficiency during chrysanthemum growth by improving water and nitrogen use efficiency. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14163-4 (2022).

Zhang, Y. T., Zhang, Y. Q., Yang, Q. C. & Tao, L. I. Overhead supplemental far-red light stimulates tomato growth under intra-canopy lighting with LEDs. J. Integr. Agric. 18, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(18)62130-6 (2019).

Lee, J. H. J., Jayaprakasha, G. K., Avila, C. A., Crosby, K. M. & Patil, B. S. Effects of genotype and production system on quality of tomato fruits and in vitro bile acids binding capacity. Food Sci. 85, 3806–3814. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15495 (2020).

Anthon, G. & Barrett, D. M. Standardization of a rapid spectrophotometric method for lycopene analysis. Acta Hortic. 758, 111–128. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2007.758.12 (2007).

Kim, D. & Son, J. E. Adding far-red to red, blue supplemental light-emitting diode interlighting improved sweet pepper yield but attenuated carotenoid content. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 938199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.938199 (2022).

He, R. et al. Supplemental blue light frequencies improve ripening and nutritional qualities of tomato fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 888976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.888976 (2022).

Ma, G. et al. Effect of red and blue LED light irradiation on ascorbate content and expression of genes related to ascorbate metabolism in postharvest broccoli. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 94, 97–103 (2014).

Ohgishi, M., Saji, K., Okada, K. & Sakai, T. Functional analysis of each blue light receptor, cry1, cry2, phot1, and phot2, by using combinatorial multiple mutants in Arabidopsis. PNAS. 101, 2223–2228 (2004).

Krieger, U., Lippman, Z. B. & Zamir, D. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 42, 459–463 (2010).

Schipper, R. et al. Consequences of intra-canopy and top LED lighting for uniformity of light distribution in a tomato crop. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1012529 (2023).

Trouwborst, G., Oosterkamp, J., Hogewoning, S. W., Harbinson, J. & Van Ieperen, W. The responses of light interception, photosynthesis and fruit yield of cucumber to LED-lighting within the canopy. Physiol. Plant. 138, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01333.x (2010).

Li, Q. et al. Effect of supplemental lighting on water transport, photosynthetic carbon gain and water use efficiency in greenhouse tomato. Sci. Hortic. 256, 108630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108630 (2019).

Jiang, C. et al. Photosynthesis, plant growth, and fruit production of single-truss tomato improves with supplemental lighting provided from underneath or within the inner canopy. Sci. Hortic. 222, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.04.026 (2017).

Lanoue, J. et al. Alternating red and blue light-emitting diodes allows for injury-free tomato production with continuous lighting. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1114 (2019).

Huber, M., Nieuwendijk, N. M., Pantazopoulou, C. K. & Pierik, R. Light signalling shapes plant–plant interactions in dense canopies. Plant Cell Environ. 44, 1014–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13912 (2021).

Lanoue, J., Leonardos, E. D. & Grodzinski, B. Effects of light quality and intensity on diurnal patterns and rates of photo-assimilate translocation and transpiration in tomato leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 756 (2018).

Verheul, M. J., Maessen, H. F. R. & Grimstad, S. O. Optimizing a year-round cultivation system of tomato under artificial light. Acta Hortic. 956, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2012.956.45 (2012).

Ntagkas, N., Woltering, E., Nicole, C., Labrie, C. & Marcelis, L. F. Light regulation of vitamin C in tomato fruit is mediated through photosynthesis. Environ Exp Bot. 158, 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.12.002 (2019).

Song, Y., Teakle, G. & Lillywhite, R. Unravelling effects of red/far-red light on nutritional quality and the role and mechanism in regulating lycopene synthesis in postharvest cherry tomatoes. Food Chem. 414, 135690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135690 (2023).

Dannehl, D., Schwend, T., Veit, D. & Schmidt, U. Increase of yield, lycopene, and lutein content in tomatoes grown under continuous PAR spectrum LED lighting. Front Plant Sci. 12, 611236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.611236 (2021).

Inoue, T., Yoshida, K., Sasaki, E., Aizawa, K. & Kamioka, H. Effects of lycopene intake on HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride levels: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Food Sci. 86, 3285–3302. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15833 (2021).

Rattanawiwatpong, P., Wanitphakdeedecha, R., Bumrungpert, A. & Maiprasert, M. Anti-aging and brightening effects of a topical treatment containing vitamin C, vitamin E, and raspberry leaf cell culture extract: A split-face, randomized controlled trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 19, 671–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13305 (2020).

Di Tano, M. & Longo, V. D. A fasting-mimicking diet and vitamin C: turning anti-aging strategies against cancer. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 7, 1791671. https://doi.org/10.1080/23723556.2020.1791671 (2020).

Rosas-Saavedra, C. et al. Putative Daucus carota Capsanthin-Capsorubin Synthase (DcCCS) possesses lycopene β-cyclase activity, boosts carotenoid levels, and increases salt tolerance in heterologous plants. Plants 15, 2788 (2023).

Tian, L. Genetically Modified Organisms in Food (ed. Ross Watson, R.& Preedy, V.R.) 353–360. (Academic Press, 2016).

Cunningham, F. X. Jr., Sun, Z., Chamovitz, D., Hirschberg, J. & Gantt, E. Molecular structure and enzymatic function of lycopene cyclase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp strain PCC7942. Plant Cell 6, 1107–1121. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.6.8.1107 (1994).

Tuan, P. A. et al. Efects of white, blue, and red light-emitting diodes on carotenoid biosynthetic gene expression levels and carotenoid accumulation in sprouts of tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.). J Agric Food Chem. 61, 12356–12361. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4039937 (2013).

Ezquerro, M., Burbano-Erazo, E. & Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. Overlapping and specialized roles of tomato phytoene synthases in carotenoid and abscisic acid production. Plant Physiol. 193, 2021–2036 (2023).

Lee, W. L., Huang, J. Z., Chen, L. C., Tsai, C. C. & Chen, F. C. Developmental and LED light source modulation of carotenogenic gene expression in Oncidium gower ramsey flowers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31, 1433–1445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-013-0617-9 (2013).

Fantini, E., Falcone, G., Frusciante, S., Giliberto, L. & Giuliano, G. Dissection of tomato lycopene biosynthesis through virus-induced gene silencing. Plant Physiol. 163, 986–998 (2013).

Loi, M., Villani, A., Paciolla, F., Mulè, G. & Paciolla, C. Challenges and opportunities of light-emitting diode (LED) as key to modulate antioxidant compounds in plants. A review. Antioxidants 10(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10010042 (2021).

Paciolla, C. et al. Vitamin C in plants: From functions to biofortification. Antioxidants 8, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8110519 (2019).

Lix, X. et al. Lycopene is enriched in tomato fruit by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00559 (2018).

Massot, C., Génard, M., Stevens, R. & Gautier, H. Fluctuations in sugar content are not determinant in explaining variations in vitamin C in tomato fruit. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.06.001 (2010).

Massot, C., Stevens, R., Génard, M., Longuenesse, J. J. & Gautier, H. Light affects ascorbate content and ascorbate-related gene expression in tomato leaves more than in fruits. Planta 235, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-011-1493-x (2012).

You, Y. & van Kan, J. A. Bitter and sweet make tomato hard to (b) eat. New Phytol. 230, 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17104 (2021).

Schwahn, K., de Souza, L. P., Fernie, A. R. & Tohge, T. Metabolomics-assisted refinement of the pathways of steroidal glycoalkaloid biosynthesis in the tomato clade. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 864–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12274 (2014).

Milner, S. E. et al. Bioactivities of glycoalkaloids and their aglycones from Solanum species. J. Agr. Food Chem. 59, 3454–3484. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf200439q (2011).

Roddick, J. G. Steroidal glycoalkaloids: Nature and consequences of bioactivity. In saponins Used in Traditional and Modern Medicine (eds Waller, G. R. & Yamasaki, K.) 277–295 (Springer, 1996).

Liu, Y., Hu, H., Yang, R., Zhu, Z. & Cheng, K. Current advances in the biosynthesis, metabolism, and transcriptional regulation of α-Tomatine in tomato. Plants 12, 3289 (2023).

Friedman, M. Tomato glycoalkaloids: Role in the plant and in the diet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50, 5751–5780. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf020560c (2002).

Li, Q. H. & Yang, H. Q. Cryptochrome signaling in plants. Photochem. Photobiol. 83, 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1562/2006-02-28-IR-826 (2007).

Lopez, L. et al. Tomato plants overexpressing cryptochrome 2 reveal altered expression of energy and stress-related gene products in response to diurnal cues. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 994–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02467.x (2012).

Folta, K. M. & Maruhnich, S. A. Green light: A signal to slow down or stop. J Exp Bot. 58, 3099–3111. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erm130 (2007).

Giliberto, L. Manipulation of the blue light photoreceptor cryptochrome 2 in tomato affects vegetative development, flowering time, and fruit antioxidant content. Plant. Physiol. 137, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.104.051987 (2005).

Molinero-Rosales, N., Latorre, A., Jamilena, M. & Lozano, R. SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS regulates the transition and maintenance of flowering in tomato. Planta 218, 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-003-1109-1 (2004).

Kerr, E. A. Single flower truss ‘“sft”’ appears to be on chromosome 3. Rep. Tom. Gen. Coop. 32, 31 (1982).

Song, J. et al. Variations in both FTL1 and SP5G, two tomato FT paralogs, control day-neutral flowering. Mol. Plant 13, 939–942 (2020).

Rajendran, S. et al. Optimization of tomato productivity using flowering time variants. Agronomy 11, 285 (2021).

Shalit, A. et al. The flowering hormone florigen functions as a general systemic regulator of growth and termination. PNAS 106, 8392–8397 (2009).

Périlleux, C. & Huerga-Fernández, S. Reflections on the triptych of meristems that build flowering branches in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 798502 (2022).

Lifschitz, E., Ayre, B. G. & Eshed, Y. Florigen and anti-florigen: A systemic mechanism for coordinating growth and termination in flowering plants. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 465 (2014).

Lifschitz, E. et al. The tomato FT ortholog triggers systemic signals that regulate growth and flowering and substitute for diverse environmental stimuli. PNAS 103, 6398–6403 (2006).

Park, W. T. Influence of light-emitting diodes on phenylpropanoid biosynthetic gene expression and phenylpropanoid accumulation in Agastache rugosa. Appl. Biol. Chem. 63, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-020-00510-4 (2020).

Funding

This study was jointly supported by Golnoor Company in Isfahan, Iran, and Dasht-e Naz Agricultural CO. in Sari, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Z. and MR.S. conceived the study and performed the analyses. N.Z., MR.S., M.T., and B.E.S.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, while M.S. participated in setting up and monitoring the lighting system throughout the year, and also provided light data analysis. All authors were involved in reading and approving the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Masoud Soleimani is affiliated with Golnoor Company, the LED light manufacturer involved in this study. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziaei, N., Talebi, M., Sayed Tabatabaei, B.E. et al. Intra-canopy LED lighting outperformed top LED lighting in improving tomato yield and expression of the genes responsible for lycopene, phytoene and vitamin C synthesis. Sci Rep 14, 19043 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69210-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69210-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multi-objective optimization identifies cultivation strategies for balancing yield, quality, and resource efficiency in hydroponic netted melon

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Effects of spatial setting of LED light source on yield, quality, and water-use efficiency in greenhouse tomato

BMC Plant Biology (2025)