Abstract

Digital watermarking of images is an essential method for copyright protection and image security. This paper presents an innovative, robust watermarking system for color images based on moment and wavelet transformations, algebraic decompositions, and chaotic systems. First, we extended classical Charlier moments to quaternary Charlier moments (QCM) using quaternion algebra. This approach eliminates the need to decompose color images before applying the discrete wavelet transform (DWT), reducing the computational load. Next, we decompose the resulting DWT matrix using QR and singular value decomposition (SVD). To enhance the system's security and robustness, we introduce a modified version of Henon's 2D chaotic map. Finally, we integrate the arithmetic optimization algorithm to ensure dynamic and adaptive watermark insertion. Our experimental results demonstrate that our approach outperforms current color image watermarking methods in security, storage capacity, and resistance to various attacks, while maintaining a high level of invisibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, the security of multimedia data in all forms (images, videos, and audio) plays an important role in all domains, especially for military or medical domains that require a very high level of confidentiality. To prevent illicit acts such as hacking, falsification, or unauthorized use of sensitive information, major security concerns must be addressed1.

Images, as carriers of crucial information, are increasingly widespread and stored across networks. This expansion has drawn the attention of researchers to issues relating to their transmission and preservation. The fundamental solution is to encrypt or digitally watermark these images before transferring them2,3,4. This approach aims to ensure the confidentiality and security of images, prevent unauthorized alteration, and enable authentication of their source. It thus meets the need for data protection and image integrity verification in an ever-growing digital environment5. In this context, cryptography was the first proposal to secure the transfer of digital color images. Today, modern encryption algorithms, with very sensitive and long security keys, can ensure the confidentiality and security of images. However, once the image is decrypted, it is no longer protected and can be distributed or modified in an illegal way. Information hiding, and more specifically the insertion of hidden data in the images, can be an answer to this problem6,7,8. Indeed, the insertion of a watermark in an image allows us to authenticate it and to guarantee its integrity. In recent years, significant advances have been made in the field of digital watermarking applied to color images. Table 1 provides an overview of the research and work carried out in this specific field. This work shows a growing interest in the use of digital watermarking methods, particularly for color images, to guarantee the security, confidentiality, and authenticity of visual data. This development reflects the growing importance of copyright protection and image security in various fields of application, such as medicine and military security.

We can see that copyright protection with color images has become an increasingly pressing challenge in this day and age, given that many organizations' trademarks, logos, and information to be hidden are in color. In this context, it is worth mentioning that color watermarking has two advantages over grayscale watermarking: (i) It allows a greater amount of data to be hidden. (ii) It achieves a higher level of realism since color perception depends not only on brightness but also on chrominance9,10.

After conducting an exhaustive review of the relevant literature and highlighting digital watermarking methods, we concluded that one of the most significant obstacles facing researchers in the field of digital watermarking is the development of an algorithm that manages to effectively balance the various properties, including imperceptibility, capacity, robustness, and data security. In this publication, we present a hybrid approach that combines the principles of digital watermarking and encryption. Our watermarking method is essentially based on the use of QCM, DWT, SVD, QR, and modified Henon cards. This innovative approach combines these elements to ensure the security and robustness of the watermark while preserving its invisibility in color images. We will go into more detail on the various stages of this method and provide an assessment of its performance through in-depth simulations.

To explain our new watermarking system in depth, we start by extending classical Charlier Moments (CM) to the QCM using quaternion algebra. This extension allows us to holistically represent color images without having to decompose their three components (red, green and blue) and without losing any information. Next, the resulting matrix of QCMs is subjected to decomposition in the DWT. This approach allows us to avoid decomposing the host and watermark images into three distinct RGB planes, reducing both decomposition time and computational complexity. We then decompose the DWT-generated matrix using both QR and SVD transformations. It is important to note that these QR and SVD decompositions are particularly effective in detecting important image features, thus reducing the amount of information to be analyzed in the image. To enhance the security and reliability of our system, we introduce a modified version of Henon's 2D chaotic map, which we refer to in this paper as 2D-FrMHM. This modified version offers more parameters than the classical map, thus enhancing the overall safety of the system. Finally, to guarantee a dynamic and adaptive scaling factor when inserting the watermark, we use the Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA). This final step contributes to improving the overall robustness of our watermarking system.

Essential contributions

The main contributions of this research.

-

1.

Introduction of Quaternion Moments (QCM): This study introduces QCM as a novel representation for color images. QCM not only preserves image integrity but also reduces computational complexity significantly, marking a significant advancement in image representation.

-

2.

Modification of Chaotic System: The research presents a novel modification to a chaotic system, enhancing the system's security and expanding its parameterization possibilities. This modification represents a noteworthy advancement in chaotic system design.

-

3.

Integration of Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA): The incorporation of AOA facilitates dynamic and adaptive scaling factor selection, enhancing the flexibility and efficiency of the watermarking system.

-

4.

Development of Hybrid Watermarking Method with Color Image Encryption: A key contribution is the proposal of a hybrid method that combines watermarking and color image encryption. This approach addresses the dual requirements of copyright protection and medical information confidentiality, representing a significant advancement in image security techniques.

General structure

We structured the rest of this work as follows: in “Preliminaries”, we present the theoretical background of the research. We devote “Fast computation of discrete orthogonal quaternary Charlier moments” to the presentation of quaternion orthogonal discrete Charlier moments. In “Improved reversible watermarking scheme”, we will present the proposed scheme for watermarking color images. In “Simulations and findings”, we illustrate the simulation results. The last section concludes the work.

Preliminaries

In this section, we outline the QR, SVD and a modified version of the 2D-Henon map, referred to in the remainder of this article as (2D-FrMHM), which will be implemented in the new watermarking system to improve its overall performance.

QR decomposition

QR is a matrix factorization where a real matrix is represented as the result of multiplying an orthogonal matrix Q by an upper triangular matrix R (Eq. 1)19,20.

Note that the R-matrix contains more significant elements that represent most of the energy of the signal (image) after the transformation. Experimentation and analysis revealed that the larger element provides numerical stability to external disturbances. In information security and data hiding technologies, A-matrix decomposition has the potential to increase anti-attack performance19,20.

Singular value decomposition

SVD is an algebraic approach in which matrices are treated based on their eigenvectors. The singular vector of the matrix can be obtained by SVD, keeping the correlation of the rows or columns of the original matrix21. The SVD decomposition of a matrix A of size \(N \times N\) is given by Eq. (2) with U and V, two orthogonal matrices, and S a diagonal matrix.

The diagonal elements of S = \(\left\{ {\sigma_{1} ,\sigma_{2} ,\sigma_{3} ,...,\sigma_{r} ,\sigma_{r + 1} ,...,\sigma_{n} } \right\}\) are singular values of matrix A.

Modified chaotic system

Chaotic systems22 are one of the most common methods used to contribute to the field of information security23,24,25. Mathematically, the 2D fractional Henon map is defined by Eq. (4), with \((x,y) \in {\text{R}}^{{2}} ,\,\,(\alpha ,\gamma ) \in {\text{R}}^{2}\) and the fractional order \(\upsilon \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\)26.

The chaotic characteristic of the map represented in Eq. (4) undergoes a modification due to the amplification of numerical errors when calculating output values for high orders. This amplification arises from the presence of the non-elementary analytical function gamma, as shown in Table 2. This modification is highlighted using the following parameters \(\left[ {\alpha ,\beta ,x(0),y(0),\upsilon } \right] = \left[ {1.95,\,\,0.001,\,0.009,\,\,0,\,\,0.98} \right]\).

Next, we introduce a 2D-FrMHM that addresses instability issues during computation by substituting \(\frac{\Gamma (n - i + \upsilon )}{{\Gamma (n - i + 1)}}\) with \(e^{\ln (x)}\). Moreover, to improve the security level, we will increase the complexity of the map by adding two additional parameters \(\varphi_{1} ,\varphi_{2}\) that will extend the space of the security keys. Indeed, the 2D-FrMHM is defined by Eq. (5)27.

where \((x,y) \in {\text{R}}^{{2}} ,\,\,(\alpha ,\gamma ) \in {\text{R}}^{2}\) and \(\upsilon \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) are the fractional orders, and \(\left| {\cos (i)} \right|\) is the absolute value of \(\cos (i)\).

To assess and visually represent the performance and effectiveness of the modified Henon map, we generate plots of the \(x(n)\,{\text{and}}\,y(n)\) coordinates of the map and the corresponding phase space as functions of the iteration number "n", using the same parameter values employed in the traditional 2D Henon map \(\left( {\left[ {\alpha ,\beta ,x(0),y(0),\varphi_{1} ,\varphi_{2} ,\upsilon } \right] = \left[ {1.95,\,\,0.001,\,0.009,\,\,0,\,\,0.98} \right]} \right)\).

Figure 1c illustrates the 2D-FrMHM by individual points in space, creating a shape closely resembling a half-oval, while Fig. 1a,b plot the two \(x(n)\,{\text{and}}\,y(n)\) coordinates as a function of the number of iterations "n," showing that they remain stable whatever "n." While Fig. 1d–f represent the classic Henon instability for large sizes. These observations reinforce the idea that the modified system exhibits both chaotic behavior and remarkable stability, particularly for high values of "n". This suggests that our stabilization approach is effective in resolving the numerical instability problems typically encountered in calculations involving high values of "n". Importantly, this stability is crucial to ensure the reliability of our method for digitally watermarking color images, particularly when applied to large images or applications requiring high accuracy. As a result, our approach offers a robust solution for inserting digital watermarks into color images while maintaining a chaotic behavior desirable for system safety and robustness28,29.

Fast computation of Charlier polynomial (CP)

The CP is defined by Eq. (7), where "x" and "n" represent the variable and the CP order, while "a" is the control parameter.

Iterative computation of CP30, whether with respect to order n or the variable x, generates the numerical instability of these polynomials, as highlighted in Figs. 2 and 3. This instability results from the propagation of numerical errors and can present challenges when applying these methods to large images in the security domain. To overcome this limitation, researchers have adopted the Gram‒Schmidt Ortho-normalization Process (GSOP)31,32,33. However, this method is still limited by the computational time, which is characterized by exponential behavior with an increment of n. As an example, the elapsed time in seconds (s) using GSOP for the case where N = 100 is 0.2546 s and for N = 1000 is 4.7835e + 02 s. Using the recursive method or the GSOP method to figure out CP causes problems with stability and the time to figure out CP.

The fundamental idea for solving the problems of numerical instability associated with CP calculation lies in the adoption of an innovative and efficient algorithm34. This algorithm is designed to guarantee the stable calculation of CP values, which is essential for our method of digitally watermarking color images. Its efficiency is based on two key principles: the notion of symmetry and the simultaneous use of standard recurrence relations associated with n and x. By adopting this method, our digital watermarking system for color images can effectively exploit the advantages of CP while avoiding the problems of numerical instability. This enhances the reliability and robustness of our approach, making it suitable for a wide range of applications, including the digital watermarking of large color images in fields requiring high precision and enhanced security35,36. It is important to note that this approach has already been successfully employed to stabilize other polynomials in previous works in the literature35.

Practically, after specifying the surface of CP calculations by determining the exact value of n, the plane of CP is divided into two parts having the shape of a triangle bounded by the diagonal n = x, as shown in Fig. 4. Thus, the calculation of the values of CP is performed in five steps, as shown in the pseudocode below (Algorithm 1), where \(\omega_{CP} \left( x \right)\) and \(\rho_{CP} \left( n \right)\) are the weight function and the quadratic norm respectively:

Algorithm 1: Fast computation of CP values34.

Step 1: The values of \(\tilde{C}P_{0}^{a} \left( 0 \right)\) are computed using the following equation:

Step 2: The values of \(\tilde{C}P_{0}^{a} \left( x \right)\) within the range \(x = 1,2,3,4,5 \ldots ,N - 1\) are computed using the following equation:

Step 3: The values of \(\tilde{C}P_{1}^{a} \left( x \right)\) within the range \(x = 1,2,3,4,5, \ldots ,N - 1\) are computed using the following equation:

Step 4: The values of \(\tilde{C}P_{n}^{a} \left( n \right)\) within the range \(n = 2,3,4,5, \ldots ,N_{\max }\) and \(x = n, \ldots ,N - 1\) are computed using the following equation:

Step 5: The values of \(\tilde{C}P_{n}^{a} \left( n \right)\) within the range \(n = 0,1,2, \ldots ,N_{\max }\) and \(x = n, \ldots ,N_{\max }\) are computed using the following equation:

Fast computation of discrete orthogonal quaternary Charlier moments

The quaternion model is an example of a mathematical approach that could be used effectively for digital color image processing37, as it generalizes grayscale modelling (on \(R\) or \(C\)) and treats color images holistically as an individual quaternion without decomposition into three RGB planes38,39. The quaternion representation of a digital color image \(f(x\,,y)\) is defined as follows:

The QCM are calculated from Eq. (15), knowing that the CP are calculated by algorithm 1.

with \(\mu = \frac{ - (i + j + k)}{{\sqrt 3 }}\). Taking into consideration the definition of \(\mu\), Eq. (16) is simplified as follows:

The 2D moments (\({\rm M}_{nm}\)) of \(f(x,y)\) of size \(N \times N\) using CP are obtained by the following equation35,40,41:

Using Eq. (18) to calculate moments generates a considerable computational load, making the process intensive in terms of computing resources. Therefore, to overcome this computational complexity, we opted for an alternative matrix approach.

where \({\rm M},CP_{n}^{a1} ,CP_{m}^{a2} \,{\text{and}}\,F\) is the matrix form of \({\rm M}_{nm} ,\tilde{C}P_{n}^{a1} (x),\tilde{C}P_{m}^{a2} (y),{\text{and}}\,f(x,y)\).

Using Eq. (19), we obtain the simplified matrix version of QCM:

In this equation, \({\rm M}_{R}\), \({\rm M}_{G}\) and \({\rm M}_{B}\) represent Charlier's conventional discrete orthogonal moments for the red, green and blue channels, respectively. Equation (20) can be reformulated as the following formula:

After the calculation of the \(QCM_{nm} (f)\) moments, we present the inverse form of \(IQCM_{nm} (f)\) (reconstruction of the 2D signal).

Utilizing Eqs. (17) and (23), we can now demonstrate the reverse computation of \(QCM_{nm} (f)\).

To illustrate the benefits and interest of extending classical Charlier moments to QCM moments, we conducted a visual evaluation using an arbitrary method of color image reconstruction from an MRI image of size 1024 (this image is selected from the database42). Figure 5 shows the reconstruction of the MRI image using a Charlier control parameter a = 512 for various orders ranging from n = 80 to n = 1024. The results of this evaluation demonstrate that QCMs outperform classical Charlier moments. Furthermore, these results indicate that the QCMs do not exhibit any loss of information.

Having outlined the theoretical part of the paper, we will now present the digital watermarking scheme we have developed.

Improved reversible watermarking scheme

In this section, the QCM, DWT, QR, SVD and 2D-FrMHM are used to present a new improved reversible watermarking scheme. Figure 6 provides an overview of the proposed system (the images used in this figure are selected from database Ref.42).

Proposed watermark scheme for color images

This phase consists of several successive steps, which generate watermarked color images from the original images and watermarks. A detailed description is presented in Fig. 7 (the images used in this figure are selected from database Ref.42 and website Ref.43).

Watermark insertion process

Step 1: Calculate the moments of the input images using Eq. (24). This step eliminates the need to decompose the input images before applying DWT. This approach significantly reduces the computation time. In addition, the CP parameters a1 and a2 are used to increase the extent of the available security key space (KEY1).

Step 2: Decompose the image \(I_{H} (x,y)\) into \(LL_{Hk} ,\,\,LH_{Hk} ,\,\, \, HL_{Hk} {\text{ and }}HH_{Hk}\) by K-DWT, where \(k = \log_{2} \frac{M}{N}\).

Step 3: Decompose the resulting image \(LL_{HK}\) into two matrices \(Q_{H}\) and \(\,R_{H}\), as shown in Eq. (29), while considering the size of \(LL_{HK}\); \(\left( {\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}\,,\,\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}} \right)\).

Step 4: Decompose the matrix \(\,R_{H}\) into three matrices \(U_{H}\) , \(S_{H}\) and \(V_{H}\) based on SVD decomposition as shown in Eq. (30), while considering the size of \(S_{H}\)\(\left( {\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}\,,\,\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}} \right)\).

Step 5: Encrypt the \(S_{H}\) matrix using 2D-FrMHM. To enhance the security of the proposed digital watermarking system, we implemented two crucial steps:

-

(a)

Confusion process: In this step, we interchange the positions of the values within \(S_{H}\) to generate matrix \(S_{{H_{2} }}^{{}}\), which serves as the representation of the permuted \(S_{H1}\). To accomplish this, we use two chaotic sequences X(i) and Y(j) defined in Eq. (5) to generate the following two vectors.

$$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {X(i) = \left[ {x(1);x(2);x(3);......;x(M \times M)} \right]} \\ {Y(j) = \left[ {y(1);y(2);y(3);......;y(M \times M)} \right]} \\ \end{array} } \right. $$(28)

The two resulting vectors are arranged in ascending order and saved in variables denoted as \(X*(i){\text{ and }}Y*(j)\):

It is important to note that to guarantee the reversibility of the process, \(L_{x} \left( i \right){\text{ and }}L_{y} \left( j \right)\) must receive the index from which \(X*(i){\text{ and }}Y*(j)\) originated, for the change to be reversible. After completing the preparation of the chaotic sequences. We convert the matrix \(S_{H}\) into a 1D vector, then rearrange the elements of this vector according to \(L_{x} \left( i \right)\) to obtain the \(S_{{H_{1} }} = \left\{ {S_{{H_{1} }} (1)\,,\,S_{{H_{1} }} (2)\,,\,S_{{H_{1} }} (3)\,,....;\,S_{,} \left( {\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}\, \times \frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}} \right)} \right\}\) sequence. This sequence is transformed into a 2D matrix \(S_{{H_{1} }} = \left\{ {S_{{H_{1} }} (x,y)} \right\}_{x,y = 1}^{{x,y = \frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }},\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}}}\). This step is performed for the \(S_{{H_{1} }}\) matrix, using \(L_{y} \left( j \right)\) to make \(S_{{H_{2} }} = \left\{ {S_{{H_{2} }} (x,y)} \right\}_{x,y = 1}^{{x,y = \frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }},\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}}}\) (\(S_{{H_{1} }}\) scrambled).

-

(b)

Diffusion process: During this crucial stage of the process, the values of the \(S_{{H_{2} }}\) matrix undergo modifications to give rise to the encrypted matrix \(ES_{H}\). This process is orchestrated by the use of two chaotic sequences presented in Eq. (5)\(\left( {X(i){\text{ and }}Y(j)} \right)\), where they are rounded off to the nearest integer \(\left( {X_{1} (i) = floorX(i){\text{ and }}Y_{1} (j) = floorY(j)} \right)\).

The XOR function \(\left( \oplus \right)\) is used to combine the two sequences \(X_{1} (i) = \left[ {x_{1} (1),x_{1} (2),x_{1} (3),....,x_{1} \left( {\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }} \times \frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}} \right)} \right]\) and \(Y_{1} (i) = \left[ {Y_{1} (1),Y_{1} (2),Y_{1} (3),....,Y_{1} \left( {\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }} \times \frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}} \right)} \right]\), and the result is then resized to form a 2D matrix \(T = \left\{ {T(x,y)} \right\}_{x,y = 1}^{{x,y = \frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }},\frac{M}{{2^{k + 1} }}}}\).

Before proceeding to the step of inserting \(I_{W} (x,y)\) into \(I_{W} (x,y)\), it should be noted that the image \(I_{W} (x,y)\) of size \(N \times N\) goes through the same steps as the image \(I_{H} (x,y)\) cited before to obtain the matrix \(ES_{W}\). With the exception of step 1, we compute the QCMs of image \(I_{W} (x,y)\) using Eq. (24) up to order N, and in step 2, the image \(I_{W} (x,y)\) is subjected to a single decomposition \(1 - DWT\).

Step 6: Calculate the integrated singular value \(ES_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\) by using a scaling factor \(\theta\).

The final stage of the watermarking process involves the reconstruction of the watermarked image. This is a critical step to ensure that the watermark is correctly embedded in the image and can be reliably extracted later. The reconstruction process follows a series of carefully designed steps, as depicted in Fig. 6.

Watermark extraction process

The phase of watermark extraction uses the watermarked host image \(I_{{_{HW} }}^{{}} (x,y)\) of size \(M \times M\) as input as long as the extracted watermark \(I_{{_{W} }}^{ * } (x,y)\) of size \(N \times N\) is the output of this phase. This process is illustrated in Fig. 8. We describe the extraction process in the following sequence of steps (the images used in this Fig. 8 are selected from database Ref.42 and website Ref.43).

Step 1: Compute the MCQs of the input image using Eq. (13) up to order M for image \(I_{{_{HW} }}^{{}} (x,y)\)

Step 2: Use the \(k - DWT\) transformation to decompose the \(I_{{_{HW} }}^{{}} (x,y)\) image into four equals \(LL_{{_{HWk} }}^{{}} ,\,LH_{{_{HWk} }}^{{}} ,\, \, HL_{{_{HWk} }}^{{}} {\text{ and }}HH_{{_{HWk} }}^{{}}\) subbands.

Step 3: Use QR to decompose \(LL_{{_{HWk} }}^{{}}\) into \(Q_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\) and \(\,R_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\).

Step 4: Use SVD decomposition, to decompose \(\,R_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\) into three matrices \(U_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\), \(S_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\) and \(V_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\).

Step 5: Encrypt \(S_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\) using 2D-FrMHM to acquire the \(E\hat{S}_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\) matrix.

Step 6: Utilize the scaling factor \(\theta\) to compute the singular value \(E\hat{S}_{{_{HW} }}^{{}}\).

Step 7: Decrypt the \(E\hat{S}_{{_{W} }}^{{}}\) using 2D-FrMHM to obtain the \(\hat{S}_{{_{W} }}^{{}}\) matrix.

Step 8: Apply the inverse of the SVD transformation to obtain the matrix \(\,\hat{R}_{{_{w} }}^{{}}\).

Step 9: Apply inverse QR decomposition to recover the \(L\hat{L}_{{_{W1} }}^{{}}\) matrix, followed by the inverse operation of the DWT transformation.

Step 10: Apply the inverse operation of the QCM to reconstruct watermark \(I_{{_{W} }}^{ * } (x,y)\) with size \(N \times N\).

After presenting in detail the operation of the watermarking system, which generates color images incorporating watermarks from the original images and watermarks, the next section looks at the use of AOA optimization to discover the optimum scaling factor.

Scale factor optimization via AOA

Preliminaries of the AOA algorithm

The AOA algorithm is based on the four fundamental arithmetic operators (+ , –, x, and /). The optimization process of this algorithm has two key steps: an inspection phase and a manipulation phase. Figure 9 presents an overview of the two phases and their roles44,45.

In the following, we will give a more detailed overview of the AOA. First, we start with the initialization step, in which a set of candidate solutions is randomly created \(X = \left[ {x_{1,1} \,;\,\,x_{2,1} \,;....;\,\,x_{N,n} \,} \right]\). In addition, Eq. (34) is chosen to play the accelerating function.

Before starting the work process, the AOA must determine the search phase, either inspection or manipulation. The Math Optimizer Accelerated (MOA) function represents a coefficient calculated according to Eq. (33), which is then used in the search stages. Where \(C_{iter}\) and \(M_{iter}\) denote the current iteration and the maximum number of iterations.

The inspection phase within AOA involves multiple convergent iterations aimed at thoroughly exploring the entire search space to ensure broad coverage. To prevent convergence into local solutions, AOA leverages arithmetic operators (refer to Eq. 37) in conjunction with the optimization probability function (MOP) (see Eq. 35)45.

where \(\varepsilon\), \(\mu\) and MOP denote an integer, the control parameter for adjusting the search process and the function of the optimization probability, respectively.

During the manipulation phase, AOA enables precise convergence to attain an enhanced solution following the inspection phase. This phase primarily relies on arithmetic operators, specifically subtraction (-) and addition ( +), as defined in Eq. (36), in combination with the MOP as described in Eq. (35)45.

Scale factor optimization

The watermark insertion and extraction process consists of several successive steps: calculation of the QCMs of the input color image, application of the discrete wavelet transform, QR decomposition, SVD decomposition and encryption via 2D-FrMHM. These steps are used to generate watermarked color images, as illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8. This process is highly dependent on a scaling factor. To find a suitable factor, we propose to use an efficient optimization algorithm. This optimization algorithm is inserted after step 6, which involves calculating the integrated singular value, as described in “Proposed watermark scheme for color images” of the proposed watermarking scheme for color images (Fig. 10).

It should be noted that the scaling factor \(\theta\) presented in “Improved reversible watermarking scheme”, more precisely Eq. (31), varies according to the host image \(I_{H} (x,y)\) and watermark \(I_{W} (x,y)\), meaning that different watermarks require different scaling factors, even if they are all embedded in the same host image. This paper opts for the use of AOA to improve the reliability and robustness of our new system. The proposed process for selecting optimal values of the scaling factor using AOA aims to solve the challenge of the trade-off between invisibility and robustness. This algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 2. In addition, standard performance metrics such as PSNR, NC, and SSIM are also employed to assess the visibility and reliability of the proposed system.

We apply these steps to develop an objective function, which we will henceforth refer to as \(FO_{\theta }^{opt}\). This function will serve as the basis for our subsequent work.

where \(\sigma_{{I_{H} }}^{2} \,{\text{and}}\,\sigma_{{I_{H}^{ * } }}^{2}\) are the variances of \(I_{H}\) and \(I_{H}^{ * }\). \( \sigma _{{I_{{H_{{I_{H}^{*} }} }} }} \) is the covariance of \(I_{H}\) and \(I_{H}^{ * }\). \(d_{1}\) and \(d_{2}\) are two variables that are used to stabilize the division with a low denominator, and \(FO_{\theta }^{opt}\) is defined to optimize the scaling factor, which is given by the following equation.

By applying the formula (PSNR/λ), the PSNR undergoes a normalization that takes into account the weighting factor λ. Typical PSNR values are in the range of 1 to 70 dB. Therefore, if the PSNR/λ ratio is equal to or greater than 1, this indicates that the watermark is sufficiently discrete to be deemed acceptable. On the other hand, if this ratio is less than 1, the watermark is detectable and therefore considered unacceptable.

Algorithm 2 summarizes the idea of optimizing the scaling factor \(\theta\) by seeking to maximize the objective function \(FO_{\theta }^{opti}\). This step is based on the AOA algorithm: First, we select the host \(I_{H} (x,y)\) image and watermark \(I_{W} (x,y)\), taking into account the initial parameters of the AOA algorithm and the \(FO_{\theta }^{opti}\). Next, the algorithm randomly generates a set of initial solutions. These solutions are evaluated using the \(FO_{\theta }^{opti}\). Next, the algorithm updates the scaling factor \(\theta\) using the exploration and exploitation phases of the AOA algorithm, and we evaluate the value of the \(FO_{\theta }^{opti}\). This step is repeated iteratively until the maximum number of iterations is reached (\(M_{iter}\)). Finally, the output of this optimization generates the optimal values of the scaling factor \(\theta_{opt}\) and the watermarked image \(I_{H}^{ * }\).

Algorithm 2: Scale factor optimization steps.

Simulations and findings

In this section, we evaluated the efficiency of the proposed watermarking method, which is based on quaternion moments, wavelet transforms, algebraic decompositions, and the modified Henon map. To enhance clarity, this section is divided into three subsections.

-

The first subsection focuses on evaluating the robustness of the encryption with the modified Henon map. It includes an in-depth security analysis, a detailed histogram study, a correlation investigation as well as an entropy analysis.

-

The second subsection examines the performance of the proposed digital watermarking system. This part of the analysis covers the impact of the choice of scale factor and carries out a careful analysis of the invisibility and robustness of digital watermarking.

-

The third subsection provides a detailed comparison with similar works. This comparison highlights key differences between our approach and existing approaches, as well as the specific advantages of our method.

Additionally, we consider NC along with SSIM and PSNR to evaluate the robustness aspect of this innovative watermarking scheme. A summary of these and other metrics can be found in Fig. 11 for reference1,2,46,47,48,49.

Encryption process using 2D-FrMHM

Security analysis

The security key (KEY) produced by 2D-FrMHM is formed by the concatenation of the keys generated in step 5 of the watermark insertion process \(KEY = \left\{ {\alpha ,\beta ,x(0),y(0),x^{ * } (0),y^{ * } (0),\varphi_{1} ,\varphi_{2} ,\varphi_{3} ,\varphi_{4} ,\upsilon } \right\}\).

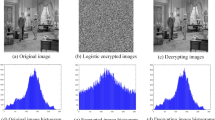

The following scenario aims to evaluate key sensitivity in the following steps: Firstly, the original image shown in Fig. 12a undergoes an encryption process using the "KEY" security key, thereby generating the encrypted RGB image42 shown in Fig. 12b. Figure 12c depicts the image decrypted by the correct key. Next, the "KEY" security key undergoes a minor modification, equivalent to a change in order by \(10^{ - 15}\), thus becoming "KEY*." The original encrypted image is then decrypted using the modified "KEY*" key. The conclusions of this evaluation reveal that the proposed system is highly sensitive to variations in the security key, particularly evident in PSNR values that do not exceed 10 dB, as illustrated in Fig. 12d.

Histogram analysis

Optimal encryption should generate encrypted images with as uniform a histogram as possible50. As illustrated in Fig. 13, the histograms of the three channels of the encrypted image42 (R, G and B) show a horizontal distribution. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed 2D-FrMHM in terms of resistance to statistical attacks.

Correlation and entropy analysis

Correlation analysis is a well-established approach to evaluating the relationships between pixels in an image51. It quantifies the statistical dependence between the brightness or color values of different pixels. This analysis is crucial in various fields, including computer vision, image processing and statistics. To measure the correlation between each pair of pixels, we use the following formula23.

when

Using point maps to visually represent the correlation between pixels before and after encryption is an effective way of assessing the impact of the encryption process on the image. This method makes it possible to highlight changes in the spatial distribution of pixel values and determine whether encryption has succeeded in disrupting the correlation between pixels in the original image. Specifically, in Fig. 14, the dot maps show the correlation coefficients between adjacent pixels in the three-color channels (R, G, and B) of the image. Prior to encryption, when the image is still unaltered, neighboring pixels can be expected to show strong correlation, resulting in coherent patterns on the dot maps.

To reinforce this observation, we proceeded to calculate the correlation coefficients on another 512 × 512-pixel medical image42 using different chaotic maps reported in previous work (see Table 3). This comparative analysis highlights that the correlation coefficients associated with the encrypted osteochondroma image tend towards zero, indicating extremely low correlation.

The entropy analysis, as presented in Table 4, highlighted that all three channels of the encrypted image (Red, Green and Blue) exhibit information entropy very close to the theoretical maximum value of 8. These results conclusively confirm that the 2D-FrMHM model is highly effective in defending against attacks that attempt to take advantage of the information entropy present in the image. This observation is of great importance, as it demonstrates the robustness of the 2D-FrMHM model in the face of attack attempts specifically aimed at disrupting the entropy of information within the image. Entropy, being a crucial indicator of data complexity and disorganization, would play a key role in preserving the security and confidentiality of encrypted images.

Image watermark

Effects of the choice of the scaling factor

To assess the influence of the scale factor on the process of incorporating and extracting color watermarks, we used two separate images. The first comes from the database "The Visible Human Project" and has a resolution of 512 × 51242. The second represents the logo of the Hassan II Hospital in Fez43 and has a resolution of 128 × 128, as shown in Fig. 15. The incorporation and extraction phases reveal that the scaling factor, denoted \(\theta\), exerts a significant influence on the quality of the filtered image as well as on the extracted watermark. In this experiment, we systematically modified the value of \(\theta\), ranging from 0.01 to 1. The optimum value is the one that achieves the best balance between imperceptibility and robustness. It is important to note that the choice of scale factor depends on both the host image \(\left( {I_{H} (x,y)} \right)\) and the watermark \(\left( {I_{W} (x,y)} \right)\) used. Consequently, different watermark images require different scaling factors, even if they are inserted in the same host image.

In light of these results, we chose to adopt the AOA algorithm45 in conjunction with the objective function \(\left( {FO_{\theta }^{opt} } \right)\) to solve the \(\theta\) parameter challenge. Table 5 provides a comparison with other algorithms, including particle swarm optimization58 (PSO), gray wolf optimization59 (GWO), and artificial bee colony optimization60 (ABC). Performance, assessed using standard metrics such as PSNR, NC, and SSIM, testifies to the superiority of our algorithm. Note that the four selected algorithms adopt a maximum iteration of 200. This means that each algorithm has a fixed limit of 200 execution cycles to attempt to reach an optimal solution. To ensure reliable results, each algorithm is run independently 15 times. This minimizes the effect of random variation and provides a representative average of each algorithm's performance. The results recorded during these multiple runs are then compiled and presented in Table 5.

Invisibility and robustness analysis

In this evaluation, we examined how the size of the color watermark affects the embedding and extraction steps61. To illustrate this process, Fig. 16 shows watermarked host images, together with the corresponding extracted watermarks42, with dimensions of 256 × 256 and 128 × 128 pixels (the images used in this Fig. 16 are selected from database Ref.42 and website Ref.43).

To carry out this evaluation, this section highlights a real 512 × 512 pixel medical image42. As can be seen in Fig. 16, the proposed digital watermarking system achieved its objectives, with results clearly defined by PSNR values above 70.00 and SSIM values above 0.99. The NC of the extracted watermarks all shows a value of 1.0000 (no alterations were made to the watermarked host images). This indicates the excellent visibility of the watermarking method. In summary, the proposed watermarking scheme can satisfy the prerequisites for invisible watermarks. In addition, the use of a watermark of size 128 × 128 produces superior results to those obtained by using a watermark of size 256 × 256.

To assess the robustness of the proposed watermarking system, first, as shown in Fig. 17, we subjected photographs that were previously watermarked with color watermarks of sizes 128 × 128 and 256 × 256 to various attacks (see Table 6). Next, we extracted the watermark and calculated the normalization coefficient (NC) values.

Figure 18 is an important illustration of the robustness of the watermarking system we developed. It shows the watermarks that we were able to recover after subjecting the watermarked images to various filtering attacks, such as scaling, applying filters, adding noise, and other similar attacks. We carried out these tests on two sets of watermarks, one of size 128 × 128 pixels and the other of size 256 × 256 pixels. Table 7 contains the PSNR, NC and SSIM measurements which provide a comprehensive assessment of the quality and fidelity, whether of the watermarked image compared to the original or of the watermark before its insertion and after its extraction. To maintain consistency with Eq. (41), which defines the objective function, we assigned the PSNR and SSIM measurements to the watermarked images, while the NC is used to evaluate the watermark. The results shown in Table 7 indicate that our watermarking system is able to recover watermarks reliably even after being subjected to filtering attacks. This confirms the robustness of the system, essential to guarantee the security and integrity of watermarks in real-world conditions where images may be exposed to different types of alterations.

In summary, the use of a variety of watermarks has emphasized the robustness of our digital watermark. After performing several attacks on the watermarked image and determining the NC value of each attack using two watermarks, the first of size 128 × 128 and the second of size 256 × 256. Figure 19 illustrates how the average NC value varied depending on the attack used, including the filter attack, noise attack, compression attack, scaling attack, and sharpening attack. The red curve represents this variation when using a 256 × 256 size watermark, while the blue curve illustrates this variation when using a 128 × 128 size watermark. The results shown in this figure show that, when a small watermark is used, our method works well.

Table 8 shows a comparative study of the robustness of our method with other works that are based on metaheuristic algorithms, including an ABC-based watermark, a PSO-GWO based watermark, and an ABC-based watermark. From the results shown in Table 8, we can see that the proposed method provides a high NC compared to the other methods under the different attacks. It is important to note that the attack parameters we examined earlier were static, i.e., fixed and pre-set. However, to get a more complete and realistic view of the robustness of our watermarking system, it is also essential to take into account dynamic parameters, which can vary depending on the situation or environment.

In order to better understand the impact of dynamic parameter choices when applying attacks, we conducted tests taking these parameter variations into consideration. The results of these tests are shown in Fig. 20. This approach enables us to demonstrate the ability of our system to maintain its robustness even when attack parameters vary.

Comparison with similar work and discussion of results

To guarantee the credibility and validity of our results, we have undertaken an essential step to validate and authenticate our method. In this subsection, our system, based on a combination of DWT, QR, SVD, and the 2D-Henon map, is subjected to a detailed comparison with several other related methods. This comparison is based on a set of crucial features, as shown in Table 9. In this comparative analysis, we take into account a series of important properties, each of which has a significant impact on overall performance.

As the table clearly illustrates, our proposed approach proves extremely effective in comparison with other methods based on standard metrics64,65. These remarkable results can be attributed to several key factors that distinguish our approach. Firstly, the use of discrete orthogonal moments in their quaternion form. QCMs are particularly effective for representing images with low information redundancy, while preserving the visual quality of the images used in the proposed watermarking system. What's more, our system benefits from scale factor optimization via the AOA optimization algorithm, which guaranteed precise scale factor adjustment for each specific host image and watermark. By combining these two elements—the use of QCM and scale factor optimization via AOA—our system offers superior performance in terms of image quality and watermark detection capability. Thanks to this combination of techniques, we are able to achieve outstanding results, reinforcing the effectiveness and reliability of our watermarking method.

Conclusion

In this work, we introduced a novel watermarking system designed to guarantee the robust integrity of color images. Our method is founded on the use of moment and wavelet transformations, algebraic decompositions, and chaotic systems. As a first step, we have extended the scope of classical Charlier moments by adapting them to QCM through the exploitation of quaternion algebra. This first phase of our system enabled us to perform the DWT without requiring color image decomposition while minimizing the computational load at each stage of the process. Subsequently, we performed a decomposition of the resulting matrix generated by the DWT using QR decomposition and SVD. Then, to enhance the safety and robustness of our system, we used a modified version of Henon's 2D chaotic map, characterized by extended parameters compared to the classical version. Finally, to optimize watermark insertion, we employed the arithmetic optimization algorithm, enabling dynamic and adaptive estimation of the scaling factor. This overall approach is designed to guarantee the security, reliability, and capacity of our watermarking system while maintaining the excellent invisibility of watermarks inserted in color images. Experimental results show that our approach outperforms recent color image processing methods in terms of security, storage capacity, and resistance to various attacks while maintaining high invisibility. In the future, we intend to put our watermarking system into practice using programmable electronic boards such as Arduino and Raspberry Pi. This is intended to overcome the limitations of our current system, notably the high computation time involved in using a meta-heuristic.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Loan, N. A. et al. Secure and robust digital image watermarking using coefficient differencing and chaotic encryption. IEEE Access. 6, 19876–19897. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2808172 (2018).

Mali, S. D. & Agilandeeswari, L. Non-redundant shift-invariant complex wavelet transform and fractional gorilla troops optimization-based deep convolutional neural network for video watermarking. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 35(8), 101688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101688 (2023).

Wu, D. et al. Robust zero-watermarking scheme using DT CWT and improved differential entropy for color medical images. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101708 (2023).

Fragoso-Navarro, E., Rangel-Espinoza, K., Nakano-Miyatake, M., Cedillo-Hernandez, M. & Perez-Meana, H. Seam Carving based visible watermarking robust to removal attacks. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(7), 4499–4513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.03.010 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. A novel robust color image watermarking method using RGB correlations. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78(14), 20133–20155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-7326-9 (2019).

Bideh, P. N., Mahdavi, M., Borujeni, S. E. & Arasteh, S. Security analysis of a key based color image watermarking vs. a non-key based technique in telemedicine applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 77(24), 31713–31735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-6218-8 (2018).

Darwish, S. M. & Al-Khafaji, L. D. S. Dual watermarking for color images: A new image copyright protection model based on the fusion of successive and segmented watermarking. Multimed. Tools Appl. 79(9–10), 6503–6530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-08290-w (2020).

Duan, S., Wang, H., Liu, Y., Huang, L. & Zhou, X. A novel comprehensive watermarking scheme for color images. Secur. Commun. Netw. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8840779 (2020).

Begum, M., Ferdush, J. & Uddin, M. S. A hybrid robust watermarking system based on discrete cosine transform, discrete wavelet transform, and singular value decomposition. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(8), 5856–5867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.07.012 (2022).

Prabha, K. & Shatheesh, S. I. An effective robust and imperceptible blind color image watermarking using WHT. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(6), 2982–2992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.04.003 (2022).

Zhang, X., Su, Q., Yuan, Z. & Liu, D. An efficient blind color image watermarking algorithm in spatial domain combining discrete Fourier transform. Optik (Stuttg). 219(July), 165272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.165272 (2020).

Li, J., Yu, C., Gupta, B. B. & Ren, X. Color image watermarking scheme based on quaternion Hadamard transform and Schur decomposition. Multimed. Tools Appl. 77(4), 4545–4561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4452-0 (2018).

Abdulrahman, A. K. & Ozturk, S. A novel hybrid DCT and DWT based robust watermarking algorithm for color images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78(12), 17027–17049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-7085-z (2019).

Sharma, S., Sharma, H. & Sharma, J. B. An adaptive color image watermarking using RDWT-SVD and artificial bee colony based quality metric strength factor optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 84, 105696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105696 (2019).

Liu, X. L., Lin, C. C. & Yuan, S. M. Blind dual watermarking for color images’ authentication and copyright protection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 28(5), 1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2016.2633878 (2018).

Zhou, X., Ma, Y., Zhang, Q., Mohammed, M. A. & Damaševičius, R. A reversible watermarking system for medical color images: Balancing capacity, imperceptibility, and robustness. Electron. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10091024 (2021).

Liu, D., Su, Q., Yuan, Z. & Zhang, X. A color watermarking scheme in frequency domain based on quaternary coding. Vis. Comput. 37(8), 2355–2368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-020-01991-6 (2021).

Liu, D., Su, Q., Yuan, Z. & Zhang, X. A blind color digital image watermarking method based on image correction and eigenvalue decomposition. Signal Process. Image Commun. 95(April), 116292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.image.2021.116292 (2021).

Su, Q., Niu, Y., Wang, G., Jia, S. & Yue, J. Color image blind watermarking scheme based on QR decomposition. Signal Process. 94(1), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sigpro.2013.06.025 (2014).

Nejati, F., Sajedi, H. & Zohourian, A. Fragile watermarking based on QR decomposition and fourier transform. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 122(1), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-021-08895-1 (2022).

Sivananthamaitrey, P. & Kumar, P. R. Optimal dual watermarking of color images with SWT and SVD through genetic algorithm. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 41(1), 224–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-021-01773-y (2022).

Yan, M., Jie, J. & Zhang, P. Chaotic systems with variable indexs for image encryption application. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 19585 (2022).

Kaur, M. & Kumar, V. A comprehensive review on image encryption techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 27(1), 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-018-9298-8 (2020).

Muñoz-Guillermo, M. Image encryption using q-deformed logistic map. Inf. Sci. (NY). 552, 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.11.045 (2021).

Qian, X. et al. A novel color image encryption algorithm based on three-dimensional chaotic maps and reconstruction techniques. IEEE Access. 9, 61334–61345. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3073514 (2021).

Hu, T. Discrete chaos in fractional henon map. Appl. Math. 05(15), 2243–2248. https://doi.org/10.4236/am.2014.515218 (2014).

Tahiri, M. A. et al. New color image encryption using hybrid optimization algorithm and Krawtchouk fractional transformations. Vis. Comput. 39(12), 6395–6420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-022-02736-3 (2023).

Bencherqui, A. et al. Chaos-enhanced archimede algorithm for global optimization of real-world engineering problems and signal feature extraction. Processes 12(2), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12020406 (2024).

Bencherqui, A. et al. Optimal algorithm for color medical encryption and compression images based on DNA coding and a hyperchaotic system in the moments. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 50, 101612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2023.101612 (2024).

Hmimid, A. & Sayyouri, M. H. Image classification using novel set of charlier moment invariants. WSEAS Trans. Signal Process. 10(1), 156–167 (2014).

Camacho-Bello, C. & Rivera-Lopez, J. S. Some computational aspects of Tchebichef moments for higher orders. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 112, 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2018.08.020 (2018).

Tahiri, M. A. et al. Octonion-based transform moments for innovative stereo image classification with deep learning. Complex Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-023-01337-4 (2024).

Karmouni, H. et al. Secure and optimized satellite image sharing based on chaotic eπ map and Racah moments. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121247 (2024).

Abdul-Hadi, A. M., Abdulhussain, S. H. & Mahmmod, B. M. On the computational aspects of Charlier polynomials. Cogent Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2020.1763553 (2020).

Karmouni, H., Jahid, T., Sayyouri, M., Hmimid, A. & Qjidaa, H. Fast reconstruction of 3D images using Charlier discrete orthogonal moments. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 38(8), 3715–3742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-019-01025-0 (2019).

Tahiri, M. A., Karmouni, H., Sayyouri, M., Qjidaa, H. 2D and 3D Image Localization, Compression and Reconstruction Using New Hybrid Moments (Springer US, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11045-021-00810-y.

Yamni, M., Karmouni, H., Sayyouri, M., Qjidaa, H. & Flusser, J. Novel Octonion Moments for color stereo image analysis. Digit. Signal Process. A Rev. J. 108, 102878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsp.2020.102878 (2021).

Amakdouf, H., Zouhri, A., Mallahi, E. L. & M, Qjidaa H.,. Color image analysis of quaternion discrete radial Krawtchouk moments. Multimed. Tools Appl. Publ. Online https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-09120-0 (2020).

Dubey, V. Quaternion Fourier transform for colour images. IJCSIT 5(3), 4411–4416 (2014).

Sayyouri, M., Hmimid, A. & Qjidaa, H. Image analysis using separable discrete moments of Charlier-Hahn. Multimed. Tools Appl. 75(1), 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-014-2307-5 (2016).

Hmimid, A., Sayyouri, M. & Qjidaa, H. Image classification using separable invariant moments of Charlier-Meixner and support vector machine. Multimed. Tools Appl. 77(18), 23607–23631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-5623-3 (2018).

National Library of Medicine—National Institutes of Health. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed 18 Jan 2021).

Hassan II University Hospital. http://www.chu-fes.ma/logo_chu-final/.

Premkumar, M. et al. A new arithmetic optimization algorithm for solving real-world multiobjective CEC-2021 constrained optimization problems: Diversity analysis and validations. IEEE Access. 9, 84263–84295. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3085529 (2021).

Abualigah, L., Diabat, A., Mirjalili, S., Abd Elaziz, M. & Gandomi, A. H. The arithmetic optimization algorithm. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2020.113609 (2021).

Zhou, N. R., Hu, L. L., Huang, Z. W., Wang, M. M. & Luo, G. S. Novel multiple color images encryption and decryption scheme based on a bit-level extension algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122052 (2024).

Gong, L. H. & Luo, H. X. Dual color images watermarking scheme with geometric correction based on quaternion FrOOFMMs and LS-SVR. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023(167), 109665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.109665 (2023).

Xiaohui, Z. Text information hiding and recovery via wavelet digital watermarking method. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9532. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36759-0 (2021).

Kowalczuk, Y. & Holub, J. Evaluation of digital watermarking on subjective speech quality. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 20185. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99811-x (2021).

Hua, Z., Zhu, Z., Yi, S., Zhang, Z. & Huang, H. Cross-plane colour image encryption using a two-dimensional logistic tent modular map. Inf. Sci. (NY). 546, 1063–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.09.032 (2021).

Aminuddin, A. & Ernawan, F. AuSR1: Authentication and self-recovery using a new image inpainting technique with LSB shifting in fragile image watermarking. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(8), 5822–5840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2022.02.009 (2022).

Hu, X., Wei, L., Chen, W., Chen, Q. & Guo, Y. Color image encryption algorithm based on dynamic chaos and matrix convolution. IEEE Access. 8, 12452–12466. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2965740 (2020).

Xu, L., Gou, X., Li, Z. & Li, J. A novel chaotic image encryption algorithm using block scrambling and dynamic index based diffusion. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2017(91), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2016.10.012 (2016).

Kumar, V. & Girdhar, A. A 2D logistic map and Lorenz-Rossler chaotic system based RGB image encryption approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80(3), 3749–3773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-09854-x (2021).

Rehman, A. U., Khan, J. S., Ahmad, J. & Hwang, S. O. A new image encryption scheme based on dynamic S-boxes and chaotic maps. 3D Res. 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13319-016-0084-9 (2016).

Qayyum, A. et al. Chaos-based confusion and diffusion of image pixels using dynamic substitution. IEEE Access. 8, 140876–140895. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3012912 (2020).

Ahmad, J. & Hwang, S. O. Chaos-based diffusion for highly autocorrelated data in encryption algorithms. Nonlinear Dyn. 82(4), 1839–1850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-015-2281-0 (2015).

Li, Y., Lin, X. & Liu, J. An improved gray wolf optimization algorithm to solve engineering problems. Sustainability 13(6), 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063208 (2021).

Hou, Y. et al. Improved grey wolf optimization algorithm and application. Sensors 22(10), 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22103810 (2022).

Garro, B. A., Rodríguez, K. & Et Vázquez, R. A. Classification of DNA microarrays using artificial neural networks and ABC algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 38, 548–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.10.002 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. An optimized image watermarking method based on HD and SVD in DWT domain. IEEE Access. 7, 80849–80860. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2915596 (2019).

Shen, Y., Tang, C., Xu, M., Chen, M. & Lei, Z. A DWT-SVD based adaptive color multi-watermarking scheme for copyright protection using AMEF and PSO-GWO. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021(168), 114414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114414 (2020).

Ansari, I. A., Pant, M. & Ahn, C. W. Robust and false positive free watermarking in IWT domain using SVD and ABC. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 49, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2015.12.004 (2016).

Singha, A. & Ullah, M. A. Development of an audio watermarking with decentralization of the watermarks. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(6), 3055–3061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.09.007 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. FRRW: A feature extraction-based robust and reversible watermarking scheme utilizing zernike moments and histogram shifting. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 35(8), 101698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101698 (2023).

Su, Q., Niu, Y., Zou, H. & Liu, X. A blind dual color images watermarking based on singular value decomposition. Appl. Math. Comput. 219(16), 8455–8466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2013.03.013 (2013).

Hu, H. T., Hsu, L. Y. & Chou, H. H. An improved SVD-based blind color image watermarking algorithm with mixed modulation incorporated. Inf. Sci. (NY). 519, 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.01.019 (2020).

Sharma, S., Sharma, H., Sharma, J. B. & Poonia, R. C. A secure and robust color image watermarking using nature-inspired intelligence. Neural Comput. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05634-8 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2024R102) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This project was funded by King Saud University, Riyadh,Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.T. and H.K. conceived and designed the study. M.A.T. developed the theory and performed the experiments. M.S., H.Q., M.A. contributed data or analysis tools. M.H., P.P., and O.A., and A.A.A.E. wrote the manuscript, and conducting the security analysis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tahiri, M.A., Karmouni, H., Sayyouri, M. et al. An improved reversible watermarking scheme using embedding optimization and quaternion moments. Sci Rep 14, 18485 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69511-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69511-3