Abstract

Some special manufacturing fields such as aerospace may encounter mixed production of multiple research and development projects and multiple batch production projects. Under these special production conditions resource conflicts are more severe, resulting in uncertain operating times that are difficult to predict. In addition, a single project may have tens of thousands of supporting products, making it difficult to effectively control the total construction process. To address these challenges this paper proposes new methods. A model, EMA-DCPM (dynamic critical path method) incorporating attention mechanisms in Enterprise Resource Planning and Mechanical Engineering Society) has been proposed. This model predicts product job time through machine learning methods and discovers the predictive advantage of the attention mechanism through data comparison. The CPM control algorithm was improved to enhance its robustness and an efficient modeling method, “5+X” was proposed. This new method is suitable for mixed line planning management in sophisticated manufacturing projects and has value for practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation and research gap

Owing to rapid changes in market demand, many manufacturing firms encounter multi-project and multivariate operations and variable-batch mixed-line production. The term multiproject refers to the production tasks of multiple projects simultaneously undertaken by enterprises. The term multivariate refers to a large number of product items. A variable batch means that an item has an unfixed production quantity. A mixed line refers to the simultaneous online production of multiple projects. This complicated task situation introduces great challenges in scheduling algorithm research.

Once manufacturing enterprises have the above production characteristics, they will often encounter problems such as multiproject resource preemption, overproduction, poor turnover capacity, and delayed planning. These problems will greatly affect the production efficiency and reduce the business ability of enterprises.

In some special industries such as aerospace manufacturing there are situations where multiple research and development projects and multiple batch production projects are simultaneously produced online. Owing to rigid planning and limited resources it is common for multiple project tasks to be produced in a centralized manner based on the same resource. Tasks interact with each other and resources change frequently. All of these factors lead to significant fluctuations in product operation time. Owing to the unpredictability of future homework schedules, there is also a risk of inaccurate planning and scheduling. In addition, the project is very complex. A product plan consisting of a single project can reach tens of thousands of items and the management of related plans is very difficult, particularly achieving dynamic control of plans by relying on manual labor.

Contribution

To solve such complex problems, we need to pay attention to developments in computer science and management science and effectively combine them. On the one hand, we need to solve the issue of job time prediction in a complex production environment. Accurate product processing time directly affects the final result of the algorithm. However, obtaining an accurate product processing time is very difficult and changes with the production environment. On the other hand, we need to provide dynamic control algorithms to realize dynamic control over the total duration of complex projects and optimize production plans. In complex environments managers need to focus continuously on controlling planned time and achieving better control results with minimal cost. The most prominent contradiction in project management is in timely performance, so time is the key. If there are errors in input time, these errors will be directly reflected in the control results.

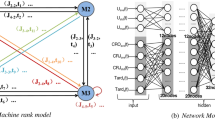

In this paper, a dynamic optimization CPM model in an ERP/MES system with an attention mechanism (EMA-DCPM) is designed based on machine learning and CPM technology. This model can accurately predict the operation time of variable batch products and realize dynamic control of the total duration of complex projects. This algorithm provides a feasible solution for production planning control in complex manufacturing environments. Our proposed method consists of two modules. The first is the operation time prediction module, and the second is the dynamic optimization control module based on CPM technology.

Applying this solution, it is possible to achieve mixed line operation time prediction in the aerospace field, thereby improving the accuracy of future plans. During nonfixed production operating time is relatively fixed. However, during mixed production there is significant uncertainty in operating time and accurate data are difficult to obtain. In this scheme, the prediction of product job time enriches the product job time database for managers, improves accuracy, and has great benefits for subsequent planning and scheduling. In addition, the method provides a set of “6n+5” methods that can quickly construct complex aerospace project planning models. Managers can use the “6n+5” method to quickly complete modeling and then use an improved CPM model to dynamically control the plan, achieving dynamic control of complex aerospace project plans and ensuring the completion of delivery tasks according to the plan.

Related work

An increasing number of enterprises have realized that intelligent scheduling is the fundamental way for enterprises to efficiently organize production. Current intelligent scheduling algorithms can be divided into two research directions.

One direction focuses on continuing to optimize heuristic algorithms to solve practical production problems or improve the efficiency of finding the optimal solution. This more traditional scheduling problem solution is mainly based on the traditional heuristic algorithm represented by ant colony optimization algorithms. In recent years, scholars have paid more attention to the complexity of practical and ever-changing production processes. A nonsingle objective solution based on a genetic algorithm was proposed by Chen1. Their goal was to optimize power consumption and minimize production cycles. A new architecture combining pattern matching with a genetic algorithm was proposed by Liu2. This algorithm can minimize latency to the greatest extent possible. Lu proposed a genetic algorithm-based method for modeling three-dimensional problems through one-dimensional solutions to solve nonpulsating and nonunit manufacturing workshop scheduling problems3. A locally enhanced particle swarm optimization compound algorithm was used by Marichelvam4 to solve a multilayer mixed transportation scheduling problem. For a no-waiting scheduling problem, Zhao incorporated the advantages of a population mechanism into the particle swarm optimization algorithm, effectively integrating the direct advantages of the algorithm5. A two-level particle swarm optimization enhancement algorithm was proposed by Zarrouk6. The upper layer is used to process the mapping of operations to equipment and the lower layer is used to process the sequence of equipment operations. A new complex ant colony optimization algorithm solution based on crossover and mutation mechanisms was designed by Engin7. To address specific task scheduling issues an algorithm that combines cuckoo search techniques with ant colony operation techniques was proposed by Zhang8. Elmi proposed a solution method for ant colony optimization of robot tasks9. There are many studies of such scheduling algorithms10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In recent years, these studies have increasingly focused on the complexity of production plan management. Plan management systems are the core of enterprise management. Most production and business activities are closely carried out around the enterprise planning system. Some investigators have focused on the multilayer structure of planning systems, considering the linkages between different levels of planning systems. At the same time, researchers have further explored multi-objective optimization, taking into account multiple factors such as energy consumption, inventory, materials, carbon emissions20,21,22, costs and conducting multiobjective coordination. Some suitable algorithms have been proposed.

The other research direction focuses on the use of machine learning algorithms and fully exploits their advantages in terms of efficiency and accuracy. Sha proposed a priority-based parallel reinforcement learning task scheduling strategy verifying the high convergence of Q-learning23. Zhang replaced automatic learning PDR with end-to-end deep reinforcement learning24. Swarup proposed a double-depth Q learning algorithm using a target network and relay technology25. Luo extracted seven general state features to represent the rescheduled production state and used deep Q learning for training26. Silva used the concept of reinforcement learning to enable agents to interact with other agents and environments27. Park proposed an RL strategy based on near-end strategy optimization trained in an end-to-end manner28. In recent years, deep learning has been widely used to solve shop scheduling issues29,30.

These above findings were statistically analyzed, as presented in Table 1. These statistics focus on five main issues. The first is how to define product processing time in the algorithm. The second is whether to perform preprocessing after defining the product processing time in the algorithm. The third is whether the algorithm considers control of project planning. The fourth is whether the algorithm considers the mixed production environment. The fifth question is whether the algorithm is validated using actual production data.

Table 1 shows that existing research on these scheduling algorithms focuses on the algorithm itself but weakens the processing of product processing time. The commonly used methods for processing product processing time include fixed values, fuzzy values, and random numbers, and there is little preprocessing. Time is an important input for scheduling algorithms and if this input is inaccurate and not real-time the accuracy of the algorithm’s output will be affected. Moreover, in mixed-line production product processing time is generally not a fixed value. In addition, most algorithms focus mainly on workshop production and rarely pay attention to project planning control. For group enterprises workshop plan management is a process and project plan management is a result, and research on project plan management models is very important.

In this era of high-speed information technology some enterprises have acquired knowledge of the actual operation time for some stable products using ERP and MES systems. However, it is difficult to obtain operation times for multi-variety and variable-batch mixed-line products. With full consideration of production efficiency, mixed-line status, seasonal changes and other factors, such operation times are similar to those of the stock index, which cannot be directly collected or simply predicted31,32,33. In the actual project plan management process the most important aspect is advance determination of future project plans. We not only care about the production time of the previous products but also want to know the possible production time of future products. The prediction of production operation time is more accurate and prediction of the project plan is more instructive.

We believe that if real-task-time management and project management technology are combined and the former is used as the input of the latter, the relevant management ability of an enterprise will be greatly improved. CPM technology is an aspect of operational research and is a method that is used for project planning and control. It is used to form specific schemes for project construction through time parameter calculations, critical route analyses and other means34,35,36,37,38,39. Traditional CPM technology focuses on predictions of the total construction period but lacks dynamic optimization features and is difficult to use for complex project control. Therefore, in this paper we optimize CPM technology to meet the firm requirements of total construction period target control (Fig. 1).

This paper summarizes the most influential research regarding commonly used planning and scheduling models over the past decade, as shown in Fig. 1. Figure shows that over the past decade the number of important new achievements in commonly used scheduling algorithm models such as the genetic algorithm, tabu search algorithm, particle swarm algorithm, ant colony algorithm, estimation of distribution algorithm, etc., has shown a downward trend. However, in the past 3–4 years, relevant achievements have still been released annually. There were few new advances in the CPM algorithm between 2016 and 2021 but in the past three years, some investigators have focused on this traditional algorithm. The results for machine learning algorithms show a downward trend from 2015 to 2020 but have developed rapidly since 2021. Many are studying the advantages of machine learning, such as self-learning and repeated trial and error, for planning and scheduling decisions. Therefore, this paper considers the use of machine learning models and CPM algorithms for complex plan management in aerospace manufacturing since there are few studies on these scheduling algorithms that specifically target aerospace manufacturing projects.

In summary, this paper focuses on four aspects. The first is to focus on product homework time collection, preprocessing, and accurate prediction, not previously covered. The second is to use machine learning methods to improve the accuracy of product operation time and select appropriate models through comparative methods. The third is to focus on the project plan control model, overlooked in previous papers, and improve it based on the CPM model. Currently, researchers tend to emphasize the concept of dynamic scheduling in dynamic rescheduling40 and event management41. These findings inspire us to perform dynamic feedback optimization on traditional CPM models. The fourth is to maximize the use of actual product operation time, without the need for fictitious time, and improve the prospects for engineering applications.

Methods

EMA-DCPM algorithm

Figure 2 shows the EMA-DCPM algorithm structure. The EM represents the ERP/MES system, a represents the attention mechanism, and the DCPM represents the dynamic optimization CPM model.

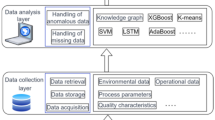

The input of this algorithm model is the product processing data recorded in the ERP/MES system. The production time data are divided into part processing time data and operation processing time data. The part production time data can be used as direct input into the CPM model. To obtain part of the processing time data and operation processing time data, a document containing product task information was created in the ERP/MES system.

These documents will be used for product circulation within the workshop and for external circulation within the workshop. These electronic documents pay special attention to external circulation of the workshop and produce a QR code before starting external circulation of the workshop. Each workshop is equipped with scanning equipment. By scanning the QR code, the electronic document records the handover data for the product. Through the handover of data, the paper obtained a large amount of homework time data for task documents. If the task involves a pulsating production line these operation time data are relatively fixed. However, during mixed production these job time data fluctuate greatly.

The main task of this work is to predict operating time data for these large fluctuations and obtain the future operating time for a certain batch of products. These homework time data are time series vectors. Possible methods for temporal vector prediction include multilayer perceptron (MLP), long short-term memory (LSTM), and attention mechanism (AM). Before the experiment, AM and a 1 × 1 convolutional layer after the global average pooling layer are used, the fully connected layer is rearranged, and dimension reduction is effectively avoided. Both LSTM and MLP may lose important information leading to convergence difficulties. This will be verified in future experiments. Before the experiment, it is necessary to preprocess the product operation time as detailed in Sect “Data acquisition” and Sect “Data preprocessing”.

One of the advantages of the time prediction model used by artificial intelligence algorithms is that it can obtain real-time and more accurate production time data over the passage of time. We can use these data to predict and control the whole project plan.

The lower half of Fig. 1 shows the DCPM model. The upper part of the EMA-DCPM model completes the time collection and establishes the processing operation time database. This database will be associated with the DCPM model to achieve precise control of the project. Sect “Dynamic optimization CPM model” provides a detailed introduction to the DCPM model. The main data included in the model are shown in Table 2.

Data acquisition

The product production project of an enterprise has the characteristics of a tree structure. This type of product is composed of multiple parts or components. The components of a product are also composed of parts. This composition process can be referred to as a process, as shown in Fig. 3.

We need to distinguish between obtaining the operation time of the finished parts and the operation time of the process itself. Generally, the production of a part requires 10–20 processes. In a true production process the order of magnitude of the actual process operation time is far greater than that of the parts. Most enterprises can obtain only the actual operation time of parts but cannot obtain the process operation time. To obtain the operation time of a specific process we decompose the part task list into a part collaboration operation task list. By utilizing the collaborative process task list, we can facilitate product handover in the collaborative process in a similar manner to the product handover achieved through infrared radio frequency scanning technology. Through this handover process we can obtain the actual operation time of the heat treatment process for all products of an enterprise over the past 2 years. This process is shown in Fig. 4. Owing to the wide variety of heat treatment products and different product batches, more than 40,000 items of heat treatment data are actually collected.

A collaboration task in the collaboration task list is expressed as \(\varphi \) (Formula (1)). \(\gamma \) is the product name, \(\alpha \) is a special number that can distinguish products, \(\mu \) is the collaboration task number, \(\beta \) is the product category, \(x\) is the task start time, \(y\) is the task end time, \(z\) is the product quantity, \(\theta \) is the type of heat treatment (such as quenching or tempering), \({a}_{1}\) is the name of the resource occupied by the task, \({a}_{2}\) is the resource production capacity, and \({a}_{3}\) is the resource operation efficiency:

\(\beta \) and \(\theta \) are used to extract data from the same heat treatment process for the same product. Through this method we obtain real-time processing data of the same heat treatment process for the same product. During this process we clean the null data and incomplete data and retain thousands of data points. These data were used for subsequent data prediction and analysis.

Data preprocessing

Here, the collaborative task data are transformed into a single product processing time vector using Formulas (2) and (3). This time vector is \(\psi \), Ҩ is the time sequence, and ꞃ is the single product operation time of the current time:

The advantage of this design is improvement in convergence of the calculation. At the same time, it is convenient to predict the operation time of different batches of products in the same heat treatment process of unknown similar products in the future.

Through the data acquisition and pretreatment methods in Sect “Data acquisition” and Sect “Data preprocessing” the actual operation time data for the quenching process are obtained. There are 374 pieces of data in this dataset and the data distribution is shown in Fig. 4. Other types of heat treatment operation time data can also be processed in this way. However, in this paper we describe only one type of data in detail. Figure 5 shows that the actual collected heat treatment operation time significantly fluctuated. This is because in actual mixed production activities there may be resource conflicts between products. Product processing is affected by other product processing plans resulting in longer waiting times and turnaround times for product processing. Owing to the collection of such actual data and the instability of the mixed offline operation time, the importance of time prediction is considered.

These data represent the operation time for a single piece of a certain product to complete quenching during 2020 to 2022. Although the product type is the same and the heat treatment process is the same due to different product batches as shown in Fig. 5, different mixed batch tasks and different time intervals, the actual operation time changes irregularly. The distribution values for the high-latitude change data on the left side of the figure are mostly greater than the data distribution values on the right side, as shown in Fig. 6.

The operation time data group covers 2021 and 2022. We compare the two sets of annual data, as shown in Fig. 6. Through this comparison it is easier to see that after the production capacity of the enterprise is improved in 2022 there is a decrease in most working time data. Enterprises are constantly evolving and dynamic. Through research on these subjects the company invested in using two CNC heat treatment devices in 2022, expanding its heat treatment capabilities. The changes in corporate capabilities are indirectly shown in Fig. 6. This is why it is necessary to predict future operation time using previous operation time data. These factors should be considered in the operation time data used for project plan management.

We find that there is a certain relationship between the operation time and the quarter. The operating hours of enterprises increase significantly in the 2nd–4th quarters of 2021 and 2022. This is because in the 2nd–4th quarters the enterprise is operating at full capacity. Under the influence of a comprehensive production environment products cannot be produced according to the standard operation time. Next, we use machine learning technology to predict the subsequent product operation time.

Dynamic optimization CPM model

An increasing number of enterprises have adopted CPM technology to plan and manage complex projects. CPM technology uses logical relationships between tasks and known operation times to calculate the time parameters, thus predicting the total duration of a project. A CPM model is a network graph path planning model used in operational research. To better integrate a predicted job time with a CPM model, we define a task in the CPM model as \(\sigma \), as shown in Formula (4). \({n}_{i}\) is the front node of the task, \({n}_{j}\) is the rear node of the task, \({R}_{ij}\) is the total float, \(t\) is the operation time of task \(\sigma \), \({K}_{i}\) is the node immediately before the task, \({k}_{j}\) is the node immediately after the task, and \(o\) is the completion status of the task. \({R}_{ij}\) is the difference between the latest completion time and the earliest completion time. See Eq. (5) for details.

In this paper, we innovatively adopt an algorithm that can dynamically optimize the CPM model. During actual project operation we need to track the total duration according to the actual completion of various tasks in the project. By comparing the current total construction period with the target total construction period, companies can determine whether a project is delayed. Therefore, we consider the work completion status in \(\sigma \). In addition, according to CPM theory the task of \({R}_{ij}\) = 0 is the key work. Reducing the working time of the key work can affect the total construction period. \({R}_{ij}\)= 0 is also an important tag in \(\sigma \).

The core of the CPM optimization model is to compress the operation time of tasks when \({R}_{ij}\) = 0. When compressing the job time, we suggest compressing according to the relative value and setting a compression threshold. In addition, we store each key work found in an array. When compressing the key work, priority is given to key work with a small sequence number and uncompleted work. The optimized CPM model logic architecture is shown in Fig. 7.

\({R}_{ij}\) is obtained with Formula (5). The project consists of multiple σ tasks. Based on the logical relationship of σ tasks, traversing all σ tasks yields the total duration. The design of Fig. 6 utilizes the significance of the key task (the task of \({R}_{ij}\) = 0). Once the duration of these tasks is compressed, the total duration is also correspondingly shortened. Only by shortening the overall construction period can planning arrangements be optimized.

The algorithm program uses the Python language and the NetworkX toolkit. A topological sequence function is used for programming. The project plan data table is imported and the task time parameter data and directed graph are output, employing the critical path method for determining the total project duration.

Experimental evaluation and discussion

Operation time prediction

As shown in Fig. 3, the operation time data exhibit large fluctuations. This is one of the significant characteristics of product processing in the process of variable mixed batch production.

To select appropriate algorithms for operation time prediction we adopt three different algorithms: multilayer perceptron (MLP), long short-term memory (LSTM) and an attention mechanism. These methods are often used for training and learning time series data. Through comparative experiments we show that the attention mechanism has advantages over other models when dealing with actual product operation time data.

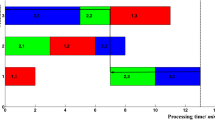

Through calculation, we obtain the prediction results of different algorithms and the process of calculation convergence, as shown in Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11.

Figure 11 shows that the attention mechanism has obvious advantages over the MLP and LSTM in predicting the operation time of multivariate and variable mixed batch production. The main reason is that the attention mechanism can focus on relevant information and ignore irrelevant information. The attention mechanism directly establishes dependency between the input and output, enhances the degree of parallelism, and greatly improves the running speed. It overcomes some limitations of the MLP and LSTM. It can extract the characteristics of data with large fluctuations, capture remote information well, reduce the hierarchy depth and effectively improve accuracy.

We compare data from the first week of operation in 2023 predicted by the three models, the data derived using the traditional mean method, and the actual data collected, as shown in Table 3.

The attention mechanism selected in this paper has more advantages and higher accuracy than those of the other two algorithms in the prediction of operation time. Enterprises commonly use the average method to calculate homework time. According to these examples the average result is 3.7 days. The predicted value of the artificial intelligence model is 1.02 days, and the true value is 0.92 days. The average value has an error of 302% compared with the true value. The error between the predicted value from the artificial intelligence model and the actual value is 10.9%. The difference between the traditional method data and the actual data is approximately 3 days. These different data affect the final result of the scheduling algorithm, resulting in inaccurate project schedule forecasting. In other words, the traditional calculation method cannot be used for complex production environment scheduling of mixed line and variable batch production.

From the perspective of algorithm computational efficiency, the core of the attention mechanism lies in calculating the similarity between the query (Q), key (K), and value (V) and then obtaining the attention weight for each position. Therefore, in addition to the time complexity of Softmax operations, weighted summation, and other steps, the complexity of the attention mechanism also requires the calculation of the time complexity of Q, K, and V. Due to the increased complexity the task time prediction calculation time of the attention mechanism is longer than those of the first two algorithms. However, the prediction of the product operation time has little dependence on the computation time and focuses more on accuracy. Therefore, the attention mechanism algorithm is more suitable for job time prediction than the first two algorithms are.

Most of the production data are temporal vector data. These findings indicate that people can utilize the powerful fitting and prediction capabilities of machine learning to effectively process and utilize data and implement precise control over production management. We find that as long as production enterprises establish a production information system, a large amount of product production time from the production site can be collected. If these time data samples reach a certain magnitude and need to be used as important input data for planning, scheduling, cost management, etc., the AM model mentioned in the paper can be used for prediction processing to improve accuracy.

The prediction of product operation time is a new direction for planning and scheduling research. There are almost no relevant research results in current papers. This paper is based on a theoretical analysis of the AM optimal algorithm, which we validate above. In addition, reported in the medical field42 that the AM algorithm has advantages over other algorithms in predicting long-term continuous time series. The results of this interdisciplinary study indirectly support our analysis.

Dynamic optimization CPM model validation

Using the new calculation model we quickly obtain digraphs before and after planning. To verify the calculation model we analyze the classical calculation example. These model operation results are shown in Fig. 12.

The black lines represent the tasks used for testing and the numbers on the lines represent the assignment times for the tasks. The red line represents the process series with the longest path which can act as the critical path method and obtain the total duration.

The above figure shows that the total construction period is delayed because the duration of the (1, 3) key task is changed. The initialization duration is 51 days. After the task status changed, the duration changed to 53 days. After the model determines that the total construction period is delayed, the duration of the (5, 6) key task that has not started will be compressed until the original total construction period target is met. The optimized duration is the same as the expected duration. In addition, compressed critical work affects the results of the critical path and even generates new critical paths.

To verify the effectiveness of the model, we use random datasets for testing. The test results are shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 13 shows that the total construction period target obtained from the random dataset is 59 days. When importing random actual task data the total duration is 61 days thus it is predicted that the project will be delayed by 2 days. After optimization of the model the total construction period is 56.4 days, and the project is completed 2.6 days ahead of schedule. The optimization model achieves the project control objectives. Because the key operation time is compressed to a certain extent, the project may be completed ahead of schedule.

The optimized results indicate that the algorithm can achieve dynamic control and adjust the duration, and that the task operation time on the critical path is compressed within a controllable range. Furthermore, we find that the original critical path may change and that a new critical path will be generated when the critical path is compressed. The new critical path does not affect the dynamic control of the total duration.

The EMA-DCPM model meets design expectations and can dynamically control project schedule objectives. The EMA-DCPM model can be used for projects with high planning rigidity; that is, the plan can only be advanced but not postponed. The main reason for improvement in the accuracy of the plan is that an attention mechanism is used to predict the operation time of the process. In addition, the experiment compares two different project situations: maintaining the critical path and changing the critical path. These results verify that the improved CPM algorithm is robust.

Before the CPM model is used for calculations it is necessary to logically process all the task contents and clarify the relationships between each task. For a complex aerospace manufacturing project, expressing tens of thousands of supporting products through logical relationships is a considerable workload. This paper proposes a new modeling method, the “6n+5” model, to maximize the advantages of the CPM algorithm. The “6n+5” model is shown in Fig. 14.

The “6n+5” model divides complex aerospace projects into final assembly and component assembly processes, where n represents the n segments of the aerospace project and where 6n+5 is the final number of nodes deduced. During the assembly process a complete set of parts is formed through the configuration of eight nodes. As defined in CPM technology, two nodes represent work content and arrow lines represent\the logical relationships between works. The paper modularizes each section based on the characteristics of the aerospace project. If the aerospace project consists of eight sections, n equals 8, and the task model has 53 nodes (6 * 8+5=53) and 52 task sets. Each task set contains hundreds of parallel component tasks. The advantage of modeling in this way is that only CPM calculations are performed on the task set. The planned time calculated by the CPM for a task set can be replicated in parallel tasks in each task set. If the “6n+5” modeling method is not used, the number of nodes will reach 8713, and memory usage will increase by 164 times. Therefore, when performing CPM calculations the “6n+5” model proposed in the paper has greatly improved computational efficiency. Owing to the high computational efficiency of CPM there is not much difference in computation time between models with dozens of nodes and models with thousands of nodes. Therefore, we need to compare the modeling cycles before computation. The construction of the model requires manual completion. When the “6n+5” model is not used, managers need 2–3 months to complete the project logic relationship expression for eight segment structures. Through the “6n+5” model, managers need only 2 weeks to complete the construction of project logic relationships, greatly improving the efficiency of model construction.

Conclusions

Product operation time is the foundation of scheduling algorithms and affects their output results. This paper examined product operation time prediction using machine learning, using the fitting advantages of machine learning to better solve the problem of product processing time prediction under mixed-line and variable-batch production conditions. This paper preprocesses complex product processing time series and transforms the problem of product processing time prediction into a time series vector data prediction problem. This method is highly relevant for research on operation time prediction using machine learning.

This paper focuses on the project plan management control model, which previous investigators have rarely examined. For the first time, the time data predicted by machine learning were used as input to the project plan management control model, further improving the accuracy of the algorithm.

The actual product operation time data for enterprises and three different artificial intelligence model algorithms were compared. It was found that the attention mechanism model is more suitable for predicting production time and was verified as performing better in resolving gradient explosion and paying attention to global information compared to the MLP and LSTM methods.

We propose optimizing the CPM algorithm, which can dynamically track project progress and dynamically optimize the path. Using previous time prediction results the algorithm can further improve a manufacturing enterprise’s ability to control the total duration of complex projects. The improved CPM algorithm has shown a good control effect when two different sets of plan data are used (maintaining the critical path and changing the critical path). The robustness of the algorithm is verified through experiment.

With the development of information technology there is now a large amount of production process-related data available in manufacturing enterprises. Predicting production data through artificial intelligence is a novel approach, and in the future more product operation time data will need to be analyzed and validated. Artificial intelligence algorithms have strong potential for handling multiclassification and multiobjective optimization problems and can be further studied by combining modern management theory with a large amount of production data.

This study has several limitations, reflected in two main aspects. First, predicting homework time requires a certain number of historical samples. This requires an enterprise to achieve a certain level of production management informatization and accumulate product delivery time data. Second, the improved CPM algorithm and the “6n+5” model construction method are more suitable for solving the planning and management problems of aerospace or similarly complex structural products.

Our future focus will be on other applications of machine learning in the fields of planning and scheduling. The behavior of scheduling personnel in managing activities is simulated based on resource planning through machine learning. Using reinforcement learning methods, resource planning and tasks are treated as intelligent agents to achieve automatic scheduling of plans.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, T. L., Cheng, C. Y. & Chou, Y. H. Multi-objective genetic algorithm for energy-efficient hybrid flow shop scheduling with lot streaming. Ann. Op. Res. 290, 813–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-018-2969-x (2020).

Liu, G. S., Zhou, Y. & Yang, H. D. Minimizing energy consumption and tardiness penalty for fuzzy flow shop scheduling with state-dependent setup time. J. Clean. Prod. 147, 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.044 (2017).

Lu, P. H., Wu, M. C., Tan, H., Peng, Y. H. & Chen, C. F. A genetic algorithm embedded with a concise chromosome representation for distributed and flexible job-shop scheduling problems. J. Intell. Manuf. 29, 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-015-1083-z (2018).

Marichelvam, M. K., Geetha, M. & Tosun, Ö. An improved particle swarm optimization algorithm to solve hybrid flowshop scheduling problems with the effect of human factors–A case study. Comput. Op. Res. 114, 104812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2019.104812 (2020).

Zhao, F. et al. A factorial based particle swarm optimization with a population adaptation mechanism for the no-wait flow shop scheduling problem with the makespan objective. Expert Syst. Appl. 126, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.01.084 (2019).

Zarrouk, R., Bennour, I. E. & Jemai, A. A two-level particle swarm optimization algorithm for the flexible job shop scheduling problem. Swarm Intell. 13, 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11721-019-00167-w (2019).

Engin, O. & Güçlü, A. A new hybrid ant colony optimization algorithm for solving the no-wait flow shop scheduling problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 72, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2018.08.002 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, S., Luo, Y. & Zhang, L. Ant colony optimization for cuckoo search algorithm for permutation flow shop scheduling problem. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 7(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2018.1555063 (2019).

Elmi, A. & Topaloglu, S. Cyclic job shop robotic cell scheduling problem: Ant colony optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 111, 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2017.08.005 (2017).

Bożejko, W., Gnatowski, A., Pempera, J. & Wodecki, M. Parallel tabu search for the cyclic job shop scheduling problem. Comp. Ind. Eng. 113, 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2017.09.042 (2017).

Li, J. Q., Duan, P., Cao, J., Lin, X. P. & Han, Y. Y. A hybrid pareto-based tabu search for the distributed flexible job shop scheduling problem with E/T criteria. IEEE Access 6, 58883–58897. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2873401 (2018).

Shao, Z., Pi, D. & Shao, W. Estimation of distribution algorithm with path relinking for the blocking flow-shop scheduling problem. Eng. Optim. 50(5), 894–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305215X.2017.1353090 (2018).

Dabah, A., Bendjoudi, A., AitZai, A. & Taboudjemat, N. N. Efficient parallel tabu search for the blocking job shop scheduling problem. Soft Comput. 23, 13283–13295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-019-03871-1 (2019).

González-Neira, E. M. et al. Robust solutions in multi-objective stochastic permutation flow shop problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 137, 106026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2019.106026 (2019).

Arık, O. A. Population-based tabu search with evolutionary strategies for permutation flow shop scheduling problems under effects of position-dependent learning and linear deterioration. Soft Comput. 25(2), 1501–1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-020-05234-7 (2021).

Habibi, F., Barzinpour, F. & Sadjadi, S. J. A mathematical model for project scheduling and material ordering problem with sustainability considerations: A case study in Iran. Comput. Ind. Eng. 128, 690–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2019.01.007 (2019).

Wang, S., Wang, X., Chu, F. & Yu, J. An energy-efficient two-stage hybrid flow shop scheduling problem in a glass production. Int. J. Prod. Res. 58(8), 2283–2314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2019.1624857 (2020).

Vela, C. R., Afsar, S., Palacios, J. J., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, I. & Puente, J. Evolutionary tabu search for flexible due-date satisfaction in fuzzy job shop scheduling. Comput. Op. Res. 119, 104931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2020.104931 (2020).

Gmira, M., Gendreau, M., Lodi, A. & Potvin, J. Y. Tabu search for the time-dependent vehicle routing problem with time windows on a road network. Eur. J. Op. Res. 288(1), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2020.05.041 (2021).

Manna, A. K., Akhtar, M., Shaikh, A. A. & Bhunia, A. K. Optimization of a deteriorated two-warehouse inventory problem with all-unit discount and shortages via tournament differential evolution. Appl. Soft Comput. 107, 107388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107388 (2021).

Manna, A. K. & Bhunia, A. K. Investigation of green production inventory problem with selling price and green level sensitive interval-valued demand via different metaheuristic algorithms. Soft Comput. 26(19), 10409–10421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-022-06856-9 (2022).

Manna, A. K., Das, S., Shaikh, A. A., Bhunia, A. K. & Moon, I. Carbon emission controlled investment and warranty policy based production inventory model via meta-heuristic algorithms. Comput. Ind. Eng. 177, 109001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2023.109001 (2023).

Sha, Z., Xue, F. & Zhu, J. Scheduling strategy of cloud robots based on parallel reinforcement learning. J. Comput. Appl. 39(2), 501. https://doi.org/10.11772/j.issn.1001-9081.2018061406 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Learning to dispatch for job shop scheduling via deep reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1621–1632 (2020).

Swarup, S., Shakshuki, E. M. & Yasar, A. Task scheduling in cloud using deep reinforcement learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 184, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.03.016 (2021).

Luo, S. Dynamic scheduling for flexible job shop with new job insertions by deep reinforcement learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 91, 106208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106208 (2020).

Silva, M. A. L., de Souza, S. R., Souza, M. J. F. & Bazzan, A. L. C. A reinforcement learning-based multi-agent framework applied for solving routing and scheduling problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 131, 148–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.04.056 (2019).

Park, J., Chun, J., Kim, S. H., Kim, Y. & Park, J. Learning to schedule job-shop problems: Representation and policy learning using graph neural network and reinforcement learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59(11), 3360–3377. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1870013 (2021).

Fischer, T. & Krauss, C. Deep learning with long short-term memory networks for financial market predictions. Eur. J. Op. Res. 270(2), 654–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.11.054 (2018).

Su, Z., Xie, H. & Han, L. Multi-factor RFG-LSTM algorithm for stock sequence predicting. Comput. Econ. 57, 1041–1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-020-10008-2 (2021).

Mnih, V., Heess, N., & Graves, A. Recurrent models of visual attention. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 27, 1–9. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2014 (2014).

Kondo, T., Ueno, J. & Takao, S. Hybrid feedback GMDH-type neural network using principal component-regression analysis and its application to medical image recognition of heart regions. In 2014 Joint 7th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems (SCIS) and 15th International Symposium on Advanced Intelligent Systems (ISIS) 1203–1208 (IEEE, 2014).

Liu, J. et al. Learning abstract snippet detectors with temporal embedding in convolutional neural networks. In 2016 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE) 895–905 (IEEE, 2016).

Bao, W., Yue, J. & Rao, Y. A deep learning framework for financial time series using stacked autoencoders and long-short term memory. PLoS One 12(7), e0180944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180944 (2017).

Chakrabortty, R. K., Sarker, R. A. & Essam, D. L. Resource constrained project scheduling with uncertain activity durations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 112, 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2016.12.040 (2017).

Tripathi, K. K. & Jha, K. N. Determining success factors for a construction organization: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Manag. Eng. 34(1), 04017050. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000569 (2017).

Tripathi, K. K. & Jha, K. N. An empirical study on performance measurement factors for construction organizations. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 22, 1052–1066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-017-1892-z (2018).

Kadri, R. L. & Boctor, F. F. An efficient genetic algorithm to solve the resource-constrained project scheduling problem with transfer times: The single mode case. Eur. J. Op. Res. 265(2), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.07.027 (2018).

Olivieri, H., Seppänen, O. & Denis Granja, A. Improving workflow and resource usage in construction schedules through location-based management system (LBMS). Constr. Manag. Econ. 36(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2017.1410561 (2018).

Larsen, R. & Pranzo, M. A framework for dynamic rescheduling problems. Int. J.Prod. Res. 57(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1456700 (2019).

Fan, G. & Jiang, Z. Hybrid scheduling method for automatic guided vehicles in intelligent warehouses considering power management. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 130(7), 3685–3695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12900-1 (2024).

Yao, Y., Liu, L., Liu, X., Wang, M. & Sai, X. Internet of medical things for VTE patients in ICU: A self-attention mechanism-based energy-efficient risk identification scheduling algorithm. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 37(03), 2250192. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984922501925 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB1716200) and Research Funds for Leading Talents Program (048000514122549).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Liu, H., Xia, M. et al. A machine learning based EMA-DCPM algorithm for production scheduling. Sci Rep 14, 20810 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71355-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71355-w