Abstract

The effective detection of safflower in the field is crucial for implementing automated visual navigation and harvesting systems. Due to the small physical size of safflower clusters, their dense spatial distribution, and the complexity of field scenes, current target detection technologies face several challenges in safflower detection, such as insufficient accuracy and high computational demands. Therefore, this paper introduces an improved safflower target detection model based on YOLOv5, termed Safflower-YOLO (SF-YOLO). This model employs Ghost_conv to replace traditional convolution blocks in the backbone network, significantly enhancing computational efficiency. Furthermore, the CBAM attention mechanism is integrated into the backbone network, and a combined \(L_{CIOU + NWD}\) loss function is introduced to allow for more precise feature extraction, enhanced adaptive fusion capabilities, and accelerated loss convergence. Anchor boxes, updated through K-means clustering, are used to replace the original anchors, enabling the model to better adapt to the multi-scale information of safflowers in the field. Data augmentation techniques such as Gaussian blur, noise addition, sharpening, and channel shuffling are applied to the dataset to maintain robustness against variations in lighting, noise, and visual angles. Experimental results demonstrate that SF-YOLO surpasses the original YOLOv5s model, with reductions in GFlops and Params from 15.8 to 13.2 G and 7.013 to 5.34 M, respectively, representing decreases of 16.6% and 23.9%. Concurrently, SF-YOLO’s mAP0.5 increases by 1.3%, reaching 95.3%. This work enhances the accuracy of safflower detection in complex agricultural environments, providing a reference for subsequent autonomous visual navigation and automated non-destructive harvesting technologies in safflower operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Safflower is a valuable cash crop with medicinal and oilseed properties1. Its market demand is increasing due to the growth of research and development in safflower-related products. Safflower plants produce multiple clusters of flower bulbs, each with varying opening times, making selective harvesting in batches a necessity. Currently, safflower harvesting relies mainly on manual multi-batch picking, which is both labour-intensive and costly. For this reason, the development of robotic technology for safflower harvesting is crucial. Current intelligent automated harvesting equipment relies on GPS/GNSS during autonomous walking in rows. However, it cannot overcome the bending of safflower rows in the field caused by the operation, resulting in injury to the plants. Therefore, deep learning methods were introduced to research the detection of safflower clusters in complex farmland environments and achieve the accurate identification and positioning of safflower clusters within rows. By using safflower clusters as navigation feature points, this establishes a foundation for the visual navigation and positioning required for safflower harvesting robots.

Two primary approaches are used to detect and recognise flower classifications2. One relies on image processing techniques to differentiate flowers from the background based on variations in colour between flowers and their surroundings. The other is a deep learning approach. Jason et al. employed dual cameras, for near and far recognition, to locate and identify flowers. To decrease image processing time, they used a basic Bayesian classifier on reduced colour-segmented regions for distant flower recognition. For near recognition, they utilized RGB-D cameras to reconstruct the three-dimensional plant, identifying recognized flowers with 78.63% accuracy3. Oppenheim et al. (2017) proposed an algorithm for analysing images to detect and count yellow tomato flowers in greenhouses, with 74% accuracy, using adaptive global thresholding, segmentation in the HSV colour space, and morphological cues to identify the flowers4. Image processing-based target detection techniques rely on the analysis and extraction of the colour, texture, and shape features of the safflower target. Despite the low computational costs associated with these methods, their stability and accuracy in detecting safflower targets are limited when faced with sudden changes in lighting, small target sizes, and complex backgrounds.

In comparison to conventional image processing techniques, deep learning-based object detection methods (such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs)) can automatically learn the multi-level features of targets without the need for manually specifying the colour, shape, or other feature parameters. This enables deep learning-based object detection methods to demonstrate enhanced accuracy and resilience, even in challenging environments. The technology used for detecting objects based on their visual characteristics relies on analysing and extracting inherent features such as colour, texture, and shape. Despite the relatively low computational cost, the stability and accuracy of object detection are negatively impacted by sudden changes in illumination and complex backgrounds surrounding the target objects. The field of agriculture has seen a recent uptick in the application of deep learning5,6, whose target detection and recognition techniques include RCNN7, Fast-RCNN8, Mask-RCNN9, SSD10, and You Only Look Once (YOLO)11. Jia et al. (2020) proposed an optimised Mask R-CNN algorithm for the recognition of apples on fruit trees, achieving test accuracy of 97.3%. However, the computational speed was low12. Tian et al. (2019) employed an enhanced SSD algorithm to detect flowers in VOC2007 and VOC2012, with respective accuracies of 83.64% and 87.4%13. Zhang et al. (2022) developed a tomato detection algorithm using an improved RC-YOLOv4, with mean accuracy of 94.44% and a detection speed of 10.71 frames/s14. The YOLO algorithm better balances between detection accuracy and speed, making it more suitable for deployment on mobile devices. However, the problem of reduced detection performance still occurs when coping with the small size and high density of safflower clusters in safflower farmland.

This study aimed to address the aforementioned issues by making several contributions: (1) YOLOv5 was employed as the base model, with the lightweight convolution Ghost_conv enhancing the original backbone network; (2) the CBAM attention mechanism was introduced to suppress unimportant features and enhance the model’s adaptive feature fusion capability; (3) a combined loss function integrating CIOU and NWD was proposed to optimise the convergence speed of the model loss; and (4) the original COCO dataset anchors were updated using the K-means algorithm, focusing on safflower clusters in the field, to enhance the model’s multi-scale safflower detection capability. This study presents an enhanced lightweight safflower detection algorithm based on YOLOv5, SF-YOLO, that addresses the issues of inaccurate detection and poor robustness in complex safflower field environments, both of which impede precise automated harvesting and visual navigation. This offers a viable solution for the enhancement of safflower harvesting machinery.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

The dataset of images employed in this research originated from Hongqi Farm in Jimusar County, Changji Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, situated at 89°12ʹE and 44°24ʹN. The safflower strain used was Jihong 1. The Intel RealSense D455 depth camera and HNONR 20 were utilised for image acquisition, placed directly in front of a homemade safflower picking robot body, as shown in Fig. 1. The viewing angle ranged from 20 to 45° to capture images with resolutions of 1080 × 720 and 1920 × 1080. To enhance the robustness and generalisation of the model, we took into account factors such as time and weather conditions during data collection. The dataset was augmented through image enhancements, including rotation, noise perturbation, blurring, and colour transformation. Periods of sunny weather included early morning, noon, and afternoon, as depicted in Fig. 2a–c; overcast conditions are shown in Fig. 2d; Fig. 2e shows images captured at dusk; and Fig. 2f shows LED fill-in lighting at night.

Dataset production

Complex datasets were created by combining images captured from various angles, lighting, and weather conditions, enabling automated harvesting equipment to adapt to a variety of working conditions for both identification and harvesting purposes. We aimed to produce versatile datasets that can be used in different settings. Safflower threads typically display shades of reddish-orange and yellowish-orange (in their immature state) in the field, owing to differing degrees of maturity. Given the current market demand for safflower filaments, the two colours are not differentiated, and are graded similarly. Given the inconsistent growth of safflower plants in the field, and the impact of weather leading to fallen plants, as well as instances of plants shading each other and causing significant leaf damage, data marking requires us to exclude safflower plants with shading exceeding 75%. In the process of marking, it is important to avoid flower buds, stalks, and leaves. Figure 3 depicts the Ji Hong 1 safflower variety. The data were annotated using the open-source application LabelImg, and the data were in PASCAL VOC dataset format. The label name for safflower was “safflower.” An example of the annotation is shown in Fig. 4.

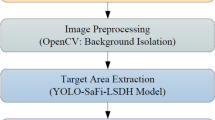

Safflower cluster detection

YOLOv5 network architecture

The YOLOv5 network comprises an input layer, backbone network, neck network, and prediction output layer. The image input to the backbone network undergoes convolution to obtain the feature map, which is forwarded to the neck network for multi-scale feature fusion, incorporating upsampling and downsampling. The combined features output from layers 17, 20, and 23 are forwarded to the output layer. The confidence score, prediction category, and target frame coordinates can then be obtained after non-maximum suppression and other processing15. The framework diagram for the YOLOv5 network is presented in Fig. 5.

YOLOv5 model version determination

YOLOv5 has five versions, with different network depths and numbers of residuals. We evaluated the performance of YOLOv5n, YOLOv5s, YOLOv5m, YOLOv5l, and YOLOv5x at detecting safflower. We trained each model on a self-constructed safflower dataset, with the aim of identifying the most appropriate version of YOLOv5. Our findings are displayed in Table 1. A model’s efficacy was assessed by its precision (accuracy), F1-score, mean average precision (mAP), GFlops (model calculations), and number of model parameters (Params), where

True positives (TPs) refer to cases where the model correctly identifies an object, while false positives (FPs) refer to cases where the model predicts an object where there is none. The average precision (AP) is the area under the precision-recall curve. Other factors that can affect model performance include the kernel size (K), number of channels (C), size of input image (M), and number of iterations (i).

YOLOv5x, YOLOv5l, and YOLOv5m have greater detection accuracy than YOLOv5n, but their more intensive computation makes them unsuitable for mobile use. YOLOv5n is more lightweight, but has poor accuracy. Balancing computation and accuracy, we selected YOLOv5s, and enhanced it to reduce computation (params, GFlops) while maintaining detection accuracy.

Improvement strategies

We present a safflower detection model for SF-YOLO. We seek a reduced computational burden, given the complex background and environmental variables that characterize safflower farmland. To this end, we replace the standard convolutional block in the backbone network with the lighter Ghost_conv block. We embed the attention module after the SPPF module in the backbone network, which enables the model to focus on relevant information and enhances its self-adaptive fusion ability, ultimately improving the recognition rate. The initial model’s LGIOU loss function is replaced by the fusion L(CIOU+NWD) loss function. We refine the YOLOv5 model’s initial anchor frame using K-means clustering to better suit small- and medium-sized safflower target detection. Figure 6 depicts the structure of the improved SF-YOLO network model.

Model lightweighting

Due to computational limitations, the prediction model is too large for mobile deployment. The numbers of parameters and computations are reduced by replacing the CBS module in the backbone network with the Ghost_conv module from the Ghostnet network16, whose initial phase involves the application of conventional convolution to produce feature maps with fewer channels, thus lowering computational demands. Subsequently, inexpensive operations are performed on the feature maps to obtain new ones and further reduce computation. The two groups of feature maps are combined to generate the output feature maps, as shown in Fig. 7.

CBAM attention mechanism

Woo et al. (2018) proposed CBAM, a mechanism that focuses on important features in both channel and spatial dimensions and suppresses unimportant features to improve the accuracy of safflower detection17. The process is as follows. The channel dimension attention mechanism is processed, the input feature map F (H × W × C) is subjected to global max pooling and global average pooling, the two obtained feature maps are fed into a multilayer perceptron (MLP), the two features of the output are summed, and the channel feature map (channel attention feature), i.e., M_c, is generated by sigmoid activation, as shown in Eq. (6). In the second step, M_c is used as the input feature, which undergoes global max pooling and global average pooling. The resulting feature maps are then concatenated along the channel dimension and then passed through a 7 × 7 convolution followed by Sigmoid activation to generate the spatial attention feature map, M_s, as shown in Eq. (8). The channel dimension attention mechanism and the spatial dimension attention mechanism are illustrated in Fig. 8.

where F is the input feature; F1 is the channel attention mechanism feature layer; and F2 is the CBAM module output feature.

Improvement of K-means-based anchor frame mechanism

The YOLOv5 initial anchor frame is obtained by using K-means clustering for the COCO dataset, and a genetic algorithm to adjust the anchor frame during dataset training. The size of the anchor frame influences the convergence speed and accuracy of the model. The safflower dataset produced in this study was labelled with small- and medium-sized targets, the 80 category targets in the COCO dataset were of different sizes and categories, and the initial anchor frame of YOLOv5 was not suitable for the constructed dataset. Therefore, we used K-means clustering to obtain new safflower anchor frames in the dataset. The clustering results are shown in Table 2.

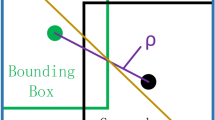

Loss function improvement

The loss function is used to assess the difference between the predicted and true values of a model. We used LGIOU, LDIOU, and LCIOU to calculate the loss function in YOLOv5, where

where IOU is the intersection and merger ratio; \(D_{2}\) is the Euclidean distance between the centroids of the predictive and real frames; \(D_{c}\) is the diagonal distance, i.e., the smallest closure region that can contain both the predictive and real frames; v measures the consistency of the aspect ratio; and wgt and hgt are the respective widths and heights of the real frames.

The safflower field growing environment is complex, and safflower targets are not only small- and medium-sized, but there are a large number of them. LCIOU provides more comprehensive loss information than LGIOU and LDIOU by considering the shape, size, centre position, and aspect ratio error of the bounding box. LCIOU takes into account the distance between the centres of bounding boxes, which are more accurately positioned. On the basis of LCIOU, the normalised Wasserstein distance (NWD) algorithm is integrated, and the balancing coefficient β is set to accelerate the convergence of the model loss. We set β to 0.8, and the NWD algorithm is calculated as

where \(W_{2}^{2} \left( {N_{a} ,N_{b} } \right)\) is the Gaussian distribution between bounding boxes A and B; \(x_{A}\), \(y_{A}\), \(x_{B}\), \(y_{B}\) are the respective centre coordinates x, y of bounding boxes A and B; \(w_{A}\), \(h_{A}\), \(w_{B}\), \(h_{B}\) are the respective lengths and widths of bounding boxes A and B; and \(NWD\left( {N_{a} ,N_{b} } \right)\) is a similarity measure of bounding boxes A and B.

In this study, the original LGIOU is replaced by the improved LCIOU as the loss function of SF-YOLO. LCIOU is based on LDIOU, introducing a term αv, where α is a balancing parameter not involved in the gradient calculation18,19. The total loss LCIOU+NWD after using the improved CIOU is

Figure 9 shows the loss decline curves before and after improvement. The improvement converges quickly in the first 100 rounds of training.

Results and discussion

Table 3 shows the configuration environment for this experiment. The dataset consisted of 6554 safflower images, which were divided into training, test, and validation sets in a 7:2:1 ratio, resulting in 4970 images for training, 1420 images for validation, and 710 images for testing. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01, and the learning rate was adjusted to accelerate convergence. Considering the memory limitations of the CPU, the batch size was set to 18, the number of training rounds was set to 300, and 640 × 640 resolution was selected.

Ablation experiments

Ablation experiments were conducted utilising a test set comprising 710 images captured at various times throughout the day. This study focused on the introduction of the Ghostmodel, updating anchor boxes via K-means clustering, and incorporating attention mechanisms, with the aim of assessing the performance of SF-YOLO in detecting safflower clusters in agricultural fields. The results of the experiment are presented in Table 4. The improvement of the model backbone network structure reduced the complexity of the model and the number of parameters, and it also enhanced the comprehensive performance and accuracy of the model. Compared with the initial YOLOv5s model structure, the introduction of Ghostmodel resulted in decreases in GFlops and Params by 15.2% and 24.4%, respectively, and 0.8% in mAP. The introduction of CBAM after the SPPF layer of the backbone network, replacement of the fusion loss function with LCIOU+NWD and updating of anchor frames resulted in a small change in GFlops and Params, but mAP increased by 2.1%. Following the implementation of improvements to the model, the Precision value exhibited an upward trajectory, increasing from 91.9% in the original model to 94.1%. The Recall value had a slight decline, decreasing from 92.6 to 92.3%. However, both the mAP0.5 and Precision values exhibited an upward trend, indicating that the model became more reliable in detecting actual positive samples while reducing false identifications. This renders it suitable for practical detection and automated harvesting tasks in safflower fields.

Experiments comparing performance of different models

To verify the comprehensive performance of the proposed SF-YOLO model for inter-row safflower detection, it was compared with the Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv4, YOLOv8, YOLOv5, and YOLOv9-c models. The results are shown in Table 5, which indicates that the SF-YOLO model had 31.4%, 17.9%, 7.1%, 10.65%, 1.5%, and 0.2% higher mAP values than Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, and YOLOv9-c, respectively. After replacing the original convolutional blocks of the backbone network, the GFlops of SF-YOLO were reduced by 927.17 G, 259.17 G, − 1.1 G, 127.9 G, 14.4 G, 1.8 G, and 222.6, respectively, while Params were reduced by 22.49 M, 17.62 M, 2.68 M, 57.95 M, 105.27 M, 1.02 M, and − 8.9 M, respectively. YOLOv8s has the same mAP as SF-YOLO, but with higher GFlops and Params by 14.4 G and 105.27 M, respectively. Furthermore, although YOLOv9 has demonstrated considerable promise on a number of publicly available datasets, it has not yet fully adapted to specific conditions such as small safflower sizes, dense distributions, and other particular challenges. Its mAP0.5 and F1 scores were both slightly inferior to those of SF-YOLO. The F1 score of SF-YOLO is markedly superior to those of other models, suggesting that the model exhibits enhanced precision in recognising small safflower targets and maintains robust performance. Considering the accuracy and complexity of the model, SF-YOLO is more suitable for deploying and completing the safflower detection task on mobile devices.

SF-YOLO model detection effect

Using the improved SF-YOLO, the safflower detection results under different light and weather conditions are shown in Fig. 10. To ensure comprehensive and objective results, six scenarios were selected for testing: sunny day-early morning, sunny day-noon, sunny day-afternoon, evening, fill-in light, and cloudy day. Figure 11 shows the detection results of the original YOLOv5 model, where red boxes mark successfully detected safflowers, and blue boxes mark the target safflowers. It is seen that SF-YOLO maintains stable and accurate detection under different light and weather conditions, while during periods of strong lighting changes, the initial YOLOv5s model may fail to detect some safflower targets during the inference process, as shown in Fig. 11a–f. The experimental results verify the superiority of SF-YOLO in detecting safflower in different farmland scenarios.

Model visualisation and analysis

We used heat maps to visualise, compare, and analyse detection performance of the YOLOv5 and SF-YOLO models by indicating the model’s attentional weights for different regions and features through the colour depth of the target centre. To further understand the model’s internal attention to regional features, the features output from the penultimate layer of the model were subjected to gradient-weighted activation mapping using Grad-CAM. Figure 12 shows the detection effect of SF-YOLO under different light and weather conditions, and Fig. 13 shows the detection effect of the original model. It can be seen that SF-YOLO has better robustness and adaptability in a complex farmland environment.

Conclusion

To achieve accurate and fast detection of safflower with limited computational capacity in a complex environment, we proposed an improved target detection model, SF-YOLO, which adopts Ghost_conv to replace the original convolutional block in the backbone network to improve computational efficiency. The CBAM attention mechanism was embedded in the backbone network, and the fusion LCIOU, LNWD loss function LCIOU+NWD was introduced to extract features more accurately, enhance the adaptive fusion ability of the model, and accelerate loss convergence. An anchor frame obtained by K-means clustering was used to update and replace the original anchor frame, for better adaption to multiscale reddish colours in farmland. Data enhancement techniques including Gaussian blurring, Gaussian noise, sharpening, and channel disruption were employed to further improve the generalisation ability of the model, making it robust to lighting, noise, and angle changes. SF-YOLO outperformed the original YOLOv5s model in experiments, where GFlops and Params decreased from 15.8 to 13.2 G and from 7.013 to 5.34 M, respectively, which are decreases of 16.6% and 23.9%, and the mAP0.5 of SF-YOLO improved by 1.3–95.3%. This indicates that SF-YOLO can effectively and accurately detect safflower in complex environments, using computationally underpowered devices.

In summary, SF-YOLO achieved the efficient and accurate detection of safflower in a complex environment with limited computational capacity, which is of great significance for the practical application and development of agricultural automation technology.

Although SF-YOLO can achieve the accurate detection of safflower among multi-agricultural fields, there are still shortcomings: (1) Safflower varieties are diverse; however, the dataset did not account for different safflower variety types, and this experiment solely focused on the ‘Jihong 1’ variety. (2) We did not consider the possibility of multiple safflowers overlapping, which the model will treat as only one safflower. In the future, features such as instance segmentation will be used to better overcome the problem of the overlapping of flowers leading to misrecognition.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Wang, X. R., Xu, Y., Zhou, J. P. & Chen, J. R. Safflower picking recognition in complex environments based on an improved YOLOv7. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 39(6), 169–176 (2023).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521(7553), 436–444 (2015).

Ohi, N., et al. Design of an autonomous precision pollination robot. in 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, (2018).

Oppenheim, D., Edan, Y. & Shani, G. Detecting tomato flowers in greenhouses using computer vision. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Eng. 11(1), 104–109 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Lightweight detection networks for tea bud on complex agricultural environment via improved YOLO v4. Comput. Electron. Agric. 211, 107955 (2023).

Gui, Z. et al. A lightweight tea bud detection model based on Yolov5. Comput. Electron. Agric. 205, 107636 (2023).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, (2014).

Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, (2015).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, (2017).

Liu, W., et al. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. in Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer International Publishing, (2016).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, (2016).

Jia, W. et al. Detection and segmentation of overlapped fruits based on optimized mask R-CNN application in apple harvesting robot. Comput. Electron. Agric. 172, 105380 (2020).

Tian, M., Hong C. & Qing, W. Detection and recognition of flower image based on SSD network in video stream. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. vol. 1237. No. 3. IOP Publishing, (2019).

Zheng, T., Jiang, M., Li, Y. & Feng, M. Research on tomato detection in natural environment based on RC-YOLOv4. Comput. Electron. Agric. 198, 107029 (2022).

Yu, X., Kong, D., Xie, X., Wang, Q. & Bai, X. Deep learning-based target recognition and detection for tomato pollination robots. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 38(24), 380 (2022).

Han, K., et al. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, (2020).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J. Y. & Kweon, I. S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. in Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), (2018).

Wang, Q., Ma, Y., Zhao, K. & Tian, Y. A comprehensive survey of loss functions in machine learning. Ann. Data Sci. 1–26 (2020).

Zhang, Y.-F. et al. Focal and efficient IOU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing 506, 146–157 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (No. 2022D01A177). Funding was provided by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G. and T.W.; methodology, H.G. and T.W.; software, H.G. and T.W.; valida-tion, T.W.,H.G. and G.G.; formal analysis, T.W.; investigation, T.W.; resources, H.G.; data curation, Z.Q. and H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G. and T.W.; writing—review and editing, H.G.; visu-alization, T.W.; supervision, H.G.; project administration, H.G.; funding acquisition, H.G. All au-thors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, H., Wu, T., Gao, G. et al. Lightweight safflower cluster detection based on YOLOv5. Sci Rep 14, 18579 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69584-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69584-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Lightweight and efficient deep learning models for fruit detection in orchards

Scientific Reports (2024)