Abstract

Mosquito-borne diseases kill millions of people each year. Therefore, many innovative research and population control strategies are being implemented but, most of them require large-scale production of mosquitoes. Mosquito rearing depends on fresh blood from human donors, experimentation animals or slaughterhouses, which constitutes a strong drawback since high blood quantities are needed, raising ethical and financial constraints. To eliminate blood dependency and the use of experimentation animals, we previously developed BLOODless, a patented diet that represents an important advance towards sustainable mosquito breeding in captivity. BLOODless diet was used to maintain a colony of Anopheles stephensi for 40 generations. Bloodmeal appetite, fitness, Plasmodium berghei infectivity, whole genome sequencing and microbiota were evaluated over time. Here we show that BLOODless can be implemented in Anopheles insectaries since it allows long-term rearing of mosquitoes in captivity, without a detectable effect on their fitness, infectivity, nor on their midgut and salivary microbiota composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

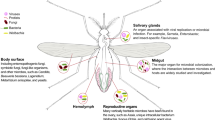

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. In the recent past, new approaches to control and reduce insect mosquito populations have been implemented based on population replacement and suppression strategies by releasing genetically modified1,2 or Wolbachia-infected3 mosquitoes to halt disease transmission. A critical step for these innovative control measures is that the rearing program must be able to raise large numbers of healthy insects that exhibit normal behaviour and fitness4. Maintenance of insect colonies for research has always been challenging since, until now, solutions have largely relied on blood from human donors, slaughterhouse blood from various animal types, and sedated or restrained live animals. All these solutions encounter safety issues, high variability among different batches, rigorous bureaucracy, and controlled temperature chain for shipping and storage of blood. Hence, these facts increase research costs, and, in most countries, the use and handling of live animals requires special licences and specific facilities5. The use of donated human blood also detains a central limitation since it carries the risk of blood-borne pathogens. In addition, blood has a shelf life of 2–4 weeks having to be acquired frequently which boosts the overall cost. Further, the animal source of blood or anticoagulant used, might have an impact on mosquito fecundity and viability6, which constitutes a major bottleneck when rearing mosquitoes and the large-scale implementation of control strategies into the wild. Therefore, the implementation of artificial diets that efficiently simulate a bloodmeal is crucial for replacing vertebrate blood in drug and vaccine clinical trials and for mosquito release into the wild. For that reason, we have recently formulated BLOODless, a blood-free artificial diet for rearing Anopheles mosquitoes in captivity7. BLOODless is an innovative patented diet (PCT/IB2019/052,967, WO/2019/198,013, US2021030025A1) representing a considerable advance over the current state-of-art on the development of artificial diets. In addition, it is a breakthrough on Anopheles rearing under laboratory conditions as it eliminates ethical constraints and security issues associated with the use of live animals for research. Over the past years we have maintained an A. stephensi insectary exclusively fed on BLOODless diet. However, to enable the implementation of BLOODless on a worldwide scale, the present work intended to deepen our knowledge on the potential long-term effects of BLOODless on (i) bloodmeal appetite; (ii) behavioural food preferences; (iii) fitness, assessed through longevity and wing size; (iv) Plasmodium infection rates; (v) progeny midgut and salivary microbiota composition, and (vi) allele frequencies, as assessed through whole-genome sequencing.

Results

Establishment of the BLOODless colony

The blood-free colony started on September 2020, from the founder population of A. stephensi mosquitoes reared with CD1 mice blood for more than 10 years. Both colonies were maintained at similar conditions and methodology. The 40th generation of mosquitoes exclusively bred without blood has been reached, and pupae production is increasingly close to the standard blood insectary (Figure S1).

Bloodmeal appetite

To test if the exclusive feeding of mosquitoes with BLOODless diet affected the females’ appetite and attraction for mouse blood over time, a bloodmeal consisting of a healthy anesthetized CD1 mouse was offered to females from both insectaries (Blood and BLOODless diet) on different mosquitoes’ generations (F3, F7, F9 and F38). The proportion of females that fed was evaluated by counting the number of females that were fully engorged and females that did not feed, by the end of the membrane feeding. The feeding proportion is significantly different between Blood and BLOODless diet (controlling for generation, ANCOVA F1,21 = 12.099, P = 0.002; Supplementary Table S1), with higher proportions of feeding females originating from the blood-free colony (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that bloodmeal appetite and mouse attraction are not adversely impacted by the exclusive BLOODless diet feeding.

Feeding behaviour of female mosquitoes raised on blood versus mosquitoes raised on BLOODless diet. (A) Appetite and attraction to a standard vertebrate bloodmeal of female mosquitoes raised on blood versus mosquitoes raised on BLOODless diet. Three independent experiments were performed for each generation and colony. The feeding proportion values are represented as the mean + SD of three feeding experiments. Significantly different proportion of feeding was detected between Blood and BLOODless diet, controlling for generation (ANCOVA F1,21 = 12.099, P = 0.002); (B) Dietary choice between a standard vertebrate bloodmeal or a blood-free diet. Three independent experiments were performed on the 38th generation of female mosquitoes originating from both insectaries (Blood or BLOODless). Results are expressed as a percentage of the feeding rate for each type of meal. In grey are represented the female mosquitoes that did not feed. On the left side of the plot are the results for females originating from the BLOODless diet whereas on the right side of the plot are represented the results for female mosquitoes from the Blood colony. No significant differences were found between insectaries regarding the proportions of females preferring Blood (Mann–Whitney, p = 0.7).

Dietary choice

To test female mosquitoes’ meal preference, two different Hemotek® reservatoirs, one containing mouse blood and the other containing BLOODless diet, were offered simultaneously to the same cage. Three independent experiments were performed on generation 38, for both females originating from the Blood colony and females from the BLOODless insectary.

On average, 51.5% females from the BLOODless insectary preferred the artificial diet, 34.9% chose Blood and 13.5% did not feed. Concerning the females originating from the Blood insectary, 38.4% engorged the BLOODless diet, 41.6% preferred the Blood and 20% did not feed (Fig. 1B).

Fitness

Mosquito fitness is crucial for the success of a mosquito colony and their survival when released into the wild. As fitness of mosquitoes may be affected by the long-term rearing on blood-free diets, we evaluated fitness in insectary rearing conditions across different generations. Mosquitoes’ longevity and wing length was assessed and compared to the former colonies bred on blood.

Mosquitoes from the BLOODless diet insectary presented a longer life span when compared to mosquitoes bred on the standard vertebrate Blood (controlling for sex and generation, ANCOVA F1,8 = 55.5, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Table S1).

Fitness experiments on A. stephensi mosquitoes from both colonies. (A) Life expectancy of A. stephensi mosquitoes from both colonies. Longevity of mosquitoes both from the standard Blood colony and the BLOODless diet colony was assessed on F6, F9 and F38 generations. Life span was calculated using the dates of adult emergence and death of 15 males and 15 females from each insectary. Results are expressed as the mean + SD mosquito life span per diet group and generation. (B) Wing length of mosquitoes raised on Blood versus mosquitoes raised on BLOODless diet. The distance from the axial incision to the R4 + 5 vein excluding the fridge seta was used to measure mosquitoes wing length as a fitness indicator. Size was evaluated for females and male mosquitoes from each dietary group on generations F2, F4, F6, F8 and F38. Values are represented as the mean + SD. Red: Blood insectary; Yellow: BLOODless diet insectary.

The wing size was significantly different between sexes and across generations but not between meal types (ANCOVA F1,16 = 0.95, P = 0.343 for the meal term; F1,16 = 5.35, P = 0.034 for generation; F1,16 = 19.14, P = 0.0005 for sex) (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Table S1). As expected, the wing size of males was smaller than that of females. The observed difference in wing length, with smaller wing length in males in generation F38 was unexpected (Fig. 2B).

Plasmodium berghei infections

Nutritional resources taken prior to an infectious bloodmeal play a decisive role in mosquito-parasite interaction. The mosquito, the parasite, and the microbiota in the mosquito gut, all play a critical role in the infection outcome. Therefore, we investigated if the BLOODless diet impacts the outcome of Plasmodium berghei infections. Mosquitoes reared on BLOODless diet were experimentally infected with P. berghei (rodent malaria) and the outcome of infection was compared with mosquitoes reared on Blood. Infection rate and intensity was assessed by evaluating the presence of well-developed oocysts in the midguts between days 7 and 10 post-infection. Infections were performed on generations 23, 27 and 38.

No significant differences were observed on the infection rate (Fig. 3A) when comparing females coming from both insectaries (Blood and BLOODless), controlling for generation (ANCOVA F1,3 = 0.003, P = 0.957; Supplementary Table S1). Regarding the infection intensity, it was significantly higher on females originating from the BLOODless insectary (Fig. 3B), controlling for generation (ANCOVA F1,3 = 29.473, P = 0.012; Supplementary Table S1).

Plasmodium berghei infections. Females from both insectaries (BLOODless diet and Blood) fed on a P. berghei-infected CD1 mouse along different generations. (A) The rate of the infection is represented by the percentage of infected females. This value was calculated by investigating the presence or absence of parasite oocysts on females’ midguts. (B) The average number of oocysts present on the midguts of infected females was counted, revealing the infection intensity.

Effects of BLOODless diet on mosquito microbiota

Mosquito microbiota can vary with environmental conditions8,9 and the blood source10, indicating that the diet might influence mosquito midgut microbiota, and consequently, impact several physiological processes, such as development, digestion and reproduction11. Therefore, we tested if the long-term use of the BLOODless diet for A. stephensi rearing would have an impact on mosquito microbiota. Midguts of male and female mosquitoes, and salivary glands of females were compared before and after the use of BLOODless diet for 10 generations.

The total number of sequence reads obtained from the 16S rRNA Illumina sequencing on the 20 samples analysed (18 experimental + 2 controls) was 43.9 M reads, with a mean of 2.3 M reads per experimental sample (minimum of 1.5 and maximum of 3.0 M reads) (Supplementary Table S2). After quality control (reads > = Q30), there was a mean of 2.1 M reads per sample. Paired-end reads were merged to reconstruct the original full-length 16S amplicons producing a mean of 612.6 thousand amplicons per sample. A total of 1,932 features were found after dereplication, clustering and removal of chimera. The total number of OTUs found by taxonomic assignment and after removal of mitochondrial sequences, was 1,529.

The relative frequencies of bacteria at the order level were dominated by Enterobacterales in female midguts regardless of how the insectary was kept (BLOODless diet or Blood), while female salivary glands, coming both from BLOODless or Blood insectaries, were richer on Acetobacterales (Fig. 4). Midguts from males reared on blood were also dominated by Enterobacterales, like female’ midguts, but midguts from males reared on BLOODless diet were instead dominated by Flavobacteriales (Fig. 4). Order Enterobacterales was mainly composed of families Enterobacteriaceae (mainly genus Cedecea), Morganellaceae (single species present was Wigglesworthia_glossinidia), Yersiniaceae (mainly Yersinia, Serratia and an unidentified genus). Order Acetobacterales had only one family present, Acetobacteraceae, mainly composed by genus Asaia. Order Burkholderiales was dominated by family Burkholderiaceae (genus Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia and genus Ralstonia) (Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S3).

Alpha and beta diversity analyses. (A) Observed features—number of OTUs per sample; (B) Shannon’s diversity index; (C) Simpson's Index by type of meal (BLOODless: yellow or Blood: red), by sex (Females or Males) and by type of tissue (Midguts or Salivary Glands); (D) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances.

The positive control (mock sample) used was mainly composed of Pseudomonas (order Pseudomonadales, family Pseudomonadaceae), Escherichia-Shigella and an unidentified genus (order Enterobacterales; family Enterobacteriaceae), Listeria (order Lactobacillales, family Listeriaceae) and Bacillus (order Bacillales, family Bacillaceae) (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure S3).

The negative control (no DNA) produced, as expected, a much lower number of sequenced reads (51,310 reads after quality control) and it was composed mainly unidentified families of Oscillospirales and of Lachnospiraceae, genus Methylobacterium-Methylorubrum (order Rhizobiales), genus Massilia (order Burkholderiales, family Oxalobacteraceae) and genus Acinetobacter (order Pseudomonadales, family Moraxellaceae) (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure S3).

The bacterial taxonomic variability within samples (alpha diversity) based on number of OTUs per sample, and Shannon and Simpson indexes for the different groups are depicted in Fig. 5. No significant effect of type of meal or type of tissue was found on any of the measures, but Sex showed a significant effect on Shannon and Simpson indices (Factorial ANOVA, F = 5.875, p = 0.0295 and F = 6.462, p = 0.0235, respectively; Supplementary Table S5).

The visualization of differences in microbiome composition between samples, based on Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA), showed a distinction of the midgut of males fed with BLOODless diet from the remaining samples on axis 2 (23.9% explained variation) (Fig. 5). As seen previously (Fig. 5D) this group showed reduced Acetobacterales and increased Flavobacterales. Axis 1 (40.8% explained variation) distinguished salivary glands’ microbiomes from the remaining samples (Fig. 5D). The salivary glands were characterized by increased Acetobacterales and decreased Enterobacterales (Fig. 4).

The permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), based on Bray–Curtis distances, revealed significant differences between tissue types (p = 0.001) and sex (p = 0.005) but not between type of meal (p = 0.08) (Supplementary Table S5).

Genetic changes between the control and BLOODless diet colony

In the whole genome sequencing, the number of properly paired mapped reads in each sample, after quality control, trimming and mapping, ranged from 73 to 92 million reads (Supplementary Table S6). Considering each sample separately, the median number of reads covering each site in the alignment (coverage) ranged from 54 × to 65x (Supplementary Table S6). The number of polymorphic sites was around 3 million in each sample (Supplementary Table S6). The overall number of nucleotide sites in the multiple-sample alignment was 162,979,953 and the total number of polymorphic sites considered were 2,633,683. The mean nucleotide diversity within each sample ranged from 0.0052 to 0.0064 (Table 1). The median of the mean nucleotide diversity for the control samples was 0.0060 and for the BLOODless diet samples was 0.0056, with no statistical difference detected (Mann–Whitney U test = 1.5, P = 0.184). The mean FST values between pairs of samples ranged from 0.027 to 0.038 (Table 1). Between Blood samples (control), the median of the mean FST was 0.030 and between BLOODless diet samples it was also 0.030, with no statistical difference between them (Mann–Whitney U test = 2.0, P = 0.275). Between BLOODless and Blood samples the median mean FST was 0.032.

The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test resulted in 3785 sites with p values lower than 1E−10, which means that these sites have significant differences in allele frequencies between the control and the artificial diet and that these differences are consistent between replicates. From these, 1374 showed allele frequency increase from an initial minor allele in all three replicates. The SNP regions (200 upstream and 200 downstream of the SNP) were blasted against the NCBI protein database and 164 SNP regions had blast hits, mainly with A. stephensi and a few with A. funestus and A. maculipalpis (Supplementary Table S7). Of these, gene ontology annotation was possible for 65 sequences and indicated the following higher level GO categories for biological processes: localization, response to stimulus, cellular processes, metabolic processes, and biological regulation (Supplementary Table S7). When a finer analysis of the identified genes was performed a high proportion of genes (17/88, 19.32%) could be associated with transcription regulation and mRNA processing/regulation were observed.

Discussion

Mosquito production in captivity is crucial for carrying out innovative control measures that envisage infectious diseases elimination in endemic countries. Therefore, replacing vertebrate blood for mosquito rearing and control with artificial diets that simulate a bloodmeal is imperative. The capacity of seeking a meal (blood or diet) is the first step towards egg production, which was not abrogated by using BLOODless diet (Supplementary Figure S4). Membrane feeding assays can have lower feeding rates than direct feeding12 and feeding habits can evolve in a mosquito population13. Even so, BLOODless raised mosquitoes showed higher feeding rates towards animals, when compared to females from the Blood colony, from the 3rd generation until the 38th. Demonstrating that even though females were fed BLOODless diet exclusively on an artificial apparatus for more than 3 years, their voracity and desire towards a living being (in this case, an anesthetized mouse) was not diminished. Moreover, when meal preference was tested by offering simultaneously mouse blood and BLOODless diet, both by Hemotek® membrane feeding system, female mosquitoes showed no preference.

Lifespan, an important life history trait, in accordance with our previous work7, and literature on differences on sex life span, females from both colonies exhibited longer lifespans than their male counterparts. Furthermore, both male and female mosquitoes raised on the BLOODless diet showed extended longevity compared to those bred on the conventional vertebrate Blood. Considering laboratory-oriented research strategies, it may be an advantage to raise the lifespan of mosquitoes because this allows increasing egg production by increasing the number of feedings per generation.

The wing size of mosquitoes is important for various aspects of their biology and behaviour, namely their flight ability, survival and reproduction14, host-seeking behaviour, evolutionary adaptations, Plasmodium spp. infectivity15, among others. Wing size has been used as a proxy of fitness19, which was not affected by BLOODless. As environmental and larvae rearing conditions are known to affect this parameter20, both colonies were reared in similar conditions.

The prevalence and intensity of P. berghei infection are influenced by the larval diet, probably through a mechanism dependent on the microbiota21, but little is known in relation to adult’s diet22.

Our results showed no significant differences on infection rates when comparing females from both colonies, indicating that the long-term use of BLOODless does not affect mosquitoes’ permissiveness to Plasmodium. However, females originating from the BLOODless insectary showed more oocysts on the midguts of infected mosquitoes23. The connection between oocysts density and sporozoites load in salivary glands is not fully comprehended 24. The number of Plasmodium falciparum ruptured oocysts have a strong positive corelation with sporozoites numbers in the salivary gland and saliva inoculate25. Estimates based on P. berghei are not the most accurate model to predict the success rate of oocysts to sporozoites of human parasites, as this laboratory model generates numerous oocysts, of which a significant portion probably never undergoes complete development26. Further, due to intrinsic or extrinsic variations on sporozoite production by oocysts, intensity of infection might not be a proxy of transmission27,28. Even though our data shows a significantly higher oocyst load (total ruptured + un-ruptured) on BLOODless-fed females, further investigation is required to conclude how this might affect transmission.

No significant differences were observed on the microbiota of females from both insectaries (BLOODless or Blood). Several prevalent genera/species dominate most of the gut microflora, encompassing the previously described Enterobacter, Rhanella, Klebsiella, Serratia, Pseudomonas, Elizabethkingia, Asaia, and Raoultella29.

Surprisingly, the relative frequencies of bacteria at the order level present on the midguts from males originating from the BLOODless colony were Flavobacteriales, while males from the Blood insectary presented mainly the order Enterobacterales. The composition of the gut microbiota is influenced by various factors, such as the quality of rearing water, the larval food and the adult’s diet9. Since all these components were similar in both insectaries, to rule out that male mosquitoes have not changed their feeding habits, BLOODless diet was offered to males from both insectaries using an artificial membrane feeding system and, confirmed that males do not feed on the diet (data not shown). Further studies are needed to explain this observed difference.

The whole genome pooled sequencing analyses are constrained by the small number of individuals per pool (n = 10), which limits the allele frequency estimation. The results presented here are indicative and can be the basis for additional sequencing on a larger number of samples. The low mean nucleotide diversity (around 0.006) found in all samples is expected in populations likely subjected to strong bottleneck effects as these mosquito colonies. The differences between control and artificial samples in nucleotide diversity and pairwise differentiation was very small and not statistically significant. The identified SNPs showing consistent allele frequency changes between Blood and BLOODless populations can be candidates for further investigation to understand if they are involved in adaptation to the new dietary regime or if these changes are due to genetic drift. An experimental evolution approach would be needed to understand the effects of selection, historical contingencies and chance30.

In summary, the data presented in this article allow us to conclude that the previously developed artificial diet, now tested in the long-term, can be implemented in all Anopheles spp. production insectaries without affecting the fitness, genome, microbiota, and vector competence of the bred mosquitoes. The BLOODless diet, in addition to being an innovative and unique product, represents a more sustainable and ethical solution than the blood sources currently used in captive mosquito vectors production.

Methods

Ethical considerations

CD1 mice (Mus musculus) were used to maintain the standard A. stephensi mosquito colony. All animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the Portuguese law and ARRIVE guidelines for the use of laboratory animals. The protocols used were approved by Direção-Geral de Veterinária, Ministério da Agricultura do Desenvolvimento Rural e das Pescas, Portugal (id approvals: 023,351 and 023,355). Experiments were performed by fully licensed researchers by DGAV and legally accredited for animal manipulation in compliance with the Portuguese law, DL 113/2013 de 7 de Agosto, which transposes the Directive 2010/63/UE of the European Union.

BLOODless A. stephensi colony implementation

To investigate the effect of the long-term use of BLOODless on Anopheles spp. mosquitoes, a colony of A. stephensi mosquitoes fed exclusively on the artificial diet was implemented (we have now reached the 40th generation). The BLOODless colony was kept inside 20*20*20 cm net cages and fed with 10% glucose solution ad libitum, under optimal insectary conditions (26 ± 1 °C, 75% humidity and a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle). For all the experiments, an A. stephensi control group fed exclusively on blood from healthy CD1 mice was kept on another insectary within the same building and sharing the same water source, food, maintenance methods and reared under the same standard insectary conditions. Pupae were collected daily into a small water container which was placed inside a mosquito cage with a 10% glucose solution to let adult mosquitoes emerge and mate. Larvae were fed daily with a mixture of Tetra Goldfish flakes and Astra Pond sticks fish food (proportion of 1:2), and their water containers were cleaned and changed once a week. The adult female mosquitoes from each insectary were fed with BLOODless or mice blood once a week. Forty-eight hours after the feeding, an egg plate consisting of a small water container with a filter paper was placed inside the cage and female mosquitoes were allowed to lay their eggs for 48 h. To assess fecundity, females were individualized, and each was allowed to lay eggs separately, which were then counted using a stereoscope (Supplementary Figure 4). The eggs were then collected and incubated in water so they could develop into the larval stages.

Along 38 generations, several parameters related to mosquito fitness (life expectancy on F6, F9 and F38; wing length on F2, F4, F6, F8 and F38), genetic selection and microbiota (F10) were evaluated.

BLOODless diet membrane feedings

BLOODless diet was prepared as described previously by our team31. For the membrane feedings, the Hemotek® membrane feeding system (Hemotek® Limited, Great Harwood, UK) was used. The system was kept at 37,5 °C and the reservoir containing 1 mL of the diet was covered with a stretched Parafilm membrane. The Hemotek® feeder was placed on the top of the cage and female mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 30–45 min. When needed, unfed mosquitoes were discarded, and fully engorged females were kept at 26 ± 1 °C, 75% humidity.

Blood standard feedings

CD1 mice (Mus musculus), obtained from the IHMT Animal house, were intraperitoneally anesthetized with ketamine (120 mg/kg Imalgene 1000, Merial, Portugal) and xylazine (16 mg/kg Rompun, Bayer, Portugal). Female mosquitoes fed directly on healthy CD1 mice for 30–45 min, with regular monitoring to verify that mice were anesthetized. When applicable unfed mosquitoes were discarded, and fully engorged mosquitoes were kept at 26 ± 1 °C, 75% humidity.

Bloodmeal appetite

Approximately 35 female mosquitoes with 5 days old were collected from the stock cages (both from the BLOODless diet and the blood mosquito colonies) using a mechanical aspirator and kept inside 500 mL paper cups covered with a mosquito net mesh, without 10% glucose solution overnight.

Mice were anesthetized as described above and female mosquitoes were allowed to feed directly on healthy mice for 30–45 min, with regular monitoring. After the feeding, fully engorged mosquitoes and unfed mosquitoes were both counted, and the feeding rate was calculated.

Dietary preference

Approximately 40 female mosquitoes with 5 days old were collected from the stock cages (both from the BLOODless diet and the blood mosquito colonies) using a proper mechanical aspirator and were kept inside 20*20*20 cm net mesh cages, without 10% glucose solution overnight. On the day of the feeding, the BLOODless diet was prepared as described previously and a few drops of blue food colouring solution were added to it to facilitate its visualization on the females’ midguts. Additionally, a 6-week-old CD1 mice (Mus musculus) was anesthetized as described above. A cardiac puncture was performed when the mouse displayed no muscle reaction in response to different physical stimuli for blood collection. Finally, two Hemotek® reservoirs were offered for 30–45 min simultaneously to the same mosquito cage, one containing the blue coloured BLOODless diet and the other containing mouse blood. After the feeding, mosquitoes were anesthetized for 3 min at − 20 °C and counted.

Life expectancy

Fifteen males and fifteen females from both colonies (Blood and BLOODless diet) were kept in separate net cages and fed with 10% glucose solution ad libitum under optimal insectary conditions (26 ± 1 °C, 75% humidity and a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle). Dead adults were counted and removed daily. Both colonies were maintained at the same temperature, humidity, light cycle conditions and sugar feeding regime. Deaths were registered daily. Life expectancy was evaluated on generations 6, 9 and 38.

Wings size

Five days old adult mosquitoes (males and females) from 4 different generations (F2, F4, F6, F8 and F38) were collected to evaluate their wing size. Mosquitoes were submitted to–20 °C for 5 min. Under a stereoscope, the thorax of each mosquito was gently grasped with forceps and placed ventral side up. Both wings were collected using a scalpel and placed on a clean microscope slide. With the aid of a 20 G needle a drop of Entellan mounting media was added to the borders of the coverslip and the coverslip was slowly lowered onto the wings. The wing length was measured with a stereoscope using a scale.

P. berghei infections

CD1 mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with 107 P. berghei ANKA expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of Hsp70 promotor (P. bergheiHsp70-GFP) parasitized red blood cells. The levels of parasitaemia were measured from blood smears of the mouse tail using Giemsa-stained blood films. When parasitaemia reached 20–40% and exflagellation was visible, mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized as described above, and placed on top of the mosquitoes’ cages (n = 50 females, 5 days old). To ensure consistency and comparability, female mosquitoes from both insectaries fed on the same infected mouse during each feeding session. Female mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 30 min. Unfed mosquitoes were counted and discarded, and fully engorged females were kept at 19–21 °C and 80% humidity for optimal P. berghei development. Midguts were dissected 8 days post-infection and mounted on glass microscope slides for oocyst prevalence and intensity determination. Infections were performed on generations 23, 27 and 38.

Microbiota sequencing

We investigated the taxonomic composition and diversity of the microbial communities associated with midguts and salivary glands of Anopheles mosquitoes fed either on artificial blood free diet (F10 from BLOODless colony) or on standardized bloodmeal (F10 from Blood insectary). Midguts were collected from female and male mosquitoes, and salivary glands were collected from female mosquitoes, under sterile conditions. Tissues were kept on DNA/RNA shield solution at − 20 °C to maintain bacteria diversity. For each meal type and each tissue type, three pools of 20 mosquitoes each (in a total of 18 pooled samples) were used for genomic DNA extraction using a Qiagen QIAamp Fast DNA Tissue Kit according to manufacturer’s protocols. gDNA quality was assessed on a Qubit apparatus by using the Quant-iT™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Supplementary Table S8A). All nucleic acid samples were stored at 4 °C and sent for 16S Metagenomic Illumina Sequencing in POLO GGB. A negative control containing no gDNA and a positive control consisting of a known microbial community (ZymoBIOMICS™Microbial Community Standard II) was evaluated as well. The libraries were prepared in accordance with the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Guide (Part # 15,044,223 Rev. B) and the Nextera XT Index Kit. The V3 and V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene of DNA samples were amplified using specific primers and dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters were attached. The resulting libraries were validated using the Fragment Analyzer (High Sensitivity Small Fragment Analysis Kit) to check size distribution. Concentration of library samples was defined based on the Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer quantification and average library size. Indexed DNA libraries were normalized to 4 nM and then pooled in equal volumes. The pool was loaded at a concentration of 10 pM onto an Illumina Flowcell standard with 12,5 pM of Phix control. The samples were then sequenced using the Illumina V2/chemistry in Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 250 bp paired end run).

Whole genome sequencing

With the objective of characterizing genetic changes between the control and BLOODless diet samples, we performed whole genome sequencing on pooled 5 days-old females (n = 10 from F10) from each dietary group and for each of the three replicates. Genomic DNA was extracted from single mosquitoes using a Qiagen QIAamp Fast DNA Tissue Kit according to manufacturer’s protocols. The quality and quantity of the DNA was assessed through a Qubit apparatus by using the Quant-iT™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Supplementary Table S8B). Individual gDNA samples were stored at 4 °C and a pool of normalized gDNA from 10 females was analysed for each replicate and dietary group. The 6 pooled samples of gDNA were sent to POLO GGB for Illumina 150 bp paired-end sequencing. The DNA library was prepared in accordance with the Illumina DNA Prep Library Prep Kit Reference Guide (Document #1000000025416v09, June 2020) for Illumina Paired-End Indexed Sequencing. Genomic DNA was tagged and fragmented using the Bead-Linked Transposomes. The tagmented DNA was then amplified via a limited-cycle PCR program to add index 1 (i7) and index 2 (i5) and sequences, as well as common adapters, required for cluster generation and sequencing. The resulting libraries were validated using the Fragment Analyzer (High Sensitivity Small Fragment Analysis Kit) to check size distribution. The libraries for each sample were normalized and the pooled library was loaded on a NextSeq 550 Flowcell High Output.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

Fitness, behavioral and infectivity experiments

The effect of type of meal (BLOODless versus Blood) on each of the quantitative variables related to Fitness, behavior and infectivity was analyzed with ANCOVA to control for generation (covariate) and sex. Assumptions of ANCOVA were tested (homogeneity of regression slopes between covariate and grouping variable, normality of residuals, homogeneity of variances).

Microbiota analysis

Each sequenced sample was trimmed for adapter sequences during demultiplexing with bcl2fastq v2.20.0.422 software. Quality control was done using FastQC tool32. Trimmomatic v0.36 software33 was used with default settings to check and remove low quality bases as well as filter out further adapter/primer sequences. Sequenced paired-end reads were merged to reconstruct the original full-length 16S amplicons with the vsearch join-pairs plugin available in the QIIME2 environment. All amplicons with sequence similarity higher than 97% were grouped together and a representative was chosen as input for making the taxonomy annotation and building the OTU table. The dereplication and clustering steps were performed using the plugins: vsearch dereplicate-sequences and vsearch cluster-features-de-novo. The occurrence of chimera sequences was identified using the plugin vsearch uchime-de novo. The detected chimera sequences were then used to further filter the data set and the OTU table (plugins: feature-table filter-seqs and feature-table filter-features). To assign the taxonomy to each OTU, a classifier was trained through machine learning, using the plugin qiime feature-classifier fit-classifier-naive-bayes. The classifier was then applied to the 16S SILVA database to select only the V3-V4 regions of the entire 16S sequence. The amplicon sequences were then matched with the refined database and the taxonomy assigned to each OTU. A further filtering step was performed to remove the mitochondrial sequences. The core diversity analyses were performed after rarefying the samples at the same number of reads, corresponding to the minimum number of reads observed among all samples (i.e., 400,000 reads). Negative and positive controls have been excluded in core diversity analysis. The variability within samples (alpha diversity) was analysed with the following metrics: number of OTUs per sample, Shannon’s diversity index (a quantitative measure of community richness) and Simpson’s Index (probability that two individuals randomly selected from a sample will belong to the same taxa). Beta-diversity was quantified using Bray–Curtis distance. These distances were used to perform PCoA and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) to analyze the difference between type of meal, sex and type of tissue.

Whole genome sequencing analysis

The analyses followed the pipelines PoPoolation v. 1.2.2 and PoPoolation2 v. 1.2.0134,35, developed for pooled sequencing. An initial step of quality filter was performed with trim-fastq.pl script of the PoPoolation package. Paired-end reads were mapped to the reference genome of Anopheles stephensi (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_013141755.1/) using bowtie2 with the sensitive option. Duplicates were removed with PICARD and low-quality alignments and unmapped reads were removed with samtools view. A pileup file for each sample was generated with samtools mpileup, followed by indel filtering. This file was then converted to sync format for Popoolation2. For each variable nucleotide site, we calculated the allele frequency and nucleotide diversity in each sample, and the pairwise FST differentiation between the samples (populations) using fst-sliding.pl from PoPoolation2 package. To find candidate SNPs for adaptation to the new dietary condition, we first detected allele frequency changes between the control and the artificial diet, consistent across the three biological replicates, using the Cochran-Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test, as implemented in cmh-test.pl from Popoolation2. The SNPs with lower p values in the CMH test (log10p > 10), were retained. Since a decrease in a minor allele is more likely due to drift, we additionally filtered the SNPs to consider those who had initially the same minor allele in the control and that increased in frequency in the artificial diet, for all three replicates. To find significant hits with proteins, we searched the SNP regions (considering 200-bp upstream and downstream of the candidate SNP) on protein database nr from NCBI (version) using blastx with an e-value cutoff of 1e-10). Output_blast Gene Ontology categories were obtained using Blast2Go version 6.0.336.

Data availability

Scripts and pipelines used in the analyses are available at: https://github.com/seabrasg/Anopheles_diet. The sequences generated and analyzed during this study have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the submission code SUB14555731 (WGS) and reference PRJNA1130028 (microbiota). The input data for R script is available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12188601).

References

Dame, D. A., Curtis, C. F., Benedict, M. Q., Robinson, A. S. & Knols, B. G. J. Historical applications of induced sterilisation in field populations of mosquitoes. Malar. J. 8(Suppl2), S2 (2009).

Lacroix, R. et al. Open field release of genetically engineered sterile male Aedes aegypti in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 7, e42771 (2012).

Yen, P. S. & Failloux, A. B. A review: Wolbachia-based population replacement for mosquito control shares common points with genetically modified control approaches. Pathogens 9, 404 (2020).

Chung, H. N. et al. Toward implementation of mosquito sterile insect technique: The effect of storage conditions on survival of male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) during transport. J. Insect Sci. 18, 2 (2018).

Gonzales, K. K. & Hansen, I. A. Artificial diets for mosquitoes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 1267 (2016).

Phasomkusolsil, S. et al. Maintenance of mosquito vectors: Effects of blood source on feeding, survival, fecundity, and egg hatching rates. J. Vector Ecol. 38, 38–45 (2013).

Marques, J. et al. Fresh-blood-free diet for rearing malaria mosquito vectors. Sci. Rep. 8, 17807 (2018).

Pérez-Ramos, D. W., Ramos, M. M., Payne, K. C., Giordano, B. V. & Caragata, E. P. Collection time, location, and mosquito species have distinct impacts on the mosquito microbiota. Front. Trop. Diseases 3, 896289 (2022).

Saab, S. A. et al. The environment and species affect gut bacteria composition in laboratory co-cultured Anopheles gambiae and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60075-6 (2020).

Sarma, D. K. et al. Influence of host blood meal source on gut microbiota of wild caught Aedes Aegypti, a dominant Arboviral disease vector. Microorganisms 10, 332 (2022).

Weiss, B. & Aksoy, S. Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends Parasitol. 27, 514–522 (2011).

Diallo, M. et al. Evaluation and optimization of membrane feeding compared to direct feeding as an assay for infectivity. Malaria J. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-248 (2008).

Melgarejo-Colmenares, K., María Cardo, V. & Vezzani, D. Blood feeding habits of mosquitoes: Hardly a bite in South America. Parasitol Res 1, 3 (2022).

Sawadogo, S. P. et al. Effects of age and size on Anopheles gambiae s.s. male mosquito mating success. J. Med. Entomol. 50, 285–293 (2013).

Mwangangi, J. M. et al. Beier JC Relationships between body size of Anopheles mosquitoes and Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite rates along the Kenya coast. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 20, 390–394 (2004).

Lorenz, C., Marques, T. C., Sallum, M. A. M. & Suesdek, L. Altitudinal population structure and microevolution of the malaria vector Anopheles cruzii (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit. Vectors 7, 1–12 (2014).

Enrique, R. et al. Climate associated size and shape changes in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) populations from Thailand. Infect. Genet. Evolut. 10, 580–585 (2010).

Aytekin, S., Aytekin, A. M. & Alten, B. Effect of different larval rearing temperatures on the productivity (R o ) and morphology of the malaria vector Anopheles superpictus Grassi (Diptera: Culicidae) using geometric morphometrics. J. Vector Ecol. 34, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7134.2009.00005.x (2009).

Ngowo, H. S., Hape, E. E., Matthiopoulos, J., Ferguson, H. M. & Okumu, F. O. Fitness characteristics of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus during an attempted laboratory colonization. Malar J 20, 1–31 (2021).

Barreaux, A. M. G., Stone, C. M., Barreaux, P. & Koella, J. C. The relationship between size and longevity of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae (s.s.) depends on the larval environment. Parasit. Vectors 11, 1–9 (2018).

Linenberg, I., Christophides, G. K. & Gendrin, M. Larval diet affects mosquito development and permissiveness to plasmodium infection. Sci Rep 6, 38230 (2016).

Carvajal-Lago, L., Ruiz-López, J., Figuerola, J. & Martínez-De La Puente, J. Implications of diet on mosquito life history traits and pathogen transmission. Environ. Res. 195, 110893 (2021).

Da, D. F. et al. Experimental study of the relationship between plasmodium gametocyte density and infection success in mosquitoes; Implications for the evaluation of malaria transmission-reducing interventions. Exp. Parasitol. 149, 74–83 (2015).

Graumans, W., Jacobs, E., Bousema, T. & Sinnis, P. When is a plasmodium-infected mosquito an infectious mosquito?. Trends Parasitol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.05.011 (2020).

Kanatani, S., Stiffler, D., Bousema, T., Yenokyan, G. & Sinnis, P. Revisiting the Plasmodium sporozoite inoculum and elucidating the efficiency with which malaria parasites progress through the mosquito. Nat. Commun. 2024(15), 1–13 (2024).

Sinden, R. E. et al. Progression of plasmodium berghei through Anopheles stephensi is density-dependent. PLoS Pathog. 3, e195 (2007).

Habtewold, T. et al. Plasmodium oocysts respond with dormancy to crowding and nutritional stress. Sci Rep 11, 3090 (2021).

Medley, G. F. et al. Heterogeneity in patterns of malarial oocyst infections in the mosquito vector. Parasitology 106, 441–449 (1993).

Singh, A. et al. The dynamic gut microbiota of zoophilic members of the Anopheles gambiae gambiae complex (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep. 12, 1495 (2022).

Matos, M. et al. History, chance and selection during phenotypic and genomic experimental evolution: Replaying the tape of life at different levels. Front. Genet. 6, 71. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2015.00071 (2015).

Marques, J., Cardoso, J. C. R., Félix, R. C., Power, D. M. & Silveira, H. A blood-free diet to rear anopheline mosquitoes. J. Vis. Exp. 155, e60144 (2020).

Andrews S. Babraham Bioinformatics—FastQC A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2020).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Genome analysis Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Kofler, R., Pandey, R. V. & Schlötterer, C. PoPoolation2: Identifying differentiation between populations using sequencing of pooled DNA samples (Pool-Seq). Bioinformatics 27, 3435–3436 (2011).

Kofler, R. et al. PoPoolation: A toolbox for population genetic analysis of next generation sequencing data from pooled individuals. PLoS One 6, e15925 (2011).

Gotz, S. et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res 36, 3420–3435 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lidia M. D. Gonçalves (Principal Investigator at the Faculdade de Farmácia from Universidade de Lisboa) for technical support. This work was financed by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia Aga-Khan De-velopment Network (FCT-AGAKHAN/541725581/2019) and has received resources funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agree-ments No 731060 (Infravec2). JM, SGS, ACA and HS are supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT Portugal) for funds to GHTM/IHMT-NOVA (GHTM-UID/04413/2020). JM is recipient of a contract by FCT (DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECIND/00450/2017/CP1415/CT0001). SGS was funded by FCT, Portugal, through contrato-programa 1567 (https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECINST/00 102/2018/CP1567/CT0040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM and HS formulated the BLOODless diet, conceived and designed the study. SGS provided valuable input for the microbiome and whole genome sequencing evaluation. JM, IA, JG and ACA maintained both mosquito colonies used throughout this work. JM and IA implemented the BLOODless insectary and performed the experimental assays. JG assisted on tissue dissec-tions. SGS performed all the statistical analysis, bioinformatic analysis and constructed the final graphs. JM, SGS and HS co-wrote the manuscript and all the authors reviewed and approved its final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Joana Marques and Henrique Silveira are inventors of the patented BLOODless diet (PCT/IB2019/052967, WO/2019/198013 and US2021030025A1), owned by Universidade Nova de Lisboa and Universidade do Algarve. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marques, J., Seabra, S.G., Almeida, I. et al. Long-term blood-free rearing of Anopheles mosquitoes with no effect on fitness, Plasmodium infectivity nor microbiota composition. Sci Rep 14, 19473 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70090-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70090-6