Abstract

Central vision loss (CVL) is a major form of low vision that remains inadequately managed worldwide. This study evaluated the clinical efficacy of a novel head-mounted device (HMD), Onyx, designed to enhance visual function and vision-related quality of life for CVL patients. It employs a projection system that enables patients to leverage their residual peripheral vision for environmental awareness. It also integrates artificial intelligence to augment the automatic recognition of text, faces, and objects. In this single-center, prospective cohort study, 41 binocularly low vision patients with CVL were instructed to use Onyx for 4 to 6 h daily over a one-month period. Various metrics were assessed, including near and distance visual acuity (VA), recognition abilities for faces and objects, and the low vision quality-of-life (LVQOL) questionnaire scores, at the start and end of the study. The results showed significant improvements in near VA for 60.98% of the participants, distance VA for 80.49%, and recognition ability for 90.24%. 68.29% of the participants showed significant improvements in the LVQOL scores. Improvement in recognition ability was negatively correlated with baseline recognition ability. Additionally, improvement in the LVQOL scores was correlated with age and the baseline LVQOL score. Overall, the study found that the novel HMD significantly improved visual function and vision-related quality of life for low vision patients with CVL, highlighting the potential benefits and the need for further evaluation of such devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the aging of society, age-related retinal diseases are increasingly causing vision impairment. Central vision loss (CVL), which affects the central retinal area responsible for the high visual acuity, is a major form of this impairment1. Nearly 75% of patients seeking low vision rehabilitation services suffer from CVL, significantly affecting crucial daily activities2. For example, CVL can restrict employment opportunities due to the inability to read3, impact the perception of non-verbal social information4, change normal driving habits 5, and increase the rate of motor vehicle collisions6. In addition to these objective challenges, studies have shown that patients with CVL experience a significantly decreased quality of life. Comprehensive studies using questionnaires like the Short-Form Health Survey, EuroQoL EQ-5D, Sickness Impact Profile, National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire, Impact of Vision Impairment, and others, have highlighted patients' difficulties in mental health issues, such as sadness, anxiety, and fear7. It is emphasized that low vision rehabilitation should ultimately aim to improve the quality of life8,9. Unfortunately, managing CVL-related diseases remains exceptionally challenging. For instance, the primary therapy for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) involves costly intraocular injections of anti-neovascular drugs and requires long-term follow-up10. Despite this, many patients are unable to preserve their residual vision and become blind11. Thus, there is a growing interest in finding effective approaches to address low vision and improve vision-related quality of life.

Patients with CVL tend to naturally develop compensatory oculomotor strategies to adapt to their lost visual field, such as using preferred retinal loci in healthy eccentric retinal areas for fixation12. However, even with training sessions like oculomotor training and perceptual training, the benefits are limited12,13,14. Consequently, a wide range of low vision aiding (LVA) devices have been developed to leverage residual vision through optical, non-optical, or digital principles to enhance visual function 8,15. These technologies are available in various formats, including desk-mounted, handheld, and head-mounted devices (HMDs) 9. The relatively newer HMD technology has shown advantages over the former two formats in terms of convenience and versatility while delivering favorable aiding effects 9. Technological advancements have driven modern HMDs to be even more comfortable to wear and to offer a broader range of functions, indicating their potentials in clinical applications 16,17.

However, because CVL and peripheral visual field loss (PVL) often have distinct pathologies and impact different aspects of patients' daily lives 18, specific working principles for vision improvement are necessary to achieve the best therapeutic effect. For example, a HMD called Crystal (OXSIGHT Limited, UK) was designed to aid PVL by utilizing a prism system to shrink images, fitting them onto the central functional area of the retina and thus expanding the user's field of view. Similarly, the company introduced another HMD named Onyx (OXSIGHT Limited, UK) in eyewear form, specifically tailored for CVL19,20. It features a camera system that projects magnified live video streams on two organic light emitting diode (OLED) display screens in front of the eyes, allowing patients to engage the remaining peripheral vision to maintain balance and spatial awareness. It also incorporates artificial intelligence (AI) and autofocusing lenses to detect text, faces, and objects, adjusting the shade for lower light sensitivity based on ambient light conditions21. This might be especially important for CVL patients since the functional peripheral retina is more sensitive to light levels than the central area. Devices employing these principles to enhance vision might be promising for low vision rehabilitation and warrant further evaluation.

In the current study, we assessed the clinical effectiveness of the HMD Onyx on visual function and vision-related life quality in low vision patients with CVL. We also explored potential factors that might influence the benefits of this device.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

In this single-center, prospective cohort study, we recruited patients with persistent binocular central visual field loss due to all kinds of ocular diseases who met our inclusion criteria. Participants with complete medical histories and ocular examinations, including the static perimetry (Octopus 900® EyeSuite Perimetry, Haag-Streit, Switzerland), color fundus photography (CFP), optical coherence tomography (OCT), fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), and indocyanine green angiography (OCTA), were reviewed from the Department of Ophthalmology at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) during the period from July 1, 2021, to July 31, 2024.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA, assessed with the Snellen chart) in the better eye was between hand movement (HM) and 0.15; (2) Binocular central visual loss (CVL), defined by defects within the central 30-degree visual field in the static perimetry assessment. The defect should include at least a cluster of four points where p < 5% with at least two of these points having p < 1% on the “corrected probabilities” plot. This ensures that the defect corresponds to a visual angle of at least 6°–12°22,23; (3) The status of CVL, low vision, and disease lesions remained stable for at least six months prior to enrollment. The status of disease lesions was comprehensively assessed by clinical examination and associated ocular imaging, like OCT, OCTA, and FFA, etc.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Preservation of the central 5-degree visual field in the static perimetry assessment; (2) Treatable low vision conditions, including uncorrected myopia, unhealed corneal ulcer, severe cataracts, and active fundus diseases, such as unscared neovascularization and unresolved macular edema or hemorrhage; (3) Diseases characterized by peripheral or widespread visual field defects, including extensive corneal opacity, advanced glaucoma, vitreous hemorrhage, uveitis, retinitis pigmentosa, central retinal artery/vein occlusion and retinal detachment; (4) Any treatments within three months prior to enrollment, including anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapies, retinal laser photocoagulation, pars plana vitrectomy, and the use of other low vision aids (LVAs); (5) Presence of any physical or mental conditions that could hinder the proper use of head-mounted displays (HMDs), such as physical disabilities, hearing disorders, and cognitive or psychiatric impairments.

Patient information, including age, sex, cause of CVL, and treatment history, was subsequently recorded. We also extracted the mean deviation (MD) values from static perimetry reports. Since diseases causing global visual field defects were excluded, the MD values could properly reflect the severity of CVL, which we classified into two categories: moderate (MD > −8.0 dB) and severe (MD ≤ −8.0 dB) 24.

The study followed the principles outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki 25 and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China (project number K4473). Informed consent was obtained from all participants following a thorough explanation of the study's objective and methodology.

Materials

Onyx is designed in a box shape with a subtle curvature to accommodate the contours of the face. When positioned on the table, the device measures 71 mm in height and 66 mm in thickness. The removable arms of the device serve to enhance its versatility. Two areas containing operational buttons are placed on the top surface (Fig. 1A). The device integrates a front camera that captures images, relaying them to an AI calculation unit designed for text, face, and object recognition (Fig. 1B). The processed images are projected via two adjustable lenses, directing them towards the user's peripheral retina (Fig. 1A). The user can zoom the live image to 6 levels (−1, 0 (default), 1, 2, 3, 4). A Refocus button is available if the image is out of focus.

Appearance and main parts of OXSIGHT Onyx. The main part of Onyx presented in a box shape with mild curvature facing the user. (A) The camera in middle front is marked with a pink triangle. (B) Two control panels on the top are marked with blue stars. Two adjustable lenses facing the user are marked with green circles.

Procedure

At baseline, the near and distance visual acuity (VA) of participants were recorded using the Radner Reading Chart at 30 cm and the Snellen chart at 1 m, respectively. Face and object recognition abilities were assessed using three distinct human faces and three distinct objects (a clock, ship, and house), each independently printed on a figure card. Participants were instructed to recognize and report what they could perceive from the figure cards at a distance of 30 cm. A five-point scale was employed to assess their recognition ability: (1 point) unable to detect faces or objects; (2 points) able to see figures and their primary colors; (3 points) able to determine whether the figures are faces or objects based on their shapes and outlines; (4 points) able to identify facial expressions or main structures of the objects; (5 points) able to tell specific details of the faces or objects, such as their shadows and internal lines. Scores assigned to each figure card were summed up to obtain the total scores for face and object recognition, respectively. The mean value of the two total scores was defined as the combined recognition score. Additionally, participants were guided to report their main vision-related difficulties encountered in life and to complete the Low Vision Quality-of-Life questionnaire (LVQOL), which served as a reflection of their subjective assessments of visual-related quality of life26.

Before formal usage, participants received comprehensive training and a final check on the proper operation of the device. They were then guided to use the Onyx for 4 to 6 h daily over a month. The device logged the usage time. Participants who failed to reach the daily usage target were encouraged to compensate during subsequent periods to meet the total goal. To ensure smooth operation of the device, both remote and on-site technical support were readily accessible. After a month of consistent usage, all participants revisited the Department of Ophthalmology at PUMCH to repeat the assessments conducted at the start. Participants with an average usage time of less than 4 h per day were deemed ineligible for subsequent analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD and categorical data were presented as number (percentage). The distance VA measured using the Snellen chart was converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical analysis. Paired t-tests were used to compare the baseline and final assessments for visual functions and the LVQOL scores. A significant improvement in near VA was defined as an increase of ≥ 0.1 LogRAD, and for distance VA, an increase of ≥ 0.1 LogMAR. A significant improvement in the combined recognition score was defined as an increase of ≥ 3 points, and for the total LVQOL score, an improvement of ≥ 7 points. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to identify potential factors influencing the enhancement of recognition score and the LVQOL score, respectively. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The study initially enrolled 56 patients, but 15 of them were excluded due to inadequate usage time. Thus, the final analysis includes 41 participants, of which 20 were males (48.78%). The average age was 69.1 ± 12.8 years. Most participants fit into the 50 to 89-year age group (n = 36, 87.80%, Table 1). Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) was the primary cause of CVL (n = 20, 48.78%), followed by polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (n = 7, 17.07%), central exudative chorioretinopathy (n = 4, 9.76%), central serous chorioretinopathy (n = 3, 7.32%), pathologic myopia (n = 2, 4.88%), choroidal osteoma (n = 2, 4.88%), corneal opacity (n = 2, 4.88%), and autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (n = 1, 2.44%), , central exudative chorioretinopathy (n = 1, 5.56%). Patients with moderate CVL had a mean MD of -6.78 ± 0.60 dB (n = 21, 51.22%), while those with severe CVL had a mean MD of -9.02 ± 0.73 dB (n = 20, 48.78%). The most frequently reported difficulty in life was reading, followed by recognizing faces/objects, watching TV, and walking, etc. All participants received positive treatments prior to the study, such as topical antibiotic eye drops, intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF drugs, pars plana vitrectomy, and retinal laser coagulation. Of note, one patient with autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy received intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy because of secondary choroidal neovascularization. None of the participants reported any substantial discomfort during period of formal usage.

Comparison of visual functions and the LVQOL scores before and after wearing Onyx

As shown in Table 2, after a month of usage, 25 participants (60.98%) showed significant improvements in near VA, with the average near VA significantly improving from 1.10 ± 0.13 LogRAD to 0.99 ± 0.14 LogRAD (P < 0.001). Significant improvement in distance VA was reported by 33 participants (80.49%), with the average value improving from 1.58 ± 0.27 LogMAR to 1.36 ± 0.29 LogMAR (P < 0.001). 37 participants (90.24%) showed significant enhancements in the combined recognition score, with the average value increasing from 7.32 ± 2.53 points to 12.68 ± 1.63 points (P < 0.001).

Scores of the LVQOL questionnaire exhibited significant improvements in 28 patients (68.29%), with the average value increasing from 52.05 ± 3.75 points to 60.95 ± 3.80 points (P < 0.001). Among the four subsections of the questionnaire evaluating different aspects of life, “Reading and Fine Work” showed the highest percentage of improvement (22.07%), followed by “Activities of Daily Living” (16.63%), “Adjustment” (15.67%) and “Distance Vision, Mobility and Lighting” (12.01%).

Linear regression analyses for factors correlating with the improvement in the combined recognition score and the LVQOL score

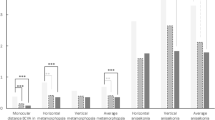

Potential factors influencing the enhancements in visual functions and vision-related quality of life were explored using univariate linear regression analysis. Independent variables with a P value < 0.15 were subsequently validated in a multivariate linear regression model. As shown in Table 3, the outcome of multivariate linear regression demonstrated a negative correlation between the improvement in combined recognition ability and baseline recognition score (β = −0.634, 95% CI: −0.838 to −0.430, P < 0.001). Improvement in the LVQOL score showed a negative correlation with both age (β = −0.094, 95% CI: −0.186 to −0.001, P = 0.047) and baseline LVQOL score (β = −0.615, 95% CI: −0.944 to −0.287, P = 0.001). Figure 2 illustrated the scatter distribution of four continuous variables, along with their relationships to the improvements in the combined recognition ability (green lines) and the LVQOL score (orange lines).

The scatter distribution of potential factors and their corresponding relationships to the improvements in combined recognition score and the LVQOL score. A red asterisk on the top right corner of each graph indicates a significant correlation with corresponding dependent variables in the multivariate linear regression analysis. VA visual acuity, LVQOL low vision quality of life.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the clinical performance of an innovative HMD that projects captured images to the functional peripheral regions of the retina and utilizes AI technologies to enhance visual quality for patients with CVL. The 41 participants had various ocular conditions, with age-related macular degeneration being most prevalent (n = 20, 48.78%). After wearing the HMD consecutively for a month, we observed significant improvements in visual acuity, face and object recognition abilities, and positive changes in subjective appraisals regarding vision-related life quality.

As previously mentioned, CVL is the major form of low vision that primarily affects indoor daily activities. Evidence suggests that reading is one of the primary reasons patients seek low vision rehabilitation services 27,28. However, challenges in outdoor activities and navigation in unfamiliar environments can also occur in CVL when the affected visual field is extensive. Therefore, both near and distance VA were assessed in our study. 25 participants (60.98%) experienced at least one line of near VA enhancement, and 33 participants (80.49%) experienced at least one line of distance VA enhancement. Fisher’s exact test (results not presented) showed a similar distribution of these improvements across the two grades of CVL, indicating that the severity of CVL did not influence the improvement of near and distance VA. The higher rate of distance VA improvement might be explained by other clinical characteristics of CVL, needing further exploration. Another frequently used index is reading speed. It was not assessed in our study because most participants were elderly Chinese and there is currently no Chinese version of the Radner Reading Chart. Some studies have reported a negative impact of HMDs on reading speed due to reduced visual span and image movement 9,29. However, a recent systemic review indicated that HMDs and stand-mounted devices showed no significant difference in reading speed assessment 30. Moreover, advancements in text recognition technologies could mitigate the visual impairment by enabling fast text recognition and reading aloud 31. Thus, reduced reading speed might not be a significant barrier to the use of HMDs.

Recognition ability for faces and objects is another critical concern for low vision patients with CVL 28. Unlike VA, this indicator better represents general visual function as it involves the recognition of outlines, colors, and contrast, similar to real-life situations. Our test included common examples of faces and objects, with different scores assigned to represent various levels of recognition abilities. 37 participants (90.24%) demonstrated considerable improvements in recognition abilities, which were more prevalent than those observed in VA assessments. Additionally, we found that the improvement of recognition ability had a negative linear correlation with baseline recognition score. This finding suggests that the functional peripheral retina might be crucial for patients with severe CVL. The worse the CVL, the more significant the improvements in visual function once the functional peripheral retina is utilized.

Fraser et al. reported that beyond reading simple information, difficulties in more complex activities such as reading signs, seeing steps, stairs, or curbs, and reading large print prompt patients to seek low vision services 32. Indeed, the nature of visual impairment is intricate, and routine clinical vision assessments, such as VA, contrast sensitivity, and visual field tests, may not fully capture the impact of low vision on daily life. Therefore, various questionnaires have been widely used to assess vision-related life quality, such as the NEI VFQ, LVQOL, VA LV VFQ-48, and IVI questionnaire 33. Our study chose the 25-item LVQOL questionnaire because it is highly internally consistent, reliable, simple to use, and has been implemented in other studies to assess LVAs 9,26. During the initial development and validation of this questionnaire, the internal test showed 334 low vision patients had an improvement of about 6.8 points 26. To provide a proximate comparison, our study defined the significant improvement in the LVQOL score as ≥ 7 points 9. Our results showed the average score significantly increased from 52.05 ± 3.75 points to 60.95 ± 3.80 points (P < 0.001) and 28 patients (68.29%) achieved the defined significant improvements. These improvements indicated the efficacy of Onyx might be comparable with other LVAs, but further investigations are required for a reliable comparison.

The subsections of the LVQOL score further supported the main benefits of Onyx, as the scores for “Reading and Fine Work” and “Activities of Daily Living” showed the highest improvements (22.07% and 16.63%, respectively). Interestingly, despite these improvements mainly relying on near-distance visual functions, the improvement in near VA seemed to be lower than that of distance VA (13.92% versus 10.00%). Two possible reasons might explain the phenomenon. (1) Patients with CVL often perform better in outdoor activities than indoor activities. Thus, despite substantial enhancements in distance VA, they may be more sensitive to the improvements in near VA. (2) As visual function assessment is more complex than mere VA, there might be other factors such as light conditions, object color, and motion that influence subjective appraisals of vision-related life quality. However, these inferences require further exploration.

Our study revealed that the enhancement of the LVQOL score exhibited a negative linear correlation with age (multivariate β = −0.094, 95% CI: −0.186 to −0.001, P = 0.047). In a recent study assessing the performance of a smartphone-based LVA, the LVQOL score for patients under 40 years old improved from 69.33 ± 9.55 points to 78.08 ± 9.88 points (P = 0.024), while the change in those older than 40 years was not significant different (from 60.09 ± 17.35 points to 59.86 ± 16.37, P = 0.653)9. Other studies also indicate younger patients typically showed more optimistic assessments of LVAs34. Our study supports this finding with a more robust quantified relationship. However, as conclusions concerning the factors influencing the use of LVAs vary widely35, more comprehensive studies are needed to identify these major factors.

Additionally, though various questionnaires are available, they may lose specificity when applied to different types of visual field loss, as most were developed based on a general definition of low vision. For instance, over 20% of low vision patients included in verifying the LVQOL questionnaire are under 50 years old , with some even below 20 years old26. However, the daily life characteristics of different age groups should be carefully considered. Questionnaires like the Cardiff Visual Ability Questionnaire for Children (CVAQC), which focuses on school activities, have already been developed for children with visual impairments 36,37. It might be reasonable to advocate for the development of questionnaires specifically devised to assess life quality for elderly individuals with CVL.

Based on our analysis of Onyx’s performance, we concluded that younger patients with more severe CVL who care more about indoor activities might benefit most from this device. However, the indices used to assess the recognition ability for objects and faces seemed over-optimistic, as the high percentage of improvements did not effectively translate to the LVQOL score improvements. Future studies are warranted to seek more appropriate indices to evaluate the performance of Onyx. The device could be further improved with advances in VA enhancement (currently only about 10% for near distance VA), reduced device weight, and better AI technologies.

The study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was limited. Studies on LVAs often have limited sample sizes, possibly due to the prevailing notion that regaining lost sight is challenging and the insufficient promotion of low vision services. Encouraging public understanding of low vision rehabilitation could facilitate larger-scale studies in the future. Secondly, although the formal usage duration in our study was similar to other studies 9, it has been reported that prolonged low vision can lead patients to adapt to their conditions 32. Thus, extended usage duration might also enhance patients' reliance on LVAs, which warrants further explorations. Thirdly, our study recorded various ocular conditions, with AMD being the most common, while the numbers of other conditions were limited. This hindered us from further studying the potential impact of disease heterogeneity on the efficacy of Onyx. Though we designed strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to only recruit patients with CVL, the results might still be more meaningful for patients with AMD than other diseases. Fourthly, when evaluating visual functions, we only used two-dimensional indicators, while humans live in a three-dimensional environment. Low vision patients may have severely impaired stereovision, and the assessment of it might also be necessary. Fortunately, new methods like augmented reality technology can facilitate three-dimensional visual function assessments, offering a more comprehensive evaluation of the benefits of LVAs 38,39.

Conclusions

Our study showed that the novel HMD Onyx was clinically effective in promoting visual function and vision-related life quality in low vision patients with CVL. Such patients might benefit from fully utilizing their functional periphery retina.

Data availability

After approval by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of PUMCH, the datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (YC) on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LVA:

-

Low vision aiding

- HMD:

-

Head-mounted device

- CVL:

-

Central vision loss

- VA:

-

Visual acuity

- LVQOL:

-

Low vision quality-of-life

- AMD:

-

Age-related macular degeneration

- PVL:

-

Peripheral visual field loss

- OLED:

-

Organic light emitting diode

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- BCVA:

-

Best corrected visual acuity

- HM:

-

Hand movement

- CFP:

-

Color fundus photography

- OCT:

-

Optical coherence tomography

- FFA:

-

Fundus fluorescein angiography

- OCTA:

-

Indocyanine green angiography

References

Klauke, S., Sondocie, C. & Fine, I. The impact of low vision on social function: The potential importance of lost visual social cues. J. Optom. 16(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2022.03.003 (2023).

Owsley, C. et al. Characteristics of low-vision rehabilitation services in the United States. Arch. Ophthalmol. 127(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.55 (2009).

Sivakumar, P. et al. Barriers in utilisation of low vision assistive products. Eye 34(2), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0545-5 (2020).

Sheldon, S. et al. The effect of central vision loss on perception of mutual gaze. Optom. Vis. Sci. 91(8), 1000–1011. https://doi.org/10.1097/opx.0000000000000314 (2014).

Sengupta, S. et al. Driving habits in older patients with central vision loss. Ophthalmology 121(3), 727–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.042 (2014).

Mckean-Cowdin, R. et al. Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 143(6), 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.022 (2007).

Evans, K. et al. The quality of life impact of peripheral versus central vision loss with a focus on glaucoma versus age-related macular degeneration. Clin. Ophthalmol. 3, 433–445. https://doi.org/10.2147/opth.s6024 (2009).

Van Nispen, R. M. et al. Low vision rehabilitation for better quality of life in visually impaired adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1(1), CD006543. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006543.pub2 (2020).

Yeo, J. H. et al. Clinical performance of a smartphone-based low vision aid. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 10752. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14489-z (2022).

Ammar, M. J. et al. Age-related macular degeneration therapy: A review. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 31(3), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1097/icu.0000000000000657 (2020).

Ricci, F. et al. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Therapeutic management and new-upcoming approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218242 (2020).

Tarita-Nistor, L. et al. Plasticity of fixation in patients with central vision loss. Vis. Neurosci. 26(5–6), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952523809990265 (2009).

Chung, S. T. L. Improving reading speed for people with central vision loss through perceptual learning. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52(2), 1164–1170. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-6034 (2011).

Maniglia, M., Visscher, K. M. & Seitz, A. R. Perspective on vision science-informed interventions for central vision loss. Front. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.734970 (2021).

Peláez-Coca, M. D. et al. A versatile optoelectronic aid for low vision patients. Ophthalm. Physiol. Opt. 29(5), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2009.00673.x (2009).

Wittich, W. et al. The effect of a head-mounted low vision device on visual function. Optom. Vis. Sci. 95(9), 774–784. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0000000000001262 (2018).

Deemer, A. D. et al. Low vision enhancement with head-mounted video display systems: Are we there yet?. Optom. Vis. Sci. 95(9), 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1097/opx.0000000000001278 (2018).

Ehrlich, J. R. et al. Head-mounted display technology for low-vision rehabilitation and vision enhancement. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 176, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2016.12.021 (2017).

Senjam, S.S., Gupta, V., Vashist, P. et al. Assistive Devices for Children with Glaucoma. Childhood Glaucoma: A Case Based Color and Video Atlas. 403–421 (Springer, 2023).

Harvey, B. Developments in electronic low vision aids: Adaptive technology 5. Optic. Sel. 2021(7), 8634–8641 (2021).

Senjam, S.S., Aggarwal, S., Beniwal, A. et al. Head-mounted display (HMD) assistive technology for low vision and vision rehabilitation.

Bronstad, P. M. et al. Driving with central field loss I: Effect of central scotomas on responses to hazards. JAMA Ophthalmol. 131(3), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.1443 (2013).

Addleman, D. A., Legge, G. E. & Jiang, Y. V. Simulated central vision loss impairs implicit location probability learning. Cortex 138, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2021.02.009 (2021).

Acton, J. H., Gibson, J. M. & Cubbidge, R. P. Quantification of visual field loss in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One 7(6), e39944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039944 (2012).

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Wolffsohn, J. S. & Cochrane, A. L. Design of the low vision quality-of-life questionnaire (LVQOL) and measuring the outcome of low-vision rehabilitation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 130(6), 793–802 (2000).

Miller, A. et al. Are wearable electronic vision enhancement systems (wEVES) beneficial for people with age-related macular degeneration? A scoping review. Ophthalm. Physiol. Opt. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.13117 (2023).

Amore, F. et al. Efficacy and patients’ satisfaction with the ORCAM MyEye device among visually impaired people: A multicenter study. J. Med. Syst. 47(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-023-01908-5 (2023).

Crossland, M. D. et al. Benefit of an electronic head-mounted low vision aid. Ophthalm. Physiol. Opt. 39(6), 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12646 (2019).

Virgili, G. et al. Reading aids for adults with low vision. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4(4), CD003303. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003303.pub4 (2018).

Moisseiev, E. & Mannis, M. J. Evaluation of a portable artificial vision device among patients with low vision. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134(7), 748–752. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1000 (2016).

Fraser, S. A. et al. Critical success factors in awareness of and choice towards low vision rehabilitation. Ophthalm. Physiol. Opt. 35(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12169 (2015).

Vélez, C. M. et al. Psychometric properties of scales for assessing the vision-related quality of life of people with low vision: A systematic review. Ophthalm. Epidemiol. 30(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2022.2093919 (2023).

Watson, G. R. et al. Veterans’ use of low vision devices for reading. Optom. Vis. Sci. 74(5), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006324-199705000-00020 (1997).

Lorenzini, M. C. & Wittich, W. Factors related to the use of magnifying low vision aids: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 42(24), 3525–3537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1593519 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Validation of an instrument to assess visual ability in children with visual impairment in China. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101(4), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308866 (2017).

Özen Tunay, Z. et al. Validation and reliability of the Cardiff Visual Ability Questionnaire for children using Rasch analysis in a Turkish population. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 100(4), 520–524. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307122 (2016).

Gopalakrishnan, S. et al. Comparison of visual parameters between normal individuals and people with low vision in a virtual environment. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23(3), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0235 (2020).

Angelopoulos, A. N. et al. Enhanced depth navigation through augmented reality depth mapping in patients with low vision. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 11230. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47397-w (2019).

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China. Grant numbers: 82271112.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G. contributed to the concept of the study. X.G., Y.W., and X.Z. designed the study and did the literature search. X.G., Q.Z., Y.W., and X.Z. collected the data. X.G., Q.Z., and X.Z. did the data analysis and data interpretation. X.G. drafted the manuscript. X.Z. and Y.C. critically revised the manuscript. Y.C. provided research funding, coordinated the research, and oversaw the project. All authors had access to all the raw datasets and the corresponding author (Y.C.) has verified the data and had final decision to submit for publication. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the principles outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), China (project number K4473). Informed consent was obtained from all participants after a detailed explanation of the study's purpose and design.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, Q. et al. Clinical efficacy of a head-mounted device for central vision loss. Sci Rep 14, 21384 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72331-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72331-0