Abstract

Partial remission (PR) occurs in only half of people with new-onset type 1 diabetes (T1D) and corresponds to a transient period characterized by low daily insulin needs, low glycemic fluctuations and increased endogenous insulin secretion. While identification of people with newly-onset T1D and significant residual beta-cell function may foster patient-specific interventions, reliable predictive biomarkers of PR occurrence currently lack. We analyzed the plasma of children with new-onset T1D to identify biomarkers present at diagnosis that predicted PR at 3 months post-diagnosis. We first performed an extensive shotgun proteomic analysis using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem-Mass-Spectrometry (LCMS/MS) on the plasma of 16 children with new-onset T1D and quantified 98 proteins significantly correlating with Insulin-Dose Adjusted glycated hemoglobin A1c score (IDAA1C). We next applied a series of both qualitative and statistical filters and selected protein candidates that were associated to pathophysiological mechanisms related to T1D. Finally, we translationally verified several of the candidates using single-shot targeted proteomic (PRM method) on raw plasma. Taken together, we identified plasma biomarkers present at diagnosis that may predict the occurrence of PR in a single mass-spectrometry run. We believe that the identification of new predictive biomarkers of PR and β-cell function is key to stratify people with new-onset T1D for β-cell preservation therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is the most prevalent chronic disease in children and is characterized by an immune-mediated attack against the β cells with various extents of pancreas inflammation1. In the weeks to years following the initiation of insulitis, people experience a progressive and asymptomatic demise of insulin-secreting cells2. Multiple individual cofactors (e.g., immunity, genetics, inflammation, metabolic stress, and β-cell sensitivity to stress) influence the degree and kinetics of β-cell decline2. When β-cell function falls by eighty percent, people experience a clinical state of insulinopenia with subsequent global metabolic disbalance (e.g., dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and eventually acidosis) and appearance of insulinopenia-related symptoms (i.e., polyuria, polydipsia, and weight loss), corresponding to clinical onset of the disease1,3.

Therapeutic advances of the past twenty years (e.g., glucose monitoring systems, insulin analogs and delivery systems) brought people with T1D supporting tools that enhanced day-to-day management and helped improve glycemic control1,4. To date, however, less than 30% of people with T1D achieve recommended glycemic targets5 leading to an incompressible prevalence of acute and chronic complications4,6,7 and consequent decrease in quality of life and reduction in lifespan expectancy8. Currently, disease-modifying therapies are missing as gaps remain in the understanding of T1D heterogeneity, holding persons to lifelong exogenous insulin substitution therapy9,10. Current efforts, such as the DIAbetes TAGging (DIATAG) consortium11, focus on a better characterization of T1D heterogeneity to achieve precision medicine9,10,11,12,13,14.

One specific example of T1D variable clinical evolution is the occurrence of partial remission (PR), in approximately 50% of new-onset patients, shortly after the initiation of insulin therapy. PR corresponds to a transient recovery of β-cell function that is clinically characterized by increased glycemic stability and low daily exogenous insulin requirements15. Mechanisms underlying PR remain controversial with recent studies suggesting a combination of improved insulin sensitivity, a relative recovery of immunotolerance against β cells, and a partial recovery of β-cell function16,17,18. Owing to the attempt at preserving residual β-cell function after T1D onset, favorable metabolic and immune conditions surrounding PR support the intervention-prone character of the period. Additionally, studies recently highlighted the positive duration-dependent residual effect of PR on short- (i.e., DIABHONEY study) and long-term glucose homeostasis19. While two recent studies described encouraging results20,21, the great majority of prevention therapies aiming to extend PR yielded short-lasting effects and patchy responses among people with new-onset T1D. This mostly results from the lack of reliable predictive (bio)markers to perform accurate stratification of participants at diagnosis9,22.

In-depth profiling of blood-derived specimens (i.e., plasma or serum) using mass-spectrometry approach allows the simultaneous detection and quantification of hundreds of circulating proteins23,24. While similar strategies were previously applied for biomarker discovery in autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, a recent review highlighted that only a very small amount of these studies included plasma samples from children with T1D25,26,27. Furthermore, proteomic studies in the T1D field mostly focused on the earliest stages of the disease (i.e., presymptomatic)25,27,28,29 or on distinguishing people with T1D from healthy controls23,29,30. Interestingly, an ancillary study from INNODIA consortium recently identified proteins that were associated with changes in biological fasting C-peptide/glucose values31. Focusing on clinical diversity (e.g., PR occurrence) rather than disease status (i.e., T1D vs healthy controls or pre- vs post-seroconversion) may provide new insights into the comprehension of T1D heterogeneity and the identification of new stratification biomarkers.

In the present study, we performed a deep proteomic characterization of plasma of children with new-onset T1D to identify biomarkers present at diagnosis and with a potential to predict the occurrence of PR 3 months postdiagnosis. Various data enrichment analyses were run on identified candidates to unravel pathways underlying PR.

Methods

Study population and design

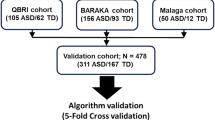

This is a subsidiary study of the multicentric DIATAG study that was previously described11. Briefly, participants aged between 6 months to 18 years old were recruited at clinical diagnosis of T1D that was defined by the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) criteria32. Participants were positive for at least one anti-islet autoantibody (i.e., anti-insulin, anti-insulinoma-associated antigen-2, anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, anti-Zinc transporter 8). Informed written consent was obtained for every parent and assent was obtained from participant when aged above 7 years old. The study protocol was approved by the seven participating ethical committees (Comité d’Ethique Hospitalo-Facultaire of Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc (2018/04DEC/462)) and is registered on www.clinicaltrial.gov (NCT04007809). Exclusion criteria are described elsewhere (NCT04007809).

Demographic data (i.e., age at diagnosis, sex, weight, height, and body mass index) and diabetes characteristics (i.e., presence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis, anti-islet antibodies, insulin regimen) were collected at diagnosis. Tanner stage was determined during the initial hospitalization for diabetes by a pediatric endocrinologist that classified the participants as prepubertal (Tanner I) or pubertal (Tanner II to V)33. When data obtained during the clinical examination were borderline (e.g., early M2 or testicular volume 4-6 mL) or absent, serum level of LH was measured on the baseline blood test where LH > 0.3 UI/L defined puberty onset. The baseline screening (i.e., blood draw, urine, and saliva) was performed after an overnight fast between 5 to 21 days after diagnosis, to allow metabolic stabilization (i.e., normalization of glucose levels, no acidosis or hypertriglyceridemia). From diagnosis, clinical parameters (i.e., insulin dose-adjusted A1C [IDAA1C], HbA1C, total insulin daily dose [TDD]) were collected at each outpatient clinical visit (i.e., every 3 months) for 1 year. All data were gathered inside the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system provided by Vanderbilt University (Nashville, USA) and hosted at Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc (CUSL).

Baseline plasma samples from sixteen participants with T1D from the DIATAG cohort were used for this study. These were carefully selected according to the participant’s remission status at + 3 months, pubertal status, sex, and participating center to reduce the influence of cofactors on plasma proteome analysis (i.e., age, sex, pre-analytical management of the samples).

Residual β-cell secretion (CPEPEST) was evaluated at + 3 months as described elsewhere11.

Determination of the remission status

Remission status was defined using the IDAA1C score, as follows: HbA1c (%) + (4 × insulin dose (IU/kg body weight per 24 h)34, with a score above 9 defining non-remitters and a score below 9 defining remitters. TDD was either reported by participants (i.e., multiple daily injection [MDI] users) or calculated using the software for pump users.

Blood samples collection

Venous whole blood was collected in EDTA tubes for plasma (Monovette®, Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). Within the 90 min of the sampling, collection tubes were centrifugated 15 min at 2000 g at 4 °C to achieve poor platelet plasma. The upper layer corresponding to plasma was slowly collected to avoid contamination by red blood cells (i.e., leaving the first 5 mm in the tube), and aliquoted and frozen at − 80 °C in the biobank until further use. The sample collection and preanalytical management of the samples were standardized in all participating centers.

Plasma samples preparation for proteomics

All samples were prepared simultaneously using the same batch of reagents. Plasma samples were thawed on ice before being centrifuged for 15 min at 14000 g to remove impurities. Plasma (1 mL) from each participant was depleted using ProteoMiner™ Protein Enrichment Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions35. We performed a volume-based normalizing method on the input as (1) human plasmatic proteins remain in a tight concentration range36 and (2) translation of the method to the clinic will be easier. Proteominer™ beads were washed three times before being eluted defining the eluate fraction. The eluate was collected and proteins were quantified using the Bradford method37. The depleted proteins (i.e., 250 µg) were further reduced and alkylated in low-bind Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf LoBind) as previously described38, before undergoing cold acetone precipitation overnight (i.e., − 20 °C, 4:1 volume). Proteins were washed twice using cold acetone, resuspended in 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate and digested overnight using trypsin (Promega; Madison, WI) at an enzyme:substrate ratio of 1:100 (37 °C under 750 rpm continuous agitation).

The resulting peptides were quantified using Pierce™ kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Peptides from each participant (100 µg per participant) were labelled with tandem mass tags (TMT, TMTproTM16plex, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples from all 16 participants were pooled in one final sample that was washed on a C18 column (HyperSep™ 200 mg, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove the excess TMT labeling and improve further analysis (i.e. reducing the background noise).

To further decrease the complexity of the proteome, we fractionated off-line by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the pooled labelled sample into 51 different fractions using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC)39,40. These were pooled two by two (i.e., 1 + 26, 2 + 27, […], 25 + 51) to reduce the number of samples while maintaining distinct hydrophilic characteristics, resulting in a total of 25 fractions (Fig. 1)41.

Schematic representation of the experimental workflow. Sixteen plasma samples of patients with new-onset T1D (i.e., between 5–21 days postdiagnosis) were depleted using ProteoMiner™ kit prior to an overnight digestion by trypsin. Resulting peptides were labelled using isobaric TMTpro 16plex™ before being pooled into a single sample and further separeted into 51 fractions using HILIC. Most orthogonal fractions of labelled-peptides were pooled together (i.e., 1 + 26, 2 + 27,[…], 25 + 51) resulting in a total of 25 DDA LC–MS/MS runs that were subsequently analyzed and quantified using Proteome Discoverer Software. Correlations between protein relative abundance and IDAA1C score was performed using linear mixed models. Various qualitative and statistical approaches were used to filter best candidates within significant proteins resulting in a total of 26 candidates. FDR false discovery rate, HILIC hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, IDAA1C insulin dose-adjusted A1C, ORA overrepresentation analysis, RF random forest, SVM support vector machine, T1D type 1 diabetes.

Relative quantification by liquid chromatography-tandem-mass-spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

One µg of peptides dissolved in solvent A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid [TFA] in 2% acetonitrile [ACN]) was directly loaded onto a reversed-phase pre-column (Acclaim PepMap 100, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and eluted in backflush mode. Peptide separation was achieved using a reversed-phase analytical column (Acclaim PepMap RSLC, 0.075 × 250 mm, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a 140 min linear gradient of 4%–32% solvent B (0.1% TFA in 80% ACN) for 99 min, 32%–60% solvent B for 10 min, 60%–95% for 1 min and holding at 95% for the last 10 min at a constant flow rate of 300 nL/min on an Ultimate 3000 RSLC nanoHPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Vienna, Austria). The peptides were analyzed by an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with enabled advanced peak determination (APD) and relative quantification was allowed by either MS2 or SPS MS3 scans. Intact peptides were detected in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 120.000 with a scan range m/z from 375 to 1500 and an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 4 × 105, maximum injection time was set to 50 ms. A data-dependent procedure of MS/MS scans was applied for the top precursor ions above a threshold ion count of 5 × 103 in the MS survey scan with 60 s dynamic exclusion. The total cycle time was set to 3 s. For MS2 identification of peptide sequence and quantification of the TMT reporter ions, MS2 spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 50.000 after higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation at 35% with an AGC target of 1 × 105 ions and a maximum injection time of 120 ms. For MS3 quantification, MS2 spectra for identification were first acquired in the Ion Trap after Collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation at 30%, for quantification 10 precursors from the MS2 scan were synchronously selected (SPS MS3) for HCD fragmentation at 55%, and the MS3 spectra was acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 50.000 with an AGC of 2 × 105 and a maximum injection time of 120 ms. MS/MS spectra were exported using the following settings: peptide mass range: 350–5000 Da, minimal total ion intensity: 500.

Protein detection and quantification

For protein identification, MS/MS data were processed using Sequest HT search engine within Proteome Discoverer 2.5 against a human protein reference target-decoy database obtained from Uniprot. Trypsin was specified as the cleavage enzyme, allowing up to 2 missed cleavages, 4 modifications per peptide, and up to 3 charges. Relative quantification of proteins was performed according to the signal of the TMT reporter’s ions in MS2 or MS3 spectra. The false discovery rate (FDR) was set at less than 1%. Statistical analysis was performed according to remission status.

Statistical analysis according to remission status and IDAA1C score

All statistical analyses were performed with R (R Core Team [2021]. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL [https://www.R-project.org/], v4.0.3) including principal component analysis (PCA), volcano plots, linear mixed models and enrichment analysis. Preprocessed data (see above) were log-transformed, centered, and scaled to achieve a normal distribution. Influences of various cofactors (i.e., sex, puberty status, center, manipulation operator) were manually visualized on PCA plots (Supplemental Fig. 1). Protein abundance differences according to remission status at + 3 months were analyzed both as a categorical (i.e., remitters vs non-remitters) or a continuous variable (i.e., IDAA1C score) using linear mixed models using statistical R package Limma (v3.46.0)42. Missing values were imputed before PCA and omitted for linear mixed models. Models included the remission status or IDAA1C score as fixed effects, and participant sex and pubertal status as a random intercept. Residuals were visualized on Q-Q plots. Correlations between PRM and TMT methods were assessed using Spearman’s correlation (package stats, v3.6.2). The level of significance was considered as p value below 0.05 for every analysis.

Data quality check and data mining for the identification of predictive biomarkers

Potential blood cell-derived contaminations were investigated as previously described43 by comparing their contaminant lists (e.g., platelet, erythrocytes or coagulation cascade) to our dataset. Distributions of the latter across our samples were visualized to identify potential outliers.

Enrichment analyses were performed independently using over-representation analysis (ORA) based on Molecular Signatures Database (msigdbr package, v7.5.1), and Pathway studio network analysis (https://www.elsevier.com/products/embiology, Elsevier [accessed: January 2020]) on significantly differentially expressed proteins. Pathway studio is a database that allows both non-targeted and targeted investigations on interactions between genes, diseases, drugs, and cells based on a collection of more than 25 million Pubmed abstracts, 1700 full-text journals, and results from 200.000 clinical trials.

Unbiased approach to identify the best combination of biomarkers using random forest and spectral vector machine approaches

To identify the best combination of biomarkers to predict the remission status at + 3 months, predictive modelling was combined to a wrapper feature selection technique called Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). The underlying predictive models are Random Forest and radial Support Vector Machine (SVM) in a classification context. The models and the feature selection procedure were implemented with the caret R package (v6.0)44.

Verification of biomarker candidates in raw plasma using targeted LC–MS/MS

The raw plasma samples from each participant (n = 15) were diluted using a dilution factor of 1:60 to reach an approximative final concentration between 1 and 2 mg/dL. Plasma was centrifugated for 15 min at 20000 g to remove debris before being reduced, alkylated, precipitated and digested as described here above. Peptides were identified and quantified by a targeted Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM)45 method based on proteotypic peptides (identified in SRM Atlas and Peptide Atlas databases) and their calculated m/z ratio. Between 1 and 4 peptides were targeted per protein of interest. Single run without pre-fractionation was performed for each sample. Peptides were analyzed on the same LC–MS/MS setup as described above with specific settings for PRM acquisition. The Orbitrap analyzer was operated in PRM mode using a resolution of 50.000 for MS1 and 30.000 for targeted MS2 scans, an AGC target of 4 × 105 Ions in MS1 and of 2.5 × 105 in MS2 with maximum injection time set to Auto. Peptides were selected for MS2 fragmentation with HCD collision energy set at 30%. Spectra were validated and peptide transitions were quantified using Skyline 32.2.0425 (MacCoss Lab, University of Washington).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The present study was performed on poor-platelet plasma samples from sixteen children of the DIATAG consortium. These samples were collected in five recruiting centers with similar sample preanalytical protocols after overnight fast 5 to 21 days after diagnosis of T1D (see Material and Methods subsection). Children were prepubertal (62%) with a mean ± SD age of 9.1 ± 4.2 years at diagnosis. Within this cohort, eight were remitters (i.e., IDAA1C score < 9 at 3 months postdiagnosis) and eight were non-remitters (i.e., IDAA1C score > 9 at 3 months postdiagnosis). Detailed characteristics of the cohort are provided in Table 1. Schematic representation of the experimental workflow is presented in Fig. 1.

Comprehensive analysis of plasma proteome in children with new-onset T1D

To provide an overview of the plasma proteome in children with new-onset T1D, we performed a comprehensive identification and relative quantification of depleted plasma from fractionated total peptides. A total of 1627 unique proteins were identified with an FDR < 0.01 using Proteome Discoverer ™ software framework. Among them, the great majority were detected and quantified across all plasma samples (n = 1493).

Interestingly, crossing our data with HUPO dataset47, we showed that depletion and fractionation enabled the expansion of the detection range of the mass-spectrometer from ± 104 to a magnitude of 107 with more than 150 very low plasmatic concentration proteins quantified (i.e., below 10 ng/dL). Furthermore, comparing our data to previous large-scale plasmatic proteomic datasets48,49, we showed a high overlap between our data and studies from both Liu et al. and Keshishian et al. Notably, 660 proteins were solely identified in our experiment.

Plasma proteome at diagnosis may improve the prediction of non-remission in people with newly-onset T1D

To investigate whether plasmatic protein levels measured at diagnosis predicted the occurrence of PR at 3 months, data from our untargeted proteomic analysis were analyzed according to PR status either considered as a dichotomic event (i.e., remitter or non-remitter) or a continuous scale (i.e., IDAA1C score). As age and sex influenced plasma proteome in healthy children49, linear mixed models fitted for sex and pubertal status were used for differential analyses.

When considering PR as a dichotomic event, we found no differentially expressed plasmatic proteins at T1D diagnosis between participants that will undergo PR or not at 3 months (all adjusted p-values > 0.05). However, as PR demonstrated to be a continuous phenomenon11, we correlated relative plasmatic concentrations to the IDAA1C score and identified 98 significant candidates (adjusted p-values < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Most significant proteins distributed asymmetrically with the great majority showing a positive correlation with IDAA1C score. P-value and protein fold-change (i.e., per unit of IDAA1C) of significantly correlated proteins are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Graphical representation of erythrocyte, coagulation, and platelet plasmatic contamination. Volcano plots of plasma proteins' relative abundance according to IDAA1C score. Red points represent erythrocyte (A), coagulation (B), and platelet (C) contaminants. Dashed horizontal black lines represent the significance level threshold (p adjusted < 0.05). Distribution of platelet contaminants abundances across plasma samples (D). Samples are ranked according to their IDAA1C value at 3 months postdiagnosis (i.e., smallest IDAA1C is n°1). The level of significance is represented as 0 (adjusted p value > 0.05) or 1 (adjusted p value < 0.05). The color of the points represents IDAA1C score.

Candidate plasma proteins are not contaminants from the blood cell compartment

As preanalytical treatment of samples may induce bias, dataset was screened for the presence of contaminants as described by Geyer et al.43. Lists of potential contaminant proteins for erythrocytes lysis, coagulation events, and platelets contamination were retrieved to evaluate the overlap with candidate proteins43.

While most of proteins listed as platelet, coagulation and erythrolysis contaminant were detected in our dataset, these were mostly found in low abundance. Interestingly, none of our proteins of interest were recognized as erythrocyte or coagulation contaminants (Fig. 2A,B). Focusing on platelet contamination, 11 of 98 candidates were recognized as potential plasmatic contaminants (i.e., TUBB1, TUBB4B, PARVB, TPM4, CAVIN2, VCL, FERMT3, TLN1, PLEK, TAGLN2, YWHAZ) though rest of platelet contaminants distributed heterogeneously within the volcano plot (i.e., both overexpressed and underexpressed) (Fig. 2C).

Deepening the characterization of platelet contamination, we looked at the global distribution of these contaminant proteins in the samples to identify potential outliers and investigate the presence of a global trend in their abundance across IDAA1C values. As shown in Fig. 2D, platelet contaminants were homogeneously distributed across all samples (i.e., similar relative abundance) without demonstrating an IDAA1C-specific pattern.

Qualitative and statistical approaches to identify the most reliable candidates

To identify the most promising biomarkers for validation studies, we performed an exhaustive literature search of all potential candidates (i.e., qualitative approach). These were further classified into six pivotal clusters related to diabetes (i.e., insulin secretion, cellular stress, inflammation markers, lipid metabolism, muscle, and diabetes-related complications (i.e., micro- and macrovascular)). Relationships between our protein candidates and pathways, gene regulation networks or protein interactions related to diabetes were investigated using Pathway Studio software (http://www.pathwaystudio.com)50. From our list of candidates, about half was associated with key mechanisms implicated in T1D physiopathology (e.g., insulin secretion and resistance, inflammation, endothelial reticulum stress and protein folding, regulation of INS gene).

In a complementary way, we performed an unbiased approach using both random forest (with [RFE_RF] or without [RF] recursive feature elimination) and support vector machine (SVM) (i.e., statistical approach). To avoid over-adjustment of the models, post statistical analyses were solely conducted on differentially expressed proteins (p < 0.05, n = 98). Interestingly, 36 proteins were selected by at least one post-analysis clustering method with some of them being selected by two (n = 6) or three (n = 6) methods (data not shown). Cross-validation was performed for each method with R2RF = 0.51, R2RFE-RF = 0.53, R2RF-SVM = 0.43.

Combined filters from both qualitative and statistical approaches were used to funnel potential candidates to a total of 26 plasmatic proteins. Characteristics of the latter (i.e., fold change [FC] and p value) are represented according to their diabetes-related cluster in Fig. 3.

Summary of the 26 protein candidates' characteristics. Protein candidates were classified according to their diabetes-related cluster (i.e., insulin secretion, cellular stress, inflammation, lipotoxicity, vascular complications, or marker of muscle atrophy). Some proteins may be found in more than one cluster. For each protein, adjusted p value, fold change and identification as potential platelet contaminant is indicated. Fold change is expressed in log2 and corresponds to the degree of protein expression change per unit of IDAA1C.

Mass spectrometric parallel reaction monitoring verified several protein candidates in raw plasma

To confirm our candidates and ease the translation to clinical settings, we performed targeted PRM proteomic on fourteen of the previous raw plasma samples (i.e., without pretreatment with PM). Proteotrypic peptides (i.e., that are unique to the protein of interest upon trypsin cleavage) and potential quantotypic peptides (i.e., that accurately represent the level of the protein) were identified using SRMAtlas and PeptideAtlas and differed from the ones quantified in the TMT experiment51 (Supplemental Table 2). Correlation plots between both quantitative methods (i.e., PRM and TMT) were investigated.

Using a single MS run for each sample, we identified and quantified 16 potential candidates with at least one quantotypic peptide. From these proteins, 13 peptides (11 proteins) significantly correlated with the IDAA1C score (R = 0.55–0.86, p < 0.05) with peptides from tubulins (i.e., TUBA4A, TUBB1, TUBB4B), YWHAZ and UNC13D showing the strongest correlations (i.e., R > 0.70) (Fig. 4). Also, significant correlations were found between residual CPEPEST at 3 months post-diagnosis and TAOK1, SKAP2, WDR44 and UNC13D (Supplemental Fig. 2). As IDAA1C values demonstrated a huge gap (i.e., no samples) in the 11–14 range, we performed a subanalysis excluding the participant with the highest IDAA1C (i.e., score of 14). Similar trends were maintained for most of protein candidates with peptides from tubulins (TUBA4A, TUBB1, TUBB4B), YWHAZ and UNC13D significantly correlating with the IDAA1C score (R > 0.6, p < 0.05).

Relations between peptides’ plasmatic abundances at clinical onset of type 1 diabetes and IDAA1C score at 3 months postdiagnosis (n = 14). AUC were integrated from the MS2 data for each peptide. Each panel represents linear regression with 95% CI bands (shaded zone) between peptide transitions area under the curve and IDAA1C score. Each point corresponds to one participant. Color of the point corresponds to one protein. Correlations were calculated using Spearman method (R). AUC area under the curve, IDAA1C insulin dose-adjusted A1C. Correspondence between quantotypic peptide and protein can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Importantly, PRM results significantly with TMT results for seven proteins with trends observed for an additional five proteins (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

Identification of early predictive biomarkers of PR occurrence in people with new-onset T1D may foster patient-specific interventions (e.g., initiation of immunomodulatory therapies, achieving tight glycemic control) and prevent further β-cell loss. In this context, quantification of proteins in easily collectible samples may provide potential new biomarkers (e.g., plasma proteome). To the best of our knowledge, we performed one of the most extensive shotgun proteomic analysis to characterize the plasmatic proteome at T1D onset and the first to identify predictive markers of PR. A combination of both qualitative (i.e., ORA and Pathway studio) and statistical (i.e., RF and SVM) filters funneled protein candidates which were subsequently classified into six diabetes-related clusters. Finally, several of those candidates were orthogonally verified on raw plasma (i.e., without pre-processing) using targeted proteomic (i.e., PRM method).

Most studies using plasma or serum proteomic to identify new disease biomarkers use a bottom-up strategy (i.e., triangle approach52) concomitantly with sample decomplexification methods. Similarly, we performed shotgun proteomic on depleted and fractionated plasma allowing a deeper proteome profiling than most studies on body fluids (i.e., plasma or serum) in the field of T1D27,28,29,53,54,55,56,57. Interestingly, our approach also allowed the quantification of low-abundance proteins which demonstrated to be a major reservoir for potential biomarkers48,52. Nonetheless, caution must be taken when interpreting results from depleted matrix as depletion modifies the composition of the initial proteome. Subsequent verification of biomarker candidates in non-depleted samples and using a complementary method is thus mandatory (e.g., PRM, ELISA, western blot)52.

Another source of confounding factors leading to the paucity of reproducibility in proteomic studies stands in the poor standardization of the type of matrix used (i.e., serum vs plasma) and the sample pretreatment steps (i.e., timing before sample pretreatment, centrifugation parameters)58,59. These elements may lead to heterogeneity in contaminations related to blood cells components (e.g., platelet quantity, hemolysis, coagulation) and alteration of the initial proteome. As suggested by the HUPO project, we used poor-platelet plasma as our matrix (i.e., less influence of coagulation and platelets)47 and performed a quality-check of the samples using recently described method43. Unsurprisingly, some of our candidates were classified as quality markers of platelet contamination though a majority of proteins identified in the platelet list did not correlate with IDAA1C score. Moreover, some contaminants that were significantly correlated to IDAA1C score demonstrated a role in the diabetes field (e.g., YWHAZ) (Fig. 3). Summarizing the influence of these factors on the identification of biomarkers, a recent study highlighted that more than 54% of plasma proteomic studies reported at least one significantly altered protein that was identified as a potential contaminant (i.e., quality marker)43.

Interestingly, we identified Src-kinase associated protein 2 (SKAP2) and Crk-like protein (CRKL) as potential candidates using both TMT labeling and PRM methods (R > 0.67, p < 0.05). Both proteins are involved in innate and adaptative immunity respectively, which are dysregulated in people with T1D60,61,62. On the one hand, SKAP2 influenced both β-cell sensitivity to cytokines (i.e., increased sensitivity when downregulated) and macrophage activity (i.e., increased activity when upregulated)63,64. Furthermore, specific polymorphism of SKAP2 gene (i.e., overexpression in immune cells) was associated with an increased pejoration of glucose homeostasis during the first year of T1D61. Our results may indicate an increase in macrophage activity in non-remitters. On the other hand, CRKL was associated with the selective migration of effector T cells towards inflammatory organs leading to graft-versus-host disease in mice65 that was reduced after gene knock-out. In humans, overexpression of CRKL was implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus66.

T1D is also characterized by a progressive reduction in β-cell mass and insulin secretion. In our dataset, protein 14-3-3 ζ/δ (YWHAZ) correlated with IDAA1C score at + 3 months suggesting that increased circulating levels of YWHAZ predicted higher dysglycemia. YWHAZ is a ubiquitous protein that plays a major role in glucose homeostasis. First, overexpression of YWHAZ inhibited incretin secretion with whole-body 14-3-3-KO mice showing an increase in GLP-1 and consequently insulin circulating levels67. Secondly, a recent study highlighted the β-cell specific role of 14-3-3ζ isoform on the first phase of insulin secretion68. Indeed, the authors found that 14-3-3ζ expression restrained insulin release by inhibiting mitochondrial function68. Furthermore, they also showed that specific inhibition of 14-3-3ζ in cultured human islets from people with T2D enhanced insulin secretion, mitochondrial function, and proliferation. While most of these mechanisms were described in models and people with T2D, utilization of drugs either increasing GLP-1 or inhibiting 14-3-3 proteins led to an improvement of insulin secretion in models of T1D (i.e., NOD mice)69 or people with new-onset T1D70.

Insulin deficiency, which is the main feature of T1D, leads to global metabolic disorders affecting the whole organism (e.g., gluco- and lipotoxicity, acidosis, insulinoresistance, proinflammatory conditions). Tubulins are proteins implicated in the formation of cell microtubules. While implications of those proteins have been mainly described in platelet dysfunctions, cancers and inflammation, there is a lack of evidence on the role of these proteins in T1D. Our results may not be directly derived from β cells but rather indicate a global release of those proteins in the context of global metabolic stress and inflammation.

Finally, targeting a clinically reliable witness of glucose homeostasis, we chose to predict the IDAA1C score rather than correlating with residual C-peptide secretion31. Recent data arising from our group and others supported strong correlations between IDAA1C and direct measures of glucose homeostasis (e.g., clinical parameters or continuous glucose monitoring data) while poorly correlating with residual β-cell secretion markers11,71,72,73. Furthermore, our results also supported that PR period was characterized by a continuum of glucose dysregulations rather than a dichotomic event. Indeed, significant proteins were only identified by linear regression predicting IDAA1C values at 3 months. This hypothesis was previously supported by our team11 which showed an overlap of glucose homeostasis metrics in remitters and non-remitters with intermediate IDAA1C values (i.e., in the 8–10 range).

Our study demonstrates several strengths. This is the first study that performed a deep characterization of plasma proteome at diagnosis of T1D to identify predictive markers of PR period in a pediatric cohort. Furthermore, we performed a quality check of plasma sample data to identify potential bias linked to blood cell contamination. Finally, protein candidates were verified using a complementary method (i.e., targeted proteomic) that allowed the verification of several candidates in raw plasma using a single MS-run with high sensitivity and specificity, improving the translation of the method to the clinic.

Our study was also limited by different factors. Utilization of low-abundance enrichment (i.e., Proteominer™) over high-affinity depletion (e.g., Top14™) methods may lead to a loss of proteins in the unbound fraction. Nonetheless, this loss may be limited as recent study showed on the one hand high overlap between bound and unbound PM fractions (91%) and on the second hand between ProteoMiner™ and other depletion methods74. Contaminant proteins belonging to platelets, erythrocytes and coagulation cascade were detected in all samples leading to potential bias. Nonetheless, the impact of the latter was limited as their distribution demonstrated to be homogeneous across all samples (i.e., analysis and identical SOP across recruiting centers). Also, the participant with an IDAA1C value of 14 acted as an outlier in our analysis. Potential confounders such as weight loss and metabolic disturbance at diagnosis may influence the proteome though waiting for metabolic stabilization before screening blood test may homogenize most of these confounders across the samples. Finally, the small number of participants may also limit the results and must be supported by extending investigations in the whole cohort.

Conclusion

Our study deepened the characterization of plasma proteome of children with new-onset T1D. Interestingly, abundance of nearly a hundred unique proteins at disease onset significantly predicted IDAA1C score at 3 months postdiagnosis but not the remission status, supporting PR as a continuum rather than a binary phenomenon. Quantitative (e.g., statistical) and quality (e.g., contaminants or pathways) funneled candidate list to proteins that were linked to pivotal clusters related to diabetes (i.e., insulin secretion, cellular stress, inflammation markers, lipid metabolism, muscle, and diabetes-related complications (i.e., micro- and macrovascular)). In a translational perspective, 12 of these predictive candidates were verified in the raw plasma using single-run targeted proteomic. We believe that the identification of new predictive biomarkers of PR and β-cell function is key to stratify people with new-onset T1D for β-cell preservation therapies.

Data availability

All raw files were uploaded in PRIDE (Proteome Exchange) with the data set identifier PXD049795 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD049795).

References

DiMeglio, L. A., Evans-Molina, C. & Oram, R. A. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 391, 2449–2462 (2018).

Atkinson, M. A., Roep, B. O., Posgai, A., Wheeler, D. C. S. & Peakman, M. The challenge of modulating β-cell autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7, 52–64 (2019).

Roep, B. O., Thomaidou, S., van Tienhoven, R. & Zaldumbide, A. Type 1 diabetes mellitus as a disease of the β-cell (do not blame the immune system?). Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 150–161 (2021).

Nathan, D. M. Realising the long-term promise of insulin therapy: The DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetologia 64, 1049–1058 (2021).

Saiyed, M. et al. Worldwide differences in childhood type 1 diabetes: The SWEET experience. Pediatr. Diabetes 22, 207–214 (2021).

Chatwin, H. et al. The impact of hypoglycaemia on quality of life outcomes among adults with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 174, 108752 (2021).

Mathieu, C. Minimising hypoglycaemia in the real world: The challenge of insulin. Diabetologia 64, 978–984 (2021).

Livingstone, S. J. et al. Estimated life expectancy in a scottish cohort with type 1 diabetes, 2008–2010. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 313, 37–44 (2015).

Deligne, C., You, S. & Mallone, R. Personalized immunotherapies for type 1 diabetes: Who, what, when, and how?. J. Pers. Med. 12, 542 (2022).

Linsley, P. S., Greenbaum, C. J. & Nepom, G. T. Uncovering pathways to personalized therapies in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 70, 831–841 (2021).

Pollé, O. G. et al. Glycemic variability patterns strongly correlate with partial remission status in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 45, 2360–2368 (2022).

Battaglia, M. et al. Introducing the endotype concept to address the challenge of disease heterogeneity in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 43, 5–12 (2020).

Long, S. A. et al. Partial exhaustion of CD8 T cells and clinical response to teplizumab in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Sci. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aai7793 (2016).

Battaglia, M. et al. Identifying the ‘Achilles heel’ of type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 204, 167–178 (2021).

Fonolleda, M., Murillo, M., Vázquez, F., Bel, J. & Vives-Pi, M. Remission phase in paediatric type 1 diabetes: New understanding and emerging biomarkers. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 88, 307–315 (2017).

Tang, R., Zhong, T., Wu, C., Zhou, Z. & Li, X. The remission phase in type 1 diabetes: Role of hyperglycemia rectification in immune modulation. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00824 (2019).

Zhong, T. et al. The remission phase in type 1 diabetes: Changing epidemiology, definitions, and emerging immuno-metabolic mechanisms. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 36, 2 (2020).

Bensellam, M., Jonas, J.-C. & Laybutt, D. R. Mechanisms of β-cell dedifferentiation in diabetes: Recent findings and future research directions. J. Endocrinol. 236, R109–R143 (2018).

Niedzwiecki, P. et al. Influence of remission and its duration on development of early microvascular complications in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complic. 29, 1105–1111 (2015).

Waibel, M. et al. Baricitinib and β-cell function in patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 2140–2150 (2023).

Herold, K. C. et al. Teplizumab: A disease-modifying therapy for type 1 diabetes that preserves β-cell function. Diabetes Care 46, 1848–1856 (2023).

Besser, R. E. J. et al. <scp>ISPAD</scp> clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: Stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 23, 1175–1187 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Serum proteomics reveals systemic dysregulation of innate immunity in type 1 diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 210, 191–203 (2013).

Nakayasu, E. S. et al. The role of proteomics in assessing beta-cell dysfunction and death in type 1 diabetes. Expert Rev. Proteomics 16, 569–582 (2019).

Liu, C. W. et al. Temporal expression profiling of plasma proteins reveals oxidative stress in early stages of Type 1 Diabetes progression. J. Proteomics 172, 100–110 (2018).

McCafferty, C., Chaaban, J. & Ignjatovic, V. Plasma proteomics and the paediatric patient. Expert Rev. Proteomics 16, 401–411 (2019).

Webb-Robertson, B.-J.M. et al. Decrease in multiple complement proteins associated with development of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes. iScience 27, 108769 (2023).

Nakayasu, E. S. et al. Plasma protein biomarkers predict the development of persistent autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes 6 months prior to the onset of autoimmunity. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 101093 (2023).

Sarkar, S. et al. Systematic review of type 1 diabetes biomarkers reveals regulation in circulating proteins related to complement, lipid metabolism, and immune response. Clin. Proteomics 20, 1–16 (2023).

Bissenova, S. et al. NET proteome in established type 1 diabetes is enriched in metabolic proteins. Cells 12, 1319 (2023).

Moulder, R. et al. Targeted serum proteomics of longitudinal samples from newly diagnosed youth with type 1 diabetes distinguishes markers of disease and C-peptide trajectory. Diabetologia 66, 1983–1996 (2023).

Mayer-Davis, E. J. et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 19, 7–19 (2018).

Roberts, C. Tanner’s Puberty Scale: Exploring the historical entanglements of children, scientific photography and sex. Sexualities 19, 328–346 (2016).

Mortensen, H. B. et al. New definition for the partial remission period in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32, 1384–1390 (2009).

Lee, P. Y., Osman, J., Low, T. Y. & Jamal, R. Plasma/serum proteomics: Depletion strategies for reducing high-abundance proteins for biomarker discovery. Bioanalysis 11, 1799–1812 (2019).

Paul, J. & Veenstra, T. D. Separation of serum and plasma proteins for in-depth proteomic analysis. Separations 9, 89 (2022).

Bradford, M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Ouni, E. et al. Divide-and-conquer matrisome protein (DC-MaP) strategy: An MS-friendly approach to proteomic matrisome characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9141 (2020).

Batth, T. S., Francavilla, C. & Olsen, J. V. Off-line high-pH reversed-phase fractionation for in-depth phosphoproteomics. J. Proteome Res. 13, 6176–6186 (2014).

Narváez-Rivas, M., Vu, N., Chen, G.-Y. & Zhang, Q. Off-line mixed-mode liquid chromatography coupled with reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry to improve coverage in lipidomics analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 954, 140–150 (2017).

Ward, B. et al. Deep plasma proteomics with data-independent acquisition: A fastlane towards biomarkers identification. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.23.581160 (2024).

Smyth, G. K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3, 1–25 (2004).

Geyer, P. E. et al. Plasma proteome profiling to detect and avoid sample-related biases in biomarker studies. EMBO Mol. Med. 11, e10427 (2019).

Kuhn, M. Package ‘caret’ Title Classification and Regression Training. (2022).

Bourmaud, A., Gallien, S. & Domon, B. Parallel reaction monitoring using quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer: Principle and applications. Proteomics 16, 2146–2159 (2016).

Wentworth, J. M. et al. Beta cell function in type 1 diabetes determined from clinical and fasting biochemical variables. Diabetologia 62, 33–40 (2019).

Omenn, G. S. THE HUPO human plasma proteome project. PROTEOMICS Clin. Appl. 1, 769–779 (2007).

Keshishian, H. et al. Multiplexed, quantitative workflow for sensitive biomarker discovery in plasma yields novel candidates for early myocardial injury. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 2375–2393 (2015).

Liu, C.-W. et al. Temporal profiles of plasma proteome during childhood development. J. Proteomics 152, 321–328 (2017).

Yuryev, A., Kotelnikova, E. & Daraselia, N. Ariadne’s ChemEffect and pathway studio knowledge base. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 4, 1307–1318 (2009).

Holman, S. W., Sims, P. F. G. & Eyers, C. E. The use of selected reaction monitoring in quantitative proteomics. Bioanalysis 4, 1763–1786 (2012).

Geyer, P. E., Holdt, L. M., Teupser, D. & Mann, M. Revisiting biomarker discovery by plasma proteomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 13, 942 (2017).

von Toerne, C. et al. Peptide serum markers in islet autoantibody-positive children. Diabetologia 60, 287–295 (2017).

Albrethsen, J. et al. Evaluation of a type 1 diabetes serum cohort by SELDI-TOF MS protein profiling. PROTEOMICS Clin. Appl. 3, 383–393 (2009).

Zhi, W., Purohit, S., Carey, C., Wang, M. & She, J.-X. Proteomic technologies for the discovery of type 1 diabetes biomarkers. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 4, 993–1002 (2010).

Zhi, W. et al. Discovery and validation of serum protein changes in type 1 diabetes patients using high throughput two dimensional liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and immunoassays. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M111.012203 (2011).

Moulder, R. et al. Serum proteomes distinguish children developing type 1 diabetes in a cohort with HLA-conferred susceptibility. Diabetes 64, 2265–2278 (2015).

Halvey, P. et al. Variable blood processing procedures contribute to plasma proteomic variability. Clin. Proteomics 18, 1–14 (2021).

Nambu, M. et al. Effects of differences in pre-analytical processing on blood protein profiles determined with SWATH-MS. J. Proteomics 223, 103824 (2020).

Rutsch, N. et al. Diabetes with multiple autoimmune and inflammatory conditions linked to an activating SKAP2 mutation. Diabetes Care 44, 1816–1825 (2021).

Fløyel, T. et al. SKAP2, a candidate gene for type 1 diabetes, regulates β-cell apoptosis and glycemic control in newly diagnosed patients. Diabetes 70, 464–476 (2021).

Wilmink, M. & Spalinger, M. R. SKAP2—A molecule at the crossroads for integrin signalling and immune cell migration and function. Biomedicines 11, 2788 (2023).

Sano, H. & Imagawa, A. Research following genome-wide association study focuses on the multifaceted nature of Src kinase-associated phosphoprotein 2 in type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 13, 611–613 (2022).

Brorsson, C. A. et al. Genetic risk score modelling for disease progression in new-onset type 1 diabetes patients: Increased genetic load of islet-expressed and cytokine-regulated candidate genes predicts poorer glycemic control. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 1–8 (2016).

Huang, Y. et al. CRK proteins selectively regulate T cell migration into inflamed tissues. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 1019–1032 (2015).

Shi, X. et al. Downregulated miR-29a promotes B cell overactivation by upregulating Crk-like protein in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mol. Med. Rep. 22, 841–849 (2020).

Lim, G. E. et al. Ywhaz/14-3-3ζ deletion improves glucose tolerance through a GLP-1-dependent mechanism. Endocrinology 157, 2649–2659 (2016).

Mugabo, Y. et al. 14–3–3ζ Constrains insulin secretion by regulating mitochondrial function in pancreatic β cells. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.156378 (2022).

Maki, T., Gottschalk, R., Ogawa, N. & Monaco, A. P. Prevention and cure of autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice by continuous administration of FTY720. Transplantation 79, 1051–1055 (2005).

Ceriello, A. et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 reduces endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress induced by both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 36, 2346–2350 (2013).

Boyle, K. D. et al. Two- and Four-Hour tests differ in capture of C-peptide responses to a mixed meal in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 39, e76–e78 (2016).

Ruan, Y. et al. Mixed-meal tolerance test to assess residual beta-cell secretion: Beyond the area-under-curve of plasma C-peptide concentration. Pediatr. Diabetes 20, 282–285 (2019).

Carr, A. L. J. et al. Measurement of peak C-peptide at diagnosis informs glycemic control but not hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes. J. Endocr. Soc. 5, 1–10 (2021).

Kaur, G. et al. Extending the depth of human plasma proteome coverage using simple fractionation techniques. J. Proteome Res. 20, 1261–1279 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participants for their collaboration in the study.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Fond National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS Spécialiste post-doctorant, FRIA grant, FSR starting grant), Belgian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology (BESPEED), Société Francophone du Diabète (SFD), Fonds de la Recherche Clinique. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of these organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.P. contributed to the design and coordination of the study, collected samples, performed manipulation, wrote the first draft and revised the manuscript. S.P.D.R contributed to the design of the study, performed manipulation, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript. M.M., L.G. and D.V. participated in the design and analysis of the data, reviewed the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript. C.H., J.L. and G.H. performed manipulations, participated in the analysis of the data, and reviewed the first draft of the manuscript. P.L. contributed to the design and coordination of the study, interpreted data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript. P.L. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pollé, O.G., Pyr dit Ruys, S., Lemmer, J. et al. Plasma proteomics in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes identifies new potential biomarkers of partial remission. Sci Rep 14, 20798 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71717-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71717-4